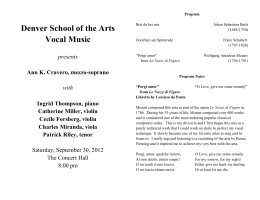

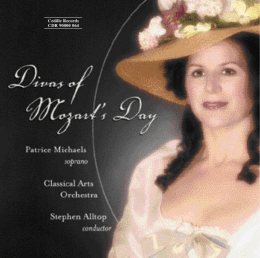

476 5949 Sara Macliver MOZART ARIAS TASMANIAN SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEBASTIAN LANG-LESSING WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART 1756-1791 1 Non curo l’affetto (I have no interest in the affections of a timid lover), KV74b 4’39 2 Vorrei spiegarvi, oh Dio! (O Heaven! I wish I could tell you), KV418 7’12 3 Ruhe sanft, mein holdes Leben (Rest gently, my dear one) from Zaide, KV344 6’42 4 Overture from Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute), KV620 7’01 5 Ach, ich fühl’s (Alas, I feel it) from Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute), KV620 4’17 6 Schon lacht der holde Frühling (See how fair Spring is laughing), KV580 7’35 9 Giunse alfin il momento…Deh vieni non tardar (At last the moment is coming…Ah, do not delay) from Le nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro), KV492 0 Batti, batti, o bel Masetto (Beat me, O handsome Masetto) from Don Giovanni, KV527 3’42 ! Porgi amor (O Love, give me some remedy) from Le nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro), KV492 7 Durch Zärtlichkeit (Through tenderness) from Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio), KV384 8 Overture from Don Giovanni, KV527 3’24 3’55 @ E Susanna non vien!...Dove sono i bei momenti (And Susanna’s not here!... Where are the beautiful moments) from Le nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro), KV492 6’21 Total Playing Time Sara Macliver soprano Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra Sebastian Lang-Lessing conductor 2 4’40 3 6’34 66’25 The plot of Zaide is loosely similar to the later, greater Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio) – indeed, its full description is ‘A Singspiel with libretto by Schachtner after F.J. Sebastiani’s “Das Serail”’. The path of love, at least on stage, is more difficult when it crosses over east and west. Zaide may have faded into the unused pages of the Köchel catalogue were it not for one beautiful aria, Ruhe sanft, mein holdes Leben. The heroine of the title sings this rapturously sweet music over the sleeping body of the man she loves – it is an adult lullaby. Jane Glover notes the prominent use of the oboe, an instrument she believes Mozart associated with seduction, for it appears remarkably often in such a context. She also draws a parallel with the aria’s demands for an exquisite, secure, silvery top to the voice, mixed with an ability to project the text, and the fact that these characteristics are strongly associated with the vocal style of Aloysia Weber – surely she was still on the composer’s mind? Salzburg court poet, trumpeter and friend of the Mozart family Johann Andreas Schachtner recorded how, in a rather inauspicious beginning for a collaborative partnership, his instrument had terrified the infant composer. ‘Merely to hold a trumpet in front of him was like aiming a loaded pistol at his heart.’ Fortunately for posterity, the family friendship survived these early hiccups and in 1780 the grownup Mozart and Schachtner began work on Zaide, KV344, a Singspiel or comic opera with spoken dialogue. They seem to have had no set performers or occasion in mind, and the work was never finished; only 15 numbers are extant. (Luciano Berio and Chaya Czernowin are but two of the more recent composers to attempt some sort of conclusion.) At the time of composing, Mozart was only just back home in Salzburg after a long journey which had encompassed much sadness: the death of his mother, who was his travelling companion, and the end of his infatuation with the noted young singer Aloysia Weber. On this tour he had also encountered Georg Benda’s melodramas, featuring spoken German dialogue with musical accompaniment. Mozart seems to have used this device only in Zaide, so the connection appears relevant. In many of the extant numbers, Mozart tried out for the first time several new things which would appear in his later works, including writing ‘serious’ sung music in German. (Previous works of this calibre had all been in Italian.) Aloysia and the oboe feature again in Vorrei spiegarvi, oh Dio, KV418. It was written in June 1783, by which time life had moved along for Mozart – he was living in Vienna, becoming part of the entrenched musical scene there, happily married to Aloysia’s younger sister Constanze, and expecting the imminent arrival of their first child. (Wolfgang remained good friends with Aloysia and her husband Josef Lange.) 4 Further mystery surrounds Schon lacht der holde Frühling, KV580. Historical convention (though no conclusive documentary evidence) associates it with Josepha Hofer, youngest of the Weber sisters and therefore Mozart’s sisterin-law. The style of the vocal line would have suited her, with its high tessitura and demanding coloratura. (Josepha would become a renowned Queen of the Night in Die Zauberflöte.) More expressive drama emerges in the softer, slower sections, reminding us that all the singing Weber women were praised to some extent for their acting abilities. Around September 1789, the presumed date of composition, Josepha was the prima donna soprano at the Theater auf der Wieden in Vienna. The theory surrounding Schon lacht der holde Frühling is that Josepha had requested a replacement aria for a performance of Paisiello’s Barber of Seville, although any trace of such a performance has been lost. The manuscript score is incomplete (the inner parts are missing) but Mozart did not as a rule record mere fragments in his own list of works, so we assume that what we have is a true record of the complete aria as it was intended, and not merely a draft. Aloysia was shortly to appear at the Burgtheater in Anfossi’s Il curioso indiscreto (Unwise Curiosity). In keeping with the custom of the time she turned to Mozart to write two new arias suited to her, which could be inserted into the existing work, either in place of or in addition to the scheduled items. No, no, che non sei capace, KV419 is rarely if ever heard now and is not included here, but Vorrei spiegarvi was an immediate success, with its delightful contrasts between passages of delicious softness and heartstopping agility. The librettist is unknown, but the text is similar to many such arias of the time and may have been constructed by Mozart himself, or indeed even Aloysia. Little is known about the circumstances surrounding the composition and premiere of Non curo l’affetto, KV74b. The text is drawn from Metastasio’s Demofoonte, where it is given to the character of Creusa, Princess of Phrygia, who is trying to incite a callow young suitor to kill his own brother, whom she believes to have insulted her. This aria was most likely written in early 1771, although some place it still earlier, perhaps for a concert performance in Milan in March 1770. Both in date of composition and in style it sits comfortably alongside its contemporary, the opera seria Mitridate, and is intent on showing off the singer’s coloratura. The teenage Mozart was astonishingly young to be creating something of such confident style. Paisiello’s Barber was immensely popular in Vienna. The libretto was drawn from the play by Beaumarchais, and is of course the first instalment in the adventures of the barber Figaro; it is better known to modern audiences through Rossini’s version. When in 1786 Mozart 5 was looking for a new opera text, he and Lorenzo Da Ponte gleefully chose to capitalise on the public interest in Paisiello’s success, and adapted Beaumarchais’ second tale of Figaro. Le nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro) was something of a risk, given the ‘upstairs/downstairs’ tension of the plot and the growing social unrest across Europe – indeed the play had been banned for some years in Vienna and Paris – but it was a risk which paid off. Part of the success may have been the inclusion of many of the same cast members who had appeared in the Paisiello forerunner, though not always in the equivalent role. requires an excellent sense of line and considerable acting ability to make it really successful, as Susanna is playing a duplicitous game. She and her mistress the Countess are colluding to punish the Count for his wandering eye, and she is in theory singing to him; however she is well aware that her fiancé Figaro is hiding within earshot, and wishes to have a bit of a dig at him for his lack of trust. The ambiguity of her song has been subject to many different directorial interpretations as a result. The Countess, on the other hand, is a more straightforward character. Mozart and Da Ponte were clever in their adaptation of the play: in the opera, the Countess appears rather late into the work, but with her stunning, heartbreaking aria Porgi amor is instantly introduced to the audience and to their sympathies. Everything about her situation is made clear. The feisty Rosina of The Barber of Seville has become a haunted, nervy woman made desperate by her husband’s frequent betrayals. (It’s not clear to what extent ‘Droit de Seigneur’, or the unwritten right of the local lord to have first pick of any girl who caught his eye, was actually practised in Europe, but in cosmopolitan areas its more metaphorical implications of power and status would have been understood in the context of the performance.) Nancy Storace, a dear friend of Mozart’s, was the 21-year-old prima donna who undertook to create Susanna. She and her character seem to have shared many of the same qualities of intelligence, wit and generosity. Indeed the whole opera is notable for the sympathetic portrayal of women, which was not always the case at the time. Susanna was considered the principal role, as she appears more often; in modern times there has been a slight tendency to focus on the Countess, perhaps due to the more lyrical beauty of her music or even a certain lingering snobbishness. Susanna’s major aria Giunse alfin il momento…Deh vieni non tardar is superficially simple, demanding a good middle to the voice but no pyrotechnics. However it The Countess reaches a dramatic peak not in a moment of high, loud coloratura, but in a 6 training) was a good friend of the ultimate reallife ladies’ man, Casanova. Indeed, Casanova attended the premiere performance in Prague on 29 October 1787. particularly solemn recitative E Susanna non vien!. Here she soliloquises on her unhappy situation, culminating in the acknowledgement that she has had to resort to the humiliation of asking her maid, a mere servant, for help. This is the stuff of social revolution. Dove sono i bei momenti, the aria which immediately follows, is justly famed for its emotional intensity. Mozart and Da Ponte brought opera buffa to a new height. Their works combined comedy and tragedy in a deeply satisfying and even revolutionary way. And as with Figaro, the women in Don Giovanni are for the most part portrayed sensitively and as people of intelligence, although this is more dependent on the director than in the earlier work. A case in point is Zerlina’s clever handling of her jealous boyfriend Masetto – Batti, batti is her response to his anger over her perceived infidelity with the Don. Although the text seems violent, the music is all cajoling softness, and no one can doubt she will win him round without too many tears. Figaro was hugely successful at Vienna’s Burgtheater, and was then presented in Prague in January 1787. Mozart himself described the local reaction best: ‘Nothing is played, sung or whistled but Figaro. No opera is drawing like Figaro. Nothing, nothing but Figaro. Certainly a great honour for me!’ Such overwhelming acclamation led Pasquale Bondini, director of the Prague National Theatre, to ask eagerly for a new opera from the Mozart/Da Ponte team. His wife Caterina had played Susanna, so it is no surprise that the new opera, Don Giovanni, also contained a very suitable role for her: the peasant girl Zerlina, who attracts the passing interest of the Don. Mozart’s instinctive understanding of how to use music to enforce dramatic tension is demonstrated in the opening sections of Don Giovanni. The gripping Overture, and the following introduction and duet all hover relentlessly around D major and minor and the related keys of F and B flat. Because the music is corralled in this one tonal area, listeners become as trapped as the characters themselves, and (probably subconsciously) as keen for some sort of resolution. Da Ponte collaborated with Mozart on three of his finest operas: Le nozze di Figaro, Così fan tutte and Don Giovanni. The parallels between the womanising Don Juan and the faithless Count Almaviva of Figaro will be obvious, and as infidelity is a major theme of Così too, it becomes even more fascinating to learn that Da Ponte (himself no saint despite his seminary This exceptional feeling for the interaction of music and drama had been apparent even in 7 such early works as Zaide, where Mozart had considerable input into Schachtner’s text. But it was with his ‘other’ east/west opera, Die Entführung aus dem Serail, that he really had the chance to participate fully in shaping all aspects of an opera. He wrote with immense satisfaction to his father, noting that he was working very happily with Gottlieb Stephanie on the plot and words: ‘[He] is arranging [Bretzner’s] libretto for me just as I want it.’ Stephanie was the director of the German National Theatre, controlled by the Viennese court. He and Mozart began work together in 1781, when the young composer was lodging with the Weber family and developing a growing interest in Constanze, a daughter of the house. Letters to his stern father tended to focus on strictly musical matters. the style of the later Susanna and Zerlina, and for the premiere performances was sung by Therese Teyber, who would eventually perform all these roles to great acclaim. The womanly strength of these heroines found a new incarnation in the gentle, well-brought-up Pamina, central figure in Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute). This Singspiel was in so many ways a new departure for Mozart. It was the result of an intense collaboration between himself and his friend Schikaneder, who by this time (1791) had established his own performing company in Vienna. An all-round theatre professional – he was an acclaimed serious Shakespearian as well as comic actor and writer – Schikaneder knew how to attract a house, and filled his productions with fabulous costumes, special effects, live animals and so on. His troupe included many of Mozart’s favourite singers, including his sister-in-law Josepha. The story of Die Entführung concerns the heroine, also named Constanze, who is held prisoner in a harem by the Pasha Selim, who adores her and hopes she’ll come round to adoring him. She pines for her lover, Belmonte, who attempts to rescue her and fails; but the Pasha magnanimously gives the pair their freedom. Constanze’s maid Blonde also has to fight on several fronts, warding off the attentions of the harem overseer Osmin and encouraging those of Belmonte’s manservant Pedrillo. Durch Zärtlichkeit is Blonde’s dismissal of Osmin, where she soars far above him in every respect. She is a character very much in The two men were Masons, and Masonic symbolism abounds throughout the opera. But unusually (though as we have seen, characteristically of Mozart) there is little of the rank chauvinism that permeated the Masonic societies of the day. Once again Mozart gives us intelligent, multi-dimensional female characters; and his men, too, are not the cardboard stereotypes that could easily have invaded what on one level is a mere ‘rescue opera’. Prince Tamino is sent by the Queen of the Night to 8 this. Within a year of being widowed, she had single-handedly got herself and her two young sons out of debt and onto some sort of firmer domestic footing. Could her personality lurk unseen behind many of the characters presented in this diverse recording? rescue her daughter Pamina from the clutches of Sarastro; however, the young couple (who have fallen in love at first sight) find they respect the older man and Tamino applies to join his order. He must pass through three trials in order to be accepted and to move on to a happy life with Pamina. (The whole plot is riddled with ‘three’ symbolism, as indeed is the Overture, with its striking three-chord opening.) His companion Papageno, a birdcatcher, seeks only a bride and a quiet life. Three ladies, three boys and a menacing slave called Monostatos also play their parts in the drama. Yet much of the most sincere emotion rests in Pamina. Mozart’s first Pamina was Anna Gottlieb, a mere 17 years old, and of the appropriate beauty and innocence to make a huge impact in this role. Unaware that Tamino has taken a vow of silence as part of his initiation, Pamina is utterly desolate when, at what should be a joyous reunion, he refuses to speak to her. Her soliloquy Ach, ich fühl’s is a short, quiet, absolute showstopper. Elisabeth Söderström once suggested in a memorable insight that the pulsing accompaniment should imply a heartbeat, beneath a vocal line that pours straight from the soul. K.P. Kemp Mozart’s heroines tended to be intelligent and brave, and where possible tried hard to be virtuous as well. As so little is definitely known of the true character of his wife Constanze, it is tempting to assume she was at least a little like 9 Creusa: Zaide: 1 Non curo l’affetto I have no interest in the affections of a timid lover who holds so little valour in his breast, who trembles if he must use a sword, who is bold only when the talk is of love. d’un timido amante che serba nel petto si poco valor, che trema se deve far uso del brando, che audace è sol quando si parla d’amor. 3 Ruhe sanft, mein holdes Leben, Rest gently, my dear one, sleep till your happiness awakens. Look, I’ll give you a picture of myself: see how it smiles at you like a friend! You sweet dreams, rock him to sleep and may the delights of his dreams finally bloom into ripe reality. schlafe, bis dein Glück erwacht; da, mein Bild will ich dir geben, schau, wie freundlich es dir lacht! Ihr süssen Träume, wiegt ihn ein und lasset seinem Wunsch am Ende die wollustreichen Gegenstände zu reifer Wirklichkeit gedeihn. Pietro Metastasio Johann Andreas Schachtner, after Franz Josef Sebastiani Clorinda: 2 Vorrei spiegarvi, oh Dio! qual è l’affanno mio; ma mi condanna il fato a piangere e tacer. Arder non può il mio core per chi vorrebbe amore e fa che cruda io sembri un barbaro dover. O heaven! I wish I could tell you what I am suffering, but fate condemns me to suffer in silence. My heart cannot burn for the man who seeks my love and cruel duty makes me seem heartless. Ah conte, partite, correte, fuggite lontano da me. La vostra diletta Emilia v’aspetta, languir non la fate, è degna d’amor. Ah stelle spietate! nemiche mi siete. (Mi perdo s’ei resta, oh Dio!) Partite, correte, d’amor non parlate, è vostro il suo cor. Ah, Count, leave me, run, fly far from me. Your beloved Emilia is waiting for you; don’t make her suffer, she is worthy of love. O pitiless stars! you are my enemies. (If he stays, I am lost, O heaven!) Go, run from me, do not speak of love; her heart belongs to you. Pamina: 5 Ach, ich fühl’s, es ist verschwunden, Alas, I feel it – it has vanished, love’s happiness is gone forever. Those hours of gladness will never return to my heart. Tamino, look: these tears are flowing for you alone, beloved. If you do not feel love’s longing, then I will find my peace in death. ewig hin der Liebe Glück! Nimmer kommt ihr, Wonnestunden, meinem Herzen mehr zurück. Sieh, Tamino, diese Thränen fliessen, Trauter, dir allein. Fühlst du nicht der Liebe Sehnen, so wird Ruh’ im Tode sein. Emanuel Schikaneder 6 Schon lacht der holde Frühling auf blumenreichen Matten, wo sich Zephire gatten unter geselligem Scherze. See how fair Spring is laughing over the meadows rich with flowers, where the breezes come together in playful company. Wenn auch auf allen Zweigen sich junge Blüten zeigen, kehrt doch kein leiser Trost in dieses arme Herz. But though on every branch the flowers are budding, no soft words of comfort return to this poor heart. Anonymous 10 11 Da sitze ich und weine einsam auf der Flur, nicht um mein verlornes Schäfchen, nein, um den Schäfer Lindor nur. Anonymous I sit here and weep, alone in the fields, not for my lost lamb, no, only for the shepherd, Lindor. quì ridono i fioretti, e l’erba è fresca, ai piaceri d’amor quì tutto adesca. Vieni ben mio, tra queste piante ascose, vieni, vieni, ti vo’ la fronte incoronar di rose. here the little flowers laugh, and the grass is fresh, everything is here at love’s service. Come, my love, here in the concealing shadows of this grove I long to crown your head with roses. Lorenzo Da Ponte after Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais Blonde: 7 Durch Zärtlichkeit und Schmeicheln, Gefälligkeit und Scherzen, erobert man die Herzen der guten Mädchen leicht. Doch mürrisches Befehlen, und poltern, zanken, plagen, macht, dass in wenig Tagen so Lieb’ und Treu entweicht. Through tenderness and flattery, courtesy and pleasantries, one easily conquers the heart of a good maiden. But surly orders and blustering, scolding, pestering – in only a few days they’ll make love and faithfulness drain away. Christoph Friedrich Bretzner Susanna: 9 Giunse alfin il momento che godrò senz’affanno in braccio all’idol mio. Timide cure, uscite dal mio petto, a turbar non venite il mio diletto! Oh come par che all’amoroso foco l’amenità del loco, la terra e il ciel risponda, come la notte i furti miei seconda! At last the moment is coming when I shall lie in the arms of my beloved in delight, free from anxiety. Timid thoughts, begone from my breast, do not come to spoil my joy! Oh, how it seems that these lovely surrounds, heaven and earth in their beauty, respond to the flame of my passion, just as the night furthers my ruses! Deh vieni non tardar, o gioja bella, vieni ove amore per goder t’appella, finchè non splende in ciel notturna face, finchè l’aria è ancor bruna, e il mondo tace. Quì mormora il ruscel, quì scherza l’aura, che col dolce sussurro il cor ristaura, Ah, do not delay, fair joy, love summons you to pleasure; answer his call, until the shining moon has set till the sky lightens again, and the world falls silent. Here the murmuring brook, the playful breezes heal the heart with their sweet whispering; 12 Zerlina: 0 Batti, batti, o bel Masetto, Beat me, handsome Masetto, beat your poor Zerlina: I will stand here like a little lamb, waiting for your blows. I will let you strike my head, I will let you tear out my eyes, and then I will gladly kiss your dear little hands. Ah! I see, you don’t have the heart. Hush, hush, my beloved, let’s spend our time in gladness and joy, both night and day, yes, night and day. la tua povera Zerlina: starò quì come agnellina le tue botte ad aspettar. Lascierò straziarmi il crine, lascierò cavarmi gli occhi, e le care tue manine lieta poi saprò baciar. Ah! lo vedo, non hai core. Pace, pace, o vita mia, in contento ed allegria notte e dì vogliam passar, si, si, notte e dì vogliam passar. Lorenzo Da Ponte The Countess: ! Porgi amor qualche ristoro O Love, give me some remedy for my suffering and my sighs! Either give me back my beloved, or let me die. al mio duolo, a miei sospir! O mi rendi il mio tesoro, o mo lascia almen morir. Lorenzo Da Ponte after Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais 13 The Countess: @ E Susanna non vien! Sono ansiosa di saper come il conte accolse la proposta. Alquanto ardito il progetto mi par, ad uno sposo sì vivace e geloso! Ma che mal c’è? Cangiando i miei vestiti con quelle di Susanna, ei suoi co’ miei a favor della notte – oh cielo! A qual’ umil stato fatale io son ridotta da un consorte crudel! Che dopo avermi con un misto inaudito d’infedeltà, di gelosia, di sdegno! prima amata, indi offesa e alfin tradita fammi or cercar da una mia serva aita! And Susanna’s not here! I’m anxious to know how the count took the proposal. The plan seems rather rash to me, and with a husband so edgy and jealous! But where’s the harm? Switching clothes with Susanna, and she with me under cover of darkness… O heavens! See what a sorry, wretched state I am reduced to by a cruel spouse! With an unheard-of mixture of infidelity, jealousy and scorn he first loved me, then insulted me, and finally betrayed me and now here I am forced to turn to a servant for help! Dove sono i bei momenti di dolcezza e di piacer, dove andoro i giuramenti di quel labbro menzogner! Perchè mai, se i pianti e in pene Where are the beautiful moments of sweetness and pleasure, where did the promises go, that came from those lying lips? For me everything has turned per me tutto si cangiò, la memoria di quel bene dal mio sen non trapassò? to pain and weeping – why then does the memory of that bliss still linger in my breast? Ah! se almen la mia costanza nel languire amando ognor mi portasse una speranza di cangiar l’ingrato cor. Ah! if only my constancy in fainting for love of him even now could bring me hope of changing his ungrateful heart! Lorenzo Da Ponte after Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais Translations by Natalie Shea 14 15 Sara Macliver Recent engagements have included the roles of Aphrodite and The Thracian Woman in the world premiere of Richard Mills’ opera For the Love of the Nightingale (2007 Perth Festival), Mozart’s Mass in C minor (West Australian Symphony Orchestra and Australian Chamber Orchestra), Mozart’s Betulia Liberata (University of Western Australia), Mozart arias, Mendelssohn’s Lobgesang and Mahler’s Symphony No. 4 (Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra), Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 Resurrection (The Queensland Orchestra), Orff’s Carmina burana (Adelaide Symphony Orchestra), a recital at the Perth Concert Hall and J.S. Bach’s St Matthew Passion (Sydney Chamber Choir and Sydney Philharmonia Choirs). Sara Macliver is one of Australia’s most popular and versatile artists, appearing in opera, concert and recital performances and on numerous recordings. She is regarded as one of the leading exponents of Baroque repertoire in Australia. Sara Macliver trained in Perth with Molly McGurk. She was a Young Artist with West Australian Opera in 1996 and her roles for the company have included Micaela (Carmen), Pamina and Papagena (The Magic Flute), Giannetta (The Elixir of Love), Morgana (Alcina), Ida (Die Fledermaus), Nannetta (Falstaff), Vespetta (Pimpinone) and Angelica (Orlando). Sara Macliver is a regular performer with the West Australian, Melbourne, Sydney, Adelaide and Tasmanian Symphony Orchestras and The Queensland Orchestra, as well as Musica Viva Australia, Melbourne Chorale, Australian Chamber Orchestra, Australian Bach Ensemble, Australian Brandenburg Orchestra and Sydney Philharmonia Choirs among others. Career highlights have included a performance in the presence of Diana, Princess of Wales, a recital concert in Japan, a five-city tour of Italy with Ola Rudner and the Haydn Orchestra, Mahler’s Symphony No. 4 with Edo de Waart and the Sydney Symphony, and a program based on the life of Jane Austen, with pianist Bernadette Balkus for Musica Viva. She also appeared in Pinchgut Opera’s productions of Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo and Purcell’s The Fairy Queen to great critical acclaim. Sara Macliver’s recordings for ABC Classics include Fauré’s Requiem and The Birth of Venus, Carmina burana, and a CD of Haydn arias with the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra and Ola Rudner. She is featured in the joint ABC Classics–ABC Television production of Handel’s Messiah, which has screened several times on national television as well as being available on CD and DVD. She has released two discs of duets with mezzo-soprano Sally-Anne Russell: Bach Arias and Duets, nominated for an ARIA Award in 2004, and Baroque Duets (including the Pergolesi Stabat Mater), winner of the ABC Classic FM Listener’s Choice Award in 2005. Her recording of Canteloube’s Songs of the Auvergne was released on ABC Classics in 2006. 16 released numerous CDs with the TSO on ABC Classics, including a complete set of the Schumann symphonies, a disc of Romantic overtures, and music for piano and orchestra by Saint-Saëns and Franck with Duncan Gifford. His discography also includes the world premiere recording of the complete symphonies of Guy Ropartz. Sebastian Lang-Lessing Sebastian Lang-Lessing is Chief Conductor and Artistic Director of the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra. He was Music Director of the Orchestre Symphonique de Nancy from 1999 to 2006. He served for eight years as Conductor in Residence at Deutsche Oper Berlin at the invitation of Götz Friedrich, and his relationship with that company enabled him to build a wide repertoire and work with internationally renowned singers and stage directors. As music director of Opéra National de Nancy, he has conducted Tristan und Isolde, Tannhäuser, The Flying Dutchman, Der Rosenkavalier, Arabella, Fidelio, Der Freischütz, Wozzeck, Jenůfa, Peter Grimes, Carmen, Manon Lescaut, The Tales of Hoffmann, Simon Boccanegra, Don Giovanni and The Magic Flute. In 2006 the French Government recognised his work with Orchestre Symphonique de Nancy and Opéra de Nancy by awarding it national status. Sebastian Lang-Lessing studied conducting at the Hamburg State Conservatory. After being awarded the Ferenc Fricsay Prize in Berlin he worked as assistant conductor at Hamburg State Opera then as First Kapellmeister at Rostock Opera. His international career began in Paris at the Opéra Bastille. In 1997 he made his American debut at Houston Grand Opera; recent engagements with the company have included performances of Carmen and Faust. He has also appeared with San Franciso Opera and Los Angeles Opera. In Europe he has worked regularly at opera houses including Oslo Opera, Hamburg State Opera and Stockholm Royal Opera. In addition to concerts around Tasmania, Sebastian Lang-Lessing directs an annual Sydney Season with the TSO at City Recital Hall Angel Place and has led the orchestra on a tour of Japan as part of Asia Orchestra Week. He also initiated a series of performances at the Port Arthur Historic Site in 2006. Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra Established in 1948, the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra is acclaimed as one of the world’s finest small orchestras. Resident in the purposebuilt Federation Concert Hall, Hobart, the TSO Sebastian Lang-Lessing is also active as a conductor of symphonic repertoire, and has led major orchestras all over the world. He has 17 In 2003 the orchestra launched its Australian Music Program under the direction of Richard Mills. Since then the TSO has released eleven titles and recorded a further five discs as part of the TSO’s Australian Composer Series on ABC Classics. presents more than 60 diverse concerts across Tasmania and mainland Australia each year. German-born Sebastian Lang-Lessing has been the orchestra’s Chief Conductor and Artistic Director since 2004. With a full-time complement of 47 musicians, the TSO’s core repertoire is the music of the Classical and early Romantic periods. It is, however, a versatile orchestra, equally at home in jazz, popular music and light classics, and recognised internationally as a champion of Australian music. Recorded 8-11 March 2006 in Federation Concert Hall, Hobart. Executive Producers Robert Patterson, Lyle Chan Recording Producer Brooke Green Recording Engineer Veronika Vincze Mastering Virginia Read Editorial and Production Manager Hilary Shrubb Publications Editor Natalie Shea Booklet Design Imagecorp Pty Ltd Cover Image Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1781-1841) The Palace of the Queen of the Night – set design for an 1816 Berlin production of The Magic Flute. All photographs of Sara Macliver by Frances Andrijich. ABC Classics thanks Alexandra Alewood and Melissa Kennedy. 2007 Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 2007 Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Distributed in Australia and New Zealand by Universal Music Group, under exclusive licence. Made in Australia. All rights of the owner of copyright reserved. Any copying, renting, lending, diffusion, public performance or broadcast of this record without the authority of the copyright owner is prohibited. For the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra Managing Director Nicholas Heyward Manager, Artistic Planning Simon Rogers Orchestra Management Mariese Shallard www.tso.com.au The TSO presents annual subscription seasons in Hobart and Launceston, and since its inception has regularly toured regional Tasmania and mainland Australia. The orchestra appears at major Australian arts festivals and in 2005 initiated an annual Sydney Season. International touring has seen the TSO in North and South America, Greece, Israel, South Korea, China, Japan and Indonesia. The TSO regularly records for radio, CD, film and television. Its recordings on international and Australian CD labels have garnered critical praise, and the TSO is the only Australian orchestra to have released a complete set of the Beethoven symphonies, conducted by David Porcelijn, and a complete cycle of Schumann symphonies, conducted by Sebastian Lang-Lessing. 18 19

Scaricare