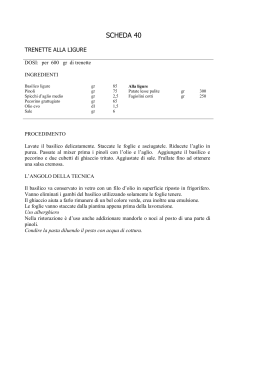

30 blue cover Foglie di basilico di Prà, primo e fondamentale ingrediente per pestellare un buon pesto Leaves of Prà basil, the first and fundamental ingredient to make a good pesto with a mortar and pestle Verde cover blue 31 come lo smeraldo Green as an Emerald Misteriose le origini del pesto, la salsa ligure nota nel mondo. Gli studiosi ne hanno cercato traccia in libri, ricettari e atti notarili ma la ricetta compare per la prima volta nell’800 come condimento Pesto, Liguria’s famous sauce, has mysterious origins. Scholars have searched for traces in books, recipe books, and notarial deeds, but the recipe appears for the first time only in the 1800s as a condiment e c’è un piatto che identifica la cucina genovese, questo è sicuramente il pesto, morbida e profumatissima salsa, verde come lo smeraldo, che impreziosisce la pasta conferendole un sapore unico. Per questa ragione ai cultori della gastronomia e agli storici dell’alimentazione sarebbe piaciuto scoprire negli annali antichi un documento o almeno un cenno alla preziosa salsa, che ne potesse stabilire un’origine lontana nel tempo, come è accaduto, ad esempio, per la farinata (che affonda le sue radici nel Medio Evo) o come nel caso della torta pasqualina che discende direttamente dalla “gattafura” del XVI secolo. Appassionati e studiosi hanno consultato minuziosamente i testi di cucina dei secoli scorsi, hanno passato in rassegna i ricettari e i libri dei conti delle famiglie aristocratiche della città, hanno consultato gli atti dei notai che fin dal XIII secolo annotavano ogni particolare relativo alla vita quotidiana, atti tuttora conservati nell’Archivio di Stato di Genova. Del pesto, però, fino al 1800, nessuna traccia. Scrive Paolo Lingua, giornalista, autore di saggi storici, nonché delegato dall’Accademia Italiana della Cucina (Genova Est), nel libro La C ucina dei Genov esi: “Troviamo la S f there is any speciality that defines Ligurian cooking, then surely it is Pesto – soft sauce, green as an emerald. It embellishes any pasta and gives it a unique flavor. For this reason, gastronomical experts and nutritional historians wanted to look for a hint in the readings of ancient documents, of when this cherished sauce was first concocted, just like the Farinata (whose origins go all the way back to the medieval times) or the Pascualina pie that descends directly from the “gattafura” of the 16th century. Scholars and enthusiasts have meticulously consulted cookbooks of past centuries. They combed through recipe books, books, accounting documents of aristocratic families, and even notarial deeds which took note of every particular aspect of everyday life since the 13th century, and which are still preserved in the archives of Genoa, but found no trace of pesto until the 1800s. Paolo Lingua, journalist, author of historical essays and delegate to the Academy of Italian Cooking (Genoa East), writes in the book La C ucina Dei Genov esi (Genoese Cooking): “In Genoa, pasta seasoned with pesto can be traced back to the 1820s and I Egle Pagano 32 blue cover cover blue Prima del 1800, sembra che il pesto non fosse ancora stato ideato. La prima pasta e i primi minestroni conditi con questa salsa accertati, invece, risalgono alla Genova degli anni Venti e Trenta del XIX secolo Before 1800, it seems that pesto had not yet been invented. The first attested pasta (and minestrone) dressed with this sauce dates back to Genoa in the 1820s and 1830s pasta condita con il pesto nella Genova degli anni Venti e Trenta del XIX secolo: il suo successo è fulmineo e dilagante. Viene da chiedersi se il pesto sia davvero ‘un fulmine a ciel sereno’ oppure abbia precise radici. Ma credo, senz’ombra di smentite, che all’origine del pesto ci sia la salsa di noci o comunque tutte le salse a base di semi oleosi apprese in Oriente sin dal Medio Evo. Queste salse, sovente unite a quagliate (la prescinseua, tuttora usata nel Genovesato, discende dallo yogurt, diffuso nelle zone del Mar Nero, dove gli antichi Genovesi avevano i loro terminal commerciali), si usavano per guarnire torte salate o condire paste secche e lasagne. E’ ignoto chi abbia aggiunto alla salsa di pinoli o noci (e formaggio) il basilico (l’olio forse, in alcu- 30s; its success was instantaneous and rampant. One wonders if pesto was just a bolt from the blue or if it has precise roots. I believe without reasonable doubt, that the origin of pesto can be traced to the walnut sauce or any other sauce that is based on oilseed brought in from the Orient during the medieval times. These sauces frequently combined with cheese (the prescinseua cheese which is still used in the “Genovesato” comes from yogurt, diffused in the Black Sea area where the Genoese had their commercial terminal), were used to garnish pot pies or season dried noodles and lasagne. No one knows for sure who added basil to the cheese and pine nut-walnut sauce (the oil was probably present to help dissolve the Un libretto al prof umo di basilico Basilico dappertutto. Anche fra le pagine del divertente Profumi e sapori, il libretto pubblicato dalla casa editrice AbaLibri e ripresa dall’Assessorato al Turismo della Regione Liguria. In 24 pagine ecco il basilico genovese, quello doc di Prà, dal quale nasce per magia il pesto. Salsa realizzata in molte varianti, con noci o pinoli, con pecorino o parmigiano o prescinseua, ma sempre con olio d’oliva ligure extravergine e aglio. Tutti ingredienti indispensabili. Come i consigli per preparare il pesto. Assolutamente da seguire. Gran finale nell’ultima pagina dove è allegata una bustina di semi, sufficiente a far crescere un metro quadrato di basilico in casa, sul balcone e sul terrazzo, o nel proprio orto. Con istruzioni per l'uso, ovviamente. In tre lingue: italiano, inglese e tedesco. Un modo per fare tutto da se: dal basilico al pesto da gustare con un fumante piatto di trofie, lasagne, pansoti, trenette o ravioli. Il libretto Profumi e sapori (5 euro) si compra nelle migliori librerie o sul sito www.abalibri.it. ni casi, era già presente, probabilmente per stemperare l’acidulo della quagliata o del pecorino-ricotta fresco): fatto sta che la nuova salsa, di colore verde pallido, ottenne un successo immediato”. Giovanni Rebora, storico dell’alimentazione e docente all’Università di Genova, recentemente scomparso, era convinto che il pesto fosse una creazione databile intorno alla metà dell’Ottocento, evoluzione di una salsa agliata, a base appunto di aglio e basilico, successivamente arricchita con il formaggio: in un primo momento un misto di parmigiano e “olandese”, formaggio dalla “crosta” rossa importato dai Paesi Bassi, poi sostituito, a Genova dal pecorino sardo, nel Tigullio e nel Levante dalla prescinseua. La successiva aggiunta di pinoli (noci nel Levante) risalirebbe agli ultimi due decenni dell’800. Sostanzialmente d’accordo sulla nascita del pesto anche Silvio Torre, che nel Gra nde Li b ro d el l a Cuci na l i gu re, sottolinea il ruolo dell’ingrediente olio, ricordando come questo elemento non fosse presente nelle salse agliate di epoca medievale e rinascimentale. La coltivazione dell’ulivo, slightly sour curd or the fresh pecorino or ricotta), but the fact remains that the new, pale green sauce was an immediate success”. Giovanni Rebora, nutritional historian and a professor at the University of Genoa who recently passed away, was convinced that pesto could be traced back to the middle of the 1800s. According to Rebora, pesto could have evolved from a garlic sauce, the basic ingredients of which were precisely basil and garlic, and then embellished with cheese. At the start, a mixture of parmesan and a Dutch cheese with red crust imported from the Netherlands was used. But in Genoa, it was replaced by Sardinian pecorino, and in Tigullio and Levante, by prescinseua cheese. Pine nuts (walnuts in Levante) were added towards the last half of the 1800s. Silvio Torre basically agrees with this version of the origin of pesto, but emphasizes in the G ra n d e L i b ro d e l l a Cu c i n a L i g u re (The Complete book of Ligurian Cooking), the importance of the role played by the oil, noting that this A booklet with the scent of bas il Basil everywhere. Even among the pages of the square-shaped entertaining booklet Profumi e sapori, published by the authentically Ligurian publishing house, AbaLibri, and Regione Liguria. Its 24 pages present Genoese basil, Prà basilico doc, from which pesto is magically created, the sauce at the base of some of the more traditional recipes from Superba and the surrounding area. Photos of strictly marble mortars and just as strictly wooden pestles to make this sauce in many varieties: with walnuts or pine nuts, with pecorino, parmesan or prescinseua. But always with extravirgin Ligurian olive oil and garlic. All essential ingredients. Like the advice on how to prepare the pesto. Not to be missed. The grand finale is found on the last page with a bag of seeds attached, enough to grow a square metre of basil in your home, on the balcony or terrace, or in the garden. With instructions for use of course. In three languages: Italian, English and German. A decisively Obama-style publication, very trendy, with green charm. A way to do everything by yourself: from basil to pesto to be enjoyed with a piping hot dish of trofie, lasagne, pansoti, trenette or ravioli. The booklet Profumi e sapori (5 euro) can be bought in the best bookstores or on the website www.abalibri.it. Secondo il Grande Libro della Cucina ligure di Silvio Torre, la diffusione del pesto si deve all'affermarsi dell'impiego dell’olio d’oliva in cucina, fra la fine del ’700 e l’inizio dell’800, quando "i genovesi" iniziarono "a spendere il loro denaro nel disboscare montagne per piantarvi degli ulivi" According to Silvio Torre's Grande Libro della Cucina ligure, the spread of pesto is owed to the manifestation of the use of olive oil in cooking, between the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century, when the Genoese started "to spend their money in deforesting the mountains to plant olives" 33 blue cover 34 Pe r s a p e r n e d i p i ù Da consultare la pubblicazione Costa e Entroterra, cofanetto multikit pubblicato dalla Provincia di Genova. Dove si legge che l’area del Parco del Basilico, che va dalla costa alle colline terrazzate dell’interno, interessa la zona di Prà più idonea alla coltura del basilico, basandosi anche sulla documentazione catastale di fine Settecento. E che “il basilico è condito con l’aria di mare”: per questo nei velieri esiste ancora una zona chiamata il giardinetto, in quanto era riservata dai marinai genovesi alle piantine di basilico necessarie per preparare il pesto, a cui non potevano rinunciare neppure durante la navigazione. To f i n d o u t m o re Not to be missed is the publication Provincia di Genova, Costa e Entroterra. Four booklets in a multi-kit boxset published by the Genoa Provincial Tourist Board. Inside we read that the area of Parco del Basilico which stretches from the coast to the inland terraced hills, includes the zone of Prà as the most suitable for basil cultivation, based on the land registry documentation from the end of the 18th century. Essential for preparing the inimitable Genoese pesto, the basil is seasoned with sea air. It is no coincidence that yachts also have an area called the little garden, where Genoese sailors kept basil plants to make pesto, which they couldn’t do without even while sailing. P.Tr. Info www.provincia.genova.it www.parco-basilico.it cover blue del resto, pur iniziata nel ‘500 raggiunse il massimo sviluppo solo nella seconda metà del ‘700, al punto che Montesquieu nella lettera da Genova datata 1782 annotava: “Dacché i genovesi hanno perduto un po’ dei loro capitali a Vienna e a Venezia, in Spagna e in Francia e hanno preso a spendere il loro denaro nel disboscare montagne per piantarvi degli ulivi, da vent’anni a questa parte tali colture sono molto aumentate”. E’ dunque fra la fine del ’700 e l’inizio dell’’800 che comincia ad affermarsi l’impiego dell’olio d’oliva in cucina ed è molto probabile che ciò abbia favorito la nascita e l’affermazione del pesto. La prima codificazione della ricetta, comunque, si trova nella C u c i n i e r a G e n o v e s e di G.B. e Giovanni Ratto del 1863, nel capitolo Sughi, intinti e soffritti alla voce Battuto alla genovese (Pesto): ”Prendete uno spicchio d’aglio, basilico, formaggio sardo ( nella prima edizione: formaggio olandese , n.d.r.) e parmigiano grattugiati e mescolati insieme, e dei pignoli. Pestate il tutto in un mortaio con poco burro finché sia ridotto in pasta. Scioglietelo dunque con olio fino in abbondanza. Con questo battuto si condiscono le lasagne, i tagliatelli, i (sic) gnocchi ( troffie ), unendovi un po’ d’acqua calda senza sale per renderlo più liquido”. Nell’Ottocento la pasta al pesto era peraltro considerata un cibo popolare. Vi si aggiungevano patate, fave o fagiolini, a volte anche zucchine tagliate a tocchetti che venivano cotti insieme alla pasta. L’aggiunta di verdure stagionali è una prassi ancora valida nel Levante, dove spesso fra gli ingredienti figura ancora la prescinseua , consigliabile soprattutto se il pesto condisce gnocchi o troffie con farina di castagne. A Genova sopravvive solo l’uso di patate e fagiolini, in aggiunta alle trenette (linguine) classiche o avvantaggiate (fatte con farina integrale), o alle troffiette (gnocchetti di fa- ingredient was not present in the sauces and garlic sauces of the medieval and renaissance periods. Although olives were cultivated in Liguria as early as the 1500s, its cultivation reached its height around the 1700s, so much so that Montesquieu, in a letter written from Genoa in 1782, notes that “Inasmuch as the Genoese have lost a little of their capital to Vienna, Venice, Spain and France, they have spent their money for the deforestation of their mountains to plant their olive orchards which in 20 years have increased in number”. So it was by the end of the 1700s and beginning of the 1800s that the use of olive oil began to take hold in the kitchens of Liguria. This probably contributed to the birth and popularity of pesto. The first codification of the recipe is found in C u ci n i e ra G en o v es e by G.B. and Giovanni Ratto, 1863, in the chapter Sughi, intinti e soffritti (Sauces, dips and fried ingredients), paragraph Battuto alla genovese (Pesto): “Take a clove of garlic, some basil, grated Sardinian cheese (in the first edition they ask for Dutch cheese) and parmesan mixed together, and pine nuts. Mix them all together and crush in a mortar with a pestle. Add a little butter and continue crushing until reduced into a thick paste. Generously pour some oil. This sauce can be used to season lasagne, flat noodles, and (sigh) gnocchi (troffie). You may want to dilute the sauce with some hot water (unsalted) to make it more liquid”. In the 1800s, pasta with pesto sauce was considered food for the masses. They added some potatoes, broad beans, green beans and sometimes cubed courgette, which were cooked together with the pasta. The addition of seasonal vegetables is still a common practice in Levante where prescinseua cheese is added, especially if the pesto sauce is used to season gnocchi or troffie made with chestnut flour. In Genoa, they add potatoes and green beans only if the pesto sauce is used to season the classic linguine (trenette) or the avvantaggiate (pasta made with rina di grano duro, lunghi mezzo dito mignolo, sottili e ritorti). La ricetta ottocentesca è quella tuttora praticata. La differenza sta soprattutto nello strumento usato per fare il pesto. Nella quotidianità il mortaio di marmo e il pestello di legno d’ulivo sono quasi sempre sostituiti ormai dal frullatore. Sono, inoltre, d’obbligo i pinoli fra gli ingredienti: ma solo se il pesto accompagna una pasta asciutta. Se lo si aggiunge, invece, al minestrone (come impone la ricetta classica: all’ultimo momento), il pesto deve essere fatto senza i pinoli. Paolo Lingua nel suo libro cita la motivazione che ne dava il marchese Giuseppe Gavotti, che fu per un quarto di secolo segretario dell’Accademia Italiana della Cucina: il pesto per il minestrone deve essere forte, maschio e “maleducato”. b wholemeal flour) or else the troffiette (thin, tiny and twisted gnocchi made with hard wheat, about 1.5 inches long). The recipe from the 1800s is still very much in use today. The only difference is in the tool used to make the pesto sauce. Nowadays the marble mortar and the olive wood pestle have been replaced by the food blender. The addition of pine nuts is important especially if the sauce is used to season pasta. If it is added to a minestrone (as the classic recipes dictate, the pesto is added only at the end) or thick vegetable soup, then no pine nuts should be included. In his book, Paolo Lingua states the reason given by the Marquis Giuseppe Gavotti who was Secretary of the Academy of Italian Cooking for a quarter of a century: pesto sauce for a minestrone should be strong, masculine and “boorish”. b La prima codificazione della ricetta del pesto si trova nella Cuciniera Genovese di G.B. e Giovanni Ratto, del 1863, nel capitolo Sughi, intinti e soffritti alla voce Battuto alla genovese The first codification of the recipe for pesto is found in Cuciniera Genovese by G.B. and Giovanni Ratto, 1863, in the chapter Sughi, intinti e soffritti under Battuto alla genovese 35

Scaricare