Saturday, August 15, 8:30pm

THE ROBERT AND JANE MAYER CONCERTS

ANDRIS NELSONS conducting

BARBER

Second Essay for Orchestra, Opus 17

BOITO

“L’altra notte in fondo al mare” from “Mefistofele,” Act III

KRISTINE OPOLAIS, soprano

PUCCINI

Intermezzo from “Manon Lescaut,” Act III

VERDI

Willow Song and “Ave Maria” from “Otello,” Act IV

Ms. OPOLAIS

{Intermission}

STRAUSS

“Ein Heldenleben” (“A Heroic Life”), Tone poem, Opus 40

The Hero—The Hero’s Adversaries—

The Hero’s Companion—The Hero’s Battlefield—

The Hero’s Works of Peace—The Hero’s Escape

From the World and Fulfillment

MALCOLM LOWE, solo violin

Opera activities at Tanglewood are supported by a grant from the Geoffrey C. Hughes Foundation.

NOTES ON THE PROGRAM

Samuel Barber (1910-1981)

Second Essay for Orchestra, Opus 17

First performance: April 16, 1942, Carnegie Hall, New York Philharmonic, Bruno Walter cond. Only

previous BSO performances: December 1998, Leonard Slatkin cond.

The son of a physician, Samuel Barber grew up in a Philadelphia suburb within an environment sympathetic to

his ambition to become a composer. His mother’s sister was the noted contralto Louise Homer. Her husband,

Sidney Homer, a successful composer of art songs, provided encouragement and counsel. Barber entered

Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute at fourteen, where he studied piano, voice, composition, and conducting, and

met Gian Carlo Menotti, the composer who became his intimate companion for most of his life. As a student,

Barber composed some of the works—among them Dover Beach and the Cello Sonata—that are still heard

regularly today.

By the time Barber turned thirty, his pieces had been performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Cleveland

Orchestra, and the New York Philharmonic, and in 1938 Toscanini led the NBC Symphony Orchestra in the

First Essay for Orchestra and the Adagio for Strings. In the years that followed, Barber continued to achieve

auspicious successes, most notably Knoxville: Summer of 1915, premiered by Serge Koussevitzky and the

Boston Symphony Orchestra, a Piano Sonata premiered by Vladimir Horowitz, and Vanessa, an opera with

libretto by Menotti, produced by the Metropolitan Opera in 1958 and awarded the Pulitzer Prize that same

year. At thirty-two, his reputation already well established, he was asked by Bruno Walter for a work in

commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the New York Philharmonic—this was the Second Essay for

Orchestra, premiered at Carnegie Hall on April 16, 1942.

Barber’s early music is characterized by a rather genteel, high-toned lyricism, with straightforward rhythm,

consonant harmony, and clear textures. The Second Essay was written as he entered a new period of

“experimentation,” incorporating elements into his music that other composers were exploring successfully.

Its lyrical primacy, solemn tone, and clarity of harmony, rhythm, and texture are characteristic of his earlier

works, while the pentatonic structure of the main theme, and its emphasis on the intervals of the fourth and

fifth, give it an American flavor—devices new to Barber, but used by a number of other composers during this

period. In addition, its breadth of utterance and reach for grandeur link it to many other American works of the

1940s.

The Second Essay encompasses three main sections: a sort of “prologue,” followed by a scherzo-like

developmental section, which leads to a fervent, hymnlike apotheosis. The opening section presents the

work’s two main themes. The first, the pentatonic theme with its “searching” quality, is introduced by the

flute, picked up by the bass clarinet, and then elaborated by the rest of the orchestra. The music gradually

becomes more animated, leading to the second thematic idea, first in the violas, followed by the oboe, with a

restless, repeated-note accompaniment in the flutes and clarinets. The energy level of the music increases as

the second idea is developed.

The second section follows a loud orchestral chord, as the clarinet and bassoon begin a skittish fugato, based

on the opening theme transformed into a rapid triplet rhythm. The second theme is added to the nervous

polyphonic tapestry, and the two ideas undergo considerable development. Finally, the themes are heard—in

reverse order—closer to their original guise, as the tempo broadens, forming a transition to the third section.

The concluding section is based on a third thematic idea, previously hinted at by the brasses toward the end of

the first section. This hymnlike theme begins softly but richly in the strings and gradually builds in intensity,

as the trumpets and horn add the opening pentatonic theme. The hymn finally culminates in a triumphant

affirmation whose sense of monumentality is remarkable for a work of such modest proportions.

WALTER SIMMONS

A recipient of the ASCAP/Deems Taylor Award for music criticism and a contributor to The New Grove

Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Walter Simmons is a musicologist, author, and critic who specializes in

20th- and 21st-century music.

Arrigo Boito (1842-1918)

“L’altra notte in fondo al mare” from “Mefistofele,” Act III

A musician, poet, novelist, critic, and generally sophisticated man of letters, Arrigo Boito’s legacy as a

librettist is secured through his work with Verdi on Otello and, especially, Falstaff, for which Boito produced

one of the finest librettos in the entire operatic repertoire. His hesitant and self-conscious work as a composer

of his own music was limited in scope and in general far less distinguished, a fact about which he himself had

no delusions, but his output nevertheless contains isolated bright spots. Noteworthy among these are the

Prologue and the Act III prison scene from his only completed opera, Mefistofele, an adaptation of Goethe’s

Faust on his own libretto. An abysmal failure upon its premiere in Milan in 1868, Mefistofele achieved much

more success eight years later in a significantly revised version that had its debut in Bologna, and it continues

to receive occasional revivals, usually as a vehicle to display a star bass in the title role.

“L’altra notte in fondo al mare” opens Act III and is a cri de coeur for the imprisoned Margherita, whom Faust

has seduced with Mefistofele’s help. Margherita, a simple country girl, has inadvertently poisoned her mother

with what Faust told her was an innocent sleeping draught that would allow her to sneak away to their

rendezvous, and is also falsely accused of killing the baby she bore as a result. Confused and abandoned, she

fights against madness and calls to the heavens for mercy in wrenching, virtuosically soaring strains.

JAY GOODWIN

New York-based annotator Jay Goodwin has written for the Metropolitan Opera, Boston Symphony

Orchestra, Juilliard School, and Australian Chamber Orchestra. Currently on the editorial staff at Carnegie

Hall, he was the Tanglewood Music Center’s Publications Fellow in 2009.

MARGHERITA

L’altra notte in fondo al mare

il mio bimbo hanno gittato;

or per farmi delirare

dicon ch’io l’abbia affogato.

L’aura è fredda, il carcer fosco,

e la mesta anima mia

come il passero del bosco

vola, vola via.

Ah, di me pieta!

In letargico sopore

è mia madre addormentata,

è per colmo dell’orrore

dicon ch’io l’abbia attoscata.

L’aura è fredda, ecc.

The other night they cast my baby boy

into the depths of the sea;

now, to drive me mad,

they say I drowned him.

The air is chill, the prison dark,

and my sad soul,

like a bird from the woods,

flies, flies away.

Ah, mercy upon me!

In deepest torpor

my mother lies asleep,

and—more horrible than all—

they say I poisoned her.

The air is chill, etc.

Trans. Dale McAdoo

Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924)

Intermezzo from “Manon Lescaut,” Act III

Puccini’s publisher, Giulio Ricordi, was less than enthusiastic when, in 1889, the composer proposed an opera

based on the Abbé Prévost’s popular but controversial 1731 novel L’histoire du chevalier des Grieux et de

Manon Lescaut and its materialistic, promiscuous, and ultimately doomed heroine. Ricordi’s main concern

was that the story had already been given two operatic treatments, the second of which was Massenet’s very

successful and well-known Manon. But Puccini was undeterred. “Why shouldn’t there be two operas about

Manon? A woman like Manon can have more than one lover,” he wrote. “Massenet feels it as a Frenchman,

with powder and minuets. I shall feel it as an Italian, with a desperate passion.” And, luckily for both him and

Ricordi, he did exactly that. Puccini’s Italianate Manon Lescaut, his third opera, premiered at the Teatro Regio

in Turin on February 1, 1893, and the response was sufficiently rapturous that by the time the 79-year-old

Verdi—the undisputed king of Italian opera for almost half a century—bid farewell with the premiere of his

valedictory Falstaff just over a week later, the succession was already secured.

Though wordless, the orchestral intermezzo that begins Act III is suffused with Puccini’s “desperate passion”

through and through. Positioned at roughly the midpoint of the four-act opera, just as everything has begun to

go horribly wrong for Manon, it marks the beginning of the fickle, feckless, and gold-digging anti-heroine’s

inexorable fall. Having left her young lover from Act I, Des Grieux, when his money ran out, and then become

bored in a bejeweled but frigid affair with his replacement, the wealthy, much older Geronte, Manon has

attempted to abscond with his jewelry and elope once again with Des Grieux. She is caught in the act,

however, and at the conclusion of Act II, Geronte has her arrested for theft. During the intermezzo, Manon is

transported from Paris to a prison in Normandy, where she is held with a group of prostitutes in preparation

for their deportation to Louisiana. Incorporating previously heard motives from the opening two acts—

including, most prominently, the ardent yet star-crossed theme of Manon and Des Grieux’s passion—the

intermezzo serves as a microcosm of the entire sordid tale, offering glimpses of sweetness and building to a

passionate climax, but ultimately turning bitter and spinning out of control. Though the serene, wistful

concluding measures seem to offer a glimmer of hope, any sense of optimism curdles as the curtain rises to

reveal Manon behind bars.

JAY GOODWIN

Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901)

Willow Song and “Ave Maria” from “Otello,” Act IV

In 1879, ten years before Puccini persuaded the reluctant Ricordi to support the Manon Lescaut project,

Ricordi had to do some convincing of his own to coax a new opera out of the aging, increasingly reclusive

Verdi, whose pen had been silent since the Requiem of 1874 and who had not added a new opera to his

catalogue since Aida’s premiere in 1871. Ricordi’s fellow lobbyist was Arrigo Boito, who was to become

Verdi’s final and finest librettist—for which we also have Ricordi, who patched up a rocky relationship

between the two men, to thank. Knowing of Verdi’s lifelong devotion to the works of Shakespeare, a passion

shared by Boito, Ricordi proposed an opera on Othello. Though resistant at first, the prospect of a new opera

on Shakespeare and on Boito’s accomplished first draft of the libretto were impossible for Verdi to resist. The

composition process was lengthy and fragmented and did not begin in earnest until 1884, after Verdi and

Boito solidified their artistic partnership by working together on revisions to Simon Boccanegra and Don

Carlo; but finally, in 1887, audiences in Milan reveled in the triumphant premiere production of Otello, an

innovative new breed of Verdi opera for a new musical climate, one of the genre’s towering masterpieces and

a staggering declaration that the longtime king of Italian music, who had begun to receive criticism for being

conservative and outmoded, was still untouchable.

Desdemona’s Willow Song and “Ave Maria” come from the beginning of Act IV, as Otello’s devoted wife

prepares for bed and awaits the arrival of her husband, who, having been manipulated by the jealous Iago, has

falsely accused her of betraying him with his friend and captain, Cassio. Though Otello has not yet

definitively condemned her, Desdemona seems to know that with her husband comes her death. She sings for

her handmaiden, Emilia, a tune that she can’t seem to get out of her head, a song that she recalls a poor,

heartbroken maidservant of her mother’s singing. Desolate and heartrending, it is at once a remembrance from

her past and a chilling premonition of her future. After she bids Emilia goodnight and farewell, Desdemona

prays an anguished “Ave Maria,” asking for mercy and intercession that she knows will not come.

JAY GOODWIN

VERDI “Otello,” Act IV

Desdemona’s bedroom. A bed, a prie-dieu, a table, a mirror, and some chairs. A lighted lamp hangs before

the image of the Madonna above the prie-dieu. On the right is a door. It is night. Desdemona, with the

assistance of Emilia, is preparing for bed.

[EMILIA

Era più calmo?]*

DESDEMONA

Mi parea.

M’ingiunse di coricarmi

e d’attenderlo.

Emilia, te ne prego,

distendi sul mio letto

la mia candida veste nuziale.

[EMILIA

Was he calmer?]

DESDEMONA

He seemed so to me.

He commanded me to go to bed

and there await him.

Emilia, I pray you,

lay upon my bed

my white wedding nightgown.

(Emilia does so.)

Senti.

Listen.

Se pria di te morir dovessi,

If I should die before you,

mi seppellisci con un di quei veli.

lay me to rest in one of those veils.

[EMILIA

[EMILIA

Scacciate quest’idee.]

Put such thoughts from you.]

DESDEMONA

DESDEMONA

Son mesta tanto, tanto.

I am so sad, so sad.

(seating herself mechanically before the mirror)

Mia madre aveva una povera ancella,

My mother had a poor maidservant,

innamorata e bella;

she was in love and pretty;

era il suo nome Barbara;

her name was Barbara;

amava un uom che poi l’abbandonò.

she loved a man who then abandoned her.

Cantava una canzone,

She used to sing a song,

la canzon del Salice.

“The Song of the Willow.”

(to Emilia)

Mi disciogli le chiome.

Unbind my hair.

Io questa sera ho la memoria piena

This evening my memory is haunted

di quella cantilena.

by that old refrain.

“Piangea cantando nell’erma landa,

“She wept as she sang on the lonely heath,

piangea la mesta,

the poor girl wept,

O Salce! Salce! Salce!

O Willow, Willow, Willow!

Sedea chinando sul sen la testa,

She sat with her head upon her breast,

Salce! Salce! Salce!

Willow, Willow, Willow!

Cantiamo! cantiamo!

Come sing! Come sing!

Il salce funebre sarà la mia ghirlanda.” The green willow shall be my garland.”

(to Emilia)

Affrettati; fra poco giunge Otello.

Make haste; Othello will soon be here.

“Scorreano i rivi fra le zolle in fior,

“The fresh streams ran between the flowery

gemea quel core affranto,

banks, she moaned in her grief,

e dalle ciglia le sgorgava il cor

in bitter tears flowing from her eyes,

l’amara onda del pianto.

her poor heart sought relief.

Salce! Salce! Salce!

Willow! Willow! Willow!

Cantiamo! cantiamo!

Come sing! Come sing!

Il salce funebre sarà la mia ghirlanda.

The green willow shall be my garland.

Scendean l’augelli a vol dai rami cupi

Down from dark branches flew the birds

verso quel dolce canto.

toward the singing sweet.

E gli occhi suoi piangean tanto, tanto,

So copious were the tears she wept

da impietosir le rupi.”

that even stones shared her sorrow.”

(to Emilia, taking a ring from her finger)

Riponi quest’anello.

Lay this ring by.

(rising)

Poor Barbara!

The story used to end

with this simple phrase:

“He was born for glory,

I to love...”

(to Emilia)

Ascolta. Odo un lamento.

Hark! I heard a moan.

(Emilia takes a step or two.)

Taci... Chi batte quella porta?

Hush... Who knocks upon that door?

[EMILIA

[EMILIA

È il vento.]

’Tis the wind.]

DESDEMONA

DESDEMONA

“Io per amarlo e per morir.

“I to love him and to die.

Cantiamo! cantiamo!

Come sing! Come sing!

Salce! Salce! Salce!”

Willow! Willow! Willow!”

Emilia, addio.

Emilia, farewell.

Come m’ardon le ciglia!

How mine eyes do itch!

È presagio di pianto.

That bodes weeping.

Buona notte.

Good night.

(Emilia turns to leave.)

Ah! Emilia, Emilia, addio!

Ah! Emilia, Emilia, farewell!

Emilia, addio!

Emilia, farewell!

(Emilia returns and Desdemona embraces her.

Emilia leaves. Desdemona kneels at the prie-dieu.)

Ave Maria, piena di grazia,

Hail Mary, full of grace,

eletta fra le spose e le vergini sei tu,

blessed amongst wives and maids art thou,

sia benedetto il frutto, o benedetta,

and blessed is the fruit, o blessed one,

di tue materne viscere, Gesù.

of thy maternal womb, Jesu.

Prega per chi, adorando a te, si prostra,

Pray for those who kneeling adore thee,

prega nel peccator, per l’innocente,

pray for the sinner, for the innocent

e pel debole oppresso e pel possente,

and for the weak oppressed; and to the

powerful man,

misero anch’esso, tua pietà dimostra.

who also grieves, thy sweet compassion show.

Prega per chi sotto l’oltraggio piega

Pray for him who bows beneath injustice

la fronte,

e sotto la malvagia sorte;

and ’neath the blows of cruel destiny;

per noi, per noi tu prega,

for us, pray thou for us,

prega sempre,

pray for us always,

e nell’ora della morte nostra,

and at the hour of our death

prega per noi, prega per noi,

pray for us, pray for us,

prega!

pray!

(She remains kneeling and, with her head bowed on the prie-dieu,

repeats the prayer silently, so that only the first words and the last are audible.)

Ave Maria...

Hail Mary...

... nell’ora della morte.

... at the hour of our death.

Ave!... Amen!

Hail!... Amen!

Povera Barbara!

Solea la storia con questo

semplice suono finir:

“Egli era nato per la sua gloria,

io per amar...”

Trans. © Decca Music Group Ltd.

Richard Strauss (1864-1919)

“Ein Heldenleben” (“A Heroic Life”), Tone poem, Opus 40

First performance: March 3, 1899, at a Frankfurt Museum concert, Strauss cond. First BSO performances:

December 1901, Wilhelm Gericke cond. First Tanglewood performance: July 29, 1962, Erich Leinsdorf cond.

Most recent Tanglewood performance: July 11, 2010, Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos cond.

Seventy-eight years separate Strauss’s first composition and his last. For almost forty years, he devoted most

of his energies to opera, though he was a man of forty-one at the premiere of Salome in December 1905. He

had completed an opera called Guntram as early as 1893, but it disappeared from the stage almost

immediately. The Guntram experience cost him lots of headaches, both in Weimar, where he was conductor

from 1889 to 1894, and later in Munich, his next way-station. His happiest association was his engagement

during the rehearsal period and his marriage four months later to his pupil Pauline de Ahna, who took the

principal female role. Pauline plays an important part in Ein Heldenleben, as well as in such works as the

Symphonia domestica and the opera Intermezzo. The sound and the memory of her luminous soprano inform

countless pages in his opera scores and songs; and in the setting of Eichendorff’s Im Abendrot (one of the Four

Last Songs), Strauss built a wondrously moving monument to their enduring devotion.

After Guntram, at any rate, Strauss returned to a path he had already explored for a half-dozen years, that of

the orchestral tone poem. Reared in a conservative, classical tradition, having just arrived at Brahms by way of

Mendelssohn, Chopin, and Schumann, the twenty-one-year-old Strauss had fallen under the thrall of a much

older composer and violinist, Alexander Ritter, who made it his task to convert his young friend to the “music

of the future” of Liszt and Wagner. Strauss’s first and still somewhat tentative compositional response was the

pictorial symphonic fantasy Aus Italien (“From Italy”), which, at least to some degree, was still tied to the old

tradition. But the next work, Don Juan, completed September 1888—a work of astonishing verve, assurance,

and originality—represented total commitment to the “future.” Even allowing for the interruption to complete

Guntram, the series of tone poems was continued at high speed and with the most vigorous invention: Death

and Transfiguration in 1889, the revised Macbeth in 1891, Till Eulenspiegel in 1895, Thus Spoke Zarathustra

in 1896, Don Quixote in 1897, and Ein Heldenleben in 1898. Two postscripts followed at some distance—the

Symphonia domestica in 1904 and the Alpine Symphony in 1914—but the period of intense concentration on

the genre comes to an end with Heldenleben.

“Ein Heldenleben” is usually translated as “A Hero’s Life”; argument, however, could be made that “A Heroic

Life” comes even closer. But who is the hero? Two details point to Strauss himself. Though generally irritated

by requests for “programs” and insistent that music’s business was to say only those things that music could

uniquely say, Strauss authorized his old school friend Friedrich Rösch and the critic Wilhelm Klatte to supply,

for the premiere on March 3, 1899, a detailed scenario in six sections. One of these is called “The Hero’s

Companion” and it is, by the composer’s admission to Romain Rolland and others, a portrait of Pauline

Strauss. Another is called “The Hero’s Works of Peace” and is woven from quotations of earlier Strauss

scores.

The first large section of the work, swaggering, sweet, impassioned, grandiloquent, sumptuously scored,

depicts The Hero in his changing aspects and moods. Next comes the scene of The Hero’s Adversaries, the

grudgers and the fault-finders, including drastically different music—sharp, prickly, disjunct, dissonant.

Strauss was convinced that some of the Berlin critics recognized themselves as the target of this portrait and

the composer as The Hero. The Hero’s theme, on its next appearance, is much darkened.

One violin detaches itself from the others to unfold the vivid portrait of Pauline. Gay, flippant, tender, a little

sentimental, exuberantly playful, gracious, emotional, angry, nagging, loving—these are some of the

directions to the violinist in this scene of The Hero’s Companion. The single violin is again absorbed into the

orchestral mass and we hear love music, as lush as only Strauss could make it. Briefly the adversaries disturb

the idyll, but their cackling is heard as though from a distance. But the hero must go into battle to vanquish

them. Trumpets summon him, introducing that immense canvas, The Hero’s Battlefield. The hero returns in

triumph, or, in musical terms, there is a recapitulation as clear and as formal as the most ardent classicist could

wish.

The music becomes more quiet and we have arrived at one of the score’s most remarkable sections, The

Hero’s Works of Peace. Here Strauss weaves a texture both dense and delicate as he combines music from

Don Juan, Also sprach Zarathustra, Death and Transfiguration, Don Quixote, Macbeth, and his song Traum

durch die Dämmerung (“Dreaming at Twilight”). This episode is one of Strauss’s orchestral miracles, richly

blended, yet a constantly astonishing, shifting kaleidoscopic play of luminescent textures and colors.

Even now, the adversaries are not silenced. The hero rages, but his passion gives way to renunciation (this is

indeed very unlike the real Richard Strauss). The final section is called The Hero’s Escape from the World

and Fulfillment. The hero retires—to Switzerland, on the evidence of the English horn—and, after final

recollections of his battling and loving self, the music subsides in profound serenity. This, in the original

version, was undisturbed through the pianissimo close with violins, timpani, and a single horn. But Strauss

reconsidered, and in the few days between Christmas 1898 and the New Year he composed the present ending

with its rich mystery and fascinating ambiguity, an ending of marvelously individual sonority, and one that at

least touches fortissimo.

MICHAEL STEINBERG

Michael Steinberg was program annotator of the Boston Symphony Orchestra from 1976 to 1979, and after

that of the San Francisco Symphony and New York Philharmonic. Oxford University Press has published

three compilations of his program notes, devoted to symphonies, concertos, and the great works for chorus and

orchestra.

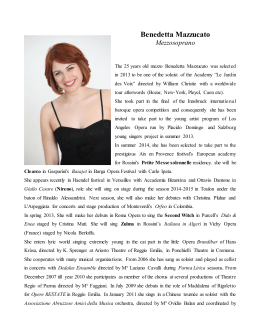

Guest Artist

Kristine Opolais

Kristine Opolais is one of the most sought-after sopranos on the international scene today, appearing regularly

at the Metropolitan Opera, Wiener Staatsoper, Deutsche Staatsoper Berlin, Bayerische Staatsoper, Teatro alla

Scala, and the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, working with such conductors as Daniel Barenboim,

Antonio Pappano, Daniel Harding, Louis Langrée, Andris Nelsons, Gianandrea Noseda, Marco Armiliato,

Marc Minkowski, Fabio Luisi, Kirill Petrenko, Alain Altinoglu, and Kazushi Ono. In the 2015-16 season Ms.

Opolais returns to the Metropolitan Opera for a much-anticipated new production of Puccini’s Manon Lescaut,

singing the title role alongside Jonas Kaufmann. Manon Lescaut has become a signature role for the soprano,

following her 2014 appearances in two new productions of the opera, at the Royal Opera House and

Bayerische Staatsoper. In spring 2016 she also appears at the Metropolitan Opera as Cio-Cio San in Madama

Butterfly; both this opera and Manon Lescaut will be broadcast to cinemas as part of the Met’s “Live in HD”

series. Ms. Opolais has maintained a strong relationship with the Metropolitan Opera since her 2013 debut

there as Magda in La Rondine. In April 2014 she made Met history, when, within eighteen hours, she made

house debuts in two roles, giving an acclaimed, scheduled performance as Cio-Cio San in Madama Butterfly,

then stepping in as Mimì for a matinee performance of La bohème the very next day—a performance

broadcast to cinemas around the world. Continuing her association with the Bayerische Staatsoper, she makes

two role debuts there in 2015-16: as Margherita and Helen of Troy in Boito’s Mefistofele and as Rachel in

Halévy’s La Juive. Since her 2010 Bayerische Staatsoper debut, when she stepped in to sing the title role in

Dvorák’s Rusalka, she has appeared there as Cio-Cio San, Amelia in Simon Boccanegra, Vitellia in La

clemenza di Tito, and Tatiana in Eugene Onegin. Her collaboration with the Royal Opera House, Covent

Garden, has featured the Puccini roles of Cio-Cio San, Floria Tosca, and Manon Lescaut. She has also

appeared at Opernhaus Zürich in the title role of Jen˚ufa and recently made her house debut at Opéra National

de Paris Bastille. Recent concert performances have included appearances at the Salzburg Festival,

Tanglewood, the BBC Proms, and with the Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, WDR

Sinfonieorchester Köln, Tonhalle Orchester Zürich, Stockholm Philharmonic, and Filarmonica della Scala.

Highlights of 2015-16 include her debut with the Concertgebouw Orchestra under Semyon Bychkov and

concerts with the Boston Symphony Orchestra and Andris Nelsons on their 2016 European tour, to include her

Musikverein debut. Recent DVD recordings have included Deutsche Staatsoper’s production of Prokofiev’s

The Gambler, in which she sang Polina under the baton of Daniel Barenboim; Rusalka from the Bayerische

Staatsoper production, Don Giovanni from the Aix-en-Provence Festival, and Eugene Onegin from Valencia’s

Palau de les Arts Reina Sofia. A recent Orfeo International CD recording with WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln

of Puccini’s Suor Angelica was nominated for a BBC Music Magazine Award, and her latest release is Simon

Boccanegra with the Vienna Symphony on Decca. Kristine Opolais made her Boston Symphony Orchestra

debut in July 2013 at Tanglewood, in a performance of Verdi’s Requiem. She made her first Symphony Hall

appearance with the orchestra in September 2014, as a soloist in Andris Nelsons’ inaugural concert as the

BSO’s music director, a concert subsequently telecast in the PBS series “Great Performances.”

Scarica

![Cimarosa – Il matrimonio segreto (Barenboim) [1976]](http://s2.diazilla.com/store/data/000944491_1-35b7d873231db3aa6e9645f1a02454aa-260x520.png)