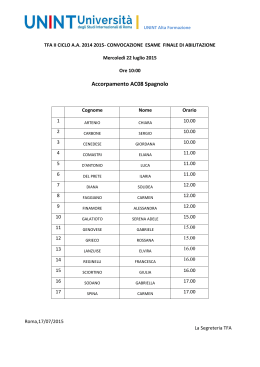

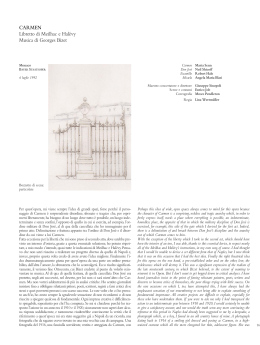

CARMEN Libretto di Henry Meilhac e Ludovic Halévy Musica di Georges Bizet Napoli TEATRO SAN CARLO 10 dicembre 1986 Carmen Don José Escamillo Micaela Frasquita Mercedes Dancaire Remendado Zuniga Morales Lillas Pastia Guida Bruja Martha Senn Luis Lima Boris Martinovich Alida Ferrarini Alessandra Rossi Francesca Franci Alfonso Antoniozzi Piero De Palma Jean Laine Giuseppe Riva Nunzia Fumo Rosario Campese Trisha Brown Maestro concertatore e direttore Maestro del coro Scene e costumi Coreografia Emil Tchakarov Giacomo Maggiore Enrico Job Trisha Brown Regia Lina Wertmüller Orchestra e coro del Teatro di San Carlo di Napoli Pueri Cantores di S. Chiara di Napoli diretti da Enrico Buondonno Carmen 132 “Questa musica di Bizet” – scriveva Friedrich Nietzsche nel maggio 1888, ne Il caso Wagner. Lettera da Torino – “mi sembra perfetta. Si avvicina con un passo leggero, agile, garbato. È gentile, non vi mette in sudore. ‘Tutto quello che è buono, è leggero, tutto quello che è divino, corre su piedi delicati’: prima tesi della mia estetica. Questa musica è perfida, raffinata, fatalista, e resta tuttavia popolare: la sua raffinatezza è quella d’una razza, non di un individuo. È ricca. È precisa. Costruisce, organizza, giunge a compimento: per questi aspetti forma un contrasto col polipo musicale, con la ‘melodia infinita’… L’opera di Bizet, anche lei è redentrice; Wagner non è l’unico ‘redentore’. Con quest’opera si prende congedo dall’umido settentrione, da tutte le brume dell’ideale wagneriano. Già l’azione ce ne sbarazza. Di Mérimée conserva ancora la logica nella passione, la linea diritta, la dura necessità; possiede anzitutto ciò che è proprio dei paesi caldi, la secchezza dell’aria, la sua limpidezza. Eccoci, in ogni senso, sotto un altro clima. Un’altra sensualità, un’altra sensibilità, un’altra serenità si esprimono qui. Questa musica è gaia; ma non d’una gaiezza francese o tedesca. La sua gaiezza è africana; la fatalità vi aleggia sopra, la sua felicità è corta, improvvisa e senza pietà… E l’amore, infine, l’amore rimesso al suo posto nella natura! Non l’amore della ‘fanciulla ideale’! Nessuna traccia di ‘Sentimentale’! Al contrario, l’amore in quel che ha d’implacabile, di fatale, di cinico, di candido, di crudele: ed è in questo ch’esso partecipa della natura! Non conosco altri casi in cui lo spirito tragico che è l’essenza dell’amore si esprima con una simile asprezza, rivesta una forma così terribile come nel grido di Don José che termina l’opera: Oui, c’est moi qui l’ai tuée./ Carmen, ma Carmen adorée. Una tale concezione dell’amore è rara: distingue un’opera d’arte fra mille... Vedete già come questa musica mi rende migliore? Bisogna mediterraneizzare la musica: ho le mie ragioni per enunciare questa formula” “Opera dolce e oscura come l’occhio della sua protagonista – quest’occhio di belva amo- “This music by Bizet”, wrote Friedrich Nietzsche in May 1888, in The Wagner Case, Letter from Turin,“seems to me to be perfect. It approaches with a light, agile, well-mannered step. It is gentle, and it does not make one sweat.‘Everything which is good is light, everything which is divine runs on delicate feet’.This is the first thesis of my aesthetics.This music is unfaithful, refined and fatalist, but it remains popular: its refined nature is that of a race, not of an individual. It is rich, it is precise. It constructs, organizes and completes. For this reason it forms a contrast with the musical octopus, with ‘infinite melody’... Bizet’s opera is also a redeemer. Wagner is not the only ‘redeemer’.This opera takes its leave of the rainy North, and of all the mists of the Wagnerian ideal. The action already gets rid of them. It maintains something of Mérimée in its passion, its linearity and its harsh necessity. Above all, it possesses the attributes of hot countries: the dryness of the air, its limpidity. Here we are in every sense in another climate.Another sensuality, another sensibility and another serenity is expressed here.This music is gay, but it is not of a French or German gaiety. Its gaiety is African. Fatality hovers above, and its happiness is brief, unexpected and pitiless... It is, in short, love, love restored to its place in nature! It is not the love of the ‘ideal girl’! There is not trace of the ‘Sentimental’! It is, on the contrary, love in what it has of the implacable, the fatal, the cynical, the innocent, the cruel, and it is in this sense that it is part of nature! I know of no other cases in which the tragic spirit which is the essence of love is expressed with similar asperity, taking on such a terrible form as in the cry of Don José with which the opera ends: Oui, c’est moi qui l’ai tuée./ Carmen, ma Carmen adorée. Such a conception of love is rare: it distinguishes one in a thousand works of art... Can you already see how this music has improved me? Music must be Mediterraneanized: I have good reason to enounce this formula” “An opera as sweet and dark as the eye of its main character - the eye of a love-struck beast which in its gaze reflects the senseless tragedy of our games... Savinio’s phrase contains a truth which strikes an immediate chord in every Carmen - Don José 13 134 rosa che nel suo cristallo riflette l’insensata tragedia dei nostri giochi… La frase di Savinio contiene una verità che trova rispondenza immediata in ognuno di noi… Come i personaggi dei nostri sogni sono sempre proiezioni di noi stessi, così è Carmen. Forse per questo il secolo, percorso da tante febbri di crescita sociale e battaglie libertarie, in fondo ha sempre teso a identificarla come il simbolo della libertà. Zingara, gitana, nomade, passionale… No, Carmen appartiene a un’altra famiglia. La sua curiosità femminile diventa libertina all’occhio francese che la guarda. Fascino, la sua anarchia. Simbolo, la sua stessa natura della libertà. Eppure il libretto geniale che Meilhac e Halévy dedussero dal romanzo di Merimée, lascia emergere un dato. Proprio la perdita della libertà di Carmen… E Carmen perde la sua libertà perché le capita un fatto nuovo e inaspettato. Lei, che non ha che avventure passeggere, lei, Carmen, si innamora… e non intende ascoltare più altra regola se non quella che le canta dentro… Lettura mediterranea nelle radici antiche di questa eroina ambigua che, bifronte e disponibile, evoca e stuzzica letture diverse, come appunto il bosco psicoanalitico dove sentieri e panorami offrono differenti misteriose e allarmanti prospettive. Carmen è più grande delle altre proprio perché la sua ambiguità suona sempre cimbali e nacchere per indicarci i ritmi delle possibilità. Carmen è insieme dissacratrice e sacerdotessa dell’amore. Per amore della vita cerca la morte come rito. È della pasta antica delle Medée e insieme è ballerina di flamenco con nacchere e fiore in bocca. Bizet ne fece un’operetta, ma mentre la componeva, la forza del rito sfondava il tessuto leggero e usciva, possente: il melodramma. È solare e notturna. Anche se l’attrazione rassicurante che esercita il dramma ha, negli anni, sempre più tradito la doppiezza di lei pian piano è diventato melodramma, fino in fondo. E Parigi? Parigi che diventa una Spagna sognata e mai vista? Altra doppiezza seducente dell’opera. È proprio questa pariginità, questo coté Operetta, quasi sempre sacrificato nelle tante e gloriose edizioni e manipolazioni di Carmen, che invece ho cercato di non perdere in questa edizione. Sostenendo il totale diritto alla convivenza equivoca e bivalente dell’operetta con il melodramma. Così come è nata. Così come si sentiva autorizzato a muoversi liberamente Bizet” (Lina Wertmüller, Programma di sala). “La scenografia è interpretata, scultorea, teatrale, lontana dal naturalismo usuale. È uno dei tanti segnali dello spettacolo… Consideriamo il teatro lirico abbastanza sacrale e con non troppe possibilità di prendersi delle libertà. Carmen oltretutto è un capolavoro di impianto veristico però non si può facilmente estrapolare da questa sua natura. Il problema è: la libertà o l’amore? Io, scelgo l’amore. Sono sicura che Carmen è con me!” (Lina Wertmüller e Enrico Job, Itinerario, dicembre 1986). “Dopo una Carmen cinematografica, ecco per me l’appuntamento con la vera Carmen, quella teatrale dell’Opéra Comique. Con Rosi avevo il grande respiro dell’aria aperta che dà il cinema, assieme alla felicità di rintracciare tratti ancora vivi della Spagna visitata da Gustave Doré, in un’Andalusia, tre anni fa, ancora agricola, antica, bellissima… Altro sono però la libertà e la felicità del teatro: la libertà assoluta al momento delle scelte e la felicità dei mille vincoli ai quali lega l’azione teatrale. Non sembri paradossale ch’io parli della felicità d’incontrare mille vincoli… In teatro sono proprio obblighi e condizionamenti a suggerire soluzioni, a sollecitare invenzioni, a indurre a sintesi esemplificatrici… I vincoli teatrali sono invalicabili e proprio per questo stimolano nel modo giusto; se non altro perché il luogo unico è già in sé una proposta di sintesi. Un condizionamento che mi spinse alla soluzione, poi adottata per questa rappresentazione teatrale di Carmen, fu che il palcoscenico del San Carlo non ha spazi laterali o di sottopalco per stivare le scene durante gli spettacoli. Dovevo quindi sacrificare una buona parte del palcoscenico a questa funzione per cambiare scena tra un atto e l’altro. Forse perché ho negli occhi i vasti paesaggi dell’Andalusia, ma più ancora perché amo il mistero di Carmen, la sfrenatezza che la consuma, la sua insaziabile sete di verità e d’avventura, non me la sentivo d’imprigionarla in un’unica scena o in quattro scene differenti ma anguste. Ecco dunque affiorare da un’oggettiva difficoltà, contrastante il desiderio di spazio di un personaggio, la necessità di un’invenzione. L’idea fu una scultura scomponibile e ricomponibile in modi diversi ma sempre tutta in scena; solo qualche elemento aggiunto o tolto a ogni composizione avrebbe connotato i one of us... Just as the characters of our dreams are always projections of ourselves, so is Carmen. Perhaps it is for this reason that this century, traversed by so many movements of febrile social growth and battles for freedom, has basically always tended to identify her as the symbol of freedom.A passionate, wandering Spanish gypsy... No, Carmen belongs to another family. Her woman’s curiosity becomes licentious to the French eye which sees her. Her anarchy becomes charm. Her very nature of freedom becomes a symbol. But the brilliant libretto devised by Meilhac and Halévy from Merimée’s novel lets one fact emerge: Carmen’s actual loss of freedom... And Carmen loses her freedom because something new and unexpected happens to her. She, who only has brief affairs, she, Carmen, falls in love... and she no longer has any intention of following any rule other than the one that sings within her... A Mediterranean reading in the ancient roots of this ambiguous heroine who, two-sided and obliging, evokes and stimulates different readings, just like the forest of psychoanalysis in which paths and views offer different alarming and mysterious perspectives. Carmen is greater that the others precisely because her ambiguity always sounds cymbals and castanets in order to indicate to us the rhythms of its possibilities. Carmen is at once desacrator and priestess of love. Her love of life leads her to seek death as a ritual. She is of the ancient stock of the Medeas and at the same time a flamenco dancer with castanets and a flower in her mouth. Bizet started to make an operetta, but while he was composing it its ritual force broke through the light tissue and emerged, powerful: melodrama. It is sunfilled and nocturnal. Even though the reassuring attraction exerted by the drama has, over the years, increasingly betrayed her double nature, it has gradually become a melodrama, fundamentally.And Paris? Paris, which becomes a dreamed of, never seen, Spain? This is another of the opera’s seductive double layers of meaning. It is precisely this Parisian essence, this ‘coté Operetta’, almost always sacrificed in the many glorious productions and reworkings of Carmen, which I have, on the contrary, attempted to maintain in this production. Upholding the operetta’s wholesale right to ambiguous and ambivalent coexistence alongside melodrama. Just as it was born. Just as Bizet felt himself freely authorized to act” (Lina Wertmüller, Programme Notes). “The set design is mediated, sculptural, theatrical, far from the usual naturalism. It is one of the many marks of the production...We regard opera as fairly sacred, with not too many possibilities for the taking of liberties. After all, Carmen is a masterpiece, a realistic opera which cannot, however, be easily extrapolated from this realism. The problem is: freedom or love? I opt for love. I am sure that Carmen is on my side!” (Lina Wertmüller and Enrico Job, Itinerario, December 1986). “After the film version of Carmen, here, for me, was the appointment with the real thing, the theatre production of light opera.With Rosi I had the freedom afforded by film, together with the pleasure of retracing - in Andalusia three years ago - the still extant traits of the Spain visited by Gustave Doré, a beautiful, ancient, rural existence...The freedom and pleasure of theatre is another thing altogether: the total freedom of imagination in the making of choices, and the pleasure of the thousand constraints by which theatrical action is limited. Let it not seem paradoxical that I should speak of the pleasure of encountering a thousand constraints... In theatre it is precisely the obligations and limits which suggest solutions, stimulate inventions and induce exemplary synthesis...There is no way around the constraints of theatre, and it is precisely for this reason that they provide the right form of stimulation. If only because the single location is already, in itself, a proposal of synthesis. One limit which drove me to find a solution adopted in this theatre production of Carmen was the fact that the theatre of San Carlo has no room at the sides of the stage or below it for the stoving of scenery during performances. I would therefore have to sacrifice a good part of the stage to this purpose in order to change the scenery between one act and another. Perhaps because I have in my eyes the vast landscapes of Andalusia, but even more because I love Carmen’s mystery, the wildness which consumes her and her insatiable thirst for truth and adventure, I didn’t feel able to imprison her in a single set or in four different but narrow scenes. So the need for invention arose from an objective difficulty standing in the way of a character’s desire for space.The idea was a modular sculpture which could be assembled and reassembled in different ways, but always all on stage; the addition or subtraction of the odd object to or from each composition denoted the places. Having rendered the whole stage of San Carlo available for action, without resorting to the illusory effects of painting, which didn’t anyway seem suited to the character’s concrete nature, I was able to give Carmen the Contrabbandieri - Gitane 13 luoghi. Conquistato così all’azione scenica tutto il palcoscenico del San Carlo, senza ricorrere a effetti illusori di pittura che nemmeno mi parevano adattarsi alla concretezza del personaggio, potevo regalare a Carmen l’aria che le è indispensabile. Un mio amico credeva nell’al di là e una volta mi disse che fin quando fosse stato qui sulla terra, per quanto si sforzasse di capire, non avrebbe mai potuto vedere più di tanto, e apriva l’indice e il pollice indicando uno spazio piccolissimo, quando invece fosse stato di là, allora finalmente avrebbe visto e capito, e allargava le braccia indicando tra una mano e l’altra uno spazio grandissimo. A me pare che Carmen, già qui tra noi, vedesse e capisse con quella apertura. Nel suo spazio mentale c’è un istinto, misteriosamente sicuro, lucido e disperato. Questo almeno mi pare d’intuire di lei ed è per questo che le forme delle mie scene si definirono angolose e dure come quella sua lucidità, ma modellate con il più consueto e amato dei materiali teatrali, come se il tavolato del palcoscenico si sollevasse ad assumere forme rocciose per rappresentare ancora una volta i luoghi deputati a celebrare amore e morte di Carmen” (Enrico Job, La mia Carmen, Il Mattino, 3 dicembre 1986). “Già, la regista: Lina Wertmüller. Gran protagonista doveva essere lei. E così è stato. Insieme con Enrico Job ha costruito una Carmen che taglia corto con tutta l’oleografia...” (Gino Cavallo, Carmen, uragano di passioni che viaggia in cabriolet, Il Mattino, 11 dicembre 1986). “Per Cesare De Seta, il meglio della serata lo ha dato Enrico Job con le sue scenografie, ‘molto marcate nel senso delle novità: e soprattutto in un ambiente come quello della lirica, viziato storicamente da ripetitività’” (Generoso Picone, Quando al foyer del teatro si specchia una città, Il Mattino, 11 dicembre 1986). La Wertmüller ci regala “la Carmen più sensuale e scatenata che il palcoscenico abbia avuto… tutta nuova, affascinante, è la Carmen dello scenografo Enrico Job: un’immensa scultura lignea tutta praticabile, con corridoi, scale, sottopassaggi; una scultura che è sostanzialmente una roccia e che si apre, si propone in diverse angolazioni fornendo ogni volta scene sempre diverse e sempre belle. Il legno riscoperto nella sua carnalità, ancora una volta, nella sua terrestrità, ancora una volta. Il palcoscenico è già segnato, prima che l’opera inizi, da enormi scialli andalusi che piovono dall’alto e restano presenti come cieli per tutta l’opera. E sono bellissimi anche i costumi disegnati da Job, attraenti anche nell’aggiornamento della collocazione dell’opera al primo Novecento” (Michelangelo Zurletti, Carmen o la carnalità, la Repubblica, 12 dicembre 1986). “Il tutto si svolge sulle scene di Enrico Job, belle se prese in senso assoluto, forse troppo stilizzate e nette rispetto a una musica così drammatica e cangiante”(Alfredo Gasponi, Carmen travolta da un’insolita regia, Il Messaggero, 12 dicembre 1986). “C’è una gran voglia di parlare, di esprimere giudizi, alla fine dello spettacolo. Lucio Amelio, gallerista:‘Ho visto una Carmen sensuale e carnale. L’idea giusta. È la prima volta che vedo Carmen all’Opera e che non mi viene da ridere’. Il maestro Mario Bartolotto: ‘La Carmen va realizzata esattamente come Bizet l’ha scritta. Con questa edizione ci sono riusciti. Deve essere un’opera divertente, non una tragedia greca’ ” (Ermanno Corsi, Lo scandalo di una sigaraia in cabriolet, la Repubblica, 12 dicembre 1986). Lo spettacolo, ripreso in diretta TV, nonostante i limiti della ripresa, è stato accolto con grande successo e coinvolgimento:“il colore e l’impeto della rappresentazione erano tali che per forza si sono trasferiti sul video” (Ugo Buzzolan, Quell’ardente gitana che ha stregato la TV, La Stampa, 12 dicembre 1986). 136 air she needed to breathe. I had a friend who believed in heaven, and he once explained to me that as long as he was alive, however much he might strive to understand, he would only ever be able to see so much, and he indicated a minute space between his thumb and forefinger. But once he had gone to heaven, then he would finally see and understand everything, and he stretched out arms so as to indicate a much larger space between one hand and the other. It seems to me that Carmen, while still on this earth, already saw and understood with that breadth of vision. Her mental space is that of an instinct which is mysteriously certain, lucid and desperate. So much at least I think I have intuited in her, and it is for this reason that the shapes of my scenery were angular and sharp, like her terrible lucidity, but modeled out of the most usual and best-loved theatrical materials, as if the floor of the stage had risen up and taken on the shapes of rocks in order in order to represent, once more, the spaces delegated to the celebration of Carmen’s love and death” (Enrico Job, La mia Carmen, Il Mattino, 3 December 1986). “Of course, the director: Lina Wertmüller. She had to play an important part. And so she has.Together with Enrico Job, she has created a Carmen which does away with all that is unoriginal...” (Gino Cavallo, Carmen, uragano di passioni che viaggia in cabriolet, Il Mattino, 11 December 1986). “According to Cesare De Seta, the best contribution was made by Enrico Job, with his sets which are “very marked in the sense of their innovations: and especially in an environment like that of opera, which traditionally has the vice of repetitiveness’” (Generoso Picone, Quando al foyer del teatro si specchia una città, Il Mattino, 11 December 1986). Wertmüller has given us “the most sensual, unbridled Carmen the stage has ever seen... Set designer Enrico Job’s Carmen is all new and fascinating: a big wooden sculpture which is all moveable, with corridors, stairways and underground passages. The sculpture is basically a rock which opens and presents itself in different angulations, each time forming scenes which are always different and always beautiful. Wood is rediscovered once again in its carnality, once again in its earthiness.The stage is already decorated, before the opera begins, with enormous Andalusian shawls which rain down from above and remain present like skies for the whole of the opera. And the costumes designed by Job are also extremely beautiful, also attractive in the updating of the setting of the work to the early twentieth century” (Michelangelo Zurletti, Carmen o la carnalità, la Repubblica, 12 December 1986). “Everything takes place on Enrico Job’s sets, which are beautiful taken on their own, but perhaps a little too stylized and clean-cut in the face of such dramatic, textured music” (Alfredo Gasponi, Carmen travolta da un’insolita regia, Il Messaggero, 12 December 1986). “Everybody wants to talk, to express their opinion, after the performance. Lucio Amelio, gallery director:‘I have seen a sensual and carnal Carmen.The right idea. It is the first time that I have seen Carmen at the Opera without wanting to laugh’. Musician Mario Bartolotto: ‘Carmen should be produced exactly as Bizet wrote it. In this production they have succeeded. It should be an amusing work, not a Greek tragedy’” (Ermanno Corsi, Lo scandalo di una sigaraia in cabriolet, la Repubblica, 12 December 1986). The performance, broadcast live on TV despite the inherent limits, was a great success and made a deep impression:“the production was of such colour and force that this was necessarily conveyed even on video” (Ugo Buzzolan, Quell’ardente gitana che ha stregato la TV, La Stampa, 12 December 1986).

Scarica