Political Publishing and Its Critics in Seventeenth-Century Italy Author(s): Brendan Dooley Source: Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, Vol. 41 (1996), pp. 175-193 Published by: University of Michigan Press for the American Academy in Rome Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4238741 . Accessed: 16/11/2013 06:08 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. . American Academy in Rome and University of Michigan Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 143.239.102.1 on Sat, 16 Nov 2013 06:08:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions POLITICALPUBLISHINGAND ITS CRITICS IN SEVENTEENTH-CENThRY ITALY BrendanDooley The communicationsrevolutionof earlymodern Europe occurredin three dimensions. Two of them were coveredby ElizabethEisensteinin her influentialThe PrintingPress as an Agent of Change(Cambridge1979)-namely, the religiousand the scientific or scholarly.The third dimension,that of politics, has been the object of a body of work that has grown particularlyover the past decade. Joining the hitherto distinct fields of histoire du livre, intellectual history and the history of political behavior,this researchhas sought to trace the influence of printedliteratureupon political culturesas far back as the beginning of the seventeenthcentury,and even earlier. This researchsuggests that printed publicationsof various sorts, including the newlyinvented newspapers,may have wielded a predominantinfluence in building political consciousness and affecting the outcomes of events in earlymodern Europe. If true, this suggests that the rich repertoireof behavioravailablefor expressingpositions regardingthe exercise of power in this period more frequentlyincluded written discourse and rationalpersuasion than was previouslyestimated,along with the exchange of visual symbols and gestures.Indeed, recentworkon Francehas uneartheda significantprintedchallengeto rulership as early as 1614, when Henry II of Bourbon,prince of Conde, mounted a written assaultto accompanyhis militaryassaultupon the regencygovernmentof Mariade' Medici duringthe minorityof Louis XIII.1And while parryingthe militaryassault,the regencygovernmentshot back with a series of pamphletsdefending its position. Both sides appearto have believed they could mobilize enough minds to be able to recruittroops or preventothers from doing so; and both sides apparentlybelieved they could establishpolitical consensusby argument and persuasion.In the Dutch Republic, pamphletwars of a similarsort occurred at every importantconjuncture.2The prospectivetruce suggestedby Jan van Oldenbarneveltduring the revolt from Spainwas hotly debatedin printbefore it was finallydeclaredin 1609. Later, the orthodox Calvinistonslaughtagainstthe splintergroupled byJacobus Arminiusin 1618 provoked a debate about religiousfreedom and tolerancein the new state. And the unfolding of events in Germanyroused Dutch supporterson each side of the ThirtyYears'Warto express their views. Meanwhile,in England,the circulationof literatureopposing the forced loan in the 1620s helped harden the opposition of membersof Parliamentto the crown's I JeffreyK. Sawyer,PrintedPoison.PamphletPropaganda, Beginningof IdeologicalConsciousnessandSocietyin the Faction Politics and the Public Spherein Early Seven- FrenchReformation(Cambridge1981). teenth-Century France(Berkeley1990).DonaldR. Kelley tracesthe use of printedmaterialto formpoliticalcon- 2 Craig Harline,Pamphlets,Printingand Political Culsciousness as far back as the sixteenth century,in The turein the EarlyDutchRepublic(Boston1987). This content downloaded from 143.239.102.1 on Sat, 16 Nov 2013 06:08:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 176 BRENDANDOOLEY innovativefinancialprocedures.3And the role of informationgrew until by the 1640s, securing public opinion was a key elementin politicalstrategieson either side of the Englishcivil war,and this was done in a mannerfar moreexplicit and dynamicthan anywhereelse.4 It was no accident that the period's most famous treatise on freedom of the press, Milton's Areopagitica, was writtenhere. Otherareasof Europesharedin these developments,although they are less studied. Among them Italy,which had an active printingindustryat the time with no less than 160 centersall down the peninsulafromTurinto Palermo,is a case worth analyzingin some detail. To attemptto prove the efficacyof seventeenth-centuryprinted appealsby gaugingthe meaningfulattitudes amongtheir broad readingpublics is to stretch the availableevidence beyond credibility;and this is one reasonwhy the alternativeapproachof JiirgenHabermas, more often found in studies on the eighteenth centuryand later, has recently been reproposed for the earlymodernperiod.'For Habermas,more importantthan actualpoliticalattitudes was the emergenceof structurespermittinga diversificationof the activitiesof private persons,leadingto a changein the rapportbetweenthem and the public authorities.In other words, political communicationnetworksbrought about political communication,not vice versa;just as passengersdo not createrailways,railwayscreatepassengers.Before the emergence of such structures,Habermascontends,the public spherebelonged entirelyto the ruling classes. Vis-a-visthe subject,this spherewas where the status of those classeswas represented and reinforcedby ceremonial.With the consolidationof commercialcapitalismand the formationof a recognizablebourgeoisie,the spherebelongingto privateindividualsand their familiesbegan to take on public characteristicsof its own. New channelsof communicationopened up, includingnewspapers.In privategatheringplaces-coffee houses, salonsprivateindividualswere broughttogetherto form an alternativepublic sphere where interests could be discussed. Meanwhile,a public conscience in opposition to public authority began to emerge, as men of letters began to appeal to the tastes of wider audiences and to criticizethe courts.Literaryjournalswere formed,and so also eventuallywere journalsconcernedwith privatelife. While the privatespherebeganto take on public characteristics,the formerpublic spherebegan to reachinto the privatesphere.The rulingclassesbeganto treat their subjects as a "public"by publicizing decrees and actions in newspapersand propagandapamphlets.Finally,state powercameto be seen and contendedfor, in print and everywhere else, as a means for economic advancement,and the bourgeois public sphere came into its own. Useful though it is, the account of Habermas,at least in the light of recent work, does not seem entirelysatisfactory.It places the changefrom a narrowto a wider public sphere at 3RichardJ. Cust, "News and Politics in EarlySeventeenth-Century England," Past and Present 112 (1986) 60-90. In addition, Cust, TheForcedLoanand English Politics, 1626-28 (Oxford 1987). However, MarkKishlanskyurges caution in giving too great importance to political issues in parliamentaryelections in this period, in ParliamentarySelection. Social and Political Choicein EarlyModernEngland(Cambridge 1986). 4Thomas N. Corns, UncloisteredVirtue:EnglishPolitical Literature,1640-60 (Oxford 1992). I Sawyer,(as n. 1) 10, citesJiirgenHabermas,TheStructuralTransformation of thePublicSphere,tr.ThomasBurger (Cambridge,Mass. 1989) [originallyStrukturwandel der Offentlichkeit (NeuwiedandBerlin1962)].Habermaslater provided a summaryof his argument,in "The Public Sphere:An EncyclopediaArticle,"New GermanCritique 3 (1974)49-55. Amongstudieson the eighteenthcentury which refer to Habermasis Keith Baker,Inventingthe FrenchRevolution(Cambridge1990),chapter8. I explain otheruses of the workin my "FromLiteraryCriticismto SystemsTheory:TwentyYearsofJoumalismHistory," Journalof theHistoryof Ideas51 (1990)461-86. This content downloaded from 143.239.102.1 on Sat, 16 Nov 2013 06:08:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions ITALY IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ANDITSCRITICS PUBLISHING POLITICAL 177 too late a date. Furthermore,it does not take adequateaccountof developmentson the continent. What fuelled the transitionfrom the representativepublic sphere to the bourgeois public sphere, he claimed, was a combinationof emergentcapitalism,a rising commercial class, a commercialorientationin government,and a free press. And since these elements seemed to him to have emergedfirst in England,he saw profound differencesbetween the "Englishmodel" and the "Continentalmodel" of development.Holland escaped his gaze entirely;and realchangeoccurredin Franceonly in the mid eighteenthcentury,he contended, and in Germanyafter 1789. If recent studies are right,however,the privatesphere began to take on public characteristicsin manyplaces long before commerceand mercantilismwere at their height, and the press, in spite of censorshipconstraints,was instrumentalin bringing about this result. In the Italian states, the change to a wider public sphere occurredroughlyat the same time as recentwork has found it to have done elsewhere,and the best proof is a sourcethat is both ubiquitous and still relativelyunused-namely, the views of contemporaryobservers. At the time, the new part playedby printedtexts was regardedas a political event of epochmaking importance.Varioustheories were advancedconcerningthe dangers and benefits. Such theories often profoundlyaffectedthe way governmentsorientedbehaviortowardsubject populations.For this reason,the earlyeighteenth-centuryNeapolitanjuristand historian GiambattistaVico made them part of the complex of characteristicsthat distinguishedeach period in the developmentof civilization.The present essay intends to trace their development in Italy from 1620 to the time of Vico. Contemporarytheoriesaboutthe communicationof politicalinformationin seventeenthcenturyItaly went throughtwo stages, which can be very brieflyoutlined here and at much greaterlength later accompaniedby examples.In virtuallyall the majorstates, from the republic of Veniceto the kingdomof Naples,the predominantearlyseventeenth-centurytheory insisted upon secrecy.To understandthe controlmechanismsupposedin this theory,the notion of monopolyis helpful. In this stage, informationof anykind-on militaryevents, internal political change, and the like-was regardedas subjectto carefulcontrol by the governments concerned,to be administeredbit by bit as the occasiondemanded,and carefullycontrolled at the variouspoints where it might enter a state. The audiencefor printedliterature was regardedas passive until enflamed and altered by novelty,which had therefore to be avoided wheneverinformationwas administered.The new theory that emerged aroundthe second half of the centurymight be called, for contrast,the free marketof information.According to this theory,the audiencewas conceivedto be anythingbut passive.It exercised a powerful and inexorabledemandon information,which poured out towardsit from whatever producerwas most readilyavailable.It preferredbad informationto good by a sort of Gresham'slaw, on the basis of what could most easily be obtained. Controlswere seen as counter-productive,because they discouragedthe good and failed to stop the bad. A free marketand a few dependablescribblerswere regardedas the only alternative.The transition from the monopoly theory to the free markettheorywas not abrupt;indeed, proponentsof the earliertheorycan be found throughoutthe century,just as hints of the latertheorycan be found earlier.Moreover,some of the best expressionsof the later theoryoccurredlong after a basic sea-changehad alreadytaken place; and indeed this happenedin differentplaces at differenttimes. These caveatsshould be kept in mind duringthe following account. What broughtabout the best expressionof the monopolisttheoryof communicationwas a crisis:the outbreakof the ThirtyYears'Warand the first avalancheof political pamphlets This content downloaded from 143.239.102.1 on Sat, 16 Nov 2013 06:08:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions BRENDANDOOLEY 178 describingand analyzingthe events in Germany,Holland and eventuallyin Italy and defending or impugningthe actionsof the statesconcerned.The Renaissancebarrierto the publication of informationburst before this onslaughtand the secrets of the cabinets of Italy and elsewherewere exposed to view. The gestureof providinginformationto the readerwas regarded by some officials in the variousstates as damagingenough in itself because it suggested that the higher affairsof governmentwere somehow of general interest. When the informationso provided was manifestlycontraryto the interests of the local government, extraordinarymeasuresseemed to be in order. Among the first of the officialsof the variousItaliangovernmentsto talk about the measures necessaryto preventthe effect of perniciousliteraturewas Paolo Sarpi, counsellorto the Venetianstate on mattersconcerningthe press. Most famousnow for his Historyof the Councilof Trent(1619), Sarpihad been firsthiredby the VenetianSenateto extricateit from the so-calledInterdictcontroversywith Romein 1606, when Pope Paul V placed heavysanctions on the Republic for its policy of having ecclesiasticstried in secular law courts.6In 1621, he was called upon to discuss the circulationof a pamphlet attributedto Hermann Conrad, Baron von Friedenberg,a Habsburg sympathizerin the Thirty Years' War,who claimedthe Venetiangovernmenthad made a deal with the Protestantstates to help save the Palatinatein exchange for certainfavors in the Germanspice marketin the early stages of the war.7This was a seriousindictment,suggestingthat Venicecould not be trustedas an ally to the Catholic princes and raisingsuspicions about the piety of its intentions in defending its controlover the local Churchin the Interdictcontroversy.The Venetiangovernmentnaturallybannedthe book, and Sarpitried to providesome guidancefor furtheroccasionsof this kind. as its government Somewritings,by defamingthe authorityof the stateandportraying bothamongits neighborsandamongits subjects the state'sreputation weak,undermine of noveltieswhicharenevertried theintroduction to sucha levelthatdisdainencourages thatarereputedpowerful by enemiesin warorbysubjectsin revoltagainstgovernments asperfidiousto its neighbors andeffective.Otherwritings,by depictingthegovernment andunjustandunlovingto its subjectsrenderit odiousto both. But the most pernicious of all, in Sarpi's view, and indeed the group to which the recently banned book belonged, "is a third type of writings, those that impugn the piety of the Republic in religious matters and so destroy the subjects' faith in it and remove their affection for the Prince."8The reader,according to Sarpi, was ordinarilya passive receptacle of information, believing whatever was written and adjusting his loyalties accordingly. Sarpi was well acquaintedwith the many avenuesfor the diffusion'of printed information in the seventeenth-centuryItalianworld. Wordof mouth was still the most importantin 6 These events are analyzedby WilliamJ. Bouwsma,in Museo Correr,Misc.Correr1099, cc. 21 ff. Veniceand the Defenseof RepublicanLiberty(Berkeley 8 Scrittigiurisdizionalistici, ed. GiovanniGambarin(Bari 1968). 1958)221.Thisperiodin Sarpi'slifeis analyzedby Gaetano ' The pamphletin questionwas Istruzionesecretissima Cozzi,"Notaintroduttiva," in PaoloSarpi,Opere,ed. G. dataa FedericoV contepalatino,printedin severallan- andLuisaCozzi(Milan-Naples1969)3-37. Forhis efforts guagesin 1620. A manuscriptof the work is in Venice, duringthe Interdict,thereis Bouwsma(asn. 6). This content downloaded from 143.239.102.1 on Sat, 16 Nov 2013 06:08:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions POLITICAL PUBLISHING ANDITSCRITICS IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY 179 a society with less than fifty percent literacy (still a high figure for the time); and writings quickly became the subjects of discussions availableto all. "Theyencourage conversation and providematerialfor the discoursesof the disaffectedandthe self-interested,who insinuate themselvesinto the open ears of the simple-minded,seducingthem and impressingupon them concepts with perniciouseffects."Printedworks could enter the world of oral culture especiallyvia the pulpit and the confessional."Theyencouragepreachersand confessorsto administertheir sinister offices in confessions and in other religious conversationswith an effectivenessthat we do not need to learnfromhistory."9This, he suggested,was the reason for the assassinationof Henry IV of France by FranqoisRavaillac,a court clerk with antiProtestantsympathiesand a fondnessfor Catholicoratory. In the event that such works could not effectivelybe prohibited,well-meaningstate officials might be tempted to engage in activeliterarycombat. "Allthat remains,"such officials might be led to think, "is to blunt the blade" of the dangerouswritings "andweaken their effect by opposing them with other writingsthat show them to be malicious and false and clarifythings enough to confound the spiteful, confirmthe sentimentsof the well-affected and impress the truth upon the undecided. ..."10 Renaissancerhetoricalskill, then, might come to the rescue.But no one knew better than Sarpithat this too had its perils.First of all, what if the opponentwas more humorousthanyou were? "Neverattemptto respondto writings that speak evil with brevity and wit, even if falsely,when the defense requiresa long narrativeor discourse,since brief and witty expressionsimpressthemselveson and take over the mind, whereasa long discoursetires it to such an extent that it will never open up to the truth."Next, what if the defense could be more damagingthanthe criticismitself?The truth can sometimeshurt, Sarpinoted, for the public dealingsof a government,based on a calculus of the lesser evil, are bound to appearsuspect to an ignorantprivate person bound to conventionalmorality. No state has been nor can be without very greatimperfections.... The [Venetian]Re- publicis by no meansimmuneto thehumancondition.Itsdefectscouldbe exposedand censured and used to condemn the whole governmentby anyonewho wants to offend and create a bad impression;they cannot be defended, can scarcelybe hidden, and to makeexcuse for them is to admitthem, and humanmalicedoes not listen to excuses. Faced with the futilityof all the other alternativesto the governmentalcontrol of information,Sarpimade a startlingsuggestion.The best strategy,he suggested,is to pay attention to events as they occur and publish a narrationof them with argumentssupportingthe side that fits one's interests and increasesone's advantage.He took the example of the recent pamphletwarbetween the Princeof Conde and the regencygovernmentof Mariade' Medici. "Whenanythinghappens that affects them, they immediatelycome out in print turningthe fact to their own advantage;and even when they do not have a present need, they do it in order to prepare opinions usefully for the future."When adopting this strategy,however, speed was of the utmost importancefor two reasons.First of all, audienceshave limited patience. "Whenthe events are new. . . recent curiosityexcites everyoneto read,whereasafter a few daysno one wants to hear about them anymore."Secondly,audiencesmakesnap judgments. "Thefirst impressionis usuallythe most effectivefor holding the mind and arousing 9Scritti giurisdizionalistici, 221-22. 10 Ibid., 222. This content downloaded from 143.239.102.1 on Sat, 16 Nov 2013 06:08:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions BRENDANDOOLEY 180 the emotions.""1 What Sarpi wanted could be called a government information office. By offering readers their first taste of what was going on in the world and tinting information in the proper way, the republic could ensure that information from other sources would be discounted or ignored. Sarpi thus pointed, however tentatively, toward the second stage in seventeenth-century communications theory-the theory of the free market. Information must be administered in carefully controlled doses, yes; but the job of control is complicated by the existence of competing information suppliers with contrary interests, who cannot be eradicated. Where there is competition there is a market, and where there is a market there are market forces. The audience therefore is not wholly passive; it allows itself to be enflamed and aroused by whoever captures its attention. And where the economy of communication cannot be completely controlled, government must compete better for a share of the market. After having come so far, however, Sarpi drew back. He rejected his own suggestion for a government information office as soon as he made it; and his reasons reveal still more about communication theories in the world of the early seventeenth century. For one thing, he protested, no printer in Venice would ever want to be involved in such a project, considering the number of powerful senators who might object to this or that feature of a story, leading to interminable quarrels and negotiations, and nothing getting printed. But his most important objection was that the gesture of verbal defense and explanation of policies placed the government in an attitude of subservience to the audience and opened up the public sphere to unnecessary interference from private persons. This was to be avoided at all costs. Said Sarpi: Everyoneconfessesthat the trueway of rulingthe subjectis to keep him ignorantof and reverenttowardpublic affairs,sincewhen he finds out aboutthem he graduallybegins to judge the prince'sactions;he becomes so accustomedto this communicationthat he believes it is due him and when it is not, he sees a false significanceor else perceives an affront and conceives hatred-and what is said of subjectscan be applied proportionately to neighbors.This reasonis so strong that it has no responsein cases where [the argumentsof the government]have not [yet] been published and where its opponents are not expected to publishcontraryones;in such cases the subjectwould not be kept in ignoranceand reverence,but the door would be opened to the contraryopinion formed by the readingof opposingmanifestoes,which the public serviceinsists must be prohibited and once diffusedmust be eradicated.12 Making the subject think about politics could open a Pandora's box. Having rejected his own best suggestion, Sarpi excused himself from making any further pronouncements, and, for the moment, nothing further was done. The Venetian government fully acknowledged the dangers of opening the cabinets of princes up to the scrutiny of the whole population. One of the next victims of this policy was not even the product of an enemy foreigner but of Venetian official historian Nicolo Contarini, later doge. He wrote the state-sponsored history of the Republic from 1597 through 1605 and left it unfinished at his death in 1631. In it, he analyzed the policy of Venice toward Rome, France, and the Habsburg Empire in a delicate period, showing the disagreements among the senators where they occurred as the European power balance of the late Renaissance began to fall apart and a clash between Venice and the papacy loomed, due to the 11 Ibid., 228. 12Ibid., 230. This content downloaded from 143.239.102.1 on Sat, 16 Nov 2013 06:08:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions ITALY POLITICALPUBLISHINGAND ITS CRITICSIN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY 181 Republic'sinsistence on keeping control over the local Church.13And like his predecessor Paolo Paruta,he wrote in Italian for the intelligenceof his fellow countrymen.'4However, the government-appointedcensors decided his accountwas too candid for comfort. "In his introductoryremarksabout the varioussenatorsinvolved,"they noted, "[he] explainsmuch that can allow men to find out how to act politically"(in Italian,politicamente-i.e., to act with skill in a political setting)." No one in the VenetianRepublicwas allowed to act with political skill at bringingpressureto bear for the enactmentof legislationor the changingof policies, except the Venetiannobility,designatedby statuteas the exclusivepossessorsof the franchiseand as the exclusive holders of the most importantoffices. Accordingly,the governmentsuspendedthe printingof the work and enjoinedthe next official historian,Andrea Morosini,to observescrupulouslythe new obligationto write in Latin.He, in turn, directed his work not to a largepublic of Venetiansand Italiansbut to the patricianelite and scholars "whereverLatin is understood."16 The attitudesof Sarpiand the Venetianelite were typicalexamplesof more widespread views. In the grand duchy of Tuscany,the proponentof ideas similarto Sarpi'swas Virgilio Malvezzi,a Bologneselawyerin the entourageof his father,governorof Siena,a city subject to the grand duke. In his Discourses upon Cornelius Tacitus, dedicated to Grand Duke FerdinandoII, he declaredthat "all states have certainfoundationsor as we call them, seHe councrets,by which they governthemselves,both for conservationand augmentation."'7 selled princes to "speakobscurely,"addingthus to their majesty,and to avoid "layingthemselves open to all men'sview."'18Political informationwas, for Malvezzi,an attributeof majesty.Just a short time before, Neapolitan-bornFlorentineresidentScipioneAmmiratowrote an entire treatise,On Secrecy, advisingagainstrevealing"inappropriatethings"[non honeste cose] such as the secrets of princes or the affairsof ministersand nobles that were better to "keep quiet."19All agreedthat the audiencefor political informationwas passive as long as 13 The work is excerptedby Gino Benzoni and Tiziano The authorityon Contariniis still GaetanoCozzi,II doge Zanato, in Storici, politici e moralisti del Seicento NicoloContarini(Venice1958). (Milan-Naples1982) 135-444. 16 AndreaMorosini,Historiaveneta,which I consulted 14PaoloParutato "ilnobileNN," in ApostoloZeno,"Vita in Istoricidelle coseveneziane,vol. 5 (1718), pt. 1, p. 2: di PaoloParuta,"prefixedto Paruta'sHistoriaveneziana, "Cummihi a supremoDecemvirumConcilioinjunctum in Istoricidelle coseveneziane,10 vols., ed. Apostoloand esset, ut scriptisrerum,quae nostra aetategestae sunt, PiercaterinoZeno (Venice1718-22),vol. 3 (1718)xx: . . . memoriamcomplecterer,cuperetqueanimusnon intra Mi parevanonpoterfuggirognibiasimo,s'iotantostimato unius provinciaefines, sed quacumquepriscaeRomanavessiil piaceraglistraniericol porreognimiostudionello orum linguae notitia pervasit, nobilissimae atque scriverenellalinguaLatinaa piu di loropartecipe,la storia antiquissimaeReipublicaegesta perlegi . . ." delle cose nostre,che nessunaoperao curaavessivoluto porreperpiacerea nostrimedesimiItaliani:moltideiquali, '7Discourses uponCornelius Tacitus, tr.RichardBaker(Lonpersoneper altrodi alto ingegno,per averealtrovevolta don 1642) [orig. DiscorsisopraCornelioTacito(Venice l'indoleloro, non hannocognizionedellalinguaLatina." 1622)] 198.A discussionthatlooks at Malvezzi'splacein The currentauthorityon Venetianhistoriography in the seventeenth-century thoughtfroma slightlydifferentviewRenaissanceis EricCochrane,HistoriansandHistoriogra- pointis RichardTuck,PhilosophyandGovernment (Camphyin the ItalianRenaissance(Chicago1984). bridge1993),chap.3. Theonlyfull-lengthstudyis Rodolfo Brandli,VirgilioMalvezzi,politicoe moralista(Basel1964), 13 The report of CounsellorsScipione Ferramoscaand fromwhichonlythe biographicaldetailsherearetaken. LodovicoBaitelliis recordedin Emmanuele Cicogna,Delle vol.3 (1830)289.Thenumerousmanu- '8DiscoursesuponCorneliusTacitus,378. iscrizioniveneziane, scripts that nonetheless circulatedare discussed in T. Zanato,"Perl'edizionecriticadelle Historievenezianedi ' Scipione Ammirato, "Della segretezza" [1593] in Nicolo Contarini,"Studiveneziani,n.s. 4 (1980) 129-98. Opuscoli,vol. 1 (Florence1640) 315-48. This content downloaded from 143.239.102.1 on Sat, 16 Nov 2013 06:08:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 182 BRENDAN DOOLEY novelty did not bring out the vice of curiosity;otherwise,even the circulationof facts about currentpolicies amongthe populationcould sparkcontestationand oppositionto public pronouncementsof the politicalelite. Dealswiththis or thatpotentate,opinionsaboutthe Church, and so forth might detractfrom the image of perfect probity and justice they wanted their states to project.All agreedthat the public sphere,whetherin nominalrepublicslike aristocraticVenice or in ducal monarchieslike Florence,i.e., the spherewhere there could be real politics-decision-making, deliberating,counselling,and acting upon the concerns that affect the communityin its entirety-must be reservedexclusivelyto the politicalelite in order to maintainpower and security. Even those who disagreedwith this tradition'simplied goals acknowledgedthat a restrictedpublic spherewas the best way to attainthem. TraianoBoccalini,a provincialgovernor in the papal states and one of the great satiristsof the century,playfullysuggested that governmentsdid not uniformlyban the ideas of Niccolo Machiavellifrom the bookstoresin their states for pious reasons.They did so, instead, for fear that subjects might learn from him the principlesfollowed by rulingelites in the world of politics. Then those governments would no longer have meek and stupid flocks to watch, but clever and astute politicians, readyto contest their power at each opportunity.If the most worthwhilegoal of politics was power and security(andBoccaliniwas not altogethersurethat this was the case), a restricted public spherewas the only means. "Tryingto make simplemen cunningand to makemoles, which MotherNaturehad wisely madeblind, see the light, would be," accordingto the view satirizedby Boccalini,"to turn the world upside down."20 The changeto the next stagein seventeenth-century theoriesof communication,the stage that might be called the free markettheory,came aboutfor some of the reasonssuggestedby Habermas,but not necessarilyin the degree or order he suggested. One reason may well have been the growingnumberof privateassociationsin the Italian cities. Far more important than the coffee houses or salons mentionedby Habermasfor providingnew places for the discussionof commonconcernsby privateindividualswerethe academies.2" Actuallydating fromthe earlierRenaissance,these institutionscontinuedto developthe role assignedto them at their origins-namely, that of providinginformalplaces of encounterfor literaryrecreation and perfecting the art of conversation.Each was governedlike a miniaturerepublic, with a special, often whimsicalname, a distinctiveemblem, and an elected leader. Nobles and commoners,laymenand ecclesiastics,universityprofessorsand membersof the liberal professionstook equal part, often adoptingaliasesto conceal their unequalsocial positions. Activitiesincluded public lectures,poetryrecitations,games,competitions,and the publication of writingsboth serious and frivolous.Their statutes regularlyprohibited orations regarding "dangerous"topics directlyrelatedto religion or politics. "No one must read anything regardingtheology or sacred Scripture,from which we must abstain for the sake of reverence,"the foundersof the Academyof the Oziosi [the "LazyOnes"] of Naples enjoined, "andlikewise, nothing concerningpublic government,which must be left to the care of the FromRagguagli di Parnaso, vol. 1, ed. GiuseppeRua MicheleMaylender, Storia delle accademied'Italia, 5 vols. (Bari1910)328. A recentcriticalappraisalis in Maurizio (Bologna 1929-30). All work on academies,however, Viroli,From Politics to Reason of State. The Acquisition shouldbe readin the lightof EricCochrane,"TheRenaisand Transformation of the Language of Politics, 1250sanceAcademiesin the ItalianandEuropeanSetting,"in 1600 (Cambridge1992) 257-67. The FairestFlower: The Emergenceof Linguistic Consciousness in RenaissanceEurope,Proceedingsof the Conference 21 The indispensablereferencework on the academiesis at UCLA,December1983 (Florence1985)21-39. 20 This content downloaded from 143.239.102.1 on Sat, 16 Nov 2013 06:08:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions ITALY POLITICALPUBLISHINGAND ITS CRITICSIN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY 183 rulingprinces.""This did not preventthe more adventurousamongthem, such as the Lincei of Rome or the Investigantiof Naples, from takingpotshots at currentstate policies on education, or frombaitingthe local press censors,as did the Incognitiof Venice.The academies' ideal of "civilconversation,"which they defined as the meansfor "livingcivilly"together,no doubt helped define a sphere of sociability outside the sphere defined by government.23 And they responded so well to the growing needs of seventeenth-centurycultural and social life that the number of new foundations grew from 377 in 113 cities in the previous centuryto no fewer than 870 in 226 cities in the seventeenthcentury,reachinga peak around 1650.24 Another main reason for the change to the free markettheory of communicationmost certainlywas the recoveryof commerceafterthe depressionof 1620 and the plague of 1630, which depleted the populationof Veniceby a third, of Milanand Bresciaby nearlyhalf, and of Florence by an eighth.25For one thing, informationabout the situationin some of Italy's best marketsin Germanyand France came into great demand,and beginningin 1640 with Genoese writerPietro Castelli,entrepreneursand printersall over Italy began to set in type the manuscriptnewslettersthat had hitherto been circulatingamong a restrictedgroup of Furthermore,the economic crisistemporarilydislodgedthe Vediplomatsand big traders.26 netian printing industryfrom its position of dominanceover its counterpartsin the rest of the peninsula.27Printersin other Italiancities tried to take up the slack, and whereno printers existed, one or two were establishedfor the first time. But when the Venetianindustry began to recover in the 1640s, it regainedmost of the authors it lost, leaving the smaller printerselsewhereto make do with whateversorts of publicationsthe Venetiansdid not export, such as broadsidesand smallpamphletsthatwerenot worththe postageand transportation costs of interstatedelivery.And one item that the Venetianswould by no meansexport, Cited in Amedeo Quondam,"Laccademia,"Letteraturaitaliana,vol. 1, II letteratoe le istituzioni,ed. Alberto AsorRosa (Turin1982) 855. Quondamplacesmoreemphasis on the academiesas structuresfor social control than the evidence seemsto allow. 22 1965) 69-71, corrected according to articles in La demografiastoricadelle cittditaliane,Convegno,Assisi, 27-29 ottobre, 1980 (Bologna1982). The plagues'economic consequences are the subject of Lorenzo Dal italiana,secoli Panta,Le epidemienellastoriademografica 16-18 (Turin1980), chapter4. 23StefanoGuazzo,Lacivilconversatione (Venice1575)20. Quondam provides a handy table in "L'accademia," 890-98. In addition, Giuseppe Olmi, "'In essercitio universaledi contemplationee pratica':FedericoCesi e i Lincei,"in Universitd,accademiee societdscientifiche in Italia e in Germaniadal Cinqueal Seicento,ed. Ezio Raimondiand LaetitiaBoehm (Bologna1981) 169-99; andJean-MichelGardair,"I Lincei:i soggetti,i luoghi, le attivita," Quadernistorici 16 (1981) 763-87. The Investigantihavegenerateda considerablebibliography, outlined by Maurizio Torrini, in "L'Accademiadegli Investiganti, Napoli, 1633-70," Quadernistorici 16 (1981)845-83. Finally,concerningthe Incogniti,Ginetta Auzzas, "Le nuove esperienze della narrativa: il romanzo,"Storiadellaculturaveneta,vol. 6, II Seicento, ed. Girolamo Arnaldi and Armando Pastore Stocchi (Vicenza1983) 249-95. 24 26Theonlybiographyof the Castelliis by G. Gangemiin the DizionariobiograficodegliItaliani21 (1978)741-42. In addition, see ValerioCastronovo,"I primi sviluppi della stampaperiodica fra Cinque e Seicento," in La stampaitaliana dal Cinquecentoall'Ottocento, ed. V. Castronovoand Nicola Tranfaglia(Bari 1976) 26. For whatfollows,thereis valuablebibliographicalinformation in vol. 2 of Ugo Bellocchi, Storiadel giornalismo italiano,6 vols. (Bologna1974-77). Paolo Ulvioni, "Stampatorie librai a Venezia nel Seicento,"Archivioveneto, ser. 5, vol. 144 (1977) 93134. Whatfollows is based on an analysisof SuzanneP. Michel and Paul-HenriMichel,Repertoiredes ouvrages imprimisen langueitalienneau dix-septiemesiecle,vol. 1 (A-Ba),and vol. 2 (Be-Bz),(Florence1970-1980); id., en langueitalienneau Repertoiredes ouvragesimprime's dix-septiemesiecle conserve'sdans les bibliothequesde 2S Plague mortality rates are from Julius Beloch, France,7 vols. (Paris 1972-85); S. Piantanidaet al., italiens,vol. 1., seconded. (Berlin Autoriitalianidel Seicento,4 vols. (Milan1948-51). Bevolkerungsgeschichte 27 This content downloaded from 143.239.102.1 on Sat, 16 Nov 2013 06:08:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 184 BRENDANDOOLEY butwhichnonethelessseemedto promisesmallerprintersa relatively regularincome,atleast in comparison withthe usualspotprinting,wastheprintednewspaper. weremilitaryandpoliticalinforBy farthe mostsignificantcontentsof the newspapers mation.Asjournalists soughtto filltheirpagesbyextendingto thelimittheirstoriesof battles, of Europe,the subjectmatterof jourtreaties,andchangesof personnelin the governments nalismquicklyevolvedfrominformation to opinionson mattersto be decidedin government.The journalistsused new laws and policiesas occasionsfor politicalanalysis.True, noneof themwillinglyofferedhimselfas a scapegoatto the authorities by printingmuckraking storieson localpoliticsin a publication knownby everyonein townto be his ownproduct. Theycoveredlocal politicsin a generallypositivefashion.The Successidel Mondoin Turin,for example,reservednothingbut praiseforDukeCharlesEmmanuel's policyon law andorderin the principality of Piedmontandthe duchyof Savoy."Rigorous enforcement of theguncontrollaws,"it commented, "willmakethestreetssaferatnight."28 Nothingstopped the journalists, however,fromsayingwhattheywantedaboutexternalaffairs;andthemultitudeof Italianstatesprovidedan almostinexhaustible sourceof material.TheGenoa-based Gazzettadi Genovacoveredthe Italianepisodesof the warsbetweenFranceand Spainin 1656,on the eve of the Peaceof the Pyrenees;andwhatbeganas a reporton the effortsof theFrench,aidedby DukeCharlesEmmanuel II of Savoy,to dislodgethe Spanishfromtheir possessionsin Lombardy, turnedintoa lamenton thesenselessness of waranda possiblecall to the localgovernment to avoidinvolvement andto trustthe securityprovidedby Genoa's controversial alliancewithSpain."Thepeoplein theseareasfleeto theothersideof theriver [Po] to seekrefugewiththeirpossessionsin [thefortressof] Casale,"a citadelbelongingto the dukeof Mantua,"andsincethe Po is overflowing, andtheyhavetroublecrossing,the sightof thosepoorpeoplewaitingon the shoreallterrifiedby the sufferingandby the dangerof beingsurprisedby the Frenchexcitesunimaginable compassion."29 TheRimini-based Riminionewspapercriticizedthe Spanishgovernment in MilanandLombardy for allowing grainpricesto risedisastrously in the 1660s,whileat the sametimedrawingmenawayfrom the fieldsto be shippedoverto the recentlyresumedwarto regainPortugal.It then cited maladministration by the Spanishgovernment in the portof Finale,recentlypurchasedfrom Genoa."Thepeoplein thisstatethreaten[thegovernor]," it noted,"becausebreadbecomes moreandmoreexpensive,for whichtheyblamehis inabilityto govern."It contrastedthe governor's carelessness withLouisXIV'ssolicitudein prosecuting thecorruptfinanceminister NicolasFouquet."Thebloodof the poorcalledforvendettaandjustice,"it proclaimed; and "thekingwasmoved. .. by zealforgoodgovernment andby the desireto removeabuses."30 TheMacerata-based newspaper, Macerata, evaluated thepoliciesof theSpanishgovernment in Naplesin the wakeof the famineandplagueof 1656,whichhadstruckGenoaandmostof southernItalyandcostNaplesnearlyhalfits population; at the sametime,it emphasized the chiefvaluesthatall governments oughtto observe."Itis saidthatthe viceroyfrequently has 28 Enrico Jovane, II primo giornalismo torinese (Turin 1938) 81. a passare, fanno grandissima compassione il vedere quelle povere genti a trattenersi nella sponda di la tutti addolorati per i patimenti e per il pericolo di esser sorpresi dai francesi." 29 Gazzetta di Genova,22 September1657:"Sista ancora sul credere che vogliono passare il Po per attacare Frascarolo,in segno di che tutte le genti di quelle terre 30 Nevio Matteini, II 'Riminio":una delleprimegazzette fuggono di qua dal fiume per ricoverarsicon le di loro d'Italia. Saggio storico sui primordi della stampa robbe entrodi Casale,e percheil Po e grosso,e si stenta (Bologna 1967) 9-12, 45. This content downloaded from 143.239.102.1 on Sat, 16 Nov 2013 06:08:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions POLITICALPUBLISHINGAND ITS CRITICSIN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY 185 meetingsabout keeping the good governmentof this kingdomin peace, justice and prosperity,"it noted, "andfor this purposehe has loweredthe priceof meat and otherfoodstuffs."31 The emergenceof printednewspapersnot only in the largercenters-Naples, Bologna, Florence, Ferrara,Modena-but in everymedium-sizedcenter,from Maceratato Ancona to Foligno to Rimini,was for the communicationstheoristsof the time fair proof that previous theorieswere inadequate.Whatthe newspapersunderscoredparticularly, becauseof the printers)willingnessto bravethe perils of censorshipand commitcostlypaper,time, and type to a relativelyyoung, and in Italy,untried and experimentalgenre, was the existence of a constant, regular,and voluminousmarketfor politicalinformationamongthe populationsof the Italian cities, populations that currenttheory assumedto be apolitical and passive receptacles for informationto be administeredbit by bit. Indeed, newspapersonly added to the specter that had worriedSarpi:the avalancheof political informationassailingthe late Renaissancebarriersagainstencroachmenton a protected public space. Everymajorpolitical controversyseemed to call forth appealsto public sympathyfor the belligerents.One such controversywas the Piedmontcivil war from 163845. Essentiallya familyquarrelthat escalatedinto a noble frondewith both sides summoning reinforcementsfrom as many readersas possible and from the other Europeanpowers, the war startedwhen renegadeprincesTommasoand Mauriziodi Savoiatried to unseat the regency government of Marie Christine of Bourbon during the minority of Duke Charles EmmanuelI. An anonymouspamphletentitled The UnbiasedPoliticalHistorian,published by a sympathizerof Tommasoand Maurizio,aimedto attractpublic approvalfor the leaders' efforts to secure Spanishsupportagainstthe regency.32 Bewareof suggestionsabout a league of Italianprinces to expel the Spanishallies, it warned,because such leagues alwaysend up merelyfurtheringthe personalgainof the princesandtheirsympathizersandneverredounding to the public good. Worseyet, the only two powersthat could lead a leaguewere politically unstable:Rome changed generalswith everynew papacy,and Venice alreadyhad its hands full ensuringits sovereigntyover subject cities like Veronaand Brescia,to the residentsof which it resolutelyrefusedto grantthe privilegesof citizenship.Anotherpamphlet,TheShield andSpearof the Montferratese SoldierImpugned,publishedanonymouslyby hiredpen Vittorio Siri for sympathizersof Marie Christinein the same struggle, arguedthat because Spain's power in Italy had to be offset by France, the regent'sefforts to secure a French alliance ought to be supportedby everyone."3 Repletewith argumentsfrom commonsense and from history,such works sought to turn power strugglesinto battles of words. At the end of every majorevent, slapdashhistoriescame out, tryingto put government policies into a largerexplanatorycontext and makingclearwhich of them ought to be condemned. Genoese historianPietro GiovanniCapriataridiculedthe self-congratulatoryproclamationsof the Venetiangovernmentabout its policies during the plague of 1630, which had decimatedits population.Insteadof followinga carefullyconceivedquarantineplan like the Tuscangrandduke, the governmentunwiselydelegatedall sanitarymeasuresto the local neighborhoodsto observeandenforce,Capriatanoted. "Andtherefore,greatwas the scourge," 31 Macerata, 16 October1664:"Scrivonoche queil'Emin- of the quarrel are analyzed in Romolo Quazza, entissimoViceRetenessespesseConsulteperil buongovemo Preponderanza spagnuola (Milan 1950), chapter di quel Regno,quietee giustizia,e abbondanza,havendo 6. fattocalaredi prezzola camee altrecosecomestibili." 33 Lo scudo e l'asta del soldato monferrinoimpugnato 32 L'istorico politico indifferente (1641). The issues (Cefali 1641). This content downloaded from 143.239.102.1 on Sat, 16 Nov 2013 06:08:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 186 BRENDANDOOLEY he noted, "andthe mortalityof the people."" NeapolitanhistorianAlessandroGiraffi analyzed the MasanielloRevolt of 1647 in Naples, a tax dispute that escalatedinto a constitutional crisis with demandsfor more popularrepresentationin government,and was named for the rebel leaderwho held virtuallyunchallengedcontrolover the city for ten days. Giraffi attributedthe outbreakto short-sightedfiscal policies of the Spanishgovernmentand the Neapolitans'desire for freedom. "Fornaturehas clearlyinstilled in all men a detestationof slavery;so they are unwillingto put their necks into the yoke of a master-especially when the exorbitantexactionsimposed reducethem to the utmostgestureof despair."3 All this printedmaterialbegan to circulatemorewidelytowardthe mid-seventeenthcenturyas the censorshipapparatusitself beganto breakdown;and this was yet anothercauseof the change in theories about printed communication.In spite of their constantcomplaints, printersand booksellersactuallyfound manymethodsfor eludingthe authorities.In Naples, wherethe local censorshiphad the worstreputationof all, printerAntonioBulifonsent manuscriptsto nearbyPozzuoliif he could not get them approvedin the maincity.There,the ecclesiasticalrepresentativewas farmorelenientthanthe (asBulifonsaid) "scrupulousfellow"close To move dangerousbooks aroundItaly by and his successor,"whoalso causedproblems."36 withoutriskinginspection,he used the free ports.Entranceto Florence,for example,was easiapparatussucceededin stoppingthe circuest throughLeghorn.Evenwhenthe administrative lation of worksfor a time, the end resultwas often the oppositeof that intended.Romansatirist FerrantePallavicino,responsiblefor some of the most biting polemicsin his time against hypocrisy,the papacy,and the lasciviousunderworldof whores,procuressesand roue youths prowlingthe streetsof the Italiancities, made this a generalrule: "Prohibitionsso commonplace areno longerappreciated;andindeed,theymakebooksmorevaluable,so everyauthoris encouragedto beg for them in orderto increasethe valueof his compositions."37 Respondingto this demand,the writersof the newspapers,pamphletsand historiesthemselves acted as though their audienceswere active, not passive. "Youare impatient to see explainedin this gazette,"Pietro Socinitold his readersin the TurinSuccessidel Mondo,"the news written two or three times from Paris in the manuscriptletters about a battle" during the PortugueserevoltagainstSpain.38And again,"thechangein the currentsituation,"noted Amadore Massi in the Riminio, "[has blocked] the desired notice about things in the Levant.""Finally,Maceratareportedthat "theletters that the mailmanwill bring the day after tomorrow are eagerly awaited,"inasmuchas they were sure to contain informationabout PietroGiovanniCapriata,Dell'historia,vol. 3 (Genova 1652) 341; and, for the quote, vol. 1, 701: "Vi fece progressitali, che superandofrapoco tempoil maletutti i rimedi,e le provvidenze,rimasela curaquasi affatto, da chi governavale cose, abbandonata: onde grandissima fu la strage,e la mortalitadella gente." 34 22 (1992) 23-35. 36Lettere dalRegnoadAntonioMagliabechi,ed. Amedeo QuondamandMicheleRak(Naples1978)1, 119 (quote), 210. The view of Antonio Rotondo, "La censura ecclesiasticae la cultura,"in Storiad'Italia,vol. 5, pt. 2, I documenti(Turin1973) 1397-1492 shouldbe revisedin thelightof SergioBertelliandPieroInnocenti,Bibliografia machiavelliana (Verona1979)lviii and subsequentwork. AlessandroGiraffi,Ragguagliodel tumultodi Napoli (Venezia 1647), Prologo. Issues in the revolt are analyzed by RosarioVillari,TheRevoltof Naples,tr.James Newell with the assistance of John A. Marino (Cam- 37 II Corrieresvaligiato [Norimberga (=Venice), s.d. bridge, Mass. 1993). The standardaccount of histori- (1641)], ed. ArmandoMarchi(Parma1984) 99. ographyin the period, SergioBertelli'sRibelli, libertini ed ortodossinella storiografiabarocca(Florence1973), 38Jovane, (as n. 28) 47. is challengedby Peter Burke,"SomeSeventeenth-CenturyAnatomistsof Revolution,"Storiadellastoriografia 39Matteini,(as n. 30) 37. 35 This content downloaded from 143.239.102.1 on Sat, 16 Nov 2013 06:08:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions ITALY POLITICALPUBLISHINGAND ITS CRITICSIN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY 187 OWAT PIL AgS APPPA5I ~ 4'. .1 _' ~~ N / / ' do Aft 49~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~j _~~~~ . Fig. 1. Entitled "Agliappassionatiper le guerre,"the engravingis reproducedin Sapienzafigurata, MonumentaBergomensia,19 (Bergamo1967), plate 229. "some favorable change concerning Imperial arms . . . against the Turk."40The implicit assumption in the efforts of Pallavicino, in those of the pamphleteers in the Piedmont civil war, of Giraffi, of Capriata and the rest was that readers were eager to hear all sides of the story and to evaluate the various information products on the market before becoming enraged and enflamed by one or the other. A commonplace and self-serving writer's assumption but one which the political elites were ready to take seriously for the first time. More political information seemed to be available to more people than ever before. "Today more books are born every year," noted the late seventeenth-century Venetian printer-journalist Girolamo Albrizzi, "than previously in an entire century."41 And with the emergence of more media, media criticism began. "You who after silly tales are lusting / Anxious to hear rumors and reports, / Quickly, run and look at the gazettes, / And see if the news is good, fine, or disgusting"-wailed a Paduan pamphleteer.42A print (fig. 1) from 1684 by Bolognese engraver Giuseppe Mitelli, entitled "To the War Enthusiasts,"depicted the reading of a gazette among an audience apparently overwhelmed by the news. The city square in Bologna, where the public sphere was once defined only by the proclamations and the ceremonies of the local archbishop and his direct superior, the pope, or defiled by riot and revolt, now served as a metaphor 40Macerata, 18 September 1664: "Si attendono con grandissimo desiderio le lettere che portara dimani I'altro ordinario di Vienna sperandosi d'intender con esse qualche prospero avvenimento all'Armi Imperiali, che con l'ultime della Corte Cesarea si e saputo si trovassero in disposizione di appigliarsi a qualche buon impresa contro i Turchi." 41 The quote is from Galleriadi Minerva,1 (1696), 'Ai letterati." Anon., Istoria graziosa e piacevole, la quale contiene un bellissimo contrasto, che fd la cittd di Napoli con la cittd di Venezia, dove si vede la grandezza e la magnificenza di queste due gran cittd d'Italia (Padua: 42 Penada, n.d.), datable from internal references to the late seventeenth century. My quote is from the first unnumberedpage: "Voi che state sulle barzellette / Curiosi di saper chiassi, e novelle, / Veloci andate a legger le gazzette, / Se le nuove son buon, o brutte, o belle, /.. ." This content downloaded from 143.239.102.1 on Sat, 16 Nov 2013 06:08:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 188 BRENDANDOOLEY for a new public sphere of discussion and debate, verging on contestation.Yet in response to the heated public debate in late seventeenth-century Italiancities on whetherto ally with Franceor with Spain,Mitellicould only remarkacidly,"mynews reporters(novellisti), let me give you some news:this cryingout of yoursfor Franceand Spainis the greatestfolly thereis!" The reactionof the governmentsof the variousItalianstates to what now seemed to be not just an avalancheof information,but an inexhaustiblemarketthat demandedinformation fromeverypossiblesource,was to takefull advantageof theirown officialprintinghouses. By the 1640s, every state had designatedone, often the same house that had been printing governmentproclamations,notices, and certificatesfor years.In Turin,this was the shop of Giovanni Sinibaldo,successorto the shop that the Savoydukes had helped establishin the previous centuryas part of an effort to encouragethe developmentof the newly introduced printingindustry.In Rome, it was the TipografiaVaticana;in Milan,the Malatestafamily;in Bologna,the Manolessi;in Modena,the Soliani;in Florence,GirolamoSignorettiand Pietro Nestri,closelyfollowedby VincenzioVangelisti,PieroMatiniandFrancescoOnofri;in Modena, GiambattistaGrana;in Ferrara,the Marestifamily;and in Venice,the Pinellifamily.43 These firmsthe governmentsencouragedor even commissionedto celebrate,praise,and explainthe veryactionsthatwerebeing regardedwith skepticism,deridedand even impugned in the independentpress.The Ferraresegovernmenthad its printinghouse publishchronicles of Ferraresefamilies,lists of officials, and "allthe most beautifuland curiousmemories,sacred and profane, and every most heroic and excellent action of many lords, prelates and princes of the House of Este," the local dynasty."The Florentinegovernmentinvolved its official printinghouse in alertingsubjectsto the affairsof the Habsburgdynastywith which the Mediciwas alliedby marriage;it publicizedthe mourningfor GrandDuke FerdinandoII in 1671 and the celebration of the marriagebetween Violante Beatrice of Bavaria and Ferdinandode' Mediciin 1688.45The Bolognesegovernmenttriedto restoreorderaftera 1678 bread riot by using its official print shop to divert attentiontoward age-old public ceremonies- 'because the ancientcustomof this countryrequiresa solemn demonstrationof joy to the BolognesePeople in memoryof the recentcivic disturbances."46 The Milanesegovernment 43Ulvioni, (as n. 27); Fumagalli,Lexicontypographicum idem,Cronologiaet istoriade capie giudicide Saviidella Italiae (Florence1905);C. Santoro,"Tipografimilanesi cittddi Ferrara(Ferrara1683). del secolo XVII," La Bibliofilia 67 (1966) 303-49; GiuseppeVernazza,Dizionariodei tipografideiprincipali 4S Relazionedel'elezionein Re dei Romanidella maestd correttorie intagliatoriche operanonegli Stati Sardidi di LeopoldoRe di Boemia (Florence 1658); Manfredi Terraferma e piiuspecialmentein Piemontesino all'anno Macigni,EsequiedelSerenissimoFerdinandoII granduca 1821 (Turin1859); Mantua,Archiviodi Stato, D'Arco di Toscana(Florence1671);AlessandroSegni,Memorie 224-27: Carlo D'Arco, Notizie delle accademie,dei di viaggi e feste per le reali nozze dei serenissimisposi giornalie delle tipografiechefiorironoin Mantua,vol. 3; ViolanteBeatricedi Bavierae Ferdinando,principe di FrancescoBarbieri,Librie stampatori nellaRomadeipapi Toscana(Florence1688). (Rome 1965); Alfonso Mirto,Stampatori,editori,librai nella secondametddel Seicento(Firenze1984);Albano 46Racconto dellafesta popolaredella Porchetta,fatta in Sorbelli, Storia della stampa a Bologna (Bologna Bolognaquest'anno1678,dedicatedto Gonfaloniereand 1929). Anziani del 4o bimestre (Bologna 1678): "Non tanto perche l'allegrezza pubblica sia stata mai sempre 44 The work in questionwas Antonio Libanori,Ferrara introdotta persollievocomunedellegenti,quantoperche d'oroimbrunito(Ferrara1665-67), printedby Alfonso lo stile antico di questa patria richiede una solenne and GiambattistaMaresti,and reprintedin 1674 when dimostrazionedi gioia al Popolo Bolognesein memoria the Maresti became ducal printers. The others are delle trasandateturbolenzecivili gia estinte nel giorno Alfonso Maresti,Teatrogenealogicoet historicodell'an- 24 agosto,si e celebrataparimentequest'annola consueta tiche et illustrefamiglie di Ferrara(Ferrara1678-81); FestaPopolaredella Porchetta." This content downloaded from 143.239.102.1 on Sat, 16 Nov 2013 06:08:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions POLITICALPUBLISHINGAND ITS CRITICSIN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY 189 had its official printinghouse produce a set of municipalhistoriesby variousauthorsand a treatiseon militaryexpendituresand taxes by local lawyerAmbrogioOppizzone.Moreover, this governmentand that of Piedmonteventuallygave the officialprint shop exclusiverights to publish the local newspaper.And to ensurepropercoverage,Piedmontgave the journalist a 1,000 lire pension.47 The Venetiangovernmentoutdid them all. It had its official printerproduce a complete edition of the works of politicaltheoristTommasoRoccabellafavoringthe Venetianpolitical system.48It had him do official textbooks using the "gloriousdeeds of the Venetianheroes" as lessons for education in rhetoric.49It commissionedhim to publish sixteen orations by GiovanniFrigimelicaRobertiand others in praiseof Nicolo Sagredo,raisedto the dogeship in 1675. And it also had him publish works supportingthe main public policy initiativeof the time, which was the war to stop the occupationof Creteby the OttomanTurks.Accordingly,he supplied narrativesof victorieswhen they occurred,as at Focea (Phocaea)in 1648. And when there was nothing particularlyimportantto report,he supplied informationconcerningthe armada's"happyprogress."50 Eachpamphletsharedthe experiencesof "ourarms" in "ourbattles,"even if the readershad nothing to do with those battles except to help pay for weapons and ships. The Venetiangovernmentthen released,aftersome hesitation,the next state-supported official historiographyafterAndreaMorosini's,that of BattistaNani on the marketin Italian for the formationof popularviews.5'Yet, in carryingout this policy, it did not try to stamp out all alternativeviews. Instead,it seemedto agreeimplicitlywith Pietro GiovanniCapriata, author of an unofficial account that demonstratedthe "unsuccessfulnessof the Venetian forces" trying to recoverthe formerlysubjectisland of Crete after the Ottomaninvasionof 1645. The Senators,noted Capriata,permittedthe distributionin Venice of his alternative account simplybecause "thoseverywise men, in their good judgment,have understoodthat our style, even thoughit inclinestoward. .. the truth,is in no wayaliento the esteem,veneration, and admiration[due to] the majestyof that most augustgovernment."52 The circulation 47Jovane,(as n. 28) 61; Bellocchi, (as no. 26) vol. 2, 3943. culturaveneta,vol. 4, II Seicento,2 parts (Vicenza1973) 1:72-83. 48Iddio operante(Venice 1645); Il principedeliberante "2PietroGiovanniCapriata,Dell'historia,3 vols. (Genoa (Venice 1646); Il principe morale (Venice 1645); Il 1638-52), 2:unpaginatedpreface:"Conmaggiorverita, principepratico(Venice1645). cosi, con rispettomaggiorho i successipoco felici delle Arme Veneziane rappresentati; havendo nelle cose 49 Il vello d'oro, ovvero la retorica veneziana, dove dubbie sempre nella piu benigna interpretazione principalmenteco'pregisingolaridi Venezia,e con molti inclinato. In maniera,che nostre opere sono publicafatti gloriosidegli eroi venezianis'insegnal'artedel ben mente nella stessa citta di Veneziavendute, lette e con parlare(Venice1667). applausinon minoriche altrovericevute,dove quellede' loro scrittori rimanendo affatto sterminate, non soRelazionedella vittoriaottenutadalle armi della Ser. compaionoin luce, e gli autorisono statipuniti,e puniti Repubblicadi Veneziacontrol'armataTurchesca in Asia ancorai capitani, che mal si disportarononei sinistri nel Porto di Focchie, 12 maggio 1649 (Venezia 1649), incontridelle armi,e delle pubblichefattioni. Le quali followed by Continuazione dei felici progressi della cose mi fan credereche quei sapientissimiSignori,col Serenissima Repubblica di Venezia nella Dalmazia loro buon giudizio,habbinoappreso,che il nostrostile, (Venezia1649). benche con tutti ugualmenteamicodellaverita,non sia peropuntoalienodallastima,veneratione,e ammiratione 51 This historiographyis criticizedfor its very vulgarity dellaMaestadi quelAugustissimo governo,il qualedopo by Gino Benzoni, "La storiografia e l'erudizione il Romanofra quanto o si legga o si sappia essersi al storico-antiquario: gli storicimunicipali,"in Storiadella mondo ritrovati,non ha mai avutosuperiore. . ." This content downloaded from 143.239.102.1 on Sat, 16 Nov 2013 06:08:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 190 BRENDANDOOLEY of political information,Capriataimplied,could not be stopped;the best policy was to avoid its worst effects. Once the governmentsfound they could put across their own point of view without damagingthe press as an industry,they began to put their economic policies ahead of their own press regulations.In most of the Italianstates, but especiallyVenice and Naples, governments disassociatedthemselvesfrom repugnantideas printed in their states by permitting the publication of books with false place names." In addition, the Venetian government tacitly allowed booksellers to avoid paying duty and showing the censor'spermission for small packages of books of any kind sent through private mailing addresses.The government of Naples abolished the law requiringthe consignment to the government of a certainnumberof copies of newly printedworks, and that of Tuscanyrelaxed enforcement of the law calling for the delivery of a certain number of free copies to public libraries, both of which were originallydesigned in part to discourageexcessive printing. Moreover, the Tuscan government allowed news sheets to circulate, at least for a time, without any supervisionat all, for the expressed purpose of encouragingthe industry."[First Secretary Andrea] Cioli gave the order," State Auditor Alessandro Vettori later recalled, "to let them print without having them pass through my hands, so they could go out quickly to Rome by the same post from Genoa.""4The behavior of all these governments seemed to suggest that the production of books was no different from the production of any other article. The circulationof all this literaturehelped bring about a majorchangein theories about the communicationof meaningin politics, a changefromwhat mightbe called the monopolist theory of communicationto what could be called the free markettheory.This is not to imply that a wholly free press was in anyone'smind at this point in Europeanhistory.Even Ludovico Antonio Muratori,one of the chief pre-Enlightenmentfigures of the early eighteenth century,supportedsome sort of censorship."The new view simplystated that control was effective up to a point; and beyond that, persuasionand argumentwere necessaryto produce favorableopinion regardingpoliticalobjectives. This changeis first discerniblein the 1670sin the work of NeapolitanjuristGiambattista De Luca. Born in Potenza and educated at the Universityof Naples, he spent most of his careeras a lawyerin Rome,first as a consultantfor privatefamiliesand subsequentlyfor the Spanishmonarchy.Some of this experiencehe distilled in his main work, the eighteen-volume Theatrumveritatiset iustitiae,publishedfrom 1669-81, where he included some 2,500 of his most importantopinions, in a veritableencyclopediaof the jurisprudenceof his day. Then he translatedthe whole work, callingit a compendiumof "civil,canon, feudal and municipal law, moralizedin the Italian language,"explaininghis motives in a disquisitionon "whetherit is a good idea to analyzethe law in the vernacular."He gave the usual reasons againstsuch a practice,based on a notion of a limited public sphere that Sarpiwould have 53 Examplesare in MarinoParenti,Dizionariodei luoghi di stampafalsi, inventati o supposti (Florence 1951), passim. "Unacontroversadisposizionesulle copie d'obbligonel secolo diciassettesimo,"in Studi bibliografici.Atti del convegnostoricosul libroitaliano(Florence1967) 16974. 54MariaAugustaMorelli,Delle primegazzettefiorentine (Florence1963) 6. In addition,ClementinaRotondi,"II S5 Riflessionisoprail buon gusto, in Operedi Ludovico diritto di stampain Toscana,"La Bibliofilia82 (1980) AntonioMuratori, ed. GiorgioFalco andFiorenzoForti 137; Paolo Ulvioni, (as n. 27) 93; Caterina Santoro, (Milan1964)256. This content downloaded from 143.239.102.1 on Sat, 16 Nov 2013 06:08:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions ITALY POLITICALPUBLISHINGAND ITS CRITICSIN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY 191 found most congenial. After all, law was the better part of politics in times of peace, so it could well be consideredone of the arcanaprincipum.56 "If the ignorantmassesshould come to know about the exceptions and the loopholesby which crimescan be excused or contracts and obligationsevaded,"he noted, paraphrasinghis adversaries,"theywould be much better able to commitexcesses or to defraud."Or, worse yet, "everyonemight presumeto play the judge or the counselloror the promoterof causes.""In other words, the legal side of civil society would be taken out of the officialpublic sphereand placed in the privateone. Yet he believed that the necessityof openingup the legalprocessto popularscrutinyfar outweighed all of these counter-arguments.Lawyershad assumedtoo much powerto pervertthe law for their own purposes. "The judges and tribunalsoppress,"he noted, "drawinghearingsout interminablyand making themselvesthe mastersnot only of the propertyin question but even of the liberty of the litigants."58Thus, he took it upon himselfto explain in detail each element of the law and its purpose, for the benefit not only of princes, whom such knowledge would permit to govern better, but also to the litigants themselves, "so they can, as much as possible, escape the tyrannyof lawyers." Far awayfromproverbiallylawyer-infestedRomeand Naples,the juristGiulio Dal Pozzo of the Universityof Padua expressed the same ideas. He addressedhis "civil institutes,"a work claimingto reconcile Romanand Venetianlaw with the commentariesof ancient and modernjurists,to the same audience. "If anyonewonderswhy I have chosen to write in my native language"[Italian,that is, not Venetian],he observed,paraphrasingan argumentof De Luca, "I respondbrieflythat since the laws speakto everyonewho has to obey them, they ought to be understood by everyone.""9He defended his choice on the basis of the government'snecessity to justify its actions before a reasoningpublic. "Whenthe government imposes a gabel, this primarilyregardsthe public utility,"he noted, "becausethe public sustains the armies in time of war or restoresthe treasuryin time of peace. But [such Giambattista De Luca, II dottor volgare, ovvero il compendiodi tutta la legge civile, canonica,feudale, e municipale.. . Moralizzatoin linguaitaliana,first published in Rome, 1673,whichI consultedin the 6-volume edition (Venice1740);herevol. 1, 18: "Importapoco ... l'essersudditipiCu d'unche d'unaltro,maprincipalmente importa,che sianoben governaticon la buonae diligente dellagiustizia,la qualeconservala pace amministrazione civile e la libertadel commercio,dallaqualenasconole ricchezzee la grandezzadell'istessoprincipato...." Informationabout De Luca is found in the entryby Aldo Mazzacane in Dizionario biograficodegli Italiani 38 (1990) 340-47. 56 "5De Luca, vol. 1, 11: "Perchein tal modo venendo in cognizionedel volgoignorantequelleeccezionie cautele, con le quali si possano scusarei delitti, o impugnarei contratti,e obblighi, si renderapiu facile il commettere gli eccessi, ovvero di defraudarequella buona fede, la quale con la naturalesemplicitasi suole adempiredagli idioti. .. ." '8 Ibid., 12: "Saprannocome megliogovernarei popoli a loro soggetti, e rescriverenelle suppliche,e nei ricorsi, come anche conoscere fraudi dei consiglieri, e degli assessori, e l'oppressioni, che si fanno dai Giudici, e Tribunali,eternandole cause,e rendendosipatroninon solo della robba che si litiga, ma della volonta e liberta dei litiganti, mentre cosi non sarannodegni di scusa.... 59 Giulio Dal Pozzo, Le istituzionidellaprudenzacivile, fondatesulle leggi romanee conformatialle leggivenete, nel quale si stabilisceil jus universaledelle genti con dei giurisconsulti,con le massimedei politici, e l'autorita' con riscontrideglistorici.Operapostuma(Venice1697), "Io non scrivo a critici, perci6 non mi premuniscodi alcuno scudo per difendermidalle loro punture.Ma se alcunosi meravigliasseperche scrivonella linguanatia, brevementerispondo,perche le leggi parlandoa tutti, che devonoubbidirle,devonoessereinteseda ogn'uno." I compareDe Luca,Il dottorvolgare,vol. 1, 13:"L'istessa natura, o ragion naturale insegna, che dovendosi obbligare il popolo ad osservare una legge, con sottoporlo al gastigo nella persona e beni, in caso d'inosservanza,debbasaperequel che ha da osservare." Among the first historians to notice Dal Pozzo was Gaetano Cozzi, Repubblicadi Veneziae stati italiani. Politicae giustiziadal secoloXVI al secoloXVIII(Turin 1982) 324. This content downloaded from 143.239.102.1 on Sat, 16 Nov 2013 06:08:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 192 BRENDANDOOLEY things] comprise the utility of privatepersons by consequence,since the Public maintains peace and religion,which are the most preciouscapitalof Man."60Thus, the only good reason for keeping quiet about politics was a purelypracticalone: because public affairs "are infinite"and "not because . . . public affairscannotbe broughtto the attentionalso of him who does not govern."61 Both Dal Pozzo and De Luca supposed that subjectswere not passivebut must be won over by the prince;and the way to do that was by persuadingthem that he acts in their interests. The view of the earlyseventeenthcenturyhad thus changedinto its exact opposite. The public sphere is not where the glories of the prince are representedand sustained.It is the spherewhere the representationsof prince and subjectsare exchangedand occasionallydiscussed and debated.And it is the spherewherethe prince'sactionsareheld up to scrutinyon the basis of the particularbenefit those actions are supposedto bring to the whole state. All of these accomplishmentsof the seventeenthcenturyin the field of communications were summed up not by a seventeenth-centurythinker,althoughhe is often considered as such, but by one of the earlyeighteenth-century,GiambattistaVico. He noticed for the first time that the transformationof ideas about communicationin politics depended on historical and culturalcircumstancesconnectedwith the developmentof each civilization.He did not believe contemporaryevents in Italy or the rest of Europe were unique. A change to more open communicationpracticeshad previouslyoccurredin antiquityduringthe passage from what he called the "heroic"governmentsof the kings of Rome, considered to be divinely ordained and based on the rule of the strongest,to the "human"governmentof the RomanRepublic,basedon reason,benevolence,andequity.A comparisonbetweenthis change and the passagefrom the modernequivalentof "heroic"government,namely,feudal aristocracy,to the beginningsof "human"governmentsin moderntimes yielded one of the fundamentalpatternsin history.In the "heroic"or aristocraticstage, political discoursewas intentionally concealed from the purview of the general populace and kept as a sort of professional monopolyamongthe rulingclass. "Naturallycontinuingto practicereligiouscustoms, they religiouslycontinuedto keep the laws mysteriousand secret (this secrecybeing the soul and life of aristocraticstates)."62Discussing political interests only among themselves,the aristocratsdecided generallyfor the public good because of their privateinterestsas proprietors. In the "human"stage,by contrast,everyonewas requiredto know the law and to judge private utility in relation to the utility of others. "Naturallyopen, generous and magnanimous (being commandedby the multitude, who naturallyunderstandnatural equity) . . . naturallythey went on to makepublic what had been secret."Such had happenedin Europe within recent memory. On the basis of this observationand reasoning,Vico made the closest thing to a policy Dal Pozzo, Le istituzioni, 46: "Quandoil Pubblico impone alcunagabellao cosa simile,questerisguardano principalmentela pubblica utilita, perche il pubblico sostienele armatein tempodi guerra,e risarcisceil Erario in tempo di Pace. Ma comprendonol'utilitadei privati per consequenza,mentreil Pubblico mantienela pace, e la religione, che sono li piu preziosi capitali dell'uomo." 60 61 Ibid., 45: "Non perche non vi fossero altre cose di ragione pubblica, delle quali ne puo aver notitia anco chi non governa,maperchequestesono infinite,bastera stabilirneuna regola universale,che Ragionpubblicae quella,che e utile al Pubblicoprincipalmentee al Privato per consequenza...." 62 TheNewScience,tr.ThomasGoddardBerginandMax HaroldFisch (Ithaca,N.Y. 1968) 350 (hereand below). A broaderdiscussionof the stage theory,which omits the aspects connectedwith communicationbut is still most useful, is found in Leon Pompa, Vico:A Studyof the "NewScience"(Cambridge19902), chapters9-12. This content downloaded from 143.239.102.1 on Sat, 16 Nov 2013 06:08:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions POLITICALPUBLISHINGAND ITS CRITICSIN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY 193 recommendationthat appearsin the generallydetachedNew Science.Afterthe door to popular participationin political discoursehad been opened in the "human"stage of governments and the principles of equity upon which the people naturallyjudged political actions had been establishedas the principlesof government,that door could once againbe closed. Vico shrankfrom sanctioningthe kind of regularpolitical contentiousnessthat was to fascinate Montesquieuabout the Englishsystemor that was to be implied in the press theoryof Neapolitan EnlightenmentjuristGaetanoFilangieri.Filangierimade the press an indispensable part of a modernconstitution,responsiblefor providingthe conduitbetween the public will and political practice.The "tribunalof public opinion,"he argued,was responsiblefor "administeringto the governmentall the possible aids for preservingand extending the good, and all mannerof obstacles in the way of the introductionof evil."63Vico refused to allow actualcontrol over the public sphereto be deliveredinto the privaterealm.And in the "perfect monarchies"that he expected eventuallyto take over in the last stage of history,the monarchwould be ableto foreseewhatequitypopularviewswould assignto particularcourses of action and take whatevercourse most agreedwith that." Since publicitywould therefore no longer be necessary,secrecyin governmentcould safelybe restored. Modest though they were by comparisonwith Enlightenmentconcepts, the new concepts of the public sphere that emergedin the late seventeenthcenturynot only in Italy but elsewherein Europestronglyinfluencedthe changingexpectationsthat orderedthe political choices of elites in charge,even when power was not seriouslychallenged.And the goals of state building came to be redefinedin terms of what could actuallybe accomplishedas the mandate to rule moved from the realm of symbolismto the realm of persuasion.Indeed, changingnotions about the possibilitiesof coordinatingaction and reachingunderstanding by printed expressions provided one of the practicalbases upon which a social science of politics could be based, and they convergedin the ideas of John Locke and PierreBayle.So, if the history of earlymodernpolitical thoughtis to be writtennow with due attentionto its linguisticaspects,as recentstudiespromise,the thirddimensionin the communicationsrevolution needs to be regardedas a major currentin early modern Europe and brought ever more sharplyinto focus. Illuministi italiani, ed. Franco Venturi,Riformatori napoletani(Milan-Naples1962) 749-50. 63 64 TheNew Science,351. This content downloaded from 143.239.102.1 on Sat, 16 Nov 2013 06:08:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

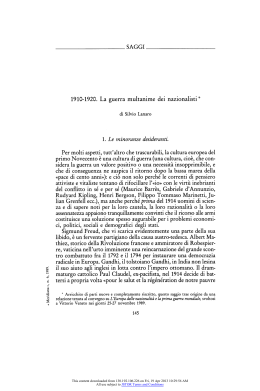

Scarica