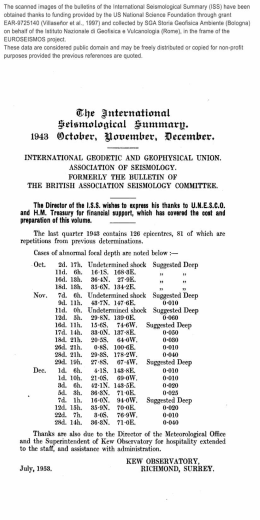

SESSIONE 2.3 GNGTS 2011 NUOVI STRUMENTI PER LA VALUTAZIONE DEGLI SCENARI DI SCUOTIMENTO E DI DANNO F. Sabetta, R. Ferlito, M.G. Martini, M. Piersimoni Nell’ambito del progetto NERIES del sesto programma quadro della Comunità Europea (ECFP6), è stato sviluppato un nuovo software per la valutazione di scenari di scuotimento e di danno a seguito di terremoti denominato ELER: Earthquake Loss Estimation Routine (Demirciouglu et al. 2010). In questo lavoro vengono messi a confronto i danni e le vittime causati dal terremoto abruzzese del 06/04/2009 con quelli ottenuti con ELER e col software SIGE attualmente in uso presso il Dipartimento di Protezione Civile (DPC). Il software ELER è stato sviluppato in linguaggio MATLAB ed è dotato di una interfaccia grafica che ne facilita l’uso. In particolare il programma consente di integrare dati esterni provenienti da diverse fonti informative attraverso moduli specifici quali: Txt2Grid per l’inserimento di Shakemaps; Xls2Mat per la creazione di tabelle vulnerabilità-duttilità e costo di ricostruzione per classi di edifici; BDC per creare un inventario di edifici personalizzato che si possa adattare alle esigenze specifiche dell’utente. La Fig. 1 illustra il diagramma di flusso per il calcolo dei parametri di scuotimento del suolo (PGA, PGV, Sa e Sd) nonché dell’intensità macrosismica ricavata da relazioni empiriche con PGA e PGV. Per definire i parametri ipocentrali è possibile inserirli manualmente oppure utilizzare files XML tipo Shakemaps che includono le registrazioni delle stazioni accelerometriche. Si può inoltre utilizzare una sorgente puntuale o una faglia estesa e introdurre diversi tipi di correzioni per tener conto degli effetti di amplificazione di sito. Infine si possono utilizzare diverse relazioni di attenuazione (GMPEs) sia incluse nel programma sia fornite specificamente dall’utente. Il programma provvede automaticamente ad integrare i valori dei parametri di scuotimento registrati (Shakemaps) con quelli ricavati dalle relazioni di attenuazione. Come illustrato in Fig. 2 il programma può lavorare a diversi livelli di dettaglio. Il livello 0 fornisce solo stime approssimative del numero di vittime ed è stato concepito per applicazioni in regioni con scarsi livelli informativi circa la vulnerabilità e l’esposizione. Il livello 1 calcola il numero di edifici danneggiati, di popolazione coinvolta e le perdite economiche ed è basato su relazioni empiriche della vulnerabilità in funzione dell’intensità macrosimica (Lagomarsino e Giovinazzi, 2006) per la valutazione del danno agli edifici e su diversi approcci (Coburn e Spence, 2002; Samardjieva e Badal, 2002) per la stima delle vittime. Ufficio Rischio Sismico e Vulcanico, Dipartimento della Protezione Civile, Roma Fig. 1 - Diagramma di flusso per il calcolo dei parametri di scuotimento del suolo. 394 GNGTS 2011 SESSIONE 2.3 Fig. 2 – Schema a blocchi che illustra la metodologia di analisi multilivello del programma ELER. Fig. 3 - Terremoto abruzzese del 06/04/2009: confronto delle perdite previste da SIGE e ELER con i dai reali rilevati sul campo. Il livello 2 utilizza invece metodologie più approfondite per la valutazione della vulnerabilità basate su modelli analitici calibrati sull’incrocio tra spettri di domanda (accelerazione-spostamento) e spettri di capacità (curva di pushover) secondo il metodo HAZUS-MH (ATC-40, 1996; FEMA, 2003). La Fig. 3 mostra un confronto delle stime di danno ottenute col software SIGE e con i livelli 1 e 2 del software ELER rispetto ai dati reali rilevati sul campo (rilevamenti DPC con scheda AEDES) per il terremoto dell’Aquila di Mw=6.3 del 06/04/2009. Nell’ambito delle notevoli incertezze connaturate a tutti gli scenari di danno, i dati simulati sono abbastanza in linea con quelli reali anche se tutti i metodi risultano piuttosto sottostimati. A questo proposito va precisato che la correlazione tra l’inventario di vulnerabilità degli edifici attualmente utilizzato per l’Italia (7 tipologie basate sul censimento ISTAT 2001) e quello utilizzato dal software ELER (31 tipologie adattate da HAZUS-MH e dal progetto RISK-UE, 2004) va ulteriormente approfondita. 395 GNGTS 2011 SESSIONE 2.3 Bibliografia ATC 40 (1996). Seismic evaluation and retrofit of concrete buildings. Applied Technology Council, Redwood City, California. Coburn, A. and Spence R. (2002). Earthquake Protection (Second Edition), John Wiley and Sons Ltd., Chichester, England. Demircioglu M., Erdik M., Hancilar U., Harmandar E., Kamer Y., Sesetyan K., Tuzun C., Yenidogan C., Zulfikar C. (2010). Earthquake Loss Estimation Routine –V3. Technical Manual. Bogazici University, Department of Earthquake Engineering. FEMA (2003). HAZUS-MH Technical Manual. Federal Emergency Management Agency, Washington, DC, U.S.A Lagomarsino S., and Giovinazzi S., (2006). Macroseismic and mechanical models for the vulnerability and damage assessment of current buildings. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering, Vol.4, pp.415-443. RISK-UE 2004 The European Risk-Ue Project: An Advanced Approach to Earthquake Risk Scenarios.(2001-2004) www.riskue.net Samardjieva, E. and J. Badal, (2002). Estimation of the expected number of casualties caused by strong earthquakes. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 92 (6), pp. 2310-2322 GROUND SHAKING SCENARIOS: THE 8 SEPTEMBER 1905 EARTHQUAKE IN THE GULF OF SANT’EUFEMIA, OFFSHORE WESTERN CALABRIA (SOUTHERN TYRRHENIAN SEA, ITALY) D. Sandron1, M.F. Loreto1, U. Fracassi2, P. Suhadolc3 1 Istituto Nazionale di Oceanografia e di Geofisica Sperimentale - OGS, Trieste, Italy 2 Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia - Roma, Italy 3 Università degli studi di Trieste, Italy The event that occurred on the night of September 8, 1905 (Mw 7.0 – 7.5 according to either instrumental or macroseismic estimates) is probably the strongest earthquake in southern Calabria and likely one of the strongest ever occurred in Italy. This earthquake caused 557 casualties, more than 2000 injured and left about 300,000 homeless. The mainshock was followed by a feeble tsunami and several hundred aftershocks. The very large Mw, the uneven distribution of the macroseismic effects, and their position with respect to the Calabrian arc, all concur to characterize this event as “anomalous”, also in the seismotectonic context of Calabria and of the entire Apennine range, especially when compared with other catastrophic Italian earthquakes. To begin with, its magnitude is perhaps the largest ever-recorded instrumentally in Italy (Ml = 7.9, Dunbar et al., 1992, Ms = 7.47, Margottini et al. 1993; Gruppo di Lavoro CPTI04), larger than that calculated for the catastrophic event of Messina in 1908 (Ms = 7.32, Margottini et al. 1993; CPTI99). Secondly, the damage distribution affected the whole western side of Calabria and beyond, with maximum intensities of X and X-XI MCS. The size of the damage area is comparable only to those caused by the 28 December 1908, Messina earthquake (Mw 7.1), which has occurred some 50 km to the south, and by the 20 February 1743, southern Ionio multiple earthquake, which hit a very large area between Albania and SE Italy. In spite of its very large Mw, the 8 September 1905 seems to have caused no discernible surface faulting. But if for the 1743 and 1908 events the sources were certainly located at sea, in the case of the 1905 earthquake there is no unequivocal evidence of its epicentral location. So was the earthquake of 1905 generated at sea or too deep to give clear evidence on the ground surface? What role had the local geology in the amplification of ground-shaking - and therefore in the assignment to inhabited centres? We will try to answer to these and other questions based on the data stemming from the geophysical, oceanographic and bio-geochemical survey in the Gulf of Sant’Eufemia acquired in the frame of the ISTEGE Project during the summer of 2010 by the R/V OGS-Explora. The aims of this project (Loreto et al., 2011) were: a) to study the active tectonics of the region, and b) to gain insight into tectonic features that could help to identify the potential seismogenic source of the 8 September 1905 earthquake. In this study, in particular, we devised possible shaking scenarios that take into account prospective seismogenic structures associated with the earthquake, both those most accredited in the literature and that emerged from the analysis of the new data. The idea is to strengthen, despite the limitations of the methodology and the uncertainty of the empirical laws used, the choice of a source structure through a comparison of the deterministic scenarios and the macroseismic 396

Scaricare