Law Libraries in Italy

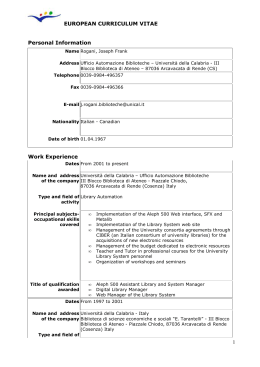

Rosa Maiello

Central Library

University “Parthenope” of Naples, Italy

Meeting: 136:

Law Libraries

WORLD LIBRARY AND INFORMATION CONGRESS: 75TH IFLA GENERAL CONFERENCE AND COUNCIL

23-27 AUGUST 2009, MILAN, ITALY

http://www.ifla.org/annual-conference/ifla75/index.htm

Theme: “The Italian legal system, basics and new trends”

Abstract

People have always the opportunity to use the results of the work of the italian law libraries.

Thanks to libraries,many works are retrievable through OPACs, the texts of legislations and

regulations are freely available in digital format, while professional librarians ensure accuracy,

reliability and delivery of legal information. There are many law libraries in Italy, with prestigious

collections and advanced reference services, continuously update. Some libraries are involved in

projects for the digitization of their historical collections, and/or in institutional publishing

projects, others cooperate to share resources, competencies and services. Some of their activities

are on a voluntary basis. Librarians are in the forefront in promoting free availability of italian

government information on the net and the open access to the results of scientific research.

However, law libraries and librarians in Italy are in some respects a ‘hidden’ resource, and the

important and well-known libraries of the two branches of the italian Parliament - Biblioteca del

Senato della Repubblica and Biblioteca della Camera dei deputati - are in this sense a laudable

exception. In facts, law libraries in Italy operate in a fragmented context: there is not a general

network or coordination between governmental (at national, regional and local level), university

and community libraries, and there are few programs aimed to train specialist librarians.

From the 90s of the twentieth century, certain factors are significantly affecting methods of

production, interpretation and application of law, as well as they are causing significant changes

in the needs and expectations of users: technological development, digital convergence,

internationalization, european and national policies to foster active citizenship and social

inclusion. These changes are gradually bringing the focus on libraries and their approach to

integration of contents and transfer of knowledge.

This paper will explain the characteristics and trends of the Italian law libraries in their social,

regulatory and institutional environment, and in their relations with the other important players in

the field of legal information, documentation and publishing.

1. Introduction1

Let me thank Professor Knudsen and the IFLA Law Libraries Section for giving me the opportunity

to speak about law libraries in Italy. I am especially honored of this, since for the first time this

topic is addressed in its entirety.

1

All cited web pages were last checked on August 18, 2009.

There are many law libraries in Italy, with prestigious collections and advanced services. They are

often at the forefront in initiatives aiming to ensure accuracy, reliability and availability of legal

information and documentation, but are in some respects a ‘hidden’ resource, because operate in a

fragmented context.2 Since 1861 (date of the unification of Italy as nation-state), the Italian

government has been characterized by a tension never fully resolved between centralism and

localism, which even in the fields of legal information policies and knowledge institutions has

slowed the integration and the development of service-oriented strategies. However, this situation is

changing: in the nineties of the twentieth century, began a period of reforms designed to promote

cooperation and innovation, simplify legislation and bureaucracy, empower the role and

responsibility of Regions and local bodies, and enforce citizens rights.3 Financial pressure,

technological development, digital convergence, internationalization, European policies for a

common market in the framework of knowledge economy, are the most important drivers of of the

change, which is gradually bringing the focus on libraries as catalyzers and producers of knowledge

and development.

After a general overview of the Italian policies and market of legal information, we shall see the

organization and activities of the Italian law libraries, and some brief notes on the state-of art of law

librarianship. Finally, we shall try to draw some conclusions about the perspectives of the national

law library system in the hybrid and digital environment.

2. Legal information: policies and market

The Italian legislation on information rights and policy is scattered in many sources, produced at

different times and with different purposes, such as: digital administration and eGovernment,

cultural heritage, copyright protection, education and research. These rules are not completely

harmonized each other, and this leads to some antinomies and / or failures in implementation.

Legal documentation produced by public bodies

All public bodies are required by law4 to ensure the availability, management, access, transmission,

storage and accessibility of information in digital mode and to organize themselves and act for this

purpose by using appropriate information and communication technologies. The law also provides

2

See Paolo TRANIELLO, Storia delle biblioteche in Italia. Dall’Unità ad oggi. Bologna, Il Mulino, 2002.

See Franco BASSANINI and Luca CASTELLI, Semplificare l’italia. Bagno a Ripoli (Florence), Passigli, 2008.

4

Legislative Decree 7th March 2005, n. 82, consolidated version (2006),

http://www.cnipa.gov.it/site/_files/Codice%20Amministrazione%20Digitale_02.pdf. See also the Decree of the

President of the Italian Republic 28th December 2000, n. 445,

http://www.parlamento.it/parlam/leggi/deleghe/00443dla.htm.

3

2

rules for authentication and preservation of digital documents. Another law protects the right of

access of disabled people to public services, and requires the institutions to ensure that their web

sites are complying with the standards regarding technological accessibility.5

Actually, while many public bodies publish on their own sites at least the norms and/or the general

decisions they produce, there is no guarantee about the authenticity of these texts, nor about the

permanency of their URLs, nor about the availability of their consolidated versions.

The ‘official’ texts of legislation and other public acts are only those published in the Italian

Official Journal, Gazzetta ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana,6 whose online version is freely

available only for last 60 days: all the rest is fee. Its publisher is a company7 that, while not having

the copyright on the official acts of public bodies - because they are on public domain, according to

paragraph 5 of the Italian Copyright Law, -8 is the copyright holder of the database. According to

paragraphs 11 (copyright on works published in the name of State or local authorities) and 102-bis

(database protection) of the Copyright Law, the fact that this company has as unique shareholder the

Italian Ministry of Economy implies that the Ministry of Economy is the copyright holder of the

database, but does not imply that this database should be free. Moreover, the Official Journal

database system is not compliant with the requirements for technological accessibility and

interoperability.

However, since 1999, there is a national project aiming to standardization of classification and

marking of legal documents in digital format, and to integration of all public bodies activities on

this matter to facilitate the public and free access, as well as the policy-makers activities for the

simplification of legislation. Presently, there is a portal (NIR, Norme in rete)9 which operates as a

meta-search engine on a number of national and local government sites. The project is managed by

the National Centre for Informatics in the Public Administration (CNIPA, Centro Nazionale per

l’Informatica nella Pubblica Amministrazione),10 which participates to the European debate about

standardization and integration of legal documentation formats. Partners in the project are several

public bodies and research centers. Recently, the project has been entrusted by law11 to the Ministry

of Semplification.12

Archivists are involved in defining standards and guidelines for public bodies documentation. They

are concerned about the capacity of all of these bodies to ensure effective preservation,

5

Law 9th Jenuary 2004, n. 4, http://www.pubbliaccesso.gov.it/normative/legge_20040109_n4.htm.

http://www.gazzettaufficiale.it.

7

IPZS, Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato, http://www.ipzs.it/home.htm.

8

Law 22nd April 1941, n. 633, consolidated version (2008),

http://www.siae.it/documents/BG_normativa_leggedirittoautore.pdf.

9

http://www.nir.it/.

10

http://www.cnipa.gov.it.

11

Law 18th February 2009, n. 9, http://www.camera.it/parlam/leggi/09009l.htm.

12

http://www.semplificazionenormativa.it/.

6

3

conservation, authenticity and contextualization of their digital archives.13 The problem lies in

providing effective strategies to support the development of cooperative digital repositories,

managed by competent staff.

For their part, librarians emphasize that all documents produced or financed by public bodies should

be publicly accessible, including databases, and with the only exception of those reserved for

privacy reasons.14

The market of legal information

In the past, the Italian commercial legal publishers occupied an almost exclusive segment of the

market and remained fairly refractory to technological innovation.15 This market is still

characterised by high presence of print publications and local media, but the availability of online

contents is growing, though mostly provided on closed platforms, not OpenURL compliant, and

with technological protection measures sometimes so rigid to make it difficult even legitimate

utilizations. Moreover, rarely the licenses include post-cancellation rights or guarantees for longterm access to digital resources. Anyway, the recent trend is clearly towards a quantitative and

qualitative growth of online products and services.

This growth has been fostered by a process of mergers and acquisitions that led to the

concentration of publishing companies. In facts, most of the Italian commercial legal publishing

market is predominantly in the hands of two or three big groups, including the multinational

Wolters Kluwer,16 that can cover the costs of innovation. Under this point of view, the unrestricted

access to an increasing amount of primary and secundary online sources, made available by public

sector, and also by associations and individual professionals, has the merit to rebalance the market,

preventing monopolies and stimulating the development of communication patterns more suitable

to the emerging needs of research and teaching.17 To meet these needs, many librarians and

13

Mariella GUERCIO, Gli archivi come depositi di memorie digitali. “Digitalia: rivista del digitale nei beni culturali”,

v. 3 (2008), n. 2, http://digitalia.sbn.it/upload/documenti/Digitalia20082_globale.pdf?l=it. Maria Grazia PASTURA

Codice dell’amministrazione digitale: problemi e prospettive archivistiche. “Quaderni CNIPA”, n. 25 (Maggio 2006),

http://www.cnipa.gov.it/site/_files/estratto_da_Quaderno_25.pdf.

14

ASSOCIAZIONE ITALIANA BIBLIOTECHE. REDAZIONE DFP, Stato e necessità della documentazione di fonte pubblica in

rete. In L'informazione pubblica dalla produzione alla disponibilità. Giornata di studio in occasione del decennale del

repertorio DFP, Documentazione di Fonte Pubblica in rete (1997-2007), Roma, 23 Novembre 2007,

http://www.aib.it/dfp/c0711d.htm3. See also ASSOCIAZIONE ITALIANA BIBLIOTECHE, Accesso pubblico alla letteratura

scientifica. La posizione dell’AIB. Roma, Associazione Italiana Biblioteche, 18 Novembre 2006,

http://www.aib.it/aib/cen/open.htm.

15

See Sonia CAVIRANI, Società dell’informazione e biblioteche giuridiche: che cosa sta cambiando? “Biblioteche oggi”

v. 21 (2003), n. 4, p. 75-77, http://www.bibliotecheoggi.it/2003/20030407501.pdf.

16

http://www.wki.it/gruppo.asp.

17

See Allen H. RENEAR and Carol L. PALMER, Strategic reading, ontologies, and the future of scientific publishing.

“Sciencce

magazine »,

v.

325

(2009),

n.

5942,

p.

828-832,

http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/325/5942/828.

4

researchers, substained by the Conference of the Rectors of the Italian Universities (CRUI), and by

the Italian Library Association, are strongly committed in advocacy and initiatives for the

development of economically sustainable new publishing models.18

A crucial issue is the lack of effective integration between different types of sources (both fee and

free). In the Google era, publishers, libraries, and all the traditional players in the market of legal

information are faced with a challenge: even if user needs and behaviours are very different,

depending upon their legal competencies, their skills in legal research, and the aims of their

reserchs, however all users - ordinary people as well as experts; past generation users, who are not

familiar with digital environment, as well as new generation users, who attend frequently social

networks and wikis to work in collaboration with their colleagues; professors as well as

undergraduate students - converge on some common expectations: obtaining quick, easy and

transparent access to all relevant sources of information; being able and obtaining facilities to

navigate within the mare magnum (“great sea”) of informations; being able to select reliable

informations and documents; being able to interact with the information systems for

personalization / profiling of the services; being able to reproduce and re-use informations and

documentations for their purposes. Meeting this challenge without leading to a universal monopoly

on information should require cooperation between public and private content and service

providers for the adoption of open standards for interoperability and information discovery.

Another crucial issue is the need of multilingual access to Italian legal sources: presently, they are

available only in Italian language, which is not widespread in Europe and foreign countries. As a

consequence, many foreign people working in Italy may not understand our legal system because

of language barriers. Moreover, the Italian legal culture and tradition is likely to remain unknown

outside Italy. If European integration and building of a global democracy require the comparison

and the constant dialectic between different cultures, the language gaps should be bridged.19

Shared access, cooperation in creating and gathering metadata and vocabularies, multilingualism:

these are exactly the new frontiers of bibliographic control in 21st Century.20

18

For more informations on the Italian activities about Open Access, see Il wiki sull’Open Access in Italia,

http://wiki.openarchives.it/index.php/Pagina_principale, and the web pages of CRUI. Working Group on Open Access,

http://www.crui.it/HomePage.aspx?ref=894.

19

Nicola PALAZZOLO, Lingua del diritto e identità nazionali: tra storia e tecnologia. Paper of the Conference L’italiano

e l’Europa. Punti di vista sull’identità linguistica e culturale, organised by Opera del Vocabolario Italiano in

collabouration with Accademia della Crusca, Florence, 6th June 2005. In Id., Il giurista informatico. Nuovi profili di

un’esperienza scientifico-organizzativa (2002-2008). Catania, CUECM, 2008, p. 49-65. Electronic version:

http://www.ittig.cnr.it/Ricerca/Testi/palazzolo2008f.pdf. Precedently published in Lingua giuridica e tecnologie

dell’informazione, edited by di Nicola Palazzolo. Naples, ESI, 2006, p. 9-27.

20

See On the record: report of the Library of Congress Working Group on the future of the bibliographic control.

Washington DC, Library of Congress, January 9, 2008.

5

Law libraries collections as cultural heritage

Although they are often directly involved in publication and in dissemination of legal information,

as well as in information literacy activities, libraries are not mentioned in the Italian legislation on

eGovernment, nor in the legislation on education and research.

They are mentioned, together with museums and archives, in a specific Code enacted in 2004,

regarding the protection of cultural heritage.21 It provides that all public bodies must ensure

conservation and access to their library collections, and that State and Regions should define the

policies for valorisation and preservation. It is interesting that this Code provided for the first time

in Italy an official definition of the term “library”.22 While the objectives of access, protection and

valorisation of library collections should allow, at least, digitization of printed works, presently, the

Italian copyright law does not provide an exception to allow libraries to digitise copyrighted works,

even for conservation.

3. Law libraries and the national (law) library system

Public bodies are almost completely autonomous on the organization of their libraries.23 The

obligation to ensure access and preservation, as provided by law, is not accompanied by effective

instruments for monitoring and evaluation of activities. State and Regions can encourage good

practices and the coordination of library services through appropriate legislation and actions. In

facts, there are Regions distinguished by the effectiveness of their action in this direction, in other

cases interventions are limited to occasional regional funding.

The national library services are entrusted to the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities.24 A

department of the Ministry, the General Directorate for Library Heritage, Cultural Institutes and

21

Legislative

Decree

22nd

Genuary

2004,

n.

42,

consolidatet

version

(2008),

http://www.beniculturali.it/mibac/export/MiBAC/sito-MiBAC/MenuPrincipale/Normativa/Norme/index.html.

For a

summary of national legislation relating to libraries, see Fausto ROSA, Legislazione statale = State legislation. In

“AIB-WEB. Il mondo delle biblioteche in rete = Library and Information Science”. Rome, Associazione Italiana

Biblioteche, last update: 2007-05-22, http://www.aib.it/aib/lis/lpi08a.htm.

22

"... a permanent structure which collects, catalogues and maintains an organized set of books, materials and

informations, edited or published in any media, and ensures their consultation to promote reading and study.”

(Paragraph 101).

23

The only general regulation on libraries covers the libraries affiliated to the Ministry of Heritage and Cultural

Activities (see the Decree of the President of the Italian Republic 5th July 1995, n. 417,

http://www.bncf.firenze.sbn.it/oldWeb/Privacy/dpr_5_7_95_nr147.pdf. Apart from the two National Central Library of

Rome and Florence, the others are historical libraries, some of which retain the status of "national" or "university"

library in consideration of the role they had in the past.

24

This Ministry was established by Law 29th January 1975, n. 5. Since then, it has been several times reorganized.

Today, its competencies range from archeology to the spectacles. In the past, libraries, archives and museums were

entrusted to the Ministry of Education (today called “ Ministry of Education, University and Research”). In the opinion

of some experts, this separation of competencies did not produce positive results. See Salvatore SETTIS, Il rilancio dei

beni

culturali.

“La

Repubblica”,

28th

April

2006,

p.

25,

http://ricerca.repubblica.it/repubblica/archivio/repubblica/2006/04/28/il-rilancio-dei-beni-culturali.html.

6

Copyright (Direzione Generale per I Beni librari, gli Istituti culturali e il Diritto d’autore),25

coordinates the national libraries and the national bibliographic services.

Another department of the same Ministry, the General Directorate for the Achives (Direzione

Generale per gli Archivi)26 coordinates the archives, and particularly: the Central State Archive and

the State Archives in every Province27, the structures responsible in every region for the supervision

and control over non-state public archives (Soprintendenze regionali archivistiche)28, and the

national agency for archival standards (ICAr, Istituto Centrale per gli Archivi).29

Preservation and restoration of documents of cultural interest, including those privately owned,

should be under the control of the Ministry and/or of the Regions.

The following are some details on the main law libraries and legal documentation services in Italy:

law legal deposit libraries; national bibliographic agency; parliamentary libraries; ministry and court

libraries; regional assembly libraries; university law libraries; local government public libraries;

other relevant documentation services.

Law Legal deposit libraries

The system of legal deposit has been recently reformed.30 The reform includes the online

documents and provides more effective procedures than in the past, eliminating some intermediate

transactions. Under the law, the publisher must deliver two copies of its publications to the two

National Central Libraries of Florence31 and Rome,32 and two other copies to the local deposit

libraries in the region where is its headquarters.33

In the case of legal publications, a fifth copy must be delivered to the Central Library of the

Ministry of Justice.34 In addition, the Central Library of the Ministry of Justice, the Libraries of the

Senate35 and of the Chamber of Deputies, 36 and the Libraries of the Regional Assemblies and of the

25

http://www.librari.beniculturali.it.

http://www.archivi.beniculturali.it/.

27

http://www.archivi.beniculturali.it/UCBAWEB/indice.html.

28

http://www.archivi.beniculturali.it/UCBAWEB/indicesopr.html.

29

http://www.icar.beniculturali.it/index.php?it/1/home. Two databases - covering, respectively, State and non-State

archival documentation - are available through this site: SIAS, Sistema integrato degli archivi nazionali,

http://www.archivi-sias.it/; SIUSA, Sistema Informativo Unificato per le Soprintendenze Archivistiche,

http://siusa.archivi.beniculturali.it/cgi-bin/pagina.pl?RicLin=en

30

Law 15th April 2004, n. 106, http://www.senato.it/parlam/leggi/04106l.htm; Decree of the President of the Italian

Republic 3rd May 2006, n. 252, http://www.librari.beniculturali.it/upload/documenti/Regolamento_deposito_legale.pdf.

31

http://www.bncf.firenze.sbn.it/.

32

http://www.bncrm.librari.beniculturali.it/.

33

Regional deposit libraries are those listed in the Ministerial Decree 28th December 2007,

http://www.librari.beniculturali.it/upload/documenti/Testo%20decreto%20firmato%2028-12-2007.pdf?l=it.

34

http://www.giustizia.it/giustizia/it/mg_7.wp.

35

http://www.senato.it/relazioni/21616/genpagina.htm.

36

http://english.camera.it/serv_cittadini/1660/1662/1661/lista.asp.

26

7

Provinces of Trento and Bolzano can obtain the deposit of a copy of all official publications, and

generally any publicly funded publication.

For the implementation of the deposit of online publications, it is required an ad hoc regulation after

a trial based on voluntary deposit. The National Central Library of Florence is conducting this trial.

The reform has increased by about 30% the number of documents deposited. The two central

national libraries are gradually integrating their activities, to reduce redundancies, to optimize the

workflow, and to share resources for the development of conservation strategies. Also their

relationships with the other deposit libraries, at national and local level, should be based on

cooperation and integration of activities, but currently it is not clear how this result will be

achieved.

National bibliographic agency

The National Central Library of Florence (BNCF) publishes the national bibliography (BNI,

Bibliografia Nazionale Italiana), which is articulated in various sections.37 Among these sections,

there is not one covering legal information.

In this regard, it has been suggested that the functions of national law library should be entrusted to

the Parliamentary Libraries and to the Central Library of the Ministry of Justice.38

The BNCF is also the national agency for semantic indexing. Recently, it has published the Italian

translation of the 22nd edition of the Dewey Decimal Classification, and the the new Italian subject

indexing language.39 As for the indexing of legal works, the BNCF cooperates with a major

research center, the Institute of Theories and Techniques of Legal Information (ITTIG, Istituto di

Teorie e Tecniche dell'Informazione Giuridica),40 and with some university libraries specialized in

social sciences.

Another national institute (ICCU, Istituto Centrale per il Catalogo Unico delle biblioteche italiane

e per le informazioni bibliografiche)41 manages the national union catalogue, called Servizio

Bibliotecario Nazionale (SBN)42, and the national digital library project (BDI, Biblioteca Digitale

Italiana).43

SBN is a project started about 30 years ago with the objective of creating not only the union

catalogue, but a national community of libraries and librarians. This project was the first domestic

37

A list of these products is available at the URL http://www.bncf.firenze.sbn.it/pagina.php?id=188.

Il Polo bibliotecario parlamentare. Intervista a Mauro Guerrini. “Minerva Web”, n. 16 (April 2008),

http://www.senato.it/relazioni/21616/48230/152017/152024/152025/genpagina.htm.

39

BIBLIOTECA NAZIONALE CENTRALE DI FIRENZE, Nuovo soggettario : guida al sistema italiano di indicizzazione per

soggetto : prototipo del Thesaurus. Milano, Editrice bibliografica, 2006.

40

http://www.ittig.cnr.it/.

41

http://www.iccu.sbn.it/genera.jsp.

42

http://www.sbn.it/opacsbn/opac/iccu/informazioni.jsp.

43

http://www.iccu.sbn.it/genera.jsp?s=18.

38

8

case of online public service based on cooperation between State, Regions and Universities.

Unfortunately, it was too much advanced at the time it was projected, and already obsolete when it

was implemented.44 So, many libraries chose not to partecipate and preferred other library systems.

Presently, the SBN participating libraries are 4,00045 out of a total of about 15,000 existing

libraries.46 It currently contains about 11 million bibliographic records that represent almost 47

million holdings.47 In recent years, the architecture of SBN has been restructured to enable the

integration of local catalogs managed by different softwares.

BDI is a project aimed to the interoperability of the Italian digitised collections in Italy, for their

integration into a national portal (called Internet culturale)48 and in the European Digital Library.

Parliamentary libraries

The most important law libraries in Italy are those of the two branches of the Italian Parliament:

Senate Library (Biblioteca del Senato della Repubblica)49 and Chamber of Deputies Library

(Biblioteca della Camera dei deputati).50 Founded in 1848, they support the parlamentary work by

providing documentation and reference services. They are open to the public and are committed in

many activities for the dissemination of legal information and legal information literacy. In 2007

they have unified their collections, their catalogs51 and their services (this coordination is called

Polo bibliotecario parlamentare).52 They hold almost 2 million works, more than 2.000 journals

and about 100 bibliographic and full-text databases. Of these, some unique collections of grey

literature. One of their most relevant projects is the digitization, made by the Chamber of Deputies

Library, of the entire collection of the Italian Republic Parliamentary acts, from 1948 to 1996

(when the digital publication of laws and other Parliamentary acts has become current practice).53

Moreover, the Chamber of Deputies Library is involved in various publishing projects54, like the

44

See Tommaso GIORDANO, Riconfigurare SBN. “Biblioteche oggi”, v. 26 (2008), n. 8, p. 7-12. Electronic version at

the URL http://www.bibliotecheoggi.it/content/20080800701.pdf

45

ISTITUTO CENTRALE PER IL CATALOGO UNICO DELLE BIBLIOTECHE ITALIANE E PER LE INFORMAZIONI

BIBLIOGRAFICHE, I Poli e le Biblioteche SBN. Rome, ICCU, http://www.iccu.sbn.it/moduli/poli/poli.jsp?s=5.

46

ISTITUTO CENTRALE PER IL CATALOGO UNICO DELLE BIBLIOTECHE ITALIANE E PER LE INFORMAZIONI BIBLIOGRAFICHE,

Anagrafe delle biblioteche italiane, http://anagrafe.iccu.sbn.it/index.html.

47

ISTITUTO CENTRALE PER IL CATALOGO UNICO DELLE BIBLIOTECHE ITALIANE E PER LE INFORMAZIONI

BIBLIOGRAFICHE, Le basi di dati. Rome, ICCU, last update: 22 June 2009, http://www.iccu.sbn.it/genera.jsp?id=339.

48

Internet culturale, http://www.internetculturale.it/.

49

http://www.senato.it/english/relations/28062/genpagina.htm.

50

http://english.camera.it/serv_cittadini/1660/1662/1661/lista.asp.

51

http://opac.parlamento.it/F.

52

http://www.parlamento.it/polobibliotecario/44519/gencopertina.htm.

53

http://legislature.camera.it/.

54

http://www.camera.it/serv_cittadini/23006/23054/documentotesto.asp.

9

Annual report on legislation in Italy and in Europe (Rapporto sulla legislazione tra Stato, Regioni e

Unione Europea).55

Ministry and Court Libraries

Many ministerial libraries were born in the nineteenth century, to support the Ministry officials

work, so their historical collections reflect the evolution of the Italian public administration. From

the second half of the nineteenth century, they entered in a phase of neglect and abandonment.56 In

the twenty-first century, in a system of legal relations increasingly complex, they began to regain

visibility and importance as advanced documentation centers.

Most of them participate in the national catalog SBN. Each Ministry web site57 often include

informations on its libraries, but there is not yet a general Ministry libraries network.

The most important Ministry library is the Central Library of the Ministry of Justice (Biblioteca

centrale giuridica del Ministero della Giustizia),58 which has been entitled to a copy of all works

published in Italy since 1880. Together with the Parliamentary Libraries it could be at the heart of

the national coordination of law libraries. It is not open to the general public, but teachers and

students in law are admitted. It joins the SBN national union catalog through a collective catalog59

which includes the Central Library of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and various Court Libraries.

A particular type of governmental libraries are those of the School of Public Administration (SSPA,

Scuola Superiore della Pubblica Amministrazione).60 The SSAP is a school for advanced training of

executives and public officials, under de supervision of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers

(Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri).61 As part of its elearning program, the SSAP has produced

a useful directory of libraries in public administration.62 Its libraries are targeted to teachers and

students of the School itself, but are also accessible to students who pursue degree thesis on topics

related to public administration. Their collective catalog63 is integrated into the national union

catalog SBN.

Regional Assembly Libraries

55

http://www.camera.it/docesta/9383/9387/22159/documentotesto.asp.

Guido MELIS, Passato, presente e futuro delle biblioteche delle pubbliche amministrazioni. In Le biblioteche

dell’amministrazione dello Stato: esperienze a confronto. Proceedings of the Seminar of the Working Group on

Governement Libraries held within the 51. Congress of the Italian Library Association. AIB. Rome, 29 October 2004,

http://www.aib.it/aib/congr/c51/melisint.htm.

57

http://www.governo.it/Governo/Ministeri/index.html.

58

http://www.giustizia.it/giustizia/it/mg_7.wp.

59

http://opac.giustizia.it/SebinaOpac/Opac.

60

http://www.sspa.it/.

61

http://www.governo.it/presidente/index.html.

62

http://formazione.formez.it/biblioteche_per_la_pa.html.

63

http://sspa.sebina.it/SebinaOpac/Opac.

56

10

Regions, provided by the Italian Constitution of 1948, were actually introduced in 1970.64 The role

of local public bodies (Regions, municipalities, metropolitan cities, provinces) is becoming

increasingly important, especially after a 2001 reform.65 The Regions and the Provinces of Trento

and Bolzano have legislative power over all the matters that the Constitution does not expressly

reserve to the central State. Moreover, according to the principle of subsidiarity, the administration

is entrusted to entities closest to recipients. Even on the matters entrusted to the State, Regions and

the other local authorities participate in the decision-making on all issues which may have impact

on their territories.

Consequently, the Regional Assembly libraries should grow as legal documentation services

addressed not only to the Assembly members, but also to the other local authorities and to the local

government public libraries and information centers. Moreover, they should be the local loops of a

national law libraries network. Most of them participate in the national union catalog SBN and in a

specific Regional Assembly Libraries meta-search engine.66 In some cases they cooperate with law

faculties for collection development and training activities.67

University law libraries

The italian universities with a Law faculty are 63.68 Some of them were founded in the Middle

Ages, and this very ancient history is reflected in their collections. They are highly active in hybrid

and digital collection development, as well as in the development of advanced reference guides and

tools for research and e-learning.69 Many are involved in the management of institutional publishing

projects and / or of the institutional open archives. As regards the information literacy, active

involvement of libraries in the university courses is gradually becoming a rule, especially in the

Center-North of the country, but it is not yet an established practice. Students often learn the

methodologies of research only when preparing the thesis degree, and that's when they discover the

usefulness of the library reference services.

The Italian universities, coordinated (and largerly funded) by the Ministry of Education, University

and Research (Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca),70 are very autonomous

64

Law 16th May 1970, n. 281, http://www.italgiure.giustizia.it/nir/lexs/1970/lexs_225225.html.

Constitutional

Law,

18th

October

2001,

n.

3.

English

version:

http://www.senato.it/documenti/repository/istituzione/costituzione_inglese.pdf.

66

MetaOPAC delle Biblioteche delle Assemblee regionali, http://www.parlamentiregionali.it/biblioteche/metaopac.php.

67

An example is the partnership between Emilia-Romagna Regional Assembly Library and the University of Bologna

law

libraries.

See

the

announcement

at

the

URL

http://assemblealegislativa.regione.emiliaromagna.it/wcm/biblioteca/acp/coll/progetti/index/biblio/giuridiche/biblioteche.htm.

68

See the database of the MINISTRY OF EDUCATION, UNIVERSITY AND RESEARCH, CercaUniversità,

http://cercauniversita.cineca.it/.

69

For an example, see the reference guide of the UNIVERSITY “CARLO CATTANEO” OF CASTELLANZA (MILAN).

BIBLIOTECA “MARIO ROSTONI”, L’informazione giuridica, http://www.biblio.liuc.it/vlibrary/VLIndici.asp?codice=15.

70

http://www.miur.it.

65

11

bodies,71 so the organization of their libraries depends on the choices of each university: some have

many department libraries, others are grouped in larger thematic areas to facilitate coordination.

Generally, the definition of their policies and scientific profile are entrusted to boards compounded

by professors and librarians, while the management is entrusted to librarians. The continuous cuts to

funds for research and increasingly unsustainable pricing policies of the publishers have brought

university libraries, first, to overcome the internal fragmentation, then to cooperate with external

university library systems. Most of them participate in consortia and to a national co-ordination of

negotiations under the auspices of the Conference of the Rectors of the Italian University (CRUI,

Conferenza dei Rettori delle Università Italiane)72. Not all of them join the national catalog SBN,

anyway the majority are involved in general and specialized networks, created and managed by

some universities and research institutions: the national catalog of journals held by Italian libraries

(ACNP),73 the analytic indexing of Italian journals of law, economy and social science holded by

Italian libraries (ESSPER),74 the Network of InterLibrary Document Exchange (NILDE)75, and so

on.

Local Government Public Libraries

In Italy there are excellent public libraries, but also in this case the situation is uneven: in the South

of the country, many library systems are poorly developed. We all know that public libraries are key

tools to promote cultural progress and active citizenship. In the case of legal information, their role

could become increasingly important despite the increasing of online information: given that most

social relationships are regulated by rules of law, knowledge and understanding of norms is

essential for all. Moreover, in a pluralistic legal system like the Italian (i.e., copresence of the

International Law, the European Community Law, the Local Autonomies Law, and so on), the

occurrence of antinomies adds complexity to the choice of the rule to be applied to each case. Of

cours, this should require expert legal consulting services, but why don’t suggest a cooperation in

71

See Paragraph 33 of the Italian Constitution,

http://www.senato.it/documenti/repository/istituzione/costituzione_inglese.pdf, and Paragraph 6 of the Law 9th May

1989, n. 168, http://www.miur.it/leggi/l168arti.htm.

72

http://www.crui.it.

73

http://acnp.cib.unibo.it/cgi-ser/start/it/cnr/fp.html. Initially created and maintained by the National Council of

Researchs (CNR, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche), at the present the catalogue is hosted and maintained by the

University of Bologna.

74

http://www.biblio.liuc.it/essper/spoglio.htm. Created, hosted and maintained by the Library of the University “Carlo

Cattaneo” of Castellanza (Milan).

75

http://nilde.bo.cnr.it/. Created and maintained by the “Area Library”, the library of the Institutes of Bologna of the

National Council of Research (CNR, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche).

12

this matter between local government libraries, other public offices, law faculties and professional

orders?76

Other relevant documentation services

A very important tool is the Italian government information on the net (DFP, Documentazione di

Fonte Pubblica in rete),77 a guide and a data-base of Internet resources, hosted on the Italian

Library Association web site and entirely realised on a voluntary bases.

A special mention merits the Institute of Theory and Techniques of the Legal information (ITTIG,

Istituto di Teoria e Tecniche dell’Informazione Giuridica)78, which is part of the Italian National

Council for Researchs (CNR, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche).79 ITTIG is specialised in

“Informatics and Law” and is involved in various national and international projects. One of its

publications is the DoGi Database – Legal Literature : Abstract of articles published in italian law

periodicals.80 Differently from the ESSPER project mentioned above, DoGi is a bibliography and

not an analytic catalogue.

Finally, some notes on the most relevant public source of legal information: Italgiure Web,81 the

databases of legislation, case laws and legal literature published by the Electronic Documentation

Center (CED, Centro Elettronico di Documentazione) of the Italian Supreme Court (Corte di

Cassazione).82 In the past, all these databases were fee. From 2004,83 othe databases of legislation

and of the Constitutional Court decisions are free, through the cited NIR - Norme In Rete metasearch engine.

4. Law Librarians: education and profession

The development of electronic resources and the complexity of their management have fostered the

recognition of the importance of librarians professional work, and the growth of their prestige

within the parent institutions. For now this is still a trend, not an achieved goal. In facts, it does not

exist in Italy a standardized curriculum for the career of law librarians, as well as for librarians in

76

Such a cooperation is underway between the public Library “Villa Amoretti” of Turin and the local Notary Board.

See Il notaio è un libro aperto (transl.: “The notary is an open book”),

http://www.torinocultura.it/portal/page?_pageid=67,1667702&_dad=portal&_schema=PORTAL&mostraCalendario=1

&idEvento=44463&idCanale=1.0.

77

http://www.aib.it/dfp/dfp.htm3.

78

http://www.ittig.cnr.it/.

79

http://www.cnr.it.

80

http://nir.ittig.cnr.it/dogiswish/consistenze/dogi-rivEng.htm.

81

http://www.italgiure.giustizia.it/.

82

http://www.cortedicassazione.it/.

83

Decree of the President of the Italian Republic 17th June 2004, n. 195,

http://www.italgiure.giustizia.it/nir/lexs/2004/lexs_403491.html.

13

general, thought the need for qualified personnel is now felt by many institutions, which are

adopting criteria for recritment much more rigorous than in the past.

In the previous paragraph, we have already seen that the information literacy of students in Law is

subject to specific programs only in some universities. In some degree and post-degree courses,

there is also a teaching in Legal informatics (Informatica giuridica), part of which focuses on legal

research methodologies. All of these programs are not specifically aimed to train law librarians. So,

a graduate in Law should become expert in Library Science after attending a master or a second

level degree in Library science.84 The problem is that, given that the profession of librarian in Italy

is not attractive from an economic standpoint, there are few legal experts interested in this career.

Moreover, University courses in Library science are included in the faculties of Arts and

Humanities, or of Cultural Heritage ("Beni culturali"), and this influences curricular contents and

teaching approachs of these courses: they are perfect to give broad and theoretical knowledge of

books and documents as the witness of a cultural tradition, but often deficient in providing

competencies in management, law, communication, technology, which are necessary for today

library work.

So, in most cases, librarians acquire legal competencies on the job and / or in seminars and courses

organized by the parent institution, or external agencies. The need for specialization and constant

updating is expressed primarily by librarians themselves, stimulated by the reflections and debates

within the international professional community, and also by the competition in the labor market

that, with the shrinking of employment opportunities, has become very hard.

5. Conclusions.

The role of law libraries in the Italian legal information system appears increasingly crucial, despite

they have been considered by the Italian legislator little more than repositories of books and other

materials. The lack of a general national law libraries network or coordination makes their

contribution less visible and effective than it should be. Library cooperation in Italy has become an

established practice, but at the moment the absence of a coherent strategy for libraries at political

level is still slowing a full integration.

84

Presently, in Italy there are three levels of academic education: “Laurea”, “Laurea magistrale”, “Dottorato”. PostDegree Masters organised by Universities and/or other institutions are considered professional qualifications, but not

academic qualifications. The Degree in “Archival and Library Scence” (“Archivistica e Biblioteconomia”) is a second

level

degree.

See

the

Ministerial

Decree

22nd

October

2004,

n.

470,

http://www.miur.it/0006Menu_C/0012Docume/0098Normat/4640Modifi_cf2.htm, and the Ministerial Decree

16th March 2007, http://www.miur.it/Miur/UserFiles/Notizie/2007/DMCdL_magistrale.pdf.

14

In next future, due to the digital convercence, all of “traditional” activities of law libraries

(collection development, preservation, bibliographic control, reference services, quality of

information ensuring) will be even more needed and complex. In the meantime, they are developing

new services and activities, such as institutional publishing and support to programs for information

literacy. As a consequence, their prestige in society and in their parent institutions tends to grow,

although, paradoxically, their budgets have never been so insufficient as some years now.

Information technologies permit to strengthen interdisciplinary and interinstitutional cooperation,

integrate workflows and new kinds of documents, meet the expectations of different users, realize

information architectures strongly oriented to interactivity and user participation. EGovernment

projects as well as digital library projects are expected to converge on these aims, thanks to the

contribution of several public and private players. Among all of these players, libraries are the most

committed to defending user access right, because this is properly their mission. For this reason,

libraries should be at the hearth of those projects.

15

Scaricare