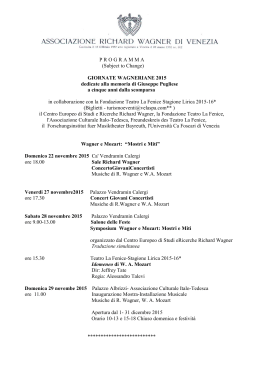

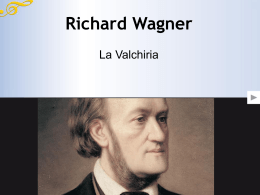

Editoriale « Di ogni civiltà ciò che resta per sempre sono l’arte, l’architettura, la letteratura, la musica». Lo scrive il compositore Claudio Ambrosini, il primo – in ordine alfabetico – a rispondere alla domanda che abbiamo rivolto a musicisti, critici, musicologi, registi, uomini di cultura e di spettacolo sul perché proprio la musica, molto più delle altre arti, soffra di indifferenza e disimpegno. I pareri arrivati dai teatri, i conservatori, le Università di tutta Italia sono una sinfonia di dolore ma anche di speranza, di indignazione e di orgoglio. Perché il male della nostra lirica, esploso in questi mesi con i tagli al Fondo Unico per lo Spettacolo, ha in realtà radici molto più lontane, più profonde e più tenaci. Come spiega il direttore del Conservatorio Benedetto Marcello, Giovanni Umberto Battel, «il generale disinteresse per la cultura musicale non è legato all’attuale situazione economica o sociale ma è l’amaro frutto di una mancanza di attenzione per tale settore nella scuola italiana.» Manca dunque un’educazione musicale, che è il punto di partenza, ma non solo. Le voci della nostra inchiesta raccontano di un pubblico carente, intimorito o ignorante, di una disattenzione dei mezzi di comunicazione, dell’elevato costo dei biglietti, di una scarsa capacità di ottimizzare le risorse, di poca circuitazione e, addirittura, dell’idea che la musica non sia più necessaria per la crescita intellettuale e civile della persona. In questo panorama i tagli imposti dalla Finanziaria portano la crudeltà del colpo di grazia che si abbatte senza complimenti, e proprio il fulgore della cultura di un tempo, come nota il direttore d’orchestra Federico Maria Sardelli, «fa apparire ancora più miserabile l’attuale condizione della musica in Italia». A Venezia, poi, con tre milioni di euro in meno per la prossima stagione, la Fenice potrà assicurare con assoluta certezza solo la programmazione del primo trimestre, mentre un paio di opere saranno inevitabilmente tagliate. L’anno nuovo si apre sotto il segno di Wagner e della Valchiria, rappresentata a Venezia l’ultima volta esattamente trent’anni fa. La Walchiria, diretta da Jeffrey Tate per la regia di Robert Carsen, sarà particolarmente intima perché, come spiega lo stesso Tate nel Focus dedicato all’opera, «la visione di Carsen si fonde bene con il mio modo di leggere questo lavoro, evidenziando l’aspetto lirico, i dettagli della partitura; in Wagner ci sono grandi momenti, quelli che tutti conoscono, ma a me piace che la direzione non abbia un carattere titanico e monumentale». A cornice della Walchiria ci sarà il V Concorso Internazionale per voci wagneriane, che tra il Malibran e la Fenice vedrà alternarsi talenti vocali di tredici diverse nazionalità. Il senso di questi concorsi va oltre quello evidente di trovare cantanti in grado di affrontare ruoli wagneriani e dà la misura della ricchezza espressiva e della volontà di emergere di tanti giovani e meno giovani. Il Premio Venezia, nel novembre scorso, ne è stato un altro luminoso esempio con la vittoria della giovanissima pianista padovana Leonora Armellini. Pur di tutt’altro genere, un altro importante segno di ripresa lo porterà Maurizio Scaparro che firmerà il prossimo Carnevale, dal 23 al 28 febbraio, sotto il segno della Cina. Un ritorno in laguna graditissimo quello del regista, che ha costruito un Carnevale teatrale improntato sullo spettacolo e la cultura cinese in tutti i suoi aspetti, ma anche sull’immagine tradizionale che abbiamo di essa, con il recupero dell’immenso spazio dell’Arsenale. Manuela Pivato 3 Sommario / Contents 3 Editoriale Focus On 7 Splendida, unitaria e intensa «Walchiria» Tutta la forza drammaturgica dell’opera di Wagner alla Fenice A splendid, harmonious and intense «Walküre» The true dramaturgical strength of Wagner at the Fenice di / by Giuseppe Pugliese 11 7 Amore, fuoco e una spada invincibile «La Walchiria», prima giornata dell’«Anello del Nibelungo» Love, fire and an invincible sword «Die Walküre», the first «day» of «Der Ring des Nibelungen» 12 Il Wagner anti-monumentale di Jeffrey Tate Il direttore spiega la sua predilezione per intimità e dettagli Jeffrey Tate’s anti-monumental Wagner The conductor talks about his partiality for intimacy and details di / by Enrico Bettinello 16 Concerti, una mostra e un concorso Il fitto calendario delle «Giornate Wagneriane» Concerts, an exhibition and a competition The dense agenda of the «Wagnerian Days» All’Opera 18 19 18 Wolf-Ferrari, musicista cosmopolita «I quattro rusteghi» alla Fenice nel centenario della prima di Lucia Ludovica de Nardo La grande opera sorride ai più piccoli Le offerte formative della Fenice di Massimiliano Goattin La cornice sinfonica 20 A Michel Dalberto piace Brahms 21 Uno Schubert raffinatissimo e lirico 22 Alla ricerca di un Mozart ideale 21 Il meglio del pianista francese al Malibran di Arianna Silvestrini I «Sei momenti musicali» con l’Orchestra di Padova e del Veneto di Chiara Squarcina A Treviso l’Orchestra da Camera di Mantova e Alexander Lonquich di Chiara Squarcina Sacro e barocco 25 Il concerto per organo del Settecento: «ospite» a Venezia? di Corrado Cannizzaro Note veneziane 26 Mozart, un mese a Venezia 28 Premio Venezia, al pianoforte con sentimento 28 Il trionfo di Leonora 29 Ventisette concorrenti di ottimo livello 31 Suoni d’inverno 4 25 La felice transizione verso l’età adulta di Paolo Cattelan Barbara di Valmarana racconta la XXII edizione La tredicenne padovana ha vinto con Schumann Parla il presidente della giuria tecnica del Concorso La rassegna di Euterpe Venezia a Jesolo 26 Sommario / Contents 33 - 65 Della lirica, con passione 75 riflessioni sul teatro d’opera italiano a cura di Leonardo Mello e Ilaria Pellanda Contemporanea 67 A Treviso in punta di ballerine 69 Il mondo surreale e capovolto dei Momix 67 Straordinario spettacolo con gli angeli della danza internazionale di Elisa Guzzo Vaccarino A Mestre il nuovo spettacolo «Sun Flower Moon» di Susanne Franco L’altra musica 70 Fra versi e note, le creature sonore di Roberto Vecchioni 71 Franco D’Andrea, artista schivo e bon ton 72 Deep Purple, la fortuna sulle ceneri di un incendio 74 Cinque note italiane doc di John Vignola 70 Limpido jazz, ritmi complessi e forza tranquilla di Guido Michelone Dal rogo di Montreaux al successo di «Smoke On The Water» di Tommaso Gastaldi Nella rassegna di cantautori anche la Vanoni, Paoli e Vecchioni di Tommaso Gastaldi In vetrina 75 La «prima» della Fenice senza lustrini Inaugurazione sottotono tra striscioni e raccolta di firme contro i tagli Dintorni 78 Il Carnevale del Teatro secondo Scaparro 81 Un Carnevale nel segno di Dario Fo 82 Locanda e «Locandiera»: l’abilità di condurre gli uomini 81 La Cina è il tema-guida degli eventi della Biennale A Mestre un evento tutto cinese del Premio Nobel di Bruno Rosada Carta Canta 83 «il Patalogo», l’annuario che fa la storia del teatro 84 «IG»: da qui... all’inafferrabilità 85 Dal Venezuela al Canada: ecco l’eclettismo di Marco Castelli 86 87 Zoom a cura di Ilaria Pellanda Appuntamenti / Events 92 93 94 Gli appuntamenti del Carnevale del Teatro Il Veneto in Musica Dopo lo spettacolo / After the performance Il numero 28 promuove un’inchiesta sul ruolo della regia oggi 83 Il lavoro in fieri di Gianni Maroccolo e Ivana Gatti di Enrico Bettinello a cura di Ilaria Pellanda 84 5 Focus On Splendida, unitaria e intensa «Walchiria» Tutta la forza drammaturgica dell’opera di Wagner alla Fenice A splendid, harmonious and intense «Walküre» The true dramaturgical strength of Wagner at the Fenice di / by Giuseppe Pugliese* U O na delle esercitazioni predilette dai wagneriani del ne of the most favourite exercises of Wagnepassato – semplici amatori ma anche rians in the past – whether simple music lostudiosi – era il tentativo di stabilire una vers or scholars – was to establish a hierarchy gerarchia di valori fra le quattro parof values between the four parts of Der ti dell’Anello del Nibelungo, per acRing des Nibelungen, in an atcertare quale di esse fosse mutempt to ascertain which is musicalsicalmente la più grande. ly the greatest. With the excepEscluso L’Oro del Reno, a tion of Das Rheingold, causa, si pensi, persino probably due to its «brevity», della sua «brevità», la dithis discussion was limited sputa veniva limitata to the three Days. An aballe tre Giornate. Esercisurd and incomprehensible tazioni assurde e inexercise regarding the comprensibili, di una evaluation of materials critica contenutistica, and contents, even gastromaterialistica, diciamo nomical, without any pure gastronomica, meaning or value. Howepriva di qualsiasi signiver, what would be useful ficato e valore. Di una is the attempt to underqualche utilità, invece, stand for which reasons – sarebbe tentare di capire artistic, musical and dramaper quali ragioni – s’intenturgical – of the three Days, de ragioni artistiche, musiit is Die Walküre that is by cali e drammatiche – delle tre far the most frequently performed giornate, di gran lunga la più rapin Italy when the tradition prevaipresentata in Italia, quando impeled of separating the performances. rava il costume delle rappresentazioni However, I fear that not even this would separate, fosse la Walkiria. Temo, tuttavia, be particularly fruitful or reliable since this che l’accertamento sarebbe infruttuoso, coprimacy was linked to its performance in the Italian munque non attendibile, perché quel primato era legato language and the sad practice of numerous and considerable alla esecuzione in lingua italiana e alla triste consuetudine cuts (at times true acts of devastation) in the belief they would di numerosi, abbondanti tagli (talvolta autentiche devasimplify the dramaturgical rhythm of the poem, while actually stazioni) con i quali si riteneva di snellire il ritmo dramonly managing to disfigure it. maturgico del poema, ed invece si otteneva solo di sfiguThe problem is obviously a different one. Der Ring des Niberarlo. lungen was conceived as a unitary idea. Its dimensions and Il problema, naturalmente, è un altro. L’Anello del Nibedevelopment do not tolerate any division or mutilation, as is the lungo nasce, si realizza come concezione unitaria. Le sue case with Homer’s poems, La Commedia by Dante and Faust dimensioni, il suo svolgimento non sopportano suddiviby Goethe. As is the case with these gigantic constructions, we can sioni, né mutilazioni, proprio come i poemi omerici, la and must distinguish between structure and poetry in a Crocean Commedia di Dante, il Faust di Goethe. E come in queste manner in Der Ring des Nibelungen as well. And in Waggigantesche costruzioni anche nell’Anello del Nibelungo ner’s Saga in particular, these are and remain inseparable. Furpossiamo e dobbiamo distinguere, crocianamente, fra thermore, while Wagner did not discover «real time», as can be struttura e poesia. Le quali, pure, specie nell Saga wagneseen in the «length» of those poems, in Wagner’s scores it takes riana, sono e rimangono inseparabili. Inoltre il «tempo on a diverse dimension and application. This is because here it reale», pur non essendo una scoperta di Wagner, come has to take the musical tempo Boulez also spoke about into acdimostrano le «durate» di qui poemi, trova nelle partiture count as well, and which is resolved in what the profane call the di Wagner una diversa dimensione e applicazione. Perché mortal prolixity, the cruel, copious long-windedness of Wagner. qui deve fare i conti con il tempo musicale di cui parla Long-windedness and prolixity of which, in the integral version, anche Boulez, e che si risolve we also have several conspicuous in quelle che i profani chiaexamples in Die Walküre but *critico musicale, musicologo, fondatore e presidente mano le mortali lungaggini, which correspond to some of the dell’Associazione Richard Wagner Venezia le crudeli, fluviali prolissità greatest passages of this score, 7 Focus On di Wagner. Lungaggini e prolissità di cui, nella versione integrale, troviamo alcuni cospicui esempi anche nella Walkiria ma che si identificano con alcune delle parti più grandi di questa partitura, come conferma il racconto di Wotan al II atto. Ciò che la Walkiria rappresenta nell’Anello del Nibelungo sotto il profilo drammatico penso sia noto a tutti. Chiaro, più che nelle altre Giornate, lo svolgimento narrativo, chiarissima la vicenda, in gran parte esposta, con i lunghissimi antefatti raccontati, in particolare da Siegmund e da Wotan, meno da Brünnhilde, la vera protagonista di questa prima Giornata. Figlia prediletta di Wotan, eppure da lui punita per avere disobbedito ai suoi ordini (o meglio agli ordini di Fricka), volendo, in tal modo, obbedire alla vera volontà del padre suo. E se nel rapporto Sieglinde-Siegmund, con alcune delle pagine più dense di melos dell’intera Tetralogia, Wagner crea un biblico idillio amoroso fra i due fratelli, quale simbolo di un’innocenza primigenia, prima del peccato originale, nel rapporto Brünnhilde-Wotan, trascende persino questo ipotetico limite temporale per risalire alle lontananze mitiche degli intermundia lucreziani. La pietas dei greci, la compassione cristiana, la ritualità pagana confluiscono nel grandioso finale in cui, come già osservato, Brünnhilde da semplice simbolo si prepara, nella Giornata successiva, risvegliata da Siegfried, a diventare «universale umano». È un finale, il primo dei tre, che, in ordine drammaticamente crescente, condurrà a quello vittorioso del Siegfried, e a quello del Crepuscolo degli Dei che segna, con il crollo del Wahlalla la fine di tutte le cose, e con l’olocausto di Brünnhilde il ritorno alla innocenza primigenia. Con i suoi tre atti e le sue undici scene, lo svolgimento drammaturgico e musicale di questa Giornata appare saldamente rinchiuso nelle due poderose arcate del Preludio all’atto I e del grandioso finale, noto come l’Addio di Wotan, oppure Incantesimo del fuoco. All’interno di questi due formidabili blocchi musicali, gli episodi più conosciuti, amati, popolari: dal Winterstürme wichen (Canto della primavera) alla Cavalcata delle Walkirie, forse la pagina più amata, certo la più famosa della Walkiria, anche per le numerose, mutile versioni concertistiche che un tempo era consuetudine inserire nei programmi dei concerti sinfonici. Si tratta di due grandi episodi, ma nei quali un certo manieristico compiacimento liederistico nel primo, e il poderoso, rutilante carattere descrittivo, a tratti onomatopeico del secondo, così come taluni banali effetti esteriori dello stupendo finale dell’opera, offuscano, incrinano la loro indiscutibile grandezza 8 as can be seen in the tale by Wotan in act II. I believe that what Die Walküre represents in Der Ring des Nibelungen from a dramatic point of view is generally well known. The narrative development is clearer than in the other Days, the plot even more patent, and most of which is explained with a description of the lengthy background, in particular by Siegmund and Wotan, albeit less by Brünnhilde who is the real protagonist in the first Day. Wotan’s favourite daughter, but nevertheless punished by him for having disobeyed his orders (or rather Fricka’s orders), thus wanting to obey her father’s true wishes. And while with some of the pages that are the most dense in melos in the entire Tetralogy, with the Sieglinde-Siegmund relationship Wagner creates a biblical amorous romance between the brother and sister, a symbol of primeval innocence before original sin, the relationship between Brünnhilde-Wotan even transcends this hypothetical temporal limit and goes back to the mythical distance of Lucretian intermundia. Greek pietas, Christian compassion, pagan rituality all converge in the grandiose finale in which, as has already been noted, as a simple symbol, Brünnhilde prepares herself, in the following Day, to be reawakened by Siegfried and thus becoming a «universal human». It is this finale, the first of the three, that is to lead in a growing dramaturgical order, to the victorious one of Siegfried and to that of Die Götterdämmerung which, with the collapse of the Walhalla marks the end of everything, and with the holocaust of Brünnhilde, the return to primordial innocence. With its three acts and eleven scenes, the dramaturgical and musical development of this Day appears firmly enclosed in the two powerful passages in the Prelude to act I and the grandiose final, known as the Wotan’s Farewell or the Incantation of fire. These two formidable musical blocks include the most well-known, loved and popular passages: from the Winterstürme (Spring song) to the Ride of the Valkyries, perhaps the best-loved page and certainly the most famous in Die Walküre, also due to the numerous concert mutilations that once used to be added to the programmes of symphonic concerts. These are two majestic episodes, but ones in which their unquestionable musical greatness is obscured, impaired, by a certain liederistic complacency in the former, and by the powerful, fiery descriptive nature, with onomatopoeic parts in the second, as well as the at times banal exterior effects of the amazing finale of the opera. However, also in the case of Die Walküre, even in the form of a Focus On musicale. Comunque se una guida all’ascolto, anche della Walkiria, e sia pure come semplice suggerimento, pura indicazione, ha, deve avere uno scopo, a me pare che quello principale deve essere di evitare i «luoghi» più frequentati, conosciuti ed amati, per rivolgere la propria attenzione alle parti meno note, più nascoste, segrete della partitura, e su esse richiamare l’attenzione dell’ascoltatore. E allora comincerei con l’indicare tutto il II atto, il cuore drammaturgico della Walkiria, e uno dei punti capitali dell’intero Anello del Nibelungo. Sotto il profilo musicale è di una richhezza e di una bellezza che ne fa uno dei vertici dell’intera Saga, anche perché sorretto da un testo il cui valore letterario, poetico raramente Wagner avrebbe raggiunto nelle altre parti. Tale è quello del lunghissimo dialogo tra Wotan e Brünnhilde, esempio audacissimo di «tempo reale», e di autentica prosa musicale. Ad uguale altezza, ma forse musicalmente superiore, rimane il celebre Todesverkündingung, l’Annuncio di morte, nel breve dialogo tra Brünnhilde e Siegmund, un altro dei momenti sublimi di questa Giornata. Infine l’ultimo, grande dialogo fra Brünnhilde e Wotan (atto III, scena III). Avrei voluto, se il tempo e lo spazio me lo avessero consentito, indugiare in un’analisi particolareggiata, almeno di alcune parti di queste grandi scene. Purtroppo non mi è consentito, ed inoltre, prima di questa analisi testuale, avrei dovuto forse parlare più distesamente dei leitmotive nel linguaggio di Wagner, e della funzione drammaturgica ad essi assegnata; più propriamente del centinaio circa di nuclei motivici generatori, presentati, in gran parte, nell’Oro del Reno e nella Walkiria, e poi sottoposti, con una sapienza sconosciuta ad altri grandi musicisti, a continue trasformazioni e mutazioni. Avrei simple suggestion or indication, if a listener’s guide has, or has to have an objective, I believe it should be that of avoiding the most common, well-known and beloved «parts», and should focus on the lesser known passages, those that are less evident, the secrets of the score, and this is what the listener’s attention should be drawn to. And for me this is the entire second act, the dramaturgical heart of Die Walküre, and one of the crucial points in the entire Ring des Nibelungen. From a musical profile, it is of a richness and beauty that makes it one of the vertices of the whole Saga, also because the underlying text is of a literary and poetic value that Wagner did not often achieve in the other parts. For example the lengthy dialogue between Wotan and Brünnhilde, which is an audacious example of «real time», and of authentic musical prose. The famous Todesverkündingung in the brief dialogue between Brünnhilde and Siegmund, another of the sublime moments of this Day is just as outstanding and possibly even superior musically. Finally, the great dialogue between Brünnhilde and Wotan (act III, scene III). If both time and space had permitted, I would have liked to dwell on a detailed analysis of at least some of the parts of these great scenes. Unfortunately this was not the case and, furthermore, before undertaking any textual analysis, perhaps I should have spoken more about the leitmotive in Wagner’s language, and of the dramaturgical function they have; literally around one hundred generatory motif nuclei, most of which are present in the Rheingold and Die Walküre, and which are then submitted to constant transformations and changes with a skill unknown to other great composers. I should also have spoken about their more specific dramaturgically symbolic, mnemonic and even semantic function (therefore the very opposite of that aspiration to infinity, of that inexpressible poetry, of the poetics of the ineffable that the great Romantic composers pursued 9 Focus On anche dovuto parlare della loro più specifica funzione drammaturgicamente simbolica, mnemonica, addirittura semantica (l’opposto, quindi, di quella aspirazione all’infinito, di quella poesia dell’inesprimibile, di quella poetica dell’ineffabile che i grandi musicisti romantici perseguirono nelle loro opere), di questa funzione di richiamo, di memoria proustiana della sottile, saldissima rete da essi eretta intorno all’Anello del Nibelungo, e al suo interno, e come il loro essere e divenire si trasformi adeguandosi per l’inaudita coerenza dell’artista, alle caratteristiche musicali e drammaturgiche di ciascuna Giornata. Forse avrei dovuto fare tutto questo. Ma appartengo all’esigua schiera di quei wagneriani eterodossi che non ritengono indispensabile l’individiazione simbolica, drammaturgica, semantica di ciascun tema, della loro trasformazione, per poter godere degli sterminati panorami musicali di Wagner. Anzi, che ravvisano proprio in questa non necessità una delle ragioni più profonde della grandezza, dell’universalità della musica di Wagner, del suo linguaggio. Semmai richiamerei l’attenzione dell’ascoltatore sull’opportunità, se non proprio sulla necessità, specie per alcune parti dell’Anello del Nibelungo, e in particolare per quelle indicate della Walkiria, di una precisa conoscenza del testo, del suo significato logico, narrativo, e del suo valore letterario, poetico, drammatico. Sono questi soltanto alcuni, anche se fra i più significativi, degli esempi della altissima dignità letteraria, del valore poetico dei drammi wagneriani; quei testi, quei drammi sui quali, in connessione strettissima, in perfetta simultaneità, con una unità, un rapporto unico e inscindibile fra sillaba e nota, fra prosodia e musica, è nata la concezione del dramma musicale di Wagner, questo evento unico, isolato, irripetibile, e del quale la Walkiria, prima Giornata dell’Anello del Nibelungo, rappresenta una delle prove più splendide, unitarie, intense. Una esperienza, ancora oggi, anzi forse oggi più di ieri, fra le maggiori che un musicista, o un semplice amatore, possa compiere nel panorama della storia della musica. 10 in their works), of the function of evocation, the Proustian memory of the subtle, solid net they place around Der Ring des Nibelungen and within it, as well as how their being and becoming transforms itself by adapting themselves, with the unheard of coherence of the artist, to the musical and dramaturgical characteristics of each Day. Perhaps I should have dwelled on all these aspects. However, I belong to the small group of heterodox Wagnerians who do not believe the symbolic, dramaturgical and semantic identification of each theme or of their transformation to be indispensable for the enjoyment of the infinite musical panoramas of Wagner. On the contrary, I believe that the lack of this necessity is one of the most profound reasons for the grandeur, the universality of Wagner’s music and his language. At the most, I would draw the listener’s attention to the opportunity, if not the need, in particular in certain parts of Der Ring des Nibelungen, and for those indicated in Die Walküre especially, for an accurate knowledge of the text, of its logical and narrative significance, and of its literary, poetical and dramatic value. These are just a few examples, albeit some of the most important, of the highest literary grandeur, of the poetic value of Wagnerian drama; the texts, the dramas which led to the conception of Wagner’s musical drama, in the closest connection, in perfect simultaneity, with a union, a unique and inextricable relationship between each syllable and note, between prosody and music, resulting in this unique, isolated and unrepeatable event and which makes Die Walküre, the first Day of Der Ring des Nibelungen, one of the most splendid, harmonious and intense. Today, perhaps even more so than in the past, this is one of the greatest experiences that a musician, or a simple music lover can have in the panorama of the history of music. Qui e nelle pagine precedenti La Walchiria, litografie originali di Franz Stassen, cortesia del Centro Europeo di Studi e Ricerche Richard Wagner - Venezia. Focus On Amore, fuoco e una spada invincibile «La Walchiria», prima «giornata» dell’«Anello del Nibelungo» Love, fire and an invincible sword «Die Walküre», the first «day» of «Der Ring des Nibelungen» L D La vicenda Atto I. Nella capanna di Hunding e di sua moglie Sieglinde si rifugia uno straniero: è Siegmund, figlio di Wotan e di una mortale, che racconta come un giorno i nemici gli abbiano bruciato la casa e rapito la sorella. Hunding non gli nasconde di appartenere al popolo nemico, ma per la sacra legge dell’ospitalità aspetterà che passi la notte prima di battersi con lui. Mentre Hunding dorme, Sieglinde rivela allo straniero che un giorno un viandante (Wotan) ha infisso nel tronco di frassino del giardino una spada che avrebbe reso invincibile chi avesse saputo estrarla. L’uomo e la donna sono irresistibilmente attratti l’uno dall’altra e pur riconoscendosi come fratello e sorella cedono alla passione. Dopo che Siegmund è riuscito a estrarre dal tronco la spada i due fuggono. Atto II. Wotan invia Brünnhilde, la prediletta tra le Valchirie, in aiuto di Siegmund nel duello con Hunding. Interviene Fricka: Siegmund ha violato la sacralità del matrimonio con un incesto, dunque è lui a dover morire. Inoltre non comprende perché Wotan voglia far discendere da Siegmund e Sieglinde una stirpe di uomini liberi dalle leggi divine e dalla cupidigia. Wotan a malincuore impone a Brünnhilde di favorire la vittoria di Hunding. La Valchiria raggiunge Siegmund, pronto a uccidersi e a uccidere Sieglinde pur di non cadere nelle mani del nemico; vinta da queste parole disperate, si schiera al suo fianco. Wotan, adirato per essere stato disobbedito, spezza la spada di Siegmund, che cade trafitto, e subito dopo con disprezzo folgora Hunding; quindi, parte all’inseguimento di Brünnhilde, fuggita con Sieglinde per metterla in salvo. Atto III. Le Valchirie cavalcano nella tempesta scatenata dall’ira di Wotan senza osare difendere la sorella ribelle, che nel frattempo ha predetto a Sieglinde la nascita dal suo grembo di Siegfried, l’eroe che saprà riforgiare la spada di Siegmund con i resti da lei recuperati dal luogo del duello. Poi indica alla donna un rifugio nella foresta, nella quale Fafner, trasformato in drago, custodisce l’oro. Giunge Wotan per punire Brünnhilde: non più Valchiria ma donna, cadrà in un sonno magico e sarà preda di chi la desterà. Wotan accoglie la sua richiesta di erigerle attorno una barriera di fuoco che solo un eroe senza paura saprà attraversare; quindi l’addormenta con un bacio e invoca Loge perché il fuoco si levi. Synopsis Act I. A foreigner seeks refuge in the hut of Hunding and his wife Sieglinde: it is Siegmund, son of Wotan and a mortal; he describes how one day the enemy burnt down his house and kidnapped his sister. Hunding does not hide the fact he belongs to the enemy, but he will abide by the sacred laws of hospitality and wait until daybreak to fight with him. While Hunding is sleeping , Sieglinde tells the foreigner that one day, a traveller (Wotan) buried a sword in the tree trunk of an ash in the garden and that it would make whoever managed to draw it out invincible. The man and woman are irresistibly attracted to one another and although they realise they are brother and sister, they succumb to their passion. Once Siegmund has managed to draw the sword from the tree, the couple run away. Act II. Wotan sends Brünnhilde, the favourite of all the Valkyries, to help Siegmund in the duel with Hunding. Fricka intervenes: Siegmund has violated the sacred vows of marriage by committing incest, so it is he who should die. Moreover, she does not understand why Wotan will allow Siegmund and Sieglinde to produce a lineage of men free from divine laws and greed. Wotan reluctantly tells Brünnhilde to help Hunding win. The Valkyries reach Siegmund who is ready to kill himself and Sieglinde rather than fall in the hands of the enemy; overcome by such desperate words, she joins him. In a rage because he has been disobeyed, Wotan shatters Siegmund’s sword, and he falls injured to the ground, followed by Hunding who has been fatally injured. He then sets out to follow Brünnhilde who has fled with Sieglinde to protect her. Act III. The Valkyries are riding through the storm Wotan’s anger has aroused, without daring defend their rebel sister who has now foretold Sieglinde she will bear Siegfried’s child, the hero who will be able to forge Siegmund’s sword back together with the other pieces she retrieved from the site of the duel. She then shows the woman a shelter in the forest where Fafner, who has been transformed into a dragon, is guarding the gold. Wotan arrives ready to punish Brünnhilde: she will no longer be a Valkyrie but a woman; she will fall asleep under a spell and will be the quarry of whoever awakens her. Wotan grants her request to erect a barrier of fire around her, so that only a fearless hero will be able to pass; he then puts her to asleep with a kiss and invokes Loge to raise the fire. a Walchiria è la prima delle tre Giornate in cui si divide L’anello del Nibelungo, la saga scenica in una vigilia e tre giornate che Wagner compose, scrivendo di proprio pugno anche il libretto, elaborando alcuni cicli epici nordici, tra cui gli islandesi Edda e Völsunga Saga (sec. XIII). Le altre parti di cui è composto L’anello sono L’Oro del Reno (Vigilia), Sigfrido (Seconda Giornata), Il crepuscolo degli dei (Terza Giornata). ie Walküre is the first of the three Days which make up Der Ring des Nibelungen, the theatrical saga lasting an eve and three days, which Wagner not only composed but also wrote the libretto, basing it on several Norse epic cycles, including the Icelandic Edda and Völsunga Saga (XIII cent.). The other parts of Der Ring are Der Rheingold (Eve), Siegfried (second day), and Götterdämmerung (third day). 11 Focus On Il Wagner anti-monumentale di Jeffrey Tate Il direttore spiega la sua predilezione per intimità e dettagli Jeffrey Tate’s anti-monumental Wagner The conductor talks about his partiality for intimacy and details N ell’ambizioso progetto di allestimento della Tetralogia wagneriana che il Teatro La Fenice ha avviato in coproduzione con il Teatro di Colonia, spicca il sodalizio tra la regia di Robert Carsen e la direzione di Jeffrey Tate. Nato a Salisbury nel 1943, Tate è sicuramente tra i direttori più sensibili e esperti nel repertorio di Richard Wagner, avendo nel proprio curriculum la fondamentale esperienza di assistente di Pierre Boulez nello storico e discusso allestimento del Ring del centenario a Bayreuth. Artista poliedrico e dotato di una curiosità culturale vivacissima, che coltiva anche al di fuori dello stretto ambito musicale, Tate si sta preparando ad affrontare nuovamente Die Walküre, dopo averla diretta con successo recentemente al Teatro San Carlo di Napoli – con quell’allestimento, la Walküre veneziana condivide anche alcune voci fondamentali. Maestro, quale fu il suo primo «incontro» con Die Walküre e cosa la colpì della musica di Wagner? La prima volta che la ascoltai dovevo essere all’Università e deve essere stato al Covent Garden. Ricordo che non mi piacque molto, in modo particolare perché era un allestimento molto vecchio, non sapevo il tedesco I di / by Enrico Bettinello n the ambitious project for the production of the Wagnerian Tetralogy at the Teatro La Fenice, which you have started as a co-production with the Cologne Opera, the sodality between the production of Robert Carsen and the conductor Jeffrey Tate stands out. Born in Salisbury in 1943, Tate is surely one of the sensitive and skilled conductors in Wagnerian repertoire, since his curriculum includes the fundamental experience of acting as assistant to Pierre Boulez in the historic and very controversial production of the Ring at the Bayreuth centenary. A versatile artist and endowed with keen cultural curiosity which also goes beyond the musical sphere itself, once again Tate is getting ready to tackle Die Walküre, after his recent success conducting it at the Teatro San Carlo in Naples – and it is with that very production that the Venetian Walküre shares some fundamental voices. Maestro, when did you first «meet» Die Walküre and what was it that struck you about Wagner’s music? The first time I heard it I must have been at University and Die Walküre, Oper der Stadt Köln 12 Focus On e non capivo nulla del testo. Ho iniziato ad apprezzare Wagner più tardi, quando l’ho potuto ascoltare in inglese: la musica è meravigliosa, ma solo comprendendo le parole e l’insieme che formano con essa si può vivere davvero la grandezza di questi lavori. Dal mio iniziale scetticismo, mi sono gradualmente convertito, ho incominciato ad apprezzarlo, specie grazie alla direzione del grande Reginald Goodall. Nel 1976 lei ha avuto la fortuna di essere assistente di Boulez nei discussi allestimenti di Bayreuth. Quale segno ha lasciato in lei questa sorta di «specializzazione in Tetralogia»? Come può immaginare, si è trattato di un’esperienza straordinaria, che ho vissuto completamente, dall’inizio, dalle prove solo con il pianoforte e i cantanti. In quegli allestimenti la regia di Patrice Chéreau ha avuto per me un ruolo importantissimo, mi ha insegnato molto. Per quanto riguarda Boulez, si è creato un rapporto davvero unico ed è stato essenziale nell’indicarmi di percorrere sempre una visione che fosse mia. Il pubblico reagì in modo molto negativo, cosa che fu per noi un grande shock, dal momento che ci stavamo lavorando con tanto impegno, ma non abbiamo mai perso di vista la convinzione di stare facendo qualcosa di importante. Così, anno dopo anno, ho assistito al progressivo riconoscimento di quello che avevamo allestito e abbiamo ottenuto un successo incredibile. Dal punto di vista più strettamente musicale, da Boulez ho appreso come ascoltare un’orchestra, le sue strutture più intime, il bilanciamento e mi ha fatto fare le cose che volevo. A Bayreuth la regia era di Chéreau, a Venezia sarà di Robert Carsen, il cui Ring si può collocare in una linea ideale con quell’esperienza. Come si trova a lavorare con Carsen? Il nostro è un sodalizio molto forte, a Colonia, che si basa sul lavoro e su una grande complicità. Quello che mi piace di Carsen è che ha uno sguardo fresco e nuovo, ma anche la capacità di tenere sempre presente la linea narrativa: le persone che lui dirige sono «persone reali» e questo dona agli allestimenti la capacità di essere sempre attuali. È importante che i cantanti siano anche attori, non possono essere solo delle persone che stanno su un palco e cantano, per quanto bene. La visione di Carsen si fonde bene con il mio modo di leggere questo lavoro, evidenziando l’aspetto lirico, intimo, i dettagli della partitura: in Wagner ci sono grandi momenti, quelli che tutti conoscono, ma a me piace che la direzione non abbia un carattere titanico e monumentale, mi piacciono molto dei momenti che tanti giudicano secondari – penso ad esempio alla figura di Fricka – e che sono ricchi di dettagli affascinanti. Il suo rapporto con l’Italia è molto intenso. Ora sono qui a Napoli, dove rivesto il ruolo di direttore musicale e il mio legame con il vostro Paese è assolutamente unico, anche perché si tratta di una nazione dotata di una straordinaria musicalità. Sono molto contento e ansioso di venire a Venezia, perché ritengo che il tipo di lettura che daremo a Die Walküre sia particolarmente adatto a teatri come La Fenice, intimi, non troppo grandi, in grado di fare risaltare al meglio ogni sfumatura della musica. Quale attualità, in questi tempi segnati da conflitti e da grandi contraddizioni, continua a rivestire Die Walküre? Spesso si associa il nome di Die Walküre alla guerra, io credo che siano presenti in questo lavoro fortissimi Jeffrey Tate it must have been at Covent Garden. I remember that I didn’t like it very much, especially because it was an extremely old production, I couldn’t speak German and I didn’t understand the text at all. I began to appreciate Wagner later, when I was able to listen to it in English: the music was marvellous, but it is just by being able to understand the words and the work as a whole that one can truly experience the grandeur of these works. My initial scepticism gradually disappeared and I began to appreciate it, in particular thanks to the conductorship of the great Reginald Goodall. In 1976 you had the good fortune to act as assistant to Boulez in the controversial productions of Bayreuth. What mark did this «specialisation in Tetralogy» leave on you? As you can imagine, it was an extraordinary experience that I had from the very beginning, only with the rehearsals with the piano and the singers. The production by Patrice Chéreau played an extremely important role for me in those productions, I learned a lot from it. As regards Boulez, we formed a truly unique relationship and it played an essential role in making me understand I must always follow a vision that is my own. The audience reacted extremely negatively, which was a great shock to us, since we were working so hard on it, but we always held on to our belief that what we were doing was important. So, year after year, I have witnessed the gradual recognition of what we had produced and we have achieved unbelievable success. From a strictly musical point of view, Boulez taught me how to listen to an orchestra, its most intimate structure, the balance, and he let me do the things I wanted. In Bayreuth the production was by Chéreau, in Venice it will be by Robert Carsen, whose Ring can be considered to be in perfect line with that experience. What is it like working with Carsen? Our partnership in Cologne is very strong, and it is based on work and considerable complicity. What I like about Carsen is not only his new and fresh outlook, but also his ability to keep the narrative line in mind: the people he directs are «real people» and this ensures the productions are always up to date. It is important that the singers are also actors; they have to be more than just people standing on a stage singing, no matter how well. Carsen’s vision blends well with my way of interpreting this work, highlighting the lyrical, intimate aspect, the details of the score: in Wagner there are great moments, the ones everyone knows, but what I like is that the production is not of a titanic and monumental nature, I like the moments that many consider to be secondary – for example, I’m thinking of the figure of Fricka – and they are full of fascinating 13 Focus On Die Walküre, Oper der Stadt Köln elementi anti-guerra: viviamo in un periodo molto difficile e il lavoro di Carsen credo sia in grado di sottolineare bene come le tante guerre civili della nostra epoca siano causate da gente che vuole fare la guerra. Tutto il Ring è una grande riflessione sul potere, sulla perdita del potere, sull’uso che se ne fa e in un epoca come la nostra, che si confronta con il materialismo in maniera molto più intensa rispetto all’epoca in cui visse Wagner, ci si rende conto come questo lavoro sia stato scritto «per l’oggi». La grande attualità profetica del Ring è evidente nei tanti allestimenti di cui sentiamo oggi l’esigenza, la gente ne è affascinata e la possiamo comprendere appieno. Dopo Die Walküre a Veneiza, quali saranno i suoi prossimi impegni? Subito dopo Die Walküre sarò a Napoli per dirigere Le Nozze Di Figaro – è l’anno di Mozart – poi sempre in Italia ci sarà l’Ariadne Auf Naxos alla Scala e ancora Napoli con il Falstaff, ma in programma c’è anche una bella vacanza! la Locandina Teatro la Fenice – Venezia 25, 28, 31 gennaio, 2, 5, 7 febbraio Die Walküre musica di Richard Wagner regia Robert Carsen maestro concertatore e direttore Jeffrey Tate details. Your relationship with Italy is very intense. Now I am here in Naples, where I am acting as musical director and my link with your country is really unique, also because it is a country that is endowed with extraordinary musicality. I am really looking forward to coming to Venice, because I believe that our interpretation of Die Walküre is particularly suited to opera houses such as La Fenice, ones that are intimate, not too big, able to bring out the best of every shading of the music. Today, in a period marked by conflicts and great contradiction, what current topics does Die Walküre continue to have? Very often the name of Die Walküre is associated with war, I think that this work contains extremely strong anti-war elements. We are living in very difficult times and I think Carsen’s work is able to highlight very clearly how the many civil wars in our period have been caused by people who want to make war. The entire Ring is a great reflection on power, the loss of power, the use made of it and in times such as these, when the comparison with materialism is much more intense than in Wagner’s times, one realises that this work was written «for today». The considerable prophetical topicality of the Ring is clear in the many productions that we feel the need for today, people are fascinated by it and we understand that completely. What are your next commitments after Die Walküre in Venice? Immediately after Die Walküre I’ll be in Naples to conduct Le Nozze Di Figaro – it is Mozart’s year – then, still in Italy there’ll be Ariane Auf Naxos at La Scale and then back to Naples with Falstaff, but I’m also planning a nice holiday! 15 Focus On Concerti, una mostra e un concorso Il fitto calendario delle «Giornate Wagneriane» Concerts, an exhbition and a competition The dense agenda of the «Wagnerian Days» L e Giornate Wagneriane, organizzate dall’Associazione Richard Wagner di Venezia con il patrocinio del Casinò di Venezia, tra dicembre 2005 e febbraio 2006, si articoleranno in tre momenti distinti e correlati, che anticiperanno e incorniceranno la rappresentazione della Valchiria alla Fenice. Il primo di questi è ovviamente il V Concorso Internazionale per Voci Wagneriane. Alessandra Althoff, incaricata dell’Associazione per la programmazione e la gestione dei borsisti, ci spiega con precisione il funzionamento della gara: «Nella semifinale che si svolgerà al Teatro Malibran il 1 febbraio si alterneranno, accompagnati al pianoforte, 18 candidati di 13 diverse nazionalità, prescelti quest’estate a Bayreuth, e presentati da 17 Associazioni internazionali tra le 50 che hanno inviato propri candidati. Queste Associazioni fanno parte della Richard Wagner International Association, che ha 150 affiliate in tutto il mondo». Da questi 18, 8 verranno scelti dalla giuria per la finale alla Fenice (4 febbraio), dove ad accompagnarli sarà l’orchestra del Teatro La Fenice diretta da Christoph Ulrich Meier, primo assistente musicale del Bayreuther Festspiele. Già a dicembre intanto era cominciato il ciclo dei «Giovani concertisti», dedicato ai talenti vocali emergenti che continuerà, al Salone delle Feste di Ca’ Vendramin Calergi il 20 gennaio, con una serata intitolata alla «Vocalità wagneriana nell’opera francese», che vedrà il soprano Marianne Gesswagner e il mezzosoprano Aurelia Varak cimentarsi nelle musiche, tra gli altri, di Massenet, Berlioz e Halévy. L’appuntamento finale della serie concertistica, previsto per il 3 febbraio al Malibran, è infine dedicato a Wolfgang Wagner e ospiterà il pianista Detlev Eisinger, impegnato nell’esecuzione di brani di Wagner/Liszt, Wagner/Wolf e dell’«Intermezzo sull’abisso» di Paolo Furlani. «I concerti – precisa il presidente e fondatore dell’Associazione veneziana Giuseppe Pugliese – sono 16 O rganised by the Richard Wagner Association in Venice between December 2005 and February 2006, the Wagnerian Days will be structured in three distinct but correlated events that will anticipate and act as background for the performance of Die Walküre at La Fenice. The first of these is obviously the V International Competition for Wagnerian Voices. Alessandra Althoff, who is responsible for the Association’s planning and management of the bursars, gave us a detailed explanation of how the competition works: «In the semi-finale, which will take place at Teatro Malibran on February 1st, there will be 18 candidates from 13 different countries, accompanied by the piano and selected last summer in Bayreuth, and they are being presented by 17 of the 50 international Associations who are sending their own candidates. These Associations all belong to the Richard Wagner International Association, which has 150 members worldwide». Of these 18, 8 will be chosen by the jury for the finale at La Fenice (February 4th), where they will be accompanied by the orchestra of the Teatro La Fenice and conducted by Christoph Ulrich Meier, musical Richard Wagner assistant of the Bayreuther Festpiele. The cycle of the «Young concert artists» already began in December and was dedicated to up and coming vocal talents and will continue at the Salone delle Feste at Ca’ Vendramin Calergi on January 20th, with an evening called «Wagnerian voices in French opera». The soprano Mariane Gesswagner and the mezzosoprano Aurelia Varak will perform music by Massenet, Berlioz and Halévy and other composers. The final appointment of this concert series is to be held on February 3rd at the Malibran, and will be dedicated to Wagner and with the pianist Detlev Eisinger, who will play passages by Wagner/ Liszt, Wagner/Wolf and the «Intermezzo sull’abisso» by Paolo Furlani. «The concerts – Ms. Althoff continues – are also an occasion to present our bursars. I think it is important to underline that ever since the Association was founded in ’92, we have sent almost 50 young artists throughout the Focus On anche un’occasione per far conoscere i nostri borsisti. Ci tengo a sottolineare infatti che da quando è stata fondata l’Associazione nel ’92 abbiamo mandato in giro per il mondo quasi 50 giovani artisti, e tutti, nelle diverse discipline, hanno avuto la possibilità di emergere». E a riprova di questo la signora Althoff racconta la storia di Anja Kampe, fresca di un importante debutto a Bruxelles: «Lei è stata nostra borsista nel ’99 e ha poi partecipato al III Concorso per Voci Wagneriane nel 2000, vincendo il premio del pubblico. È stato grazie a questo che ha cambiato repertorio (prima si dedicava al repertorio lirico leggero) e Die Walküre, Bayreuth 1876 si è resa conto delle sue reali potenzialità espressive. Per poter affrontare e sostenere un ruolo wagneriano, infatti, oltre alle difficoltà musicali e drammaturgiche, bisogna sviluppare la consistenza e la tecnica vocale lentamente. Quando, dopo un percorso durato anni, ha cominciato a credere veramente nelle sue forze, e ha iniziato una carriera fulminante, è stata anche per noi un’enorme soddisfazione». La terza parte di cui si compongono le Giornate Wagneriane è infine la mostra «Wagner Visivo: La Walküre tra Franz Stassen e Arthur Rackham» che sarà promossa dal Centro Europeo di Studi e Ricerche Richard Wagner (C.E.S.R.R.W., sorto nel ’94 all’interno dell’Associazione lagunare) in collaborazione con l’Università di Venezia e quella di Bayreuth, dove esiste l’unico centro per lo studio del teatro musicale d’Europa. «Sarà un’esposizione basata sulle 26 litografie – che la nostra Associazione ha la fortuna di possedere – che Franz Stassen fece sul tema della Valchiria wagneriana. Vi sarà posto anche per una stazione multimediale – realizzata in collaborazione con l’Università di Venezia e il Centro formativo-didattico del Teatro La Fenice – dove si confronteranno le immagini di Stassen con il ciclo analogo dell’illustratore narrativo inglese Arthur Rackham, anch’egli impegnato sullo stesso soggetto, cui ha dedicato 17 opere». (l.m.) world and all of them have had the possibility to excel in various disciplines». The story of Anja Kampe with her recent important debut in Brussels is confirmation of this: «She was one of our bursars in ’99 and she went on to participate in the III competition of Wagnerian Voices in 2000 and win the general prize. It was thanks to this that she changed her repertoire (she mainly concentrated on light operatic repertoire) and realised the extent of her true expressive potential. Indeed, to be able to tackle and sustain a Wagnerian role, apart from the musical and dramaturgical difficulties, the slow development of the consistency and vocal technique is also necessary. After years of training, she truly began to believe in her strength and began an amazing carrier which was a great satisfaction for us as well». The third part of the Wagnerian Days is the exhibition «Visual Wagner: Die Walküre by Franz Stassen and Arthur Rackham» which will be promoted by the Richard Wagner Centre of Studies and Research (founded in ’94 as part of the Venice Association) together with the University of Venice and Bayreuth, the latter boasting the only centre for the study of theatre music in Europe. «The exhibition will be based on 26 lithographs – which our Association is lucky to own – created by Franz Stassen on the subject of Wagner’s Walküre. There will also be a multimedia station – created in collaboration with the University of Venice and the Educational Centre of the Teatro La Fenice – which will offer images by Stassen with the analogue cycle by the English narrative illustrator, Arthur Rackham, who also created 15 works on the same subject». (l.m.) La giuria del V Concorso Internazionale per le Voci Wagneriane è composta da Eberhard Friedrich, Maestro del Coro Bayreuther Festspiele e Staatsoper Berlin; Dorothea Glatt, Consulente Artistico Opera Toronto e Royal Opera Stockholm; Eva Maertson, Soprano e Vicepresidente Richard Wagner International (R.W.I.) e docente Hochschule für Musik Hannover; Ute Priew, mezzosoprano Bayreuther Festspiele e docente Hochschule für Musik Berlin; Giuseppe Pugliese, musicologo, critico musicale e presidente Associazione Richard Wagner Venezia (A.R.W.V.); Alessandra Althoff, Soprano e docente Sommerakademie Universität Mozarteum Salzburg e Accademia Villa Ca’ Zenobio – Treviso. 17

Scaricare