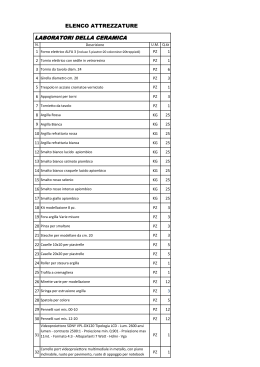

CDS 396/1-2 DIGITAL LIVE RECORDING GAETANO DONIZETTI (Bergamo, 1797 - Bergamo, 1848) LA ZINGARA Opera semiseria in two acts Libretto by Andrea Leone Tottola (Score revision by Anders Wiklund) Argilla (mezzo) Manuela Custer Papaccione (baritone) Domenico Colaianni Ines (soprano) Rosita Ramini Fernando (tenor) Massimiliano Barbolini Don Sebastiano Alvarez (baritone) Pietro Terranova Duca D’Alziras (tenor) Cataldo Gallone Amelia (soprano) Sara Allegretta Ghita (soprano) Roberta Zaccaria Manuelitta (soprano) Giulia Petruzzi Antonio Alvarez (baritone) Sguiglio (baritone) Giacomo Rocchetti Massimiliano Chiarolla Don Ranuccio Zappador (baritone) Filippo Morace BRATISLAVA CHAMBER CHOIR Chorus master: Pavol Procházka ORCHESTRA INTERNAZIONALE D’ITALIA Conductor: Arnold Bosman CD 1 1 Prelude 73'11" 01'56" ACT ONE 2 Dell'ospite illustre (Chorus) 3 Al piacer, che spira intorno (Ranuccio) 4 Il Duca di Alziras (Antonio and Amelia) 5 Mi è dato alfine (Ranuccio) 6 Donzelle! A penetrar (Argilla) 7 Orsù Argilla (Argilla) 8 Quid est homo sine femina? (Papaccione) 9 E via Papaccione (Argilla) 10 Se il cielo permetterà (Sebastiano) 11 Se un lampo passegger (Sebastiano) 12 Perché non basto a frangervi (Sebastiano) 13 Gli astri di Venere (Argilla) 14 Coraggio Don Fernando! (Argilla) 15 Costei mi sorprende! (Fernando) 16 Donna, dilegua i miei dubbi (Fernando) 17 Ecco un pugnal… su… celalo… (Ranuccio) 18 Ah vile! Ah iniquo Antonio (Ranuccio) 19 Ah, mostro! (Argilla) 20 Ah! Come sul mattin (Ines) 21 Ma zitto! (Amelia) 22 Feste, gioje, delizie, piaceri (Chorus) 23 Basta, o amici; ah troppo cari (Duca) 24 Papaccione Cincorenza (Papaccione) 25 Se un cor magnanimo (Argilla) 26 La nostra gioia accresca (Duca) 02'14" 05'28" 02'38" 00'45" 04'54" 00'23" 06'45" 04'52" 02'45" 03'02" 05'10" 01'50" 02'28" 02'48" 01'58" 03'28" 02'23" 01'46" 02'38" 02'57" 01'07" 02'21" 01'58" 02'10" 02'15" CD 2 ACT TWO 1 Addò mmalora la trovo? (Sguiglio) 2 Lascia, che io taccia (Fernando) 3 Un mentitor mi credi? (Fernando) 4 Se è ver, che in Ciel si formano (Fernando, Ines) 5 Fernando? (Argilla) 6 Scendi, scendi Papaccion (Chorus) 7 Che brutte vuce (Papaccione) 8 Mo! Aspetta, e bì che pressa! (Papaccione) 9 Non c'è tempo da perdere (Argilla) 10 Oh colpo! Io fui tradito! (Ranuccio) 11 Mi straziano il petto (Ranuccio) 12 Disgraziato! Come hai potuto? (Ranuccio) 13 Miralo: è il tuo germano (Sebastiano) 14 E' tenero il pianto (Fernando, Sebastiano, Duca) 15 Ma dimmi… e da qual mano (Duca) 16 Eccellenza, vengo a conoscere (Ranuccio) 17 Tu l'autor de' miei giorni? (Argilla) 18 E fia ver? Di sì gran dono (Argilla) 19 Sì! Mi stringi o padre al seno (Argilla) 20 Ah! Dopo il fiero nembo (Argilla) 47'56" 00'56" 00'37" 04'28" 04'31" 02'12" 00'26" 00'22" 05'23" 02'15" 03'26" 01'51" 01'27" 04'00" 02'05" 03'19" 02'05" 00'29" 02'07" 01'44" 04'01" opo il successo de Il Fortunato Inganno (1823), la partitura giovanile di Donizetti messa in scena a Martina Franca nel 1998 e coronata dall’assegnazione del Premio Abbiati, abbiamo voluto continuare la nostra riscoperta del primo Donizetti con La Zingara, composta un anno prima anch’essa a Napoli. L’importanza di quest’opera nel percorso stilistico del compositore di Bergamo è ampiamente illustrata nelle note di presentazione. Le rappresentazioni del luglio 2001 ci hanno rivelato, ancor più della semplice lettura della partitura, l’originalità di questo libretto e la sovrapposizione di generi musicali presenti in Napoli, una capitale dai teatri lirici freneticamente attivi dove diverse culture ed estetiche contrastanti si incontravano continuamente. La Zingara è innanzitutto un personaggio straordinario, senza dubbio il primo, nella carriera di Donizetti, a lasciar intravedere le future grandi eroine della maturità. E’ buffo e serio ad un tempo, con quel pizzico di follia che sarà in seguito frequente in molte composizioni donizettiane. Il libretto, che segue le regole della commedia napoletana, ha l’originalità di mettere in scena personaggi che si esprimono in dialetto assieme ad altri dal profilo aristocratico, la cui aulicità ricorda i grandi classici, specialmente Gluck e Beethoven. Il ricco cast vocale richiesto da La Zingara (1 mezzosoprano, 4 soprani, 2 tenori e 6 baritoni), con parti per la maggior parte dei solisti che sono di una difficoltà oggi quasi insormontabile anche per i grandi allestimenti internazionali, testimonia la straordinaria fioritura della scuola del belcanto in quel periodo. La decadenza di Napoli e del suo Conservatorio, che comincia a manifestarsi già verso il 1820, obbligherà Donizetti a mostrarsi in seguito più saggio e ad adattare meglio le sue intenzioni a prototipi vocali più circoscritti, come nel buffissimo Elisir d’amore o ne La Figlia del reggimento. Questa registrazione, presa dal vivo, conserva intatta la vitalità straripante della messa in scena dal ritmo indiavolato di Marco Gandini, assistente privilegiato di Franco Zeffirelli, pur rivelando qualche volta le piccole incertezze di un cast di giovani solisti che in alcuni casi non avevano mai vissuto una simile esperienza. Dal 1994 il Festival di Martina Franca non fa che confermare la sua volontà di riscoprire opere dimenticate affidandone l’esecuzione a dei giovani che potrebbero diventare le stelle di domani. D Sergio Segalini Direttore Artistico del Festival di Martina Franca 4 fter the success of Donizetti’s Il Fortunato Inganno (1823), staged in Martina Franca in 1998 and crowned by the Premio Abbiati award, we have continued our rediscovery of the early stages of this composer’s career with La Zingara, written one year earlier also in Naples. The importance of this opera in the development of the composer’s style is amply explained in the liner notes. The performances of July 2001 have revealed, much more than a simple reading of the score, this libretto’s originality and the mixture of music styles present in Naples, a capital with frenetically active lyrical theatres where different cultures and contrasting aesthetics continually met. The character of the Gypsy is quite extraordinary and the first to give us a hint of the great heroines to come in Donizetti’s maturity. It is buffo and serio at the same time, with that touch of folly that will be frequent in many of Donizetti’s later compositions. The libretto follows the rules of Neapolitan comedy and has the peculiarity of putting together characters that express themselves in dialect with others by the more aristocratic profile, whose stateliness calls to mind the great classics, especially Gluck and Beethoven. The rich vocal cast of La Zingara (1 mezzo, 4 sopranos, 2 tenors and 6 baritones), with some solo parts that today would be considered of almost unsurmountable difficulty even for more experienced singers, witnesses to the extraordinary flourishing of belcanto in those years. However the decadence of Naples and of its Conservatory, which began around 1820, would force Donizetti to take a wiser attitude and look for more circumscribed vocal prototypes for his later operas, like the very funny Elisir d’amore or La Figlia del reggimento. The present live recording preserves all the overflowing vitality of the mise-en-scène of Marci Gandini (a privileged collaborator of Franco Zeffirelli), by the frenzied rhythm, although it sometimes also reveals the few slight uncertainties of a cast of young soloists who, in some cases, had never lived a similar experience before. Since 1994 the Festival of Martina Franca has constantly reasserted its desire to rediscover forgotten masterpieces and to entrust their interpretation to young performers, who might well be tomorrow’s stars. A Sergio Segalini Artistic Director of the Festival of Martina Franca 5 ach dem Erfolg von Il Fortunato Inganno (1823), dem in Martina Franca 1998 aufgeführten und mit dem Premio Abbiati ausgezeichneten Jugendwerk Donizettis, wollten wir unsere Wiederentdeckung der ersten Werke des Komponisten mit La Zingara fortsetzen, einer ein Jahr zuvor ebenfalls in Neapel geschriebenen Oper. Deren Bedeutung in der stilistischen Entwicklung Donizettis wird in den Anmerkungen in diesem Beiheft ausführlich dargelegt. Die Aufführungen im Juli 2001 zeigten uns - mehr noch als die einfache Lesung der Partitur - die Originalität dieses Librettos und die Mischung der in Neapel vertretenen Musikgenres. In dieser Stadt standen einander überaus geschäftige Opernhäuser gegenüber, in denen verschiedene Kulturen und widersprüchliche ästhetische Auffassungen ständig aufeinandertrafen. Die Titelrolle ist vor allem einmal eine außerordentliche Figur, in Donizettis Laufbahn zweifellos die erste, an der die künftigen großen Heroinen seiner reifen Jahre schon zu ahnen sind. Sie ist gleichzeitig lustig und ernst und besitzt jenen Hauch Verrücktheit, der in vielen Kompositionen Donizettis später häufig auftreten sollte. Das Libretto folgt den Regeln der neapolitanischen Komödie und bringt originellerweise Personen auf die Bühne, die Dialekt sprechen und auf andere adeliger Herkunft treffen, deren aulicità an die großen klassischen Komponisten, speziell Gluck und Beethoven, erinnert. Die von La Zingara benötigte umfangreiche Besetzung (1 Mezzo, 4 Soprane, 2 Tenöre, 6 Baritone), deren Rollen zum Großteil für die Solisten heute (auch für die großen, gut bestückten internationalen Häuser) fast nicht zu bewältigende Schwierigkeiten bereithalten, bezeugt die außerordentliche Blütezeit der damaligen Belcantoschule. Der Verfall Neapels und seines Konservatoriums, der sich bereits gegen 1820 anzukündigen beginnt, sollte Donizetti dazu zwingen, sich später als schlauer zu erweisen und seine Absichten auf genauer umschriebene Stimmfächer zu beschränken, wie im als buffissimo empfundenen Liebestrank oder in der Regimentstochter. Diese Liveaufnahme behält die überbordende Vitalität der Regie von Marco Gandini (Franco Zefirellis liebstem Regieassistenten) bei, obwohl manchchmal die kleinen Unsicherheiten einer aus jungen Sängern, die in einigen Fällen erstmals eine derartige Erfahrung machten, bestehenden Besetzung zu hören sind. Seit 1994 bekräftigt das Festival von Martina Franca seinen Willen nach Neuentdeckung vergessener Opern, deren Wiedergabe jungen Sängern anvertraut wird, die zu den Stars von morgen werden könnten. N Sergio Segalini Künstlerischer Leiter des Festivals von Martina Franca 6 près le succès de Il fortunato inganno (1823), partition de jeunesse de Donizetti à l’affiche du Festival de Martina Franca en 1998, succès couronné par le prix Abbiati, nous avons voulu poursuivre notre redécouverte avec La Zingara, créée un an plus tôt, également à Naples. Le texte de présentation de cet enregistrement rappelle l’importance de l’ouvrage dans l’évolution stylistique du compositeur de Bergame. Les soirées de juillet 2001 nous ont révélé, encore plus que la simple lecture de la partition, l’originalité du livret et le mélange des genres musicaux, dans une capitale où des cultures différentes et des esthétiques opposées s’affrontaient en permanence dans des théâtres lyriques à l’activité débordante. La Zingara est d’abord un personnage extraordinaire, le premier sans doute, dans la carrière de Donizetti, à annoncer les futures grandes héroïnes de la maturité. Elle est buffa et seria à la fois avec ce grain de folie qui hantera tant de compositions du musicien. Le livret, qui obéit aux règles de la comédie napolitaine, a l’originalité de confronter des personnages s’exprimant en dialecte avec des figures aristocratiques dont l’aulicità rappelle les grands classiques, Gluck et Beethoven essentiellement. L’importante distribution exigée par la Zingara (1 mezzo, 4 soprani, 2 ténors et 6 barytons) témoigne de l’extraordinaire floraison de l’école du bel canto, la plupart des solistes affrontant des airs d’une difficulté souvent insurmontable de nos jours, même pour les grandes et fortunées scènes internationales. La décadence de Naples et de son Conservatoire, qui annonce déjà en ces années 1820, obligera Donizetti à se montrer plus sage par la suite et, surtout, à mieux cibler son propos, comme dans le buffissimo Elisir d’amore ou La Fille du régiment, aux prototypes vocaux bien plus faciles à cerner. Cet enregistrement, capté sur le vif, préserve la vita- lité débordante de la mise en scène de Marco Gandini, assistant privilégié de Franco Zeffirelli, au rythme endiablé, et accuse par moments les incertitudes d’un plateau de jeunes solistes qui, pour certains, n’avaient jamais connu d’expérience similaire. Depuis 1994, le Festival de Martina Franca ne fait que confirmer sa volonté de redécouvrir des opéras oubliés, en les confiant à des jeunes qui pourraient devenir les stars de demain. A Sergio Segalini Directeur Artistique du Festival de Martina Franca 7 Manuela Custer (Argilla), Domenico Colaianni (Papaccione) ricca di temi e intrighi da essere, come qui, sunteggiata nella sua molteplicità da un modello originale (La petite bohémienne, mélodrame in 3 atti in prosa di Louis Charles Caigniez, rappresentato a Parigi, 1816). Tottola traduce in napoletanità quando il discorso è affidato ai due buffi e, dalle tante peripezie, fissa gli episodi destinati alla musica (12 numeri) e li spinge verso una identificazione operistica, seria o giocosa. Coglie il personaggio e ruolo calamitante della zingara, Argilla: figuretta dominatrice, brillante e scaltra, s’aggira in un castello in festa per l’annunciato arrivo del Viceré e col pretesto di predire i destini scopre i segreti di tutti e li dipana. Unisce la coppia di giovani innamorati in difficoltà, sventa il delitto ordito dal signore del castello contro il Viceré e smaschera il sicario, scopre nel sotterraneo un nobile prigioniero e per liberarlo abbindola il carceriere inscenando una discesa agli inferi nella cisterna alla ricerca di un tesoro. Alla fine la generosa risolutrice della pièce à sauvetage scopre di essere la figlia, perduta bambina, del nobile prigioniero. Donizetti la investe di un soffio nuovo e ne fa un’incantevole e misteriosa creatura, viva nella magica penombra di sorriso e di predizione vagabonda, lo sguardo allungato all’indietro verso le zingare di Paisiello (del 1789 I zingari in fiera, su libretto di F. Cerlone) e aperto in avanti allo spirito dei tempi che stimola a cercare l’elemento spagnolo e zingaresco, dalle ballate del Berchet o del Carrer, al romanzo di Manzoni, a Verdi. Il personaggio della zingara diventa anche musicalmente l’elemento legante e unificante di una struttura a numeri musicali separati dai dialoghi in prosa. Fa il suo ingresso dopo il Coro e scena d’introduzione (n. 1): preparativi di festa al castello, messaggio garbato dall’ospite atteso che suscita reazioni enigmatiche, e una bella fanciulla infelice (soprano). Urge aiuto. Si presenta la Zingara (mezzosoprano) con la Seduzione e mistero della zingarella di Donizetti a Zingara (Napoli, 12 maggio 1822) è il primo incontro operistico di Gaetano Donizetti con la città e teatralità napoletana. Giovane (ventiquattro anni), gioioso della carriera da poco intrapresa e caricato dal successo appena ottenuto a Roma (Zoraide, gennaio 1822), fedele alla qualità di scrittura del suo maestro Mayr e al prestigio che gliene deriva, Donizetti si tuffa nel tessuto teatrale napoletano con la destrezza istintiva di chi salta su un cavallo in corsa. E subito fa centro (52 rappresentazioni da maggio a ottobre 1822), innesca quel processo di identificazione con la città che lega il compositore bergamasco a Napoli fino al 1838. L’opera è scritta per il Teatro Nuovo sopra Toledo, destinato prevalentemente al repertorio buffo, prosa compresa. Vi si parlava napoletano quando s’aprì, nel 1724; lo si parla ancora al tempo di Donizetti, confinato nelle parti dove la napoletanità schietta è carattere del personaggio affidato al buffo napoletano: numeri musicali e dialoghi in prosa. Quando Donizetti arriva, la tradizione del buffo napoletano è legata alla famiglia dei Casaccia, attivi dal 1749 e arrivati in quegli anni alla terza e quarta generazione, con Carlo che nella Zingara interpreta Papaccione, custode delle prigioni che si lascia burlare, e suo figlio Raffaele, da poco avviato a piccole parti, che interpreta il servo Sguiglio. Il contatto coi cantanti buffi è il primo filo diretto tra Donizetti e la napoletanità: s’affida alla loro complicità col pubblico, entra nel loro guizzo inventivo e mimico, nell’immediatezza del linguaggio rapido e salace. Il libretto di Andrea Leone Tottola risponde al gusto dell’opera a peripezia, diventata così smisuratamente L 9 Cavatina ammaliatrice (“Donzelle! a penetrar / l’arcan del vostro cor”) (n. 2). Canta il Duetto col buffo Papaccione (n.3) adescando il babbeo con femminilità sorridente che precorre lo scintillio del duetto tra Dulcamara e Adina nell’Elisir d’Amore, ed anticipa un tema del duetto tra Dulcamara e Nemorino (stretta). Assiste non vista all’Aria con le catene (n. 4) del prigioniero Sebastiano (basso), scena tipica del teatro barocco rinnovata con dolente e appassionata cantabilità. Innamorati, prigionieri e macchinazioni di potenti portano le forme dell’opera seria; alla zingara la funzione di collegarle al semiserio. Si accosta a Fernando (tenore) dopo la sua Cavatina (n. 5) e avvia un terzettino con lui e il servo Sguiglio. Assiste, non vista, ai propositi di congiura di Don Ranuccio Zappador (basso) contro il Duca d’Alziras, l’ospite atteso: aria “Ecco un pugnal, su celalo” (n. 6). Concerta il Finale (n. 7) del primo atto, dove i personaggi, a coppie, snodano un Sestetto incantato (gli innamorati), parodiato (nel controcanto di corteggiamento di servo e nutrice), saltellante di furtivi preparativi di incantesimo (Argilla a Papaccione). E quando l’inganno sta per essere scoperto dalla nutrice infuriata, arriva il corteo del Duca e la zingarella si ricicla a tutto splendore con una lunga frase e riverenza: “Se un cor magnanimo tu chiudi in petto / (…) / La gioia, il giubilo ti siede a lato…”. L’atto secondo si apre con un duetto di contrasto e amore fra gli innamorati (n. 8). Sopraggiunge la zingara per il Coro ed Aria di Papaccione che scende nella cisterna (n. 9): la scena di discesa agl’Inferi e Coro di Spiriti, cara all’opera barocca e parodiata nell’opera buffa, prende il suo spazio su un rapido spunto del Caigniez, occasione alle scene di paura del buffo e al Coro sotterraneo, in parodia dantesca. Il Settimino (n. 10) sorprende i personaggi in situazione di sospesa incertezza, dopo il delitto sventato, il pri- gioniero misteriosamente scomparso, il cattivo confuso; Donizetti dimentica la fragilità dell’opera buffa e tocca in profondo, con mano lieve e sapiente, con andamento di grande intensità nella melodia che si fa strada. Fu il pezzo più ammirato e si racconta che Bellini, allora allievo del Collegio di San Sebastiano lo studiava e suonava ogni giorno. La struttura musicale prosegue con l’Aria drammatica di Ines (non numerata), la fanciulla innamorata che il padre contrasta; quindi col Terzetto “Miralo, è il tuo germano” (n. 11), dove il generoso Fernando viene riconosciuto salvatore e le trame di Zappador sono scoperte. E’ il momento della resa dei conti, in prosa. La zingarella, che tutto ha condotto a buon fine, si affaccia per l’applauso. Ritrova il padre nel nobile prigioniero che ha salvato e chiude l’opera da dominatrice, con recitativo d’affetti e un Rondò brillante (n. 12) che dispensa a tutti felicità. Franca Cella 10 and intrigues that these were often - like in this case summarised from the original model (for this opera La petite bohémienne, a three-act mélodrame in prose by Louis Charles Caigniez staged in Paris in 1816). Tottola entrusted the comic parts to the salacity of the Neapolitan dialect and chose 12 out of the many vicissitudes as music numbers, giving them an operatic identity, either serious or comic. He grasped the importance and pivoting role of the title character, the gypsy girl Argilla: a dominant figure, brilliant and cunning, she roams around a castle where everyone is preparing for the visit of the Viceroy and, on the pretext of foreseeing the people’s future, unveils their secrets and solves their problems. Thus she unites the contrasted lovers; foils the plot of the castle’s master against the Viceroy and unmasks the wouldbe killer; discovers a noble prisoner kept in the castle’s dungeons and to free him tricks the warder, sending him on a treasure hunt to the “infernals”. In the end this generous solver of the pièce à sauvetage has her reward when she finds out that her lost father, from whom she had been kidnapped as a child, is none other than the noble prisoner she has saved. The composer revived this character and transformed it into a charming and mysterious Donizettian creature, who comes to life with her magic winking and wanderer’s predictions; he moulded it casting a glance back on Paisiello’s gypsies (I zingari in fiera, 1789, on a libretto by F. Cerlone) but also forward, anticipating the Spanish and gypsy element that will be found in Berchet’s and Carrer’s ballads, Manzoni’s novels, and Verdi. Argilla, moreover, is the musically unifying element in a structure that consists of numbers separated by dialogues. The gypsy makes her entrance after the introductory chorus and scene (No.1), which present the preparations for the feast in honour of the coming guest; his Donizetti’s charming and mysterious gypsy a Zingara (The Gypsy, Naples, 12th May 1822) was Gaetano Donizetti’s first encounter with Naples and its theatrical tradition. Young (twenty-four years old), enthusiastic about his newly launched career, charged by his recent Roman success (Zoraide, January 1822), and true to Mayr’s quality writing and to the prestige that derived from it, Donizetti adapted to Naples’s theatre with the inborn skill of an acrobat and immediately met with success (52 performances from May to October 1822), beginning that process of empathy with Naples that would tie him to that city until 1838. La Zingara was written for the Teatro Nuovo sopra Toledo, which staged mainly comic works – both lyrical and in prose. When it opened, in 1724, it was a dialectal theatre; at Donizetti’s time, the Neapolitan dialect was confined to certain parts - music numbers and dialogues - entrusted to the buffo napoletano. The tradition of this comic role was carried on by the Casaccia family, active since 1749 and then at the third and fourth generations, with Carlo (in La Zingara Papaccione, the prison warder who is made a fool of by the gypsy) and his son Raffaele, who had just begun acting small parts (here that of the servant Sguiglio). The contact with these comic singers was Donizetti’s first and most direct way of absorbing the spirit of Naples: he trusted in their involvement with the audience and adapted to their creative and mimic exuberance, to their quips. The libretto by Andrea Leone Tottola conforms to the genre called “opera a peripezia”, which is to say an opera full of turns of events; this genre had reached such proportions, such complexity of different themes L 11 courteous message, provoking enigmatic reactions; and the beautiful love-sick girl (Ines, soprano) who is to marry someone she doesn’t love. Help is urgently needed. Enter Argilla (mezzo), who introduces herself with a bewitching cavatina (“Donzelle! a penetrar / l’arcan del vostro cor”) (No. 2). She sings a duet with the buffo Papaccione (No.3), seducing the simpleton with winking female arts that anticipate the sparkling duet between Dulcamara and Adina in Elisir d’Amore and a theme of the duet between Dulcamara and Nemorino (stretta); witnesses, undetected, the “Aria delle catene” (No.4) of the prisoner Sebastiano (bass), a scene typical of Baroque theatre, here enhanced with doleful and passionate lyricism. Lovers, prisoner and potentates’ intrigues carry the imprint of serious opera. The gypsy has a trait-d’union function with the serio-comic parts. She shows up before Fernando (tenor) after his Cavatina (No.5) and sings a Trio with him and his servant Sguiglio; she overhears the scheming of Don Ranuccio Zappador (bass) against the awaited guest, the Duke of Alziras (Aria: “Ecco un pugnal, su celalo”, No. 6); she concerts the First-Act Finale (No.7), where the characters sing a Sextet, in pairs, that turns from charming (the lovers), to parodistic (the courting of servant and nurse in countermelody), to sparkling (Argilla’s furtive preparations of charms, and Papaccione); and when her guile is about to be discovered by Ines’s angry nurse, the Duke and his retinue arrive and the gypsy rises wonderfully to the occasion with her long and courteous “Se un cor magnanimo tu chiudi in petto / (…) / La gioia, il giubilo ti siede a lato…”. Act Two opens with a Duet of conflict and love between the two lovers (No.8). Enter the gypsy, for the Chorus and Aria of Papaccione who lowers himself into the cistern (No.9): this descent to the infer- nals and chorus of spirits, dear to Baroque opera and parodied by opera buffa, originated from a brief cue of Caigniez and was developed into the buffo’s terror scenes and the underground chorus, in a sort of parody of Dante. The Septet (No.10) finds the characters in a situation of uncertainty: the crime has been foiled, the prisoner has disappeared and evil Don Ranuccio is confused; for a moment Donizetti sets the wit aside and digs deep into the feelings, with a wise and light hand, using an intensely lyrical melody. This was the most admired passage of all, and it is said that Bellini, who was then a pupil at the Collegio di San Sebastiano, studied and played it every day. The opera continues with the dramatic Aria of Ines (no number) - the love-sick girl contrasted by her father; then with the Trio “Miralo, è il tuo germano” (No. 11), where the generous Fernando is recognised as the Duke’s saviour and Don Ranuccio’s plot is revealed. This is the moment of truth, in prose. The gypsy, who has seen to the happy conclusion of all plights, is ready for applause. But a last surprise is in store: she is recognised as the daughter of the noble prisoner she has freed and ends the opera as the central character she is, with a recitativo d’affetti and a Rondò brillante (No.12) that delivers happiness to everyone. Franca Cella (Translated by Daniela Pilarz) 12 Massimiliano Barbolini (Fernando), Rosita Ramini (Ines) traute sich ihrer augenzwinkernden Komplizität mit dem Publikum an, machte sich das Aufzüngeln ihrer Einfälle und Mimik in der Unmittelbarkeit der raschen, bissigen Ausdrucksweise zu eigen. Andrea Leone Tottolas Libretto entsprach dem Geschmack für die Oper voller Wechselfälle des Schicksals, die an Themen und Intrigen so maßlos geworden war, daß sie - wie hier - in ihrer Vielfalt nach einer Originalvorlage zusammengefaßt wurde (La petite bohémienne, dreiaktiges Melodram von Louis Charles Caigniez, Paris, 1816). Wenn es um die zwei Buffos geht, versieht Tottola den Text mit neapolitanischen Farben. Den vielen Wechselfällen entnimmt er die für die Musik bestimmten Episoden (12 Nummern) und verleiht ihnen eine jeweils ernste oder heitere opernmäßige Identifizierung. Er erfaßt die Figur und magnetische Rolle der Zigeunerin Argilla. Dieses beherrschende, brillante und schlaue Figürchen treibt sich in einem Schloß herum, das sich festlich auf die angekündigte Ankunft des Vizekönigs vorbereitet; unter dem Vorwand der Wahrsagerei entdeckt sie die Geheimnisse aller und entwirrt sie. Sie vereint das in Schwierigkeiten befindliche junge Liebespaar, vereitelt das vom Schloßherrn gegen den Vizekönig angezettelte Verbrechen und entlarvt den gedungenen Mörder; sie entdeckt im unterirdischen Gewölbe einen adeligen Gefangenen, und um ihn zu befreien, haut sie den Kerkermeister übers Ohr, indem sie einen Abstieg in die Unterwelt (nämlich in die Zisterne) auf der Suche nach einem Schatz vortäuscht. Am Schluß entdeckt die großzügige Auflöserin der pièce à sauvetage, daß sie die als Kind verlorengegangene Tochter des adeligen Gefangenen ist. Donizetti verleiht ihr einen neuartigen Atem und macht ein zauberhaftes, geheimnisvolles Geschöpf in seinem eigenen Stil aus ihr. Sie lebt im magischen Halbschatten zwischen Lächeln und Verlockung und Geheimnis von Donizettis Zigeunermädchen a Zingara (Neapel, 12. Mai 1822) ist die erste Oper, die Gaetano Donizetti für diese Stadt und ihre Bühne schrieb. Jung (vierundzwanzig Jahre), voller Freude über die seit kurzem begonnene Laufbahn und durch den soeben in Rom (Zoraide, Januar 1822) erzielten Erfolg beschwingt, der Schreibqualtät seines Lehrers Mayr und dem daraus folgenden Ansehen treu, stürzt sich Donizetti mit der instinktiven Geschicklichkeit eines Menschen, der auf ein galoppierendes Pferd aufspringt, in das neapolitanische Musikleben. Er trifft sofort ins Schwarze (52 Vorstellungen zwischen Mai und Oktober 1922) und beginnt den Identifikationsprozeß mit der Stadt, der den Komponisten aus Bergamo bis 1838 an Neapel binden sollte. Die Oper wurde für das vorwiegend dem Bufforepertoire (einschließlich Sprechtheater) gewidmete Teatro Nuovo sopra Toledo geschrieben. Als das Haus 1724 eröffnet wurde, wurde dort neapolitanisch gesprochen. Zu Donizettis Zeiten war der Dialekt auf die Partien beschränkt, deren ausgeprägt neapolitanischer Charakter zu der Figur des neapolitanischen Buffos gehörte, ob Musiknummern oder gesprochene Dialoge. Beim Eintreffen Donizettis war die Tradition des neapolitanischen Buffos in Händen der seit 1749 tätigen Familie Casaccia, die bereits in der dritten und vierten Generation spielte. In der Zingara war Carlo Casaccia Papaccione, der Gefängniswärter, der sich hinters Licht führen läßt, und sein seit kurzem in Kleinrollen auftretender Sohn Raffaele der Diener Sguiglio. Der Kontakt mit den Buffosängern war der erste direkte Draht Donizettis zum typisch neapolitanischen Charakter, und er ver- L 14 Zigeunerwahrsagerei, mit dem Blick nach rückwärts auf Paisiellos Zigeunerinnen (I zingari in fiera auf ein Libretto von F. Cerlone ist von 1789) und nach vorne für den Zeitgeist offen, der die Suche nach dem spanischen, zigeunerhaften Element anregt: von den Balladen Berchets und Carrers über Manzonis Roman bis zu Verdi. Die Figur der Zigeunerin wird auch musikalisch zum Bindeglied einer Struktur mit durch gesprochene Dialoge getrennten Musiknummern. Sie hat ihren Auftritt nach dem einleitenden Chor und Szene (Nr. 1): Festliche Vorbereitungen auf dem Schloß, liebenswürdige Botschaft des erwarteten Gastes, die geheimnisvolle Reaktionen bewirkt, und ein schönes, unglückliches Mädchen (Sopran). Hilfe tut not. Die Zigeunerin (Mezzosopran) präsentiert sich mit der bezaubernden Kavatine “Donzelle! a penetrar / l’arcan del vostro cor” (Nr. 2). Sie singt das Duett mit dem Buffo Pappaccione (Nr. 3), wobei sie den Tölpel mit einer lächelnden Weiblichkeit lockt, die bereits auf das funkelnde Duett Dulcamara-Adina im Liebestrank verweist und auch ein Thema des Duetts Dulcamara-Nemorino (Stretta) aus der selben Oper enthält. Ungesehen hört sie die Arie (Nr. 4) des in Ketten liegenden Gefangenen Sebastiano (Baß), eine für das Barocktheater typische Szene, die hier mit schmerzlicher, leidenschaftlicher Kantabilität erneuert wird. Die Formen der opera seria gehören den Verliebten, Gefangenen und Ränkespielen der Mächtigen, während es Aufgabe der Zigeunerin ist, sie mit dem Genre der semiseria zu verbinden. Sie nähert sich Fernando (Tenor) nach dessen Kavatine (Nr. 5) und singt mit ihm und dem Diener Sguiglio ein kleines Terzett. Ungesehen hört sie die verschwörerischen Pläne von Don Ranuccio Zappador (Baß) gegen den Herzog von Alziras, den erwarteten Gast: Arie “Ecco un pugnal, su celalo” (Nr. 6). Der erste Akt endet mit einem Ensemble (Nr. 7) in Form eines Sextetts, in dem sich die Personen der Handlung paarweise wie verzaubert (die Verliebten), parodiert (im hofierenden Gegensang von Diener und Amme) und sprühend in ihren heimlichen Vorbereitungen für Zauberkunststücke (Argilla zu Papaccione) ausdrücken. Als die List von der erzürnten Amme gerade entdeckt wird, trifft der Herzog mit seinem Gefolge ein, und das Zigeunermädchen weiß dem Anlaß mit einer langen Phrase und Reverenz zu entsprechen: “Se un cor magnanimo tu chiudi in petto / (...) / La gioia, il giubilo ti siede a lato...”. Der zweite Akt beginnt mit einem Streit- und Versöhnungsduett der Verliebten (Nr. 8). Die Zigeunerin erscheint für Chor und Arie des Papaccione, der in die Zisterne hinabsteigt (Nr. 9). Die Szene des Abstiegs in die Unterwelt und Chors der Geister war der Barockoper lieb und wurde in der Buffooper parodiert; hier entspringt sie einer kurzen Anregung bei Caigniez, die Gelegenheit für die Angstausbrüche des Buffos und einen unterirdischen Chor gibt, der Dante parodiert. Das Septett (Nr. 10) überrascht die Figuren nach dem vereitelten Verbrechen, dem heimlich verschwundenen Gefangenen und dem verwirrten Schurken in einer Situation der Unsicherheit. Donizetti vergißt hier die Zerbrechlichkeit der Buffooper und geht mit leichter, kluger Hand und einer sich intensiv den Weg bahnenden Melodie in die Tiefe. Dieses war das meistbewunderte Stück; es wird erzählt, daß Bellini, der damals Schüler des Collegio San Sebastiano war, es täglich studierte und spielte. Der musikalische Aufbau setzt sich mit der dramatischen (unnumerierten) Arie der Ines, des verliebten Mädchens, das den Vater gegen sich hat, fort. Es folgt das Terzett “Miralo, è il tuo germano” (Nr. 11), in dem der großherzige Fernando als Retter erkannt und die Ränke Zappadors entdeckt 15 werden. Der Augenblick der (gesprochenen) Abrechnung ist gekommen. Die kleine Zigeunerin, die alles zu einem guten Ende gebracht hat, nimmt den Applaus entgegen. In dem adeligen Gefangenen, den sie gerettet hat, findet sie den Vater wieder und beherrscht den Schluß der Oper mit einem recitativo d’affetti und brillanten Rondo (Nr. 12), das allen Glück und Freude spendet. Franca Cella (Übersetzung: Eva Pleus) 16 Le livret d’Andrea Leone Tottola répond au style de l’opéra à péripéties, d’une richesse démesurée en matière de thèmes et d’intrigues et, comme ici, résumé dans sa multiplicité par un modèle original (La petite bohémienne, mélodrame en 3 actes en prose de Louis Charles Caigniez, représenté à Paris en 1816). Tottola traduit en caractère napolitain quand le discours est confié aux deux bouffes et choisit les épisodes destinés à la musique (12 numéros) parmi les nombreuses péripéties, les poussant vers une identification lyrique, seria ou giocosa. Il croque le personnage et le rôle entraînant de la Bohémienne Argilla : figure dominatrice, brillante et habile, elle rôde dans un château en fête pour la prochaine visite du Vice-roi et, sous prétexte de prédire l’avenir, dévoile les secrets de chacun et les débrouille. Elle unit le couple d’amoureux en difficulté, évente l’assassinat du Vice-roi ourdi par le seigneur des lieux et démasque le sicaire, découvre dans les souterrains un noble prisonnier et, pour le délivrer, embobine le geôlier en organisant une descente aux enfers dans la citerne à la recherche d’un trésor. A la fin, la généreuse bienfaitrice de la “pièce à sauvetage ” découvre qu’elle est la fille du noble prisonnier. Donizetti lui donne une ampleur nouvelle, faisant d’elle une charmante et mystérieuse créature donizettienne vivant dans une pénombre magique faite de sourire et de prédiction vagabonde, le regard tourné à la fois vers les Bohémiennes de Paisiello (I zingari in fiera, 1789, sur un livret de F. Cerlone) et vers l’esprit des temps qui incite à faire appel à l’élément espagnol et bohémien, des ballades de Berchet ou de Carrer au roman de Manzoni, ou encore à Verdi. Le personnage de la Bohémienne devient aussi, au plan musical, l’élément liant et unificateur d’une structure dans laquelle les numéros musicaux sont entre- Séduction et mystère de la Bohémienne de Donizetti a Zingara (Naples, 12 mai 1822) est le premier rendez-vous lyrique de Gaetano Donizetti avec la ville et le théâtre napolitain. Jeune (vingtquatre ans), heureux d’avoir entrepris cette carrière et encore empreint du succès obtenu à Rome avec Zoraide, en janvier 1822, fidèle à l’écriture de qualité de son maître Mayr et au prestige qui en découle, Donizetti se jette dans le monde théâtral napolitain avec la dextérité instinctive de ceux qui sautent sur un cheval lancé au galop. Et il fait mouche immédiatement, avec 52 représentations entre mai et octobre 1822, amorçant ainsi le processus d’identification avec la ville qui unira le compositeur à Naples jusqu’en 1838. L’œuvre est écrite pour le Teatro Nuovo sopra Toledo, voué en grande partie au répertoire bouffe, y compris en prose. On y parle en dialecte napolitain dès son inauguration en 1724 ; on le parle encore au temps de Donizetti, dans les parties où le caractère purement napolitain est l’apanage du bouffe napolitain : numéros musicaux entrecoupés de récitatifs. Quand Donizetti arrive, la tradition du bouffe napolitain est liée à la famille Casaccia, implantée depuis 1749 et parvenue aux troisième et quatrième générations avec Carlo, interprète dans La Zingara de Papaccione, le geôlier qui se laisse berner, et son fils Raffaele, lancé depuis peu dans de petits rôles, qui interprète le serviteur Sguiglio. Le contact avec les chanteurs bouffes est le premier lien entre Donizetti et le caractère napolitain : il s’en remet à leur complicité avec le public, entre dans leur créativité et leurs mimiques pétillantes comme dans la spontanéité de leur langage vif et salace. L 18 Le deuxième acte débute par un duo de contraste et d’amour entre les deux amoureux (n° 8). Survient la Bohémienne pour le Chœur et l’Aria de Papaccione qui amorce sa descente dans la citerne (n° 9) : la scène de la Descente aux Enfers avec Chœur d’Esprits, si chère à l’opéra baroque et parodiée dans l’opera buffa, se développe sur une idée de Caigniez qui donne lieu aux scènes de peur du bouffe et au Chœur souterrain, dans une parodie dantesque. Le Septuor (n° 10) surprend les personnages dans une situation d’incertitude en suspens, après l’assassinat éventé, le prisonnier mystérieusement disparu, le méchant embarrassé ; Donizetti oublie la fragilité de l’opera buffa et touche en profondeur, d’une main à la fois légère et savante, avec un rythme intense dans la mélodie qui s’annonce. Ce passage fut le plus admiré et l’on raconte que Bellini, alors élève du Collège de San Sebastiano, l’étudiait et le jouait chaque jour. La structure musicale continue avec l’Aria dramatique d’Ines (sans numéro), la jeune fille dont le père contrarie les amours, puis avec le Terzetto “Miralo, è il tuo germano” (n° 11), où le généreux Fernando est enfin reconnu comme un sauveur et le complot de Zappador éventé. C’est le moment des règlements de compte, en prose. La Bohémienne, qui a mené à bien toutes ces affaires, apparaît pour les applaudissements. Elle découvre que le noble prisonnier qu’elle a libéré est en fait son père et conclut l’opéra en dominatrice, avec un récitatif d’affetti et un brillant Rondò (n° 12) qui dispense du bonheur à tous. coupés de récitatifs. Elle fait son apparition après le Chœur et la scène d’introduction (n° 1) : préparatifs de fête au château, message courtois de l’hôte attendu qui suscite des réactions énigmatiques, et apparition d’une belle jeune fille malheureuse (soprano). Un besoin d’aide se fait cruellement sentir. Arrivée de la Bohémienne (mezzo-soprano) avec la Cavatine enjôleuse (“Donzelle ! a penetrar / l’arcan del vostro cor”) (n° 2). Elle chante le Duo avec le bouffe Papaccione (n° 3) en appâtant le benêt avec une féminité souriante qui devance le pétillant Duo entre Dulcamara et Adina dans l’Elixir d’amour, et anticipe un thème du Duo entre Dulcamara et Nemorino (stretta). Elle assiste sans être vue à l’Aria avec les chaînes (n° 4) du prisonnier Sebastiano (basse), scène typique du théâtre baroque renouvelée avec une cantabilité douloureuse et passionnée. Amoureux, prisonniers et machinations des puissants apportent les formes de l’opera seria ; à la Bohémienne de les relier au genre semiserio. Elle s’approche de Fernando (ténor) après sa Cavatine (n° 5) et entame un terzetto avec lui et le serviteur Sguiglio. Elle assiste, sans être vue, aux projets de complot de Don Ranuccio Zappador (basse) contre le Duc d’Alziras, l’hôte attendu : aria “Ecco un pugnal, su celalo” (n° 6). Elle concerte le Finale (n° 7) du premier acte dans lequel les personnages, par couples, égrènent un sextuor enchanté (les amoureux), parodié (le contre-chant de la cour entre le serviteur et la nourrice), bondissant de furtifs préparatifs de charme (Argilla à Papaccione). Et quand la duperie est sur le point d’être dévoilée par la nourrice en colère, voilà que se présente le cortège du Duc et la Bohémienne se reconvertit admirablement par une longue phrase et une profonde révérence : “Se un cor magnanimo tu chiudi in petto / (…) / La gioia, il giubilo ti siede a lato…”. Franca Cella (Traduit par Cécile Viars) 19 ferito dal re. Argilla, nascosta, sente tutto e decide di sventare il piano. Fernando ed Ines, coll’aiuto della zingara, finalmente possono riabbracciarsi; ma Amelia li sorprende e trascina via la povera Ines. Il primo atto si conclude con l’arrivo del Duca d’Alziras. TRAMA ATTO PRIMO L’azione si svolge in Spagna nel castello di Don Ranuccio Zappador, dove c’è gran trambusto per la prossima visita del Duca d’Alziras, ministro del re. Don Ranuccio informa sua figlia Ines di aver scelto per lei lo sposo, Antonio Alvarez, ma ella confida alla nutrice Amelia di essere innamorata di un giovane di nome Fernando, che ha incontrato durante un soggiorno in montagna. Amelia la mette in guardia contro una tale passione, che non si addice ad una ragazza del suo rango e che scatenerà le ire del padre. Giunge al castello la zingara Argilla, con altre zingare al seguito. Scaltramente adesca il buffo Papaccione, servo di Don Ranuccio e scopre che è il guardiano della prigione, in cui è custodito un misterioso prigioniero. Papaccione viene richiamato dal padrone e Argilla ne approfitta per cercare di scoprirne di più: avvicinatasi alla prigione raccoglie un biglietto di richiesta d’aiuto scritto proprio dal malcapitato prigioniero, a cui promette salvezza. Con la scusa di aver saputo dagli astri che nel castello si custodisce un tesoro, Argilla si fa condurre da Papaccione al cospetto del prigioniero e scopre così che si tratta di Don Sebastiano Alvarez, zio di Antonio. Nel frattempo giunge al castello anche Fernando, con il suo servo Sguiglio. Argilla, che ha sentito Ines sospirare per lui, decide di aiutare il giovane ad incontrare l’amata. Don Ranuccio, intanto, rivela ad Antonio le sue trame: ha imprigionato suo zio Sebastiano e si è impossessato dei suoi beni perché il giovane possa, sposando Ines, entrarne a sua volta in possesso; in cambio però lui dovrà uccidere il Duca d’Alziras, del quale Don Ranuccio vuole vendicarsi per essergli stato pre- ATTO SECONDO E’ quasi notte e Fernando cerca Argilla perché lo aiuti ad introdursi nuovamente nel castello; in quel mentre arriva Ines e i due giovani possono nuovamente riabbracciarsi. Ines è convinta che Fernando nasconda un segreto poiché non le rivela la sua identità, ma il giovane la rassicura che a tempo debito le svelerà ogni cosa. I due si lasciano ed Argilla racconta a Fernando il piano malvagio di Don Ranuccio: Fernando dovrà fermare Antonio e sventare l’assassinio del Duca. Poi la scaltra zingara si appresta a liberare Don Sebastiano: racconta a Papaccione che gli astri le hanno rivelato dove si trova il tesoro e che Plutone lo ha prescelto per impossessarsene. Si fa consegnare le chiavi della prigione (perché Plutone non vuole altri metalli nella cava del tesoro) e lo fa scendere in una cisterna, dove Sguiglio e altri zingari sono pronti ad accoglierlo a legnate. Mentre tutto questo avviene, indisturbata, libera Don Sebastiano. Don Ranuccio ed Antonio si accingono a dare inizio al loro losco progetto: Antonio penetra nelle stanze del Duca ma trova Fernando che lo ferma; allora scappa, inseguito da Fernando e dal Duca stesso. Don Ranuccio si mostra attonito alla notizia di un traditore nel suo castello, ma ecco comparire il liberato Don Sebastiano, che si fa riconoscere dal Duca di Alziras. Quest’ultimo gli rivela che una sola persona potrebbe volergli tanto male da tentare di ucciderlo: suo fratello, che tanti anni addietro egli ha scacciato credendolo ingiustamente un traditore e verso il 20 quale ora prova rimorso. Don Sebastiano, sentendo ciò, gli presenta il suo salvatore, Fernando, che è proprio suo fratello! Ecco svelato perché Fernando manteneva segreta la sua identità. I due fratelli si riappacificano e la verità viene a galla: Argilla racconta che Don Ranuccio voleva assassinare il Duca per mano di Antonio; questi viene riconosciuto da Don Sebastiano come suo nipote. Il Duca e Don Sebastiano vorrebbero condannare Don Ranuccio, ma dato che è il padre di Ines, la giovane amata da Fernando, gli concedono di vivere segregato nel suo castello. Tutto sembra ormai felicemente concluso, quando Argilla rivela agli astanti di essere di nobile nascita: rapita da bambina ella è alla ricerca della sua famiglia, di cui conserva solo un ciondolo che aveva al collo al momento del rapimento. Attonito, Don Sebastiano riconosce quell’oggetto: Argilla è sua figlia ed ora finalmente i due si possono riabbracciare. SYNOPSIS ACT ONE The action takes pace in Spain, in the castle of Don Ranuccio Zappador. While everybody is busy preparing for the visit of the Viceroy, the Duke of Alziras, the castle’s master informs his daughter Ines that he has chosen a husband for her in the person of Antonio Alvarez. Ines, however, confides to her nurse Amelia that she is in love with Fernando, a young man met during her stay in the mountains. Amelia warns her: he does not suit a girl of her status and she will provoke her father’s wrath. The gypsy girl Argilla, in the meanwhile, has arrived at the castle with her retinue of friends. With cunning arts she seduces the gullible Papaccione, Don Ranuccio’s servant, and discovers that he is the warder of the castle’s dungeons, where a mysterious prisoner is kept. When Papaccione is summoned by his master, Argilla is left alone and tries to find out more about it: she wanders to the prison’s wall and, having found a message dropped by the wretched captive, in which he pleads for help, she promises to come to his rescue. Pretending the stars have revealed to her that a treasure is hidden in the castle, Argilla beguiles Papaccione into taking her to the prisoner and learns that he is Don Sebastiano Alvarez, Antonio’s uncle. In the meantime also Fernando and his servant Sguiglio have arrived in sight of the castle. Argilla, who has overheard Ines’s sighs of love, decides to help them steal inside so that the couple can meet. Don Ranuccio, meanwhile, informs Antonio of his wicked plan: he has imprisoned his uncle Sebastiano and taken hold of his fortune so that, marrying Ines, Antonio may in turn come into its possession; in 21 exchange, however, the young man must kill the Duke of Alziras and thus avenge Don Ranuccio, for for the Duke was elected by the king to the position of Viceroy in his place. Argilla, undetected, overhears him and decides to foil the plot. Fernando and Ines, with the gypsy’s help, can finally see each other again; but Amelia catches them and drags Ines away. The act ends with the arrival of the Duke of Alziras. fronted by the freed Don Sebastiano, who makes himself known and is recognised by the Duke of Alziras. This reveals that only one person would have reason to kill him: his brother, whom he unjustly drove away many years before believing him a traitor, for which he now feels remorseful. Hearing this Don Sebastiano introduces the Duke’s saviour: it is his brother Fernando! This explains why Fernando kept his identity secret. The two brothers make peace and the truth begins to emerge: Argilla reveals Don Ranuccio’s assassination plot and Antonio is recognised as Don Sebastiano’s nephew. The Duke and Don Sebastiano would want Don Ranuccio convicted, but since he is the father of Ines, Fernando’s beloved, they accept that he may spend the rest of his life segregated inside his castle. All seems to have come to a happy conclusion, but a last surprise is in store: Argilla reveals that she is of noble birth. Kidnapped as a child, she is looking for her family; she has a pendant, which she was wearing at the moment of her abduction. Astonished, Don Sebastiano recognises it: the gypsy is her lost daughter and the two are finally reunited. ACT TWO Night is falling and Fernando is looking for Argilla because he wants her help again to get inside the castle; unexpectedly, Ines shows up and the two lovers can spend some more time together. Ines doubts Fernando’s sincerity because he does not want to reveal his identity, but the young man reassures her that at the right time he will tell her everything. The lovers part and Argilla informs Fernando about Don Ranuccio’s evil plot: the youth must stop Antonio and thwart the Duke’s assassination. Then the clever gypsy prepares to carry out her own plan to free Don Sebastiano: she tells Papaccione that the stars have revealed where the treasure is hidden and that Pluto has indicated him as the chosen one who is to retrieve it. She tricks him into giving her the dungeons’ key (because Pluto wants no other metal into the treasure’s chamber) and makes him lower himself into a cistern, where Sguiglio and other gypsies lie in waiting armed with sticks. Then, undisturbed, she frees Don Sebastiano. While this is going on Don Ranuccio and Antonio set out on their sinister project: Antonio introduces himself into the Duke’s apartments but finds Fernando, who stops him; he flees, pursued by Fernando and the Duke himself. At the news that there is a traitor in his castle Don Ranuccio fakes surprise, but is con22 Antonios Onkel Sebastiano eingekerkert und sich dessen Güter bemächtigt, damit der junge Mann durch die Heirat mit Ines seinerseits in deren Besitz gelange. Im Gegenzug muß dieser aber den Herzog von Alziras töten, an dem sich Don Ranuccio rächen will, weil er ihm vom König vorgezogen wurde. Argilla hört im Verborgenen alles und beschließt, den Plan zu vereiteln. Fernando und Ines können einander mit ihrer Hilfe endlich wieder in die Arme sinken, doch werden sie von Amelia überrascht, die die arme Ines wegzerrt. Der erste Akt endet mit dem Eintreffen des Herzogs von Alziras. DIE HANDLUNG ERSTER AKT Die Handlung spielt in Spanien im Schloß von Don Ranuccio Zappador, wo wegen des kommenden Besuchs des Herzogs von Alziras, einem Minister des Königs, ein großes Durcheinander herrscht. Don Ranuccio teilt seiner Tochter Ines mit, daß er für sie Antonio Alvarez als Gemahl ausgesucht hat. Ines vertraut ihrer Amme Amelia aber an, daß sie einen Jüngling namens Fernando liebt, den sie bei einem Aufenthalt in den Bergen kennengelernt hat. Amelia warnt sie vor einer solchen Leidenschaft, die sich für ein Mädchen ihres Ranges nicht ziemt und den Zorn ihres Vaters hervorrufen wird. Die Zigeunerin Argilla kommt, mit weiteren Zigeunerinnen im Gefolge, ins Schloß. Sie lockt auf schlaue Weise den komischen Papaccione, Diener von Don Ranuccio, an und entdeckt, daß er der Aufseher des Kerkers ist, in dem ein geheimnisvoller Gefangener verwahrt wird. Papaccione wird von seinem Herrn gerufen, was Argilla nutzt, um mehr herauszubekommen. Nachdem sie sich dem Kerker genähert hat, findet sie eine von dem unglückseligen Gefangenen geschriebene Botschaft mit der Bitte um Hilfe und verspricht, ihn zu retten. Unter dem Vorwand, sie habe in den Sternen gelesen, daß sich im Schloß ein Schatz befindet, läßt sich Argilla von Papaccione zu dem Gefangenen bringen und entdeckt auf diese Weise, daß e s sich um Don Sebastiano Alvarez, den Onkel Antonios, handelt. Inzwischen kommt auch Fernando mit seinem Diener Sguiglio zum Schloß. Argilla, die hörte, wie Ines nach ihm schmachtete, beschließt, dem Jüngling zu helfen, damit er die Geliebte sehen kann. Inzwischen entdeckt Don Ranuccio Antonio seine Intrigen: Er hat ZWEITER AKT Es ist fast Nacht. Fernando sucht nach Argilla, damit sie ihm hilft, neuerlich in das Schloß hineinzukommen. Da kommt Ines, und die jungen Leute können einander wieder in die Arme fallen. Ines ist davon überzeugt, daß ihr Fernando etwas verbirgt, weil er ihr seine Identität verheimlicht, aber der Jüngling beruhigt sie, daß er ihr zur richtigen Zeit alles entdecken wird. Als Ines geht, erzählt Argilla Fernando den bösen Plan von Don Ranuccio; Fernando soll Antonio zurückhalten und die Ermordung des Herzogs vereiteln. Dann macht sich die schlaue Zigeunerin zur Befreiung Don Sebastianos bereit. Sie erzählt Papaccione, daß ihr die Sterne gezeigt hätten, wo sich der Schatz befindet und er von Pluto dazu auserwählt wurde, in seinen Besitz zu gelangen. Sie läßt sich die Schlüssel zum Kerker aushändigen (weil Pluto in der Schatzhöhle kein anderes Metall wünscht) und läßt ihn in eine Zisterne hinabsteigen, in der sich Sguiglio und andere Zigeuner befinden, die darauf warten, ihn mit Hieben zu empfangen. Während dieser Ereignisse befreit sie ungestört Don Sebastiano. 23 Don Ranuccio und Antonio schicken sich an, ihren finsteren Plan auszuführen. Antonio dringt in die Gemächer des Herzogs ein, stößt aber auf Fernando, der ihm in den Arm fällt. Er flüchtet, von Fernando und dem Herzog selbst verfolgt. Don Ranuccio zeigt sich auf die Nachricht von einem in seinem Schloß befindlichen Verräter hin entsetzt, doch nun erscheint der befreite Don Sebastiano, der sich dem Herzog von Alziras zu erkennen gibt. Dieser entdeckt ihm, daß ihn nur ein Mensch so hassen kann, um ihn ermorden zu wollen, nämlich sein Bruder, den er vor vielen Jahren fortgejagt hat, weil er ihn ungerechterweise für einen Verräter hielt, weshalb er jetzt unter Gewissensbissen leidet. Als Don Sebastiano dies hört, stellt er ihm Fernando, seinen Retter, vor - und der ist sein Bruder! Nun wird klar, warum Fernando seine Identität geheimhielt. Die Brüder schließen Frieden, und die Wahrheit kommt ans Licht, denn Argilla erzählt, daß Don Ranuccio den Herzog von Antonio, in welchem Don Sebastiano seinen Neffen erkennt, töten lassen wollte. Der Herzog und Don Sebastiano würden Don Rannucio gerne verurteilen, aber weil er der Vater der von Fernando geliebten Ines ist, wird ihm zugestanden, abgeschieden in seinem Schloß zu leben. Alles scheint bereits ein glückliches Ende gefunden zu haben; da entdeckt Argilla den Anwesenden, daß sie von adeliger Geburt ist. Als Kind geraubt, ist sie auf der Suche nach ihrer Familie, von der sie nur ein Kettchen bewahrt, das sie um den Hals trug, als sie geraubt wurde. Don Sebastiano erkennt dieses fassungslos: Argilla ist seine Tochter, und die beiden sehen einander endlich wieder. TRAME ACTE I La scène se déroule en Espagne, dans le palais de Don Ranuccio Zappador, où règne une grande animation en raison de la prochaine visite du Duc d’Alziras, ministre du roi. Don Ranuccio informe sa fille Ines qu’il lui a choisi comme époux Antonio Alvarez, mais elle confie à sa nourrice Amelia qu’elle est éprise du jeune Fernando, qu’elle a connu lors d’un séjour à la montagne. Amelia la met en garde contre une telle passion, qui ne sied pas à une jeune fille de son rang et qui suscitera la colère de son père. Surviennent au château Argilla et d’autres jeunes filles, toutes Bohémiennes. Avec adresse, elle séduit le bouffe Papaccione, serviteur de Don Ranuccio, et découvre qu’il est le geôlier de la prison dans laquelle est enfermé un mystérieux prisonnier. Papaccione est appelé par son maître et Argilla en profite pour tenter de percer le mystère : s’étant approchée de la geôle, elle ramasse un billet dans lequel le prisonnier demande de l’aide ; elle lui promet alors de le délivrer. Ayant fait croire à Papaccione qu’elle a appris par les astres l’existence d’un trésor au château, Argilla se fait conduire auprès du prisonnier et découvre qu’il s’agit de Don Sebastiano Alvarez, oncle d’Antonio. Pendant ce temps, Fernand arrive lui aussi au château avec son serviteur Sguiglio. Argilla, qui a entendu Inès soupirer après lui, décide d’aider le jeune homme à rencontrer sa bien-aimée. Don Ranuccio révèle son plan à Antonio : il a emprisonné son oncle Sebastiano et confisqué ses biens pour que le jeune homme puisse, en épousant Ines, s’en emparer à son tour ; en échange, il devra tuer le Duc d’Alziras duquel Don Ranuccio veut se venger 24 pour avoir été préféré par le roi. Dans sa cachette, Argilla entend tout et décide d’éventer le complot. Fernando et Ines, aidé de la Bohémienne, peuvent enfin se retrouver mais Amelia les surprend et entraîne la pauvre Ines. Le premier acte se termine par l’arrivée du Duc d’Alziras. mais du remords. En entendant ces mots, Don Sebastiano lui présente son sauveur, en qui le Duc reconnaît son frère ! voilà la raison pour laquelle Fernando cachait sa véritable identité. Les deux frères s’embrassent et la vérité se fait jour : Argilla raconte que Don Ranuccio voulait faire assassiner le Duc par Antonio, mais Don Sebastiano reconnaît en lui son neveu. Le Duc et Don Sebastiano voudraient condamner Don Ranuccio, mais s’agissant du père d’Ines, la bien-aimée de Fernando, ils lui accordent de vivre reclus dans son château. C’est alors qu’Argilla révèle à l’assemblée qu’elle est de haute naissance : ayant été enlevée quand elle était enfant, elle est à la recherche de sa famille, dont elle conserve seulement un bijou qu’elle portait au cou lors de son enlèvement. Don Sebastiano reconnaît l’objet avec stupeur et déclare qu’Argilla est sa propre fille. Tous deux tombent dans les bras l’un de l’autre. ACTE II Il fait presque nuit et Fernando cherche Argilla pour qu’elle l’aide à s’introduire de nouveau dans le château ; survient Ines et les deux jeunes gens s’embrassent. Ines est convaincue que Fernando cache un secret parce qu’il ne lui révèle pas son identité, mais le jeune homme la rassure et lui affirme qu’elle saura tout en temps voulu. Tous deux se quittent et Argilla révèle à Fernando le complot de Don Ranuccio : Fernando doit retenir Antonio et empêcher l’assassinat du Duc. Puis l’habile Bohémienne s’apprête à libérer Don Sebastiano : elle raconte à Papaccione que les astres lui ont révélé la cachette du trésor et que Pluton l’a choisi pour s’en emparer. Le serviteur lui confie les clés de la prison (car Pluton ne veut pas d’autres métaux dans la pièce du trésor) et elle le fait descendre dans une citerne où Sguiglio et d’autres Bohémiens l’accueillent à coups de bâton. Pendant ce temps, Argilla libère Don Sebastiano. Don Ranuccio et Antonio s’apprêtent à exécuter leur plan : Antonio pénètre dans les appartements du Duc, mais y ayant trouvé Fernando qui l’attend, s’enfuit tandis que Fernando et le Duc tentent de le rattraper. Don Ranuccio se montre stupéfait à l’annonce qu’un traître se trouve dans son château, mais c’est alors que survient Don Sebastiano, que le Duc reconnaît. Celui-ci lui apprend qu’une seule personne pourrait lui en vouloir assez pour tenter de le tuer : son frère, qu’il avait chassé autrefois, le prenant injustement pour un traître et envers qui il éprouve désor25 Gaetano Donizetti LA ZINGARA Libretto by Andrea Leone Tottola Translated by Daniela Pilarz (©2002) Gaetano Donizetti LIBRETTO 1 - Preludio 1 - Prelude ATTO PRIMO ACT ONE Scena Prima Interno di antico castello. La sua gran porta è in mezzo. Da un lato magnifica scala, che conduce ad appartamenti superiori, e dall’altro avanzi di una Gotica architettura, nella base della quale è una bassa porta di ferro, che dà ingressoad un sotterraneo. I domestici di Ranuccio si affrettano ad ornare le mura del castello di fiori e di altri oggetti di festa; indi Ranuccio, ed Ines, infine Amelia, ed Antonio. Scene I The interior of an old castle. In the middle is the main entrance; on one side, a magnificent stairway leading to the upper apartments; on the other the remains of some Gothic structure, at the bottom of which a low iron gate gives admission to a dungeon. Ranuccio’s servants, busy decorating the castle’s walls with flowers and other ornaments; then Ranuccio, and Ines; finally Amelia, and Antonio. 2 Coro - Dell’ospite illustre L’arrivo si onori. Più in là quei festoni… Più in ordine quei fiori… (Dirigendo il lavoro e sollecitando gli altri domestici alla esecuzione) Trionfi fastosa Nel centro la rosa; Le cifre a due lati… Che flemma! Oh scempiati! Ben presto il lavoro Si dè terminar. In giorno sì lieto Ogni alma giuliva Far deve gli evviva All’etra echeggiar! 3 Ranuccio - (Ad Ines) Al piacer, che spira intorno, Deh risponda il tuo contento: Ah! per te più bel momento Forse appresta il dio d’amor. Ines - Sarò lieta, se a te piace, 2 Chorus - We must honour the arrival of our illustrious guest. Move those festoons further over… Arrange those flowers in a better way… (Directing the work and urging the other servants to execute his orders) Place that splendid rose in the middle; the monograms on both sides… What sluggishness! Oh, what fools! The preparations must soon be finished. And on such a joyful day every merry soul must make their cheers resound! 3 Ranuccio - (To Ines) Let your happiness add to the merry-making that is in the air: ah! Love may be preparing for you the sweetest of moments. Ines - I’ll be happy, if this pleases you, 27 Ma di amor non favellarmi: Io serbar vo’ quella pace, Che gustai tranquilla ognor. Ranuccio - Paga appien ti bramo, o figlia. Ines - (Ma non già col mio tesoro!) Ranuccio - Il tuo ben se ti consiglia, Non opporti al genitor. Ines - Ad amar chi mi consiglia Guerra impone a questo cor. Ranuccio - Ad ubbidirmi La figlia apprenda; A miei voleri Pronta si arrenda, O attenda il fulmine Del mio furor. Ines - Come all’istante Ti sei cangiato! Deh calma l’ira O padre amato, Ines non merita Tanto rigor. 4 Antonio/ Amelia (Dalla porta di prospetto con Amelia) Il Duca di Alziras spedito ha un espresso. E come ha promesso, con nobil corteggio quest’oggi egli stesso il nostro castello verrà ad onorar. Ranuccio - Che venga, l’attendo con sommo piacere. (Mie furie! V’intendo, nel sen voi fremete? Sì, paghe sarete, quell’empio cadrà). Ines - (Quest’alma dolente, but do not speak to me of love: I want to retain the peace that I have enjoyed so far. Ranuccio - I desire your happiness, my daughter. Ines - (But not with the man I love!) Ranuccio - Your father advises you for own good, you should not go against him. Ines - He that advises me to love declares war to my heart. Ranuccio - My daughter must learn to obey me; she must surrender promptly to my will, or else be ready for my wrath. Ines - How, in an instant, you have changed! Ah, calm your anger, beloved father, Ines does not deserve such rigour. 4 Antonio/ Amelia (From the front door with Amelia) The Duke of Alziras has sent a message. And as he promised, today he will arrive with his noble retinue and honour us with a visit to our castle. Ranuccio - Let him come, I await him with great pleasure. (Fury, I can feel you quiver in my breast! Yes you shall be appeased, that evil man shall fall). Ines - (This sorrowful soul, 28 confused, bewildered, feels no more joy, knows no more peace). Amelia/ Antonio/ Chorus - What a feast! What fun! What fine merry-making! Amid toasts and laughter we’ll have a sparkling time. 5 Ranuccio - Finally I shall meet again the Duke of Alziras. Let us then give him a grand welcome, such as is proper for a man of his renown. Antonio - All will meet your rightful expectations. Amelia - Ines, what is troubling you? Ines - Oh, Amelia, my father wants my unhappiness… Amelia - Come, my child, is it because of Antonio? Ines - What do you know about this? Amelia - He urged me to dispose you in favour of that young man. Ines - You’re wasting your time. Don’t you know that my heart is already bestowed? Amelia - Ah, stop thinking of that stranger! Woe would betide you and me if your father came to know about him! Ines - First of all he’s no stranger, he is Fernando. Amelia - Fernando! Ines - Yes. Why, isn’t that enough? Amelia - No, it isn’t: we need to examine his status, his birth, his social condition… and above all his virutes. Ines - These things are not written in the code of Love. Amelia - Oh dear! What an expert my young lady has become! Ines - Amelia! (She leaves). confusa, smarrita, più gioia non sente, più pace non ha). Amelia/ Antonio/ Coro - Che feste! Che spasso! Che bell’allegria! Fra i brindisi, e ’l chiasso brillar si dovrà. 5 Ranuccio - Mi è dato alfine riabbracciare il Duca di Alziras. Sia dunque accolto con tutti gli onori del caso. Antonio - Tutto risponderà alle vostre premure. Amelia - Ines? Che avete? Ines - Oh Amelia, il padre vuol rendermi infelice… Amelia - Oh su bambina, sarà forse... Antonio? Ines - Ma che sai tu di ciò? Amelia - Mi ha egli premurato a disporvi a vantaggio di quel giovane. Ines - Vi perdi il tempo. Ignori tu, che il mio cuore sia di già prevenuto? Amelia - Ah, non penserete forse a quello sconosciuto! guai a voi, ed a me, se vostro padre lo venisse a sapere! Ines - Prima cosa non è uno sconosciuto,è Fernando. Amelia - Fernando! Ines - Sì, perchè, non basta? Amelia - No non basta: conviene conoscere il suo stato, i suoi natali, la sua condizione… e soprattutto le sue virtù. Ines - Queste cose non appartengono al codice dell’ Amore. Amelia - Oh! oh! Come si è fatta esperta la mia bella signorina! Ines - Oh, Amelia! (Via). 29 Scena II Dalla porta in fondo Argilla, indi Ghita, Manuelitta, ed altri Zingari. Scene II Argilla, then Ghita, Manuelitta and other gypsies, from the door in the back . 6 Argilla - Donzelle! A penetrar l’arcan del vostro cor; zerbini! A disvelar se fido è il vostro amor; quel fervido desir, che sospirar vi fa, oh vedove! A scovrir con tutta libertà; la zingara famosa, Argilla l’indovina: la donna portentosa per voi venuta è qua. Discende in ogni cor lo sguardo mio sicuro; e il velo del futuro, ombre per me non ha. Mariti!… Avvicinatevi, è il labbro mio discreto; sol vi dirò in segreto la vostra infedeltà. Mogli! Non dubitate, son femina di mondo; saprò d’oblio profondo coprir la verità. Su presto miei signori, se il ver saper volete, che piovano monete, ma d’oro, e in quantità. 7 Orsù Argilla, via per il palazzo, dove sono tutti in moto per l’arrivo del Duca di Alziras. Ecco Papaccione. La sua amicizia potrebbe giovarmi non poco. Sia sorpresa la sua credulità col brillante spaccio de’ miei già meditati indovini. 6 Argilla - Maidens! I’ll unravel the secrets of your hearts; young men! I’ll tell you whether your love is faithful; widows! I offer you the freedom to discover that ardent desire that makes you sigh; here is the famous gypsy, Argilla, the fortune teller: this prodigious woman is here for you. My searching eye looks deep in every heart; and the future holds no mysteries for me. Husbands!… Approach, my lips are discreet; your betrayals will be a secret between you and me. Wives! Have no doubts, I know the ways of the world; I will cover up the truth and let it fall into oblivion. Come, quick, ladies and gentlemen, if you want to know the truth, shower me with coins, but gold ones, and lots of them. 7 Come on, Argilla, into the palace, where everyone busy preparing for the arrival of the Duke. Here comes Papaccione. His friendship could be of great use to me. Let’s surprise his credulity with the brilliant pretence of my already-planned divining. 30 Scena III Papaccione dagli appartamenti, ed Argilla in ascolto. Scene III Papaccione, from the apartments, and Argilla, eavesdropping. 8 Papaccione - “Quid est homo sine femina?” No scolaro maliziuso a lo masto addimmaunò. E raspannose il caruso così il masto se spiegò. “Est carofanum sfronnato, Maccabeum sine connimmo, vuzzariellum senza rimmo, quod non sapit cammenà.” Lo sacc’io, che da qualch’anno faccio passo a la donnetta, non c’è cosa, che m’alletta, sempre friddo pe me fa. Argilla - (Oh briccone! Un poco aspetta, che a scaldarti io sono qua). (Presentandosi) Mio grazioso grassottello! Porgi un poco a me la mano, volgi l’occhio ladroncello, ch’io ti voglio indovinar. Papaccione (Oh che carne for’assisa! Che boccon del sommo Giove! Nuce vecchie, e nuce nove me potria mo affè scontà). Argilla - E così del tuo pianeta il destin saper non vuoi? Papaccione - Sto bedenno sta cometa, che m’ha fatto sorzetà. Argilla - Tu dei stato da ragazzo sempre intento al ceto basso: di cervel leggiero, e pazzo, niente studio, sempre spasso: e una certa Tommasina ti fe’ un giorno sospirar. 8 Papaccione - “What’s a man without a woman? Was the malicious question of a pupil to his teacher. And, scratching his bald head, the teacher answered: “He is an overblown flower, macaroni without sauce, a boat without oars, he cannot stand on his own legs. I, for one, know it well, because for years I’ve run after women, nothing attracts me more, yet I’m always given the cold shoulder. Argilla - (Ah, rascal! Wait a minute and I’ll warm you up). (Coming forth) My charming dumpling! Show me your hand, let me look into your mischievous eyes, I wish to predict your future. Papaccione - (Ah, what a succulent piece of meat! A morsel fit for the great Jove! She may indeed tell me something about my past and future). Argilla - So, don’t you want to know the horoscope of your planet? Papaccione - This comet I’m looking at has revived me. Argilla - When you were a lad you hanged around with low-class people; a jester and a madcap, you never studied, always loafed around: and a certain Tommasina once made you sigh. 31 Papaccione - (Chesta affé ca nce annevina! Col tentillo stà a parlà). Argilla - Quella tua cambiamonete ti fe’ un giorno un brutto trucco, e tu gonzo, e mammalucco ti facesti corbellar. Papaccione - Lassa stà le cose antiche, si se Zingara addavero, quel ch’io tengo nel penziero, tu m’aje indovinà. Argilla - Io l’ho bello e indovinato: sei di me già innamorato, e vorresti sul momento la mia mano palpizzar. Papaccione - Figlia mia, sì no portento! Viene a tata, fatte ccà. Argilla - (Nella rete è già il merlotto, tutto arride al mio disegno, superar saprò l’impegno son gran donna in verità!) Papaccione - (No sta Zingara, pé bacco, non bà appriesso alle galline, ma dell’uomene a dozzine esterminio sape fa). 9 Argilla - Dico, hai finito o no di stringermi la mano? Papaccione - E che pressa che tiene? Nuje stammo ancora a l’introduzione, e tu già vuò arrivà a lo finale? Argilla - Vogliamo fare all’amore? Papaccione - Volimmo fa l’ammore? Io già sto penzanno a la notriccia del primo, seconno, terzo, quarto, e quinto rapollo! Argilla - Piano, le zingare sono difficili ad innamorarsi, siamo esseri erranti: eppure io sento per te una vera inclinazione amorosa. Splende un astro sulla tua fronte, che fa impazzire tutte le donne! Papaccione - (Has she ever hit the nail on the head! She must be in contact with the devil). Argilla - That lady swindler of yours once set up a nasty trap for you, and you, simpleton, fell right into it. Papaccione - Leave the past alone, if you’re really a gypsy you must tell me what’s in my mind right now. Argilla - That’s easily said: you’ve fallen in love with me and would like here and now to hold my hand. Papaccione - My girl, you’re a wonder! Come to your daddy, come close. Argilla - (This fool is already in the net, everything is going in the right direction, I’ll be up to my task, I’m such a great woman!) Papaccione - (This gypsy, by Jove, doesn’t play around with jackasses but knows how to play havoc with men’s hearts). 9 Argilla - Say, haven’t you held my hand long enough? Papaccione - What’s your hurry? We are just at the introduction and you already want to get to the finale! Argilla - Shall we flirt? Papaccione - Flirt? I’m already thinking of the wet nurse for our first, second, third, fourth and fifth baby! Argilla - Easy! Gypsies rarely fall in love, we are wandering beings: yet I feel for you a real attraction. A star shines on your brow, which makes women go head over heels in love with you! 32 Papaccione - Ma quale astro e astro! L’ast’astro mio, sta ecclissato. Quanno correvano chelle cose rosse, e tonne, che se chiammano doppie, l’astro mio veramente luceva, comm’a no sole, e sa comme correvano le femmene a ricerverne i benigni influssi? E a forza d’influssi, e di continui flussi, e riflussi, so restato senza lustro, e senza felusse. Argilla - Ma qui sei ora bene impiegato? Papaccione - Vuò pazzià! Poco ce vò, e metto carrozza: io ccà aggio fatto ascenzi rapidissimi. Da mercante dè baccalà, ch’era a Napole, per non dare molestia ai miei puntualissimi debitori, penzaje de mutà aria. E così m’arremediaje scorte de sto don Ciuccio. Argilla - Don Rannuccio. Papaccione - No, no: Don Ciuccio, anzi ciuccissimo: ca mmece de farme suo maggiordomo, me tene ccà alla custodia de ste fraveche vecchie, addò sta stipato no povero viecchio, e consegnato a me vita pè bita. Argilla - E chi è costui? Papaccione - E chi lo po appurà? Nce sarria pena de lo cuorio, si ce l’addimmanasse: lo poverommo me fa tanta compassione, quanno se magna chillo piezzo de pane niro, e pesante quanto a na savorra, e se veve chell’acqua, addò li vierme se spassano a ballà no valzon. Argilla - (Ne devo conoscere l’intrigo) Quando è così, ascoltami attento, io vengo a renderti doppiamente felice; sappi che le stelle mi hanno svelato che in questo castello si nasconde un immenso tesoro, del quale è a te destinato l’acquisto. Papaccione - No tesoro! O grande eroina di tutto il ceto zingaresco! No tesoro! Tu dice addavero? E addò stà? Argilla - Questo mi resta ancora a scovrire. Lascia che consulti nuovamente le stelle. Papaccione - Oh mmalora! Me faje venì a mente no suonno, che aggio fatto stanotte! Papaccione - What star! My star is eclipsed. When those shiny and round things that go by the name of doubloons filled my pockets, my star shone like a sun and plenty of women ran to get its benign influence! But by dispensing influence left and right my sun was left without its shine, and I without my money. Argilla - And now, have you got a good job here? Papaccione - You bet! I am nearly a big shot: I’ve gone ahead by leaps and bounds. In Naples I used to sell dried cod, but then, not wanting to bother my very punctual debtors, I decided to clear out. And so I landed a job in the guard of this Master Jackass. Argilla - Don Ranuccio. Papaccione - I mean Jackass, that dimwit: instead of making me his valet, he’s posted me to this decrepit clink in which he keeps an old wretch, and I am to be his warder for life. Argilla - And who is he? Papaccione - Who knows? I’d be skinned alive if I tried to find out: the poor fellow arouses my pity when he bites into his piece of black bread, as stale and hard as a piece of wood, and drinks his water, in which worms are having a great time dancing a waltz. Argilla - (I must find out about this mystery) Now listen to me carefully, I will make you doubly happy; I must tell you that the stars have revealed to me that a huge treasure is hidden in this castle, to which you alone are entitled. Papaccione - A treasure! O greatest heroine of all the gypsy ranks! A treasure! Are you sure? And where is it? Argilla - This is something I must still find out. Let me consult the stars once more. Papaccione - Goodness gracious! You have reminded me of a dream I had last night! 33 Argilla - Raccontalo pure: gli alti destini si palesano talvolta ne’ sogni. Papaccione - Siente, m’aggio sonnato, ca io teneva n’appuntamento, pè ghì a parlà a lo patre de na certa commara mia, che a Napole me stira la biancaria. So ghiuto, e aggio trovata la porta de lo vascio spaparanzata. Argilla - Di un basso? Papaccione - Sì… pecchè io so curto de gamme, e me pesa de saglì gradiate. Ma comme io aveva da farle no discurzo a luongo, me so nfeccato… e che metamorforsion! Che aggio visto! Lo vascio se n’era fojuto, e mmece c’era no cammarone, che non feneva maje; e llà dinto chello, che non bolive non ce trovave… frutte de dispenza, bottigliaria, robbe de zuccaro jettate pe terra… nzomma pareva la casa de la grassa, e de l’abbonnanza. Argilla - Vedi? E’ il deposito del tesoro! Papaccione - Me so botato attuorno, e n’aggio visto nisciuno, eh! La vista de tanta belle cose cellecava il mio desiderio… aggio pensato de farme na provistella pè na quarantina d’anne. Ah! no l’avesse maje fatto! Da do mmalora so asciute tanta voce annascoste!… lassa! mariuolo! ferma! assassino! non te movere! Mazzate, chianette, cauce, schiaffone… Pim! Pum! Pam! E m’hanno fatto comme Santo Lazzaro primma e San Sebastiano co’ frecce dopo. Argilla - Lo sapevo: gli invisibili custodi! Papaccione - Tutto nziemo è comparsa na bella Foretana tutta chiena d’oro, e lazzette, e m’ha ditto “Papaccione prendi tutto chello che vuoi”. E così io aggio fatto na provvistella de cose belle, e me na so tornato a la casa carreco, e co na sporta chiena de robba la chiù squisita. Argilla - Quella donna... sono io! Papaccione - Sei tu la bella Foretana! Viene ‘cca allora! Argilla - Tell me about it: dreams sometimes reveal a person’s destiny. Papaccione - Listen, I dreamed that I had an appointment, I was to go and speak to the father of a certain lady who pressed my laundry in Naples. I went then, and found the door to the basement wide open. Argilla - A basement? Papaccione - Yes… my legs are short and I have a hard time with stairs. But since I had to give him a long speech, I went down and … what a metamorphosis! Oh wonder! The basement was no longer a basement, it was a huge room of which I couldn’t see the end; and inside it was all that one could dream of… piles of pantry goods, bottles, sugar candies covering the whole floor… in short, it looked like the land of plenty. Argilla - You see? That’s the treasure’s chamber. Papaccione - I turned around and saw nobody. Well! The sight of so many good things made my mouth water… I thought I’d put together a nice little supply for some forty years. Ah! Would that I had never done that! From heaven-knows-where came mysterious voices! … let go! rascal! stop! murderer! Smack! All of a sudden came blows, clouts, kicks, slaps… and then I was like Saint Lazarus and Saint Sebastian with all the arrows. Argilla - Of course: the invisible guardians! Papaccione - Suddenly a beautiful girl appeared, all covered in gold and lace, and she told me “Papaccione, help yourself to all that you wish”. And so so I made myself a nice supply and went back home loaded up like a pack-horse, with a bag full of the most delicious things. Argilla - That woman... is me! Papaccione - So you are the beautiful girl! Come here, come close! 34 Scena IV Antonio, e detti. Scene IV Antonio, and the above. Antonio - Papaccione, chiede di te Don Rannuccio. Papaccione - (Fuss’acciso tu, e isso!) Antonio - Ti vuole all’istante, presto! Papaccione - Mo bengo. Argilla - (Ti attenderò, va pure). (Papaccione parte con Antonio) Saprò col pretesto di rintracciare il tesoro, discendere con Papaccione in quel sotterraneo, e scovrire chi sia quell’infelice, ch’è là sepolto… Antonio - Papaccione, Don Ranuccio is asking of you. Papaccione - (Curse you and him!) Antonio - He wants you immediately, come now! Papaccione - I’m coming. Argilla - (I’ll wait for you, go). (Papaccione leaves with Antonio) With the excuse of looking for the treasure I will introduce myself in that dungeon with Papaccione and find out who is the wretch that is buried there... Scena V Luogo sotterraneo, ove è in prigione Sebastiano Alvarez. Sebastiano, animato dalle parole di Argilla, che poc’anzi ha sentito, vien fuori piuttosto lieto e dice Scene V Underground dungeon, where Sebastiano Alvarez is kept prisoner. Sebastiano, revived by the words that Argilla has just spoken, appears and says 10 Sebastiano - Se il Cielo permetterà che questa supplica sia raccolta da un amico della giustizia, imploro costui a muoversi a compassione di un vecchio afflitto e senza speranza! Breve istante di pace! A che lusinghi lo straziato mio cor? V’ha sulla terra chi geme ancora al pianto mio? Chi sente ancora di me pietà? Donna celeste! Sei tu che favellasti? Ah sì… prosiegui, se già la pena mia rendi men grave, a scendermi nel cor voce soave! 11 Se un lampo passegger diè calma al mio martir, da me più non fuggir dolce speranza! Ma che spero! Qual vana 10 Sebastiano - If Heaven will grant that my plea is heard by a law-abiding person, I beseech him to be moved to pity of this afflicted and unhappy old wretch! Brief moment of peace! Why do you beguile my tortured heart? Is there still on earth someone who feels sorrow for my tears? Who takes pity on me? Celestial woman! Was it you who just spoke? Ah, yes… gentle voice, if you can make my suffering less painful, keep sinking into my heart! 11 Sweet hope, which, for a fleeting moment assuage my suffering, leave me no more! Alas, I hope in vain! What vain illusion 35 illusion mi alletta i sensi? È morte, che sol mi attende… è morte, che squallida e feroce minaccia i giorni miei. Figlia… nipote… agi… grandezze… ah tutto il destin mi rapì! Solo mi resta di un crudele avvenir l’idea funesta! 12 Perché non basto a frangervi o barbare catene? Perché la mia canizie, sa tollerarvi ancor? Tiranno inesorabile! Tu godi alle mie pene? Ma trema! A prò de’ miseri v’è un Dio vendicator. Oimè! Già oppressa è l’anima, già langue il mio vigor!… Tu Cielo a queste lagrime, figlie del mio dolore, disarma il tuo rigore, abbi pietà di me! Ottenga il tuo favore chi sol confida in te! flatters my senses? Only death awaits me… dreary, merciless death, which threatens my days. Daughter… nephew… comforts… rank… alas, fate robbed me of them all! All that is left to me is the bleak prospect of a fatal destiny! 12 Why can’t I break you, cruel fetters? Why, old as I am, I still endure you? Relentless tyrant! You, who take pleasure in my pain, must tremble! The wrath of God avenges those who suffer. Alas! My soul grows heavy, my strength is failing!… Heaven, before these tears, the daughters of my sorrow, moderate your rigour, have mercy on me! May he that trusts in you alone be granted your favour! Scena VI Papaccione, Argilla, e detto. Scene VI Papaccione, Argilla, and the above. 13 Argilla - Gli astri di Venere e Mercurio mi dicono che sotto queste volte sotterranee siano celate le ricchezze a te destinate, ed io, premurosa della tua sorte, ho voluto seguirti, per assicurarmene da me stessa. Papaccione - Tu addò te mpizze? Dì la verità, mmece de lo tesoro, avisse golio de farme passà no guajo? Si Don Zappatore appura, ca ccà bascio 13 Argilla - The stars of Venus and Mercury have given me certain hints pointing to the fact that the riches destined to you are hidden in one of these underground rooms and, having your fate at heart, I have decided to go with you to make sure. Papaccione - What are you up to? Tell me the truth, could it be that there’s no treasure and you want to get me into trouble? If Don Zappatore finds 36 out that a gypsy’s been down here, tomorrow he’ll make mince meat of me. Argilla - Nitwit! You have Argilla at your side! Don’t you know that Fortune favours the brave? Who’s that? Papaccione - The prisoner! I told you! Argilla - Is he asleep? Papaccione - Either he is asleep or the poor thing is absorbed in his troubles. Argilla - Do you see that beam of light flashing across his brow? Papaccione - What beam? Those are spider’s webs hanging from the ceiling. Argilla, for you anything is something! Be careful, for he hasn’t had a morsel of meat in a long time... Argilla - (She approaches Sebastiano). (Don Sebastiano...) Sebastiano - (Ah! Who is calling me? How do you know my name?) Papaccione - Damn gypsy! Argilla - (I am the one who heard your plea … I will free you from your prison...) Sebastiano - (Oh unique woman! Ah! Thanks be to God, who has sent you!) Papaccione - Hey there! Hurry up... I’m hungry! Argilla - (Cheer up, Don Sebastiano! Tonight I will come down and break your fetters, trust me). Papaccione - The gypsy must’ve come to terms with Mercury. Argilla - Let’s go, Papaccione. Papaccione - Let’s go! Have you found anything out? Argilla - Everything… let’s go, I tell you. Papaccione - And my treasure... where is it? Argilla - Come with me and you’ll know everything. Get a move on! Papaccione - Let’s go then, my beauty, I’m sure you can wriggle out of this muddy situation like an eel. è trasuta na zingara, dimano sta capo mia porposa se la cucina ammollicata a lo furno. Argilla - Imbecille! Sei al fianco di Argilla! Non sai, che la fortuna è amica degli audaci? Chi è costui? Papaccione - Lo prigioniero! Che t’aggio ditto! Argilla - Dorme? Papaccione - O dorme, o lo poverommo starà penzanno a li guaje suoje. Argilla - Vedi quella striscia di luce, che gli brilla sulla fronte? Papaccione - Qua striscia? Chelle so felinie, che scenneno dalla soffitta. Argì, tu piglie ogni zaro de no cantaro l’uno! Vi ca chillo non magna carne da no secolo... Argilla - (Si avvicina a Sebastiano). (Don Sebastiano...) Sebastiano - (Ah! Chi mi chiama? Come sapete il mio nome?) Papaccione - Oh! Mmalora nzordiscela! Argilla - (Sono colei che ha raccolto la vostra supplica… basterò a trarvi da questa prigione…) Sebastiano - (Oh donna incomparabile! Sono grato al Cielo che vi ha mandata!) Papaccione - E bide de te spiccià... ho fame! Argilla - (Coraggio, Don Sebastiano! Questa notte verrò a sciogliere le vostre catene, fidate in me). Papaccione - La zingara s’è posta d’accordo cò Mercurio. Argilla - Andiamo Papaccione. Papaccione - Andiamo! Aje appurato niente? Argilla - Tutto… andiamo ti dico. Papaccione - E lo tesoro mio... addo stà? Argilla - Vieni con me, e saprai tutto. Muoviti! Papaccione - E ghiammo bella mia, tu aje da essere l’anguilla de sto pantano. 37 Scena VII Amena campagna; veduta dell’esterno del castello di Zappador. Dalla campagna Fernando e Sguiglio in abiti succinti, poi Argilla. Scene VII Pleasant countryside; view of the outside of Zappador’s castle. Fernando and Sguiglio, dressed in simple clothes, from the country; then Argilla. 14 Argilla - (Presentandosi) Coraggio Don Fernando! Amor vi guida in porto… vada la tema in bando, è il Ciel per voi seren. Fernando - Che ascolto! E voi chi siete? Sguiglio - (Simmo scopierte a ramma!) Fernando - Il nome mio sapete? Sguiglio - (Auzammo mo la gamma, si no so guai, messè!) Argilla - Son la consolatrice de’ cori innamorati: son l’araba fenice né casi disperati: risorge a nuova vita ogni amator per me. Sguiglio - ‘Npara quanno è chesso pe mme no caso brutto; nel mio vorzillo asciutto la mbrumma fa cadè. Fernando - Deh taci! Argilla - E’ un vile Sguiglio tempo a pensar non è. Sguiglio - Porzì sa il nome mio? Fernando - Oh Ciel! Che mai degg’io, donna, pensar di te? Argilla - Un essere pietoso, un genio in me tu miri, che a crudi tuoi martiri qui venne a dar mercé. Coraggio! 15 Fernando - (Costei mi sorprende! 14 Argilla - (Coming forward) Take heart, Don Fernando! Love will carry you through… do not worry, the heavens are in your favour. Fernando - What do I hear! Who are you? Sguiglio - (We have already been discovered!) Fernando - How do you know my name? Sguiglio - (Let’s take to our heels, or we’ll be in trouble, master!) Argilla - I am the comforter of hearts in love: I am the Arabian bird of desperate situations: every lover through me resurrects to new life. Sguiglio - I tell you, this is a nasty situation: let a coin drop in my empty purse. Fernando - Be quiet! Argilla - Sguiglio is a coward, there is no time to waste. Sguiglio - Does she know also my name? Fernando - Heavens! What shall I make of you, woman? Argilla - You have in front of you a merciful being, a fairy who has come to rescue you from your cruel suffering. Cheer up! 15 Fernando - (She startles me! 38 Confuso mi rende!… Fidarmi non deggio, se dubito è peggio… Nel fiero conflitto di speme e timore Il povero core la calma perdè!) Sguiglio - (Ca chesta è ghianara la cosa è già chiara… Ma tene na vocca che l’arma te ncrocca… Chill’uocchio mmalora! Il core affattora… Ca Sguiglio è sguigliato, cchiù dubbio non nc’è!) Argilla - (L’amico è smarrito, Il servo è stordito. Sta l’un sospettoso, è l’altro dubbioso. Grazioso è l’istante - mi alletta mi piace, il povero amante è fuori di sé!) (Essi non sanno che ho sentito il loro discorso, che all’alba facevano seduti nel vicin prato). 16 Fernando - Donna, dilegua i miei dubbi, e dimmi chi sei… Argilla - Argilla, la celebre zingara. Sguiglio - Ah! Vuje site la siè Petronilla? Fernando - Ed il vostro sapere è tale… Argilla - Che niente a me resta celato. E... Voi siete un giovane innamorato, che qui venite sotto mentite spoglie ad avere notizie della bella Ines. Sguiglio - Statte zitto! Non saje ca cierte berità non sempe se ponno dicere? Fernando - Bene, se tutto ti è noto, dimmi un po’, cosa sta facendo la mia cara Ines? Argilla - Non pensa che a voi; Fernando - Oh me felice! Sguiglio - E... chella cammarera arraggiosa sta ancora co essa? Fernando - Potrò dunque rivederla? Argilla - Certo, anzi questo potrebbe essere il momento opportuno: son tutti fuori ad accogliere il Duca di Alziras. Fernando - (Mio fratello in questo palazzo!) Argilla - Entrate: vado a chiamare la vostra Ines, così potrete parlare con lei a vostro piacere. She muddles me!… I should not trust her, but to doubt her is even worse… in this fierce conflict between hope and fear my poor heart has lost its peace!) Sguiglio - (That she is a trickster is a sure thing… But with her words she clutches your soul… Her eyes, my goodness! Bewitch your heart… Sguiglio you’ve been grazed, that’s for sure!) Argilla - (The master is confused, the servant befuddled. The one is suspicious, the other in doubt. It’s such a good moment - it’s tempting, I like it, the poor man in love is beside himself!) (They ignore that I overheard their conversation, at dawn in the nearby meadow). 16 Fernando - Dispel my doubts, woman, and tell me who you are... Argilla - I am Argilla, the famous gypsy. Sguiglio - Ah! It is you the lady Intrigante! Fernando - And your knowledge is such that… Argilla - That nothing can be kept from me. And... you are a young man in love, who has come here in disguise to have news of the fair Ines. Sguiglio - Hush! Don’t you know that some truths cannot be told? Fernando - Well, if you know everything, tell me: what is my beloved Ines doing? Argilla - She thinks only of you; Fernando - Oh, happy is me! Sguiglio - Tell me one thing… is her rabid maidservant still with her? Fernando - Will I then be able to see her? Argilla - Of course; and this might actually be the best moment: everyone is out, busy welcoming the Duke of Alziras. Fernando - (My brother in this place!) Argilla - Go inside: I will fetch your Ines so you can speak to her. 39 Sguiglio - Ebbiva la gallotta mpastata! Fernando - Shhhh! Argilla - Attenti: ci sono Antonio e Ranuccio! Nascondetevi da quella parte, presto! (Si nascondono dietro a dei cespugli e non appena Don Ranuccio e Antonio sono usciti si introducono nel castello). Sguiglio - Hurrah for our sly fox! Fernando - Hush! Argilla - Watch out! Here come Antonio and Don Ranuccio! Hide over there, quick! (They hide behind a bush and, as soon as Don Ranuccio and Antonio come out, quickly slip inside the castle). Scena VIII Don Ranucccio, ed Antonio dal castello, Argilla in ascolto. Scene VII Don Ranuccio and Antonio, coming from the castle, and Argilla eavesdropping. Ranuccio - Sai benissimo, che per farti possessore dell’immensa fortuna di Don Sebastiano, tuo zio, io lo feci dai miei fidi sorprendere di notte e trasportare in questo palazzo, dov’è sepolto da anni. E... dimmi ora: cosa chiesi in cambio della mano di mia figlia? Antonio - La mia cieca obbedienza. Ranuccio - Bravo Antonio! Ascolta dunque. Doveva il Re scegliere fra suoi distinti sudditi il più meritevole per innalzarlo alla luminosa carica di Ministro. Ma l’invidia e le trame dei miei nemici furono tali che la scelta cadde sul Duca di Alziras. Giurai però a miglior tempo vendetta, ed eccone finalmente giunto il momento. Antonio - Come? Ranuccio - Avvicinandosi a queste contrade, egli ha deciso di trattenersi per qualche giorno nel mio palazzo. Alla tua mano è riserbato di compiere la mia vendetta. (Ranuccio guarda intorno, brandisce cauto un pugnale, indi con espressione marcata dice ad Antonio) 17 Ecco un pugnal… su… celalo… giunge l’amico istante, vicina è già la vittima Ranuccio - You know that to make you come into possession of the immense fortune of Don Sebastiano, your uncle, I had my followers lay an ambush for him and had him moved at night to this castle, where he has remained imprisoned in the dungeon. Tell me now: what have I asked in return for my daughter’s hand? Antonio - My blind obedience. Ranuccio - Good, Antonio! Listen, then. The king was to chose the most deserving of his eminent subjects and raise him to the shining rank of Minister. But the envy and the plots of my enemies resulted in having him prefer the Duke of Alziras. I swore, however, that when the right time came I would take my revenge, and luckily that moment has arrived. Antonio - How? Ranuccio - The Duke is coming to this part of the county and has decided to stay a few days in my castle. Your hand will be entrusted with the task of carrying out my revenge. (Ranuccio looks around himself, stealthily seizes a dagger, and then tells Antonio gravely:) 17 Ranuccio - Here is a dagger… hide it… the favourable moment is coming, the victim is already near, 40 serbata al mio furor. Allor che del silenzio spande la notte il velo, scagliati a lui, sorprendilo nel primo suo sopor. Aprigli il petto, ed avido cerca quell’empio cor… a brano a bran poi strappalo, o mio vendicator! Ad animarti il braccio avrai l’averno istesso, che alimentò represso l’antico mio livor. (Antonio resta dubbioso) Ma tu vacilli! Ah debole! Palpiti dubbio ancor? E ben quel ferro rendimi… rinunzia alla tua sorte… d’Ines mai più consorte… di me… va! non sei degno… Non manca al mio disegno più ardito esecutor. (Si sentono voci di pastori da lontano). Voci - Il Duca! Evviva! Evviva! Ranuccio - Quai voci? Voci - Oh qual favore! Di così grande onore esulti ogni pastor. 18 Ranuccio - Ah vile! Ah iniquo Antonio! Antonio – (risoluto) Vile non son… mi avrai Fido a’ tuoi cenni. Ranuccio – (con tutta l’espressione del piacere) Abbracciami! Sarai felice appieno: tutte le sue delizie già ti prepara amor. Piacer della vendetta! ready for my wrath. When night will veil everything with silence, you must pounce upon him, surprise him in his sleep. Rip his breast open, look for that wicked heart… and tear it out, my avenger! Hell itself will spur you on, the same hell that has kept my repressed hatred alive. (Antonio looks uncertain) You are wavering! Ah, weak man! Are you still torn by doubt? Well then, return that dagger… give up your fortune… you will never marry Ines… go! You are not worthy of me… I’ll find a bolder executor for my plan. (Shepherds’ voices echo from far) Voices - The Duke! Hurrah! Hurrah! Ranuccio - What are these voices? Voices - What a privilege! Every shepherd must rejoice in such a great honour. 18 Ranuccio - Ah coward Antonio! Wicked man! Antonio – (With determination) I am no coward… I’ll do what you want. Ranuccio – (With delight) Embrace me! Your happiness will be complete: love is already preparing for you all of its delights. Pleasure of revenge! 41 Tu scendi già in quest’alma! Raggio d’amica calma Spero del tuo favor. (abbraccia Antonio e parte con lui verso il villaggio) 19 Argilla – Ah, mostro! Ma il destino mi ha qui mandato a render vani i tuoi infami disegni. (Entra nel castello). I can already taste you! Ray of friendly peace, I trust in your help. (He embraces Antonio and leaves with him towards the village). 19 Argilla – Ah, monster! But fate has lead me to this place so that I can thwart your wicked plot. (She goes inside the castle). Scena IX Interno del castello come prima. Ines ed Amelia: poi Fernando e Sguiglio in osservazione; indi Argilla, infine Papaccione. Scene IX Interior of the castle as before. Ines and Amelia: then Fernando and Sguiglio on the lookout; then Argilla, finally Papaccione. Argilla - (Presentandosi a Ines ed Amelia). Salute e prosperità a questa coppia gentile! Sono Argilla, il più grande oracolo del secolo! Amelia – Che pazzie, indovinare l’avvenire! Sguiglio – (Ah, cano! Non te movere: aspettammo la zingara, si nò facimmo asso e asso). Argilla - (Ad Amelia) Venite, venite qua... ho necessità di osservare la vostra fisionomia, non già la mano. Quell’occhio mi dice... che avete un core sensibilissimo, ma che siete stata mal corrisposta dai vostri amanti. Attendetemi un momento. (Nel punto che Argilla lascia Amelia, si presenta a costei Sguiglio, e procura trattenerla colle spalle ai due amanti. Argilla attraversa sollecitamente la scena, e trattiene Papaccione nascondendo colla sua persona i due amanti, che sono in fondo). Sguiglio - Scusasse, siete voi a donna Ammennelia? Amelia - Amelia, vorrai dire. Sguiglio - Gnorzì, chesta è essa. Amelia - E tu chi sei? Argilla – (Introducing herself to Ines and Amelia) Health and prosperity to this gentle pair! I am Argilla, the greatest fortune teller of the century! Amelia – What stupidity, to foretell the future! Sguiglio – (Ah, don’t budge! Let’s wait for the gypsy lady, or we’ll get into scrapes). Argilla - (To Amelia) Come, sit here... I need to look at your face, not your hand. Your eyes tell me that you possess a very sensitive heart, but that your suitors have not returned your love. Wait for me, I’ll be back shortly. (As soon as Argilla leaves, Sguiglio appears before Amelia and makes sure that she keeps her back to the two lovers. Argilla rushes across the stage and withholds Papaccione, hiding with her body the two lovers, who are in the back). Sguiglio - I beg your pardon, are you the lady Ammennelia? Amelia - You mean to say Amelia. Sguiglio - Yes, her. Amelia - Who are you? 42 Sguiglio - Il primo paggio de lo Duca Zisso… Amelia - Zisso! Sguiglio - Sì, del Duca d’Alziras. M’hanno ditto ca vuje site la factota de casa. Amelia - Ebbene? Sguiglio - Tenisse vo pe’ caso... na cammeretta,no lettino, na stanzuella... no buco? Amelia - Che so io di alloggi? Sguiglio - Mo! E sta mala grazia comme c’entra? Me parite na Luna nquintadecima, e non bolite fa no poco de luce a no poverommo che bedenno i vostri arraggiati riflessi s’ha ntiso tutte nzieme pè buje ah! Amelia - Mancava quest’altro matto a darmi molestia! 20 Ines - (Ah! Come sul mattin a primi rai del Sol spiegando l’usignol con flebili concenti va l’innocente ardor, ora che a te vicin mi veggo, o caro ben, tutte narrarti appien vorrei con brevi accenti le pene del mio cor. Ma così bei contenti non mi concede Amor). Fernando - (Pace non so trovar, cara, lontan da te. Tutto è languore in me, splendor non han le stelle, natura è a me d’orror. Ma il crudo mio penar già cangiasti in piacer, ora che il nume arcier dalle tue luci belle nuovo mi dà vigor. Ahi! In quelle tue fiammelle Sguiglio - The valet of Duke Zisso… Amelia - Zisso! Sguiglio - Yes, of the Duke of Alziras. I have been told that you are the factotum of the house. Amelia - And so? Sguiglio - Would you, by any chance, have accomodation... a room, a bed... a hole? Amelia - What do I know about accomodation? Sguiglio - Goodness! Why all this rudeness? A full moon like you who doesn’t want to shed a little light for this poor man who, seeing your reflections, has become enraptured only to get ah! his heart scratched! Amelia - Another bothersome fool is all I need! 20 Ines - (Ah! Just like in the morning, at the first rays of dawn, the nightingale with soft chirps displays its innocent happiness, now that I am near you, my beloved, I wish I could explain to you, with simple words, all the sufferings of my heart. But Love does not grant me such happiness). Fernando - (My dear one, far from you I have no peace. Everything seems dreary, stars do not shine, nature looks grim. But my cruel suffering has turned into pleasure, now that Love gives me new vigour through your fair eyes. Ah! I long to lose myself forever 43 struggermi io bramo ognor!) Argilla - Quando il gufo a mezza notte canterà colla civetta, io sollecita, e soletta la tua porta busserò. Ticche, tocche, ticche, to… Zitto, e pian mi seguirai, e in quel pozzo scenderai, che indicarti io ben saprò. I custodi del tesoro, Belzebucco, ed Astarotte, pria di venderti quell’oro, ti daran delle gran botte, Papaccion, niente paura! Brutti mostri appariranno, Sfingi, scimie, ombre, giganti, De’ gran turchi con turbanti… Papaccion, niente paura! Col coraggio e la bravura sol puoi ricco diventar. Papaccione - Quanno sento il gran duetto tra lo gufo, e la cevetta, il me metto a la veletta e il rilorgio sentarò… Nti, nti, nti, nti, nti, nti, nto. Comm’a ladro de campagna, che dà ncuollo a li viannante, assacheo chella coccagna, piglio argiento, oro, e brillante, zingaré, n’aggio paura: pe Astarotte, e Barnabucco stanno ccà le spalle meje. Non so tanto mammalucco, signornò, n’aggio paura, lo coraggio, e la bravura schitto ricco m’ha da fa. Sguiglio - E botame nfaccia in those tongues of flame!) Argilla - At midnight, when the owl and little owl sing, I will come all alone to knock on your door. Knock, knock… Quiet, softly, you must follow me, and lower yourself into the cistern that I will show you. The treasure’s guardians, Beelzebub and Astarotte, before letting you take the gold away, will give you a good thrashing; but have no fear, Papaccione! Horrible monsters will appear, sphinxes, monkeys, ghosts and giants, huge Turks wearing turbans… but have no fear, Papaccione! Only by showing courage and cleverness will you become rich. Papaccione - When I hear the nice duet of the owl and little owl, I must stand ready and listen for the clock… Tick-tock, tick-tock, tick-tock. Like a country thief who pounces on people, I will fall upon that treat and grab the silver, gold and jewels, gypsy mine, have no fear: for Astarotte and Beelzebub I have shoulders that are wide enough. I am no nitwit, no sir, I have no fear, only courage and cleverness can make me rich. Sguiglio - And turn those eyes 44 chill’uocchie siè Amè! Ca voglio sta caccia stirpamme pe me. Amelia - Più smorfie non farmi, Sei matto? Va là! Un nano di amarmi ardir non avrà. Sguiglio - Diceva zi Ciommo, lo dotto, e saputo, a parme dell’ommo mesura maje fu. Si provi non poco chi è sto nennillo, ca so peccerillo te faccio scordà. Amelia - Io mai con ragazzi il tempo ho perduto; mi è sempre piaciuto più l’uomo di età. Te’l dissi, e ridico, per me tu non fai, va trovati amica qualche altra beltà. 21 Ma zitto! (Il vicino suono di pastorali istrumenti che annunzia l’arrivo del Duca, frastorna gli amanti). Argilla - (Il Duca arriva!) Fernando - (Oimè! Giunge il germano!) Sguiglio - Ma sienteme… va chiano… (Trattenendo sempre Amelia). Papaccione - Restato s’è accrossi. (Esce per dove è entrato). Amelia - Andiamo, signorina… (Si sviluppa da Sguiglio, e sorprende i due amanti). Che vedo! Ah! Malandrina! Ah zingara briccona! to me, lady Amelia! I want this hunt to be only mine. Amelia - Stop pulling faces at me, are you crazy? Go away! A midget cannot aspire to my love. Sguiglio - My uncle Ciommo, a wise and knowledgeable man, used to say that one does not measure manhood by inches. If you spend some time with this little boy, I’ll make you forget about my size. Amelia - I have never wasted my time with boys; I’ve always been attracted by men of a certain age. I’ve told you once and tell you again, you are not for me, go find yourself some other beauty. 21 But hush! (The sound of shepherds’ instruments, announcing the arrival of the Duke, distracts the two lovers). Argilla - (The Duke is arriving!) Fernando - (Alas! My brother is here!) Sguiglio - Listen to me… wait… (Still withholding Amelia). Papaccione - We’re understood. (He leaves by the same way he entered). Amelia - Let us go, mistress… (She frees herself from Sguiglio and catches the two lovers). What is this! Ah! Rascal! Ah, wicked gypsy! 45 Così mi si canzona? E tu giovane ardito se qui più inoltri il piede, vedrai cosa succede, qual danno ti avverrà. Ines/ Fernando - D’un core innamorato, Amelia mia pietà! Sguiglio - Finiscela sta joja, non bì ca so picciune? Me pare affè na groja, n’arma de baccalà! Amelia - Mi soffoga la rabbia, mi salta il malo umore, partite, allontanatevi, o adesso io do in furore, e invero la commedia tragica finirà. Ines/ Fernando - Se il fato inesorabile si oppone al nostro amore, mia bella fiamma, ah! serbami il tuo costante ardore, la morte sol dividere il nostro cor potrà. Argilla - (Fidate nella zingara, fidate nel mio core, non mancheranno astuzie all’alto mio valore, sì, questo ingegno fervido vittoria canterà). Sguiglio - (A Fernando) (E priesto mo finiscela! E scumpela, signore! Vi ca si vene frateto, ccà nasce lo rommore, na chioppeta de scoppole la sento mo assommà!) (Amelia prende per mano Ines, e la conduce seco; Is this the way you trick me? And you, bold young man, don’t you dare set foot in here again, or you’ll be in trouble, and you’ll pay the consequences. Ines/ Fernando - Amelia, have mercy on this heart in love! Sguiglio - Give them a break, don’t you see that they are turtledoves? You ugly face, cold-blooded soul! Amelia - I’m choking with anger I’m getting into a bad mood, leave, go away, or I shall lose my temper, and then this comedy will have a tragic finale. Ines/ Fernando - If a cruel fate opposes our love, my fair idol, ah! bear me your unflinching passion; death alone shall divide us. Argilla - (Trust this gypsy, trust my heart, I have great talent, I know plenty of tricks, yes, my fervid imagination will make us victorious). Sguiglio - (To Fernando) (Enough now! Bring it to an end, master! If your brother comes he’ll kick up a row, he’ll give us a hail of blows, I can feel it coming!) (Amelia takes Ines by the hand and leads her away; 46 Fernando e Sguiglio si allontanano, ed Argilla va a raccogliere i suoi seguaci). Fernando and Sguiglio leave, and Argilla goes to gather her followers). Scena Ultima I domestici di Don Ranuccio precedono festivi il Duca di Alziras, al di cui fianco è Don Ranuccio, e Don Antonio. Segue il corteggio del duca. Poi Papaccione alla testa di altri Domestici, infine Argilla con Ghita, Manuelitta ed altri zingari. Final Scene The servants of Don Ranuccio precede in festive mood the Duke of Alziras, at whose side are Don Ranuccio and Don Antonio. The duke’s retinue follows. Then Papaccione at the head of other servants, finally Argilla with Ghita, Manuelitta and other gypsies. 22 Coro - Feste, gioje, delizie, piaceri, cacce, pranzi, spumante, bicchieri… Serva tutto a mostrar qual contento in noi desti sì lieto momento, come ogni alma festiva, baccante sia superba di tanto favor! 23 Duca - Basta, o amici; ah troppo cari sono a me quei dolci accenti! Quai soavi, e bei momenti fa gustarmi il vostro amor! Se mi accoglie in queste mura amistà leale, e pura, sarò lieto in fra i piaceri che mi appresta il suo candor. Ranuccio - Sì, ti accoglie in queste mura di amistade il bel candor. Coro - Amistà leale, e pura! Sei la gioja di ogni cor. 24 Papaccione - (Con caricatura) Papaccione Cincorenza, che i doveri non attrassa, al magnifico Eccellenza or s’inchina, e ’l capo abbassa, e ad un uom si diffamato va il suo maggio a presentà. A te in faccia il sole è un zero, 22 Chorus - Merry-making, joy, delight, pleasure, hunts, banquets, glasses of sparkling wine … Let everything show what happiness this joyous moment gives us, what pride so much honour arises in our merry souls! 23 Duke - Enough, friends; ah, your kind words are very appreciated! What blissful moments your affection gives me! If true friendship welcomes me within these walls I will be happy to enjoy the pleasures that it prepares to offer me. Ranuccio - Yes, it is with sincere friendship that we welcome you to this castle. Chorus - Loyal and sincere friendship! You are the joy of every heart. 24 Papaccione - (with exaggeration) Papaccione the Rascal, who never dodges his duties, bows his head to his magnificent Excellency, and comes to pay his homage to such a defamed man. Before you the sun is a zero, 47 è la luna una ciantella; sei dell’Orbico Emisfero la lucerna, no, anzi la stella: è il tuo core un mappamondo, la tua bocca un campo Eliso, sei bislungo, anzi rotondo, sei più bel del grande Acciso; che… cioè… ma mi confondo… di più dir non son capace… al silenzio mio loquace supplirà la tua bontà. Coro - Ah! Ah! Ah! Duca - Grazioso invero! Antonio - Compatite, è tutto zelo. Papaccione - (Del sublime mio pensiero stanno il merto ad ammirà!) 25 Argilla - Se un cor magnanimo tu chiudi in petto, dell’umil zingara soffri l’aspetto, che lieti auguri t’offre o signor. La gioja, il giubilo ti sieda allato, gli astri benefici, oltre l’usato, per te scintillino di alto splendor. Ghita/ Manuelitta - Gli astri benefici, ecc. Duca - Gli auguri accetto donna gentile, e ti prometto il mio favor. Papaccione - (Ma vi sta zingara come se nficca! Che mutria celebre! Che franco umor!) Ranuccio - Là sulle stanze andiamo, siegui i miei passi, amico. Duca - Guidami a tuo piacere: son tuo seguace ognor. 26 La nostra gioia accresca la rimembranza amica dell’amicizia antica, che strinse il nostro cor. Ranuccio - (Oh trista rimembranza! and the moon a ring-shaped cake; of the earthly hemisphere you’re the lantern, or better, the star: your heart is a globe, your mouth the Elysian fields, with your oblong, or rather, roundish shape you’re handsomer than an ugly man; and… what I mean is… I’m all confused… I cannot find the words… your goodness will make up for my eloquent silence. Chorus - Ha! Ha! Ha! Duke - Nice indeed! Antonio - Forgive him, he’s full of zeal. Papaccione - (They all stand in admiration before my sublime mind!) 25 Argilla - If a generous heart beats in your breast , bear the presence of this gypsy, who wishes you the best of happiness, my lord. May joy and bliss sit at your side, may the beneficial stars shine on you brighter than ever. Ghita/ Manuelitta - May the beneficial stars, etc. Duke - I accept your wishes kind woman, and I promise you my favour. Papaccione - (Goodness this gypsy how sneaky she is! What a woman! How outspoken!) Ranuccio - Let’s go to your apartments, follow me, my friend. Duke - Lead the way: I will follow you. 26 My happiness is increased by the fond memory of our long-standing friendship, which still binds our hearts. Ranuccio - (Oh woeful memory! 48 I torti miei rammento, e frenar posso a stento l’ascoso mio furor). Argilla - (L’alma perversa, e ria medita un tradimento; la vigilanza mia farà svanirlo or or). Antonio - (Sì trista rimembranza i torti suoi rammenta, mentre amistade ostenta più pasce il suo livor). Papaccione - (Me pareno mille anne, che notte va scuranno, che doppie, attà d’aguanno!) Saraggio un gran signor). Ghita/ Manuelitta/ Coro - Per voi risplenda il sole sgombro da nembo, o velo benigni influssi il Cielo a voi conceda amor. Di dolci flauti al suono, nel brio di sì bel giorno gioja respiri intorno, lungi tristezza, orror. Andiamo, andiamo. Tutto il corteggio si avvia agli appartamenti. Si cala il sipario. It brings to mind the wrongs I suffered and I can hardly curb my hidden fury). Argilla - (His evil, wicked soul plans a betrayal; but my vigilance will thwart it). Antonio - (The woeful memory reminds him of the wrongs he suffered, he shows friendship, but nourishes hatred). Papaccione - (It seems to me that it will be ages before night falls, what a good haul this year! I will be a lord). Ghita/ Manuelitta/ Chorus - May the sun shine on you, dispelling any clouds, may the heavens grant you their love and favours. At the sound of the sweet bagpipes, amidst the delights of such a joyful day, may happiness spread around and sadness and woe be far away. Let’s go, let’s go. They all leave towards the apartments. The curtain falls. 49 ATTO SECONDO ACT TWO Scena Prima Parte remota del castello; un muro attraversa la scena; in mezzo, cancello; a sinistra una porta ferrata; altra porta a dritta, che per una scala segreta conduce all’appartamento destinato al Duca di Alziras; in fondo una vecchia cisterna. È vicina la notte. S’introducono dal cancello Fernando e Sguiglio. Scene I A remote wing of the castle; a wall stands across the scene; in the middle, a gate; on the left, an iron door; on the right, another door behind which a secret stairway leads to the apartments of the Duke of Alziras; in the back, an old cistern. Night is falling. Fernando and Sguiglio, from the gate. 1 Sguiglio - Addò mmalora la trovo? Chella squaglia comme a Sautanasso; ma ‘ndo s’è nficcata? Fernando - Sguiglio, che succede? Sguiglio - Signò, la zingara, essa proprio mperzona m’ha ditto, ca l’aspettate ccà, ca v’ha da parlà de cose toste, e pesante. Io l’aje ditto, zingarè, Dillo a me, ca io, e lo patrone simmo una cosa, m’ha sonato no scozzetto accosì secante, che m’ha fatto vedè la luna dinto a lo puzzo. Fernando - Lascia fare alla sorte. Vanne. (Esce per lo cancello). 1 Sguiglio - Where the hell will I find her? She vanishes like a ghost; where on earth is she? Fernando - Sguiglio, what’s happening? Sguiglio - Master, the gypsy, she herself, in person, told me that you must wait for her here, for she has to speak to you about some important business. I said: gypsy, you can tell me, for my master and I are like one; but she lead me such a merry dance that I ended up believing that the moon is made of green cheese. Fernando - Leave it to fate. Go. (He leaves by the gate). Scena II Fernando, indi Ines. Scene II Fernando, then Ines. Ines - Eccolo! Amelia dice di non fidarmi di te. Fernando - Ah! Maledetta! Qando saprà chi è Fernando… Ines - E allora dillo, dimmi: chi sei? 2 Fernando - Lascia, che io taccia, e miglior tempo attendi. Ines - Va ingrato! Va! Temi di me? Non sai, Che arcani Amor non ha? Fernando - Legge crudele Ines - There he is! Amelia tells me that I should not trust you. Fernando - Ah! Unfair woman! When she will know who Fernando is… Ines - Speak, then, tell me who you are! 2 Fernando - Allow me to keep silent, and wait for better times. Ines - Leave, ungrateful man! Go! Don’t you trust me? Don’t you know that Love has no secrets? Fernando - A cruel circumstance 50 Il mio silenzio impone. Ines - Ah! No, crudele E mi lusinga il tuo fallace inganno. Fernando - (Hai più angosce per me fato tiranno?) 3 Un mentitor mi credi? Puoi dubitar di me? Aprimi il core, e vedi Se pura è la mia fè. Ines - Pensa, che i giorni miei Serbai finor per te: Che di dolor morrei Priva di tua mercè. Fernando - Un dubbio tal mi offende… Ines - Narra le tue vicende. Fernando - Per or nol posso… in breve Tutto saprai: tel giura Il labbro mio… Ines - Sicura Dunque sarò? Ah, temo Essere da te tradita. Fernando - Qual tema? Ah no… mia vita! Mirar quei vaghi rai, Ed esser mancatore Possibile non è. Ines - Perdona, io ti oltraggiai, Ma colpa fu di Amore, Che dubitar mi fè. 4 Fernando/ Ines - Se è ver, che in Ciel si formano I tuoi legami, o Imene, Eterne, indissolubili Tu rendi le catene, Che i nostri cori avvinsero, Che strinse il Nume arcier! Ines - Addio! Fernando - Va pur, mia vita… Ti affida, e non temer. forces me to keep quiet. Ines - Ah! No, you cruel man, you just flatter me with deceptive lies. Fernando - (Have you any more tortures in store for me, dreadful fate?) 3 Do you think me a liar? Can you doubt me? Tear my heart open, and see if my faith is pure. Ines - Know that I’ve spent all my days thinking of you: That I would die of grief without your love. Fernando - Your doubts offend me… Ines - Tell me your story. Fernando - Not just yet… soon you’ll know everything: I swear… Ines - Can I then rest assured? Ah, I fear that you’ll betray me. Fernando - Betray you? Ah never… my life! To look into your eyes and lie to you is impossible. Ines - Forgive me, I’ve offended you, but it was Love’s fault, he made me waver. 4 Fernando/ Ines - If it is true that your bonds, Hymen, are knotted in heaven, do make these ties, with which Cupid entwined our hearts, eternal, indissoluble! Ines - Farewell! Fernando - Go, my beloved… have trust, have no fear. 51 Affetti! Ah! Voi, che ognore Quest’anima straziate, L’istante non turbate Di un rapido piacer! Ines - Affetti! Ah! Voi, che ognore Quest’anima straziate, L’istante non turbate Di un rapido piacer! Sicura dunque sarò. (Via Ines). Emotions! ah! you that tear this soul apart, do not cloud this instant of swift pleasure! Ines - Emotions! ah! you that are tearing this soul apart, do not cloud this instant of swift pleasure! Then I shall be trustful. (Ines leaves). Scena III Fernando, indi Argilla dal cancello. Scene III Fernando, then Argilla from the gate. 5 Argilla - Fernando? Fernando - Argilla, che hai da dirmi? Argilla - Ascoltate: qui si ordisce un tradimento, forse un assassinio … il perfido Ranuccio ha scambiato la mano di sua figlia con la vita del Duca. Fernando - Spiegati! Argilla - Vi prescelgo a sorprendere l’aggressore: Don Antonio, che compirà il misfatto questa notte stessa. Avete delle armi? Fernando - Questa. (Mostrando un pugnale) Argilla - Presto, nascondetevi, e siate pronto ad accorrere alla mia voce. 5 Argilla - Fernando? Fernando - Argilla, what is it you must tell me? Argilla - Listen:a betrayal has been planned, perhaps a murder … the wicked Ranuccio has traded the hand of his daughter with the life of the Duke. Fernando - Explain yourself better. Argilla - I choose you as the man who will catch the assassin: Don Antonio, who will commit the crime this very night. Have you any arms? Fernando - This one. (Showing her a dagger) Argilla - Hide yourself then, and stand ready to run when I call you. Scena IV Argilla, indi dal cancello Sguiglio, e zingari seguaci di Argilla, con torce smorzate, un lanternino, e catene. Scene IV Argilla, then from the gate Sguiglio, and Argilla’s gypsies carrying shaded torches, a small lantern and chains. Argilla - Venite amici. Sguiglio - Aje trovato lo patrone mio? Argilla - Come, friends. Sguiglio - Have you found my master? 52 Argilla - Sì. Sguiglio - L’aje parlato? Argilla - Già. Sguiglio - E mo addò stà? Argilla - In un sito sicuramente. Sguiglio - M’aje levata la curiosità! L’aje ditto, ca m’aje trattenuto cottico, pe t’ajutà a la mbroglia? Argilla - Non ti preoccupare, lo avvertirò di tutto fra poco: intanto prepariamoci a scendere. Si dia adesso il segno al credulo Papaccione. (Batte la porta ferrata) Papaccione! Papaccione! Argilla - Yes. Sguiglio - Have you talked to him? Argilla - Certainly. Sguiglio - And where is he now? Argilla - Somewhere. Sguiglio - You’ve really satisfied my curiosity! Have you told him that you asked me to stay and help you out with this swindle of yours? Argilla - Don’t worry, soon I will tell him everything: meanwhile get ready to lower yourselves. And now let’s give that dupe of Papaccione the sign. (She knocks on the iron door) Hey, Papaccione! Scena V Papaccione prima dentro, poi fuori dalla porta ferrata, e detta. Scene V Papaccione, first inside and then outside the iron door, and the above. Papaccione - Ma si non sento primma cantà lo gufo, e la cevetta, comme vuò che te apro? Argilla - (Oh maledetto! Al riparo). Allora, apri. Quante civette vuoi sentire? Papaccione - Ne? E tu che sì cevettola? Argilla - Non sai che zingara e civetta sono la stessa cosa? Fuori, avanti, fuori! Papaccione - Mo… quanto nzerro sta porta, e so cottico. (Chiude la porta, e mette le chiavi alla cintura). Argilla - (Quelle chiavi saranno presto in mano mia). Papaccione - Argì… aggio portato porzì sto sacco pe me ne carrià quante chiù ne pozzo de zecchine. Argilla - Benissimo: andiamo. Papaccione - Dico io… è proprio necessario che devo scennere llà bascio? Argilla - Da solo. Papaccione - Ma pecchè non scenimmo nziemo? Argilla - Papaccione! Ti ho spiegato che quelle ric- Papaccione - If the owl and the little owl have not sung, how do you expect me to open the door? Argilla - (Damn him! I must make something up). Open up. How many little owls must you hear? Papaccione - What? Are you a little owl? Argilla - Don’t you know that little owl and gypsy mean the same? Out, come on! Papaccione - Here… let me lock this door, and I’ll be with you. (He locks the door and attaches the keys to his belt). Argilla - (Those keys will soon be in my possession). Papaccione - Argilla… I’ve brought this bag, so that I can carry away with me as many sequins as I can. Argilla - Excellent: let’s go. Papaccione - Tell me… is it really necessary for me to go down there? Argilla - Alone. Papaccione - Why don’t we go down together? Argilla - Papaccione! I’ve already explained that 53 chezze son destinate a te solo. Papaccione - Aspè… sapisse almenno comme stanno d’umore chille duje signore, Giuditta e Loferne... Sodoma e Gomorra, comme se chiammano? Argilla - Sì, Giuditta e Loferne... Sodoma e Gomorra... Astarotte, e Belzebucco! Li ho pacificati co’ miei scongiuri: (si affaccia alla cisterna) Oh! Voi, custodi di questa cisterna, fate sentire al buon Papaccione gli ordini dei numi Infernali! (Si vede dal fondo della cisterna una vampa, indi si sente il seguente coro sotterraneo) 6 Coro - Scendi, scendi Papaccion, Tanto caro al dio Pluton! Di monete un milion Generoso ei t’offre in don: Scendi, scendi Papaccion, Tanto caro al dio Pluton! 7 Papaccione - (Che brutte vuce llà bascio!) Argilla - Bada però di non portare indosso alcun metallo. Papaccione - E quale metallo? Argilla - Per non rovinare la tua sorte! Qualsiasi tipo di metallo… anelli, orecchini, cinture, spade, armi, coltelli... chiavi! Papaccione - Tengo chelle della porta, e de le catene de lo prigioniero. Argilla - Benissimo, lasciale a me: vai, vai, sù, vai... 8 Papaccione - Mo! Aspetta, e bì che pressa! Scenno, gnorsì, bel bello! Ma all’infernal drapello, Primma che me presento, Vorria no complimento Cottico combinà. Argilla - Poltrone! Ogni momento Caro ti costerà. Papaccione - Si vada quanno è chesto… only you are entitled to the treasure. Papaccione - Wait…if at least I knew in what mood those two ladies are... what are they called, Giuditta and Loferne, Sodom and Gomorrah? Argilla - Giuditta and Loferne, Sodom and Gomorrah! It’s Astarotte and Beelzebub! I soothed them with my charms: (leaning over the cistern) Hey! You who guard the immense riches hidden in this cistern, let our good Papaccione hear the orders of the Infernal gods! (A burst of flame rises from the bottom of the cistern, then the following chorus is heard) 6 Chorus - Come down, Papaccione, Pluto’s darling! The god generously offers you millions of gold coins: Come down, Papaccione, Pluto’s darling! 7 Papaccione - (Alas! What ugly voices!) Argilla - I warn you, though, don’t carry with you any metal Papaccione - What metal? Argilla - It would bring you bad luck! I mean any kind of metal… rings, ear-rings, belt buckles, swords, daggers, knives... keys! Papaccione - I’ve got the keys of the door and of the prisoner’s chains. Argilla - Leave them with me: off you go now… 8 Papaccione - Now! Wait, what hurry! I’ll go down, all right, here I go! But before I show up in front of the infernal pair, I must think of something flattering to say to them. Argilla - Lazybones! You’ll pay dearly for every moment you waste. Papaccione - If that’s so I must go… 54 Gnernò! Non è paura… Ma è un venticello infesto, Na meza tramontana, Che addosso na terzana M’ha fatto mo scetà. Addio: di doppie o cara Portà te voglio un carro… Ma dimme, no catarro Ce potarria piglià? Argilla - Orsù men vo… tu resta… Papaccione - Ah no mio ben, ti arresta! Mo scenno… eccome ccà! (Un’altra vampa dalla cisterna). Misericordia! Ajemmè! Dimme Sta fiamma de che sa? Argilla - Sdegnato si è Plutone, Il devi ora placar. Papaccione - Gnernò… lui m’è patrone… Mo veo de lo placà… Per quei magnifici Raggi frontiferi, Che di Proserpina Fur doni egregi, Plutone! Ah, placati Per carità! Coro - No no! Papaccione - Se di olocausti Hai desiderio, Offro sta zingara, Sto bello intingolo Alla tua cognita Golosità. Coro come sopra - Là fra tartarei Chiostri, terribili Discese rapida Tua voce flebile: Pluto dimentica It’s not that I’m afraid… not at all! It’s that a nasty breeze, some kind of north wind, has made me catch the tertian fever. Farewell: darling, I’ll bring you a cartload of coins … but, tell me, is there any risk that I’ll get a lung congestion? Argilla – All right, I’ll go… you stay… Papaccione - Ah, no, my darling, wait! I’m going down… here I go! (Another burst of flame from the cistern). My goodness! Poor me! What’s this flame all about? Argilla - Pluto’s got angry, now you must sooth him. Papaccione - Alas… he is my master… I’ll try to assuage him… For those magnificent frontal rays, which were Proserpina’s distinguished gifts, Pluto! Ah, relax, for goodness sake! Chorus - No, no! Papaccione - If you’re in the mood for a little sacrifice, let me offer your knowledgeable palate this gypsy, this tasty morsel. Chorus as above - All through the ghastly, infernal cloisters your begging voice has spread and bounced: Pluto’s forgotten 55 Antiche ingiurie, E la sua grazia Ti sa tornar. Ma ogni altro indugio Lo fa sdegnar. Argilla - Orsù risolviti. Papaccione - N’aggio timore… N’eroe divento… animo, e core! (Ma vi ste gamme comme so toste, Che sempre arreto vonno cessà!) Sguiglio - (Dalla cisterna) Scendi. Papaccione - Chi parla? Argilla - È un diavoletto. Sguiglio - Scendi… Papaccione - Mo vengo… Sguiglio - Presto. Papaccione - Mo vengo, Eccomi cca… Ma vi sto spireto comm’è afflittivo! Ma vi che susta me stace a dda! Dà cca lo parpeto m’arresta, e azzoppa, Llà co le ddoppie vorria fa toppa, E in così barbaro conflitto isterico Chi me consiglia che aggio da fa? Addio… mia bella!… Si torno vivo Maje cchiù co spirete voglio trattà! (Scende nella cisterna e poco dopo si ode il rumore di Papaccione che viene fatto ruzzolare giù per le scale). Argilla - Pietoso Cielo! Deh tu guida i miei passi. (Apre la porta ferrata ed entra sollecitamente). Papaccione - (Dal fondo della cisterna) Ajuto Argilla, ca ccà m’hanno stutata la lanterna! Sguiglio - (Con voce finta) Rompiti il collo! All’inferno! Papaccione - Misericordia! Ca chiste me carreano a casa cauda! your past offences and once again grants you his favour. But any further delay will provoke his wrath. Argilla - Go then, once and for all. Papaccione - I’m terrified… Courage… I’ll become a hero! (Goodness, what stubborn legs I have, they want to walk only backwards!) Sguiglio - (From the cistern) Come down. Papaccione - Who’s speaking? Argilla - It’s a little devil. Sguiglio - Come down… Papaccione - I’m coming… Sguiglio - Hurry up. Papaccione - I’m coming, here I am… What a nuisance this spirit is! What pressure he puts on me! On the one hand fear stops me and lames me, on the other I want to make a dive for the money: and in such a painful, hysterical struggle who will advise me what to do? Farewell… my beauty! If I come back alive I’ll never have anything to do with spirits any more! (He lowers himself into the cistern and soon a great noise is heard, as the gypsy’s followers trip Papaccione and make him roll down the stairs). Argilla - Merciful heaven! Do guide my steps. (She unlocks the iron door and hurries in). Papaccione - (From the bottom of the cistern) Help, Argilla, they put out my lantern! Sguiglio - (Disguising his voice) Break your neck! Go to hell! Papaccione - Goodness gracious! They are going to throw me right into the cauldron! 56 Sguiglio - Ascimmo priesto, primma che chillo non se sose da lo smallazzo, che l’avimmo fatto pigliare. (Uscendo con gli zingari dalla cisterna). Sguiglio - Out, quick, before he recovers from the tumble we made him take. (He emerges from the cistern with the gypsies). Scena VI Argilla conduce fuora Don Sebastiano, indi Papaccione dalla cisterna, poi Ranuccio, ed Antonio, Fernando in osservazione. Scene VI Argilla leading Sebastiano out, then Papaccione from the cistern, then Ranuccio, and Antonio, Fernando on the lookout. 9 Argilla - Non c’è tempo da perdere! (A zingari nascosti, che corrono alla voce di Argilla). Sguiglio - Zingaré: pronto e servito! L’amico sta llà bascio… io me ne torno da lo patrone mio. Argilla - No… vai da Ines e dille di stare in guardia: temo che il padre la voglia fare sposare ad Antonio questa notte. Sguiglio - Nzomma tu aje pigliato a forza de mira a sto povero cuorio mio? Papaccione - M’hai fatto chesto Zingara mmalorata! (Papaccione arrampicandosi, e tremando giunge sopra della cisterna). Mo moro! Chi m’ajuta a bottà le gamme? Addò sta chella gatta morta, chella mpesa, che m’ha fatto avè sto bello complimento? (Si avvicina alla porta, e si sorprende nel ritrovarla aperta). Oh! Maro me! La porta è aperta? Ah quacch’auto guajo chiù gruosso me sta stipato! Mannaggia lo tesoro, e quanno maje ce n’è stata parola! (Entra nella porta). (Arriva Don Ranuccio, ed Antonio avvolto in un tabarro). Ranuccio - Antonio, vieni! Il Duca dorme e nulla si frapporrà ai nostri piani. Vai! (Apre la porta indicata). Argilla - (Andate Don Fernando… prevenite il traditore!) (Sulle punte de’ piedi Fernando attraversa la scena, 9 Argilla - There is no time to waste! (To some hidden gypsies, who come out at Argilla’s voice). Sguiglio - Gypsy, you’re served! Your friend is down there… I’m going back to my master. Argilla - Wait… you must go to Ines and tell her to be on her guard: I fear that tonight her father will force her to marry Antonio. Sguiglio - You have really decided to abuse this poor heart of mine, haven’t you? Papaccione - Damn gypsy, you played a nasty trick on me! (Papaccione, shaking, climbs up and emerges from the cistern). I’m dying! Someone help me throw my legs out! Where is that lady scoundrel who played me such a dirty trick? (He goes to the door and, to his surprise, finds it open). Oh! Poor me! The door is open! Alas, some even bigger trouble awaits me! Damn the treasure and the moment I was told about it! (He goes through the door). (Enter Don Ranuccio and Antonio, wrapped in a cloak). Ranuccio - Come, Antonio. The Duke is asleep and nothing will hinder our plan. Go! (He opens the door) Argilla - (Go Don Fernando... stop the traitor!) (Fernando tiptoes across the stage and goes 57 e s’introduce nella porta suddetta). through the door). Scena VII Ranuccio, Antonio esce frettoloso, ed inseguito da Fernando, indi dalla porta istessa il Duca di Alziras senza manto e con ferro impugnato, poi Papaccione dalla sua porta. Amelia che trascina Sguiglio, infine Argilla, che conduce Don Sebastiano. Scene VII Ranuccio, Antonio running out, chased by Fernando, then from the same door the Duke of Alziras warting a cloak and brandishing his sword, then Papaccione from his door. Amelia dragging Sguiglio, and finally Argilla, leading Don Sebastiano. Ranuccio - (al Duca) Che succede? Duca - Un grido … veggo il braccio... un uomo che io non ravviso lo arresta, lo insegue… chiamo i miei servi, ma è già sparito … Papaccione - (Ah! La zingara me l’ha fatta! Lo prigioniero se n’è fojuto!) Argilla - Don Sebastiano! Ranuccio - (Alvarez!) Papaccione - (È tornato! Oh che galantommo!) 10 Ranuccio - (Oh colpo! Io fui tradito!) Duca - Ah… parmi… (stentando a riconoscerlo) Sebastiano - Non sai tu ravvisarmi? Duca - Alvarez! Non m’inganno. Oh qual ti miro! Ranuccio - (Oh, colpo! Ahimè!) Papaccione - (Ajemmè!) Ranuccio - (Oh come a danni miei Par che congiuri il fato! Lena e vigor perdei… Coraggio io più non ho!) Duca/ Amelia - (Oh quante un solo istante Strane vicende aduna Incerto/a, e palpitante Che immaginar non so!) Argilla/ Sebastiano (In quel pallor d’indegno Ranuccio - (To the Duke) What’s happening? Duke - A shout woke me up… I saw an arm raised against me... a man stopped him, chased after him... I called for my servants, but he had disappeared… Papaccione - (Ah! The gypsy has tricked me! The old man has escaped!) Argilla - Don Sebastiano! Ranuccio - (Alvarez!) Papaccione - (He’s come back! What a gentleman!) 10 Ranuccio - (Alas! I’ve been betrayed!) Duke - Ah… you look like… (finding it hard to recognise him) Sebastiano - Don’t you recognise me? Duke - Alvarez! I am not mistaken. Oh, what a surprise! Ranuccio - (Ah, what a blow! Woe is me!) Papaccione - (Poor me!) Ranuccio - (Ah! Fate seems to work against me! I’ve lost all my strength… I have no more courage!) Duke/ Amelia - (How many strange events are happening in a single moment, I feel hesitant and fearful, I could have never imagined this!) Argilla/ Sebastiano (That unworthy man’s pallor 58 Palesa il fier conflitto, Che il grave suo delitto Nel sen già gli destò!) Papaccione - (Oh! Carne prelibbate! Ciacelle sbenturate! De vuje mo Don Ranuccio Ne fa no fricandò!) Sguiglio - (Ebbiva la siè Argilla! Se mpizza comme anguilla! Vedimmo sta faccenna Comme se sbroglia mo!) Duca - (A Sebastiano) Ma come qui sei? Sebastiano - Tel dica costui… (indicando Papaccione) Duca - Tu dunque… Argilla - Colui Parlare non può. Per ora il silenzio Succeda al rumore: Che tutto, signore, Svelarti saprò. 11 Ranuccio - (Mi straziano il petto Furore, e dispetto! Da palpiti oppressa Confusa, avvilita Quest’alma smarrita Consiglio non ha!) Argilla/ Sebastiano - (Gli straziano il petto Timore, e dispetto: Da palpiti oppressa Confusa, avvilita, Quest’alma smarrita Consiglio non ha!) Gli altri - (Mi desta ogni oggetto Un forte sospetto! Da palpiti oppressa, reveals the fierce conflict that his serious crime has aroused in his breast!) Papaccione - (Oh! Delicious chops! unfortunate meatballs! Now Don Ranuccio will cook you over a low flame!) Sguiglio - (Hurrah for the lady Argilla! She’s as sly as a fox! Let’s see now how this skein unravels!) Duke - (To Sebastiano) How do you happen to be here? Sebastiano - This man will tell you. (pointing to Papaccione) Duke - Then it was you… Argilla - He cannot speak. Let silence follow the uproar: I will tell you everything. 11 Ranuccio - (Fury and vexation are tearing my heart! Oppressed by anguish, confused, discouraged, this soul is at a loss, knows not what to do!) Argilla/ Sebastiano - (Fear and vexation are tearing his heart Oppressed by anguish, confused, discouraged, this soul is at a loss, knows not what to do!) The others - (All this arouses in me a strong suspicion! Oppressed by anguish, 59 Dubbiosa, avvilita, Quest’alma smarrita Consiglio non ha!) (Viano per diverse parti). confused, discouraged, this soul is at a loss, knows not what to do!) (They all leave in different directions). Scena VIII Sala di armi nel castello. Ines, poi Ranuccio, e Papaccione. Scene VIII The castle’s armoury. Ines, then Ranuccio, and Papaccione. 12 Ranuccio - Disgraziato! Come hai potuto... Papaccione - Signò! Stammoce cojeto co le mmane, e parlammo da galantuommene! Ranuccio - Aprir la porta! Maledetto! Papaccione - Io aprir la porta? Ma prima d’aprì na porta, io ce penso diece mila bote! Ranuccio - E le chiavi? Papaccione - E le chiavi... a zingara se le pigliaje. Ranuccio - E perché gliele hai date? Papaccione - E pecchè, pecchè ... se le pigliaje! Ranuccio - No… tu ti sei messo d’accordo col prigioniero! Papaccione - Io, co lo prigioniero! Ma se quello è andato a farse na passatiella pe lo fatto sojo! Ranuccio - Ah perfido! (Volendo snudare il ferro contro Papaccione: Ines si fa avanti, e lo trattiene). Ines - Fermatevi… Papaccione - Sarva! Sarva! (Via). Ines - Ma cosa ti fece quel povero Papaccione? Ranuccio - In quanto a te: preparati a partire per Toledo, dove affari importantissimi mi reclamano e là tu porgerai la mano ad Antonio Alvarez. Ines - Antonio non sarà mai mio consorte. Ranuccio - Come osi rispondermi con tanta sfrontatezza? Ines - Il mio cuore è già promesso a Fernando. 12 Ranuccio - Rascal! How could you... Papaccione - Master! Let’s keep our hands to ourselves and behave like true gentlemen. Ranuccio - Unlock the prison! Damn you! Papaccione - I, unlock the prison! If I think twice before I even open a door! Ranuccio - But the keys...? Papaccione - The keys... the gypsy took them. Ranuccio - Why did you give them to her? Papaccione - I didn’t… she just took them! Ranuccio - I don’t believe you: you must have been in league with the prisoner! Papaccione - In league! If he went for a stroll he did it of his own free will! Ranuccio - Ah, rogue! (He makes as if to draw his sword: Ines comes forward and stops him). Ines - Wait… Papaccione - I’m saved! (He leaves). Ines - What has poor Papaccione done to you? Ranuccio - As for you, prepare to leave for Toledo… a very important business calls me there and you will marry Antonio Alvarez. Ines - Antonio will never be my husband. Ranuccio - How dare you answer back in such shameful fashion? Ines - I am engaged to Fernando. 60 Ranuccio - A Fernando? E chi è questo Fernando? Ines - Un giovane degno dei miei affetti. Ranuccio - Sciagurata, meriti soltanto l’ira di un padre tradito. Farai quello che ormai è già deciso! Ranuccio - To Fernando? Who is this Fernando? Ines - A young man worthy of my love. Ranuccio - Wicked woman, all you deserve is your father’s wrath. You’ll do as I tell you. Scena IX Duca di Alziras, Don Sebastiano. Scene IX The Duke of Alziras, Don Sebastiano. Duca - Mille dubbi agitano la mia mente! Uno solo, che io resi infelice, avrebbe giustamente potuto vibrarmi il fulmine della sua vendetta: mi si fece credere che il mio sventurato fratello insidiasse i miei giorni. Ora che i suoi calunniatori mi hanno svelato la sua innocenza, non so dove rintracciarlo... Sebastiano - Duca, non ravvisasti il giovane che arrestò la mano del tuo assassino? Duca - Oh quanto amerei conoscerlo! Duke - A thousand doubts toss in my mind! Only one person, whom I wronged, could have rightly vented his wrath against me: I was made to believe that my poor brother plotted against me. Now that his slanderers have revealed his innocence, I don’t know where to find him... Sebastiano - Have you not recognised the young man who stopped the hand of your assailant? Duke - Oh, how I would like to know who he is! Scena X Sebastiano, Fernando ed il duca di Alziras. Scene X Sebastiano, Fernando and the Duke of Alziras. 13 Sebastiano - Miralo: è il tuo germano, E’ quel Fernando istesso, Che tu volesti oppresso, Che i giorni tuoi salvò. Duca - (Ah! Qual sorpresa è questa! Mirarlo, oh Dio! Non oso! Ei tanto generoso Le offese mio scordò?) Fernando - Mai questo cor restio Fu di natura al grido E sparse ognor di obblio Gli oltraggi che provò. Duca - I torti miei ravviso, Son di perdono indegno… 13 Sebastiano – Look at him: it is your brother, it is that same Fernando oppressed by you who’s saved your life. Duke – (Ah! What a surprise! Heavens, I dare not meet his eyes! Could he so generously forgive my crime?) Fernando - My heart was never reluctant to heed nature’s voice and has always covered in oblivion the affronts it suffered. Duke - I recognise my wrongdoing, I am unworthy of your forgiveness… 61 Fernando - Sia questo amplesso un segno Che mi sei caro ancor. Sebastiano - Sia quest’amplesso un segno Che gli sei caro ancor, Del suo sincero amor. 14 Sebastiano, Duca e Fernando E’ tenero il pianto, Che il ciglio m’inonda! Natura ne ha il vanto, Nol preme il dolor. Ma dopo il conflitto Di fiera procella Oh! Quanto è mai bella La pace del cor! 15 Duca - Ma dimmi… e da qual mano L’insidia a me fu tesa? Fernando - Lo ignoro… Sebastiano - Ah! Sì, Io non m’inganno Fosti dal rio tiranno, Dal mio persecutor. Duca - Che? Da Ranuccio? Oh, quale Idea mi sorge in mente! Ed invido, e fremente Seppe dolersi un dì, Che il mio sovran clemente Nel primo onor di corte A lui mi preferì. Sebastiano - Perciò di trarti a morte Trama fatal ti ordì. Duca - Se laccio tal mi tende, Paventi ormai l’indegno: Il fulmin del mio sdegno Sul capo suo cadrà. Sebastiano - Ah, sì… quell’alma perfida Sempre alla strage è intenta: Ravvisa in me una vittima Fernando - Let this embrace be a sign of how much I still care for you. Sebastiano - Let his embrace be a sign of his affection, of his sincere love. 14 Sebastiano, Duke and Fernando Tender tears wet my eyes! They are nature’s victory, not a sign of sorrow. And after the turmoil of a fierce storm, oh, how much nicer is the peace of one’s heart! 15 Duke - But tell me… whose was the hand that set the trap for me? Fernando - I ignore that… Sebastiano - Ah! Yes, I am not mistaken, it was that wicked tyrant of my persecutor. Duke - What? Ranuccio? Oh, what suspicion arises in my mind! In the past he had reason to be envious and angry, disappointed that my generous king had chosen me for a high position at court. Sebastiano - And so he schemed a wicked plan to have you killed. Duke - If he laid such a snare for me, the unworthy man must tremble: the wrath of my fury will fall upon him. Sebastiano - Ah, yes… that wicked soul is always plotting scourge: I myself am a victim 62 Della sua crudeltà. Fernando - (Perché del mio tesoro Quel mostro è genitore? E fra dovere, e amore Che far mi converrà?) Duca, Sebastiano e Fernando – Sian grazie al ciel pietoso, Che nel fatal perielio Rivolse amico il ciglio, Ebbe di noi pietà. of his cruelty. Fernando - (Why has my beloved such a monster for a father? Between duty and love, what shall I do?) Duke, Sebastiano and Fernando Thanks be to the merciful heaven, which in the moment of fatal danger looked kindly upon us, had mercy on us. Scena ultima Tutti gli attori, come saranno indicati. Final Scene All the characters, as they are indicated. 16 Ranuccio - Eccellenza vengo a conoscere lo stato della vostra salute. Duca - (Ironico) Ve ne sono grato, e spero fra poco di darvi quella risposta che meritate. Ranuccio - (Ah son perduto!) Ines - Oh, Fernando! Il padre vuol farmi sposare Antonio. Ranuccio - Ah, questo sarebbe il famoso Fernando? Duca - Sì, mio fratello… riconoscetelo pure. Fernando - E questa, o germano, è la mia sospirata fiamma!… Argilla - Eccellenza! Abbiamo trovato Antonio Alvarez, nel vicino villaggio… Sì, vostro nipote, il ministro della vendetta di Ranuccio, che la notte scorsa avrebbe assassinato il Duca. Duca - Che sento! Sguiglio - (Oh! Guaje!) Papaccione - Altro che imbrogli da zingara! Duca - (A Ranuccio) Iniquo! Sulla tua fronte è già scolpito il marchio d’infamia: renderai conto dei tuoi misfatti. Papaccione - Comme vonno paré belle dinto a doje gajole le cape de Maledonato, e Malatesta? 16 Ranuccio - Your Excellency, I’ve come to enquire about the state of your health Duke - (Ironically) I appreciate your solicitude, and hope to give you soon the answer you deserve. Ranuccio - (Alas! I am lost!) Ines - Oh, my Fernando! My father wants me to marry Antonio. Ranuccio - So this would be the famous Fernando? Duke - Yes, and he’s my brother. Fernando - And this, brother, is my fair betrothed!… Argilla - Your Excellency! We have found Antonio Alvarez in the nearby village... Yes, your nephew, the minister of Ranuccio’s revenge, who, last night tried to kill the Duke. Duke - What do I hear! Sguiglio - (Oh! What a mix-up!) Papaccione - This is even better than the gypsy’s tricks! Duke - (To Ranuccio) Rogue! You are branded with infamy and you will have to answer for your crimes. Papaccione - Won’t they look nice, the faces of Baddie and Foulplay, behind bars? 63 Ranuccio - (Inginocchiandosi) Eccellenza, mi prostro supplice e pentito… Sebastiano - Alzati sciagurato! Duca, se la sola ingiuria da me sofferta arma il braccio della tua giustizia, io di fronte a voi e al cospetto di tutti gli offro il mio perdono… Duca - Sia confinato per sempre in questo castello, ove troverà supplizio ne’ suoi rimorsi. (Portano via Ranuccio) Sebastiano - Vieni fra le mie braccia, essere benefico e mia salvatrice! Tu farai le veci di quella figlia che perdei e che non posso cancellare dal mio cuore. Argilla - Vi sono grata e vi farò onore, perchè io stessa sono di una illustre famiglia: quella zingara che rispettai qual madre, mi confidò di avermi rapita bambina... Sebastiano - Qual somiglianza!.. Argilla - Conservo ancora questa gemma, che mi pendeva al collo quel giorno, quando fui tolta alle cure della mia poco accorta balia. Sebastiano - Cielo! Ecco le cifre del mio nome! Lascia ch’io baci la mia figlia smarrita! Sguiglio - E zingarè! Bì si pozzo trovà purìo non patre cavaliero! 17 Argilla - Tu l’autor de’ miei giorni? Io la tua figlia? Ah padre! Ah! Cari miei! Di tanta sorte Palpito incerta ancora! Amica alfin per me sorse l’aurora? 18 E fia ver? Di sì gran dono Fausto il Ciel mi ricolmò? Or comprendo i dolci moti, Quei soavi affetti ignoti, Che natura in me destò! 19 Sì! Mi stringi o padre al seno, E il tuo cor sia lieto appieno Se fin’ora sospirò. Ranuccio - (Kneeling down) Excellency, I kneel before you, pleading and regretful… Sebastiano - Get up, wicked man! Duke, if it is only the offence I suffered to arm the hand of your justice, before you and everybody here I grant him my forgiveness… Duke - Let him then be forever confined to this castle, remorse will be his punishment. (Ranuccio is carried away) Sebastiano - Come into my arms, kind being and my saviour! You will be the daughter I lost and whom I cannot forget. Argilla - I am grateful and I will do you honour, because I was born of an illustrious family: the gypsy I called mother told me that I was abducted as a child... Sebastiano - What a resemblance!.. Argilla - I still have this precious pendant, which I was wearing that day, when I was taken away from my careless nursemaid. Sebastiano - Heaven! Those are the initials of my name! Let me kiss my lost daughter! Sguiglio - Goodness gracious, gypsy, can’t you find a noble father for me too? 17 Argilla - You, the author of my days? I, your daughter? Ah father! Ah! My dear ones! Such good fortune makes my heart throb! Has a friendly dawn finally risen for me? 18 Can it be true? Has merciful Heaven granted me such a great gift? Now I understand the tender impulses, the mysterious, gentle affection that nature had arisen in me! 19 Ah! Father, embrace me, and let your heart, which to this day has suffered, rejoice! 64 Sebastiano - Sì ti stringo, o figlia al seno, E il mio cor sia lieto appieno Se fin’ora sospirò. Coro - Stringi pur la figlia al seno E il tuo cor sia lieto appieno Se fin’ora sospirò. Sguiglio - (Al Duca) Orsù fra li contiente, Fra abballe, e fra festine, Vedimmo un po’ li diente, Signò, d’esercità. Papaccione - (Ad Argilla) Contesa, mo si fatta Pe me non sì cchiù cosa… Co Ghitta, chè porposa, Mo veo de m’acconcià. Argilla - Padre… Sebastiano - Figlia… Argilla - L’eccesso del contento Mi toglie… oh Dio! l’accento! Piacere incomprensibile L’alma beando va! Oh! gioia inesprimibile! Oh mia felicità! 20 Ah! Dopo il fiero nembo, Che ha l’anima agitata, Oh! quanto sei più grata, Dolce serenità! Sebastiano - Ah! Dopo il fiero nembo, Che ha l’anima agitata, Oh! quanto sei più grata, Dolce serenità! Gli altri - Ah! Dopo il fiero nembo, Che ha l’anima agitata, Oh! quanto sei più grata, Dolce serenità! Coro - Godiam di sì bel giorno La bella ilarità! Sebastiano - Daughter, I embrace you, and my heart, which to this day has suffered, will now rejoice! Chorus - Embrace your daughter, and let your heart, which to this day has suffered, rejoice! Sguiglio - (To the Duke) Let’s now be happy, and while we dance and toast let’s make sure, gentlemen, that we also exercise our teeth a little. Papaccione - (To Argilla) Now that you’re a noblewoman you’re no longer for me… Ghitta will do, she’s nice and round. Argilla - Father… Sebastiano - Daughter… Argilla - My happiness is so great that words… oh God! fail me! Unfathomable pleasure fills my soul! Oh! Inexpressible joy! Oh happiness! 20 After the dark clouds that loomed over me, oh! how much more welcome you are, sweet serenity! Sebastiano - Ah! After the dark clouds that loomed over me, oh! how much more welcome you are, sweet serenity! The others - Ah! After the dark clouds that loomed over our souls, oh! how much more welcome you are, sweet serenity! Chorus - In this fine day let us enjoy our carefree cheerfulness! 65 Orchestra Internazionale d’Italia First Violins: Alessandro Cervo*, Alessio Andreozzi, Anna Julia Badia, Jozek Cardas, Domenico Castro, Dmitri Chichlov, Daniel Manasi, Ariel Sarduy, Sara Scalabrelli, Daniela Stancu Second Violins: John Maida*, Carlo Coppola, Viviana Di Carli, Rita Iacobelli, Georgica Lecteroglu, Flavio Maddonni, Katrzyna Osinska, Silvana Pomarico Violas: Giorgio Gerin*, Stefania Di Biase, Fanny Forcucci, Alberto Pollesel, Marius Suarasan Cellos: Alexandra Gutu*, Andrea Crisante, Giuseppe Grassi, Vanessa Petrò, Rasvan Suma Double bass: Fabio Serafini*, Luigi Lamberti, Alberto Lo Gatto Flutes: Federica Bacchi*, Alessandro Muolo Oboes: Alessandro Staiano*, Peter Fazekas Clarinets: Massimo Mazzone*, Paolo Turino Bassoons: Massimo Data*, Deborah Luciani Horns: Gianni D’Aprile*, Giovanni Pompeo Trumpets: Marco Nesi*, Ray Novak Trombones: John Eherbeek*, Yossi Itskovich, Marcello Dabanda Conductor: Arnold Bosman * solos Coro da Camera di Bratislava Sopranos: Helga Bachová, Helena Hanzelova, Milada Macháková, Katarina Majerníková, Henrieta Palkovicova, Alena Pradlovska, Jarmila Pufflerova, Katarina Serešová Altos: Gizela Burska, Eva Katrenchinová, Margot Kobzova, Anna Kováchová, Zuzana Limpárová, Eva Matiasovska, Elena Matusova, Lucia Molnarova Tenors: Pavol Dvoran, Juraj Durco, Valter Mikus, Juraj Nociar, Jan Prazienka, Lubos Straka, Ladislav Velky, Stanislav Vozaf, Frantisek Urcikan Baritones/Basses: Peter Hlbocký, Leo Krupa, Ivan Kudlik, Ladislav Méry, Milan Mikulasovych, Maros Mosny, Jan Procházka, Pavol Šuška, Matúš Trávnichek, Peter Trnka 67