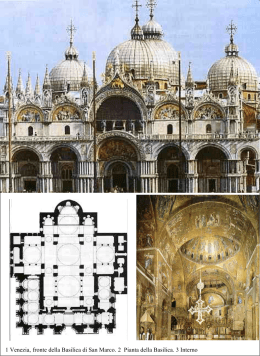

Sassifraga 79 Laura Lilli FORMICHE STRAORDINARIE EXTRAORDINARY ANTS Disegni di / Drawings by Elisa Montessori Traduzione di / Translated by Jehanne Marchesi Empirìa © Edizioni Empirìa 2010 Via Baccina, 79 - 00184 Roma Tel. 06.69940850 / fax 06.45426832 P. IVA 05801771006 ISBN 978-88-96218-04-4 Internet: www.empiria.com E-mail: [email protected] 6 Chilometro Un giorno una poeta scontenta della scarsa attenzione che riceveva dal mondo (almeno, così le sembrava), decise di scrivere una poesia memorabile, che non potesse assolutamente passare inosservata. Sì – disse a se stessa – la scriverò tutta in un verso, e questo verso sarà lungo un chilometro. Non ci sarà nessuno che riuscirà a non vederla e a non leggerne almeno un pezzo. Fantasticando e mormorando, contenta, uscì di casa. La prima immagine le sgorgò in testa subito, quasi senza pensare, e le diede una certa euforia. Era evidentemente in un momento di felice concentrazione perché anche lavorare sull’immagine, farla lievitare, trarne le prime conseguenze e dar loro un seguito non fu affatto laborioso, anzi ogni nuova parola le dava nuova energia. Camminava e componeva, poco attenta a quel che le succedeva intorno. Uscì dal cancello automaticamente, girò a destra, e prese una strada che conosceva. Attraversò incroci con e senza semaforo, passò due ponti e due archi, gettò uno sguardo automatico al fiume che conosceva fin da bambina. L’aria era fine, la temperatura era giusta, il cielo blu con qualche virgola di nuvoletta chiara che sembrava pagata dal Comune. Quanto ai ruggiti del traffico, non li sentiva, immersa com’era nel più profondo di se stessa e della sua poesia, tutta intenta a non usare aggettivi e parole in più. Si riteneva un’abile tagliatrice di quel che scriveva, e ogni tanto l’assaliva la preoccupazione che a un chilometro non ci sarebbe mai arrivata, tanta era l’attenzione che poneva nello scartare le parole troppo facili, imprecise o superflue. 7 Invece, ci arrivò. Camminò un paio di chilometri e, attraversando un viale alberato, ebbe la certezza di avere costruito un chilometro di poesia. Le sillabe, i punti e le virgole la seguivano saltellando, ruzzando e rotolandosi sul marciapiede come cuccioli, talvolta aggregandosi e disaggregandosi fra loro per gioco. Segno che è un bel verso, – pensò la donna – altrimenti non sarebbe così felice. Cammina cammina, giunse il momento in cui si sentì stanca. Aveva compiuto la sua opera: ora meritava un po’ di riposo. Faceva caldo. Non lontano, vide una Basilica, e ci si rifugiò. Le sillabe, i punti e le virgole, dietro a lei. Composti. Si recitava il Rosario. La nenia dell’orazione la cullò fino a farla addormentare. Si svegliò ritemprata, e subito, memore dell’opera compiuta, fu di nuovo felice. Era ora di tornare a casa. Ma il verso, che si era compattato in un chilometro esatto, non voleva saperne di uscire dalla Basilica. Era di un materiale durissimo e sbatacchiava di qua e di là, scoperchiando confessionali, decapitando statue, sgretolando affreschi, spaccando cornici dorate e preziosi calici di cristallo e d’oro. Di questi, alcuni si frantumarono e piovvero a terra in frammenti, tintinnando come in un lamento. Altri presero a rotolare irregolarmente, risuonando, sui mosaici della navata altissima, sotto gli occhi allibiti e terrorizzati dei preti accorsi e dei fedeli che saltellavano fra i calici e, impauriti a loro volta, cercavano di mettersi a debita distanza, recitando giaculatorie. Qualcuno parlò di chiamare i pompieri, qualcun altro la polizia. Spaventata, la poeta cercò di far uscire almeno una parte del verso dalla porta che, per disdetta, era a tamburo. Un pezzo riuscì a cacciarlo fuori, in un fracasso d’inferno, rompendo i vetri del tamburo. Ma la poeta, che era ancora nella Basilica, temeva anche che in strada quell’affare lungo e pesante avrebbe ferito, magari ucciso qualcuno. Tuttavia le sembrava già di sentire le sirene che si avvicinavano: il panico fece tacere in lei ogni scrupolo e senso di colpa, e prese una decisione drastica. 8 Provvisoriamente, – si disse – lo frammenterò, come gli architetti fanno coi loro metri quando li ripiegano. In questo modo ce la fece ad uscire affannosamente con tutto il suo verso, e ad allontanarsi un po’ facendosi largo tra la folla che si era formata, proprio mentre il camion dei pompieri, a sirene accese, si fermava davanti alla Basilica. Si vergognava di sé e si sentiva vile, ma cercò di ripetersi che la poesia ha dei diritti che tutti gli altri non hanno. Non ci credeva nemmeno lei, e forse proprio per questo ora il verso, ridotto a una sorta di fascina, le pesava tremendamente nel camminare. Adesso la città, da amica che era, le era divenuta ostile. Il traffico era rumoroso e confuso. Per giunta la fatica la faceva procedere così lentamente, trascinando i piedi sull’asfalto, che quando attraversava, anche se cominciava col verde, finiva sempre per trovarsi col rosso ancora a mezza via, suscitando cori inviperiti e impazienti di clacson che le ferivano le orecchie. Qualcuno, sporgendosi dai finestrini, la insultava. Molti motorini strusciarono sul verso spezzettato e le ferirono le nocche delle dita, zigzgando, accelerando, e lasciandosi dietro una scia di imprecazioni. I ponti erano interminabili, le salite ripide. Si stava facendo tardi. Il cielo si era rannuvolato. Stava per piovere: e se la pioggia avesse scolorito, o addirittura cancellato il verso? Dubitò di farcela a percorrere il chilometro che ancora la separava dalla sua casa. Ansimante e sudata, si fermò un momento appoggiando il pesantissimo verso sulla spalletta del lungofiume. Che fare? Guardava la corrente, fangosa e rabbiosa sotto le nuvole basse. Ebbe la tentazione di buttarci dentro il suo fardello pesantissimo, e che andasse al diavolo. Si riprese. No. Il suo bel verso, la sua creatura non la avrebbe buttata in acqua. Aveva già devastato una Basilica, e ora ci mancava solo un infanticidio. Però qualcosa bisognava fare, e in fretta. Ecco, – pensò – solo fino all’arrivo a casa, potrei frammen9 tarlo ancora di più. Poi lo ricostruirò. Tanto, non è che non me lo ricordi: l’ho scritto io… Sfiorò il verso, e… tac. Si divise in una serie di “a capo” melodiosi che sembrava danzassero a un ritmo sconosciuto ma incantevole. E dalla durezza di quella materia così refrattaria a rompersi si trasformò in uno sciame di farfalle, una nuvoletta viva, fremente e docile, fatta di sillabe messe in conseguenza. Non dovette più portarlo. Il verso le saltellava intorno alla testa formando un alone luminescente mentre lei camminava, di nuovo leggera. Le aleggiava intorno, un po’ più avanti, un po’ più indietro. La seguì oltre il cancello, nell’ascensore, fuori dell’ascensore continuando a svolazzare e a posarsi fra i suoi capelli mentre frugava nello zaino alla ricerca delle chiavi di casa. E, una volta che lei fu entrata, andò a depositarsi sul suo tavolo. Non si ricompattò nella lunghezza originaria. Era chiaro che lì, palpitante e fremente sulla sua scrivania, aspettava che lei dicesse qualcosa. E lei lo disse. Disse: Sai che c’è? Io al chilometro ci rinuncio. Magari non nel titolo: ‘Chilometro’ – mormorò fra sé (ma il verso, tutt’orecchie, sentiva tutto). Sì,‘Chilometro’. Sì, sì, mi piace. Può andare. Ecco, così ho trovato anche il titolo, e per il resto la poesia resterà com’è ora. È bella e solida, e ha un ritmo che è proprio mio. Se non tutti la apprezzeranno, pazienza. Io mi sento leggera e contenta come all’andata, e sono soddisfatta del mio lavoro. Divenuto una poesia, il verso lungo un chilometro e intitolato Chilometro fu stampato in un libretto piccolo piccolo, dalle pagine larghe non più di venti centimetri. Piacque a molti, forse anche perché aveva un titolo tanto più lungo del suo formato, e ricevette vari premi. E la poeta e la sua poesia furono contente. 10 The story of a mile-long line of verse One day a poetess who was unhappy about how little attention the world paid her (at least so she thought) decided to write a memorable poem which simply could not pass unobserved. Yes – she said to herself – I’ll write it all in one line – a mile long line. No-one will be able to avoid seeing it and reading at least a part of it. Thinking about it and murmuring happily to herself, she went out. Almost immediately the first image sprang from her head and produced a certain euphoria. She was obviously in a moment of happy concentration since working on the image, making it ‘rise’, drawing the first consequences and following them up was not laborious, in fact each word gave her new energy. She walked and composed, oblivious of what was going on around her, automatically walking out of the gate, turning right, and taking a street she knew. She passed crossroads with or without traffic-lights, went over two bridges and under two arches, automatically glanced at the river which she had known since she was a child. The air was transparent, the temperature right, the sky blue with a few wisps of light clouds which looked as if they had been paid for by the Municipality. As for the roar of the traffic, she didn’t hear it, immersed as she was in the very depths of herself and her poetry and intent on not using extra adjectives and words. She considered herself an able ‘cutter’ of her own texts and every now and then was assailed by the worry that she would never reach a mile because she was so busy discarding words that were too easy, imprecise or superfluous. 12 Instead she did reach it. She walked for a couple of miles, crossing the tree-lined avenue, and then, at one point, was certain that she had constructed a mile of poetry. The syllables, the full stops and commas skipped along behind her, romping and rolling on the pavement like puppies, at times playfully joining together and at times parting. “It’s a sign that it’s a fine line”, the woman thought, “otherwise it wouldn’t be so happy”. She walked and walked until she was tired. She had accomplished her work: now she deserved a little rest. It was hot. She saw that she was near a Basilica and took refuge in it. The syllables, full stops and commas followed right behind. Sedately. People were reciting the Rosary. The singsong of the prayer lulled her to asleep. She woke up refreshed and, remembering the work she had accomplished, was happy again. It was time to go home. But the line of verse, which had contracted into exactly one mile, refused to leave the Basilica. It was made of a very hard substance and it banged about, uncovering confessionals, decapitating statues, scratching gilt frames and frescoes and breaking precious gold and crystal chalices. Some fell to the ground, tinkling lamentably, others rolled around, echoing on the moisaics of the high nave, under the horrified eyes of the priests who had rushed to the scene and the faithful who were afraid and remained at a safe distance. Somebody spoke of calling the firemen, others the police. Alarmed, she tried to get at least part of the line of verse out of the door which unfortunately was a revolving-door. Though she managed to get one piece out, in an infernal noise, breaking the pane of glass. The poetess, who was still inside the Basilica, was afraid that even in the street such a long and heavy thing might hurt or even kill someone. However she thought she already heard the sirens approaching: panic silenced any scruple and sense of guilt she might have and she took a drastic decision. Provisionally – she said to herself – I’ll split it up, like architects do with their yardsticks when they fold them. 13 In this way she managed to get out breathlessly, with her whole line of verse, and move a little way off while the fire engine pushed through the crowd which had formed and stopped in front of the Basilica. She felt ashamed and cowardly but tried to convince herself that poetry has rights which don’t belong to everyone. In fact she didn’t believe it herself and this may have been why the line of verse, reduced to what looked like a bunch of twigs, weighed tremendously as she walked. The city, from being friendly, now became hostile. The traffic was loud and confused. Besides, exhaustion slowed her down – she almost dragged her feet along the asphalt – and when she crossed a street, even if the light was green when she set out it always turned red while she was still half way, causing furious and impatient honking choruses which hurt her ears. Some people even leant out of their windows to insult her. And scooters brushed against the fragmented line of poetry, grazing her knuckles, zigzagging, accelerating, and leaving a wake of invective behind them. The bridges were interminable, the slopes steep. It was growing late. The sky had clouded over. It was about to rain, and what if the rain discolored or even effaced the line of poetry? She doubted that she would be able to cover the mile which still separated her from home. Panting and hot, she stopped for a moment and leant the heavy line of verse against the parapet of the embankment. What should she do? She observed the angry and muddy current under the low clouds. She was tempted to throw her heavy load into it – and it could go to the devil. She rallied. No. Her lovely line of verse, her creature – she wouldn’t throw it in. She had already devastated a Basilica, and now only an infanticide was missing. But she had to do something, and quickly. Why yes – she thought – I could split it up even more, temporarily. And then I’ll put it together again. Anyhow, I’ll remember it: it’s I who wrote it… 14 She lightly touched the line of poetry and… oops… it split into a series of melodious new lines which seemed to dance to an unknown but enchanting rhythm. And a swarm of butterflies rose from that hard, refractory substance – a living cloud, quivering and docile, composed of consequential syllables. She didn’t have to carry it any more. The line of poetry fluttered around her head like a luminescent halo as she walked, feeling light again. It flew around, in front of her or behind her. It followed her through the gate, into the lift, out of the lift – still fluttering as she searched her rook-sack for her keys – and, once inside, went to rest on her table. It didn’t recompose into its original length. Palpitating and quivering on her desk, it clearly was waiting for her to say something. And she did. She said: Do you know what? I give up on the mile, though not on the title: “A mile-long line of verse”. She repeated it to herself (but the line of verse, which was all ears, heard everything), – “A mile-long line of verse”. – Yes, I like that, it’ll do. And so I’ve also found the title, though otherwise I’ll leave the poem as it is. It’s lovely and solid, and the rhythm is truly mine. It doesn’t matter if it doesn’t please everyone. I feel as light and happy as I was when I went out, and satisfied with my work. Having become a poem, the mile-long line of verse, called Mile, was printed in a tiny little book whose pages were only a few inches wide. Many people liked it, possibly also because its title was so much longer than its format, and it received several prizes. And the poetess and her poem were pleased. 15 Piscine E. arrivò sul bordo della piscina con il giornale appena comprato. Voleva dargli una scorsa, ma era pronta a cederlo a qualcuno dei suoi ospiti che prendeva il sole. Scivolò un poco sul bordo bagnato, e il giornale cadde in acqua. E fu lesta a raccoglierlo. Non si era bagnato troppo. Lo mise ad asciugarsi al sole. Poi squillò il telefono del salotto, lei corse dentro e il giornale restò lì, fra gli ospiti sdraiati e leggermente inebetiti dall’aria aperta. Tirava una leggera brezza e le pagine del giornale, sfogliandosi mano a mano al sole, cominciarono a sbiadire. Sbiadivano le pagine, sbiadivano le notizie. Una guerra cruenta in prima pagina, un testacoda con morto nella Formula Uno, contestazione alla prima di un film, calo improvviso in Borsa delle azioni di una famosa società agroalimentare. Gli ospiti sbadigliarono, si stirarono, nuotarono un po’, pigramente, poi si ritirarono nelle proprie stanze. Il giornale rimase lì, ormai bianco. Dall’erba uscì una fila di formiche e lo riscrisse tutto in cinese. 19 Swimming pools Julia arrived at the edge of the swimming pool with the newspaper she had just bought. She wanted to have a look at it, but was ready to give it up to one of her sunbathing guests. She slipped slightly on the wet edge and the newspaper fell into the water. She was quick to fish it out. It wasn’t too wet. She put it in the sun to dry. Then the living room phone rang and she ran in, leaving the newspaper where it was among her prone guests, who were a little groggy because of the open air. There was a slight breeze and the newspaper pages blew over in the sun, one by one, and began to fade. The pages faded, the news faded. A bloody war on the front page, a bad collision with a victim during the Formula One races, a protest at a film première, a sudden drop on the Stock Exchange of a famous agriculture and food company’s shares. The guests yawned, stretched, lazily swam a little and then went to their rooms. The paper stayed where it was. By now it was white. A line of ants came out of the grass and re-wrote it all in Chinese. 21 Le due eternità Che ora è? – chiese sbadigliando e stiracchiandosi la Basilica Julia nel Foro Romano. Un occhio era semiaperto e l’altro ancora chiuso nel sonno. Bah, non saprei – rispose il Tempio di Castore e Polluce mentre stendeva le sue tre colonne in un energico e sano stretching da dopo-risveglio. Sembrerebbe l’ora sesta, ma non vedo clessidre in giro… Asini! È un pezzo che le clessidre sono scomparse! – esclamò una voce forte, che veniva da dietro il Colosseo. E anche le meridiane! – aggiunse un’altra voce, altrettanto robusta, proveniente dalla direzione opposta. L’ora oggi si guarda sugli orologi – aggiunse la prima voce. Orologgi? E che sarebbono? – chiese la Via Sacra, che parlava un linguaggio popolare, percorsa com’era stata da tante migliaia di sandali, alcuni, è vero, nobili e senatoriali, ma soprattutto plebei. Una volta il poeta Orazio c’era andato a farsi due passi in pace, e un seccatore lo aveva importunato. Questo episodio che li nobilitava, i lastroni della via Sacra non se lo erano mai dimenticato. E in memoria di quello, ogni tanto si sforzavano di parlare “pulito”, ma l’esperimento riusciva di rado. Gli orologi sono le macchine moderne per misurare l’ora – spiegò la prima delle voci sconosciute. – E guardate quanti ce ne sono in giro per questa nostra bella Roma… …già – le rispose la seconda voce. – Peccato che non sappiano mai che ora è veramente. E la prima voce, di rimando, in un dialogo che passava direttamente sopra la testa del Foro Romano, come se questo non esistesse: Beh, dopo tutto noi apparteniamo all’eternità. Il tem25 po francamente non ci interessa poi tanto. Peccato, semmai, per gli esseri umani, i pellegrini. Eternità?? Pellegrini? – chiesero beffardi i Rostra. Dell’antica tribuna del Foro restava poco, e i tanti gloriosi speroni strappati alle navi puniche ad Anzio nel 338 a. C. ormai erano scomparsi. La base dell’antica tribuna rimaneva però, solida e forte, e conservava il carattere aggressivo dovuto in parte all’aver sempre fatto da pulpito, un po’ all’indignazione di quando la testa del miglior oratore dell’Urbe, Cicerone, era stata esposta proprio sui “rostra” sporcandoli del suo sangue. Siamo noi che siamo parte di Roma eterna – riprese la basilica Julia, affrettandosi a parlare perché sperava di chiudere la bocca a quel vicino chiacchierone, che non aveva mai digerito per antico che fosse. Si sentiva così fastidiosamente legato alla gens Julia perché il comitium glielo aveva messo a tanto poca distanza quando Cesare aveva risistemato il Foro. Come se non bastasse, lui si sentiva il centro del Foro, perché proprio alle sue spalle stava la piattaforma circolare che sosteneva l’“umbilicus Urbis”, quello sì centro simbolico di Roma e dunque del mondo. Disse dunque in fretta: Eterni siamo noi del Foro in primo luogo. E poi, si capisce, il Palatino, la Domus Aurea, la Piramide, il Colosseo, gli archi di Settimio Severo, Tito e di Costantino, i Mercati Traianei… insomma, noi romani. Non so se mi sono spiegata. La via Sacra perse la pazienza: Ma se po’ sape’ chi ve credete da esse, voi altri due? E che cazzo c’entrate con l’eternità? L’eternità è nostra. Nostra de Roma e basta. Roma? Certo. La mia città. L’ho fondata io e le ho dato il mio nome. Da lontano giunse la voce assonnata del Tempio di Romolo. Che continuò: Sì, disegnammo un quadrato con mio fratello Remo, però lui poi morì in un misterioso incidente. Ma non rivanghiamo il passato. Pensiamo al nostro presente, e a un futuro glorioso. 26 Noi conquisteremo il mondo! Guerra! Guerra, nipoti di Marte! Andiamo subito a rapire le Sabine. Se i Sabini si ribelleranno, li sottometteremo. I vitelli dei romani sono belli! Calma. Stai calmo, vecchio Re. Torna al tuo sonno – gli rispose la basilica Julia, con una dolcezza che sbalordì la Via Sacra. Chi crediamo di essere? – chiedeva intanto la prima voce sconosciuta. Chi siamo, vorrete dire. Io personalmente sono la basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano, cattedrale di Roma… E io la Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, edificata proprio lì dove ai vostri tempi nevicò il cinque agosto. E siamo due delle sette basiliche maggiori di Roma… Modestamente, fra le più belle… E daje a insistere co’ Roma! – intervenne la Via Sacra. – E sareste pure belle! Ma come ce siete arrivate, fino a qui? E chi ve conosce, vorrei sapé? Silenzio, Via Sacra. Oppure parla con un linguaggio degno di un membro costitutivo del Foro Romano – intervenne la Basilica Julia, con tutta la padronale autorevolezza della propria nobiltà. Ormai s’era fatta piccola, risucchiata in se stessa come certe vecchie nobildonne: e come loro, più gli anni la divoravano, riseccandola e restringendola come una prugna, più dai resti dei suoi marmi trasparivano le venature blu dei suoi “quattro quarti” di sangue nobile. Si rivolse alle due voci invisibili con affettazione e sussiego: Dunque sareste sette. E posso pregarvi, gentili signore, di dirci chi e quando vi ha conferito, a nostra insaputa, il diritto di definirvi ‘basiliche’? Perché, a quanto mi risulta (e oserei dire che a me, così come alla mia senatoriale amica Curia, qui, proprio di fronte a me, risulta tutto quello che deve risultare), Basiliche siamo noi: io, la Basilica Julia… …e io, la basilica Aemilia – dissero, con voce impastata di sonno, le pietre che restavano del grande e non meno nobile edificio. E io, la basilica di Massenzio – aggiunse con voce cavernosa l’abside del gigantesco rudere, trattenendo a stento un enorme sbadiglio. 27 Era qui che vi volevo. Avete appena nominato l’arco di Costantino. Bene: sappiate che da Costantino in poi noi abbiamo gli stessi diritti nella vostra – nostra città. E Santa Maria Maggiore, affrettandosi prima che si risvegliasse qualcun altro del Foro: Quanto all’eternità, la nostra va ben oltre la vostra. Voi siete eterni nel tempo, ma noi andiamo molto più in là. La nostra eternità dura oltre lo spazio/tempo, in un mondo invisibile e ‘altro’… Mi perdoni, signora – rispose la basilica Julia con tagliente gentilezza – ma, mio malgrado, temo di non poter fare a meno di rilevare che Lei ha pronunciato una serie di emerite sciocchezze. Per cominciare, il tempo è una cosa – irreparabile tempus, et fugit, scrisse il nostro immortale Virgilio (anche se non è così per i monumenti di Roma) – lo spazio, un’altra. Di mondi c’è solo questo, e tutto lo spazio che contiene l’Impero Romano lo ha conquistato. Eppure il mondo in cui noi siamo eterne va oltre la vita, è un mondo di fede – replicò San Giovanni. È un mondo religioso – replicò Santa Maria Maggiore. Ah, mbè, se è tutto qua… – intervenne la Via Sacra – chiamateve un po’ come ve pare, de matti in giro ce ne stanno tanti – io troppi n’ho visti – e le religgioni per noi vanno tutte bene. Non solo era ben decisa a non farsi zittire, ma voleva prendersi la soddisfazione di concludere la disputa e mandare anche un messaggio a quell’insopportabile signora basilica Julia: anche la plebe a Roma aveva il suo comprendonio, i suoi diritti, i suoi tribuni e poteva sentenziare. A meno che…– da dietro Santa Maria Maggiore giunse la voce della Domus Aurea, in un sussurro impastato di sonno. A meno che non siate cristiane – ruggì il Colosseo. – Non sarete mica cristiane, eh? L’hai detto. Siamo cristiane. Abbiamo vinto noi, alla fine – risposero in un unisono trionfale le due basiliche. E non poterono trattenersi dallo sbeffeggiarlo. – Poverino, guardalo, senza leoni, senza gladiatori… 28 …senza sangue cristiano… …senza marmi… …ce li siamo presi tutti noi… … avrai freddo, così nudo… Zitte, voi due. Vergognatevi! – intervenne una terza voce, forte e autorevole anche se veniva da più lontano, oltre il Tevere. Prosegui: E a tutti chiedo un po’ di attenzione. E te’ pareva, eccone n’altra ch’apre bocca e je’ dà fiato. Capirai, hanno detto che so’ sette…, commentò la Via Sacra. Dico anche a te. Sto parlando con tutti. Io sono San Pietro, la Basilica delle Basiliche, e vi chiedo, per favore un po’ di silenzio. – Voglio che capiate. Parlo sul serio, so quel che dico. Le nostre due eternità si conciliano: ascoltate cosa scrisse il Padre Dante, allievo del vostro Virgilio: “Tu dici che di Silvio il parente…” …sarebbe a di’…? – chiese la Via Sacra, ma senza sarcasmo. La basilica Julia alzò un sopracciglio, ma San Pietro capì e rispose con gentilezza. Romolo, il vostro fondatore, ma anche Enea, il nostro legame coi Troiani. Hai ragione, qui non è chiarissimo. Ma riprendiamo: ‘Tu dici che di Silvio il parente / corruttibile ancora, ad immortale / secolo andò, e fu sensibilmente / Però, se l’avversario d’ogne male / cortese i fu, pensando l’alto effetto / ch’uscir dovea di lui e ’l chi e ’l quale…’. …e cioè Roma? – chiese ancora la Via Sacra. Sì, è questo il significato. Andiamo avanti: ‘non pare indegno ad omo d’intelletto: / ch’e’ fu de l’alma Roma e del suo impero / ne l’empireo ciel per padre eletto: / la quale e ’l quale, a voler dir lo vero, / fu stabilita per lo loco santo / u’ siede il successor del maggior Piero’. Nun ce sto’ a capì gnente – commentò la Via Sacra. – Però, se a scrivere è un allievo di Virgilio… …non possiamo che accettarvi – dichiarò solennemente la basilica Julia. Sbadigliò. Gli altri dormivano già tutti di nuovo. 29 The two eternities What time is it? – asked the Basilica Julia in the Roman Forum, yawning and stretching, one eye half open and the other still closed in sleep. I don’t know, – answered the Temple of Castor and Pollux as he extended his three columns in an energetic and healthy after-sleep stretching. I’d say about the sixth hour, but I can’t see any clepsydras around … You fools! It’s a while since clepsydras disappeared! – exclaimed a loud voice from behind the Colosseum. And sundials too! – added an equally robust voice from the opposite direction. Nowadays we look at the time on clocks – the first voice added. Clocks! And them, what’d they be? – asked the Via Sacra, who spoke like a commoner, traveled as she was by thousands and thousands of sandals, some, to be sure, noble and senatorial, but most of them plebeian – even though once the poet Horace had gone there for a quiet stroll but had been disturbed by a crashing bore. The slabs of the Via Sacra had never forgotten this ennobling episode. And in memory of it they tried every now and then to speak “properly” but the experiment rarely succeeded. Clocks are modern machines for measuring time – the first unknown voice explained. – And look at how many there are around our beautiful Rome… You’re right, – the second voice answered – it’s a pity we never really know what time it is. And the first voice retorted, speaking right over the Roman Forum’s head as if it didn’t exist: 31 Well, after all we belong to eternity. Frankly time doesn’t interest us that much. If anything it’s a pity for human beings, for pilgrims. Eternity?? Pilgrims?? – the Rostra asked mockingly. Little remained of the ancient tribune, and the many glorious bow rams seized from Punic ships at Anzio in 338 b.C. had by now disappeared. However the base was still there – strong and solid – and it kept its aggressive nature, which was partly due to having always acted as pulpit, and partly to its indignation over the time when the head of the City’s best orator, Cicero, had been exposed right on the “rostra”, smearing them with his blood. Blood which had also run down the columns, soiling them and even canceling some of the fine images which adorned them. It’s we who are part of eternal Rome – continued the Basilica Julia, speaking hurriedly because she hoped to shut up her gossipy neighbor whom she had never been able to stand, however ancient he might be. He felt so tiresomely linked to the gens Julia because the comitium had placed him so close to her when Caesar had reorganized the Forum. And as if that were not enough, he felt he was the center of the Forum because the circular platform which sustained the “umbilicus Urbis” was just behind him – and that, yes, was the symbolic center of Rome and therefore of the world. So she hurriedly said: We of the Forum are the first to be eternal. And then, of course, the Palatine, the Domus Aurea, the Pyramid, the Colosseum, the arches of Septimius Severus, Titus and Constantine, the Trajan Markets… I mean we Romans. I don’t know whether I’ve made myself clear. The Via Sacra lost her temper: Who d’you think the two of you be? And what th’hell does that ‘ave to do with eternity? Eternity’s ours. Us of Rome, and that’s it. Rome? Of course. My city. I founded it and gave it my name. The voice of Romulus’ Temple reached them from afar and continued: 32 Yes, we drew a square with my brother Remus, but then he died in a mysterious accident. But let’s not stir up the past. Let’s think of our present, and of a glorious future. We’ll conquer the world! War! War, grandchildren of Mars! Let’s go right now to abduct the Sabine women. If the Sabine men rise up, we’ll put them down. Calm down. Take it easy, old King. Go back to sleep – the Basilica Julia answered him so gently that it quite surprised the Via Sacra. Who do we think we are? – the first unknown voice was asking. You mean who are we. I, personally, am Saint John Lateran’s Basilica, the cathedral of Rome… And I’m the Basilica of Saint Mary Major, built exactly on the spot where, in your day, it snowed on the fifth of August. And we’re two of the seven major Roman basilicas… Modestly speaking, two of the finest… Go on with you, insisting on ‘Roman’! – interrupted the Via Sacra. And you even think you’re the cat’s whiskers! But how d’ you get ‘ere? And who knows you anyway? Silence, Via Sacra. Or else speak in language worthy of a constituent member of the Roman Forum – the Basilica Julia interrupted with all the commanding authority of her own nobility. By now she had shrunk, sucked into herself like certain elderly noblewomen: and like them, the more the years devoured her, drying her up and shriveling her like a prune, the more what remained of her marble revealed the blue veins of her “four quarters” of noble blood . She addressed the two invisible voices with affectation and haughtiness: And so there are seven of you. And might I ask you, dear ladies, to tell us who and when, without informing us, granted you the right to call yourselves ‘basilicas’? Because as far as I know (and I venture to say that I, and my senatorial friend Cu33 ria here, right opposite me, know everything there is to know), we are Basilicas: I, the Basilica Julia… …and I, the Basilica Aemilia – the remaining stones of that great and no less noble edifice said in a sleepy voice. And I, the Basilica of Maxentius – the apse of that gigantic ruin added in a cavernous voice, barely holding back a yawn. This is where I wanted to get you. You’ve just mentioned the arch of Constantine. Well: you must know that from Constantine on we have the same rights in your – in our city. And Saint Mary Major hurriedly added before anyone else in the Forum woke up: As for eternity, ours goes way beyond yours. You’re eternal in time, but we go much further. Our eternity lasts beyond space/time, in an invisible and ‘other’ world… Excuse me, madam – the Basilica Julia answered with cutting sweetness – but, in spite of myself, I’m afraid I cannot avoid pointing out that you have just spoken a lot of nonsense. To begin with time is one thing – irreparabile tempus, et fugit, our immortal Virgil wrote (even if this isn’t true of our monuments in Rome) – and space, another. There’s only this world, and the Roman Empire has conquered all the space it contains. And yet the world in which we are eternal goes beyond life, it’s a world of faith – Saint John replied. It’s a religious world – added Saint Mary Major. Oh, cripes, if that’s all it is… – interrupted the Via Sacra. Call yourself whatever you want, there are plenty of madmen around – I’ve seen too many of those – and religions, well, we’ll take them all. – She was not only very determined not to be silenced but she also wanted the satisfaction of concluding the discussion as well as of sending that unbearable lady, the basilica Julia, a message: plebeian Rome too had brains in its head, and rights, and tribunes, and could also pass judgment. Unless… – from behind Saint Mary Major the Domus Aurea’s voice was heard, in a sleepy whisper. 34 Unless you’re christians – roared the Colosseum. – You’re not christians, are you? You’ve said it. We’re christians. We won in the end, – the two basilicas answered triumphantly in unison. And they couldn’t prevent themselves from taunting him: Poor thing, look at him – no lions, no gladiators… …no christian blood… …no marble… …we’ve taken it all… …you must be cold, so naked… Silence you two. Be ashamed of yourselves, – intervened a third voice – loud and authoritative even if it came from further away, beyond the Tiber. It continued: And I ask everyone for a little attention. That’s all we need, here’s another one opening her mouth, sounding her trumpets. Of course, they said they’re seven of them… – commented the Via Sacra. I’m speaking to you too. I’m speaking to everyone. I’m Saint Peter’s, the Basilica of the Basilicas, and I ask you, please, for a little silence. I want you to understand. I’m speaking seriously, I know what I’m saying. Our two eternities are compatible. Listen to what Father Dante, your Virgil’s pupil, wrote: ‘Tu dici che di Silvio il parente…’ Which means…? The Via Sacra asked, but without sarcasm. The Basilica Julia raised an eyebrow, but Saint Peter understood and answered kindly: Romulus your founder, but also Aeneas, our link with the Trojans. You’re right, it isn’t very clear here. But let’s continue: ‘Tu dici che di Silvio il parente / corruttibile ancora, ad immortale / secolo andò, e fu sensibilmente / Però, se l’avversario d’ogne male / cortese i fu, pensando l’alto effetto / ch’uscir dovea di lui e ’l chi e ’l quale…’ …in other words, Rome? – the Via Sacra asked again. Yes, that’s what it means. Let’s go ahead: 35 ‘Non pare indegno ad omo d’intelletto: / ch’e’ fu de l’alma Roma e del suo impero / ne l’empireo ciel per padre eletto: / la quale e ’l quale, a voler dir lo vero, / fu stabilita per lo loco santo / u’ siede il successor del maggior Piero’. I can’t understand a thing he’s saying – the Via Sacra commented. – But if it’s a pupil of Virgil who’s writing… …all we can do is accept you – the Basilica Julia solemnly declared. She yawned. The others were all already asleep again. 36 Africa Un giorno le scimmie ammaestrate scapparono dal circo. Il piccolo babbuino col cappello da ragazzo dell’ascensore aveva sentito parlare di un posto chiamato Africa dall’elefantino nuovo, in groppa al quale doveva fare sei giri di pista. Conosci Africa? – gli aveva chiesto mentre lo alzava con la proboscide e se lo metteva sulla schiena. E, alla risposta negativa, aveva aggiunto: Africa è bellissimo, è pieno di alberi. E sugli alberi ci sono tante scimmie. Stanno su in alto, mangiano banane e si dondolano. Tu come lo sai? Me l’ha detto la mia mamma, prima di partire con l’altro circo. E dov’è? Questo non lo so. Però mi andrebbe di cercarlo. Hmmmm… Il babbuino riferì di Africa al gorilla e al piccolo scimpanzé. Pensa e ripensa, decisero di tentare. Nessuno di loro era molto grande e l’elefantino acconsentì a prenderli tutti e tre sulla schiena. Di notte, insonnoliti, uscirono piano piano dalla tenda a scrisce arancione del circo. Sbucarono in un largo spiazzo asfaltato, solitario sotto la luce violacea di alti fanali. Dallo spiazzo partiva la circonvallazione. L’elefantino si incamminò. Ma era nervoso e spaventato, e procedeva con incertezza. Le tre scimmie accoccolate in groppa ricevevano forti scossoni e si tenevano come potevano. La circonvallazione era percorsa da elefanti di metallo, velocissimi e rumorosi, che li abbagliavano con luci violente. Spesso sfiora39 vano l’elefantino o si fermavano di botto davanti o dietro di lui fra stridori e rumori acuti e spaventosi. L’elefantino deviava a destra e a sinistra e sembrava ubriaco. Era pentito di aver parlato di Africa e di averla voluta cercare. Cominciò a singhiozzare (era un elefantino di pochi mesi): Mamma, mammina, dove sei? E dov’è Africa? Dimmelo, mammina, ti prego. I suoi singhiozzi si traducevano in barriti che provocavano ancora più scompiglio tra i grandi elefanti d’acciaio, rendendoli ancora più cattivi coi loro rumori assordanti e le loro luci accecanti. Sempre più impauriti, in bilico precario sulla sua groppa, il gorilla nano e il piccolo scimpanzé guardavano con crescente disapprovazione il piccolo babbuino col suo berretto gallonato, che aveva insufflato loro quella pessima idea. D’un tratto, davanti all’elefantino si materializzò un elefante metallico molto più grande degli altri. Lo afferrò, lo sollevò con una enorme proboscide dura e gelida, e con lui le tre scimmie, che si grattavano furiosamente. Poi partì, alla solita velocità esagerata. Era un carro attrezzi, e li portò al bioparco. Ormai era l’alba, e la vita ricominciava. C’erano molti alberi. Africa – pensarono le tre scimmie mentre gli inservienti li separavano dalla groppa dell’elefantino. Africa – pensò, consolato, l’elefantino mentre lo conducevano verso un vecchio e solitario elefante indiano. 40 Africa One day the trained monkeys escaped from the circus. The small baboon with the lift boy’s cap had heard the new little elephant, on whose back he was supposed to go around the ring six times, speak of a place called Africa. Do you know Africa? – the baboon had asked the elephant as he lifted him up with his trunk and set him on his back. The answer was “no”, but the elephant added: Africa is beautiful, it’s full of trees. And on the trees there are lots of monkeys. They’re high up, they eat bananas and they rock themselves. How do you know? My mother told me, before she left with the other circus. And where is it? I don’t know. But I’d like to look for it. Hmmmmm… The baboon spoke of Africa to the gorilla and the small chimpanzee. They thought it over and decided to try. None of them were very big and the little elephant agreed to take them all three on his back. By night, half asleep, they quietly slipped out of the orange striped circus tent. They came onto an asphalt esplanade. It was lonely under the purplish light of the high street lamps. The ring road started from the esplanade. The little elephant set out but he was nervous and frightened, and he advanced uncertainly. The three monkeys crouching on his back were rattled around but hung on as best they could. The ring road was full of very noisy metal elephants which moved very fast and blinded them with violent lights. 42 They often barely missed the little elephant or stopped short in front or behind him screeching noisily. The little elephant wavered right and left and seemed drunk. He was sorry he had spoken of Africa and had wanted to look for it. He started to sob (he was only a few months old): Mummy, mummy, where are you? And where’s Africa? Tell me, mummy, please. His sobs came out as trumpeting and this caused even greater confusion among the large steel elephants, making them even nastier with their deafening noises and blinding lights. More and more frightened and precariously balanced on the little elephant’s back, the dwarf gorilla and the small chimpanzee looked at the little baboon under his lift boy’s cap who had given them such a poor idea, with growing disapproval. All of a sudden a metal elephant much larger than the others materialized in front of the little elephant. It seized him, lifted him with an enormous, hard, icy trunk – and with him the three monkeys who were furiously scratching themselves. Then it revved up and set out at its usual exaggerated speed. It was a breakdown truck and it took them to the zoo. By then it was dawn and life was starting up again. There were lots of trees. Africa – thought the three monkeys while the attendants lifted them down from the little elephant’s back. Africa – thought the little elephant, quite consoled, as they led him back to an old and solitary Indian elephant. 43 Congresso Un giorno gli animali si riunirono a congresso per dimostrare che anche loro, e non solo gli uomini, erano capaci di comportamenti culturali. Il consesso si tenne in un’ampia radura, con alberi di varie altezze per uccelli e scimmie, acqua dolce per i pesci di lago e salata per quelli di mare, praterie e savana per erbivori, felini e serpenti, ghiacci per orsi, pinguini e foche, alte vette per le aquile, buchi per le talpe. Alcune vetrine esponevano modellini di oggetti fabbricati dall’uomo, che gli animali avevano imparato ad utilizzare, come porte di case inglesi nella foschia del primo mattino con fuori esposte bottiglie del latte perché gli uccelli di città che avevano imparato a farlo potessero bucarle e succhiare un po’ della bianca bevanda. O ancora, cassonetti della spazzatura di cittadine abruzzesi, in cui sempre più spesso andavano a frugare, per nutrirsi, i lupi del parco nazionale, appunto, d’Abruzzo. E, soprattutto, c’erano oggetti manufatti dagli animali, o loro modellini termitai, autentiche torri del deserto, cunicoli scavati dai lombrichi, dighe di castori, alveari, tele di ragno di varie forme e spessori. Queste ultime erano prive di mosche o altri insetti perché il congresso aveva finalità scientifiche e rigorosamente non predatorie. A tutti, prima della riunione, era stato servito un lauto pasto, e ora i congressisti, in piena digestione, ruminavano, sonnecchiavano, o addirittura dormivano. Qualcuno russava. Le vetrine intanto erano oggetto della meticolosa osservazione di una delegazione di scienziati della razza umana, che erano stati invitati come osservatori e avevano accettato con entusiasmo. 47 Su tutti, di colpo, si levò la voce stentorea del Gufo che, occhialuto e sussiegoso come non mai, presiedeva la riunione dall’alto di una quercia. Buona notte… volevo dire buon giorno a tutti e grazie per essere convenuti qui da tanto lontano. Questo congresso segna l’inizio di una nuova era – che noi proponiamo di chiamare “intraculturale” – e avrà portata storica. Alcuni fra gli esseri umani meno rozzi (i presenti sono sempre esclusi, naturalmente) – qui il gufo fece una breve pausa aspettandosi una risatina di consenso, che però venne solo dalla delegazione di visitatori – stanno cominciando a sospettare che anche fra noi esistano comportamenti sociali e culturali, e capacità di apprendimento. Meglio tardi che mai (e qui la risatina la fece solo lui). Ora, con questa storica riunione, noi vogliamo fare il punto sull’intera questione, di cui peraltro noi tutti eravamo ben consapevoli, e non da oggi. Addirittura, vorremmo dare inizio a una collaborazione intraculturale fra tutte le specie animali del pianeta. Ivi compreso – ed ecco il punto, davvero innovativo se non addirittura rivoluzionario – la specie cui appartengono i nostri visitatori, che per tanto tempo ci hanno ignorato. Siano dunque aperti i lavori. A tutti gli iscritti a parlare verrà data la parola, in ordine di velocità di digestione. Compiaciuta, l’assemblea accolse il discorso con ruggiti, sibili, nitriti, ragli, fischi, borbotti, sbadigli, belati e ululati. Si udì anche un miagolio. La delegazione umana, mettendo da parte i taccuini fitti d’appunti, applaudì con calore. Era davvero una bella giornata, assolata e limpida. Nel cielo terso passò un jet, che però da terra non fu visto data l’incredibile velocità. Si udì solo un rombo terrificante, e poi si vide una scia bianca, lunga come un lunghissimo filo da rammendo, che dopo qualche secondo si ruppe in segmenti, batuffoli bianchi che via via sbiadivano. Il jet al contrario aveva vista acutissima, dotato com’era di strumenti per non perdere un solo dettaglio della superficie che sorvolava. Era un caccia da combattimento di ritorno da una 48 missione. A bordo c’erano due top gun. Uno dei due fu colpito dall’insolito assembramento. Soprattutto perché fra tanti animali – alcuni indiscutibilmente classificati come feroci e pericolosi – c’era, assediato, un gruppetto di esseri umani. Ma quelli sono in pericolo! – gridò nella cuffia il secondo pilota. E non sono armati! Non ce la faranno! Fa un po’ vedere! Dà qua! – rispose il primo, e mise l’occhio nello strumento che l’altro gli porgeva. Tieni tu i comandi, intanto. Porca miseria! No che non sono armati! Quelli non hanno via d’uscita. È una situazione di pericolo doppio rosso! E se l’assedio s’allargasse alla città? – ribadì il secondo pilota. Hai ragione. Urgente limitare danni. Codice ZB54F. Svelto, datti una mossa. Quanti ce ne sono rimasti? Due, signore. Aspetta che viro. Pronto a sganciare? Pronto signore. Ora. Fuori uno. Eseguito, signore. Fuori due. Eseguito, signore. Ben fatto. Bel lavoro. E adesso, andiamo a casa. Da terra, si udì di nuovo il terribile rombo. La scia bianca, però, non fece in tempo a vederla nessuno. Si formò e si decompose mentre dal suolo si innalzavano due colonne di fumo a forma di fungo. 49 Congress One day the animals gathered in congress to show that they too, and not only men, were capable of cultural behavior. The assembly was held in a vast clearing, with trees of varying heights for birds and monkeys, fresh water for lake fish and salt water for sea fish, prairies and savannahs for herbivores, felines and snakes, ice for bears, penguins and seals, high peaks for eagles, burrows for moles. A few show-cases offered models of man-made objects which the animals had learnt to use, such as doors of English houses in the early-morning mist with milk bottles outside so that city birds might make holes in them and suck a little of the white drink. Or else, garbage containers from Abruzzo towns, in which the wolves of the national park of that region scavenged more and more often for food. And, above all, there were objects made by the animals, or their models: termites’ nests (authentic desert towers), underground passages dug by worms, beavers’ dikes, bee-hives, various forms and weights of spider-webs. These latter did not contain flies or other insects because the scope of the congress was scientific and rigorously not predatory. Before the meeting all had been served an abundant meal and now the participants were digesting – ruminating, dozing, or even sleeping. Some were snoring. In the meantime the show-cases were the object of meticulous observation on the part of a delegation of scientists of the human race who had been invited as observers and had enthusiastically accepted. Over all of them, suddenly, the stentorian voice of the Owl 51 rose. Bespectacled and haughty, he presided the meeting from the top of an oak. Good night… I meant to say good day to all, and thank you for having convened from so far away. This congress marks the beginning of a new era – which we propose calling “intra-cultural” and which will be of historical importance. Some of the less uncouth human beings (those present are naturally always excluded) – and here the owl paused briefly, expecting laughter in support of his words which, however, came only from the visitors’ delegation – are beginning to suspect that social and cultural patterns and the ability to learn exist among us too. Better late than never (and here only he laughed). Now, through this historic meeting, we would like to evaluate the entire question, which in fact we have all been well aware of for some time. We would like to start an intra-cultural collaboration between all the animal species of the planet. Including – and here is the truly innovative, if not actually revolutionary, point – the species to which our visitors, who have ignored us for so long, belong. The meeting is open. All those registered to speak will be given the floor in order of speed of digestion. Gratified, the assembly received this speech with roars, hisses, neighing, braying, whistling, muttering, yawns, bleating and howling. Some mewing was heard too. The human delegation set aside its scratch-pads filled with notes and warmly applauded. It was a truly beautiful day – sunny and clear. A jet passed over in the terse sky but was not seen from earth because of its fantastic speed. Only a terrible rumble was heard, and then a white trail – as long as an incredibly long piece of mending thread – appeared only to dissolve into segments, slowly fading white wads. The jet, on the contrary, could see very well because of the instruments it was endowed with so that it would not miss one single detail of the surface it flew over. It was a fighter plane returning from a mission. Two gunmen were on board. One of 52 them was struck by the unusual gathering. Particularly because in the midst of all the animals – some of them unquestionably classified as fierce and dangerous – he could see a group of besieged human beings. But they’re in danger! – the second pilot shouted into the headset. And they’re unarmed! They’ll never make it! Let me see! Give me that! – the first one answered, putting his eye to the instrument the other handed him. – In the meantime you take over the controls. Damn it all! They’re not armed! They have no way out. It’s a high-risk situation! And if the siege spread to the city? – answered the second pilot. You’re right. We must urgently limit the damage. Code ZB54F. Quick, get moving. How many do we have left? Two, sir. Wait till I’ve veered. Are you ready to let go? Ready, sir. Now. Out with one. Order executed, sir. Out with two. Order executed, sir. Well done. Good job. And now let’s go home. The terrible rumble was again heard on earth. Though nobody had time to see the white trail. It formed and dispersed while, from the ground, rose two mushroom-shaped columns of smoke. 53 Comunione “Sarebbe ora di fare il punto”, disse il Punto sbucando dal ventre della Sfera. La Retta stava giocando col Cerchio, indirizzandolo in evoluzioni leggere. Si immobilizzò, sfiorandolo. La Spirale si gonfiò prima al centro poi ai lati, in un respiro-sospiro. Il Quadrato si scisse in due Triangoli Rettangoli. Le Parallele si arrestarono. Tutti prestavano attenzione. Anche il Cilindro e la Piramide, posti a guardia dell’orizzonte, mandarono bagliori. Sì – continuò il Punto – è bello questo nostro trasparente andare per gli spazi, attraverso la caduta degli atomi, fuori del tempo. È bello: ma sento il bisogno di altro. Ci fu una certa confusione. Il Quadrato si ricompose per allungarsi in Rombo. Poi, ritrovata la sua figura, si scisse in due Rettangoli, uno Maggiore e uno Minore, e questi immediatamente in molti Triangoli Isosceli. Il Cerchio si irrigidì in un Ottagono ed emise un Raggio. La Sfera divenne una palla da rugby. È questo che volevi dire? – gridò, mentre rimbalzava irregolarmente. Cilindro e Piramide, dall’Orizzonte, presero a lampeggiare senza interruzione. No – rispose il Punto – non questo. Non so bene cosa sia, ma non mi basto – non ci bastiamo – più. Non vedo un inizio, una fine. In quel momento, la colonna di filigrana degli Atomi in Caduta si inclinò, piegandosi a gomito nel Clinamen. Questo! Era questo che intendevo! – esclamò il Punto. E rideva, come ubriaco. Di colpo si ravvoltolava in una goccia di rugiada, nel cavo di una foglia. Sotto la foglia c’era un prato. 57 Sul prato c’erano alberi e sugli alberi si muovevano a balzi strane figure, con testa, peli, coda e quattro mani. Si servivano di queste mani, fra l’altro, per camminare. Si grattavano, facevano movimenti inconsulti. Squittivano in un baccano caotico, che lasciò esterrefatti i telepatici Naviganti Geometrici, abituati alla melodia delle sfere celesti. Una delle figure a quattro mani, più grande, scura e pelosa, si avvicinò al Punto e lo mangiò. Poco dopo, sugli alberi carichi di banane, il popolo delle scimmie fece una buffonesca e sguaiata comunione, inghiottendo segmenti di Retta e di Parallele, ingozzando i piccoli con bocconi di Cilindro, di Piramide e perfino di Sfera: dopo averla sbatacchiata, erano finalmente riusciti a romperla in mille pezzi come una noce di cocco. Squittivano, inghiottivano, tossivano, esaltati e goffi. Poi, di colpo, fecero silenzio. Scesero compostamente dagli alberi e si avviarono lontano, camminando su due gambe. 58 Communion It’s time to dot the ‘I’ – said the Dot, popping out of the Sphere’s stomach. The Straight Line was playing with the Circle, sending it into light evolutions. The Circle stopped short, brushing against it. The Spiral swelled up first in the middle, then at the sides, breathing and sighing. The Square split into two Right-Angled Triangles. The Parallel Lines stopped short. All listened attentively. The Cylinder and the Pyramid too, who were on guard watching the horizon, sent out flashes. Yes – continued the Dot –This transparent traveling we do through space, through falling atoms, outside time, is lovely, but I feel the need for something else. There was some confusion. The Square recomposed itself to stretch into a rhombus. Then, regaining its original shape, it split into two Rectangles, a Major and a Minor one, and these split immediately into a number of Isosceles Triangles. The Circle stiffened into an Octagon and sent out a Ray. The Sphere became a rugby ball. Is that what you meant? – he shouted as he bounced irregularly. From the Horizon, the Cylinder and Pyramid began to blink uninterruptedly. No – answered the Dot – not that. I don’t really know what it is, but I’m no longer – we’re no longer – enough for ourselves. I don’t see a beginning, an end. At that moment the filigree column of the Falling Atoms tilted, bending sharply in Lucretius’ Clinamen. This! This is what I meant! – exclaimed the Dot. And he laughed as if he were drunk. Suddenly he started wrapping himself up in a dewdrop, in the hollow of a leaf. Under the leaf 60 there was a meadow. On the meadow there were trees and in the trees strange figures with a head, fur, a tail and four hands bounced around. They used these hands, among other things, to walk. They scratched themselves and moved jerkily. They chattered, causing a chaotic hubbub which startled the telepathetic Geometric Navigators who were used to the melody of the celestial spheres. One of the four-handed figures, who was larger than the others and dark and hairy, approached the Dot and ate it. Soon after, on the banana-laden trees, the monkey people partook of a clownish and uncouth communion, swallowing segments of Strait and Parallel Lines and stuffing their little ones with mouthfuls of Cylinder, Pyramid and even of Sphere: after banging it around they had finally succeeded in smashing it like right in the middle with a coconut into a thousand pieces. Exalted and ungainly, they chattered, swallowed, coughed. Then they were suddenly silent. They sedately came down from the trees and moved away, walking on two legs. 61 Football Quando la creazione era giovane (Adamo ed Eva erano ancora nel giardino Terrestre), il mondo era verde come un prato del Tirolo a primavera. Spesso il buon Dio giocava a calcio con gli Angeli. “I miei ragazzi”, li chiamava. Il pallone era in una lega d’argento leggera tanto da non far male ai piedi calzati da sandali anch’essi in argento, ma pesante tanto da rimbalzare e seguire la direzione che il piede gli imprimeva. Le squadre non erano fisse. Si componevano e scomponevano come veniva. Se un Angelo era stanco usciva e ne entrava un altro. Se un Angelo voleva giocare, sbatteva un’ala, un altro Angelo gli cedeva il posto. Gli unici fissi erano i numeri dieci, i capitani: il buon Dio da una parte e Lucifero dall’altra. Naturalmente, quando giocavano contemporaneamente, erano in squadre contrapposte. Le partite si concludevano sempre in parità. Tutti ridevano e si divertivano, trafelati, le guance rosse come ragazzini nel cortile di un seminario. Un giorno Lucifero fece un intervento a gamba tesa sul buon Dio. Non guardò nemmeno dove fosse il pallone, a colpirlo non ci pensò proprio. Il buon Dio non si fece niente perché era il buon Dio, però la cosa non gli piacque. Ehi, tu, bellissimo, cosa credi di fare? Non è così che si gioca. Non è sportivo. Scusa, ho sbagliato. L’incidente però si ripeté due o tre volte: troppe perché il buon Dio alla fine lasciasse correre, o continuasse ad accontentarsi di qualche scusa borbottata fra i denti. Quando si stancarono di giocare, e i giocatori si sedettero sull’erba o si dispersero dolcemente in volo, lo chiamò in disparte. 65 Ma insomma, Lucifero, dove vuoi arrivare, si può sapere? A vincere. A “vincere”? Ma “vincere” e “perdere” sono parole che non fanno parte di questo mondo perfetto. Noi giochiamo per la gioia di giocare, non perché alla fine ci sia chi trionfa e chi è umiliato. Per questo è tanto noioso. Io di questa perpetua parità non ne posso più. E ti dirò, caro amico, ti dirò: non solo voglio vincere, ma voglio un torneo. Il buon Dio era così esterrefatto da lasciar correre nell’espressione “caro amico”, che nessuno, mai, aveva usato prima di quella volta. Squadre fisse?? Un torneo?? Ma sei fuori di testa? E voglio anche degli arbitri, che segnino i punti. Punti?? Ma ti rendi conto che così si costituirà per forza una gerarchia di giocatori e di squadre? Gli angeli più agili giocherebbero nelle squadre più forti, gli altri nelle meno forti. Si verrebbero a formare addirittura una serie A e una serie B. Tutto quello che io non voglio. Qui siamo tutti liberi ed euguali. Meno te. Tu sei un po’ più libero e un po’ più euguale degli altri, no? O mi sbaglio? Come osi? Sono io che vi ho creato. Io sono il Re perché sono vostro padre. Beh, io sono un figlio cresciuto. E sono repubblicano. Il buon Dio era allibito. Guardò negli occhi questo figlio prediletto: il più bello, il più intelligente, il più aitante, il più simpatico, quello che lui stesso aveva voluto capitano dell’altra squadra. L’altro sostenne lo sguardo divino, interrogativo, ansioso, e quasi presago di rovina, con occhio torvo e duro. Nemmeno questa espressione lì si era mai vista. Che sciocco sono stato – mormorò a se stesso il buon Dio. Non tanto piano però che l’altro non sentisse. Sciocco, sì, e poco previdente. Hai pensato che bastassero le tue intenzioni a bloccare il futuro? A fermare la dialettica? Sì, è vero che sei stato audace a creare tutto questo. Si guardò intor66 no nello splendore dell’erba, nel cielo blu cobalto dove molti suoi fratelli volteggiavano con grazia di aironi. Sì, è vero, hai voluto dar vita alle cose, ma non hai pensato che le cose si trasformano. Tu non sei una cosa. Sei un essere eterno, sopra le cose, come me. Fatto per l’immortalità e la perfezione di un mondo in cui il tempo non scorre e non brucia tutto. Ma io ne ho abbastanza di questa immobilità. Voglio il cambiamento, il movimento. Voglio la storia. E con la storia verrà la guerra… la violenza … il sangue… La morte. E allora? Sì, è questo che voglio vedere, a questo partecipare. Voglio eserciti, gare, gerarchie. Voglio primi e ultimi, potenti e miserabili, poveri e ricchi e fatica, e scorciatoie (magari disoneste) per abbreviare il salto da una posizione all’altra. Dunque anche rubare, uccidere il proprio vicino… Sì, certo. È lo scenario a cui voglio assistere. Uno scenario vivo, intelligente, non immobile e finto in cui tu vuoi bearti. Ha ragione! Anche noi vogliamo questo! Un torneo! Vincere e perdere! Mentre il buon Dio taceva, sempre più pallido e sgomento, un nucleo di Angeli, mano a mano che i due parlavano, gli erano planati intorno. Si erano schierati dalla parte di Lucifero, e cominciavano a formare una piccola folla, e mano a mano che quello parlava sbattevano rumorosamente le ali. E intervenivano a rincarare la dose. Primi e ultimi! Poveri e ricchi! Vogliamo il denaro. …per dare valore alle cose. …per comprarle… Per vedere l’uso che se ne fa… …Come lo si guadagna… …come lo si perde… 67 Dall’alto, anche Gabriele e Raffaele videro quell’assembramento, udirono le voci concitate, e scesero a piazzarsi saldamente alle spalle del buon Dio, come a fargli da guardia. Gli altri Angeli, ignari, continuavano a volteggiare fra sorrisi e piccole grida di felicità. Rimasero sorpresi, però, nel vedere qualche nube che si avvicinava. Nuvole, fino ad allora, non se ne erano mai viste nel Regno Celeste; ora, invece, stavano assembrandosi, stavano coprendo l’orizzonte. Scesero anche loro, spauriti: un sentimento nuovo, che non conoscevano. Si misero a guardare la scena, uno accanto all’altro, stretti come per farsi coraggio. Una premonizione oscura (nuova anche questa) diceva loro che qualcosa di terribile stava per accadere, separando il “prima” dal “poi” (terza cosa di cui non conoscevano il significato). E infatti accadde. Il buon Dio lasciò che i protestatari parlassero tutti, nessuno escluso. Poi tacque: un silenzio che parve non finire mai. E anche la durata e l’attesa erano sensazioni che non avevano mai privato. Finalmente il buon Dio parlò. Era più alto e più grande. Sei sicuro Lucifero, di volere quello che hai chiesto? Io non l’ho chiesto. Non ho niente da chiedere a te. Io semplicemente lo pretendo. Si capisce che sono sicuro. Ci ho pensato, sai? E sai che sono intelligente. L’intelligenza non è tutto. A volte, anzi, è dannosa. Oh! Beh, se ce l’hai la usi. E se la usi troppo, l’intelligenza provoca ambizione, e l’ambizione disamore per il prossimo. Chiamalo pure odio. Non mi fa paura un sentimento forte in tanta bambagia. Il buon Dio avvampò. Mormorò fra sé: Ti avevo fatto per la felicità e per l’amore… Ma si riprese in tutta la sua maestà. Anche la sua voce suonava diversa, ora mandava un’eco di bronzo. Chiese ai seguaci di Lucifero: 68 E voi altri, siete sicuri di quel che dite? Di quello che volete? Badate, non sarà senza conseguenze. Si fece un gran silenzio. Raffaele e Gabriele, alle spalle del buon Dio, avevano spalancato le ali e, all’improvviso, sguainato la spada lucente. Gli angeli spettatori erano fermi anche loro, atterriti. Sembravano rimpiccioliti. I seguaci di Lucifero, immobili dietro di lui, per la prima volta avevano un’espressione torva, la stessa del loro capo, come in quei luoghi non si era mai visto. Per loro rispose Lucifero: Certo che sono sicuri. Sono miei, te li ho rubati. Ma il buon Dio insisté: E voi non sapete più parlare? Non avete da replicare con la vostra lingua? Silenzio. Allora il buon Dio divenne enorme. Con la testa toccava il cielo sempre più buio. Si levò un forte vento di ostro, che soffiando portava angoscia. Poi cominciò a grandinare, così fitto che il mondo si oscurava sempre di più. E l’Onnipotente parlò, con la sua voce bronzea che risuonava al di sopra del vento e della grandine, e oltrepassava i quattro angoli dell’orizzonte: Da questo momento, Lucifero, figlio mio prediletto, non sarai più mio figlio. Né lo sarà la tua banda di seguaci. Io vi tolgo le ali. Le ali caddero all’unisono sull’erba bagnata. Martellate dalla grandine, quelle piume una volta soffici e lievi si infradiciarono, trasformandosi in straccetti grigi, che il vento muoveva qua e là come cartacce. Non potrai più volare, nemmeno con la mente. La mente però te la lascio, per covare pensieri bassi, e perché capisca meglio la tua disgrazia e la tua sofferenza. Lo stesso vale per voi, aggiunse rivolto agli altri angeli, che ora sembravano nudi e infreddoliti come esseri umani in una tempesta. Vi maledico, tutti, e vi scaccio dalla mia dimora. E ora cadete, cadete, cadete. Sprofonderete tanto in basso che nemmeno 69 la tua mente, Lucifero, sarà in grado di capire dove sarete quando vorrò che vi fermiate. Di lì non potrete risalire. Non rivedrete il volto di chi un giorno fu vostro padre. Mai più. Andate, ora, al destino che avete scelto. Una voragine si aprì nell’erba fradicia sotto i piedi di Lucifero allargandosi ai piedi dei suoi seguaci. Alcuni di essi singhiozzavano, e gridavano: Perdonaci, padre. Chiamaci di nuovo a te. Per tre di loro la terra non si aprì, ed essi caddero in ginocchio nella grandine, tra gli sberleffi degli altri, sotto i quali il vuoto si propagava come un’onda, e non si fermò finché non li ebbe inghiottiti tutti. Poi si richiuse. L’erba folta spuntò di nuovo, e d’incanto fu verde e rugiadosa. La grandine si fermò, le nuvole si ritirarono e sparirono, l’ostro si trasformò in una leggera brezza di maestrale. Gabriele e Raffaele erano ancora immobili ai loro posti, ma reinguainarono le spade. Gli angeli spettatori tirarono un respiro di sollievo. Le ali di tutti erano asciutte e nivee. Amen, dissero a una voce Gabriele e Raffaele. Amen, disse il buon Dio. Ma la sua voce per la prima volta era triste. L’incanto era rotto. Gli uomini, da quel momento, non avrebbero fatto che sognarlo. E Lucifero avrebbe insanguinato le loro utopie. 70 Football When creation was young (Adam and Eve were still in the Garden of Eden), the world was as green as a Tyrolean meadow in spring. The good Lord often played football with the angels. “My boys”, he called them. The ball was made of a silver alloy so light that it would not hurt their sandaled feet (the sandals too were of silver) but just heavy enough to bounce and follow the direction the foot gave it. The teams varied. They were formed and dissolved as the case might be. If an Angel was tired he left the field and another went in. If an Angel wanted to play, he flapped a wing and another Angel gave him his place. The only fixed players were the captains – the ‘number tens’: the good Lord of one team and Lucifer of the other. Naturally, when they played together their teams were opposed. The games always ended in a draw. Everyone laughed and had fun, panting like pink-cheeked children in a seminary courtyard. One day Lucifer tripped up the good Lord. He didn’t even look where the ball was. He had no intention of kicking it. The good Lord was unhurt because he was the good Lord, but he didn’t like it. Hey, you, dandy, what d’you think you’re doing? That’s not the way to play. It’s unsporting. Sorry, I made a mistake. But the same incident recurred two or three times: too many for the good Lord to close an eye or continue to be satisfied with a few muttered apologies. When they were tired of playing and the players sat down on the grass or gently flew away he called Lucifer aside. 72 Come on, Lucifer, might I know what you’re getting at? I want to win. To “win”? But “winning” and “losing” are words which don’t belong in this perfect world. We play for the joy of playing and not because, at the end, some of us are triumphant and others humiliated. That’s why it’s so boring. I can’t stand these perpetual draws any longer. And, dear friend, let me tell you that not only do I want to win but I also want a tournament. The good Lord was so astounded that he didn’t even react to the expression “dear friend”, which nobody had ever used before. Fixed teams?? A tournament?? Are you out of your head? And I also want umpires, to keep track of the score. Score? But do you realize that in this way, whether we like it or not, we’ll have a hierarchy of players and teams ? The more agile angels would play in the stronger teams, the others in the weaker ones. We would even come to have an A series and a B series. Everything I don’t want. We’re all free and equal here. Except for you. You’re a little more equal and a little more free than the others, aren’t you? Or am I mistaken? How dare you? It’s I who created you. I’m the King because I’m your father. Well, I’m a grown-up son. And I’m republican. The good Lord was taken aback. He looked in the eyes of this favourite son: the most handsome, the most intelligent, the most vigorous, the most attractive, the one he himself had wanted as captain of the other team. Lucifer was unabashed by the divine gaze – which was questioning, anxious and almost a prediction of ruin – and returned a hard and surly look. This expression too had never been seen there. How stupid I’ve been – the good Lord muttered to himself. But not so low as not to be heard by Lucifer. Yes, stupid, and not very far-sighted. You thought that your intentions were enough to block the future? To stop dialectics? 73 Yes, it’s true that it was daring of you to create all this. He looked around: at the splendour of the grass, at the cobalt-blue sky where many of his brothers were wheeling with the grace of herons. Yes, it’s true, you wanted to give life to things, but you didn’t think that things transform themselves. You’re not a thing. You’re an eternal being, you’re above things, like me. Made for the immortality and perfection of a world where time doesn’t flow and everything doesn’t burn up. But I’m sick and tired of this immobility. I want change, movement. I want history. And war… violence… blood… will come with history. And death. And so what? Yes, that’s what I want to see and take part in. I want armies, contests, hierarchies. I want the first and the last, the powerful and the weak, the poor and the rich and toil, and short-cuts (possibly dishonest ones) to shorten the gap between one position and the next. You mean stealing too, and killing your neighbour… Yes, of course. That’s the setting I want to see. A living, intelligent scene, not like the motionless and artificial one you want to enjoy. He’s right! We want this too! A tournament! Winning and losing! Paler and paler and more and more dismayed, the good Lord remained silent, while a nucleus of Angels glided around him as they talked. They had taken Lucifer’s side and were beginning to form a small crowd, loudly flapping their wings. And they interrupted, making things worse. The first and the last! Poor and rich! We want money …to give things their value …to buy them… To see how it’s used… 74 How one earns it… …how one loses it… From above, Gabriel and Raphael too saw the crowd, heard the excited voices, and came down to place themselves firmly behind the good Lord as if to watch over him. The other Angels, unaware of their presence, continued to circle around, smiling and letting out small shrieks of happiness. They were surprised, however, to see a few clouds drawing closer. Until then clouds had never been seen in the Celestial Kingdom. Now, instead, they were gathering and covering the horizon. They too alighted and were afraid: fear was a new feeling they had yet to experience. They started watching the scene, huddled together as if to pluck up their courage. A dark premonition (this too was new) told them that something terrible was about to happen which would separate “before” from “after” (they didn’t know the meaning of this third word either). And in fact it did happen. The good Lord allowed all the protesters to speak. No-one was excluded. Then he was silent: a silence which seemed unending (waiting and expectancy were sensations they had never experienced either). Finally he spoke: He was taller and bigger. Are you sure, Lucifer, that you want what you asked for? I didn’t ask for it. I have nothing to ask of you. I’m simply claiming it. Of course I’m sure. I’ve thought about it, you know. And you know I’m intelligent Intelligence isn’t everything. Sometimes it’s even harmful. Oh, well! If one has it one uses it. And if you use it too much, intelligence provokes ambition, and ambition prevents us from loving our neighbour. Call it hatred if you want. A strong sentiment doesn’t frighten me in all this cotton wool. The good Lord turned red. He murmured to himself: I made you for happiness and love… 75 But he recovered all his majesty. His voice too had a different ring, now it echoed like bronze. He asked Lucifer’s followers: And the rest of you, are you certain of what you’re saying? Of what you want? Be careful for it won’t be without consequences. There was a great silence. Raphael and Gabriel, standing behind the good Lord, had spread their wings and suddenly unsheathed their shining swords. The spectator angels too were still and terrified. They seemed to have grown smaller. Lucifer’s followers, motionless behind him, wore grim expressions for the first time, like their leader, – expressions such as had never before been seen in those places. Lucifer answered for them: Of course they’re certain. They’re mine, I stole them from you. But the good Lord insisted: And don’t you know how to speak any more? Can’t you answer with your own tongues? Silence. Then the good Lord grew immense. His head reached the darkening sky. A strong westerly wind rose, carrying ‘angst’ with it as it blew. And it started to hail so heavily that the world grew darker and darker. And the Omnipotent spoke, in his bronze voice which echoed above the wind and hail and reached beyond the four corners of the horizon. From this moment Lucifer, my favourite son, will no longer be my son. Nor will your band of followers. I deprive you of your wings – and their wings fell in unison onto the wet grass. Battered by the hail, the once soft and delicate feathers got drenched and became little grey rags which the wind blew here and there like waste paper. You will never be able to soar again, not even with your mind. However I’m leaving you your mind to brood over base thoughts, and so that you may understand better your disgrace and suffering. The same holds for you, he added turning to the 76 other angels, who now seemed naked and chilled like human beings in a storm. I curse you, all of you, and banish you from my dwelling. And now fall, fall, fall. You will sink so low that not even your mind, Lucifer, will be able to understand where you are when I shall want you to stop. From there you won’t be able to come up again. You’ll never again see the face of he who once was your father. Never again. Go, now, to the destiny you have chosen. A chasm opened in the wet grass under Lucifer’s feet, widening under his followers’ feet. Some of them sobbed and shouted: Forgive us, father. Call us back to you. For three of them the earth didn’t open and they fell on their knees in the hail, taunted by the others under whom the emptiness spread like a wave and didn’t stop until it had swallowed them all. Then it closed. The thick grass appeared again and, as if by magic, grew green and dewy. The hail stopped, the clouds drew back and disappeared, the western gale became a gentle north-westerly breeze. Gabriel and Raphael had remained motionless in their places, but now they sheathed their swords. The spectator angels drew a sigh of relief. Everyone’s wings were dry and snowy white. Amen, Gabriel and Raphael said with one voice. Amen, said the good Lord. But for the first time his voice was sad. The spell was broken. From then on, men would do nothing but dream of it. And Lucifer would bloody their utopias. 77 Aut… aut Aut… aut! – gridò Lucifero mentre precipitava. La sua bellezza splendeva ancora, ma si faceva sempre più livida via via che si allontanava nell’ombra. La spada gliela aveva tolta Gabriele, che ora la roteava in alto. Lucifero aggiunse una selva di parole, simili a imprecazioni, incomprensibili all’angelo alato. Le scaraventò fuori dalla bocca come sassi: Enten… eller! either…or! oder…oder! où…où! Sì, cuccù!… Ci prendi in giro? gli rispose Gabriele. E Raffaele rincarò: O cominci a non sapere più sillabare la lingua celeste? No, tacete. Sa quel che dice, intervenne il Buon Dio. E all’angelo che stava cadendo domandò: Che vuoi dire? Spiegati meglio. Fece un cenno. Lucifero si arrestò a mezz’aria. Rispose: Voglio dire, mio caro, che questa è la mia vendetta: ti porterò via molte anime. Saranno o bianche o nere: le bianche a te, ma le nere me le prenderò io. Che enormità – rispose il Buon Dio. – Le anime non sono mai tutte d’un colore. Spesso sono grigie, oppure hanno colori diversi, in contrasto l’uno con l’altro. Rubano ma amano la musica, mentono ma fanno l’elemosina. Oh, sì, certo: vedrai, vedrai. Metti l’occhio nel futuro. Su, da bravo, fallo: e dimmi cosa vedi. Cosa fanno, i tuoi meravigliosi esseri umani, come si comportano? Non sono forse ruffiani, violenti, ladri, mafiosi…? Il Buon Dio taceva. Coraggio, coraggio – incalzò Lucifero. – Guarda e dimmi cosa ti appare. 81 Non ho bisogno di guardare. Dimentichi che sono onnisciente? Oh, certo. E poi, per mia fortuna, hai dato loro il libero arbitrio… Lucifero ridacchiava. Angeli e Arcangeli, intorno al Buon Dio, d’istinto avevano chiuso le ali e deposto le spade per ascoltare con più attenzione. Non c’è niente da ridere. Il libero arbitrio è una delle cose più serie della Creazione – rispose il Buon Dio – Certo che so di quali istinti negativi e passioni possano essere preda gli esseri umani ma, vedi, sono complessi. Sono umani. Uccidono il vicino, ma sono teneri con il figlio. Sono gelosi ma anche generosi. Amano e odiano. Sono contraddittori. Io li avevo fatti semplici, ma da quando ho dovuto scacciare quei due dal Giardino dell’Eden la vita per loro è diventata dura. Mai quanto la mia – borbottò Lucifero. Ma il Buon Dio continuò. Io lo so bene: sono io che gliel’ho imposta. È una vita che costringe a contraddizioni continue per trovare un equilibrio, o almeno la sopravvivenza. D’altronde sono stati loro a scegliere la complessità, e ormai mi sono cari lo stesso. Dovranno lottare e pagare, ma restano mie creature. Angeli e Arcangeli respirarono al termine di questo lungo discorso, e fu come se un fremito percorresse il loro cerchio alato. Il Buon Dio disse, ancora: No, Lucifero, no: ‘aut…aut’ non sarà mai la mia legge. È riduttiva e restrittiva, e al fondo contiene una trappola. Non c’è amore, in ‘aut…aut’. E perché dovrebbe essercene? Io li odio tutti. Ma io li amo. Sì, sì, li hai fatti tu, lo sappiamo. E allora non dimenticarlo. Mia è la legge suprema, e questa legge è ‘e…e’. Perché una scelta non deve escluderne necessariamente un’altra. Perché possono esserci tante risposte ad una stessa domanda: tutte valide, e magari in contrasto fra loro. E 82 io non voglio che si eliminino a vicenda solo perché, per il momento, la mente umana non è ancora in grado di sopportare risposte il cui spessore vada oltre la linearità della logica che ha appena conquistato. Gli uomini sono complessi e largamente inconsapevoli, ma anche l’universo è complesso. E la mia legge permetterà, col tempo, una ricca e felice evoluzione umana. Il respiro di Angeli e Arcangeli costituiva una lievissima melodia che accompagnava armonicamente le parole del Buon Dio, e le completava. Lucifero ne percepì la dolcezza, e ne fu indispettito. Ma che quadretto commovente…! Che bel Lieto Fine…! e poi, ricordiamolo, per gli esseri umani c’è sempre il pentimento: proprio una bella scappatoia. Non è una scappatoia, Lucifero. Pentirsi e perdonare sono due prove tra le più difficili che, uscita dal Giardino, l’umanità ha avuto in dono la possibilità di affrontare. ‘In dono’, poi… che modo ipocrita di esprimersi: E che razza di dono sarebbe? Un dono che comporta viaggi all’interno di se stessi tempestosi ma pacificatori. Un dono che permette – a chi ne abbia il coraggio – di attingere a quelle segrete ragioni del cuore che la ragione del sillogismo non saprà mai cosa siano. Splendido. Per me, comunque, non cambia niente: la mia legge rimane ‘o…o’, ‘aut…aut’. Ma non vedi quanto è restrittiva? E noiosa, per giunta. O pace o guerra, o buoni o cattivi, nessuno spazio per la mediazione, per la molteplicità… È… intellettualistica, aperta alle mille capziosità dei legulei… Legulei, sofisti… giocolieri dell’intelletto. Come li amo. È proprio questa la gente che voglio, caro il mio bravo Maestro. E tu ti ci dovrai adattare. Non mi ci hai voluto a comandare con te. Sei tu che non hai voluto accettare di essere, come tutto e tutti, una mia creatura. E la tua infinita generosità? E la tua capacità di perdonare? Anch’io sono complesso, sai… 83 No, Lucifero. Tu sei semplice. Volevi il potere senza l’amore. E questo non era nella mia natura poterlo accettare. Mi hai scacciato, infatti. Sai essere poco tenero anche tu, quando ti ci metti. Come osi parlarmi così? Io sono l’Onnipotente… Angeli e Arcangeli aprirono le ali e si strinsero in un cerchio ancora più serrato intorno al Buon Dio. Ma questo non impedì alla voce stentorea di Lucifero di superarne la barriera: Lo eri, caro, lo eri. Non lo sei più. Di colpo, perso ogni controllo, si mise ad urlare: NON SEI PIÙ ONNIPOTENTE , CAPITO ? SIAMO IN DUE , ADESSO . TE LO VUOI FICCARE IN TESTA SÌ O NO ? NON AVRAI PIÙ SCELTA , D ’ ORA IN AVANTI . Un brivido di minaccia percorse il cerchio alato delle guardie tutt’intorno al Buon Dio. Lucifero lo percepì e abbassò il tono di voce, ma continuò: Adesso dovrai adattartici alla mia presenza. Non dipende più da te. Ci ho pensato, sai. E mi sono reso conto che hai un solo lato debole: non sai resistere all’imbarbarimento. Così ti ho attaccato da quella parte: e io il tuo bell’‘e…e’ te l’ho tolto. D’ora in poi – anche per te – la tua legge dovrà piegarsi alla mia: ‘aut…aut’. Non puoi farlo. Non puoi davvero volere livellare tutto in basso… Angeli e Arcangeli raccolsero le spade. Ma Lucifero, sospeso e fermo nel buco per magia divina, si fregava le mani. Sì che posso. Posso e voglio. Ho appena detto che non sei in grado di resistere alla barbarie, no? E avevo ragione, a giudicare da come reagisci. Per la prima volta dai suoi splendidi occhi si sprigionò uno sguardo non solo malevolo, ma capace – lo si capiva – di incenerire. E vedrai, caro il mio primo della classe, vedrai quanti pigri e miopi mi seguiranno. A legioni saranno attratti da guadagni facili, dal tutto-e-subito, incuranti e forse anche compiaciuti di 84 corrompere irrimediabilmente il bel mondo che tu ti sei illuso di crea… “Vai, sciagurato!” – gridò allora il Buon Dio, tagliandogli la frase in bocca. Mosse un dito, e Lucifero riprese la sua folle discesa verso gli inferi. Angeli e Arcangeli, ad ali spalancate, si erano chinati sul pozzo, come a coprirlo, e vi incrociavano sopra le spade. Ma la loro lealtà non bastò a lenire il dolore di una trafittura che il Buon Dio avvertiva nel suo cuore, proprio al centro. Una freccia aveva colpito il bersaglio, e vi era penetrata così a fondo che sarebbe stato impossibile rimuoverla. Così, mentre il suo avversario, condannato, precipitava sempre più in fondo, il Buon Dio si sentì costretto – sì, costretto – a fare una legge. Prendi una tavola da incidere – disse a Gabriele. Per la prima volta, i suoi modi furono bruschi. In silenzio, fra Angeli e Arcangeli intimiditi e frastornati, dettò i Dieci Comandamenti. Gabriele li incideva, adagio. Non aveva ancora tanta pratica di alfabeti. Il Buon Dio dettava a raffica: Io sono il Signore Dio tuo, primo, non avrai altro Dio fuori di me… Gabriele sudava, la lingua fra i denti. Sbrigati – gli disse, imperativo, il Buon Dio. Subito dopo, si fece accompagnare da lui giù da Mosè a consegnargli le Tavole. Gabriele gli stava accanto, invisibile, arruffato e preoccupato. Fate come vi dico – ordinò il Buon Dio a Mosè, apparendogli in veste terrificante. Fatelo, o altrimenti… Sparì… Non avrebbe mai voluto che Mosè lo vedesse con gli occhi pieni di lacrime, ferito, appoggiato a un’ala di Gabriele. Scusami – gli sussurrò. Gabriele lo abbracciò con le ali e lo riportò su. Il Buon Dio seppe che da quel momento, più si fosse sentito fragile, solo e malinconico, più avrebbe dovuto mostrare un 85 volto terribile e temibile. Aveva perso. Aveva dovuto piegarsi alla legge dell’‘aut…aut’. Colpa sua? Dove aveva sbagliato con Lucifero? O forse non aveva sbagliato, e semplicemente non c’era niente da fare? Comunque, la vendetta del figlio ribelle cominciava a divenire realtà, e per lui non c’era un altro Buon Dio. O forse ce ne era uno, ma non era Buono. 86 Either … or! Either… or! – shouted Lucifer as he fell. His beauty still shone but it was waning as he dropped further and further into the shadow. Gabriel had taken his sword away and was whirling it up high. Lucifer added a stream of oath-like words, but the winged angel found them incomprehensible. Lucifer hurled them from his mouth like stones. Enten…eller! Either…or! Oder…oder! Où…où! Gabriel answered: Yes, cuckoo!… Are you taking us for a ride? And Raphael added: Or… can’t you speak the celestial language any longer? No, be quiet – the Good Lord intervened, – He knows what he’s saying. And he asked the falling angel: What are you trying to say? Be clearer. He waved his hand. Lucifer stopped in mid-air and answered: I want to say, my dear fellow, that this is my revenge: I’ll steal a great many souls from you. They’ll be either white or black: the white ones for you, but I’ll take the black ones. How outrageous – the Good Lord answered. – Souls are never all one color. Often they’re grey or have different colors, in contrast with one other. They steal but they love music, they lie but they give alms. Oh, yes, sure: you’ll see, you’ll see. Put your eye to the future. Come on, be a good fellow, do: and tell me what you see. What are they doing, your wonderful human beings, how are they behaving? Aren’t they all toadies, berserkers, thiefs and members of the mafia …? 88 The Good Lord was silent. Don’t be afraid, speak up – Lucifer urged him. – Look and tell me what you see. I don’t need to look. Have you forgotten that I’m omniscient? Oh, of course. And besides, for my good fortune, you gave them free will… Lucifer was sniggling. The Angels and Archangels around the Good Lord had instinctively closed their wings and put down their swords to listen more carefully. There’s nothing to laugh about. Free will is one of the most serious things of Creation – the Good Lord answered. – Of course I know what negative instincts and passions human beings can be prey to. But, you see, they’re complex. They’re human. They kill their neighbor, but they’re tender with their children. They’re jealous but they’re also generous. They love and hate. They’re contradictory. I made them simple, but since I had to drive out those two from the Garden of Eden life has become hard for them. Never as hard as mine – muttered Lucifer. But the Good Lord continued: I know perfectly well: it’s I who imposed it on them. It’s a life which forces constant contradictions on them so that they may find a balance or at least survive. On the other hand it’s they who chose complexity, and by now they’re dear to me all the same. They’ll have to struggle and pay, but they’re still my creatures. The Angels and Archangels breathed again at the end of this long speech and it was as if a shiver ran through their winged circle. The Good Lord added: No, Lucifer, no: ‘either…or’ will never be my law. It’s reductive and restrictive, and it hides a trap at the end. There’s no love in ‘either…or’. And why should there be? I hate them all. 89 But I love them. Yes, yes, you made them all, we know that. Then don’t forget it. The law is mine and it’s supreme, and this law is ‘and…and’… Because one choice doesn’t have to exclude another. Because there can be many answers to the same question: all of them valid, and possibly contrasting. And I don’t want them to eliminate one another simply because, right now, the human mind isn’t yet able to bear with answers whose breadth goes beyond the linearity of the logic it has only just conquered. Men are complex and hugely unaware, but the universe too is complex. And, in time, my law will allow for a full and happy human evolution. The Angels’ and Archangels’ breathing produced the faintest of melodies which harmoniously accompanied and completed the Good Lord’s words. Lucifer felt its sweetness and was irritated by it. What a moving picture…! What a Happy Ending…! And then, let’s remember, for human beings there’s always repentance: an easy way out. It isn’t a way out, Lucifer. Repentance and forgiveness are two of the most difficult tests humanity was granted the possibility of facing after it left the Garden. ‘Granted as a gift’… what a hypocritical form of expression: And what kind of a gift would that be? A gift which involves stormy but pacifying journeys within oneself. A gift which allows those who are courageous enough to draw on those secret reasons of the heart which the reasons of syllogism will never be able to fathom. Splendid. For me, however, this doesn’t change anything: my law remains ‘either…or’, ‘aut… aut’. But can’t you see how limiting it is?…and boring. Either peace or war, either good or bad, no space for mediation, for multiplicity. It’s intellectualistic, open to every kind of pettifogger captiousness… Pettifoggers, sophists… jugglers of the intellect. How I love 90 them. Those are precisely the people I want, my dear good Master. And you’ll have to adapt to it. You didn’t want me to share commanding with you. It’s you who didn’t want to accept being a creature of mine – as everything and everyone else did. And your infinite generosity? And your capacity for forgiveness? I too am a complex being, you know. No, Lucifer. You’re simple. You wanted power without love. And it wasn’t in my nature to accept this. In fact you threw me out. When you get going, your tenderness goes out of the back door. How dare you speak to me like that? I’m the Omnipotent One… The Angels and Archangels opened their wings and compacted their circle around the Good Lord. But this didn’t prevent Lucifer’s stentorian voice from overcoming the barrier: You were, my dear fellow, you were. But you aren’t any longer. Suddenly he lost all control and started shouting: YOU ’ RE NO LONGER OMNIPOTENT, DO YOU UNDER STAND ? THERE ARE TWO OF US NOW. DO YOU WANT TO GET THIS INTO YOUR HEAD , YES OR NO ? FROM NOW ON YOU HAVE NO CHOICE . A menacing shiver ran through the winged circle of guards around the Good Lord. Lucifer sensed this and lowered his tone of voice. But he continued: Now you’ll have to adapt to my presence. It no longer depends on you. I’ve thought about it, you know. And I realized that you have only one weak side: you don’t know how to resist against barbarization. And so I attacked you on that side: I’ve taken away your fine ‘and…and’. From now on – for you too – your law will have to bow down to mine: ‘either…or’. You can’t do that. You can’t really want to level everything downwards… The Angels and Archangels picked up their swords. But Lu91 cifer, by divine magic suspended and immobile in the hole, rubbed his hands together. Yes I can. I can and I want to. I’ve just said that you’re unable to resist barbarity, haven’t I? And I was right, to judge from your reaction. For the first time his splendid eyes sent forth a piercing look. It was not only malevolent but clearly capable of incinerating too. And you’ll see, my dear ‘top of the class’, you’ll see how many lazy and short-sighted people will follow me. They’ll be attracted in legions by easy gain, by ‘everything-right-now’, indifferent to and possibly even pleased at the idea of irremediably corrupting the fine world you were under the illusion of crea… At this point the Good Lord interrupted his sentence in mid air and shouted – Go, wretch! He moved a finger and Lucifer resumed his wild fall towards hell. With widespread wings, the Angels and Archangels bent over the well as if to cover it and crossed their swords over it. But their loyalty was not enough to soothe the pain of a stab the Good Lord felt right in the middle of his heart. An arrow had struck the mark and had penetrated so deeply that it would have been impossible to remove it. So, while his condemned adversary precipitated deeper and deeper, the Good Lord felt obliged – yes, obliged – to formulate a law. Take a tablet and write – he said to Gabriel. For the first time he spoke curtly. In silence, surrounded by the intimidated and bewildered Angels and Archangels, he dictated the Ten Commandments. Gabriel impressed them, slowly. He wasn’t very used to alphabets. The Good Lord dictated in bursts and starts: – I am the Lord your God. First… you shall have no other God than me… Gabriel was sweating, his tongue between his teeth. Hurry – the Good Lord said imperiously. 92 As soon as they had finished he had himself accompanied down to Moses to give him the Tablets. Gabriel was at his side, invisible, ruffled and worried. Do as I say – the Good Lord ordered Moses. His aspect was terrifying as he appeared in front of him. – Do it or else… He disappeared… He would never have wanted Moses to see him, his eyes full of tears, wounded, leaning on one of Gabriel’s wings. Excuse me, he whispered. Gabriel embraced him with his wings and led him up again. The Good Lord knew that from then on the more he felt fragile, alone and sad, the more he would have to show a terrible and fearful face. He had lost. He had had to bow down to the law of ‘either…or’. His fault? Where had he gone wrong with Lucifer? Or maybe he hadn’t gone wrong, and there was simply nothing to be done? However, the rebel son’s vengeance was beginning to become a reality and for him there was no other Good Lord. Or maybe there was one, but he wasn’t Good. 93 Achille e la tartaruga Finito il combattimento contro i Troiani, i guerrieri Greci si riposavano alla fresca ombra delle navi. Gli dei che erano dalla loro parte li proteggevano, e lungo i confini del campo le guardie vegliavano. Il mare era calmo, e spirava una dolce brezza. Gli eroi si sentivano al sicuro. Qualcuno, esausto, si era addormentato un po’ scompostamente, i pezzi della pesante armatura sparsi sui sassi intorno a lui. Ulisse e Achille erano vicini. Ulisse aveva lasciato ogni segno di guerra nella sua tenda. Indossava solo una tunichetta, e se ne stava sdraiato sui sassi a ginocchia piegate, le braccia dietro la testa, a guardare le nuvole. Achille, invece, non si sarebbe mai separato dalle sue armi. Lancia, scudo, elmo: aveva tutto addosso. Stava seduto in una posizione un po’ rigida, probabilmente tutt’altro che comoda. Certo che tu combatti proprio bene – osservò a un certo punto Ulisse, sollevandosi appena per lanciare un sasso in acqua e farlo rimbalzare. Oh, beh… – si schermì Achille, conscio della propria superiorità, ma non volendola farla pesare sull’amico. Però, se mi permetti – riprese questo – vorrei farti un’osservazione. Ma solo se non ti arrabbi. Figurati… dimmi pure. Con Ulisse, Achille, mostrava quasi sempre il meglio di sé, e raramente sfoderava la sua terribile Ira. Ecco… io penso che tu sia un po’ troppo pesante. Che manchi di agilità. Per l’armatura, dici? Lo sai che è necessaria. No, non lo dico solo per l’armatura. Ti ho osservato a lun95 go, ho guardato i tuoi movimenti. Sono micidiali ma lenti. Sei tu che manchi di agilità. Lento io? Il micidiale, l’invincibile Pelide Achille, il Piè-veloce… Hai promesso di non arrabbiarti. Non mi arrabbio, no, ma se dici delle assurdità… Non credo siano proprio assurdità. Ti ho detto che ci ho riflettuto – continuando a gettare sassi nell’acqua e a farli rimbalzare. – Penso che se facessi una corsa con un gatto, la perderesti. Per forza la perderei. Anche Zeus in persona perderebbe con un gatto (senza ricorrere ad artifici, si capisce). Il gatto è l’animale più agile e mobile che ci sia, salta, si arrampica, balza sugli alberi… e poi, perché mai dovrei mettermi in gara con un animale tanto nervoso e tanto piccolo? Beh, se vuoi saperlo, io penso che perderesti la gara anche con un animale molto meno nervoso e molto più piccolo. Sarebbe a dire? Sarebbe a dire una tartaruga. Ma fammi ridere! Va bene che sei l’Astuto Ulisse, ma come ti vengono certe idee, poi… E perché mai dovrei mettermi a competere con una povera piccola tartaruga, che per sua natura ci metterebbe un mese a camminare fra me e te? Non sarebbe leale, sarebbe indegno di un guerriero greco. E del Pelide Achille, poi, più indegno che mai. Sei proprio sicuro? – chiese Ulisse con quella sua aria astuta, mettendosi in bocca un’erbaccia spuntata fra i sassi. Cos’hai in mente, Astuto Ulisse? Oh, amico Achille, grande fra i guerrieri, non te la prendere se ti dico che tu non capiresti. Ho fatto una certa riflessione…una certa ipotesi… Ipotesi, riflessioni…! Non è che non capirei, è che non voglio capire. A volte voialtri intellettuali mi fate veramente arrabbiare. No, no, non preoccuparti: non sto per incenerirti con l’Ira di Achille. Però una lezione te la voglio dare. Sì, te la voglio proprio dare. E farò una corsa con una tartaruga proprio 96 qui, davanti a tutti, su questa spiaggia. Ehi, tu, ragazzo! – chiamò, rivolto a una guardia. Il giovane accorse. Dimmi, Divino Achille. Sono ai tuoi ordini. Cerca una tartaruga e portamela qui. Qui sulla spiaggia, Divino Achille? Che cosa ho detto? Sei sordo, forse? Vado, vado subito. Il ragazzo corse via come il vento. Dopo un po’, mentre fra i due amici era caduto il silenzio e Ulisse continuava a masticare il suo filo d’erba guardando pensoso le nuvole, la giovane guardia tornò. Mettila lì, dove il suolo è più liscio – ordinò Achille. E ora, Grande Achille? Osò chiedere il ragazzo. Ora vedrai una gara di corsa. Una gara? Fra il Piè-veloce e una tartaruga? Appunto. Lo so che non è leale, e che anzi è ridicolo, ma la farò per far contento il mio amico Ulisse. Il giovane ammutolì. Achille si alzò in piedi, con un fracasso di ferraglia. Intanto, gli altri guerrieri, incuriositi, si erano avvicinati ad assistere. Ulisse rimase a terra, col suo filo d’erba tra i denti. Sorrideva tra sé. I sofisti, e tra loro Zenone, erano di là da venire, ma Atena lo aveva illuminato. Lui sapeva già come sarebbe finita. Tra un punto A e un punto B c’è un punto intermedio C, pensò, continuando a masticare il filo d’erba. E tra un punto A e un punto C c’è un punto intermedio D, e tra un punto A e un punto D c’è un punto intermedio E, ancora, tra un punto A e un punto E c’è un punto intermedio F, e così via, fino alla paralisi completa del corridore… Sì, Ulisse sapeva già come sarebbe finita. La Tartaruga avrebbe vinto. Gli dispiaceva solo, un poco, per l’amico Achille. 97 Achilles and the tortoise After the battle against the Trojans, the Greek warriors were resting in the cool shade of the ships. The Gods who were on their side were protecting them, and the guards were keeping watch along the edge of the camp. The sea was calm, and there was a gentle breeze. The heroes felt safe. Some of them, exhausted, had fallen into a relaxed sleep, the pieces of their heavy armour scattered on the stones around them. Ulysses and Achilles were side by side. Ulysses had left all signs of war in his tent. He wore only a short tunic and was lying on the stones, his knees bent, his arms behind his head, gazing at the clouds. Achilles, instead, would never have parted from his weapons. His lance, his shield, his helmet: he wore them all. He was sitting rather rigidly, and probably quite uncomfortably. You certainly are an excellent fighter – Ulysses observed at one point, raising himself just enough to throw a stone over the water and watch it bounce. Oh, well… – Achilles answered modestly, conscious of his own superiority but not wishing it to weigh on his friend. However, if you’ll allow me – the former continued, I’d like to make one criticism. But only if you don’t get angry. Of course not… out with it. With Ulysses, Achilles almost always showed his best side and rarely unsheathed his terrible Anger. Well… I think you’re a little too heavy, you’re not very agile. Because of my armour…? You know it’s necessary. No, not only because of your armour. I’ve observed you at length, I’ve watched your movements. They’re deadly, but slow. It’s you who aren’t agile. 99 Me, slow? The deadly, invincible Achilles of Pelion, the Swift-Footed… You promised not to get angry. No, I’m not angry, but if you talk nonsense… I don’t really think it’s nonsense. I told you I thought about it as I threw stones into the water. I think that if you ran a race with a cat you’d lose. Naturally I’d lose. Zeus himself would lose against a cat (unless, of course, he resorted to cunning). Cats are the most agile and mobile of animals, they jump, they climb, they leap into trees… And anyhow why should I compete with such a small, nervous animal? Well, If you want to know, I think you’d lose a race even with a much smaller and far less nervous animal. You mean? I mean a tortoise. Are you joking! It’s true that you’re the Cunning Ulysses, but wherever do you get these ideas?… And whyever should I start competing with a poor little tortoise who because of its very nature would take a month to walk between you and me? It would be disloyal, it would be unworthy of a Greek warrior. And more unworthy than ever of Achilles of Pelion. Are you quite sure? – Ulysses asked, glancing at him shrewdly as he chewed on the weed he had found between the stones. What’s on your mind Cunning Ulysses? Oh, my friend Achilles, great among warriors, take it easy if I tell you that you wouldn’t understand. I’ve reflected… I have a hypothesis… Hypotheses, reflections…! It’s not that I wouldn’t understand, it’s that I don’t want to understand. At times you intellectuals drive me crazy. No, no, don’t worry: I’m not about to incinerate you with Achille’s Anger. But I want to teach you a lesson. Yes, that’s what I want to do. And I’ll run a race with a tortoise right here, in front of everyone, on this beach. Hey, you, boy! He called, addressing one of the guards. 100 The young man rushed up. Tell me, Divine Achilles, I’m at your orders. Look for a tortoise and bring it to me here. Here on the beach, Divine Achilles? What did I say? Are you deaf? I’ll go, I’ll go right now. The boy ran like the wind. After a while, as silence fell between the two friends and Ulysses continued chewing on his blade of grass, looking pensively at the clouds, the young guard returned. Put it there, where the ground is smoother – Achilles ordered. And now, Great Achilles? The boy dared to ask. Now you’ll see a race. A race? Between Swift-Foot and a tortoise? Precisely. I know it’s disloyal, and even ridiculous, but I’ll run it to please my friend Ulysses. The young man was silent. Achilles stood up with a clatter of metal. In the meantime, their curiosity aroused, the other warriors had drawn closer to assist at the scene. Ulysses remained sitting on the ground, his blade of grass between his teeth. He was smiling to himself. The sophists, and among them Zeno, were still to come, but Athena had enlightened him. He already knew how it would end. Between a point A and a point B there’s an intermediate point C, he thought, continuing to chew on his blade of grass. And between a point A and a point C there’s an intermediate point D, and between a point A and a point D there’s an intermediate point E, and, again, between a point A and a point E there’s an intermediate point F, and so forth, until the runner’s complete paralysis. Yes, Ulysses already knew how it would end. The Tortoise would win. Only he was sorry – just a little sorry – for his friend Achilles. 101 Il lupo e l’agnello: la vera storia Vorrei raccontarvi la vera storia del lupo e dell’agnello. Lo so che molti di voi la conoscono. Ma la verità è che la sanno per sentito dire. A loro l’ha raccontata la nonna, che a sua volta l’aveva ascoltata dalla sua nonna, e questa dalla propria, e così via fino alla più antica trisnonna. Si capisce che, a furia di raccontarla, la storia è cambiata un po’. Anche perché tutti, per tanti secoli, hanno avuto talmente paura del lupo, che erano incapaci di pensare che potesse non vincere. Io però ho avuto la fortuna di conoscere uno scoiattolo che ha assistito alla scena e mi ha raccontato come sono veramente andate le cose. Se ne stava nascosto in cima a un albero di noci, che si trovava in alto, proprio accanto alla montagnola di sassi da cui sgorgava il torrente. E dunque vicino, vicinissimo al lupo. Infatti aveva una paura birbona: cercava di stare immobile tra le foglie, ma tremava tutto. Il lupo, però non si accorse di lui. Era assetato, e bevendo, guardava l’acqua che ingurgitava a grandi linguate. Ora, pensava, ci sarebbe voluta una buona colazione. Ed ecco, appena ebbe bevuto a sazietà, allargando appena lo sguardo, vide l’agnellino sotto di lui. Spiccava, bianco e tenero, fra i sassi e l’erba. Gli venne l’acquolina in bocca e improvvisamente una fame violenta si impossessò di lui. Voleva nel suo stomaco quel batuffolo di carne giovanissima. Lo voleva subito. Subito, capito? Gli spettava di diritto, perché lui era Il Lupo ed era forte, e l’agnello era L’Agnello, ed era debole. Più semplice di così… Lo scoiattolo, benché preoccupato per l’agnello, adesso era tranquillo per sé: era chiaro che per nulla al mondo, in quel momento, il lupo avrebbe guardato in alto. Non lo avrebbe vi103 sto. No, fissava l’agnello. E subito, prepotente, gli rivolse le parole che tutti conosciamo: Perché, gli disse, hai intorbidato l’acqua che io bevo? L’agnello, che era molto piccolo e mal si reggeva sulle zampe, non sapeva ancora veramente parlare e nemmeno capiva bene. Tuttavia capì che il lupo lo minacciava, e si mise a belare. Voleva la sua mamma, che lo proteggesse da quegli occhi cattivi, rossi infiammati e ingordi. Belò ancora, disperato. Ed ecco – e qui è importante la testimonianza dello scoiattolo – di colpo, come d’incanto, alle sue spalle si materializzò il cane custode del gregge. Era grande come il lupo, e gli somigliava anche un po’, ma aveva tutt’altro sguardo, e l’agnello capì che stava dalla sua parte. Si rifugiò fra le sue zampe. Il cane scodinzolò. Poi, con una voce robusta quanto quella del lupo, che pure all’agnello suonava protettiva, disse, con disprezzo: Vigliacco, forte coi deboli e debole coi forti. Pensi che il mondo girerà così in eterno, eh? Ti sbagli di grosso, e prima o poi ti darò la lezione che ti meriti. Ora non posso, ho da fare. Devo riportare a casa questo bamboccio girovago e birbante. E diede all’agnello una robusta leccata, che lo fece rotolare nell’erba. L’agnello belò ancora, ma senza paura, anzi con gioia. Gli pareva un gioco. Purtroppo non so dirvi cosa fece il lupo a quel punto. Lo scoiattolo, infatti, di nuovo preoccupato per sé a causa della inaspettata piega degli avvenimenti, piano piano era scivolato giù dall’albero, e se l’era data a gambe per il prato fino a raggiungere il prossimo albero di noci. Una cosa è certa: il lupo non lo mangiò, altrimenti non avrebbe potuto raccontarmi la storia. 104 The wolf and the lamb: the true story I would like to tell you the true story of the wolf and the lamb. I know that many of you know it. But the truth is that people know it from hearsay. Their grandmothers told it to them, and they heard it from theirs, and so on and so forth from grandmother to grandmother. So it’s easy to understand that by dint of telling it the story has undergone some changes. Also because everyone, for many centuries, has been so afraid of wolves that they simply couldn’t believe that they might not win. I, however, have been lucky enough to know a squirrel who witnessed the scene and told me how things really went. He was hiding in the top of a nut tree which stood high up, right next to the hillock of stones out of which the stream springs. And so he was close, very close to the wolf. In fact he was devilishly afraid: he tried to keep very still among the leaves, but he was trembling all over. However the wolf didn’t notice him. He was thirsty and while he drank he looked at the water he was greedily gulping down. Now, he thought, I’d need a good breakfast. Well, just as he had drunk his fill and was looking around he saw the lamb down beneath him. The lamb stood out clearly, tender and white, among the stones and grass. The wolf’s mouth watered and suddenly he was seized with violent hunger. He wanted that fluffy, very young flesh in his stomach. He wanted it right away. Right away, do you understand? It was his by rights because he was the Wolf and was strong, and the lamb was the Lamb, and was weak. Nothing simpler… Though the squirrel worried for the lamb he no longer worried for himself: it was obvious that at that moment nothing in 106 the world would have made the wolf look up. He wouldn’t see him. No, the wolf’s eyes were fixed on the lamb. And in a bullying voice he spoke the words that we all know: Why, he said, have you muddied the water I drink? The lamb, who was very small and could barely stand on his legs, hadn’t yet really learnt how to speak nor could he understand very well. But he did understand that the wolf was threatening him; and he started to bleat. He wanted his mother, to protect him from those wicked, red, inflamed, greedy eyes. He bleated again, in despair. And at that moment – and this is where the squirrel’s testimony is important – as if by magic, the dog in charge of protecting the flock appeared behind him. He was as big as the wolf, and even looked rather like him, but his gaze was quite different and the lamb understood that he was on his side and took refuge between his paws. And the dog wagged his tail. Then, in a voice as robust as the wolf’s – a voice which sounded protective to the lamb – he said scornfully: Coward, you’re strong with the weak and weak with the strong. Do you think the world will spin like that forever? Well, you’re quite mistaken and sooner or later I’ll teach you the lesson you deserve. I can’t now, I’m busy. I must take this wandering little rascal home. And he licked the lamb so energetically that he made him roll over in the grass. The lamb bleated again, but this time without fear – in fact joyfully. It seemed like a game to him. Unfortunately I can’t tell you what the wolf did at that point. For the squirrel, who was worried again for himself because of the unexpected turn things had taken, had quietly slipped down the tree and was running through the grass to the next nut tree. One thing is certain: the wolf didn’t eat him, otherwise he couldn’t have told me the story. 107 Laura Lilli vive a Roma dove è nata nel 1937. Scrittrice e giornalista letteraria, ha fatto parte della redazione Cultura de «la Repubblica» fin dalla fondazione (1976). Autrice di saggi, di narrativa e di poesia, ha pubblicato sette libri. Fra questi il romanzo sperimentale Zeta o le zie (Bompiani, Milano 1980), i racconti capresi La Coccodrilla, tradotto in inglese nel 2005 (La Conchiglia, Capri 1993 e 2005) e i poemetti in italiano e in inglese Sweet to Ants/Dolce per le formiche, Otto Quarti d’ora/Catchlines e Il buon dio e la tartaruga/The good god and the turtle tutti pubblicati da Empirìa (Roma) rispettivamente nel 1996, nel 2001 e nel 2007. Laura Lilli lives in Rome where she was born in 1937. A writer and literary journalist, she has been a member of the cultural department of the daily paper «la Repubblica» since 1976, when it was founded. She has written essays, fiction and poems, and has published seven books. Among them, the “avantgarde” novel Zeta o le zie (Bompiani, Milano 1980), the Capri stories The She-Crocodile (translated into English in 2005, Capri, la Conchiglia) and two collections of poems in Italian and English: Sweet to Ants/Dolce per le formiche (Empirìa, Roma,1996), Catchlines/Otto quarti d’ora (Empirìa, Roma 2001) and Il buon dio e la tartaruga/The good god and the turtle (Empirìa, Roma 2007). Elisa Montessori, nata a Genova, vive e lavora a Roma. Nel 2006 personale alla Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna di Roma con «Shanghai blues» e nel 2007 «Libri ibridi» alla Galleria Angelica di Roma. Ha partecipato nel 2009 alla Biennale di Venezia con un «Omaggio a Simone Weil». Elisa Montessori was born in Genoa and lives and works in Rome. In 2006 she had a personal exhibition at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Rome with “Shanghai Blues” and in 2007 “Hybrid Books” at the Galleria Angelica of Rome. In 2009 she took part in the Venice “Biennale” with a “Homage to Simone Weil”. 108 Indice / Index 7 12 Chilometro The story of a mile-long line of verse 19 Piscine 21 Swimming pools 25 Le due eternità 31 The two eternities 39 Africa 42 Africa 47 Congresso 51 Congress 57 Comunione 60 Communion 65 Football 72 Football 81 Aut… aut 88 Either… or! 109 95 Achille e la tartaruga 99 Achille and the tortoise 103 Il lupo e l’agnello: la vera storia 106 The wolf and the lamb: the true story 108 Nota / Note 110 Finito di stampare nel febbraio 2010 dalla E.S.S. Editorial Service System srl Roma