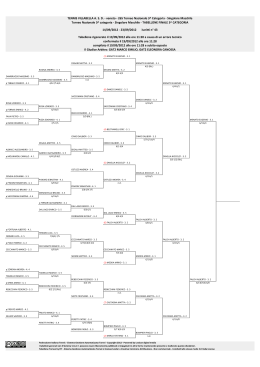

CDS 295/1-2 DDD DIGITAL LIVE RECORDING ^ BEDRICH SMETANA (Litomyšl, 1824 - Prague, 1884) DALIBOR Libretto by Josef Wenzig CHARACTERS AND INTERPRETERS Dalibor (tenor) Milada (soprano) Wladislaw (baritone) Jitka (soprano) Beneš (bass) Budivoj (baritone) Vítek (tenor) First judge (bass baritone) Second judge (bass) Third judge (bass baritone) Valerij Popov Eva Urbanova Valeri Alexejev Dagmar Schellenberger Jiri Kalendovsky Damir Basyrov Valentin Prolat Carmine Monaco Alexandr Blagodarnyi Bruno Pestarino ORCHESTRA E CORO DEL TEATRO LIRICO DI CAGLIARI Chorus master: Paolo Vero Conductor: Yoram David Eva Urbanova Valerij Popov 2 12345678910 11 12 - CD 1 Act One Dnes ortel bude provolán (Chorus) Opuštìného sirotka malého (Jitka) Orchestral Již víte, jak to krásné království (Wladislaw) Již uchopte se slova (Wladislaw) Pohasnul den a v hradì (Milada) Jaký to zjev! (Milada) Zapírat nechci, nejsemt zvyklý lháti (Dalibor) Zloèinem tak pomáhals sobì sám (Wladislaw) Tak, Dalibore (a Judge) U svých mne zde vidíte nohou! (Milada) Jaká to bouøe òadra mi plní (Milada) 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 - Act Two Ba nejeveselejší je tento svìt (Mercenaries) Dle této písnì poznávám je vždy (Jitka) Je Daliborùv osud tobì znám ? (Jitka) Ba nejveselejší je tento svìt (Mercenaries) Nejvìtší bedlivosti tøeba (Budivoj) Ach, jak tìžký žalárníka (Budivoj) Hotovo všecno (Milada) Jak je mi? (Milada) Zde jsou ty housle (Beneš) 03’38” 02’41” 02’16” 07’01” 03’04” 02’20” 04’04” 02’40” 04’41” CD 2 1 - Orchestral 2 - Nebyl to on zas? (Dalibor) 3 - Vem tento chudý dárek z ruky mé (Milada) 58’41” 02’43” 02’44” 11’04” 45678910 11 12 13 - Act Three Pøeslavný kríali, pánové pøejasní (Budivoj) Ètyøicet let již tomu bude (Beneš) V tak pozdní dobu povolal jsem vás sem (Wladislaw) Jste již u konce? (Wladislaw) Tot tøetí noc, kterou mi naznaèila (Dalibor) Ó nebe! Bez okovù? (Budivoj) March Nezaslechli jste ještì houslí zvuky? (Milada) Milado! (Dalibor) Nepøátel zástup poražen a zbit (Budivoj) 73’33” 02’49” 04’20” 02’11” 03’25” 03’08” 06’16” 01’22” 05’29” 02’47” 04’41” 03’25” 03’36” 03’15” 03’22” 04’55” 04’58” 03’09” 06’36” 01’47” 04’55” 06’22” 02’54” Smetana al tracollo; infatti, dopo un inizio stentato, quella fu l’unica, tra le sue opere, ad entrare nel repertorio dei teatri; soltanto la commedia brillante Il bacio sfiorò, in alcuni momenti, la sua popolarità. La prima opera seria di Smetana, I brandeburghesi in Boemia, ebbe un grande successo nel primo anno (1866) con quattordici repliche, ma in seguito queste divennero sempre meno frequenti e rarissime le nuove produzioni. Un colpo particolarmente duro, appena cinque mesi dopo le celebrazioni per La Sposa venduta, venne dall’accoglienza data alla sua ultima opera Il muro del diavolo: la produzione, realizzata con povertà di mezzi ed idee, sembrò tremendamente logora, soprattutto se rapportata allo straordinario successo dell’opera Dimitrij di Dvorák rappresentata nello stesso mese. Il destino di Dalibor, in particolare, fu motivo di seria sofferenza. Smetana era particolarmente affezionato a questo lavoro. La librettista delle sue ultime opere, Eliska Krasnohorská, ne parlava considerandola “perla dell’opera romantica ceca”. Smetana volle far conoscere l’opera al suo idolo musicale Franz Liszt, il quale, dopo aver sentito e sinceramente apprezzato Dalibor suonata dall’autore al pianoforte, in contrasto con i più severi critici di Praga non la considerò affatto wagneriana. Quando Miezyslav Kaminsky, tenore polacco in rapida ascesa, dotato di grande talento musicale e istinto scenico, venne assunto al Teatro Provvisorio di Praga, Smetana sperò che accettasse di interpretare il ruolo di Dalibor per dimostrare finalmente la “sincerità dell’opera”. Sfortunatamente l’opera non venne mai rappresentata durante la permanenza a Praga del tenore. La triste verità è che Dalibor, assieme alle altre opere serie I brandeburghesi e Libuše, non catturò mai l’immaginazione del pubblico quanto le sue due commedie La sposa venduta e Il bacio. La reazione di un gruppo di critici fu sicuramente tra i DALIBOR Un inno alla musica e si considera Smetana padre di un risveglio nazionale ceco, è davvero sorprendente quanto poco siano conosciute al grande pubblico le otto opere del compositore. È però vero che la storia, inesorabile e spietata, ha sempre determinato la fortuna dell’opera lirica. Ad esempio, a parte i contemporanei dell’epoca di Smetana, ben poca attenzione è stata data ad importanti autori dell’opera ceca, quali Karel Sebor, Karel Bendl e Vilem Blodek, che operarono nel periodo tra il 1860 e il 1880. Smetana stesso, anche negli anni di maggior successo, fu vittima della natura discriminatoria del gusto. Le sue stesse reazioni alle celebrazioni in onore della centesima rappresentazione della Sposa venduta, avvenuta il 5 maggio 1882, sono illuminanti. Sebbene fosse commosso dall’affetto del pubblico e dal consistente premio in denaro e titoli, Smetana apparve ambiguo nel definire La sposa venduta “poco più di un giocattolo”, un’opera scritta quasi per fare dispetto ai detrattori che lo accusavano di essere incapace di comporre in uno stile semplice; Smetana anzi andò oltre, affermando che quanti lodavano con tanto trasporto La sposa venduta, di fatto offendevano tutti gli altri suoi lavori, ed in particolare Dalibor, opera della quale era sicuramente più orgoglioso. Si può credere che vi fu una relazione tra le celebrazioni per La sposa venduta e le ansie che da queste scaturirono, provocando in lui notevoli problemi di salute, certamente aggravati dalla crescente paranoia per i successi sempre più evidenti di Dvoøák. Paradossalmente si può affermare che la fortuna della Sposa venduta, che per lo straordinario successo metteva inevitabilmente in ombra le altre sue opere, portò S 4 motivi che determinarono questo fatto. Il panorama culturale di Praga, in particolare quello musicale, era lacerato da numerosi contrasti: tra questi, di grande rilevanza, era la questione sull’influenza esercitata da Wagner. Per quanto Smetana ammirasse l’opera di Wagner, non fu certamente un imitatore pedissequo, anzi fu ben conscio dei pericoli nascosti nella possibilità di utilizzare modelli wagneriani proprio nei giorni in cui si gettavano le basi di uno stile peculiare dell’opera ceca. Questa consapevolezza non allontanò comunque da Dalibor l’accusa, da parte di una nutrita schiera di critici, di essere stata concepita in uno stile wagneriano: la trama, in parte tratta dal mito, e l’uso di un sistema di metamorfosi tematiche, non lontane dai leitmotiv, poterono essere pretestuosamente utilizzati a sostegno di quell’accusa; in quel caso Dalibor sarebbe apparso veramente il tentativo di superare Tristan und Isolde. Oggi queste affermazioni appaiono davvero insignificanti, ma in quei giorni ebbero un impatto significativo sul pubblico. Smetana aveva una sua chiara idea sui motivi dello scarso successo di pubblico di Dalibor: “Solo adesso capisco quanto poco raffinato, educato alla musica, sia il nostro pubblico, malgrado la straordinaria offerta di una città come Praga con istituzioni musicali, le tante società di concerti, le opere, i teatri in abbondanza...”. Sicuramente caustico, ma con un fondo di verità. Il pubblico di Praga aveva una grande passione per il divertissement, per le arie in rima su motivi popolari e per i cori reboanti. Tutti questi elementi si ritrovavano in abbondanza nei Barndeburghesi e nella Sposa venduta. In Dalibor, con una materia ben più alta e la delicata sensibilità del protagonista, Smetana aveva evitato con accuratezza di toccare quelle corde. Sicuramente la gran parte del pubblico non riuscì però a comprendere quanto veniva offerto. Dalibor è certamente la più straordinaria pagina d’opera di Smetana e rappresenta un lavoro assai più raffinato dei primi due per il teatro. Sin dal principio Smetana entra direttamente nel vivo della storia; infatti il tessuto musicale si sviluppa con grandissima maestria, evitando di utilizzare una ouverture quale facile strumento per catturare l’attenzione del pubblico. La scala ascendente e cupa che emerge sin dalle prime battute è il sostrato musicale capace di suggerire la gran parte dei motivi tematici, di dare unità all’intera struttura e di porsi quale punto focale dell’opera. L’impressionante capacità di variazione può essere evidenziata dalla varietà nello sviluppo di questo tema: nella versione originale fa riferimento certamente all’angoscia del protagonista Dalibor, in seguito, modulato in una fanfara brillante in sol maggiore, diventa elemento melodico per il richiamo di Jitka a salvare il suo eroe. Una successiva modulazione nel primo atto getta un’ombra sulla confessione d’amore di Dalibor per Zdenì k e sulla giustificazione per l’atto di vendetta dopo l’assassinio dell’amico. Sebbene si tratti di una confessione intima, la bellezza poetica del suo canto trasforma i propositi di vendetta di Milada nel desiderio di liberare Dalibor. Per inciso, appare interessante il fatto che la melodia che emerge nel canto di Dalibor, sull’inutilità di una vita senza Zdenì k, ha dato a Smetana il tema per la gloria e caduta della nazione ceca in Vyséhrad, il primo dei poemi sinfonici di Ma vlast. Il lirismo diventa ancora più alto ed intenso nel duetto d’amore tra Dalibor e Milada, forse il più raffinato tra quelli composti da Smetana, alla fine del secondo atto. La qualità dell’invenzione in tutta l’opera è straordinaria: in Dalibor lo stile melodico di Smetana si innalza ancor più che nella Sposa venduta, la sua voce più intima è qui ancora più presente e l’originalità della sua retorica pervade tutta l’opera, il disegno musicale all’unisono che appare improvvisamente all’inizio del secondo atto, ad esempio, potrebbe essere stato composto da Janáèek. E certamente non si possono trascurare altri 5 momenti ed aspetti di straordinario interesse, come il coro dei mercenari all’inizio del secondo atto; Smetana sembra poi prendersi gioco della tronfia vanità del potere, accompagnando l’ingresso dei giudici nel primo atto con una marcia, di fatto zoppa, cadenzata in tre tempi. Ci sono alcune questioni legate sia alla trama che allo sviluppo drammatico in Dalibor: la semplice dinamica dell’amore nato dall’incontro di Milada con Dalibor, è complicata dalla presenza, seppure solo da morto, di Zdenì k nella vicenda. Chiaramente, per il pubblico che per la prima volta assistette all’opera, la scena d’apertura era lenta e, per il pubblico di sempre, il finale arriva fin troppo d’improvviso. A parte ogni altra considerazione, il fatto davvero importante è la bellezza della partitura; l’opera è insieme una celebrazione della musica e, attraverso i suoi simboli, Zdenì k e il suo violino, un inno alla nazione ceca. Se è vero che a molti tra i contemporanei di Smetana sfuggì la complessità e la bellezza dell’opera, certamente così non fu per Antonín Dvoøák. Violista nell’orchestra della prima di Dalibor, Dvoøák seppe raccogliere l’insegnamento di questa straordinaria partitura, che influì per molti versi nelle sue composizioni per la scena. Jan Smaczny Professore di musica all’Università di Belfast (Traduzione dall’inglese di Giancarlo Liuzzi) 6 only one of his operas that did. Smetana’s first serious opera, The Brandenburgers in Bohemia, did extremely well in its first year (1866) with fourteen performances, but after this outings were infrequent and new productions rarities. A particularly bitter blow, coming just five months after the hundredth performance of The Bartered Bride, was the reception of his last opera The Devil’s Wall: poorly and ignorantly produced, it looked decidedly threadbare beside the magnificent success of Dvoøák’s grand opera, Dimitrij, staged in the same month. The fate of Dalibor, in particular, was a consistent source of grievance. He was particularly attached to the work. The librettist of three of his later operas, Eliska Krásnohorská, referred to it as the “pearl of Romantic Czech opera”. Smetana took pains to show it to his musical idol, Franz Liszt, who after hearing the work played by the composer at the piano, thoroughly approved of it and, contrary to the views of the more virulent of Prague’s critics, did not find it Wagnerian at all. When a new tenor, the Pole Mieczyslav Kaminsky, possessed of great vocal talent and genuine acting ability, was appointed to the Prague Provisional Theatre, Smetana hoped he would take on the role of Dalibor in order to demonstrate, in his own words, “the truthfulness of the opera” (unfortunately there was no staging of Dalibor during his time there). The sad fact was that Dalibor (along with his other serious operas The Brandenburgers and Libuše) never really captured audiences imaginations in the manner of his two comedies, The Bartered Bride and The Kiss. Among the possible reasons for this was the reaction of certain critics. The musical landscape of Prague was riven by numerous fault-lines, a major one of which was the whole question of Wagnerian influence. While Smetana certainly admired Wagner’s music, he was no slavish imitator; indeed, he was well aware of the dangers of adopting the Wagnerian model in the early days of establishing a DALIBOR A hymn to music iven Smetana’s status as the musical founding father of the Czech national revival, it is perhaps surprising that we do not hear more of his eight operas. But history has a devastatingly unsentimental way of dealing with the operatic repertoire. Posterity has hardly been kind to other luminaries of Czech opera in the 1860s and 1870s, such as Karel Sebor, Karel Bendl and Vilém Blodek, and Smetana, even in his own day, was a victim of the discriminatory nature of taste. His own reactions to the celebrations of the hundredth performance of The Bartered Bride, on 5 May 1882, are instructive. Although touched by the warmth of the audience and the magnificent presentation (including a savings book and money bonds in a considerable amount), Smetana appeared to be ambivalent about the work referring to it as little more than a “toy”, a work written to spite those who said he could not write anything in a light style; he even went on to suggest that those who praised The Bartered Bride so excessively were insulting his other operas. Servác Heller tells a similar story: “Smetana was not that enthusiastic about The Bartered Bride. He took much more pride in other of his operas, especially Dalibor, and he objected when The Bartered Bride was praised greatly in his presence ...”. To an extent, Smetana’s reactions to the hundredth performance celebrations of The Bartered Bride can be put down to his own failing health and anxieties, including considerable paranoia about Dvoøák’s rising fortunes. But the way in which The Bartered Bride had eclipsed his other operas must have rankled; after a slightly shaky start, it was the only one of his operas performed consistently during his lifetime; the charming comedy, The Kiss, at times approached its popularity, but it was the G 7 Czech operatic style. This did not, however, prevent a vigorous claque from denouncing Dalibor as Wagnerian: its quasi-mythical story, the use of a system of thematic metamorphosis not unlike leitmotif all could be drawn into the accusation of Wagnerism; Dalibor, it seems, was an attempt to “outdo” Tristan. Today this idiotic flapdoodle seems hardly worth considering, but it had an impact on the public. Smetana had his own analysis of the public’s lack of response to Dalibor: “... I now recognise how little educated - musically educated our public is, despite all the musical establishments, concerts, operas, theatres which a city like Prague has in abundance ... ”. This is a little harsh, but there is an element of truth. Prague audiences had an enormous fondness for divertissement, for the popular tone in strophic arias and rabble-rousing choruses. All these elements existed in abundance in The Brandenburgers and The Bartered Bride; Dalibor, with its elevated tone and the delicate sensibility of its hero conspicuously avoided striking any of these chords. The great pity for the audience is that many did not recognise what they missed. Dalibor is Smetana’s loveliest operatic score and a great deal subtler than his first two works for the stage. From the very start, the musical fabric unfolds with enormous skill; eschewing an attention-grabbing overture, Smetana pitches straight into the drama. The brooding rising scale figure which soon emerges is the musical fibre for much of the melodic writing in the opera, uniting the whole structure and providing a striking symbolic touchstone. The impressive nature of Smetana’s powers of transformation can be gauged by the development of this theme: in its original version, the theme clearly relates to Dalibor’s predicament, later it provides the motivic background, transformed into a bright G major fanfare, for Jitka’s call to free her hero. A further metamorphosis later in act one shadows Dalibor’s account of his love for Zdenì k and the justification for his act of revenge after he was killed. Apart from being a personal confession, its sheer lyrical beauty also turns Milada from thoughts of revenge to a desire to free Dalibor. (Interestingly, the melody that emerges as Dalibor sings of the meaningless of life without Zdenì k, provided him with the theme for the glory and fall of the Czech nation in Vysì hrad, the first of the symphonic poems of Má vlast.). The lyricism becomes still more intense in the love duet, perhaps Smetana’s finest, between Dalibor and Milada at the end of the second act. The quality of invention throughout the opera is extraordinary: in Dalibor, Smetana’s melodic style crystallises to an even greater extent than in The Bartered Bride; his personal voice is heard much more strongly and the originality of his rhetoric is apparent everywhere - the striking unison figure at the start of the second act could almost be by Janáèek. Nor is the work without some lighter aspects, notably in the chorus of mercenaries at the start of act two; Smetana also seems to be poking fun at fustian authority in the entry of the judges in the first act, wrong-footing them by providing a march in three-four time. There are problems with plot and dramaturgy in Dalibor: the simple dynamics of boy meets girl and then they fall in love are complicated by the fact that there is another boy in the way, even if he is dead. Clearly, for its original public, the stately development of the opening scene was a little too slow, and for audiences ever since the premiere, the end of the opera does come very abruptly. But the real point of this remarkable score is its beauty; the work is as much a celebration of music with Zdenì k and the violin as symbols of the nation. For many of the audience this lesson was not obvious enough; luckily the message was not lost on one listener. Antonín Dvoøák, who played at its premiere. If any score proved an influence on his own developing style 8 then it is Dalibor - in many ways the promise of this marvellous work is fulfilled in Dvoøák’s own music for the stage. DALIBOR Eine Hymne an die Musik Jan Smaczny Professor of Music at the University of Belfast ird Smetana als Vater eines nationalen tschechischen Erwachens angesehen, so ist es wirklich überraschend, wie wenig die acht Opern des Komponisten dem Publikum bekannt sind. Es stimmt aber, daß die unerbittliche, unbarmherzige Geschichte immer über den Erfolg einer Oper bestimmt hat. Abgesehen von Smetanas Zeitgenossen wurde beispielsweise bedeutenden Komponisten der tschechischen Ära wie Karel Sebor, Karel Bendl und Vilem Blodek, die zwischen 1860 und 1880 tätig waren, recht wenig Aufmerksamkeit geschenkt. Smetana selbst war auch in seinen erfolgreichsten Jahren ein Opfer des diskriminierenden Geschmacks. Erhellend sind dazu seine Reaktionen auf die Feiern zu der am 5. Mai 1882 erfolgten hundertsten Vorstellung der Verkauften Braut. Obwohl Smetana von der Zuneigung des Publikums und der beträchtlichen Auszeichnung mit Geld und Titeln gerührt war, erschien seine Definition der Verkauften Braut als “wenig mehr als ein Spielzeug”, als Oper, die fast deshalb geschrieben wurde, um seinen Verleumdern entgegenzutreten, die ihm Unfähigkeit vorwarfen, eine Oper in einfachem Stil zu schreiben, zweideutig. Smetana behauptete sogar, daß jene, welche Die verkaufte Braut so leidenschaftlich lobten, effektiv alle seine anderen Werke beleidigten, und speziell Dalibor, die Oper, auf welche er sicherlich am stolzesten war. Wir können annehmen, daß zwischen den Feiern für Die verkaufte Braut und den Ängsten, welche sie bewirkten und dem Komponisten beträchtliche gesundheitliche Probleme einbrachten, ein Zusam-menhang besteht. Diese Probleme wurden sicherlich noch durch den wachsenden Verfolgungswahn gegenüber den W 9 immer deutlicheren Erfolgen Dvoráks verschärft. Paradoxerweise kann gesagt werden, daß der Erfolg der Verkauften Braut, der in seiner Außerordentlichkeit Smetanas andere Werke unvermeidlicherweise in den Schatten stellte, den Komponisten zum Zusammenbruch führte, war sie doch nach mühsamem Beginn die einzige seiner Opern, die in das Repertoire der Opernhäuser Eingang gefunden hatte. Nur die komische Oper Der Kuß vermochte eine Zeitlang ihre Popularität zu erreichen. Die Brandenburger in Böhmen, Smetanas erste ernste Oper, war im Uraufführungsjahr (1866) mit vierzehn Vorstellungen sehr erfolgreich, doch wurden diese dann immer weniger häufig und die Neuins-zenierungen ganz selten. Kaum fünf Monate nach den Feierlichkeiten für Die verkaufte Braut war es ein harter Schlag für Smetana, wie seine jüngste Oper Die Teufelswand aufgenommen wurde. Die an Mitteln und Einfällen ärmliche Produktion schien schrecklich abgenutzt, vor allem im Vergleich zum außerordentlichen Erfolg von Dvoøáks im gleichen Monat aufgeführten Dimitrij. Im besonderen war das Schicksal von Dalibor ein Grund für ernstes Leid. Smetana war dieser Oper besonders zugetan. Eliska Krasnohorská, die Librettistin seiner letzten Werke, sprach über sie als “Perle der romantischen tschechischen Oper”. Der Komponist spielte sie seinem Idol Franz Liszt auf dem Klavier vor, der Dalibor aufrichtig schätzte und das Werk im Gegensatz zu den gestrengen Prager Kritikern überhaupt nicht als von Wagner beeinflußt betrachtete. Als der soeben Karriere machende polnische Tenor Miezyslav Kaminsky, der hohes musikalisches Talent mit sicherem szenischen Instinkt verband, an das Prager Provisorische Theater engagiert wurde, hoffte Smetana, er würde den Dalibor singen, um endlich die “Aufrichtigkeit der Oper” zu beweisen. Leider wurde das Werk während der Prager Zeit des Tenors nie gegeben. Die traurige Wahrheit ist, daß Dalibor - zusammen mit den anderen ernsten Opern Die Brandenburger und Libussa - die Vorstellungskraft des Publikums nie so für sich einnahm wie die beiden heiteren Werke Die verkaufte Braut und Der Kuß. Die Reaktion eines Gruppe von Kritikern gehörte sicherlich zu den diese Tatsache bewirkenden Gründen. Das kulturelle (und speziell das musikalische) Panorama Prags war von zahlreichen Kontrasten zerrissen. Unter diesen war die Frage des von Wagner ausgeübten Einflusses von großer Bedeutung. Obwohl Smetana Wagners Werk bewunderte, war er sicherlich kein sklavischer Nachahmer, sondern sich im Gegenteil über die verborgenen Gefahren einer Verwendung Wagner’scher Vorbilder gerade in den Tagen im klaren, in welchen die Grundlagen für einen eigenen Stil der tschechischen Oper gelegt wurden. Dieses Bewußtsein hielt aber von Dalibor seitens einer umfangreichen Kritiker-gruppe die Anklage nicht fern, im Stile Wagners entstanden zu sein. Die teilweise dem Mythos entnommene Handlung und die Verwendung von mit den Leitmotiven verwandten Themenmetamorphosen dienten als Vorwand zur Stützung dieses Vorwurfs, denn in diesem Falle hätte sich Dalibor wirklich als Versuch einer Überwindung von Tristan und Isolde erwiesen. Diese Behauptungen erscheinen heute wirklich bedeutungslos, hatten damals aber eine starke Wirkung auf das Publikum. Smetana hatte eine sehr klare Vorstellung über die Gründe des geringen Publikumserfolgs von Dalibor: “Erst jetzt sehe ich, wie wenig raffiniert und zum Musikhören unser Publikum erzogen ist, trotz des außerordentlichen Angebots einer Stadt wie Prag mit ihren Musikvereinen, vielen Konzertvereinigungen, Opernhäusern und zahlreichen Theatern...”. Sicher ätzend, aber mit einem Körnchen Wahrheit. 10 Prags Publikum hatte eine starke Vorliebe für das Divertissement, für gereimte Arien auf volkstümliche Melodien und für bombastische Chöre. Alle diese Elemente finden sich in Hülle und Fülle in den Brandenburgern und in der Verkauften Braut. Bei Dalibor hatte Smetana angesichts einer sehr viel höherstehenden Thematik und der heiklen Empfind-lichkeit des Titelrollenträgers sorgfältig vermieden, derartige Saiten anzuschlagen. Dem Großteil des Publikums gelang es aber sicherlich nicht, das Angebotene zu verstehen. Dalibor ist mit Sicherheits Smetanas außergewöhnlichste Oper und stellt ein sehr viel raffinierteres Bühnenwerk als die beiden vorhergehenden dar. Der Komponist geht von Anfang an direkt in medias res. Das musikalische Gewebe entwickelt sich mit größter Meisterschaft und vermeidet den Einsatz einer Ouvertüre als leichtes Mittel, das Interesse des Publikums gefangenzunehmen. Die aufsteigende, düstere Skala, die bereits aus den ersten Takten klingt, ist die musikalische Grundlage, welche den Großteil der thematischen Motive zu suggerieren, der gesamten Struktur Einheit zu verleihen und sich als Brennpunkt der Oper darzustellen vermag. Die beeindruckende Variationsfähigkeit kann durch die Vielfalt in der Entwicklung dieses Themas dargelegt werden. In der Originalform nimmt es sicherlich auf die Ängste des Protagonisten Dalibor Bezug, um dann - auf eine brillante Fanfare in G-Dur moduliert - zum melodischen Element für den Aufruf Jitkas zur Rettung ihres Helden zu werden. Eine spätere Modulation im ersten Akt wirft einen Schatten auf das Geständnis der Liebe Dalibors für Zdenì k und die Rechtfertigung des Racheakts nach der Ermordung des Freunds. Obwohl es sich um ein intimes Geständnis handelt, verwandelt die poetische Schönheit des Gesangs die Rachegelüste Miladas in den Wunsch, Dalibor zu befreien. Im übrigen erscheint es interessant, daß die Dalibors Gesang entspringende Melodie über die Sinnlosigkeit eines Lebens ohne Zdenì k Smetana das Thema für Ruhm und Fall der tschechischen Nation in Vysì hrad, dem ersten Teil der symphonischen Dichtung Mein Vaterland, geschenkt hat. Die lyrische Stimmung steigert sich noch intensiver im Liebesduett zwischen Dalibor und Milada am Ende des zweiten Akts, vielleicht dem raffiniertesten der von Smetana geschriebenen Duette. Die Qualität der Einfälle ist in der gesamten Oper eine außergewöhnliche, denn in Dalibor erreicht Smetanas melodischer Stil noch größere Höhen als in der Verkauften Braut, seine innerste Stimme ist hier noch präsenter, und die Originalität seiner Ausdrucksweise durchdringt das gesamte Werk. Der plötzlich zu Beginn des zweiten Akts erscheinende Unisonoentwurf könnte beispielsweise von Janácek stammen. Und sicherlich dürfen weitere außerordentlich interessante Augenblicke und Aspekte wie der Söldnerchor zu Beginn des zweiten Aktes nicht vernachlässigt werden. Außerdem scheint Smetana mit der aufgeblasenen Eitelkeit der Macht sein Spiel zu treiben, indem er den Auftritt der Richter im ersten Akt mit einem wackeligen Marsch in drei verschiedenen Tempi begleitet. In Dalibor bestehen hinsichtlich der Handlung und der dramatischen Entwicklung einige Probleme. Die einfache Dynamik der zwischen Milada und Dalibor aufgeblühten Liebe wird durch die Präsenz Zdenì ks (wenn auch nur als Toter) kompliziert. Für das Publikum der Uraufführung war die Eingangsszene natürlich langsam, und für die spätere Zuhörerschaft kommt das Finale allzu plötzlich. Abgesehen von allen anderen Überlegungen ist das wirklich Wichtige die Schönheit der Musik. Die Oper ist gleichzeitig eine Feier der Musik und mit ihren Symbolen - Zdenì k und seiner Geige eine Hymne an die tschechische Nation. Es stimmt, daß vielen von Smetanas Zeitgenossen die Komplexheit und Schönheit der Oper entging, was aber 11 sicherlich nicht auf Antonín Dvoøák zutrifft. Als Bratschist im Orchester der Uraufführung von Dalibor wußte Dvoøák die Belehrung durch diese außerordentliche Partitur zu erfassen, die in vieler Hinsicht seine Opernkompositionen beeinflußte. DALIBOR Un hymne à la musique i l’on considère Smetana comme étant le père d’un réveil national tchèque, il est tout à fait surprenant que les huit œuvres du compositeur soient si peu connues du public. Il est vrai que l’histoire, inexorable et impitoyable, a toujours déterminé la fortune de l’opéra. Si l’on excepte les contemporains de l’époque de Smetana, il faut reconnaître que l’on a accordé bien peu d’attention à d’importants auteurs de l’opéra tchèque comme Karel Sebor, Karel Bendl et Vilem Blodek, qui ont composé entre 1860 et 1880. Smetana lui-même a été victime de la nature discriminatoire du goût du public, même au plus fort de son succès. Les réactions qu’il eut à l’occasion des célébrations en l’honneur de la centième représentation de la Fiancée vendue, le 5 mai 1882, sont explicites. Bien que touché par l’affection du public et la récompense substantielle qui lui fut remise en titres et en argent, Smetana définit avec ambiguïté la Fiancée vendue “un simple jouet ”, une œuvre écrite presque pour contrarier ses détracteurs qui l’accusaient d’être incapable de composer dans un style plus simple. Smetana alla même plus loin en affirmant que les louanges exprimées pour la Fiancée vendue étaient une offense pour ses autres œuvres, notamment Dalibor, une œuvre dont il était sans aucun doute plus fier. L’on peut estimer qu’il y eut un lien étroit entre les célébrations pour la Fiancée vendue et les soucis dont il fut accablé et qui lui causèrent de graves problèmes de santé, sans doute accentués par la paranoïa croissante due aux succès toujours plus éclatants de Dvoøák. Paradoxalement, l’on peut affirmer que la fortune de la Fiancée vendue, dont l’extraordinaire succès reléguait inévitablement dans l’ombre les autres compositions de Smetana, conduisit celui-ci à l’effondrement. De fait, S Jan Smaczny Dozent für Musik an der Universität Belfast (Übersetzung: Eva Pleus) 12 après des débuts laborieux, ce fut la seule de ses œuvres à être intégrée au répertoire des théâtres. Seule la comédie brillante Le baiser égala par moments sa popularité. Le premier opéra de Smetana, Les Brandebourgeois en Bohème, obtint un grand succès la première année, en 1866, avec quatorze représentations, mais les nouvelles productions se firent de plus en plus rares, voire rarissimes. Quelques mois après les célébrations organisées pour la Fiancée vendue, Smetana fut profondément marqué par l’accueil réservé à son dernier opéra, Le mur du diable : pauvre en moyens et en idées, cette œuvre parut terriblement usée, notamment au regard de l’extraordinaire succès de l’opéra Dimitrij de Dvoøák, représenté le même mois. Le destin de Dalibor fit particulièrement souffrir Smetana, qui portait une affection particulière à cette œuvre. Le librettiste de ses derniers opéras, Eliska Krasnohorská, la considérait comme la “perle de l’opéra romantique tchèque ”. Smetana voulut faire connaître l’œuvre à son idole musicale, Franz Liszt, en la lui jouant au piano. Contrairement aux critiques pragois les plus sévères, Liszt apprécia Dalibor et n’y décela pas d’influence wagnérienne. Lorsque Miezyslav Kaminsky, ténor polonais en pleine ascension doté d’un grand talent musical et d’un profond instinct scénique, fut engagé au Théâtre Provisoire de Prague, Smetana espéra qu’il accepterait d’interpréter le rôle de Dalibor pour prouver enfin la “sincérité de l’œuvre ”. Malheureusement, celle-ci ne fut jamais représentée durant le séjour du ténor à Prague. La triste vérité est que Dalibor, à l’instar des autres opéras tragiques de Smetana Les Brandebourgeois en Bohème et Libuše, ne parvint jamais à captiver le public comme l’avaient fait ses deux opéras-comiques, la Fiancée vendue et Le baiser. La réaction d’un groupe de critiques fut sans doute déterminante. Le panorama culturel de Prague, notamment dans le domaine de la musique, était déchiré par de multiples contrastes, dont l’un des principaux concernait l’influence exercée par Wagner. Quoique Smetana admirât l’œuvre de Wagner, il ne fut certainement pas un imitateur servile : il était au contraire bien conscient des dangers que présentait l’utilisation des modèles wagnériens à une époque où l’on jetait justement les bases d’un style particulier de l’opéra tchèque. Néanmoins, ce sentiment n’épargna pas à l’auteur de Dalibor l’accusation, de la part de bon nombre de critiques, d’avoir conçu cet opéra dans un style wagnérien : l’intrigue, en partie tirée du mythe, et l’adoption d’un système de métamorphoses thématiques proches des leitmotivs furent le prétexte de cette accusation ; dans ce cas, Dalibor serait vraiment apparu comme une tentative pour dépasser Tristan et Iseut. Aujourd’hui, ces affirmations semblent absolument insignifiantes, mais elles eurent à l’époque un profond impact sur le public. Smetana avait une idée précise des motifs du maigre succès de Dalibor auprès du public : “ Je comprends seulement maintenant que notre public manque de raffinement et d’éducation à la musique, malgré tout ce qu’une ville comme Prague peut offrir comme institutions musicales, sociétés de concerts, production et théâtres… ”. Jugement sans doute caustique, mais non pas dénué d’un fond de vérité. Le public de Prague était passionnément épris du divertissement, des airs en rime sur des motifs populaires et des chœurs ronflants. L’on retrouvait tous ces éléments en abondance dans les Brandebourgeois et dans la Fiancée vendue. Dans Dalibor, dont la matière et la sensibilité du protagoniste étaient autrement plus élevées, Smetana avait soigneusement évité de toucher ces cordes. Il ne fait aucun doute que dans sa grande majorité, le public ne comprit pas ce que le compositeur lui offrait. Dalibor est sans aucun doute l’opéra le plus extraordinaire de Smetana et dépasse en raffinement les deux premières œuvres pour le théâtre. 13 Dès le commencement, Smetana entre dans le vif du sujet ; en effet, le tissu musical est développé avec une grande maîtrise, évitant de faire appel à une ouverture facile pour capturer l’attention du public. La gamme ascendante et sourde qui émerge dès les premières mesures est le substrat musical capable de suggérer une grande partie des motifs thématiques, de donner une unité à l’ensemble de la structure et de se poser en point crucial de l’œuvre. L’impressionnante capacité de variation peut être mise en valeur par la variété des développements sur ce thème : dans la version originale, il se réfère certainement à l’angoisse du protagoniste Dalibor ; modulé en une fanfare brillante en sol majeur, il devient un élément mélodique pour rappeler à Jitka le sauvetage de son héros. Une ultérieure modulation dans le premier acte jette une ombre sur la confession d’amour qu’éprouve Dalibor pour Zdenì k et sur la justification pour l’acte de vengeance qui a suivi l’assassinat de son ami. Bien qu’il s’agisse d’une confession intime, la beauté poétique de son chant transforme les desseins de vengeance de Milada en désir de libérer Dalibor. L’on remarquera que la mélodie qui se dégage du chant de Dalibor sur l’inutilité d’une vie sans Zdenì k a fourni à Smetana le thème pour la gloire et la chute de la nation tchèque dans Vysì hrad, le premier des poèmes symphoniques de Ma vlast. Le lyrisme se fait encore plus fort et intense dans le duo d’amour entre Dalibor et Milada, sans doute le plus raffiné de tous ceux qu’écrivit Smetana, à la fin du deuxième acte. La qualité de l’invention est extraordinaire du début à la fin de l’opéra : dans Dalibor, le style mélodique de Smetana surpasse même celui de la Fiancée vendue, sa voix plus intime est encore plus présente et l’originalité de sa rhétorique imprègne toute l’œuvre ; le dessin musical à l’unisson qui surgit soudain au commencement du deuxième acte, par exemple, pourrait avoir été composé par Jánaèek. L’on ne saurait négliger d’autres moments et aspects exceptionnellement intéressants, comme le chœur des mercenaires au début du deuxième acte ; au premier acte, Smetana semble se jouer de la vanité hautaine du pouvoir en accompagnant l’entrée des juges d’une marche estropiée cadencée en trois temps. D’autres problèmes sont liés à la fois à l’intrigue et au développement dramatique : la dynamique essentielle de l’amour né de la rencontre entre Milada et Dalibor est compliquée par la présence de Zdenì k, bien que celui-ci soit mort. Il ne fait aucun doute que le public qui assistait à la première représentation de l’opéra jugea la scène initiale trop lente et le final trop soudain. Toute autre considération mise à part, l’élément principal est représenté par la beauté de la partition : l’œuvre est à la fois une célébration de la musique et, au travers de ses symboles — Zdenì k et son violon —, un hymne à la nation tchèque. S’il est vrai que bon nombre de contemporains de Smetana ne saisirent pas la complexité et la beauté de cet opéra, il n’en fut pas de même pour Dvoøák. Violoniste de l’orchestre lors de la première représentation de Dalibor, Dvoøák sut recueillir l’enseignement de cette extraordinaire partition qui influença sous de nombreux aspects ses compositions pour la scène. Jan Smaczny Professeur de musique à l’université de Belfast (Traduit par Cécile Viars) 14 Dagmar Schellenberger Valeri Alexejev 15 Beneš (Milada travestita). Dalibor ha chiesto di avere un violino da suonare in prigione: Beneš dà ordine a Milada di portarglielo. Nella sua cella, Dalibor vede il fantasma di Zdenì k che suona il violino, ma la visione è interrotta dall’arrivo di Milada. Ella gli rivela la sua vera identità, gli chiede perdono per le sue accuse ed esterna il suo amore per lui. TRAMA PRIMO ATTO Nel palazzo reale, Dalibor è in attesa di essere processato per l’uccisione del burgravio di Ploškovice. Nel popolo che affolla l’aula - e che è in gran parte in suo favore vi è Jitka, un’orfanella amica di Dalibor. Il re legge l’accusa, poi invita Milada, sorella del burgravio assassinato e principale accusatrice di Dalibor, a raccontare come Dalibor attaccò e uccise suo fratello. Viene condotto Dalibor, che suscita mormorii di ammirazione per la nobiltà del suo portamento. Presenta la sua difesa: egli agì per vendetta. Il burgravio aveva fatto prigioniero e giustiziato Zdenì k, suo più caro amico e famoso violinista. Quando Dalibor si era offerto di pagare un riscatto per l’amico, il burgravio gli aveva fatto pervenire la testa decapitata di Zdenì k, in cima ad una lancia. Nell’udire quella storia, Milada si sente impietosire; l’orgoglio e il senso di giustizia di Dalibor, tuttavia, lo spingono ad un atto di aperta sfida nei confronti dell’autorità reale. Il re lo condanna al carcere a vita, nonostante Milada ormai lo supplichi di averne pietà. L’odio che provava nei confronti dell’uccisore di suo fratello si è infatti tramutato in amore. Jitka ha ora in lei un’inaspettata alleata ed insieme studiano un piano per liberare Dalibor. TERZO ATTO È notte fonda; il re ha riunito i suoi giudici in una seduta di emergenza. Budivoj li informa che il popolo è in fermento per liberare Dalibor e Beneš rivela che il suo aiutante è scomparso in circostanze sospettose. Il re a malincuore ordina che Dalibor sia giustiziato. Budivoj e le sue guardie riescono a sventare la fuga del prigioniero. Fuori dal carcere, Milada, Vítek e Jitka, con il loro gruppo di ribelli, si preparano all’assalto: quando sentono il rintocco di una campana e un coro di monaci, capiscono però che i loro piani sono falliti e che Dalibor verrà giustiziato. Milada riesce ad entrare nel castello e a raggiungere Dalibor, ma, mortalmente ferita, muore fra le sue braccia. Disperato, Dalibor si getta sulla spada di un soldato e muore trafitto. SECONDO ATTO Fuori dal carcere, Jitka incontra il suo fidanzato, che è a capo del gruppo di soldati ribelli che vuole liberare Dalibor. Jitka gli rivela che Milada è passata dalla loro parte e si è introdotta nella prigione in abiti maschili. Budivoj, capo delle guardie, mette in guardia Beneš, il carceriere, di una possibile sommossa per liberare Dalibor. Tra i sospetti vi è anche il nuovo assistente di 16 violin, but his reverie is interrupted by Milada’s arrival. She reveals to him her true identity, asks his mercy for her accusations and tells him of her love. SYNOPSIS ACT THREE Late at night the King has summoned an emergency meeting of his judges. Budivoj reports that the people are scheming Dalibor’s escape, and Beneš reveals that his new apprentice has suspiciously disappeared. The King regretfully orders Dalibor’s execution. Budivoj and his guards succeed in preventing Dalibor’s escape. Outside the prison, Milada, Vítek, Jikta and their army of rebels are preparing to charge: hearing the tolling of a bell and a chorus of monks, however, they realize that their plan has failed and that Dalibor will be executed. Milada succeeds in entering the castle and reaching Dalibor, but, mortally wounded, dies in his arms. Dalibor, heart-broken, flings himself against a soldier’s sword and finds death. ACT ONE In the king’s palace, Dalibor awaits judgement for the killing of the Burgrave of Ploškovice. Among the largely sympathetic crowd awaiting his sentence is Jikta, an orphan whom Dalibor has befriended. The King reads the charges, then asks Dalibor’s principal accuser, Milada, sister of the dead Burgrave, to tell how Dalibor attacked and murdered her brother. Dalibor is brought in, among admiring comments on his noble bearing. He states his defence: the killing was done out of revenge. The Burgrave had captured and executed his best friend, the famous violinist Zdenì k. When Dalibor had offered to pay ransom for his friend, the Burgrave had returned Zdenì k ’s severed head at the end of a lance. As the story unravels, Milada’s feelings towards Dalibor begin to change. Dalibor’s pride and sense of justice, however, lead him to openly defy the King’s authority. The King sentences him to life imprisonment, despite Milada’s pleas for mercy. She now finds herself in love with her brother’s killer. Jitka discovers in her an unexpected ally: together they plan to free him from prison. ACT TWO Outside the prison, Jikta meets her fiancé, who is at the head of the secret army that will help Dalibor escape. She reveals to him that Milada has changed sides and has entered the prison in male disguise. Budivoj, the captain of the guards, warns the jailer, Beneš, of a possible popular uprising to free Dalibor. He suspects also Beneš’s new assistant (Milada in disguise). Dalibor has asked for a violin to play while in prison, and Beneš orders Milada to take it to him. In his cell, Dalibor is having a vision of Zdenì k playing 17 Männerkleidung in das Gefängnis geschlichen hat. Der Anführer der Aufseher, Budivoj, warnt den Kerkermeister Benes vor einem möglichen Aufstand zur Befreiung Dalibors. Zu den Verdächtigen gehört auch der neue Helfer von Benes (in Wirklichkeit die verkleidete Milada). Dalibor hat um eine Geige gebeten, auf der er im Kerker spielen möchte; Benes befiehlt Milada, ihm eine solche zu bringen. In sener Zelle sieht Dalibor den Geist Zdenì ks, der auf der Geige spielt, aber diese Vision wird durch Milada unterbrochen. Sie entdeckt ihm, wer sie ist, bittet ihn für ihre Anschuldigungen um Vergebung und bringt ihm ihre Liebe zum Ausdruck. DIE HANDLUNG ERSTER AKT Im Königspalast erwartet Dalibor seinen Prozeß wegen der Ermordung des Burggrafen von Ploskovice. Unter dem die Halle füllenden Volk, das zum Großteil für Dalibor ist, befindet sich Jitka, eine Dalibor zugetane Waise . Der König verliest die Anklage und fordert dann Milada, die Schwester des ermordeten Burggrafen und hauptsächliche Anklägerin Dalibors, auf, zu erzählen, wie dieser ihren Bruder angriff und tötete. Dalibor, der mit seiner edlen Haltung ein bewunderndes Murmeln hervorruft, wird hereingeführt. Seine Verteidigung lautet, daß er aus Rache handelte. Der Burggraf hatte Zdenì k, senen besten Freund und berühmten Geiger, gefangen genommen und hingerichtet. Als Dalibor angeboten hatte, ein Lösegeld für seinen Freund zu bezahlen, hatte ihm der Burggraf das auf einer Lanze aufgespießte abgeschlagene Haupt Zdenì ks geschickt. Als Milada diese Erzählung hört, kommt Mitleid in ihr auf, aber Stolz und Gerechtigkeitssinn Dalibors bewirken, daß er die königliche Gewalt offen herausfordert. Obwohl Milada nun um Mitleid fleht, verurteilt ihn der König zu lebenslanger Haft. Der Haß, den Milada gegenüber dem Mörder ihres Bruders verspürte, verwandelt sich in Liebe. Jitka hat in ihr nun eine unerwartete Verbündete; gemeinsam machen sie einen Plan, um Dalibor zu befreien. DRITTER AKT Es ist tiefe Nacht; der König hat seine Richter in einer Notsitzung einberufen. Budivoj teilt ihnen mit, daß sich das Volk in Aufruhr befindet, um Dalibor zu befreien, und Benes erklärt, daß sein Helfer unter verdächtigen Umständen verschwunden ist. Der König befiehlt schweren Herzens Dalibors Hinrichtung. Budivoj und seinen Wächtern gelingt es, die Flucht des Gefangenen zu vereiteln. Vor dem Kerker bereiten sich Milada, Vítek und Jitka mit ihrer Rebellengruppe auf den Angriff vor. Als sie das Läuten einer Glocke und einen Chor der Mönche hören, wird ihnen aber klar, daß ihre Pläne mißglückt sind und Dalibor hingerichtet werden wird. Milada gelingt es, in das Schloß und zu Dalibor zu gelangen, aber sie stirbt, tödlich verletzt, in seinen Armen. Dalibor stürzt sich verzweifelt in das Schwert eines Soldaten, das ihn durchbohrt. ZWEITER AKT Außerhalb des Gefängnisses trifft Jitka ihren Verlobten, der an der Spitze der Gruppe aufständischer Soldaten steht, die Dalibor befreien wollen. Jitka teilt ihm mit, daß Milada zu ihrer Seite übergelaufen ist und sich in 18 assistant de Beneš (Milada déguisée en homme). Dalibor a demandé qu’on lui porte un violon pour en jouer dans sa cellule et Beneš ordonne à Milada de satisfaire à son désir. Dans sa prison, Dalibor aperçoit le fantôme de Zdenì k jouant du violon, mais sa vision est interrompue par l’arrivée de Milada. Celle-ci lui révèle sa véritable identité, lui demande pardon de l’avoir accusé et lui déclare son amour. TRAME ACTE I Dans le palais royal, Dalibor attend d’être jugé pour l’assassinat du burgrave de Ploškovice. Parmi la foule présente dans la salle, dont la majeure partie le soutient, se trouve Jitka, une jeune orpheline amie de Dalibor. Le roi lit l’accusation puis invite Milada, sœur du burgrave assassiné et principale accusatrice de Dalibor, à raconter comment Dalibor attaqua et tua son frère. L’on amène Dalibor dont l’allure noble suscite des murmures d’admiration. Pour sa défense, il déclare avoir agi par vengeance car le burgrave avait fait arrêter et exécuter son plus cher ami Zdenì k, un célèbre violoniste. Quand Dalibor s’était offert de payer une rançon pour libérer son ami, le burgrave lui avait fait parvenir la tête coupée de Zdenì k empalée sur une lance. En entendant ce récit, Milada s’émeut ; mais l’orgueil et le sens de justice de Dalibor le poussent à défier ouvertement l’autorité royale. Le roi le condamne à la prison à vie bien que Milada l’ait supplié d’avoir pitié de lui. La haine qu’elle éprouvait envers l’assassin de son frère s’est en effet transformée en amour. Jitka trouve désormais en elle une alliée inattendue et toutes deux étudient un plan pour libérer Dalibor. ACTE III Au milieu de la nuit, le roi a réuni d’urgence ses juges. Budivoj leur apprend que le peuple s’apprête à se révolter pour libérer Dalibor ; de son côté, Beneš leur révèle que son assistant a disparu dans des circonstances suspectes. A regret, le roi donne l’ordre d’exécuter Dalibor. Budivoj et ses gardes parviennent à déjouer la fuite du prisonnier. Hors de la prison, Milada, Vítek et Jitka, accompagnés de leur groupe de rebelles, se préparent à l’assaut : au son d’une cloche et d’un chœur de moines, ils comprennent pourtant que leur plan a échoué et que l’on s’apprête à exécuter Dalibor. Milada parvient à entrer dans le château et à retrouver Dalibor mais elle expire dans ses bras, mortellement blessée. Désespéré, Dalibor se jette sur l’épée d’un soldat et succombe lui aussi. ACTE II Devant la prison, Jitka rencontre son fiancé, le chef du groupe de soldats rebelles qui souhaite libérer Dalibor. Jitka lui apprend que Milada s’est jointe à eux et qu’elle s’est introduite dans la prison dans des vêtements d’homme. Le chef des gardes, Budivoj, met en garde Beneš, le geôlier, contre la possibilité d’une émeute visant à libérer Dalibor. Parmi les suspects se trouve aussi le nouvel 19 Bedøich Smetana DALIBOR LIBRETTO BY JOSEF WENZIG LIBRETTO a osvobodíme jej z hrobových skal! (Trubky zazní za jevi¢ stìm; ohla¢ sují p¢ ríchod krále a soudcù.) Pochod. P¢ ríchod krále a soudc°u. DÌJSTVÍ PRVNÍ Hradní dvur obsazený stráží. V pozadí královský trùn. Lid, mezi ním Jitka. 3 2.výstup P¢ rede¢ slí. Král Wladislaw. PREDEHRA 4 Wladislaw - Ji¢ z víte, jak to krásné království divokých vᢠsní obìtí se stalo, a víte té¢ z, jak dlouho Dalibor svévolnì ru¢ sí mír, který jsem hledal, a novým zlo¢ cinem se provinil. Hrad Ploskovice p¢ repad’ s vojsky svými, pobo¢ ril hradby i purkrabího zabil. Však koneènì jej poko¢rila vojscka, která jsem vyslal, Miladou pobádán, padlého sestrou. A¢ z tu Dalibor po stra¢ sné, krvavé se bitvì poddal. Je v moci mé, nad ním rozsoudí král! By ale soud vᢠs moh’ být spravedlivý, p¢ red Daliborem sly¢ ste Miladu! 1. výstup Lid. Jitka. 1 Lid - Dnes ortel bude provolán a právu viník v ob¢ et dán! Dalibor! Dalibor! Však nechat se i proh¢ re¢ sil, udatný, slavný rek to byl. Dalibor! Dalibor! 2 Jitka - (zamy¢ slená o samot¢ e) Opu¢ st¢ eného sirotka malého na¢sel ve troskách starobylých st¢ en, ujal se mne a pod ochranou jeho jsem vstoupila v z¢ivota krásný sen. On cht¢ el mi v pout z¢ivota chot¢ e dáti, jen¢ z nejdra¢ zs¢ím byl du¢si pokladem, m¢ ela jsem s¢t¢ estí nejvy¢s¢sího znáti ve vlastním dom¢ e s drahým man¢ zelem A ted’ - ó b¢ eda mi v nep¢ ratel padne moc, snad c¢asn¢ e - b¢ eda mi jej pojme hrobu noc. Lid - Dnes ortel bude provolán a právu viník v obìt dán! Dalibor! Dalibor! Jitka - Však ne!Ze z¢alᢠre pokyne zᢠre! To¢ z pádím na peruti vìtrové dál. A v hrobu noc temnou jdou druhové se mnou - 3.výstup P¢ rede¢ slí. Milada. 5 Wladislaw - Ji¢ z uchopte se slova a vypravujte nám; zde soudcù sbor zasedne, by dal za právo vám. Milada - Mùj duch se dìsí, n¢adra má se dmou, co dím, je pláè nad ztrátou ukrutnou! Lid - Slzami odìla hnìv! Jitka (pro sebe) - Strachem ji¢ z mi stydne krev! Milada (vzchopiv¢ sí se v¢sí silou) 21 Jitka (pro sebe) - Strachem stydne moje krev. Wladislaw - Milado, tìšte se! Kdo ranil vás, je vìznìm mým. Mé zbrani z¢ehnal Pán a tím i vám i zemi po¢ zehnal. At vstoupí Dalibor sem ku p¢ riznání! Milada - Mám jej snad z¢ ríti? Tot bratra vrah, jak bou¢ rí krev mi v útrobách! Jitka - Stúj Búh nyni p¢ ri mné! du¢si mou spas. Zjeviti nesmím n¢ader mých hlas. Milada - Jak bou¢ rí krev mi v útrobách! Mám jej snad z¢ ríti? Tot bratra vrah. Volám! O mìjte slitování! Vysly¢ ste z¢alné lkání! Smilování! Slitování! 6 Pohasnul den a v hradì v¢ se bla¢ zilo se snem. Netu¢ sil nikdo zradu, je¢ z bdìla pod hradem. V tom hromové jsem rány zaslechla z blízkých hor, probudí mne výk¢ riky ze sna: Dalibor! Dalibor! A r¢in¢ cely me¢ ce z té krvavé se¢ ce i z dáli i blí¢ z. Vpo¢ záru a kou¢ ri zde vojska bou¢ rí pod hradbami ji¢ z. Bloudím a drahého bratra pod hradem volala jsem, tam v dáli klopýtaje krᢠcel s oddaným pano¢ sem. Z otev¢ rené hrozné rány krev se lila z rudých z¢il, otev¢ rel ústa - sklesl a du¢ si vypustil. Pano¢ s ho¢ rekující mne odvedl v lesní s¢um, tajnými cestami jsem u¢ sla nep¢ rátelùm. A nyní svou p¢ red vámi skláním skrᢠn, o poslední oloupená. Žaluji na¢n. Ont zlo¢ cincem, neb jeho mstou ne¢ stastna jsem. Dalibor! Dalibor! Lid - Soucit budí tento zjev. 4.výstup P¢ rede¢ slí. Dalibor. (Dalibor vstoupí s lehkými okovy na rukou a postoupí tiše i hrdì prìd trùn královský.) 7 Milada (p¢ rekvapena) - Jaký to zjev! To netušil mùj zrak. Lid (mezi sebou) - Bud’ viny jeho sebevíc, jak klidnì pat¢ rí osudu vst¢ ríc. Wladislaw - Na ob¢ zalobu tuto odpovìz! Hrad Ploskovice tajnì p¢ repadl jsi, hrad pobo¢ ril jsi a purkrabího zabil jsi. Omluv se, mù¢ zeš-li, p¢ red námi hned! 8 Dalibor - Zapírat nechci, nejsemt zvyklý lháti. Ját p¢ rísahal jsem pomstu a p¢ rísahu co øádný mu¢z jsem splnil. V¢ zdy odolal jsem c¢arozraku z¢en. Po p¢ ríteli mùj duch toliko tou¢ zil. Mé p¢ rání splnìno, p¢ rátelství sen jsem snil, u Zde¢ nka v n¢ader tù¢ n se hrou¢ zil. 22 Lid - Tím slovem na se me¢ c vystasil! Soudcové - Tys ortel smrti sobì sám prohlásil! Dalibor - Ni¢ cím je mi z¢ivot, co Zdenìk mùj klesl, vše jedno, zda zemru snad zítra c¢i dnes! Milada - Co dí? Co dí? Dalibor - A¢ z do dna vy¢ cerpán radosti pohár, to¢ z zahodím od úst ten šalebný dar! 10 Jedenze Soudcù - Tak, Dalibore, zní soud jednohlasnì: V z¢alᢠri temném hy¢ n, a¢ z dokonᢠs! Lid - Ji¢ z z¢ ríti nemá slunce tvᢠr, milosti jej se netkla tvᢠr! Dalibor - Slyšels to p¢ ríteli, tam v nebes kùru? Ji¢ z chystají mi cestu k tobì zas! Ji¢ z cítím povznesen se vzhùru, ji¢ z z¢ rím tì v oblacích, slyším tvùj hlas! Ji¢ z piju opìt piju strun tvých c¢arozvuky! Slavnìj ne¢ z zde zní píse¢ n tvoje tam! Lid - Jaký to zjev, jaký to zjev! Dalibor - Nu¢ z, ved’te mne v z¢alᢠre noc a muky, tou cestou pílím k nebes výšinám! (Odejde.) Lid - Jaký to zjev, jaký to zjev! Slavný rek, udatný rek to byl! Kdy¢ z Zdenìk mùj v svatém nadšení zvuk rajský loudil v mysl rozháranou, rozplýval jsem se v sladkém tou¢ zení, povznesen tam, kde hvìzdy jasné planou. Však slyš! U¢ z dávný c¢as jsem vedl hádku s litomì¢ rickou radou zpyšnìlou a opìt v boj jsem šel, po boku Zdenìk, mùj drahý Zdenìk, nerozdílný druh. Boj zu¢ rit po¢ cal hnìvem. Zdenìk pad’ v nep¢ rátel moc a váše¢ n surová mu stala hlavu, mnì pak v potupu ji narazila na hradbách na kùl. Hrùz obraze, který jsem pníti tam musel z¢ ríti! Tím zdìšením nevím, zda bdím! Marnì oko slze volá, by si ulevila n¢adra má! Milada - Ta z¢aloba pronikla n¢adra moje! Dalibor - Tu p¢ rísahal jsem pomstu, hroznou pomstu! Že Ploskovice Litomì¢ricùm pomáhaly - polehly popelem. Pochodeò k hrobu Zde¢ nka! Purkrabí pak splatil svou krví hlavu Zde¢ nkovu. 9 Wladislaw - Zlo¢ cinem tak pomáhals sobì sám! Dalibor - Mu¢ z právo k tomu vzíti si nenechá! Wladislaw - Tys vedl vzpouru proti svému králi! Dalibor - Moc proti moci! Tak to kᢠze svìt! Prohláším sám to, nepadnu-li zde, za Zde¢ nka pykat musí Litomì¢ r! Akdybys v tom mi, králi v cestì stál, na trùnì bezpe¢ cnì bys nesedìl! Milada - Co dí? 5.výstup Milada, Jitka, Wladislaw, soudcové, lid. 11 Milada - (u¢ z se nemù¢ ze p¢ remoci, p¢ red králem a soudci) U svých mne zde vidíte nohou! 23 Milada - Neznám tì! Jitka - Jindy povím víc! Milada - Co z¢ádáš!? Jitka - Skutkem díky r¢íc! Ze z¢alᢠre pokyne zᢠre, to¢ z pádím na peruti vìtrové dál. Milada - A z hrobu ¢zalá¢re pokyne zá¢re to¢ z pádím na peruti vìtrové dál. Obì - A v hrobu noc temnou jdou druhové se mnou a osvobodíme jej z hrobových skal! Odpustte mu tak jako já! Jen dobré chtít ty o¢ ci mohou, odpustte mu, at volnost má! Soudcové - On hrozil krále s¢edinám, za zlo¢ cin ten at padne sám! Milada - U svých mne zde vidíte nohou! Jen dobré chtít ty o¢ ci mohou! Odpustte mu, at volnost má, Milost, milost, odpustte mu tak jako já! Soudcové - On hrozil krále šedinám za zlo¢cin ten at padne sám! Milada - Milost, milost, at volnost má, odpustte mu tak jako já! Wladislaw - Po¢ rádek, zákon vlásti musí, zlo¢ rádem zem nejvíce zkusí, to¢ z povinnost nám zákonem, bychom p¢ reslechli n¢ader hlasy, zlo¢ cin nesmí¢ rí, neuhasí, jen kdo jej schvátí ortelem. (Odejdou, kromì Jitky a Milady). DÌJSTVÍ DRUHÉ Silnice v dolním mìstì s krìmou. 1.výstup Zbrojnoši, pozdìji Jitka a Vítek. 6. výstup Milada, Jitka. 13 Zbrojnoši - Ba nejveselejší je tento švet, kdy¢ z se touláme z r¢íše do r¢íše. Tralala, tralala! A komu leb vejpùl, darmo tu klet, ten at si to za uši vpíše, Tralala, tralala... (Zbrojnoši jdou do kr¢ cmy.) 14 Jitka (Vstoupí mezi zp¢evem) Dle této písn¢e poznávám je v¢ zdy. (Vítek vystoupí z kr¢ cmy.) Že jdeš koneènì! Vítek - Jitko, dítì mé! Jenom ml¢ c, jenom ml¢ c, drahoušku mùj, dlouho z¢e nejdu ji¢ z domù. Ját mám zato vojsko, lid nynì svùj, jen¢ z se neleká blesku, hromu! 12 Milada (nezpozoruje Jitku) Jaká to bou¢ re n¢adra mi plní z¢e krev mi v z¢ilách staví bìh! On usmrtil, zabil mi bratra, a p¢ rec mne k n¢ emu cosi má. Ó nehroz, ó nehroz mi, ó brat¢ re! A jen vinou mou od¢ nat mi nyní zcela, zhynouti má ted pro mne jen v z¢alᢠri a v mu¢ círnách tìla, jen pro mne zhynouti má! Jitka - Tot láska! Láskou rady zví¢ s, a vzmu¢ z se, vzumu¢ z se k c¢inu ji¢ z! 24 a jdìm na pomoc! Jitka (ukazujíc na jinou stranu mìsta) Pro¢ c jsi nep¢ rišel hned ke sta¢ renš té, jež mne chránila, mùj drahoušku? Vítek - Ted’ právé jíti jsem chtìl, tu pøišla jsi sama, mé zlato! Oba (dívají se na sebe v lásce) Ta duše, ta touha, to srdce, ten èar, tot lásky mé je velký dar… Ani za øíši jej nedám na zmar! 15 Jitka - Je Daliborùv osud tobì znám? Vítek - Vždyt o nìm slyším, kam jen hlavu dám! Jitka - Slyš tedy dále! Žalobnici Bùh cit vnuknul v òadra. Oplakává ted’ svùj èin, a láskou k nìmu zahoøela! Varyto v rukou jako hoch žebrácký se vkradla tajnì na královský hrad, klamajíc strážce milým lichocením. A okolo stráží tam chodí a hrá, a slídí a zvídá a pátravì se ptá! Oba - A okolo stráží tam chodí a hrá, a slídí a zvídá a pátravì se ptá. Jitka - Však až dá nám zprávu Vítek - tu ještì noc Jitka - pøikroème k dílu Vítek - a jdìm na pomoc! Oba - Však až dá nám zprávu, tu ještì noc pøikrorèmež k dílu 2.výstup Zbrojnoši, pøedešlí. 16 Zbrojnoši - Ba nejveselejší je tento svìt, když se touláme z øíše do øíše. (Zbrojnoši vystoupí z krèmy a vesele se smìjí.) Vítek - Pøistupte, bratøi a pozdravte Jitku, pomocí její zas jsme cíli blíže! Zbrojnoši - sláva tobì, sláva tobì, Vítka nevìsto milá, na niž co na jarní rùži oko rádo pohlédá! Jitka - Sláva vám bud’, sláva vám, muži meèe, muži prapora, na nìž co na lesa doubce oko rádo pozírá! Vítek, Zbrojnoši - Sláva tobì, sláva tobì! Tož v hodinu štastnou jsme opìt ve spolek slouèeni, u vìrném a stateèném kole pro vìc svou nadšeni. ó nebe, kéž se to zdaøí, vzdor hrozbám neštìstí. Bud’me statní, bud’me jaøí, nuž a slavme vít¢ezství! Vítek - Jitku ted’ povedu domù, vy Však pijte až po noc! Plány na¢se nevyzrad’te, kvaste, hodujte, Však platte, smíchu, zpìvu moc a moc! (S jitkou odejde.) Zbrojnosí - Vizte, tam jdou již, hled’te, tam kráèí, pìkn´y párek to bude vám! Na jeho blaho prázdnìte èíše, až budou sudy všechny ty tam, všechny ty tam! 25 2.výstup Beneš. (Vracejí se do krìmy.) Promìna 1. Vnitøní prostora hradu s bytem žaláøníka. V pozadí stráže. 18 Beneš (sám) - Ach, jak tìžký žalárníka život jest, jak truchlivý! Dvéøe praští, okov øinèí, zdí tu stín jen šedivý. Sám se zdám v žalári býti, vùkol vida bídu jen, a kdyby i òadra pukla, musím zdát se zkamenìn! 1.výstup Budivoj, Beneš. 17 Budivoj - Nejvìtší bedlivosti tøeba, velkýt je Daliborùv pluk, a zanedbáš-li, èeho tøeba, zastihne smrt tì ze sta ruk! Beneš - Pane, na mne spolehejte, slibu mému víry dejte! (Mezitím šla okolo Milada za muže pøestrojená, s taškou a košíkem potravinami naplnìným do bytu žaláøníka.) Budivoj - Jaký to hoch jest, jejž odcházet zøím!? Beneš - Bez strachu bud’te, pane, vše povím! Ten hoch zde je ubohý žebrák, který se zvuèným varytem a s písnìmi v hrdélku mladém od stráží byl propuštìn sem. Nemám ni dítek, ni ženy, a stáøím již mi tuhne krev, tož vzal jsem k sobì hocha toho, by potìšil mne jeho zpìv. A vìru, pane, vìøte mnì to, on slouží hbitì, rád mne má. vsadím se, že nemá již nikdo takového sluhu jako já. Budivoj - Leè pøíliš sobì nehov, starèe, velk´yt je Daliborùv voj, a zanedbáš-li èeho tøeba, skonèí ten boj se truchlivì! (Odejde vážnì.) 3.výstup Beneš. Milada. 19 Milada (vybìhne z bytu žaláøníkova) Hotovo všechno, sednìte sem! Uzenek hojnost, maso tu dobré, máslo, chléb, sýr tu, piva zde všem; jezte a pijte, každý si vezmi co vem! Beneš - Velikou mám z tebe radost, chlapèe mùj, když t¢e tak z¢rím! Chovej vždy se statnì, já ti budu otcem peèlivým! Milada - Hotovo všechno, sednìte sem! Beneš - Uzenek hojnost, maso tu dobré, máslo, chléb, sýr tu, piva zde všem! Milada - Jezte a pijte, vezmi co vem! Beneš - Ještì mám cos na starosti, než zasednu k hodu sem! 26 a srdce mi buší, ted’ Bùh pøi mnì stùj. ó nebe, nebe! Dej, at tak se stane! Slyšíš-li výkøik lidských òader snad, kéž hlas mùj k tobì prorazí, ó Pane! Dej svobody, at záø se mu dostane! Slyšíš-li výkøik lidských òader snad, ó nebe, nebe, dej svobody, at záø, ta jasná záø mu zaplane! Milada - Noc již rozpjala svá køídla po nebi i nad svìtem! Beneš - Byt i mdlé mé nohy byly, to Však vykonat musím. Milada - Nemoh’ bych snad jíti za vás? Mladých nohou nešetøím. Beneš (s radostí) - Chtìl by snad, ó chlapèe? Milada - Rád bych! Beneš - Snad to dovoluje øád. Milada - Budivoj odešel dávno, rcete jen a pùjdu rád! Beneš - Poslechni! Dolù sedmdesát schodù… Tamt Dalibor! Milada (vesele, tají Však radost) - Že Dalibor? Beneš - Ty znáš rytíøe? Milada - Vidìl jsem jej pouze jednou! Beneš - Budít on lítost mou. V zoufalství zpola prosil mne èasto o nìjaké housle, by hrou si zkrátil dlouhou, pustou chvíli! Kterýpak Èech by hudbu nemìl rád! Za mladých let jsem hrával na nì též, trvám, že ve starém harampádí ty housle ještì! Pùjdu pro nì hned; ty mu je dáš! Milada - Dobrá já mu je dám! (Beneš odejde do svého bytu.) 5.výstup Milada, Beneš. (Beneš vstoupí.) 21 Beneš - Zde jsou ty housle! Vezmi lampu též, neb tmavé jsou ty dlouhé schody dolù. První jen branku zavru za tebou, poèkám pak tu! K druh´ym pak brankám dál již dojdeš závorami pevnì zavøenými. Posuò je zpìt a nemeškej tam dlouho! Už rád bych s druhy svými hodoval. Ty Však se tøeseš! Milada - Mne pojímá radost, kterou pocítí rytíø Dalibor! Beneš a Milada - Ano, bude míti radost, jeho sen že vyplnìn. Snadòìi svùj osud snese jeho duch tak posilnìn. (Odejdou.) 4.výstup Milada. 20 Milada - Jak je mi? Ha, tak náhle pøišla již ta chvíle dávno s nebe vyprošená, kdy bude dáno mi jej vidìt, mluvit s ním! Radostí nesmírnou se kalí zrak mùj, 27 3 Milada (podává Daliborovi housle) Vem tento chudý dárek z ruky mé. Dalibor (chytí housle, aniž by pohlédl na Miladu) Koneènì mám ty dávno ždané housle! Ó Zdeòku, Zdeòku, Zdeòku! Leè kdos ty? O rci mi, chlapèe, povìz mi, kdo že jsi ty? Milada - Ty ptáš se, kdo že jsem? Aj, nepovšimnuls tenkrát sobì tváøe mé? Nuž vìz! Jsem ubohá ta žena, jež tì z pomsty udala a s tebou stála vyslyšeti soud! Má vina to, že zde v žaláøi hyneš! Dalibor - Milado! Možná-li to? Milada - Jsem Milada! Leè spatøit tì jen jednou staèí v té svaté chvíli, dím to bez obalu, a hoøce, vøele pykat èinu, tak kázal mocný nebes Pán! Co lyrník jsem se v hrad ten vloudila, nic nedbala na život, svobodu, jen abych správce ziskala, až mne poslal s houslemi. Leè tajnì nesu též, co tøeba k útìku a pomoci, bys møíž v té zdi moh’ proraziti veskrz a otevøít si cestu k svobodì! Dalibore, odpust, prosím, divokou tu pomstu mou. Žal hluboký v òadrech nosím, smiø se, smiø se s ubohou! Dalibor - Ó Zdeòku mùj, ted’ chápu, proè jsi pøišel, své hry èarovným zvukem chtìls ohlásit pøíchod spasitelky mé, která má v òadrech mých tì nahradit. CD 2 1 Promìna 2. Tmavý žaláø. V pozadí zavøená branka. Dalibor døímá. Proti nìmu se vyjasní a na oblacích vznáší se Zdenìk co pøelud snu a hraje na housle. 1.výstup Dalibor. 2 Dalibor (probudí se, obraz zmizel) Nebyl to on zas? Nebyl to zas Zdenìk? Nezaslechl jsem zvuky zlat´ych strun? Kde meškáš, Zdeòku? Zjev se, pøíteli! On jde mì potìšit, ve snu se blíží, nemùže jinak ke mnì Zdenìk mùj. ó Zdeòku, jedno jen obejmutí, a žaláø bude rájem mi. Chci volnost, všecko zapomenout, zasvitne-li sem pohled tvùj! Leì hrobu stíny nás od sebe dìlí, ty trùníš tam a já zde hynu v celi. ó Zdeòku, že mi nelze obraz tvuj, kdyžv mysli mi tane, kouzlem uèarovat na vìky! ó Zdeòku, ó Zdeòku! ó kéž bych jenom housle mìl, bych aspoò tóny ty zas pøièaroval, po kterých sladce blouzním den i noc, a byt bych znal i špatnì smyìcem vládnout. Slyš! Nepraští to dveøe? Co znamená as pozdní návštéva ta? 2.výstup Dalibor, Milada. (Milada vstoupí s houslemi a lampou.) 28 4 Budivoj - Pøeslavný králi, pánové pøejasní! Tak jest, jak to pravím vám. Vzpoura, vzpoura ve mìstì vøe, podnìcována jen skrytými many, již jsou v noci èinní, by získali pro Dalibora lid. Již nìkolik jich v ruce stráže padlo. Ba již i v tento hrad, až k trùnu královského vìhlasu si zrada mrzká troufala. Slyš králi sám tohoto starce zprávu! 5 Beneš - Ètyøicet let již tomu bude, co vìrnì konám službu svou, Však nepoznal jsem nikdy jìstì co živ jsem zrádu takovou. Jakéhos mládce harfeníka jsem z útrpnosti k sobì vzal: chudým se zdál, pln nevinnosti, že byl by kámen rozplakal. Však hrùzou ztrnuly mé kosti, když pravdu zlou jsem uslyšel, že vyzvìdaè to byl a zradce, jenž s Daliborem mluvit chtìl. Dnes veèer ztratil se a zmizel, bez stopy propadnul se v zem: ten mìšec a ten list jsem našel, na kterém stojí: “Mlè a vem!” Leè nechci vìrolomnì vzíti ten mìšec - mamon proklatý! Radìj bych zhynul bídou, hlady; hrozím se této odplaty! (Wladislaw pokyne, Budivoj a Beneš odstoupí.) Povstaòte již, Milado! Vy žena jste, která pøemohla mne. Ját usmrtil vašeho bratra, chci být vám bratrem, pøítelem a vším! Sem na srdce k vìènému svazku duší! Milada - Dalibore! Dalibor - Milado! Milada - Tys ted’ mùj! Dalibor - Ano tvùj! Tvým chci býti stùj co stùj! Milada - Tvou chci býti stùj co stùj! Oba - Ó nevýslovné štìstí lásky, když duše dvì upoutá cit a v pustém, divém, života proudu v nich svornost, vìrnost nalezne byt! Nikdy nezvadne od jedu žalu, radosti vìnec rozkvítá, ano, i v noci žaláøe rozkoš rajského blaha prosvítá! Milada - Dalibore! Dalibor - Milado! Milada - Tys ted’ mùj! Dalibor - Ano, tvùj! Tvým chci býti stùj co stùj! Oba - Tys ted’ mùj! Ano, tvùj! DÌJSTVÍ TØETÍ Královská síò. Wladislaw. Kolem nìho soudcové, pøed ním Budivoj a Beneš: v rukou drží sáèek s penìzi a cedulku. PØEDEHRA 2. výstup Wladislaw, soudcové, pozdìji Budivoj. 1.výstup Wladislaw, Budivoj, Beneš, soudcové. 29 Prohlásit ortel mám? Co zde se skutkem stane, pronikne k výšinám! At Bùh nad ním rozsoudí, jak kdy to uzná sám, ont nepovstane nikdy, když v hrob jej sklátit dám. Soudcové - Nebude v zemi míru zas, dokud na rozkaz tvùj on život svùj neskonèí, dokud ještì èas! Wladislaw - Vidím, že milost slabostí by byla! Nuž staò se tak!Pøived’te správce sem! (Budivoj vstoupí) At meèem zhyne Dalibor! Soud dnešní den bud’ proveden! Leè po rytíøsku budiž ctìn! Tot káže mrav a jeho stav, by v prùvodu, by v prùvodu šel do hrobu! (Wladislaw pomalu odchází se soudci, za nimi i Budivoj.) 6 Wladislaw - V tak pozdní dobu povolal jsem vás sem, neb chvátá èin a zráda zkázou hrozí, a bez klidu a stání se òadra dmou! Ted’ znáte vše, tož rad’te! Rozhodnìte! (Sám u sebe, mezitím co se soudcové radí.) Krásný to cíl jenž panovníku kyne, když v míru jen života proud mu plyne a volnì živ je povinnostem svým! Pak mìže štìstím národ oblažiti, vavøínem skránì své si ozdobiti, pastýøem býti všude mileným! Leè, v divoké-li stran a šikù zlobì se pomstou musí zasvìtiti dobì na ústech kletbu, ortel Perunùv, ó pak se strastí život jeho zove, bez spánku noc, den hrùzy nese nové, a závidìt mu nelze korunu! (K soudcùm.) 7 Jste již u konce? Jak jste rozhodnuli? Soudcové - Že vzrùstá každé chvíle zrady moc, tož zemøi Dalibor hned dnešní noc! Wladislaw - Uvážili jste ale tohoto muže dar? V nìm plane jakýs vyšší a nadpozemský žár. Já sám jsem hodlal jednou, v žaláø jej vrhaje, se smilovati nad ním zloèinu nedbaje. Soudcové - Nebude v zemi míru zas, dokud na rozkaz tvùj on život svùj neskonèí, dokud ještì èas! Wladislaw - Jaké to slovo hrozné! Promìna 1. Daliborùv žaláø jako prve. 3.výstup Dalibor. 8 Dalibor (u zamøížovaného otvoru, bez želez) Tot tøetí noc, kterou mi naznaèila; okovù prost jsa, prolomím pak snadno poslední pruty møí¢ze proøezané. (Odhodí nìkteré kusy na zem.) A ted’ - 30 Tam møíž je prolomena! Dalibor - Ba, tak jest! Ojednu chvíli zpozdit jste se mìli a orel pyšný byl by uletìl, ve volném vzduchu perutìmi zavál, až by byl zachvìl hradu sínìmi. Budivoj - Zde zrada kráèela! Žaláøe strážce! Dalibor - Rytíøské slovo mìjte! Ont bez viny. Zde poskytnul mi housle, více nic, a tìmi jsem si krátil dlouhý èas. Budivoj - Tak jest. - O že jsem zde jej nechal dlít! Ted’ hoch ten, zrádce, unik’ pomstì mé! Dalibor - Že prch’ probùh, co díš!? Mé diky za tu zvìst! Ba tak, to byl ten mládec, který mne spasit chtìl! Ojaké kouzlo cítím, že štastnì uletìl. Když Zdenìk bídnì skonal, byl on mùj vìrný druh. A k nìmu jen mì viže pøatelství vìrný kruh. Uvìrného mi lidu jej nezastihne váš hnìv, bud’ pozdraven, mùj bratøe, a pomstou splat mou krev! Budivoj - Nejásej! Radosti se neoddej! Poselství vážné nesu ti od krále. Vyslyš je jako muž. Král takto káže: At meèem zhyne Dalibor! Soud dnešní den bud’ proveden, leè po rytíøsku budiž etén. Pro Bùh! Mnì volnost kyne! Ha, kým to kouzlem, ó svobodo, mi pláš, planoucí svìty pøede mnou otvíráš! Života proude, ted’ bujnì tìlem teè, k novému èinu pozvednu ostr´y meè! Však ted’ se zachvìj, ty Praho zpyšnìlá, která’s mi bratra pekelnì zhubila! Již zanedlouho tvou branou pùjdu dál ve jménu pomsty, kterou jsem pøísahal. Nemysli sobì, ty tam na trùnì svém, že zastavíš mne v tom hnìvu zuøivém! Já jako bouøe v hrùze se pøivalím, všeliký odpor do prachu povalím! Ha... Ted’ znamení jen houslemi bud’ dáno, pak sepnu provaz, zavìsím, a pryè! (Chopí se houslí a p¢ristoupí k otvoru ve zdi.Jakmile p¢rilo¢zí smy¢cec, praskne struna.) Ha, ký to d’as! Na houslích struna praskla. Má býti snad to špatným znamením? (V téže chvíli vrazí Budivoj se zbrojnoši.) 4. výstup Budivoj, Dalibor, zbrojnoši. 9 Budivoj - Ó nebe! Bez okovù? Ha, co vidím! 31 Smrt duši nepoleká, já znám ji z bitev. Zdenìk na mne èeká! Krev smyje vše, èím jsem se provinil! 10 Pochod Tot káže mrav a jeho stav, by v prùvodu šel do hrobu! Dalibor - Tak náhle! Právì ted’! Jak to? Proè to? Budivoj - Neptej se proè! Již nelze odvolat ten ortel smrti. Marnét vše doufáni, a marný je odpor všech p¢rátel tvých! Dalibor - Jaká to zmìna! Pøed chvílí tou svìt byl mi kouzlem, rozkoší, a nyní kryje jej èerné roucho, jak hrobu stín zahaliv jej v noc. Budivoj - Èeká již knìz, by pøipravil tì k smrti. Dalibor - Nuž bud’ si tak! Jsem pøipraven již k hrobu! Aè vidìli jste blednout líc v tu dobu, vrací se vzdor zas, jenž se hrobu lek’. Ját cítím, osud mùj že padnout káže. Již víra v osud pevnou vùli váže: Však chei co muž padnouti jako rek! Aè zasmušen je život mùj, již z mládí ját uvyk’ bouøi, která reka svádí, a spokojenì zøím na život zpìt. Ont poskytnul mi darù, jakých nebe udílí tìm, které jed pekla vstøebe, ont dal mi pøátelství a lásky kvìt! Již pøijdu, Zdeòku, a ve krátké dobì i Milada se vrátí zpìt k tobì, ta dívka svatá, pro kterou jsem žil. nuž dál, jen dál! Promìna 2. Pøed vìží. Noc. 5.výstup Jitka, Vítek a zbrojnoši Daliborovi. Milada v ženském odìvu. Lid. 11 Milada - Nezaslechli jste ještì houslí zvuky? Sbor - Tichá je noc a nìmá jako hrob. Milada - Já nedoèkám se chvíle, až jej k srdci pøivinu a po pøestálé strasti u nìho odpoèinu. Jitka - Utiš se, drahá duše, již vzejde hvìzda skvìlá a po celý pak život ti záøit bude s èela. Milada - Dosud je tich! Což nic se nepohnulo? Sbor - Tichá je noc a nìmá jako hrob. Milada - Ach, jestli snad jej stihla osudu ruka mstivá! Noc zloèinu je rouchem a ruka zrády živá! Jitka - Zapud’ ty chmury z duše, noc jasná kolem leží, tat útoèištìm lásky a chotì tvého støeží! (Zazní umíráèek.) Milada - Ha, k´y to hlahol zvonù!? Jitka, Sbor - Tiše! Slyš! Sbor mnichù (na hradì) - Život je pouh´y klam a mam a plevel tìla krása. 32 posvátný mùj klenote! Zùstaò, zùstaò pøi mnì! Neopust mne, ty mùj drahý živote! Zùstaò u mne! Milada - Dalibor! Dalibor - Ó zùstaò! Milada - Dalibor! (Zemøe.) Dalibor - Milado! (klesne nad mrtvolou.) Jitka, ženy - Hle, ta rajská Vesny rùže! Mráz zachvátil její puk. Ach, to srdce vøelé lásky, navždy umlk’ jeho tluk! Kdož dospìli až k šedinám, tìm vìèná kyne spása. Milada - Ha, on je prozrazen! (Jednomu ze zbrojnošù vyrve meè.) Vzhùru!Pojd’me! (K Vítkovi a k zbrojnošùm.) Ve zbraò, ve zbraò, vy muži! Smrt heslem naším bud’! Na hradby se návalem žeòte! Dobyjte tu skalnatou hrud’! Byt byla bych jen žena, v tìle chrabrou duši mám. Tam vítìzství nám kyne. Za mnou, za mnou, volám! Vítek, zbrojnoši - Hurá! Hurá! Hurá! Ženi - Jako Ivi se v pøíval boje pomsty laèní reci valí, zdali je ten proud - ó bìda rouchem smrti nezahalí? Z hradu bran se voje øítí, v hrozném boji meèe zvoní! Jak se skonèí as ten zápas, kam se vítìzství tu skloní? Jitka - Milada tam! Ji vede Dalibor! 7.výstup Pøedešlí. Budivoj a zbrojnoši. 13 Budivoj - Nepøátel zástup poražen a zbit. Již volnost dejte davu plachých žen. My zvítìzili! Zbrojnoši - My jsme vítìzi! Budivoj (uvidí Dalibora) Co vidím? Poddej se, Dalibore! Dalibor - Pøicházíte mi vítaní. Sladké ted’ bude mé skonání! Èeká mne Zdenìk s Miladou! (Vrhne se s Budivojem do boje a klesne.) 6.výstup Pøedešlí, Dalibor, Milada. 12 Dalibor (pøivádí ranìnou Miladu) - Milado! Milada (jako ve snu) - Kde jsem to? O jak blaze mi! Již tìla tìžká schránka volní duši mou. Na lehkých mráèkách povznáším se již vzhùru a líbám krásné, zlaté hvìzdy! A tam, a tam, jde on, Dalibor! Dalibor - Neopust mne, drahá duše, 33 ATTO I Cortile del castello, occupato da guardie. Sullo sfondo, il trono reale. Folla di popolo, tra cui Jitka. ACT ONE A courtyard of the Royal castle, occupied by guards. In the background, the royal throne. People, among them Jitka. Ouverture Overture Scena 1 Popolo, Jitka. Scene 1 People, Jitka. 1 Popolo - Oggi la sentenza verrà proclamata ed il colpevole alla giustizia consegnato! Dalibor! Dalibor! Ma, sebbene colpevole di una grave colpa, un valoroso eroe, e glorioso, lui era un tempo. Dalibor! Dalibor! 2 Jitka - (in disparte, persa nei suoi pensieri) Piccola orfanella abbandonata, tra vecchie rovine mi ha trovata, m’accolse e sotto la sua protezione la mia vita divenne uno splendido sogno. Uno sposo voleva portarmi, che fosse il più grande tesoro della mia anima, e farmi conoscere la gioia più grande: una casa mia con un caro marito. Ed ora, ed ora, ahimè! Cade nelle mani dei nemici, e presto, forse, ahimè! la notte nella tomba lo accoglierà. Popolo - Oggi la sentenza verrà proclamata ed il colpevole alla giustizia consegnato! Dalibor! Dalibor! Jitka - Ma forse no! Ma forse no! Dalla prigione lo libererò! Volo, volo sulle ali del vento, lontano. i suoi amici si uniscono a me, insieme lo libereremo, 1 People - Today the judgement will be passed and the culprit will fall into the hands of the law! Dalibor! Dalibor! But, although guilty of a serious crime, he once was a valiant hero, a glorious one. Dalibor! Dalibor! 2 Jitka - (stands immersed in thought) A little orphan, abandoned, he found me among some ancient ruins, took me under his protection, my life became a beautiful dream. He wanted to find me a husband, someone to treasure in my heart, and to make me savour the greatest of joys: my own home with a beloved spouse. And now, and now, alas! He’s fallen into the hands of the enemy, and soon, perhaps, alas! a dark tomb will receive him. People - Today the judgement will be passed and the culprit will fall into the hands of the law! Dalibor! Dalibor! Jitka - Oh no! Oh no! I must free him from prison! On the wings of the wind I must speed! His friends will join me together we shall free him, 34 lo libereremo dalle pietre sepolcrali! (Trombe suonano dietro la scena, annunciando l’arrivo del re e dei giudici). Marcia. we shall free him from the sepulchral stones! (Trumpets behind the stage announce the entrance of the King and of the Judges). March. 3 Scena 2 Gli stessi. Il re Wladislaw. (Le guardie ristabiliscono l’ordine. Il re sale sul trono. I giudici prendono posto al suo fianco). 3 Scene 2 The above. King Wladislaw. (The guards restore order. The King climbs to the throne. The judges take place at his side). 4 Wladislaw - Voi già sapete come questo bel regno sia rimasto vittima di passioni sfrenate, e da quanto tempo Dalibor si ostini a turbare quella pace che ho tanto cercato, ed ora ha commesso un nuovo crimine. Coi suoi uomini ha assalito il castello di Ploskovice, distrutto le mura, uccisone il signore. Ma ora, finalmente, è stato sconfitto dall’esercito, l’esercito che io ho mandato, spronato da Milada, che dell’ucciso è la sorella. Dopo una sanguinosa battaglia, Dalibor si è arreso. Egli ora è in mio potere, lo giudicherà il re! Ma, perché il vostro verdetto sia giusto, prima di Dalibor ascoltate Milada! 4 Wladislaw - You know that this beautiful kingdom has been the theatre of wild passions, and that Dalibor has persevered in disturbing the peace which I’ve long been seeking, and once again he’s committed a crime. With his men he assaulted the castle of Ploskovice, wrought destruction, murdered the burgrave. At last he was defeated by the army which I sent at the request of Milada, the late burgrave’s sister. After a fierce battle Dalibor was finally made to surrender. Now he is in my power, awaiting his King’s judgement! But, that your verdict may be truly fair, hear the tale of Milada, before you hear Dalibor’s! Scena 3 Gli stessi. Milada. Scene 3 The above, Milada. 5 Wladislaw - A voi la parola, raccontateci; qui è riunito il consiglio dei giudici per rendervi giustizia. Milada - Il mio animo è atterrito, oppresso è il mio cuore, quel che vi dico è il pianto, il pianto per una perdita crudele. Popolo - Con le lacrime spegne la sua rabbia! 5 Wladislaw - Tell us, tell us your tale! the Council of Judges is here reunited to do justice. Milada - My soul is aghast, my heart heaves a sigh, all I can say is that I mourn and cry over my painful loss. People - With bitter tears she quenches her anger! 35 Jitka - (tra sé) La paura mi fa rabbrividire! Milada - (raccogliendo le sue forze) Ascoltatemi! Ascoltatemi! Oh, abbiate pietà, ascoltate il pianto afflitto! Pietà! Misericordia! 6 Ormai il giorno era spento, ed il castello riposava nel sonno. Nessuno sospettava del tradimento che si stava preparando sotto le mura. Ed ecco, d’improvviso, dei colpi terribili ho udito, là, dalle foreste vicine, fui scossa dal sonno da molte grida: Dalibor! Dalibor! Cozzavano le spade in quella battaglia di sangue lontano, vicino. Nel fuoco e nel fumo le truppe lottavano già, là sotto le mura. Vagai laggiù e, ai piedi del castello, chiamai il mio caro fratello, lo vidi da lontano, barcollava, sorretto dal paggio fedele. Da una ferita aperta, terribile sgorgava il sangue dalle vene vermiglie, schiuse la bocca, si accasciò, esanime, cadde. In lacrime, il paggio fedele con sé mi portò per la foresta vicina, così per sentieri segreti sfuggii ai nostri nemici. Ed ora qui davanti a voi chino la testa. Io, di tutto derubata lo accuso, è colpevole di un delitto, poiché per vendicarsi mi ha distrutta. Dalibor! Dalibor! Jitka - (to herself) I am trembling with fear! Milada - (with all her power) Hear me out! Hear me out! Oh, have mercy, hear my sad tale! Have mercy! 6 The day was over and the castle lay in slumber. No one suspected the treason which was being prepared beneath the walls. Then, suddenly, I heard terrible blows approaching from the nearby forest, I was awaken by wild shouting: Dalibor! Dalibor! Swords clashed in bloody fighting near and far. Wrapped in fire and smoke already the troops were under the walls. I wandered in that direction and called my beloved brother, I saw him, he was staggering, supported by his faithful page. From a gaping, frightful wound his blood was gushing out of the purple veins, his lips parted, he collapsed and died. In tears, the faithful page led me to the nearby forest, and thus by secret paths I escaped from my enemies. And now, here, before you, I bow my head. I, who was robbed of everything I had, accuse him, he is guilty, through his revenge he ruined me. Dalibor! Dalibor! 36 Popolo - Che pena questa creatura! Jitka - (tra sè) La paura mi fa rabbrividire! Wladislaw - Rallegratevi, o Milada, chi vi ha ferita è mio prigioniero. Il Signore ha benedetto il mio esercito e con esso voi, e questa terra. Che entri ora Dalibor e confessi! Milada - Devo forse vederlo? L’assassino del mio caro fratello, il sangue dentro mi ribolle! Jitka - Oh, Signore, stammi ora vicino e salva la mia anima! Non posso svelare la voce del mio cuore! Milada - Il sangue dentro mi ribolle! Devo forse vederlo? L’assassino del mio caro fratello! People - Poor creature, she arouses pity! Jitka - (to herself) I am trembling with fear! Wladislaw - Rejoice, Milada, The man who hurt you is in my power. The Lord has blessed my army, and through them you, and our country. Let now Dalibor in, that he may confess his crimes! Milada - Shall I now see him? The murderer of my dear brother, My blood boils in the veins! Jitka - Oh Lord, stand by me and save my soul! I must not reveal the feelings of my heart! Milada - My blood boils in the veins! Shall I now see him? The murderer of my dear brother! Scena 4 Gli stessi. Dalibor. (Dalibor entra, con le mani legate, e si avvicina, silenzioso ma fiero, al trono del re.) Scene 4 The above, Dalibor. (Dalibor enters, with his hands in shackles, and he approaches calmly and proudly the King’s throne). 7 Milada - (stupita nel vederlo) Quale visione! I miei occhi non potevano immaginare. Popolo - (tra di loro) Per grande che sia la sua colpa, lui guarda sereno il suo destino. Wladislaw - Rispondi a questa accusa! Hai assalito il castello di Ploskovice, l’hai distrutto, il suo signore assassinato. Scagionati se puoi, subito, dinanzi a noi! 8 Dalibor - Non voglio negare, non è mio uso mentire. Giurai vendetta, e da uomo d’onore la compii. 7 Milada - (with surprise) What a sight! I would have never imagined. People - (to each other) His crime may be great but he bears his Fate fearlessly. Wladislaw - Answer your accusers! You attacked the castle of Ploskovice, destroyed it, murdered the burgrave. Deny it if you can, here, before us! 8 Dalibor - I won’t deny it, I am not accustomed to lying. I swore revenge, and, as honour bids, I took it. 37 Alla seduzione delle donne ho sempre resistito un vero amico è quel che ho più desiderato. Poi il mio desiderio si esaudì, il sogno dell’amicizia si avverò, e trovai un amico in Zdenì k. Quando il mio Zdenì k, in estasi sacra, suonava con fervore la sua musica celeste, ogni malinconia era scacciata dal mio animo e mi elevavo lassù, dove brillano le stelle più luminose. Ma ascolta! Da lungo tempo ormai ero in contrasto coi superbi consiglieri di Litomerice e andai a combatterli ancora una volta, Zdenì k al mio fianco, il mio inseparabile amico! La battaglia infuriava, il nemico catturò il mio Zdenì k, con odio crudele gli mozzò la testa, e per la mia umiliazione la issò su di un palo sopra le mura. Quale orrenda visione dovetti sopportare, rabbrividisco ancora dall’orrore! Le lacrime amare furono inutili, non riuscirono a sedare il mio dolore! Milada - Questa accusa trafigge il mio cuore! Dalibor - Allora giurai vendetta, una terribile vendetta! Ploskovice aveva aiutato Litomerice, perciò vi ho appiccato il fuoco. Ecco, era la fiaccola del sepolcro di Zdenì k! E il signore di quel castello ha pagato col suo sangue per la testa di Zdenì k! 9 Wladislaw - Con un delitto, dunque, aiutasti te stesso! Dalibor - Un uomo non rinuncia a questo diritto! Wladislaw - Ti sei ribellato al tuo re! Dalibor - Occhio per occhio, è la legge del mondo! Io qui dichiaro che se non morirò, I have never yielded to female charms, a friend was my heart’s only desire. Then my wish was fulfilled, my dream of friendship came true and I found a good friend in Zdenì k. When my Zdenì k, in sacred ecstasy, played his sweet music, all sadness was chased from my heart and I felt uplifted to the high regions of heaven where shine the brightest stars. But hear me out! For a long time I had been in quarrel with the haughty counsellors of Litomerice and once more I went to fight them, with Zdenì k at my side, my inseparable friend! The battle raged, the enemy captured my Zdenì k cruelly severed his head and, to disgrace me, hoisted it on a pole above the walls. What a dreadful sight I had to behold, I still shudder with horror! No amount of bitter tears Could soothe my pain! Milada - This accusation pierces my heart! Dalibor - Then I swore revenge, a terrible revenge! For helping Litomerice I set fire to Ploskovice, it was a torch for Zdenì k’s grave! And the burgrave paid with his blood for Zdenì k’s head! 9 Wladislaw - With a crime, then, you’ve helped yourself! Dalibor - A man cannot surrender that right! Wladislaw - You have revolted against your King! Dalibor - An eye for an eye, it’s the law of the world! I hereby declare that, if I save my life, 38 altri ancora pagheranno per la vita di Zdenì k. E se tu, o re, me lo vorrai impedire, così sicuro, sul trono, non potrai più sedere! Milada - Cosa dice? Popolo - Con queste parole ha alzato la spada su sé stesso! Giudici - Hai formulato contro te stesso una sentenza di morte! Dalibor - La vita non ha più significato da quando il mio Zdenì k è morto, non ho paura di morire, che io muoia domani, oppure anche quest’oggi! Milada - Cosa dice? Cosa dice? Dalibor - Fino al fondo si è svuotato il calice della gioia, dalle labbra ho già allontanato quella coppa illusoria! 10 Un giudice - Ecco dunque, Dalibor, la sentenza unanime: soffrirai in una cella oscura, fino alla morte! Popolo - Il volto del sole non potrà più vedere, il perdono non sfiora più il suo viso! Dalibor - Hai sentito, amico, lassù in cielo? Mi preparano la strada che porta a te, già mi sento elevare su in alto! Già ti vedo tra le nuvole, già sento la tua voce! Già m’immergo di nuovo nei suoni magici delle tue corde! La tua canzone, lassù, risuona con più gloria che quaggiù. Popolo - Che uomo! Che uomo! Dalibor - Portatemi, dunque, nel buio e nello strazio della prigione, per questa strada io corro su in cielo! (esce) Popolo - Che uomo! Che uomo! Un valoroso eroe, e glorioso, lui era un tempo. more people will die for Zdenì k’s head! And if you, my King, will try to stop me, you will not sit on your throne without fear! Milada - What is he saying? People - By those words he’s raised the sword upon himself! Judges - You have pronounced a death sentence against yourself! Dalibor - Life has no more meaning after the death of my Zdenì k, I’m not afraid to die, I can die tomorrow, for all I care, or even today! Milada - What is he saying? What is he saying? Dalibor - The cup of joy has been emptied of its last drop, my lips won’t touch any more that deceptive chalice! 10 A judge - Hear, then, Dalibor, our unanimous verdict: waste away in a cell’s darkness till death comes to take you! People - He will no longer feel the warmth of the sun, For him there can be no mercy! Dalibor - Did you hear that, friend, up there in heaven? I’m already walking on the path that leads to you, I already feel that I am floating up! I see you among the clouds, I hear your voice! Once again I savour the charming tunes of your strings! Your melody, up in heaven, sounds more glorious than on earth. People - What a man! What a man! Dalibor - Take me, then, to my dark and gruelling prison, it is the path that leads to heaven! (he leaves) People - What a man! What a man! Once he was a valiant hero, a glorious one. 39 Scena 5 Milada, Jitka, Wladislaw, i giudici, popolo. Scene 5 Milada, Jitka, Wladislaw, the Judges, people. 11 Milada - (non riuscendo più a dominarsi, si avvicina al re e ai giudici) Mi getto ai vostri piedi! Perdonatelo, come io stessa ho fatto! Quegli occhi possono fare solo il bene, dategli libertà, vogliatelo perdonare! Giudici - Ha osato minacciare il suo re, e questa la dovrà pagare cara! Milada - Ai vostri piedi io mi getto! Quegli occhi possono fare solo il bene, perdonatelo, come io stessa ho fatto! Dategli libertà, vogliatelo perdonare! Giudici - Ha osato minacciare il suo re, e questa la dovrà pagare cara! Milada - Grazia, grazia, dategli la libertà, perdonatelo, come io stessa ho fatto! Wladislaw - La legge e l’ordine devono regnare, il paese ha dovuto soffrire già troppe pene. Il dovere e la legge impongono di non dare ascolto al cuore. Il crimine dev’essere lavato attraverso la punizione. (Escono tutti, eccetto Jitka e Milada). 11 Milada - (unable to restrain her emotion any longer, she approaches the King and the Judges) I kneel down before you! Pardon him, as I myself have done! His eyes are the eyes of a righteous man, forgive him, let him go free! The Judges - He dared threaten his King, for that he must pay dearly! Milada - I kneel down before you! His eyes are the eyes of a righteous man, Pardon him, as I myself have done! forgive him, let him go free! The judges - He dared threaten his King, for that he must pay dearly! Milada - Have mercy, let him go free, Pardon him, as I myself have done! Wladislaw - Law and order must prevail, our country has suffered too many afflictions. Our duty and the law recommend not listen to our heart. Crime must be extinguished through punishment and conviction. (Everybody leaves, except Jitka and Milada). Scena 6 Milada, Jitka. Scene 6 Milada, Jitka 12 Milada - (senza notare Jitka) Quale tempesta mi riempie il cuore il sangue nelle vene non riesce a fluire! Lui ha ucciso il mio caro fratello, eppure, qualcosa mi attira a lui. Oh, non odiarmi, oh, non odiarmi, fratello! E’ per mia causa che è perduto per sempre! 12 Milada - (without noticing Jitka) What storm is raging in my heart, freezing the blood in my veins! He murdered my dear brother, and yet something in him attracts me. Oh, don’t disapprove of me, my brother! It is my fault that he is lost forever! 40 Per colpa mia, lui deve morire in una prigione, nelle torture del corpo, per colpa mia deve morire! Jitka - Questo è l’amore! L’amore ti saprà consigliare, comincia subito ad agire! Milada - Chi sei? Jitka - Di più ti dirò un’altra volta! Milada - Che cosa vuoi? Jitka - Ringraziarti con un gesto! Dalla prigione lo libereremo, volo sulle ali del vento, lontano. Milada - E dalla tomba della prigione lo libereremo, volo, volo sulle ali del vento, lontano! Milada, Jitka - I suoi amici si uniscono a me, insieme lo libereremo, lo libereremo dalle pietre sepolcrali! It is my fault that he must perish in jail, suffering torture, because of me he must now perish! Jitka - That is love! Love will advise you, you must act at once! Milada - Who are you? Jitka - I will tell you more some other time! Milada - What is it that you want? Jitka - Show you my gratitude with deeds! We shall free him from the darkness of prison, on the wings of the wind I must speed! Milada - We shall free him from the darkness of prison, On the wings of the wind I must speed! Milada / Jitka - His friends will join me together we shall free him, we shall free him from the sepulchral stones! ATTO II Una strada periferica della città e una taverna. ACT TWO A road in the lower town with an inn. Scena 1 Mercenari, poi Jitka e Vítek. Scene 1 Mercenaries, then Jitka and Vítek 13 Mercenari - Sì, è il più allegro dei mondi, questo, quando vagabondiamo da un regno all’altro, tralala, tralala... e chi si rompe il cranio ben gli sta, se lo incide bene nella memoria, tralala, tralala... (i mercenari entrano nella taverna) 14 Jitka - (entrando mentre cantano) Da questa canzone li riconosco sempre. (Vítek esce dalla taverna) 13 Mercenaries - Yes, this is a merry world when we wander from one country to the other tralala, tralala… and those of us who get crippled will know better next time, tralala, tralala… (the mercenaries enter the inn) 14 Jitka - (appearing as they are singing) By this song I always know it’s them. (Vítek comes out of the inn) 41 Sei qui, finalmente! Vítek- Jitka, bambina mia! Non rimproverarmi, tesoro mio, di tornare a casa tardi questa sera. Ho il mio esercito, ora, che non teme né tuoni né lampi! Jitka - (indicando un altro lato della città) Perché, amore mio, non sei venuto subito dalla vecchietta che mi ha dato riparo? Vítek- Stavo avviandomi per venire proprio adesso, ma sei arrivata tu da me, tesoro mio! Jitka - Vítek - (guardandosi con amore) Quest’anima, questo desiderio, questo cuore, questo mistero, sono i grandi doni del mio amore... Non lo cambierei per tutto l’oro del mondo! 15 Jitka - Conosci la sorte di Dalibor? Vítek - La gente non parla d’altro! Jitka - Allora senti questo! Dio ha riscaldato il cuore della sua accusatrice, piange adesso il suo gesto, e arde d’amore! Con la lira in mano, travestita da mendicante, è entrata di nascosto nel castello del re, ingannando il guardiano con fare lusinghiero. Ora passeggia fra le guardie, suona per loro, cerca e spia qua e là, e, con cautela, chiede di lui! Jitka, Vítek- Ora passeggia fra le guardie, suona per loro, cerca e spia qua e là, e, con cautela, chiede di lui! Jitka - Appena ci dà il segnale… Vítek- stanotte stessa… Jitka - passiamo all’azione… Vítek- e andiamo ad aiutarla! Here you are, at last! Vítek - Jikta, my child! Don’t reproach me, my jewel, for coming home late tonight. I have put together an army, gallant men who fear neither the devil nor hell! Jikta - (pointing to the other side of the town) Why, my love, haven’t you come at once to the old lady who’s given me shelter? Vítek - I was about to go, I was on my way, but you yourself have come, my jewel! Jikta / Vítek - (to each other with love) My soul, my yearning, my heart, my desire, these are the great gifts of love I would not trade them for all the gold in the world! 15 Jitka - Have you heard of Dalibor’s fate? Vítek - People speak of nothing else! Jitka - Then hear more about it! God has warmed up his accuser’s heart, now she weeps over her doing and burns with love! A lute in her hands, dressed as a beggar man, she’s managed to slip into the royal castle deceiving the guard with artful flattery. Now she’s free to wander around, entertaining them with her music, searching and prying, and cautiously asking about him! Jikta / Vítek - Now she’s free to wander around, entertaining them with her music, searching and prying, and cautiously asking about him! Jitka - But as soon as she gives us the signal… Vítek - before dawn… Jitka - we’ll get into action… Vítek - and rush to her help! 42 Jitka - Appena ci dà il segnale stanotte stessa passiamo all’azione e andiamo ad aiutarla! Jikta / Vítek - As soon as she gives us the signal before dawn we’ll get into action and rush to her help! Scena 2 Mercenari. Jitka, Vítek Scene 2 Mercenaries. Jitka, Vítek. 16 Mercenari - Sì, è il più allegro dei mondi, questo, quando vagabondiamo da un regno all’altro. (escono dalla taverna, ridendo) Vítek- Avvicinatevi, compagni, e salutate Jitka, col suo aiuto ci avviciniamo al traguardo! Mercenari - Gloria a te, gloria a te, bella fidanzata di Vítek, sulla quale, come su una fresca rosa, lo sguardo si posa con piacere! Jitka - Gloria a voi, gloria a voi, uomini d’armi, fedeli alla bandiera, sui quali, come sulle querce del bosco, lo sguardo si posa con piacere! Vítek, Mercenari - Gloria a te! Gloria a te! Or dunque, in questo felice momento, eccoci qui riuniti di nuovo, un gruppo fedele alla stessa causa, pieno di entusiasmo. Oh, cielo, accordaci il successo, anche se il fallimento incombe. Dobbiamo essere valorosi, coraggiosi così saluteremo la vittoria! Vítek - Adesso accompagno Jitka verso casa, voi restate qui a bere fino a notte, non svelate i nostri piani, mangiate, bevete, state allegri, cantate, ridete a crepapelle! (esce con Jitka) Mercenari - Guardateli mentre se ne vanno, 16 Mercenaries - Yes, this is a merry world when we wander from one country to the other. (they emerge from the inn, laughing) Vítek - Come here, comrades, and greet Jitka, thanks to her plan we’re nearing our goal! Mercenaries - Hail to you, hail to you, Vítek’s beautiful sweetheart, as pleasant a sight as a fresh rosebud! Jikta - Hail to you, hail to you, men of the sword, true to your colours, as pleasant a sight as the strong forest oaks! Vítek / Mercenaries - Hail to you! Hail to you! So in this happy hour, we are together once again, a faithful and courageous group burning with enthusiasm for our cause. Oh, heaven, grant us success, even though misfortune is threatening. We must be brave, we must be brave, and victory we shall achieve! Vítek - Now I’ll walk with Jitka towards home, you go on drinking till nightfall, do not reveal our plans, eat, drink, be merry, have fun, have a good time! (he leaves with Jitka) Mercenaries - Look at them walk away, 43 Sono una bella coppia! Alla loro salute alzate i calici, svuotiamo le botti, svuotiamo le botti! (Ritornano nella taverna). They make a fine couple! Let’s raise our cup to their health, let’s empty the barrels, empty the barrels! (They go back inside the inn). Cambio di scena I Interno del castello con alloggio di Beneš. In fondo, pattuglia di guardie. Change of stage I Inside the castle, living quarters of Beneš. In the background, guards. Scena 1 Budivoj, Beneš. Scene 1 Budivoj, Beneš. 17 Budivoj - Occorre una forte vigilanza, perché gli uomini di Dalibor sono numerosi, e se si trascura qualcosa di importante la morte dalle cento mani ci coglierà! Beneš - Signore, fidatevi di me, sarò fedele al mio giuramento! (nel mentre passa Milada, in abiti maschili, con un sacco e un cesto di viveri. Entra nell’alloggio) Budivoj - Chi è quel ragazzo che vedo passare? Beneš - Non temete, signore, ora vi dirò. Quel ragazzo è un povero mendicante, che con la sua lira melodiosa e con i canti della sua giovane voce si è ingraziato le guardie. Non ho né moglie né figli né fratelli, e la vecchiaia mi raggela il sangue nelle vene, così ho preso con me questo ragazzo, perché mi riscaldi col suo canto. E, credetemi, signore, è un abile servitore e mi si è affezionato; scommetto che nessuno, proprio nessuno ha mai avuto un servo come il mio! Budivoj - Ma non ti adagiare troppo, vecchio, 17 Budivoj - Scrupulous vigilance is needed, because Dalibor has many supporters, and should we overlook something important death will reach us with her hundred hands! Beneš - My lord, you can rely on me, I will be true to my oath! (that very moment Milada passes by, in man’s clothes, carrying a bag and a basket with food. She goes inside the quarters) Budivoj - Who is that boy who’s just passed by? Beneš - You have nothing to fear, my lord. That boy is a poor beggar, who wandered here with his melodious lute, and with his tuneful singing has won the favour of the guards. I have no wife, children or brothers, and old age gives me the chills, therefore I took this boy in to warm me up with his songs. And trust me, my Lord, he serves me well and he’s grown fond of me; I bet that no one, in the wide world has ever had as good a servant! Budivoj - Don’t feel too much at ease, old man, 44 perché gli uomini di Dalibor sono numerosi, e se si trascura qualcosa di importante questa faccenda finirà in tragedia! (Esce, solennemente). because Dalibor has many supporters and should we overlook something important this whole affair could end in tragedy! (He leaves gravely). Scena 2 Beneš. Scene 2 Beneš. 18 Beneš - (solo) Oh, la vita di carceriere è così triste, così dura e miserevole! Le porte cigolano, le catene fanno rumore i muri gettano solo ombre grigie. Io stesso mi sento un carcerato, poiché vedo intorno a me solo miseria, e anche se il mio cuore sanguina, devo mostrarmi di pietra. 18 Beneš - (alone) Oh, a jailer’s life is so saddening, so hard, it is, so dreary! Doors squeak, chains clink, all one sees is the walls’ sombre shadows. I myself feel like a prisoner, for all I see around me is wretchedness, and even when my heart is bleeding I must pretend to have a heart of stone. Scena 3 Beneš. Milada. Scene 3 Beneš, Milada. Milada - (uscendo di corsa dall’alloggio) Tutto è pronto, sedete qui! Le salsicce abbondano, c’è carne buona, burro, pane, formaggio e birra per tutti, mangiate, bevete, servitevi di tutto! Beneš - Mi riempi di gioia, sono fiero di te! Comportati sempre correttamente, e sarò per te un padre premuroso. 19 Milada - È tutto pronto, sedete qui! Beneš - Le salsicce abbondano, Milada - (running out of the quarters) Everything’s ready, take your place here! There’s plenty of sausage, juicy meat, butter, bread, cheese and beer for everybody! Eat and drink, have as much as you want! Beneš - I am so proud of you, I am filled with joy! Continue to behave well and I shall be a kind father to you. 19 Milada - All is ready, take your place here! Beneš - There’s plenty of sausage, 45 c’è carne buona, burro, pane, formaggio e birra per tutti! Milada - Mangiate, bevete, servitevi di tutto! Beneš - Ma ho ancora un compito da fare, prima di sedermi a tavola! Milada - La notte ha già spiegato le sue ali sul cielo e sulla terra! Beneš - Anche se mi dolgono le gambe, questa cosa la devo fare. Milada - Posso forse andare io al vostro posto? Le mie giovani gambe non hanno bisogno di riposo. Beneš - (con gioia) Oh, ragazzo mio, saresti così gentile? Milada - Con piacere! Beneš - Forse non va contro le regole... Milada - Budivoj è già andato via da tempo, mi dica di che si tratta e lo farò con piacere! Beneš - Ascolta! Scendi settanta gradini, là troverai Dalibor! Milada - (celando la sua gioia) Oh, Dalibor? Beneš - Conosci quel cavaliere? Milada - L’ho intravisto solo una volta. Beneš - Mi fa pena. Spesso, disperato, mi ha chiesto un violino, per poter suonare e accorciare la sua sofferenza. Quale Ceco non ama la musica? Da giovane ho suonato il violino anch’io, e credo che fra le mie vecchie cianfrusaglie ci sia ancora. Vado a prenderlo subito. Tu glielo dovrai portare. Milada - Va bene, glielo porterò. (Beneš esce dalla guardiola). juicy meat, butter, bread, cheese and beer for everybody! Milada - Eat and drink, Have as much as you want! Beneš - There’s still a task to fulfil, before I sit down to the feast! Milada - Night has already spread its wings over the heavens and the earth! Beneš - My legs may be hurting, but I must do this. Milada - Could I not go in your stead? My young legs are not hurting. Beneš - (happily) Oh, my boy, would you? Milada - With pleasure! Beneš - Perhaps it is not against the rules… Milada - Budivoj left long ago, tell me what to do and I’ll do it with pleasure! Beneš - Listen, then! Seventy steps below, you will find Dalibor! Milada - (hiding her joy) Oh, Dalibor? Beneš - Do you know him? Milada - I caught a glimpse of him once. Beneš - I feel pity for him. In despair he begged me often for a violin, to play and thus shorten his long hours of suffering. I know no Czech who wouldn’t love music! I myself played the violin when I was young, and I believe that somewhere among my old things I still have that instrument. I’ll get it right away. You shall take it to him. Milada - All right, I will. (Beneš leaves). 46 Scena 4 Milada. Scene 4 Milada. 20 Milada - Cielo! Oh, così presto è arrivato quel momento da tempo chiesto al cielo nelle preghiere, in cui mi sarà concesso di vederlo, di parlargli! Dalla gioia immensa mi si appanna la vista, il cuore batte forte! adesso resta con me, mio Dio! Oh, cielo, cielo, ascoltami! Se puoi vedere nell’umano cuore, fa che la mia voce si elevi fino a te, oh Signore! Concedigli la libertà per mano mia! Se puoi vedere nell’umano cuore, oh, cielo, cielo, concedigli la libertà, per mano mia la ottenga! 20 Milada - Goodness! Oh, so soon has the moment arrived for which I prayed to heaven, when I shall see him, speak to him! So great is my joy that my sight grows dim, my heart throbs! Now stand by me, my God! Oh heaven, heaven, hear my plea! If you can look into my heart, let my voice reach up to you, oh Lord! Grant him to be free again through me! If you can look into my heart, oh heaven, heaven, grant him to be free again, may he regain his liberty through me! Scena 5 Milada, Beneš. (Beneš rientra). Scene 5 Milada, Beneš. (Beneš returns). 21 Beneš - Eccoti il violino! Prendi una lampada, perché sono bui gli scalini laggiù. Io chiudo il cancello alle tue spalle e ti aspetto qui! Troverai altri cancelli, chiusi con le sbarre, spingili aperti, ma fai presto! Vorrei già banchettare con i miei compagni. Tu però stai tremando! Milada - Mi riempie la gioia che sentirà il cavaliere Dalibor! Beneš e Milada - Sì, sarà felice, perché il suo sogno si avvera, la sua anima prenderà coraggio e così saprà accettare meglio il suo destino. (Escono). 21 Beneš - Here is the violin! Take a lamp, for the staircase leading down is long and dark I’ll close the gate behind you and wait for you here! You will find other gates, bolted, push each one back, and do not stay too long! I want to sit to supper with my friends. But you are trembling! Milada - I am filled with joy, the same that knight Dalibor will feel! Beneš / Milada - No doubt he will be happy, for his wish is now fulfilled, his heart will take courage and he’ll bear his fate with resignation. (They leave). 47 CD 2 CD 2 1 Cambio di scena II La prigione oscura. In fondo, un cancello sbarrato. Dalibor sonnecchia. Di fronte a lui, la luce illumina d’un tratto il fantasma di Zdenì k che suona il violino. 1 Change of stage II Dark jail. In the background, a closed gate. Dalibor is sleeping. Suddenly, the ghost of Zdenì k appears in a burst of light, playing the violin. Scena 1 Dalibor. Scene 1 Dalibor. 2 Dalibor - (la visione scompare, si sveglia) Non era forse lui? Non era di nuovo Zdenì k? Non ho udito forse il suono delle sue corde d’oro? Dove sei, Zdenì k? Mostrati a me, amico mio! Viene a consolarmi apparendomi nel sonno, non potrebbe raggiungermi in altro modo. Oh, Zdenì k, se potessi solo sfiorarti la prigione diventebbe il Paradiso. Dimenticherei tutto, persino la libertà, se potessi averti qui una sola volta! Ma le ombre sepolcrali ci dividono, tu sei su un trono, là, ed io sto morendo, qui, in una cella. Oh, Zdenì k, perché per una qualche magia non posso vedere la tua immagine per sempre! Oh, Zdenì k, oh, Zdenì k! Oh, se solo avessi qui un violino per poter ricreare quei suoni meravigliosi che giorno e notte sento nei miei sogni, potrei sopportare meglio il mio destino crudele. Ascolta! Il cancello scricchiola! Che significa una visita così tardi? 2 Dalibor - (the vision disappears and he awakes) Was that not he? Was it not Zdenì k once again? Was that not the sound of his golden strings? Where are you Zdenì k? Show yourself to me, He tries to comfort me appearing in my sleep, for there’s no other way. Oh, Zdenì k, if I could only touch you my jail would become Paradise. Everything I would resign, even freedom, to have you once visit this place! But the shadows of death keep us apart, you sit upon a throne, up there, while here, in jail, I am dying. Oh, Zdenì k, why can’t I, by some magic power, see your dear image for eternity! Oh, Zdenì k, Oh, Zdenì k! Oh if only I had a violin, I could reproduce those wondrous sounds which I hear day and night in my dreams, I would better endure my cruel fate. Hear! The gate is squeaking! What is the meaning of such a late visit? Scena 2 Dalibor, Milada. Entra Milada col violino e la lampada. Scene 2 Dalibor, Milada Enters Milada, carrying the violin and the lamp. 48 3 Milada - (handing the violin to Dalibor) Accept this gift from my hand. Dalibor - (grabs the violin without looking at Milada) Finally, the violin which I so long wished for! Oh, Zdenko, Zdenko, Zdenko! But who are you? Tell me, boy, I had not paid attention. Milada - You ask who I am? Alas, have you not seen my face before? I am that wretched woman who, for revenge, accused you and brought you before a court! It is because of me that you are dying in prison! Dalibor - Milada! Is it possible? Milada - I am Milada! Seeing you but once, in that solemn moment, was enough for me to repent, I feel bitter remorse for what I have done, as the law of the Lord commands. Disguised as a minstrel I managed to get inside the castle, without caring for my liberty or my life, and gained favour with the guard, who sent me here with the violin. But, concealed, I’m also bringing what’s needed for a flight, for breaking your fetters and regain freedom’s path! Dalibor, I beg your pardon, forgive, I beseech you, my cruel vengeance. A deep sorrow oppresses my heart, do forgive this wretch! Dalibor - Oh, dear Zdenì k, now I know why you came, 3 Milada - (dando a Dalibor il violino) Accetta questo dono dalle mie mani. Dalibor - (prende il violino dalla mano di Milada senza guardarla) Finalmente ho qui il violino che ho tanto desiderato! Oh, Zdenko, Zdenko, Zdenko! Ma, chi sei tu? Dimmelo ragazzo, non ti avevo prestato attenzione, prima. Milada - Tu mi chiedi chi sono? Ahimè, non hai mai visto il mio viso? Sono quella donna miserabile che per vendetta ti ha accusato e ti ha fatto condannare! È colpa mia se adesso stai morendo in prigione! Dalibor - Milada! E’ mai possibile? Milada - Sono Milada! Ma è bastato vederti solo una volta, in quell’attimo sacro, per sentire rimorso di quel che ho fatto, mi pento amaramente, per quell’azione, come comanda la legge del Signore! Vestita da suonatore di lira, mi sono introdotta nel castello, senza pensare alla mia vita, alla mia libertà, e mi sono fatto amico il guardiano, che mi ha mandata qui con il violino. Ma di nascosto ho portato anche ciò che servirà per farti scappare, per abbattere le sbarre e aprirti la strada della libertà! Ti prego, Dalibor, perdonami, perdonami ti prego quella vendetta feroce. Nel mio cuore porto un dolore profondo, riconciliati con questa miserabile! Dalibor - Oh, Zdenì k caro, adesso capisco perché eri venuto, 49 con quel suono meraviglioso volevi annunciare l’arrivo della mia salvatrice, che a te dovrà sostituirsi nel mio cuore! Alzatevi, Milada! Voi siete la donna che mi ha conquistato. Io ho ucciso il vostro fratello, e adesso voglio essere io vostro fratello, amico, tutto! Qui sul mio cuore, nell’eterna unione delle anime! Milada - Dalibor! Dalibor - Milada! Milada - Sei mio, adesso! Dalibor - Sì, sono tuo! Voglio esserlo, costi quel che costi! Milada - Dalibor! Voglio essere tua costi quel che costi! Milada e Dalibor - Oh, l’inesprimibile felicità d’amore, quando due anime sono unite dal sentimento, e nel mezzo di una vita desolata, pazza, trovano unione, fedeltà reciproca! Oh, l’inesprimibile felicità dell’amore, che neppure la rabbia, la tristezza affievolisce, che sboccia come un fiore della gioia, sì, anche nelle tenebre della prigione, riluce la beatitudine del Paradiso! Milada - Dalibor! Dalibor - Milada! Milada - Sei mio adesso! Dalibor - Sì, sono tuo! Voglio esserlo, costi quel che costi! Milada e Dalibor - Adesso sei mio! Sì, sono tuo! your wondrous melody was meant to herald the arrival of my saviour, of she who is to take your place in my heart! Stand up, Milada! You are the woman who has conquered me. I killed your brother, and now I want to be your brother, your friend, your everything! Here, to my heart, let our souls be joined for ever! Milada - Dalibor! Dalibor - Milada! Milada - You are mine! Dalibor - Yes, I am thine! I will be thine, come what may! Milada - Dalibor! I will be thine, come what may! Milada / Dalibor - Oh, unspeakable charm of love, when two souls are tied by passion and in the midst of this dreary, foolish life form a bond of reciprocal faith! Oh, unspeakable charm of love, which neither anger nor sadness can dim, which blossoms like the flower of joy, yes, even in a dark prison, the bliss of Paradise can shine. Milada - Dalibor! Dalibor - Milada! Milada - You are mine! Dalibor - Yes, I am thine! I will be thine, come what may! Milada / Dalibor - You are mine! Yes, I am thine! 50 ATTO III ACT THREE Sala reale. Wladislaw. Intorno a lui i giudici; al suo cospetto Budivoj e Beneš, quest’ultimo in ginocchio: in mano tiene un borsello pieno di denaro e un foglio. A royal chamber. Wladislaw. Around him the Judges, in front of him Budivoj and Beneš, the latter kneeling down and holding a purse and a piece of paper. Ouverture Overture Scena 1 Wladislaw, Budivoj, Beneš, i giudici. Scene 1 Wladislaw, Budivoj, Beneš, the Judges. 4 Budivoj - Nobilissimo re, illustri signori! È così come vi dico. La rivolta, la rivolta, ribolle in città, aizzata da agenti segreti, che agiscono di notte, per raccogliere gente in favore di Dalibor. Alcuni sono già nelle mani delle guardie. Persino in questo castello, vicino al trono regale, ha osato arrivare il bieco tradimento. Ascoltate voi stesso, sire, il rapporto di questo vecchio! 5 Beneš - Ormai da quarant’anni svolgo fedelmente il mio servizio ma mai, in tutta la vita, ho visto un tradimento simile. Ho preso con me per pietà un giovane suonatore di lira, sembrava povero, innocente, chi avrebbe sospettato! Ma rabbrividii di orrore quando udii la terribile verità, che era un traditore, una spia, quando voleva parlare con Dalibor. Questa notte è sparito, senza lasciar traccia, nel nulla; solo questo borsello ho trovato, 4 Budivoj - Noble King, illustrious lords! It is as I’m telling you. Revolt, revolt is brewing in town, instigated by secret agents, who act at night, gathering people in support of Dalibor. Some have already been arrested by our guards. Not even this castle, not even the King’s throne was spared by abject treason. Hear, my King, what this old guard has to say! 5 Beneš - For as many as forty years I have faithfully carried out my task but never did I see a treachery of this guise. Moved to compassion I sheltered a young minstrel, he looked so innocent and poor, who would have suspected! But I shuddered with fear when I heard the horrible truth, that he was a spy, a traitor, that he wanted to speak to Dalibor. Tonight he disappeared, he vanished without trace; I only found this purse, 51 ed una lettera su cui è scritto: “Prendi e taci!”. Ma quel borsello non voglio prenderlo sarebbe tradimento, è denaro del diavolo! Preferirei morire nella fame e nella miseria, una simile ricompensa mi fa rabbrividire! (A un cenno di Wladislaw, Budivoj e Beneš escono). and a message saying: “take this and keep silent”. But I won’t take this purse, I won’t betray, it’s the devil’s money! I’d rather linger in hunger and poverty, such a reward makes me shiver with horror. (Wladislaw beckons, Budivoj and Beneš leave). Scena 2 Wladislaw, i giudici, poi Budivoj. Scene 2 Wladislaw, the Judges, then Budivoj. 6 Wladislaw - A questa tarda ora vi ho chiamati qui, poiché urge l’azione il tradimento minaccia la nostra rovina, ed il mio animo è inquieto e senza posa. Ora sapete tutto; allora date un consiglio! Decidete! (a parte, mentre i giudici discutono) Che bellissimo traguardo, per un sovrano, quando la sua vita scorre pacifica, ed è libero di compiere il suo dovere! Così può rendere felice il suo popolo, può ornare con allori la sua fronte, ed essere amato da tutti! Ma, se deve vivere in tempi selvaggi, pronunciare giudizi sulle liti tra i suoi sudditi, e avere sulle labbra la maledizione della condanna a morte, oh, allora la sua vita può dirsi penosa, passa le notti insonne, e il giorno gli porta nuove pene, allora nessuno gli invidia la corona! (ai giudici) 7 Avete terminato? Qual è la vostra decisione? I giudici - Poiché con ogni istante che passa il tradimento prende forza, Dalibor sia messo a morte, subito, stanotte! Wladislaw - Avete, però, considerato bene 6 Wladislaw - I’ve summoned you here at this late hour because immediate action is needed, treason is threatening to strike a blow, and my soul is troubled and restless. Now you know all; advise me! reach a decision! (aside, while the Judges are consulting) What a beautiful aim for any king to achieve, to live in peace among his people and be free to attend to his duty! Then he can make his people happy, wear the laurel on his brow, and be loved by everyone! But when he lives in times of strife, when he must rule on men’s disputes and have upon his lips the curse of guilty verdict, then his life becomes miserable, at night he cannot rest, and each new day carries new pain, then no one envies his crown! (to the Judges) 7 Are you ready? What is your decision? Judges - Since with every minute the power of treason gains strength, then Dalibor must die, this very night! Wladislaw - But have you duly thought 52 le virtù di quest’uomo? Una fiamma nobile e soprannaturale arde in lui. Io stesso una volta, facendolo arrestare mi trovai a graziarlo, gli perdonai il delitto commesso. I giudici - La pace in questa terra non tornerà finché non darai l’ordine di far cessare la sua vita, questa notte stessa! Wladislaw - Quali orribili parole! Devo pronunciare la sentenza? Ciò che accade quaggiù sarà giudicato in cielo. Dio decida sul suo destino, sul dove e quando debba morire. Se pronuncerò la sentenza di morte. sarà la sua fine. I giudici - La pace in questa terra non tornerà finché non darai l’ordine di far cessare la sua vita, questa notte stessa! Wladislaw - Riconosco che la misericordia parrebbe debolezza! Che sia così! Chiamate Budivoj! (Budivoj entra) Che Dalibor muoia sotto la spada! L’esecuzione sia compiuta oggi stesso! Ma che sia trattato come si addice ad un cavaliere! Come impone l’uso ed il suo rango, che un corteo lo accompagni fin nella tomba! (Wladislaw e i giudici escono lentamente, seguiti da Budivoj). of this man’s virtues? The flame that burns in him is noble, supernatural. I myself, once, intended sending him to jail, but pardoned him his crime. Judges - Peace will not reign on this kingdom till you give the order that he be killed this very night. Wladislaw - What dreadful words! Am I to sentence him to death? What is decided on earth will be judged in heaven. Let God decide his destiny, when and where he must die. If I pronounce his death sentence it will be the end of him. Judges - Peace will not reign on this kingdom till you give the order that he be killed this very night. Wladislaw - I see how pity can look like weakness! So let it be! Let Budivoj enter! (Budivoj enters) Dalibor be killed by the sword! Right now, today! But let him be treated like the knight he is! As befits tradition and his standing, he must be escorted he must be escorted to his grave! (Wladislaw and the Judges slowly depart, followed by Budivoj). 53 Cambio di scena I Di nuovo la prigione di Dalibor. Change of stage I Dalibor’s cell. Scena 3 Dalibor. Scene 3 Dalibor. 8 Dalibor - (vicino alla finestra con inferriata, senza catene) È giunta la terza notte, quella di cui lei mi ha parlato; spezzate le catene, rompo le ultime sbarre con facilità, poiché sono già mezze segate. (fa cadere alcune sbarre) E adesso... Oh Dio, la libertà! oh, libertà, mi ardi dinanzi, e mondi splendenti apri ai miei occhi! Il mio corpo riprende vita. Sono pronto a nuove azioni con la spada affilata! Trema, adesso, Praga superba, che hai ucciso il mio amico così crudelmente! Fra poco varcherò le tue porte, per compiere la vendetta che ho giurato. E tu, su quel tuo trono, non credere di poter fermare la mia rabbia feroce! Come la tempesta piomberò su di voi e in polvere ridurrò ogni resistenza! Ora devo mandare un segnale col mio violino, poi fisso la corda, la getto fuori e via! (prende il suo violino, si avvicina alla finestra. Al primo colpo d’archetto, una corda si spezza) 8 Dalibor - (standing near the barred window, without shackles) It’s the third night, the one she mentioned; I broke my shackles, and I shall easily break the bars of this window, which have been partly sawn. (throws a few bars on the floor) And now… Oh God, freedom! Oh, freedom, you are here in front of me and unfold before me beautiful worlds! My body is brought back to life. I’m ready for new deeds with my well-sharpened sword! And now tremble, proud town of Prague, you who have killed my friend in such a cruel fashion! Soon I shall pass your gates to carry out the revenge that I once swore. Neither you, my King, with all your power, could stop my ferocious wrath! Like a storm I shall fall upon you and break every resistance! Now I must give the signal with my violin, then I’ll fix the rope, throw it out and flee! (he takes the violin, goes near the window. At the first strike of the bow a string breaks) 54 Che significa? Sarà forse un cattivo presagio? (A quel punto entra Budivoj, seguito dagli scudieri). What does this mean? Could it be a bad omen? (At the same time Budivoj rushes in with his men). Scena 4 Budivoj, Dalibor, soldati. Scene 4 Budivoj, Dalibor, soldiers. 9 Budivoj - Oh, cielo! E’ senza catene! Cosa vedo! Le sbarre rotte! Dalibor - Sì, è così! Se solo aveste ritardato di un istante l’aquila fiera sarebbe volata via, librandosi nell’aria, col vento delle ali avrebbe fatto tremare le sale del castello. Budivoj - Questo è tradimento! Il guardiano della prigione! Dalibor - Parola di cavaliere: lui è senza colpa. Non mi ha dato altro che questo violino, con cui spezzare il tempo troppo lungo. Budivoj - È così. Perché l’ho fatto restare così a lungo! Quel ragazzo, quel traditore, è sfuggito alla punizione! Dalibor - È sfuggito, dici? Ti ringrazio per questa notizia! Sì, era quel giovane che mi voleva salvare! Oh, che gioia provo, sapendo che è riuscito a volare via. Dopo la morte di Zdenì k, è divenuto lui il mio compagno fedele, e a lui mi lega un forte legame d’amicizia. Il mio popolo fedele lo proteggerà dalle ire del re. Ti saluto, fratello mio, con la vendetta rendi giustizia al mio sangue! Budivoj - Non esultare! Non è proprio il momento! Ti porto un grave messaggio del re. Ascoltalo da uomo. 9 Budivoj - Oh, heaven! He’s broken his shackles! What do I see! He’s broken the bars too! Dalibor - Right you are! Had you but come one minute later the proud eagle would have flown away, high in the air, it would have spread its wings and made all of the castle tremble. Budivoj - It’s the work of a traitor! The jailer! Dalibor - My word of knight: he’s innocent! He just procured this violin, with which to kill off time. Budivoj - That’s true. Why did I let him stay so long! That boy, that traitor, escaped punishment! Dalibor - He’s escaped, you say? I’m grateful for that news! Yes, it was that boy who wanted to free me. How pleased I am that he managed to escape! After Zdenì k ’s death he became my faithful friend, I’m tied to him by a strong bond of friendship. My people will protect him from the King’s wrath. Farewell, my brother, Avenge my blood! Budivoj - Do not rejoice! It is not time! I bring you a grave message from the King. Take it like a man. 55 Questa è la volontà del re: Dalibor deve morire sotto la spada! L’esecuzione sia compiuta oggi stesso, senza indugio! ma che sia trattato come si addice ad un cavaliere! Come impone l’uso ed il suo rango, che un corteo lo accompagni fin nella tomba! Dalibor - Così, all’improvviso? Oggi stesso? Perché mai? Budivoj - Non chiedermelo! Non si può appellare questa condanna a morte, inutile nutrire speranze, vana ogni resistenza, con la spada o a parole. Dalibor - Che cambiamento improvviso! Solo un attimo fa la vita mi pareva beata, leggiadra, e ora, la copre un drappo nero, che la trasforma in notte oscura, come l’ombra della tomba. Budivoj - Il prete vi attende, per prepararvi alla morte. Dalibor - Allora, che sia così! Sono pronto a morire! Anche se per un attimo mi avete visto impallidire, ora ritrovo il coraggio e la forza. Ora so che devo morire, camminerò incontro al mio destino e morirò da eroe! Non ebbi mai vita facile, mi sono abituato a destreggiarmi nelle tempeste e guardo sereno alla vita passata. La vita è stata generosa con me, mi ha colmato di quei doni, che distribuisce a coloro che soffrono, mi ha dato l’amicizia e l’amore. Hear the King’s will: Dalibor must be killed by the sword! This very day, without delay! But let him be treated like the knight he is! As befits tradition and his standing, let him be escorted to his grave! Dalibor - Right now? Without delay? What does it mean? Budivoj - Do not inquire! This death sentence cannot be altered, Any hope is in vain, any attempt to resist, by sword or by word, is useless. Dalibor - What a sudden change! A moment ago the world looked charming, radiant, and now it is wrapped in a black shroud, covered by darkness, by the shadow of death. Budivoj - The priest is waiting, to prepare you for death. Dalibor - Then be it so! I am prepared to die! Though for a moment I turned pale, courage and strength are coming back to me. I know now that I must die, I shall walk to my destiny, and I shall die like a hero! My life was never an easy one, thus I got used to brave the storms, and I look back serenely on my past. Life has been generous with me, it gave me the gifts that are set aside for those who suffer, it gave me friendship and love. 56 Arrivo, Zdenì k, e presto anche Milada si unirà a noi quella fanciulla santa, la mia vita. Allora avanti, avanti! La morte non mi spaventa, l’ho conosciuta in battaglia! Zdenì k mi sta aspettando! Il sangue lavi le colpe di cui mi sono macchiato. 10 (Marcia). I’m coming, Zdenì k, and soon also Milada shall join us that blessed girl, my life. Let’s go, let’s go! Death does not frighten me, I’ve met her in battle! Zdenì k awaits me! May my blood wash away all my errors. 10 (March). Cambio di scena II Davanti alla torre. Di notte Change of stage II In front of the tower. At night. Scena 5 Jitka, Vítek e i mercenari di Dalibor. Milada in abiti femminili. Il popolo. Scene 5 Jitka, Vítek and Dalibor’s Mercenaries. Milada in a woman’s dress. People. 11 Milada - Ancora non udite il suono del violino? Coro - Muta è la notte, e silenziosa! Milada - Non riesco più ad aspettare, vorrei stringerlo al cuore e, dopo tutte queste pene, riposare finalmente con lui. Jitka - Calmati, calmati, anima cara, spunterà presto, spunterà presto la splendida stella, che per tutta la vita illuminerà la tua fronte. Milada - Che silenzio! Nulla si muove? Coro - Muta è la notte, e silenziosa! Milada - Ah, forse la mano vendicatrice del destino lo ha raggiunto! La notte aiuta il crimine e sorregge la mano del tradimento! Jitka - Scaccia quegli orrori dal tuo animo, una notte luminosa ci avvolge, è il rifugio dell’amore e proteggerà il tuo sposo. 11 Milada - No trace yet of the signal? Chorus - Nothing yet, the night is silent! Milada - How long this waiting is, till I can hold him in my arms and, after all the suffering, rest near him. Jitka - Be patient, dear lady, your good star soon shall rise and for the rest of your life shall shine upon you. Milada - What silence! No movement yet? Chorus - Nothing yet, the night is silent! Milada - Ah, the avenging hand of destiny perhaps has struck him down! Night hides the crime and guides the traitor’s hand! Jitka - Chase from your heart such nightmares, A peaceful night like this is the lovers’ refuge, it will protect your spouse. 57 (risuona la campana a morto) Milada - Oh, perché il suono delle campane? Jitka, coro - Silenzio! Ascolta! Coro di monaci - (nel castello) La vita non è che vanità ed illusione e nulla vale la bellezza del corpo, a quelli che sono giunti alla vecchiaia, a quelli spetta la salvezza eterna! Milada - Oh, è stato scoperto! (strappa la spada a uno dei soldati) Orsù, coraggio, andiamo! (a Vítek e ai soldati) All’assalto, all’assalto, uomini! La morte sia il nostro motto! Assaliamo con forza quelle mura, conquistiamo quella fortezza! Sono una donna, ma nel mio corpo c’è un cuore impavido, ci attende la vittoria. Avanti! Avanti, andiamo! Vítek, mercenari Urrà, urrà! Coro delle donne - Come leoni si gettano nella fiumana della lotta, questi eroi assetati di vendetta, non annegheranno, ahimè in fiumi di sangue? Dalle porte del castello si precipitano le guardie, le spade cozzano nell’orrenda battaglia! Quale esito avrà questa battaglia, da che parte si schiererà la Vittoria? Jitka - Ecco Milada! Dalibor la conduce! (a death knell is heard) Milada - Oh, hear the bells! Jitka / Chorus - Hush! Listen! Chorus of monks - (in the castle) Life is but vanity and illusion, beauty is worth nothing, only those who reach an old age can dream of salvation. Milada - Oh, he’s been discovered! (she grasp the sword of one of the men) Now forward! Forward! (to Vítek and the men) To arms, to arms, my men! Let death be our war-cry! Dash against those walls, conquer the fortress! Though I am just a woman, my heart is valiant and brave, victory awaits us! Come on, come on! Forward! Vítek / Chorus of Mercenaries Hurrah! Hurrah! Women - Like wild beasts they fling themselves into fight, those heroes, thirsting for vengeance. Will they, alas, be drowned in streams of blood? The royal guards dash out of the castle, swords are crossed in savage fights! Whom will Fate favour, and who will lose the fight? Jitka - There is Milada! She’s led by Dalibor! 58 Scena 6 Gli stessi, Dalibor, Milada. Scene 6 The above, Dalibor, Milada. 12 Dalibor - (conduce Milada ferita) Milada! Milada - (come in un sogno) Dove mi trovo? Oh, come mi sento leggera! La mia anima si libera della pesantezza del corpo! Su nuvole leggere sto salendo, in alto, e bacio le splendide stelle dorate! Ed ecco, là, cammina lui, Dalibor! Dalibor - Non mi abbandonare, cara anima mia, mio tesoro prezioso! Rimani, rimani con me! non mi abbandonare, tu, cara vita mia! Rimani con me! Milada - Dalibor! Dalibor - Oh, rimani! Milada - Dalibor! (muore) Dalibor - Milada! (cade in ginocchio davanti al suo corpo) Jitka, coro delle donne Guardate questa splendida rosa primaverile! Il gelo ha bruciato i suoi boccioli! Oh da quel cuore pieno di amore il battito è sparito per sempre! 12 Dalibor - (bringing the wounded Milada) Milada! Milada - (like in a dream) Where am I? Oh, how light I feel! My soul sheds the weight of my body! On tender clouds I rise, high up, to touch the golden stars! And there, there goes he, Dalibor! Dalibor - Oh, do not leave me, my dearest soul, my only one, my wife! Oh stay, stay with me! Do not abandon me, my precious life! Stay with me! Milada - Dalibor! Dalibor - Oh, stay! Milada - Dalibor! (she dies) Dalibor - Milada! (falls to his knees by the corpse) Jitka / Women Behold this tender rosebud! Frost has burnt its petals! Her heart so full of love will no longer beat! Scena 7 Gli stessi. Budivoj e i soldati. Scene 7 The above. Budivoj and the soldiers. 13 Budivoj - La folla dei nemici è sconfitta e uccisa. Lasciate andar via queste donne impaurite. Abbiamo vinto! Soldati - Siamo i vincitori! 13 Budivoj - The enemy is beaten and dispersed. Let these frightened women go freely. Victory is ours! Soldiers - Victory is ours! 59 Budivoj - (vedendo Dalibor) Che cosa vedo qui? Arrenditi, Dalibor! Dalibor - Siete i benvenuti! Ormai sarà dolce, per me, la morte! Zdenì k e Milada mi stanno aspettando! (Si getta nella mischia con Budivoj, cade trafitto e muore). Budivoj - (seeing Dalibor) What do I see? Surrender, Dalibor! Dalibor - Welcome! You are welcome! My death shall now be sweet! Zdenì k and Milada await me! (He flings himself against Budivoj and falls dead). 60 Grateful thanks to Professor Jan Smaczny for his kind cooperation