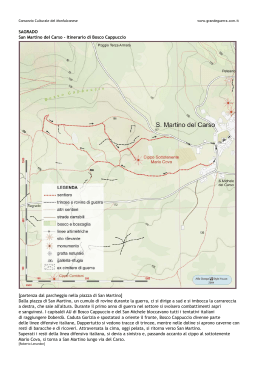

CDS 503/1-2 D D D DIGITAL LIVE RECORDING LUIGI CHERUBINI (Firenze, 1760 - Parigi, 1842) LO SPOSO DI TRE E MARITO DI NESSUNA (THRICE BETROTHED, NEVER WED) Dramma giocoso in due atti Libretto di Filippo Livigni - Edizione Boosey & Hawkes, Berlino Una produzione del Festival della Valle d’Itria di Martina Franca Direttore artistico: Sergio Segalini Donna Lisetta (soprano) Don Martino (tenore) Don Pistacchio (baritono) Donna Rosa (soprano) Don Simone (baritono) Bettina (soprano) Folletto (baritono) Maria Laura Martorana Emanuele D’Aguanno Giulio Mastrototaro Rosa Anna Peraino Vito Priante Rosa Sorice Gabriele Ribis ORCHESTRA INTERNAZIONALE D’ITALIA Direttore: Dimitri Jurowski Regia: Davide Livermore CD 1 1 76:52 - Sinfonia 4:48 ATTO PRIMO 2 - Guardate quanti giochi (Don Simone) 3 - Facciamo più guadagno (Bettina) 4 - Bella cosa ch’è il viaggiare (Lisetta, Martino) 5 - Sorella mia, giudizio (Martino) 6 - Or che son vestito in gala (Don Pistacchio) 7 - Orsù, villani (Don Pistacchio) 8 - Superbo di me stesso (Martino) 9 - É questa la locanda (Donna Rosa) 10 - Gioia bella (Don Simone) 11 - Lisetta allegramente (Lisetta) 12 - Chi crede a voi altri uomini (Donna Rosa) 13 - Quella signora è matta (Don Pistacchio) 14 - Moglie quella! Ma di chi? (Don Pistacchio) 15 - Chi tiene moneta (Folletto) 16 - Sono amante e son pietosa (Lisetta) 17 - Ecco la falsa sposa (Don Pistacchio) 18 - Donne belle, son fallito (Don Pistacchio) 19 - Mio caro Don Simon (Donna Rosa) 20 - Se la bella del ritratto (Martino) 21 - Zeffiretti che placidi e cheti (Lisetta) 2 5:50 3:49 2:03 1:45 2:48 3:27 5:19 1:41 2:17 3:19 4:51 3:16 6:00 2:13 5:46 2:04 4:22 0:57 5:01 5:06 CD 2 1 74:03 - Bada bene ser nipote (Don Simone) 5:43 ATTO SECONDO 2 - Che ne dici Bettina (Folletto) 3 - Un uomo astuto e destro (Folletto) 4 - Certo, chi è destro al mondo (Bettina) 5 - No, tanto scortese (Bettina) 6 - Signor zio, signor zio (Don Pistacchio) 7 - Qui è Baldo, e Bartolo (Martino) 8 - Signoris benvenutis (Don Pistacchio) 9 - Facciamo un po’ silenzio (Don Pistacchio) 10 - Adesso che mi sono consigliato (Don Simone) 11 - Vezzosa cara sposa (Don Simone) 12 - Così, così si faccia (Donna Rosa) 13 - Or che dorme il mio sposino (Donna Rosa) 14 - Eccoli, sono qua (Martino) 15 - Ah no, non pianger più (Lisetta) 16 - Dolce fiamma del mio core (Lisetta) 17 - Lisetta m’ha capito (Martino) 18 - Askara ki kila (a 4) 19 - La scena veramente è stata bella (Folletto) 20 - Quando il labbro io movo a riso (Martino) 21 - Sento un’amena voce (Donna Rosa) 22 - Tutto questo è accaduto? (Bettina) 23 - Prigioniera abbandonata (Lisetta) 24 - Allegri staffieri (Bettina) 25 - Cara sposa, vezzosa, bellina (Don Simone) 3 1:47 2:52 1:57 4:01 0:38 1:36 1:10 3:07 1:02 1:50 2:13 4:20 1:32 3:03 5:00 0:38 6:27 1:16 3:24 4:19 2:41 4:06 3:51 5:18 uando nel 1994, su insistenza di Rodolfo Celletti, presi in mano la direzione artistica del Festival di Martina Franca, i titoli previsti erano già stati pensati dal mio illustre predecessore. Decisi soltanto di riproporre la sua Sonnambula nelle tonalità originali. Il secondo titolo Amor vuol sofferenza di Leo era un dovuto omaggio alla straordinaria cultura pugliese del ’700. Nel 1995, riprendendo il filone già annunciato nel 1984 con Il Giuramento e nel 1990 con Il Bravo, titoli però già conosciuti dai melomani, tentai una prima ripresa in tempi moderni di un Mercadante che ebbe grande fama nella prima metà dell’800: Caritea Regina di Spagna. Il compositore di Altamura rivelava in questa partitura giovanile una profonda conoscenza dell’universo rossiniano. Accanto alla pugliese Caritea la Médée di Cherubini sembrava quasi un déjà-vu, o meglio déjà-entendu. Dopo l’irragiungibile Medea di Maria Callas nell’assurda traduzione italiana con recitativi orchestrati, altre dive della lirica avevano tentato di eguagliare il famoso soprano greco ripristinando l’originale francese, ma senza basarsi su una coerente edizione critica e soprattutto senza restituire i dialoghi parlati, Shirley Verrett per prima! Le serate nel cortile del Palazzo Ducale permisero in tal modo di scoprire la vera natura della Médée di Cherubini, ultima grande tragédie lyrique della scuola francese. Ci sono voluti altri dieci anni per poter proporre un nuovo Cherubini al pubblico internazionale, il fortunatissimo Lo sposo di tre e marito di nessuna, scritto per il Teatro San Samuele di Venezia, dove fu rappresentato per la prima volta nell’autunno del 1783. Dopo il dramma sanguinario di Médée, la pochade alla Feydeau di Filippo Livigni sorprende anche se il chassé-croisé caro al marivaudage settecentesco e tanto utilizzato da Da Ponte nelle opere di Mozart è presente fin nelle farse del giovane Rossini all’inizio dell’ottocento. Ma la sottile ironia di Cherubini tradot- ta da un’architettura orchestrale molto più vicina a Mozart che a Cimarosa, basti ascoltare il gran finale, preannuncia le théâtre de boulevard di Feydeau e Labiche. Disgraziatamente l’ascoltatore, disturbato dai rumori dei continui movimenti scenici, giudicherà l’opera e i suoi esecutori solo con l’orecchio. Gli spettatori del luglio 2005 hanno invece potuto godere questo piccolo gioiello musicale allettando l’occhio grazie alla regia di Livermore che, cosciente della modernità del soggetto, scavalcava Labiche e si spingeva alle prime esperienze del cinema muto. Come ha spesso dimostrato Riccardo Muti, senz’altro il più importante promotore della Cherubini Renaissance del post Callas, l’illustre Luigi, considerato da molti come un accademico, ha tutte le carte in regola per rivivere nel XXI secolo. Come nel novembre del 1783, i sette protagonisti di Martina Franca sono giovani, giovanissimi cantanti e, come all’epoca, cantanti attori o attori cantanti, il limite tra teatro e opera nel ’700 non essendo mai stato chiaro per quanto riguarda l’opera buffa. Q Sergio Segalini Direttore Artistico del Festival di Martina Franca 4 hen, in 1994, I was asked by Rodolfo Celletti to become the artistic director of the Martina Franca Festival, that year’s programme had already been decided by my illustrious predecessor. I only chose to propose Sonnambula in the original tonalities. The second title, Amor vuol sofferenza by Leo, was a rightful homage to the extraordinary Pugliese culture of the 1700s. In 1995, pursuing the course begun in 1984 with Il Giuramento and continued in 1990 with Il Bravo (titles that are wellknown to opera lovers), I proposed the first performance in modern times of an opera by Mercadante, a composer who attained great fame in the first half of the 1800s: Caritea Regina di Spagna. That early score by the composer from Altamura revealed a profound knowledge of the Rossini universe. Beside Caritea, Cherubini’s Médée almost seemed a déja-vu, or – to be more precise – a déja-entendu. After the extraordinary Medea of Maria Callas in the absurd Italian translation with orchestrated recitatives, other divas – among them Shirley Verret – had tried to equal the famous Greek soprano performing the original French version, although without using a critical edition and especially the original spoken dialogues. And so it was in the courtyard of Palazzo Ducale that the true nature of Cherubini’s Médée, the last great tragédie lirique of the French school, was rediscovered. Ten years later, here is another opera by Cherubini, the delightful Sposo di tre e marito di nessuna written for Venice’s Teatro San Samuele, where it was first staged in the autumn of 1783. After the bloody tragedy of Médée, Filippo Livigni’s pochade à-la-Feydeau surprises, even though the chassé-croisé dear to 18th-century Marivaudage and so extensively used by Da Ponte in Mozart’s operas is present up to the farces of the young Rossini at the beginning of the 1800s. But Cherubini’s subtle irony, translated into an orchestral architecture that is much closer to Mozart than Cimarosa – as the finale shows – heralds Feydeau’s and Labiche’s théâtre de boulevard. Unfortunately the listener will judge this work and its performers only through their ears, and stage noises are quite distracting. The audience of the July 2005 performance, instead, enjoyed this music gem also through the direction of Livermore who, recognising the subject’s modernity, went beyond Labiche and ventured into silent cinema. As it has often been proven by Riccardo Muti, by far the most important promoter of the post-Callas Cherubini renaissance, the illustrious Luigi, considered by many a scholastic composer, has qualities worthy to be revived in the 21st century. As in November of 1783, also in Martina Franca the seven protagonists are young, very young singers and, as for the première, they are singer-actors, or actor-singers, the boundary between theatre and opera in the 1700s having never been all that clear as far as opera buffa is concerned. W Sergio Segalini Artistic Director of the Martina Franca Festival 5 ls ich 1994 auf Drängen von Rodolfo Celletti die künstlerische Leitung des Festivals in Martina Franca übernahm, waren die aufzuführenden Werke bereits von meinem ausgezeichneten Vorgänger bestimmt worden. Ich entschied nur, seine Sonnambula in den Originaltonarten zu geben. Die zweite Oper – Leos Amor vuol sofferenza – war eine der außerordentlichen Kultur im Apulien des 18. Jahrhunderts geschuldete Hommage. Indem ich 1995 die bereits 1984 mit Il Giuramento und 1990 mit Il Bravo (Werke, welche die Opernfans aber bereits kannten) begonnene Linie fortsetzte, versuchte ich eine erste Wiederaufnahme in moderner Zeit einer Oper von Mercadante, die in der ersten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts sehr bekannt war: Caritea, Regina di Spagna. Der Komponist aus Altamura erwies sich in dieser Partitur aus seiner Jugend als tiefer Kenner von Rossinis Universum. Neben dieser apulischen Caritea schien Cherubinis Medea geradezu ein déjà-vu oder besser déjà-entendu. Nach der unerreichbaren Medea von Maria Callas in der absurden italienischen Übersetzung mit gesungenen Rezitativen hatten andere Operndiven - mit Shirley Verrett an der Spitze - versucht, es dem berühmten griechischen Sopran gleichzutun und nahmen das französische Original wieder auf, ohne aber von einer konsequenten kritischen Ausgabe auszugehen und vor allem, ohne die gesprochenen Dialoge einzusetzen. So ermöglichten es die Abende im Hof des Palazzo Ducale, die wahre Natur von Cherubinis Médée zu entdecken, der letzten großen tragédie lyrique der französischen Schule. Es brauchte weitere zehn Jahre, bis dem internationalen Publikum ein neuer Cherubini angeboten werden konnte, den für das Teatro San Samuele in Venedig geschriebenen und dort im Herbst 1783 uraufgeführten, so erfolgreichen Lo sposo di tre e marito di nessuna. Nach dem blutigen Drama der Médée überrascht die pochade à la Feydeau von Filippo Livigni, auch wenn das der Marivaudage des 18. Jahrhunderts liebe und von Da Ponte in Mozarts Opern so sehr verwendete chassé-croisé in den farse des jungen Rossini zu Beginn des 19. Jahrhunderts vertreten ist. Doch Cherubinis subtile Ironie, die in einer Orchesterarchitektur umgesetzt wird, die Mozart viel näher steht als Cimarosa (man höre nur das große Finale), kündigt das Boulevardtheater eines Feydeau und Labiche an. Leider wird der auch von den Geräuschen der ständig auf der Bühne herrschenden Bewegung gestörte Hörer das Werk und seine Interpreten nur mit dem Ohr beurteilen. Die Zuschauer vom Juli 2005 konnten hingegen dieses kleine musikalische Juwel genießen und durch die Regie Livermores das Auge erfreuen, hatte dieser doch im Bewußtsein der Modernität des Sujets Labiche übersprungen und die ersten Erfahrungen des Stummfilms zum Einsatz gebracht. Wie Riccardo Muti - sicherlich der wichtigste Betreiber der Cherubini-Renaissance nach dem Ereignis Callas - oft bewiesen hat, ist der von vielen als akademisch eingestufte gute Luigi durchaus fähig, im 21. Jahrhundert wieder aufzuleben. Wie im November 1783 sind die sieben Protagonisten in Martina Franca junge, sehr junge Sänger und – wie seinerzeit – schauspielende Sänger oder singende Schauspieler, da im 18. Jahrhundert die Grenze zwischen Schauspiel und Oper hinsichtlich des Buffogenres nie eine deutliche war. A Sergio Segalini Künstlerischer Leiter des Festivals von Martina Franca 6 uand, pressé par Rodolfo Celletti, j’ai accepté en 1994 de prendre la direction artistique du Festival de Martina Franca, les titres prévus avaient été déjà pensés par mon illustre prédécesseur. Ma seule décision a été de reproposer sa Sonnambula dans les tonalités d’origine. Le second titre, Amor vuol sofferenza de Leo, était un hommage à l’extraordinaire culture qui s’était développé dans les Pouilles au dix-huitième siècle. En 1995, reprenant le filon annoncé en 1984 avec Il Giuramento et en 1990 avec Il Bravo – titres déjà connus des mélomanes – j’ai tenté une première reprise moderne d’un Mercadante très célèbre dans la première moitié du dix-neuvième siècle : Caritea Regina di Spagna. Le compositeur originaire d’Altamura, dans les Pouilles, dévoilait dans cette partition de jeunesse une profonde connaissance de l’univers rossinien. Comparée à la Caritea, la Médée de Cherubini avait un je-ne-sais-quoi de déjà vu, ou plutôt de déjà entendu. Après l’incomparable Medea de Maria Callas dans une absurde traduction italienne avec récitatifs orchestraux, d’autres divas de l’opéra – Shirley Verrett en tête – avaient tenté d’égaler la célèbre soprano grecque en reprenant le livret original français, mais sans se baser sur une édition critique cohérente et surtout sans restituer les dialogue parlés. Les soirées dans la cour du Palais Ducal ont donc permis de découvrir la véritable nature de la Médée de Cherubini, dernière grande tragédie lyrique de l’école française. Dix années se sont encore écoulées avant qu’un nouveau Cherubini soit proposé au public international, le très fortuné Lo sposo di tre e marito di nessuna, écrit pour le théâtre San Samuele de Venise où il fut représenté pour la première fois à l’automne 1783. Après le drame sanguinaire de Médée, la pochade à la Feydeau de Filippo Livigni surprend, même si le chassé-croisé cher au marivaudage du dix-huitième siècle et si souvent utilisé par Da Ponte dans les opéras de Mozart est présent dans les comédies burlesques du jeune Rossini dans les premières années du dix-neuvième siècle. Mais l’ironie subtile de Cherubini traduite par une architecture orchestrale bien plus proche de Mozart que de Cimarosa – il suffit pour s’en convaincre d’écouter le grand finale – annonce le théâtre de boulevard de Feydeau et Labiche. Malheureusement l’auditeur, gêné par le bruit des multiples mouvements de scène, ne jugera l’œuvre et ses interprètes que d’une oreille distraite. En revanche, les spectateurs présents en juillet 2005 ont pu savourer cette petite perle musicale, l’œil ravi par la mise en scène d’un Livermore qui, conscient de la modernité du sujet, dépassait Labiche pour parvenir aux premières expériences du cinéma muet. Comme l’a souvent prouvé Riccardo Muti, sans aucun doute le plus important promoteur de la Renaissance de Cherubini après la période Callas, il ne manque rien à l’illustre Luigi, souvent considéré comme académique, pour revivre au XXI siècle. Comme en novembre 1783, les sept protagonistes de Martina Franca sont de jeunes, de très jeunes chanteurs et, comme à l’époque, ce sont des chanteursacteurs ou des acteurs-chanteurs, la frontière entre le théâtre et l’opéra au dix-huitième siècle n’ayant jamais été précisément tracée en ce qui concerne l’opera buffa. Q Sergio Segalini Directeur artistique du Festival de Martina Franca 7 rima di intraprendere l’avventura francese, che lo avrebbe portato a consacrarsi interamente al repertorio serio e soprattutto a dar vita a forme di spettacolo innovative e paradigmatiche per il mondo operistico europeo, Luigi Cherubini (17601842) visse un lungo e attivo periodo italiano durante il quale si impegnò nella composizione dei generi allora in voga, dimostrando di applicare, seppure in modo originale e piuttosto autonomo, gli stilemi e i tratti compositivi tradizionali, apprezzati dal pubblico e ben assimilati dai cantanti. Durante tale attività titoli seri e comici si alternavano con una precisa scansione secondo i dettami del maestro Giuseppe Sarti. Tra il 1780 e il 1784, anno della partenza per l’Inghilterra, Cherubini allestisce infatti ben otto opere (sette serie e una buffa) e tra queste Lo sposo di tre, marito di nessuna, data in Venezia nel teatro San Samuele, nell’autunno 1783. L’esito, secondo quanto riferisce lo stesso autore, appare molto positivo e non soltanto per la divertente trama predisposta da Filippo Livigni, ma soprattutto per certi effetti inediti della parte musicale. Già in apertura, la sinfonia scatenò l’interesse degli ascoltatori per la sua brillantezza arricchita di ritmi lombardi, per la densità del trattamento orchestrale e per la felicità dell’invenzione melodica tutta impostata su due motivi principali ben definiti, il secondo dei quali ampiamente sviluppato e variato. Lo stesso Cherubini si compiacque di questa pagina tanto da riutilizzarla, preceduta da un tempo Adagio, in un’altra opera L’hôtellerie portugaise del 1798, secondo una prassi non comune nel suo catalogo. La vicenda de Lo sposo si dipana sulla base dei mezzi più ricorrenti nel teatro musicale del Settecento, fondendo elementi tipici dell’opera buffa napoletana con passaggi della commedia dell’arte: inganni, travestimenti, equivoci, scene spettrali, processi, duelli, tutti pensati per dar vita a situazioni di esilarante comicità. Desunta da La bottega del caffé (1736) di Carlo Goldoni, la storia di Don Pistacchio, barone di Lagosecco, aspirante sposo della baronessa Donna Rosa, ma alla fine della storia marito di nessuna donna, vede agire sulla scena i tipici ruoli dell’opera buffa italiana, provenienti da differenti classi sociali, dal carattere adeguatamente rimarcato: Donna Lisetta, baronessa e sorella del capitano Don Martino, pure interessato a trovar moglie; Don Simone, zio di Don Pistacchio; Bettina cantatrice di piazza e Folletto, giocatore di bussolotti. Situazioni e personaggi si succedono vorticosamente non trascurando riflessioni sull’amore e massime di natura universale, né evitando caricature e satire velate. Se Don Pistacchio è concepito come caricatura del danaroso, tronfio, ma poco avveduto uomo di campagna, Don Simone e Don Martino sono due caratteri desunti dalla commedia dell’arte: il primo, come Pantalone, e il secondo, tipico cavaliere. Anche la coppia di attori Folletto e Bettina, che intervengono soprattutto per creare confusione all’interno della storia, sono derivati dallo stesso ambiente artistico. Donna Lisetta e Donna Rosa sono invece personaggi seri e sentimentali con venature buffe che concorrono a rimarcare il senso ultimo della storia: la satira delle convenzioni matrimoniali della piccola nobiltà e della nascente borghesia. Da un punto di vista musicale si assiste a interessanti e reiterati tentativi di superare le forme più o meno stereotipate del melodramma settecentesco e di approfondire alcune situazioni sceniche che già avevano attirato l’attenzione di musicisti ‘riformatori’ come Jommelli e Traetta. Cherubini intende creare una commistione tra l’elemento virtuosistico e quello sentimentale, commovente senza far mancare i tratti buffi. E così se Donna Rosa e Donna Lisetta sono entrambe caratteri seri e si mantengono costanti in tutti i loro interventi, i protagonisti maschili prospettano una più ampia P 8 gamma di sfumature: da Don Pistacchio meraviglioso baritono buffo, che dunque ha anche la necessità di essere un bravo attore, a Don Martino, tenore, che spesso interviene con momenti piuttosto sentimentali e per il quale non mancano virtuosismi e passaggi di coloratura. La concertazione è sempre molto accurata, con un’orchestra costantemente attenta a rimarcare i momenti salienti della vicenda, e si evidenzia in particolar modo nella scena introduttiva e nei due finali impostati con una progressione esemplare di crescente tensione che esplode ora in un delirio divertente con effetti parodistici, ora in una conclusione ‘a sorpresa’ nella quale è contenuta anche tutta la morale della storia. Se la partitura nel suo complesso può essere ricondotta a schemi ricorrenti e riconoscibili, alcuni particolari segnalano un distacco dalle convenzioni melodrammatiche. La densità di certi passaggi, ad esempio, denota una scrittura insolita; il melodizzare di molte frasi, impostate su schemi irregolari, lascia trapelare una preminenza armonica; l’impiego di alcuni procedimenti orchestrali assolutamente inconsueti per la scelta mirata dei timbri (ad esempio il corno inglese impiegato originariamente nelle arie di Donna Lisetta del secondo atto «Ah no, non piangere più» e «Dolce fiamma del mio core»), le successioni di armonie poco ortodosse e la preminenza ricorrente dell’elemento strumentale sottolineano i tratti di uno stile «moderno». Non secondario, infine, l’uso della parodia, evidente soprattutto nelle scene della follia o della morte, dell’ombra o dell’oracolo. In lontananza pare di ascoltare gli echi dello stile di Paisiello e di Galuppi alla cui opera «L’inimico delle donne», rappresentata in Venezia nel 1771, Cherubini pare ispirarsi in particolare modo, ma nel contempo si individuano presagi dello stile rossiniano. Cherubini è pronto, a questo punto, per spiccare il volo dapprima verso i teatri inglesi, dove sarà applau- dito per circa due anni grazie a due nuove opere, e, a partire dal 1786, per quelli francesi, dove conoscerà fama e ammirazione crescenti, almeno sino al 1813, anno de Les Abencérages, ultimo suo avvicinamento al teatro serio. Perfettamente calato nella nuova atmosfera parigina, il Fiorentino aderisce appieno ai modelli operistici locali, abbandonando del tutto l’idea di trasporre in francese opere in italiano. Con Démophoon, andato in scena nel Théâtre de l’Opera nel 1788 e Lodoïska rappresentato al Théâtre Feydeau nel 1791, durante l’ultimo anno di gestione dell’amico fraterno Giovanni Battista Viotti, porta a compimento un programma compositivo personale elaborato sulla scia di Gluck, ma presentato in una forma ancora più coerente e drammatica, prediligendo uno stile essenziale, ma pregnante e volto a sottolineare lo sviluppo del dramma. Le successive affermazioni (in particolare di Médée) gli aprono le porte dei teatri viennesi e lo facilitano nei numerosi incontri professionali (si pensi a Haydn e a Beethoven) che sanciranno in modo inequivocabile i suoi meriti artistici. Mariateresa Dellaborra 9 efore moving to France, where he would dedicate himself entirely to opera seria and, more importantly, he would create new forms of entertainment that would set an example for the European operatic world, Luigi Cherubini (1760-1842) was long active in Italy. There he devoted himself to the genres in vogue, using in an original and rather autonomous way the traditional stylistic features and writing patterns which audiences liked and singers easily mastered. During those years he composed serious and comic titles according to the precise ratio suggested by his teacher Giuseppe Sarti. Between 1780 and 1784, when he left for England, in fact, Cherubini produced as many as eight operas (seven serious and one buffa); among them Lo sposo di tre, marito di nessuna, performed in Venice at the San Samuele theatre in the autumn of 1783. The work, according to what the author himself reported, was quite well received, not only because of the entertaining plot developed by Filippo Livigni, but also because of some inventive effects introduced in the music. The audience’s interest was captured right from the opening symphony, with its brilliant writing enriched by Lombard rhythms, complex orchestral texture and wonderful melodic creativity pivoting on two main themes, the second of which amply developed and varied. Cherubini himself liked this passage so much that he re-used it, preceded by an Adagio, in another opera dated 1798, L’hôtellerie portugaise, following a practice that is not common in his output. The story of Lo sposo unravels according to the best tradition of 18th-century opera, blending elements typical of Neapolitan opera buffa with others from Commedia dell’arte: deceptions, disguises, misunderstandings, ghost scenes, processes and duels, all devised to create hilarious situations. Taken from Carlo Goldoni’s La bottega del caffé (1736), the story of Don Pistacchio, Baron of Lagosecco (‘Drylake’), husband-to-be of Baroness Donna Rosa but, in the end, left a bachelor, puts on stage all the characters typical of Italian opera buffa, people coming from different social classes, whose personalities are well defined: Donna Lisetta, the sister of Captain Don Martino and a Baroness herself; Don Martino, also in search of a wife; Don Simone, uncle of Don Pistacchio; Bettina, a girl who sings in the squares of towns and villages; and Folletto, a trickster. Events and characters follow one another at a breakneck pace, but not without a few pauses in between to comment on love or offer thoughts of a general nature; caricatures and veiled satires are thrown in for good measure. Don Pistacchio is the caricature of the wealthy and conceited but simple-minded country gentleman; Don Simone and Don Martino are figures taken from Commeda dell’arte: the former a sort of Pantalone, the latter a typical gentleman. Also the two actors, Folletto and Bettina, whose main role is that of generating confusion, come from the same artistic milieu. Donna Lisetta and Donna Rosa, instead, are serious and sentimental characters with humorous overtones who help to underline the ultimate meaning of the story: a satire of the matrimonial customs of the small nobility and budding bourgeoisie. From the musical point of view we must note interesting and repeated attempts to supersede the more or less stereotype forms of 18th-century melodrama and concentrate on some particular situations, as already done by ‘reforming’ musicians such as Jommelli and Traetta. Cherubini tries to blend the virtuosic element with the sentimental one, without foregoing the comical aspect. And so while Donna Rosa and Donna Lisetta are serious characters and act as such throughout the opera, the male characters show a wider range of nuances: Don Pistacchio is a wonder- B 10 ful baritone buffo, and his interpreter thus needs to be also a good actor; Don Martino, a tenor, is often entrusted, instead, with sentimental pages and with passages rich in virtuosity and coloratura. The orchestral accompaniment is always accurate, with the instruments constantly underlining the important moments of the story, especially in the introductory scene and in the two finales, where the excellent escalation of tension is released the first time in an amusing explosion of comic effects, the second in an unexpected conclusion that contains the moral of the story. Even though Cherubini’s writing on the whole resorts to well-known devices, in a few details it does depart from operatic conventions. Unusual, for instance is the density of certain passages; and in the line of many phrases, built on irregular patterns, harmony prevails over melody; other features of his «modern» style are some uncommon orchestral developments due to precise choices of timbre (for example the English horn in Donna Lisetta’s second act arias Ah no, non piangere più and Dolce fiamma del mio core), sequences of unorthodox harmonies and the frequent prominence of the instrumental element. The use of parody, finally, is not of secondary importance, as is clear in the scenes of folly and of the oracle. In the distance one seems to hear the echo of Paisiello’s and Galuppi’s styles; Galuppi’s L’inimico delle donne in particular, performed in Venice in 1771, appears to have inspired Cherubini. At the same time, however, there are anticipations of Rossini’s writing. Thus Cherubini was ready to sail away, first towards English theatres, where he would reap success for two years with two new operas; and, from 1786, towards French ones, where his fame would swell at least until 1813, year of Les Abencérages, his last serious opera. Perfectly at ease in the Parisian atmosphere, the composer from Florence adopted the local operatic models, abandoning the idea of transposing Italian operas into French. With Démophoon, which was staged at the Théâtre de l’Opera in 1788, and Lodoïska, performed at the Théâtre Feydeau in 1791, the last year of his dear friend Giovanni Battista Viotti’s management, Cherubini brought to completion a personal artistic path developed on the wake of Gluck but in a form that was even more consistent and dramatic, favouring a style that was essential but meaningful and intended to underline dramatic developments. His further successes (in particular that of Médée) opened the doors of the Viennese theatres to him and helped him in his many professional liaisons (for example Haydn and Beethoven), confirming his artistic merits. Mariateresa Dellaborra (Translated by Daniela Pilarz) 11 evor sich Luigi Cherubini (1760-1842) seinem französischen Schicksal anvertraute, das dazu führen sollte, daß er sich zur Gänze dem ernsten Repertoire widmete und vor allem, daß er Aufführungsformen ins Leben rief, die innovativ und für die europäische Opernwelt beispielhaft waren, hatte der Komponist eine lange italienische Epoche. Darin befaßte er sich mit den Genres, die damals en vogue waren und wandte – wenn auch auf originelle und eher autonome Weise – die traditionellen Stilformen und kompositorischen Merkmale an, wie sie vom Publikum geschätzt wurden und von den Sängern gut assimiliert worden waren. Bei dieser Tätigkeit wechselten komische und ernste Werke einander gemäß den Geboten von Maestro Giuseppe Sarti in präzisem Rhythmus ab. Zwischen 1780 und 1784, dem Jahr seiner Abreise nach England, bringt Cherubini ganze acht Opern heraus, darunter Lo sposo di tre, marito di nessuno, die im Herbst 1783 in Venedig am Teatro San Samuele gegeben wurde. Der Komponist selbst berichtet von einem großen Erfolg, und zwar nicht nur wegen des unterhaltsamen Librettos von Filippo Livigni, sondern vor allem wegen gewisser neuer Effekte des musikalischen Teils. Gleich zu Beginn erregte die sinfonia das Interesse der Hörer durch ihren um lombardische Rhythmen bereicherten brillanten Charakter, die Dichte der Orchesterbehandlung und den gelungenen melodischen Einfall, der ganz auf zwei genau umrissenen Hauptmotiven aufbaute, deren zweites weitläufig entwickelt und variiert war. Cherubini selbst hatte soviel Wohlgefallen an diesem Stück, daß er es mit einem vorausgehenden Adagio-Satz in einer anderen Oper (L’hôtellerie portugaise von 1798) wieder verwendete, was einer in seinem Werkkatalog nicht üblichen Praxis entspricht. Die Handlung von Lo sposo wird auf der Grundlage der im Musiktheater des 18. Jahrhunderts am häufigsten eingesetzten Mittel entwickelt und verschmilzt typische Elemente der neapolitanischen Buffooper mit Passagen der commedia dell’arte: Täuschungen, Verkleidungen, Mißverständnisse, Geisterszenen, Prozesse und Duelle, die alle Situationen von belustigender Komik bewirken sollen. Abgeleitet aus Carlo Goldonis La bottega del caffé (1736), sieht die Geschichte von Don Pistacchio, Baron von Lago Secco, Anwärter auf eine Heirat mit der Baronin Donna Rosa, aber am Ende mit keiner der Frauen verheiratet, auf der Bühne die typischen Rollen der italienischen Buffooper agieren. Sie kommen aus verschiedenen sozialen Schichten und werden entsprechend ausgeprägt charakterisiert: Donna Lisetta, Baronin und Schwester des Hauptmanns Don Martino, der auch eine Ehefrau finden will; Don Simone, Onkel von Don Pistacchio; die Straßensängerin Bettina und der Taschenspieler Folletto. Situationen und Figuren folgen wirbelartig aufeinander, wobei weder Betrachtungen über die Liebe und Prinzipien universeller Natur vernachlässigt, noch Karikaturen und versteckte Satiren beiseite gelassen werden. Ist Don Pistacchio als Karikatur des vermögenden, aufgeblasenen, aber wenig klugen Mannes vom Land angelegt, so sind Don Simone und Don Martino zwei von der commedia dell’arte hergeleitete Charaktere – ersterer ist wie Pantalone, letzterer der typische Kavalier. Auch das Schauspielerpaar Folletto und Bettina, das vor allem dazu da ist, um Verwirrung in die Geschichte zu bringen, stammt aus dem selben künstlerischen Umfeld. Donna Lisetta und Donna Rosa hingegen sind ernste, gefühlvolle Figuren mit komischem Einschlag, die dazu beitragen, den eigentlichen Sinn dieser Geschichte hervorzuheben – die Satire der Heiratsbräuche des niederen Adels und des in Entstehung befindenden Bürgertums. Vom musikalischen Standpunkt her nehmen wir an interessanten, wiederholten Versuchen teil, die mehr oder weniger stereotypen Formen der Oper des 18. B 12 Jahrhunderts zu überwinden und einige szenische Situationen zu vertiefen, die bereits die Aufmerksamkeit von Reformmusikern wie Jommelli und Traetta auf sich gezogen hatten. Cherubini möchte eine Mischung des virtuosen mit dem gefühlvollen und rührenden Element schaffen, ohne daß die buffonesken Züge fehlen sollen. Wenn Donna Rosa und Donna Lisetta beide ernste Charaktere sind und sich in all ihren Nummern nicht verändern, so zeigen die männlichen Protagonisten eine umfangreichere Skala von Nuancen: Von Don Pistacchio, einem wunderbaren Buffobariton, der somit auch ein guter Schauspieler sein muß, bis zu dem Tenor Don Martino, der häufig eher gefühlvolle Stellen hat, und bei dem Virtuosität und Koloraturpassagen nicht fehlen. Es wird immer sehr sorgfältig konzertiert, mit einem Orchester, das ständig darauf achtet, daß die wichtigen Momente der Geschichte herausgestrichen werden. Besonders deutlich wird das in der einleitenden Szene und in den beiden Finali, die mit einer beispielhaften Progression wachsender Spannung angelegt sind, die einmal in einem unterhaltsamen Taumel mit parodistischen Effekten, dann wieder in einem Überraschungsschluß explodieren, in dem auch die ganze Moral der Geschichte enthalten ist. Kann die Partitur in ihrer Gesamtheit auf häufige und erkennbare Schemata zurückgeführt werden, so markieren einige Details eine Entfernung von den Regeln der Oper. Die Dichte gewisser Passagen weist beispielweise eine unübliche Schreibweise auf; die Melodisierung vieler auf unregelmäßigen Schemata aufgebauter Phrasen läßt einen Vorrang der Harmonik durchscheinen; die Verwendung einiger absolut unüblicher Orchestrierungsmomente mit ihrer gezielten Farbwahl (zum Beispiel das ursprünglich verwendete Englischhorn bei den Arien der Donna Lisetta im zweiten Akt «Ah no, non piangere più» und «Dolce fiamma del mio core»), die Abfolge wenig orthodoxer Harmonien und der wiederholte Vorrang des instrumentalen Elements unterstreichen die Züge eines «modernen» Stils. Nicht zweitrangig ist schließlich der Einsatz der Parodie, der vor allem in den Szenen mit Wahnsinn oder Tod, Schatten oder Orakel, deutlich wird. Es scheint, als hörten wir aus der Ferne das Echo des Stils eines Paisiello und Galuppi, an dessen 1771 in Venedig aufgeführter Oper «L’inimico delle donne» sich Cherubini speziell zu inspirieren scheint; gleichzeitig ist eine Vorahnung von Rossinis Stil festzustellen. Nun ist Cherubini bereit, zunächst an die englischen Opernhäuser zu gehen, wo er mit zwei neuen Werken rund zwei Jahre lang Erfolg haben sollte. Ab 1786 ist er in Frankreich, wo er steigenden Ruhm und Bewunderung genießen sollte, was mindestens bis 1813 anhielt, dem Jahr von Les Abencérages, seiner letzten Komposition für das ernste Genre. Der Florentiner hat sich der neuen Pariser Atmosphäre perfekt angepaßt und folgt gänzlich den dortigen Vorbildern, sodaß er davon Abstand nimmt, italienische Werke ins Französische zu übertragen. Mit Démophoon, 1788 im Théâtre de l’Opéra uraufgeführt, und Lodoïska von 1791 im Théâtre Feydeau während des letzten Direktionsjahres seines brüderlichen Freundes Giovanni Battista Viotti, bringt Cherubini ein im Soge Glucks erarbeitetes persönliches Kompositionsprogramm zur Vollendung, das in einer noch konsequenteren und dramatischeren Form vorgelegt wird, die einen essentiellen Stil bevorzugt, der aber prägnant und darauf ausgerichtet ist, die Entwicklung des Dramas zu unterstreichen. Die späteren Erfolge (im besonderen von Médée) öffnen ihm die Tore der Wiener Opernhäuser und erleichtern ihm die zahlreichen Treffen mit Komponistenkollegen (man denke an Haydn und Beethoven), die seine künstlerischen Verdienste unmißverständlich bekräftigen sollten. Mariateresa Dellaborra (Übersetzung: Eva Pleus) 13 vant d’entreprendre son aventure française, qui allait l’amener à se consacrer pleinement au répertoire serio et surtout à donner naissance à des formes de spectacle novatrices et paradigmatiques pour le monde de l’opéra européen, Luigi Cherubini (1760-1842) vécut une longue et intense période italienne pendant laquelle il s’employa à composer des genres en vogue à l’époque, en appliquant – bien qu’avec originalité et autonomie – les tournures et les caractères compositionnels traditionnels appréciés du public et bien assimilés par les chanteurs. Durant cette période, il alterna les titres sérieux et comiques suivant en cela les préceptes de Giuseppe Sarti. Entre 1780 et 1784, année de son départ pour l’Angleterre, Cherubini acheva donc huit opéras (sept de genre serio et un de genre buffo), parmi lesquels Lo sposo di tre, marito di nessuna, donné au théâtre San Samuele de Venise à l’automne 1783. D’après ce que nous en dit l’auteur lui-même, le succès fut assuré non seulement par le comique de l’intrigue de Filippo Livigni, mais aussi et surtout par certains effets inédits de la partie musicale. Dès l’ouverture, la symphonie déclencha l’intérêt des spectateurs par son brillant enrichi de rythmes lombards, la densité du traitement orchestral et l’invention mélodique – particulièrement réussie – basée sur deux motifs principaux bien définis, le second étant plus longuement développé et varié. Cherubini était si satisfait de cette page musicale qu’il la réutilisa, précédée d’un mouvement Adagio, dans une autre œuvre composée en 1798, L’hôtellerie portugaise, faisant là une entorse à son habitude. L’intrigue de Lo sposo repose sur les moyens traditionnels du théâtre musical du dix-huitième siècle, l’auteur y mêlant intimement des éléments typiques de l’opera buffa napolitaine et des passages de la commedia dell’arte : ruses, déguisements, équivoques, scènes spectrales, procès, duels sont tous conçus pour donner naissance à des situations hilarantes. Tirée de La bottega del caffé (1736) de Carlo Goldoni, l’histoire de Don Pistacchio – baron de Lagosecco et aspirant époux de la baronne Donna Rosa, mais qui se retrouve à la fin sans aucune épouse – met en scène les rôles typiques de l’opera buffa italienne. Les classes sociales sont variées et les caractères bien définis ; on y trouve pêle-mêle : Donna Lisetta, baronne et sœur du capitaine Don Martino, lui aussi à la recherche d’une épouse ; Don Simone, oncle de Don Pistacchio ; Bettina la chanteuse de foire et Folletto le prestidigitateur. Les situations et les personnages se succèdent à un rythme effréné sans négliger les réflexions sur l’amour et les maximes de nature universelle et sans éviter les caricatures et les satires voilées. Si Don Pistacchio est la caricature du campagnard fortuné et bouffi d’orgueil, mais peu avisé, Don Simone et Don Martino sont deux caractères inspirés de la commedia dell’arte – le premier, comme Pantalone et le second, chevalier typique – à l’instar du couple Folletto et Bettina, qui interviennent surtout pour créer le désordre au sein de l’intrigue. Donna Lisetta et Donna Rosa sont en revanche des personnages sérieux et sentimentaux, avec quelques touches comiques qui concourent à souligner le sens véritable de l’histoire : la satire des conventions matrimoniales de la petite noblesse et de la bourgeoisie naissante. D’un point de vue musical, l’on assiste à plusieurs tentatives intéressantes d’aller au-delà des formes plus ou plus stéréotypées du mélodrame du dix-huitième siècle et d’approfondir des situations scéniques qui avaient déjà attiré l’attention de musiciens “réformateurs ” comme Jommelli et Traetta. Cherubini veut mélanger l’élément virtuose, sentimental et émouvant sans négliger les traits comiques. Et si Donna Rosa et Donna Lisetta sont toutes deux des caractères sérieux A 14 et constants tout au long de leurs interventions, les personnages masculins offrent une plus vaste gamme de nuances : de Don Pistacchio, merveilleux baryton buffo qui doit donc être bon acteur, au ténor Don Martino, qui intervient souvent avec des passages assez sentimentaux et doit parfois affronter des passages virtuoses et de colorature. L’orchestration est toujours très soignée et ne manque pas de souligner les moments saillants de l’intrigue, notamment dans la scène introductive et dans les deux finales développés suivant une progression exemplaire de tension croissante qui explose tantôt en un délire comique d’effets parodiques tantôt en une conclusion “surprise ” qui renferme toute la morale de l’histoire. Si la partition dans son ensemble peut se rattacher à des schémas reconnaissables, quelques détails marquent une certaine indépendance par rapport aux conventions mélodramatiques. La densité de plusieurs passages, par exemple, dénote une écriture insolite ; la mélodie de certaines phrases, basées sur des schémas irréguliers, laisse percer une prééminence harmonique. L’emploi de quelques procédures orchestrales absolument originales en ce qui concerne le choix des timbres (par exemple le cor anglais utilisé à l’origine dans les arias de Donna Lisetta au second acte, “Ah no, non piangere più” et “Dolce fiamma del mio core”), les successions d’harmonies peu orthodoxes et la prééminence répétée de l’élément instrumental soulignent les traits d’un style “moderne ”. Quant à la parodie, particulièrement évidente dans la scène de la folie ou de la mort, de l’ombre ou de l’oracle, elle joue un rôle d’importance. Tout cela évoque le style de Paisiello et de Galuppi – dont l’opéra “L’inimico delle donne”, représenté à Venise en 1771, semble avoir particulièrement inspiré Cherubini – mais laisse également présager le style de Rossini. Désormais, Cherubini est prêt à prendre son envol pour l’étranger : d’abord les théâtres anglais, où il sera applaudi pendant environ deux ans grâce à deux nouveaux opéras puis, à partir de 1786, les scènes françaises qui lui apporteront une célébrité et une admiration croissantes, du moins jusqu’en 1813, année de Les Abencérages, sa dernière œuvre de genre serio. Parfaitement à son aise dans son nouveau monde parisien, le musicien florentin adopte les modèles lyriques locaux et abandonne totalement l’idée de transposer en français des œuvres écrites en italien. Avec Démophoon, mis en scène au Théâtre de l’Opéra en 1788, et Lodoïska, donné en 1791 au théâtre Feydau – dirigé cette année-là encore par son ami fraternel Giovanni Battista Viotti –, Cherubini achève un programme compositionnel personnel élaboré dans le sillage de Gluck, mais présenté sous une forme encore plus cohérente et dramatique, optant pour un style dépouillé mais prégnant qui souligne le développement du drame. Les œuvres qui suivent (notamment Médée) lui ouvrent les portes des théâtres viennois et facilitent les nombreuses rencontres professionnelles (par exemple avec Haydn et Beethoven) qui confirmeront pleinement ses mérites artistiques. Mariateresa Dellaborra (Traduit par Cécile Viars) 15 Rosa Anna Peraino (Donna Rosa), Giulio Mastrototaro (Don Pistacchio) 16 Maria Laura Martorana (Donna Lisetta) 17 V. Priante (Don Simone), R. A. Peraino (Donna Rosa), E. D’Aguanno (Don Martino) 18 Vito Priante (Don Simone), Rosa Sorice (Bettina), Gabriele Ribis (Folletto) 19 Martino torna a corteggiare Donna Rosa, approfittando della sua delusione. Don Simone però vuol vederci chiaro e lo fa su due piedi, smascherando l’inganno. Tra Simone, la Baronessa, Lisetta e Martino che litigano, Don Pistacchio non capisce più niente, la sua mente sembra far naufragio. Chiede a Martino se il ritratto mostratogli non fosse quello di Lisetta, e l’uomo conferma; ma anche la Baronessa reclama di sapere quale ritratto è stato mostrato, e Martino con abilità scambia ritratto via via che li mostra all’uno e all’altra. Lisetta ora chiede a Martino di vendicare l’affronto sfidando a duello Don Pistacchio. Martino chiede a Pistacchio di rispettare l’impegno. Lisetta affronta la rivale, ed entrambe reclamano il diritto sullo stesso sposo. Ne nasce un ennesimo litigio. TRAMA Primo Atto Nella piazza di Lago Secco si celebra il giorno delle nozze del Barone Don Pistacchio. C’è molta gente per strada, tra cui Folletto, che fa’ giochi di prestigio, e la donna che ama, Bettina, cantante di piazza. In paese sono arrivati anche Donna Lisetta, Baronessa, e suo fratello Don Martino, capitano di fanteria. L’uomo mostra alla sorella un ritratto che gli è stato consegnato da Donna Rosa, anch’essa Baronessa, promessa sposa di Don Pistacchio. Il capitano ha un conto aperto con lei: avrebbe dovuto sposarla ma Donna Rosa gli ha preferito Don Pistacchio, ed ora è pronta la vendetta. Sostituirà il ritratto con quello di sua sorella Lisetta. Don Pistacchio sicuramente se ne innamorerà e lui avrà finalmente campo libero. Lisetta si ritira nella locanda mentre Don Pistacchio esce dal palazzo con un corteo di gente. Incontrato Don Martino, questi si dichiara ambasciatore di Donna Rosa e gli mostra il ritratto di Lisetta. Don Pistacchio si lascia andare a lauti apprezzamenti e le manda a dire, tramite Don Martino, che venga subito. Lo scopo sembra raggiunto, ma accade un contrattempo. Ecco infatti avanzare Donna Rosa, la giusta promessa sposa, giunta alla locanda coi suoi servitori. Il primo ad incontrarla è Don Simone, zio di Don Pistacchio. Sopraggiunge intanto anche Lisetta, che riconosce la Baronessa. Chi non la riconosce, invece, è proprio Don Pistacchio, che indirizza le sue attenzioni solo verso Lisetta, la donna del ritratto, credendola la sua sposa. Donna Rosa, visibilmente irritata, si ritira nella locanda. Rimasti soli, Pistacchio e Lisetta si scambiano parole d’amore. La donna mette in guardia il Barone: non accetterà tradimenti, altrimenti sono pronte quattro schioppettate, preannunciate da uno squillo di tromba. Nel frattempo nella locanda Don Secondo Atto Nel palazzo baronale Don Pistacchio e Don Simone discutono dell’accaduto. Don Pistacchio non vuole più sposarsi, ma accetta l’idea dello zio di rivolgersi a due celebri avvocati di Napoli per avere qualche buon consiglio. Nascosti, Folletto e Bettina ascoltano tutto e architettano un piano contro Don Pistacchio. Folletto corre in cerca di Lisetta e Martino, mentre Bettina finge di acconsentire alla corte di Don Simone. Arrivano gli Avvocati: sono Lisetta e Martino travestiti. Pistacchio li accoglie con riverenza e si lascia incantare dal loro vortice di parole ed equivoci, che lo lascia stordito come sempre. Donna Rosa, nel frattempo, è decisa a tornarsene a casa, ma Don Simone ha un’idea: non potrebbe sposarla lui, invece di Don Pistacchio? La Baronessa accetta, animata dal desiderio di vendetta contro Don Pistacchio e Martino. Ma quest’ultimo riuscirà a farle cambiare idea con un discorso sulla gelosia. Intanto Lisetta e Pistacchio discutono; sopraggiunge Martino con un messaggio della Baronessa: sarà la Sibilla Cumana a decidere chi sarà la sposa di Don Pistacchio. Si recano tutti al tempio 20 c della Sibilla. Folletto si finge Sibilla e annuncia che non ci sarà nessun matrimonio, lo sposo rimarrà zitello. Don Pistacchio, irato, si allontana. Tornata la quiete Martino svela tutto a Donna Rosa: è stato lui ad ordire l’inganno per riconquistare il suo amore. Arriva Don Simone, deciso a reclamare la Baronessa. Rosa e Martino, architettano ora un ultimo inganno. La donna, fingendo amorosa dedizione, si allontana al braccio di Don Simone verso la festa già preparata. Don Pistacchio, che non vuole rassegnarsi a rimanere solo, ora propone il matrimonio a Bettina, che finge di accettare. Sopraggiunge Lisetta, che annuncia le nozze tra la Baronessa e Don Simone: stupito, Pistacchio cambia ancora una volta idea; ora vuole sposare Lisetta, rivale della Baronessa, sempre per far dispetto alla Sibilla. Al banchetto nuziale, i protagonisti ritrovano infine ciascuno l’amato. Quando Don Simone chiede di stringere la mano della Baronessa, lei la concede a Don Martino; quando Don Pistacchio cerca quella di Lisetta, lei la dà a Don Simone; a Don Pistacchio non resta che Bettina, ma lei però si rivolge a Folletto. Pistacchio, sposo di tre, resterà marito di nessuna. THE PLOT Act One The square of the town of Lago Secco (“Dry Lake”) is crowded with people, who have gathered to celebrate the wedding of Baron Don Pistacchio. Folletto, a trickster, is entertaining them with his beloved Bettina, a singer. Also Baroness Donna Lisetta and her brother Don Martino, an infantry Captain, have arrived in town. The man shows his sister a portrait given to him by Donna Rosa, herself a Baroness and Don Pistacchio’s bride-to-be. Martino has an account to settle with the woman, for she rejected his marriage proposal and favoured Don Pistacchio; so Martino has planned his revenge: he will substitute her portrait with that of his sister Lisetta. Don Pistacchio will certainly fall in love with her and Martino will be able to marry Donna Rosa. Lisetta goes into the Inn just as Don Pistacchio comes out of his palace with a retinue of people. Don Martino introduces himself as the ambassador of Donna Rosa, and shows Pistacchio the portrait of Lisetta. The Baron praises the beauty of what he thinks is his future bride and sends Don Martino to tell her that he eagerly awaits her arrival. The goal seems accomplished; but Donna Rosa herself arrives unexpectedly at the Inn, with her retinue of servants. She first meets Don Simone, Pistacchio’s uncle; then Lisetta, who recognises her; Pistacchio, on the other hand, doesn’t, and courts only Lisetta, the lady of the portrait, whom he believes to be his bride. Donna Rosa, offended, storms out. Left alone, Lisetta and Pistacchio exchange words of love. She warns the Baron: she will not tolerate any betrayals, on pain of rifle shots, announced by the sound of a trumpet. Meanwhile inside the Inn Don Martino is courting again Donna Rosa, taking advantage of her disappointment in Pistacchio. Don Simone, though, has sensed that something is suspicious and 21 gets to the bottom of the matter, uncovering the deception. A quarrel ensues among Simone, Donna Rosa, Lisetta and Martino, as Don Pistacchio looks on flabbergasted. He asks Martino if the portrait he showed him was that of Lisetta, and the man confirms it; when the Baroness demands to see it too, he dexterously exchanges it with hers. Lisetta now asks Martino to avenge her by challenging Pistacchio to a duel. Martino asks Pistacchio to keep his promise and marry Lisetta. Lisetta confronts her rival and both claim to have a right to marry Pistacchio. Another quarrel ensues. storms out. Martino now decides to reveal to Donna Rosa that he organised the whole deception, to win back her love. Together, they plan a last ruse. Donna Rosa, pretending to be in love, walks off arm in arm with Don Simone to the prepared wedding banquet. Don Pistacchio, who does not want to remain without a bride, proposes to Bettina, who pretends to accept. Enters Lisetta, who announces the marriage of the Baroness and Don Simone: stunned, Pistacchio changes his mind again; now he wants to marry Lisetta, Donna Rosa’s rival, to spite the Sibyl. At the wedding banquet, finally, each of the protagonists finds his or her own partner: when Don Simone formally asks the hand of the Baroness, she gives it to Martino; when Don Pistacchio seeks that of Lisetta, she gives it to Don Simone; only Bettina remains, but she goes to Folletto. So Pistacchio, with three potential brides, will remain unmarried. Act Two In Pistacchio’s palace the Baron and Don Simone discuss the events. Don Pistacchio does not want to get married any more, but then accepts his uncle’s suggestion to seek the advice of two renowned lawyers from Naples. In hiding, Folletto and Bettina overhear their conversation and scheme another ruse against Don Pistacchio. While Folletto rushes out in search of Lisetta and Martino, Bettina pretends to give in to Don Simone’s courting. But here come the lawyers: they are Lisetta and Martino in disguise. Pistacchio welcomes them with reverence and falls for their wouldbe learned language and whirlwind of words, which leave him, once again, confused. Donna Rosa, in the meantime, has decided to return to Naples, but Don Simone has an idea: would she marry him, instead of Don Pistacchio? The Baroness accepts, to spite Pistacchio and Martino. But the latter succeeds in making her change her mind, with a lecture on jealousy. Meanwhile Lisetta and Pistacchio quarrel; Martino arrives with a message from the Baroness: the Cumaean Sibyl will decide whom Don Pistacchio is to marry. They all go to the temple, where Folletto, acting as the Sibyl, announces that no marriage will take place, Don Pistacchio is to remain single. Pistacchio 22 Liebesworte. Die Dame warnt den Baron, daß sie keinen Betrug akzeptiert, denn in diesem Fall kommt es zu vier Büchsenschüsse, denen ein Trompetenstoß vorausgeht. Inzwischen macht Don Martino in der Herberge der enttäuschten Donna Rosa den Hof. Don Simone will aber Klarheit und deckt die List stante pede auf. Als Simone, die Baronin, Lisetta und Martino streiten, versteht Don Pistacchio gar nichts mehr und glaubt, verrückt zu werden. Er fragt Martino, ob das ihm gezeigte Porträt wirklich Lisetta zeigte, und Martino bestätigt das. Die Baronin will aber auch wissen, welches Porträt hergezeigt wurde, und Martino wechselt geschickt die Porträts aus, je nachdem, wem er sie gerade zeigt. Lisetta fordert Martino nun auf, die Beleidigung zu rächen, indem er Don Pistacchio zum Duell fordert. Martino verlangt von Pistacchio, daß er seine Verpflichtung einhält. Lisetta tritt der Rivalin entgegen, und beide beharren auf ihrem Recht auf den selben Bräutigam. Daraus ergibt sich ein weiterer Streit. DIE HANDLUNG Erster Akt Auf dem Hauptplatz von Lago Secco wird der Hochzeitstag des Barons Don Pistacchio gefeiert. Viele Menschen sind auf der Straße, darunter der Taschenspieler Folletto und die Frau, die er liebt, nämlich die Straßensängerin Bettina. Auch die Baronin Donna Lisetta und ihr Bruder Don Martino, Hauptmann der Infanterie, sind im Ort eingetroffen. Don Martino zeigt seiner Schwester ein Porträt, das er von der Baronin Donna Rosa, der Verlobten Don Pistacchios, erhalten hat. Der Hauptmann hat noch eine offene Rechnung mit ihr zu begleichen, denn er hätte sie heiraten sollen, doch Donna Rosa hat ihm Don Pistacchio vorgezogen, und nun ist er bereit zur Rache. Er wird das Porträt mit dem seiner Schwester Lisetta vertauschen. Don Pistacchio wird sich sicherlich darin verlieben, und der Weg für Don Martino wird endlich frei sein. Lisetta zieht sich in die Herberge zurück, während Don Pistacchio mit einem Rattenschwanz von Leuten sein Palais verläßt. Als er Don Martino trifft, erklärt dieser, er sei Donna Rosas Botschafter und zeigt ihm das Porträt Lisettas. Don Pistacchio ergeht sich in großer Bewunderung und bittet sie über Don Martino, sofort zu ihm zu kommen. Das Ziel scheint erreicht, als etwas dazwischen kommt, denn nun erscheint die richtige Verlobte Donna Rosa mit ihren Bedienten in der Herberge. Als erster trifft Don Simone, Don Pistacchios Onkel, auf sie. Inzwischen erscheint auch Lisetta, die die Baronin erkennt. Wer sie hingegen nicht erkennt, ist Don Pistacchio, der seine Aufmerksamkeiten nur an Lisetta richtet, die Dame auf dem Porträt, die er für seine Verlobte hält. Die sichtlich irritierte Donna Rosa zieht sich in die Herberge zurück. Allein geblieben, tauschen Pistacchio und Lisetta Zweiter Akt Im Baronspalais besprechen Don Pistacchio und Don Simone die Vorfälle. Don Pistacchio will nicht mehr heiraten, nimmt aber den Vorschlag seines Onkels, bei zwei berühmten neapolitanischen Anwälten Rat einzuholen, an. Folletto und Bettina, die sich versteckt hatten, hören alles und hecken einen Plan gegen Don Pistacchio aus. Folletto geht auf die Suche nach Lisetta und Martino, während Bettina vorgibt, zuzustimmen, daß ihr Don Simone den Hof macht. Nun treffen die Anwälte ein – es handelt sich um die verkleideten Lisetta und Martino. Pistacchio empfängt sie mit Ehrerbietung und läßt sich von ihrem Strudel von Worten und Doppelsinnigkeiten betäuben. Inzwischen hat Donna Rosa beschlossen, nach Hause zurückzukehren, aber Don Simone hat einen Einfall: könnte nicht er sie heiraten, anstelle von Don Pistacchio? Die 23 Baronin nimmt den Vorschlag an, da sie sich an Don Pistacchio und Martino rächen will. Letzterem gelingt es aber, sie mit einer Rede über die Eifersucht davon abzubringen. Inzwischen diskutieren Lisetta und Pistacchio. Nun trifft Martino mit einer Botschaft der Baronin ein: die Sibylle von Cumä wird entscheiden, wer Don Pistacchios Frau wird. Alle begeben sich zum Tempel der Sibylle. Folletto gibt sich als Sibylle aus und verkündet, daß es zu keiner Hochzeit kommen wird; der Bräutigam bleibt Junggeselle. Der erzürnte Don Pistacchio verläßt die Stätte. Nachdem die Ruhe wieder eingekehrt ist, entdeckt Martino Donna Rosa alles: er hat die List gesponnen, um ihre Liebe wiederzuerringen. Nun kommt Don Simone, der entschieden ist, die Hand der Baronin zu erbitten. Rosa und Martino hecken jetzt eine letzte List aus. Rosa täuscht liebevolle Hinneigung vor und entfernt sich am Arm Don Simones, um sich auf das schon vorbereitete Fest zu begeben. Don Pistacchio, der sich nicht damit abfinden will, daß er allein bleibt, schlägt nun Bettina die Heirat vor; diese tut so, als ob sie den Vorschlag annähme. Jetzt kommt Lisetta, welche die Hochzeit zwischen der Baronin und Don Simone ankündigt. Pistacchio ist verwundert und ändert nochmals seinen Sinn; nun will er Lisetta, die Rivalin der Baronin, heiraten, um die Sibylle zu ärgern. Beim Hochzeitsschmaus findet jeder der Protagonisten endlich den geliebten Partner. Als Don Simone um die Hand der Baronin bittet, gibt diese sie Don Martino; als Don Pistacchio nach der Hand Lisettas sucht, gibt diese sie Don Simone. Don Pistacchio bleibt nur mehr Bettina, doch diese wendet sich an Folletto. Pistacchio, der Verlobte von dreien, ist der Mann von keiner. INTRIGUE Acte premier Sur la place de Lago Secco, l’on s’apprête à célébrer les noces du Baron Don Pistacchio. Dans la foule rassemblée se trouvent le prestidigitateur Folletto et la femme qu’il aime, Bettina, chanteuse sur les places. Au village sont arrivés aussi la Baronne Donna Lisetta et son frère Don Martino, capitaine d’infanterie. Ce dernier montre à sa sœur un portrait que vient de lui remettre Donna Rosa, Baronne elle aussi et future épouse de Don Pistacchio. Le capitaine est en compte avec elle : il aurait dû l’épouser mais Donna Rosa lui a préféré Don Pistacchio. Il compte se venger en remplaçant le portrait de Donna Rosa par celui de sa sœur Lisetta. Assuré que Don Pistacchio s’éprendra d’elle, il pense ainsi avoir le champ libre. Lisetta s’est retirée à l’auberge tandis que Don Pistacchio sort du palais avec sa suite. Il rencontre Don Martino qui déclare être l’ambassadeur de Donna Rosa et lui montre le portrait de Lisetta. Don Pistacchio exprime toute son admiration et demande à Don Martino de lui amener sa promise sur le champ. L’objectif semble donc être atteint, mais un fâcheux contretemps survient : l’on voit arriver Donna Rosa, la véritable fiancée, arrivée elle aussi à l’auberge avec ses serviteurs. Le premier à la voir est Don Simone, l’oncle de Don Pistacchio. Puis survient Lisetta, qui reconnaît la Baronne. En revanche, Don Pistacchio ne la reconnaît pas et accorde toute son attention à Lisetta, la femme du portrait, qu’il croit être sa future épouse. Donna Rosa, visiblement irritée, retourne à l’auberge. Demeurés seuls, Don Pistacchio et Lisetta échangent des mots d’amour. La jeune femme met le Baron en garde : elle n’acceptera aucune incartade de la part de son époux ; au cas où celui-ci oublierait sa promesse, il recevrait quatre coups de fusils annon24 cés par le son d’une trompette. Pendant ce temps, dans l’auberge, Don Martino recommence à faire la cour à Donna Rosa, profitant de sa déception. Mais Don Simone veut y voir plus clair et dévoile bien vite la tromperie. Simone, la Baronne, Lisetta et Martino se querellent tous ; Don Pistacchio n’y comprend rien, il lui semble que sa tête éclate. Il demande à Martino si le portrait qu’il lui a montré n’est pas celui de Lisetta, et l’homme le lui confirme ; quant à la Baronne, elle exige de savoir quel portrait lui a été montré, mais Martino échange avec beaucoup d’adresse les portraits au fur et à mesure qu’il les montre à l’un ou à l’autre. Lisetta souhaite que Martino venge l’affront subi en provoquant Don Pistacchio en duel. Martino demande à Pistacchio de respecter son engagement. Lisetta affronte sa rivale et toutes deux finissent par clamer leur droit sur le même époux. Une querelle éclate encore. Martino. Mais ce dernier parvient à la faire changer d’idée en lui parlant de jalousie. Pendant ce temps, Lisetta et Pistacchio discutent ; survient Martino porteur d’un message de la Baronne : le choix de l’épouse de Don Pistacchio est désormais entre les mains de la Sibilla Cumana. Tous vont au temple de la Sibylle. Folletto feint d’être la Sibylle et annonce qu’il n’y aura aucun mariage et que le futur époux restera vieux garçon. Courroucé, Don Pistacchio quitte les lieux. Lorsque le calme est revenu, Martino avoue à Donna Rosa qu’il est l’auteur de la tromperie échafaudée pour reconquérir son amour. Don Simone les rejoint, bien intentionné à réclamer la main de la Baronne. Rosa et Martino imaginent alors un dernier stratagème : simulant des sentiments d’amour, elle se dirige au bras de Don Simone vers la fête préparée pour les noces. Don Pistacchio, qui ne se résigne pas à rester seul, demande à Bettina de l’épouser, ce qu’elle feint d’accepter. Survient Lisetta, qui annonce les noces entre la Baronne et Don Simone. Surpris, Pistacchio change encore une fois d’idée : il veut maintenant épouser Lisetta, rivale de la Baronne, afin de contrarier la Sibylle. Au banquet nuptial, les protagonistes retrouvent tous l’élu/l’élue de leur cœur. Quand Don Simone demande à serrer la main de la Baronne, celle-ci la donne à Don Martino ; quand Don Pistacchio cherche celle de Lisetta, elle l’accorde à Don Simone ; Don Pistacchio doit alors se tourner vers Bettina, mais celle-ci donne sa main à Folletto. Pistacchio, époux de trois femmes, ne sera en fin de compte le mari de personne. Acte deuxième Dans le palais du Baron, Don Pistacchio et Don Simone discutent des événements. Don Pistacchio ne veut plus se marier, mais accepte l’idée de son oncle de faire appel aux conseils de deux célèbres avocats de Naples. Cachés, Folletto et Bettina entendent tout et échafaudent un plan contre Don Pistacchio. Folletto court chercher Lisetta et Martino tandis que Bettina feint d’être flattée par la cour que lui fait Don Simone. Les Avocats arrivent : ce sont Lisetta et Martino déguisés. Pistacchio les accueille avec respect, se laissant charmer par leur tourbillon de paroles savantes et équivoques qui l’étourdissent comme toujours. Pendant ce temps, Donna Rosa s’est décidée à rentrer chez elle, mais Don Simone a une idée : ne pourrait-elle pas l’épouser à la place de Don Pistacchio ? La Baronne accepte, mue par un désir de vengeance à l’égard de Don Pistacchio et 25 Giovanni Paisiello Luigi Cherubini LO SPOSO DI TRE E MARITO DI NESSUNA PROSERPINE Drama in three acts Libretto by Nicolas François Guillard (THRICE BETROTHED, NEVER WED) LIBRETTO Dramma giocoso in due atti Libretto di Filippo Livigni 1 Sinfonia 1 Sinfonia ATTO PRIMO ACT ONE Scena I Amena pianura del Villaggio di Lago Secco. Da un lato Palazzo Baronale, dall’altro Locanda con insegna. In prospetto varie colline ed altre villerecce abitazioni. Folletto fra molti villani facendo giochi ai bussolotti, D. Simone a sedere guardandolo con meraviglia, e Bettina in atto di suonare il salterio. First Scene The pleasant countryside around the village of Dry Lake. On one side the Baron’s Palace, on the other an Inn. In the distance, hills and country houses. Folletto surrounded by peasants, entertaining them with tricks. Don Simone, sitting and watching him in amazement, and Bettina, playing a zither. 2 Simone – Guardate quanti giochi che fa quel ciarlatano! É destro assai di mano, strasecolar mi fa. Folletto – Passa, sparisci e vola, in man non ci ho più niente, ecco la verità. Or dunque dove sta? E pur quella figliuola (a Bettina che cava la palla di saccoccia) l’ha in tasca, e non lo sa. Simone/ Folletto/ Bettina – Ah, ah, ah, ah, ah, ah. Son cose da far ridere, gran gioco è questo qua. Bettina – Allegri, piazza piazza, che adesso col salterio vi vuol questa ragazza spassare col cantar. Simone/ Folletto – Silenzio qui si faccia, e stiamo ad ascoltar. Bettina – Se viene il mio diletto, gli dico via di qui; che amor per te, furbetto, mi fa languir così. Ah, ih, ah, ih, ah, ih. 2 Simone – Look at all the tricks that charlatan can play! He’s incredibly skilful, I’m quite astonished. Folletto – Go, disappear and fly away, and my hands are empty, it’s all true. Where is it now? That girl has it in her pocket and doesn’t know it. (to Bettina, who produces a marble from her pocket) Simone/ Folletto/ Bettina – Ha, ha, ha, ha, ha, ha. How amusing, what a great trick. Bettina – Cheer up, people, for now, playing her zither, this girl will entertain you with a song. Simone/ Folletto – Let’s quiet down and listen. Bettina – If my sweetheart comes near me I tell him: go away; for loving you, rogue, just causes me to suffer. Ah, ih, ah, ih, ah, ih. 27 Che amor per te, furbetto, mi fa languir così. Simone/ Folletto – Che bella canzoncina, mi piace, signor sì. Simone/ Folletto/ Bettina – Viva lo sposo con l’allegria, in festa e giubilo qui si starà. Vada in malora l’ipocondria che sempre offende la sanità. 3 Facciamo più guadagno noi altre ragazzette cantando canzonette per piazza e per città: a questo un’occhiatina, un vezzo, un riso a quello: e il caro scioccarello che crede a’ nostri detti ci fa dei regaletti, e allegraman si sta. (Esce) For loving you, rogue, just causes me to suffer. Simone/ Folletto – Nice little song, I like it, yes indeed. Simone/ Folletto/ Bettina – Hurrah for the groom and for happiness, we shall make merry and have fun. Down with hypochondria, which offends sanity. 3 There is quite of a profit to be made for us girls by singing silly songs in squares and villages: a little wink at one, a caress and a smile to another: and the dear simpletons believe all that we tell them and give us presents, and we are happy. (She leaves.) Scena II D. Lisetta da viaggio, con D. Martino vestito da Uffiziale. Scene II Donna Lisetta in travel attire, with Don Martino dressed as an Officer. 4 Lisetta/ Martino – Bella cosa ch’è il viaggiare, desta al core l’allegria, lo fa proprio saltellare, lo fa tutto giubilar. Tocca, tocca postiglione, suona, suona la cornetta, mi consola, mi diletta, sempre allegra/o mi fa star. 5 Martino – Sorella mia, giudizio; il concertato già s’è detto fra noi: ecco il ritratto. (Cava di saccoccia un ritratto) Con questo e un po’ d’astuzia, 4 Lisetta/ Martino – Travelling is wonderful, it fills one’s heart with happiness, it makes it jump with joy, it makes it jubilant. Whip, whip, postillion, play, play the cornet, it cheers me up, delights me, keeps me in high spirits. 5 Martino – Right then, sister; we are agreed: here is the portrait. (produces a portrait from his bag) With it and a little cunning 28 la mia e la tua sorte io voglio fare. Lisetta – Ma l’impegno, fratel, grande mi pare. Martino – Amor mi assisterà. La Baronessa se ardì per uno sciocco di ricusare il mio sincero affetto pur mia sposa esser deve a suo dispetto. Lisetta – Amor lo faccia pure. Martino – Io già ti dissi che questo Don Pistacchio... Lisetta – É un uomo sciocco. Martino – E che la Baronessa, Donna Rosa... Lisetta – Sua destinata sposa... Martino – Mi manda apposta qui per far vedere a questo Cavaliere il suo ritratto. Lisetta – Onde in vece di quello... Martino – Il tuo gli mostrerò. Lisetta – E se gli piace? Martino – Io giuro sopra Marte il mio campione ch’io sposo Donna Rosa, e tu il Barone Lisetta – Da ridere mi viene. Martino – Orsù, Lisetta, torna nella locanda e lascia fare a me. Lisetta – Ma se per sorte là Donna Rosa giunga? Martino – Usa scioltezza già lei non ti conosce. Lisetta – Dici bene. Martino – Vanne, più non tardar, cara sorella. Lisetta – Fammi presto saper buona novella. (Esce) Martino – Son nell’impegno affè. Ma quanta gente qui discende dal palazzo! Al gran corteggio, al modo di vestire, al portamento, dev’essere il Baron. Martino attento. I will make your fortune and mine. Lisetta – But the enterprise, brother, seems difficult. Martino – Love will assist me. The Baroness fell for a dolt and rejected my sincere love, but shall be my bride in spite of herself. Lisetta – May Love make it possible. Martino – As I told you this Don Pistacchio... Lisetta – Is a fool. Martino – And the Baroness, Donna Rosa... Lisetta – His bride to be... Martino – Has sent me here to show her portrait to said gentleman. Lisetta – And instead... Martino – I will show him yours. Lisetta – And if he likes it? Martino – I swear upon Mars, my champion, that I will marry Donna Rosa, and you the Baron. Lisetta – This will be fun. Martino – And now, Lisetta, go to the Inn and leave it to me. Lisetta – What if by chance Donna Rosa shows up there? Martino – Act naturally, she doesn’t know you. Lisetta – Of course. Martino – Go, tarry no longer, dear sister. Lisetta – Bring me good news and soon. (She leaves.) Martino – The task is difficult indeed. But look at all the people coming out of that palace! Judging from the large retinue, the way they man is dressed and carries himself, it must be the Baron. Watch out, Martino. 29 Scena III Don Pistacchio vestito pomposamente con Domestici e Vassalli appresso con Memoriali in mano, e detto. Scene III Don Pistacchio in pompous attire with Servants and Retainers carrying petitions, and Martino. 6 Pistacchio – Or che son vestito in gala fate largo o Parigini, tanti tanti Burattini voi sembrate accanto a me. Son ben fatto, e ben tagliato, son galante, e petrimè. La natura m’ha formato con lo Stampo Fransuè. 7 Orsù Villani da me cosa volete? Grazie? Giustizia? E ben, da me l’avrete. Buon vecchio, cosa vuoi? T’hanno ammazzato l’asino? Non importa, tutti abbiam da morire. Un contadino cavò gl’occhi al tuo bue? Che gli faccia gli occhiali a spese sue. Tu non hai da mangiar? Digiuna, e zitto. Tu hai debiti? Paga. Cosa dici? Tua moglie sen fuggì? Fuggi tu ancora. Piano... adagio.... in malora... la mia testa voi fate riscaldar. V’intesi, andate; tutti giustizierem, non dubitate. (Partono i Villani) Martino – (Che caro mammalucco!) Pistacchio – (Chi è costui?) Devo servirla a niente? Martino – Mi conosce? Pistacchio – Non ho questa fortuna, o mio Signore. Martino – A voi ne vengo come ambasciatore. Pistacchio – E chi vi manda a me? Martino – La vostra sposa. Pistacchio – La Baronessa? Martino – Appunto. 6 Pistacchio – Now that I am smartly dressed move aside, Parisians, you are rag dolls in comparison. I am good looking and well dressed, gallant and kind. Nature cast me in the French mould. 7 Right then, peasants, what do you want from me? Grace? Justice? You’ll get them. Good old man, what do you want? They killed your ass? No matter, we all must die. A farmer blinded your ox? He shall pay for glasses. You have nothing to eat? Then fast, and shut up. You are full of debts? Pay them. What’s that? Your wife ran away? Do the same. Easy... easy... what the hell! My head is bursting. I heard you, now go; we’ll give everyone their due, don’t worry. (The peasants leave.) Martino – (What a charming dolt!) Pistacchio – (Who is this man?) What can I do for you? Martino – Do you know me? Pistacchio – I haven’t the good fortune, Sir. Martino – I have come to you as an ambassador. Pistacchio – And who sends you? Martino – Your bride. Pistacchio – The Baroness? Martino – That’s right. 30 Pistacchio – Oh questa è bella! Presto un comodo qui. Siedi, e favella. (I Servi portano da sedere, e Martino siede) Martino – La nobile, galante e valorosa Baronessa sua sposa, per grave affare a te oggi m’invia, dal messo impara il messagger qual sia. Pistacchio – (Oh qua sì che m’imbroglio. Eh via coraggio, e si risponda al messagger di maggio.) Conciosiacosachè virgola, e punto... Verbigrazia... cioè... anzi lei sappia, che quando in queste arene verrà l’amato bene acclamata sarà da’ miei vassalli a suono di rocchette, e scarcavalli. Martino – (Costui rider mi fa.) Ella, Signore, prima di metter piede in questa terra per togliere ogni guerra vuol ch’esamini bene il suo ritratto. Eccolo: se v’aggrada pronta qui ne verrà: se non v’alletta al patrio suol ritornerà di fretta. Pistacchio – Bella, bella, bellissima, formosa, formosissima. Martino – Vi piace? Pistacchio – Oh, che bel naso! Che bocca maestosa! Martino – Osservi bene la grazia, la bellezza, il brio, la gentilezza: e de’ suoi pregi ecco il pregio efficace, sotto il ciglio ben nero occhio vivace. Pistacchio – Oh che occhio, oh che occhio! Favorisca, come si chiama lei? Martino – Io, Don Martino; famoso Capitan d’Infanteria. Pistacchio – Lei padrone sarà di casa mia. Pistacchio – Oh what a surprise! Bring a chair, quickly. Have a seat and let’s talk. (The Servants bring a chair and Martino sits down) Martino – The noble, lovely and virtuous Baroness, your future wife, has sent me here today on an important mission; learn from the messenger what the sender is. Pistacchio – (Oh, here I get confused. Well, courage, let’s answer this harbinger of love.) Insomuchas, comma, and full stop... Verbi gratia... id est... indeed rest assured when to this land my betrothed will come my servants shall welcome her in full pomp. Martino – (He is truly amusing.) Sir, before she sets foot in your land, to avoid any possible misunderstanding, she wants you to examine her portrait. Here it is: if you like it she will come straightaway; if you don’t she will go home without delay. Pistacchio – Lovely, lovely, gorgeous! shapely, curvaceous. Martino – Do you fancy her? Pistacchio – Oh, what a fine little nose! What a majestic mouth! Martino – Please observe her grace, her beauty, her spirit and gentleness; and of all her qualities here is the most valuable of all: lively eyes under jet black eyelashes. Pistacchio – Oh what eyes, what eyes! Forgive me, what is your name? Martino – My name is Don Martino; famous Infantry Captain. Pistacchio – You shall be the master of my house. 31 Martino – (Questo cercando vo’.) Dunque alla sposa... Pistacchio – Dica, che qui l’aspetto, che il naso, che l’occhietto, m’han bombardato il cor: che un arsenale, un foco in corpo, un caldo del diavolo mi sento da che ho visto il suo ritratto. Martino – In sella postiglioni. (Il colpo è fatto.) 8 Superbo di me stesso andrò con tal novella, della tua sposa bella il core a consolar. Amico già mi pare veder la Baronessa di giubilo a saltare a ridere e ballar. Da bravi, ancora noi balliamo in buona tresca un Taici alla tedesca vogliamo adesso far. La laira, che diletto, la laira, che spassetto, la laira, via girate, la laira, via saltate, la laira, che allegria... Pistacchio – La laira, Vussignoria si vada a far squartar. Martino – Già vado pien di gloria, già monto, sì, a cavallo, ma quando torno il ballo vogliamo seguitar. Martino – (That’s what I want.) Then your bride... Pistacchio – Tell her that I wait for her, that her nose and lively eyes have knocked me out: that I feel an arsenal, a fire inside me, a heat of hell, after seeing her portrait. Martino – Prepare my horse, groom. (It’s done.) 8 Proud of my accomplishment I’ll go with such great news to brighten up the heart of your fair bride. Friend, I can already picture the Baroness jumping for joy, laughing and dancing. Come on, let us also dance a lively Tresca in German style, let’s twirl around. La laira, what delight, la laira, what fun, la laira, turn around, la laira, hop, la laira, what happiness... Pistacchio – La laira, get lost, your Lordship. Martino – Here I go full of glory, yes, I jump on horseback, but when I return we shall resume our dance. Scena IV Don Simone, indi la Baronessa Rosa da viaggio, con seguito di Servitori. Scena IV Don Simone, the Baroness Rosa in travel attire, with her retinue of Servants. 9 Baronessa – (É questa la locanda? É dunque questo 9 Baroness – (Is this the Inn? That, then, 32 del Barone il palazzo? Ah, che impaziente attendo il Capitan secondo il patto, per sentir come accolse il mio ritratto.) Simone – (Cospetto, e che bel tocco!) Baronessa – (Chi mai sarà costui.) Simone – (Mi guarda!) Baronessa – (Si confonde.) Simone – (Parmi che sia perplessa.) Baronessa – (Forse il Baron?) Simone – (Forse la Baronessa?) Baronessa – (Domandiamo.) Simone – (S’ accosta.) Baronessa – Serva sua. Simone – Son io suo servitore. Baronessa – Scusi di tanto ardir, chi è lei, Signore? Simone – Del Baron Don Pistacchio io sono il Pistacchione, cioè sono suo zio, Don Simeone. Baronessa – (Spiacemi questo incontro! Il Capitano non vedo ancora in queste vicinanze.) (Agitandosi per la scena.) Simone – (Costei mi par che balla contradanze.) Baronessa – É vero che tra poco la sposa del Barone qui s’attende? Simone – Sì Madama. Baronessa – Ma come! Se principio non vedo ancor di feste! Simone – Son preparate già; e poi, Signora, la sposa qui da noi non giunse ancora. Baronessa – E se mai fosse giunta? Simone – Sarebbe una sorpresa strepitosa. Baronessa – Più occultarmi non vuo’, io son la sposa. (Con gravità.) Simone – La sposa? Benvenuta. Oh che felice incontro, oh che allegrezza. Mio nipote a chiamar vo’ con prestezza. is the house of the Baron. Ah, I’m impatient to meet the Captain, as agreed, to know if he liked my portrait.) Simone – (Goodness gracious, what a fine figure of a woman!) Baroness – (I wonder who that man is.) Simone – (She’s looking at me!) Baroness – (He’s growing confused.) Simone – (She seems puzzled.) Baroness – (Could he be the Baron?) Simone – (Could she be the Baroness?) Baroness – (Let’s ask him.) Simone – (She’s coming this way.) Baroness – Your servant. Simone – Your most humble servant. Baroness – Forgive my asking, Sir, who are you? Simone – Baron Don Pistacchio’s senior relative, that is to say his uncle, Don Simeone. Baroness – (I don’t like this encounter! The Captain is nowhere to be seen yet.) (Pacing restlessly) Simone – (She seems to have the fidgets.) Baroness – Is it true that soon the Baron’s bride is to arrive? Simone – Yes, Madam. Baroness – Well! I don’t see any feast being prepared! Simone – That’s because it’s ready; and, Madam, the bride has not arrived yet. Baroness – What if she has? Simone – It would be a fantastic surprise. Baroness – I’ll won’t hide it any longer, I am the bride. (Gravely.) Simone – The bride? Welcome. Oh what a lucky encounter, what happiness! I’ll call my nephew right away. 33 10 Gioia bella un tantino aspettate Don Pistacchio qui adesso verrà: fate festa, suonate, ballate che la sposa è venuta di già. Viva, viva gridate ragazzi; villanelle qua tutte correte; uova fresche e galline se avete, per omaggio portatele qua. (Entra.) 10 My jewel, wait just a little moment, Don Pistacchio will be here presently; make merry everyone, play, dance, for the bride has arrived. Cheer, lads; come here, lasses; if you have any fresh eggs or hens, bring them as presents. (He leaves.) Scena V Donna Lisetta con seguito, e detta, poi Don Pistacchio. Scene V Donna Lisetta with her retinue, and the above, then Don Pistacchio. 11 Lisetta – (Lisetta allegramente. A Don Pistacchio già consegnò Martino il suo ritratto; or coraggio ci vuole, il colpo è fatto.) Baronessa – (Grand’aria che ha costei!) Lisetta – (La Baronessa credo, che quella sia.) Baronessa – (Che bell’umore!) Lisetta – (Comincia un poco a palpitarmi il core.) Pistacchio – Presto paggi, staffieri, squadronatevi tutti per le scale, ch’io faccio intanto il mio cerimonale. Baronessa – (Eccolo!) Lisetta – (Questo è d’esso!) Pistacchio – (Una di queste due dev’esser la mia sposa: un po’ vediamo se quel ritratto mi parlò verace. (Guardando Donna Lisetta) Ecco il ciglio ben nero, l’occhio vivace.) Lisetta/ Baronessa – (Mi guarda! Voglio fargli riverenza.) (Fan riverenza al Barone.) Baronessa – (Ma quale confidenza ha con quella il Barone!) Dico, sa lei, 11 Lisetta – (All is well, Lisetta. Don Pistacchio has already been given the portrait by Martino; with a little courage now, the deed is done.) Baroness – (What a haughty lady!) Lisetta – (I believe she must be the Baroness.) Baroness – (What mood!) Lisetta – (My heart is beginning to throb.) Pistacchio – Pages, footmen, hurry, line up along the stairway, while I formally welcome her. Baroness – (There he is!) Lisetta – (It must be him!) Pistacchio – (One of those two must be my bride: let’s see if the portrait was truthful. (Studying Donna Lisetta) There are the jet black eyelashes and lively eyes.) Lisetta/ Baroness – (He’s looking at me! Let’s curtsey.) (They both curtsey to the Baron.) Baroness – (How familiar she appears to be with the Baron!) Pardon me, 34 che la sua sposa è qua? Pistacchio – Lo so di sicuro. Baronessa – E tarda tanto, a farle un complimento? Pistacchio – Se son venuto a posta. Baronessa – E ben sentiamo. Pistacchio – (A Lisetta) (Madama, se vi amo, ve lo dica il rossor della mia pelle: le vostre luci belle m’hanno fatto restar qual Marcantonio. Consolatemi voi col matrimonio.) Lisetta – (Ah ah voi siete un bocconcin di sposo avvenente, compito e concettoso.) Pistacchio – (Alla Baronessa) Lei è stata servita. Baronessa – Di che cosa? Pistacchio – Di che? Del complimento. Baronessa – Ma se parlato non avete ancora. Pistacchio – (Ora comprendo, è sorda la Signora.) Baronessa – (Questo mi pare un matto.) Pistacchio – Eccomi a lei... Baronessa – No: parlate con me. Pistacchio – Ma la mia sposa... Baronessa – La vostra sposa merta più rispetto. Pistacchio – Dunque mi lasci fare il mio dovere. Lisetta – (Questo equivoco assai mi da piacere.) Baronessa – Lo vedeste il ritratto? Pistacchio – Adesso vengo. Baronessa – A me, a me badate. Pistacchio – L’ho veduto. Baronessa – E vi piacque? Pistacchio – Moltissimo. Baronessa – Dunque se vi gradì, perché non fate alla sposa un saluto, un’accoglienza? Pistacchio – (Con questa sorda io perdo la pazienza.) Lisetta – (Io fingo, e rido.) Baronessa – Che! Siete ammutito? Ah sì, che quel silenzio do you know that your bride is here? Pistacchio – I do indeed. Baronessa – And how long will she have to wait before you pay her a compliment? Pistacchio – I’m here for that purpose. Baronessa – Well then, let’s hear it. Pistacchio – (To Lisetta) (Madam, the blush on my cheeks will tell you that I love you: the beauty of your eyes has rendered me comatose. Revive me with marriage.) Lisetta – (Ha, ha, what a delectable spouse you are, handsome, polite and fertile in thought.) Pistacchio – (To the Baroness) There you are. Baroness – What do you mean? Pistacchio – What do I mean? The compliment. Baroness – But if you haven’t said a word. Pistacchio – (I see, the lady is hard of hearing.) Baroness – (He must be crazy.) Pistacchio – Here I am Madam... Baroness – No: talk to me. Pistacchio – But my bride... Baroness – Your bride deserves more respect. Pistacchio – Then let me do my duty. Lisetta – (This misunderstanding is quite amusing.) Baroness – Have you seen the portrait? Pistacchio – One moment. Baroness – Pay attention to me. Pistacchio – I have. Baroness – And did you like it? Pistacchio – Very much. Baroness – Well, if you liked it, why don’t you offer your bride a word of greeting, of welcome? Pistacchio – (This deaf lady is trying my patience.) Lisetta – (Let’s go along and have some fun.) Baroness – What! Have you lost your tongue? Ah! Your silence 35 conoscer più mi fa che non l’amate. Andate, o donne, andate, a quest’uomini falsi a prestar fede. Pazza é colei che in voi si fida e crede. 12 Chi crede a voi altr’ uomini bugiardi, ed ingannevoli fra pene, affanni e spasimi meschina sempre sta. Avete un cor durissimo con noi non siete stabili, il vostro amor è perfido e pien di falsità. Così con questi barbari parlar bisogna o femmine, l’avere un cor di zucchero del danno assai ci fa. (Entra nella locanda.) tells me that you don’t love her. Ah, women, believe me, men are false and don’t deserve our trust. Only a fool can have confidence in them. 12 She that has faith in you, men, liars and deceivers as you all are, shall suffer and pine away and be forever miserable. You have a stony heart, you are not truthful, your love is wicked and full of deceptions. Those barbarians, women, deserve this sort of talk, to be sweet with them is not worth it. (She enters the Inn.) Scena VI Lisetta, e Don Pistacchio. Scena VI Lisetta, and Don Pistacchio. 13 Pistacchio – Quella Signora è matta, o spiritata. Lisetta – Orsù parliamo a noi mi amate sì o no? Pistacchio – Chi lo contrasta! Son Don Pistacchio tuo, e tanto basta. Lisetta – Dunque sposiamci adesso. Pistacchio – Adesso? Andiamo sopra. Lisetta – Però prima dovete giurarmi fedeltà di non tradirmi per qualunque bellezza. Pistacchio – Sì, lo giuro. Lisetta – E se poi mi mancate? Pistacchio – Fatemi dare quattro schioppettate. Lisetta – Pensateci pur ben. Pistacchio – So quel che dico. Lisetta – Voi morirete presto. 13 Pistacchio – That lady is mad, or possessed. Lisetta – So, let’s get back to us: do you love me? Pistacchio – Who says anything to the contrary! I am your Don Pistacchio, and that’s that. Lisetta – Then let’s get married now. Pistacchio – Now? Let’s go inside. Lisetta – But first you must promise that you won’t betray me with any other lady. Pistacchio – Yes, I promise. Lisetta – And if you fail your promise? Pistacchio – You may shoot me a couple rifle shots. Lisetta – Think carefully. Pistacchio – I know what I’m saying. Lisetta – You’ll die young. 36 Pistacchio – La mia fede sarà costante, e forte. Lisetta – E un segno preverrà la vostra morte. Pistacchio – Che segno, quale segno? Lisetta – Un suon di corni l’avviso a voi darà di mia vendetta. Pistacchio – Un suon di corni! Lisetta – Sì. Pistacchio – E lei sposina viene a nozze, e tal suon mi porta in casa? Lisetta – Già ve l’ho detto. Pistacchio – Intesi già, ci siamo. Lisetta – Andiamo dunque in casa. Pistacchio – Andiamo, andiamo. (Partono.) Pistacchio – My faith will be unwavering and strong. Lisetta – And a sign will forewarn you of your death. Pistacchio – A sign, what sign? Lisetta – A sound of horns will alert you of my revenge. Pistacchio – A sound of horns! Lisetta – Yes. Pistacchio – And you, my sweet bride, come to your marriage bringing along such a sound? Lisetta – I’ve warned you. Pistacchio – Well, we’re agreed. Lisetta – Then let’s go inside. Pistacchio – Let’s go, let’s go. (They leave.) Scena VII Baronessa e Don Martino dalla locanda, indi Don Simone. Scene VII The Baroness and Don Martino exiting the Inn, then Don Simone. Baronessa – Ma parlatemi chiaro, in qual maniera da voi lo sposo accolse il mio ritratto. Martino – Alle corte, Madama, egli è un bel matto. Baronessa – Ma come? Martino – Un’altra sposa! Ho già saputo, che cela in propria casa il mezognero. Baronessa – Ah, che il sospetto mio troppo fu vero. Simone – (La sposa ancora è qui!) Mia Baronessa, Don Pistacchio il nipote venne o non venne a tributarvi onore? Baronessa – Don Pistacchio è un ingrato. Martino – Un mancatore. Simone – Il nipote Barone? Baronessa – Sì è un finto. Martino – Un trapolone. Simone – E per qual cosa? Baronessa – Perché cela in sua casa un’altra sposa. Simone – Un’altra sposa? Ah, ah, rider mi fate. Baroness – Look, just say it, how did the intended react to my portrait? Martino – In short, Madam, he’s a madman. Baroness – What? Martino – Another bride! I heard that he hides her in his house, the liar. Baroness – Ah, my suspicions were legitimate. Simone – (The bride, still here!) Baroness, hasn’t Don Pistacchio, my nephew, come to give you his respects? Baroness – Don Pistacchio is an ungrateful man. Martino – A breaker of promises. Simone – My nephew, the Baron? Baroness – Yes, he’s a false man. Martino – A deceiver. Simone – And why? Baroness – He’s hiding another bride in his house. Simone – Another bride? Ha, ha, that’s ludicrous. 37 Baronessa – Se vi dico di sì. Martino – Qui l’ho veduta. Simone – Veduta? Sarà stata un’apprensione. Baronessa – Cospetto! Martino – Cospettone! (Passeggiando con furia) Simone – Cospettone! Ehi, Pistacchio, Pistacchio! Baroness – I’m telling you. Martino – I’ve seen her. Simone – Seen her? You must have dreamed her. Baroness – My goodness! Martino – Goodness gracious! (Pacing furiously) Simone – Goodness gracious me! Hey there, Pistacchio, Pistacchio! Scena VIII Don Pistacchio dal balcone, poi in strada, e detti indi Donna Lisetta. Scene VIII Don Pistacchio from the balcony, then in the street, and the above, then Donna Lisetta. Pistacchio – Eccomi, sono qua. Simone – Parlami chiaro: sopra chi v’è? Pistacchio – La sposa! Nol sapete? Simone – La sposa? Quale sposa? Pistacchio – La sposa ch’è mia sposa. Baronessa – Ah, traditore! Amico, a che tardate? Martino – Adesso gli darò quattro stoccate. Pistacchio – Aiuto, zio Simone. Simone – Lo meriti, briccone. Baronessa – Una mia pari non si tratta così! Martino – Voglio insegnarvi le dame a rispettar. Pistacchio – Questa è pur bella! Ma chi è colei? Simone – Non più; tua moglie è quella. 14 Pistacchio – Moglie quella! Ma di chi? Moglie mia! Ma no, signora; Moglie dentro e moglie fuora quante mogli ho da pigliar? Simone – La tua moglie è questa qui. Pistacchio – La mia moglie oibò sta lì. Martino/ Baronessa – (Se destate i miei furori Pistacchio – Here I am. Simone – Tell the truth: who do you have up there? Pistacchio – My bride! Don’t you know? Simone – Your bride? Which bride? Pistacchio – The bride who is to be married to me. Baroness – Ah, traitor! My friend, what are you waiting for? Martino – I shall run him through with four straight thrusts. Pistacchio – Help, uncle Simone. Simone – You deserve it, you rogue. Baroness – A noblewoman like me treated in such a way! Martino – I’ll teach you to respect ladies. Pistacchio – This is nonsense! Who is she? Simone – Enough; she’s your bride. 14 Pistacchio – She, a bride! Whose bride? My bride? Ah, no, madam; One bride inside, one bride outside, how many brides am I to marry? Simone –Your bride is this one. Pistacchio – My bride, tut–tut, is that one. Martino/ Baroness – (If you make me angry 38 quella testa pronta e lesta or per aria sbalzerà.) Pistacchio – Non si scaldino, signori, sposo questa, sposo quella, ed un’altra se ci sta. Simone/ Baronessa/ Martino – Che contento in core io sento! Giubilar mi fate già. Baronessa – Date a me quella manina. Pistacchio – Sì, carina, eccola qua. (Qui si sentono suonare le trombe) Simone/ Baronessa/ Martino – Ma, pian, che suono è questo? Pistacchio – Son morto, cari amici. Baronessa/ Martino – Scherzate. Simone – Cosa dici? Pistacchio – Son morto, sì signor. Lisetta – All’eco grato, e armonico, di questo suon piacevole, cari miei sposi amabili, goder vi faccia amor. Pistacchio – Ma io però non voglio sposar con sì bel suono, che sempre i corni sono presagio di dolor. Simone/ Baronessa/ Martino – Ma cos’è questo inciampo! Lisetta – (Per voi non v’è più scampo.) Simone/ Baronessa/ Martino – Via su la man porgete. Lisetta – (Son quattro lo sapete) Simone/ Baronessa/ Martino – Barone, a che pensate? Pistacchio – A quattro schioppettate. Simone/ Baronessa/ Martino/ Lisetta/ Pistacchio – (Che imbroglio maledetto. Mi batte in petto il cor. his head will get blown to pieces.) Pistacchio – Don’t get heated, ladies and gentlemen, I’ll marry this one, I’ll marry that one, and a third one too, if I must. Simone/ Baroness/ Martino – What joy I feel in my heart! You’ve made me happy. Baroness – Give me your dear hand. Pistacchio – Yes, beloved, here it is. (A sound of trumpets is heard.) Simone/ Baroness/ Martino – Ho, what sound is this? Pistacchio – I’m as good as dead, my dear friends. Baronessa/ Martino – You’re joking. Simone – What are you saying? Pistacchio – As good as dead, yes, sir. Lisetta – At the welcome and melodious notes of this pleasant sound, dear bride and groom, may love make you happy. Pistacchio – I, however, do not wish to get married to such music, for horns have always been harbingers of grief. Simone/ Baroness/ Martino – What snag is this? Lisetta – (You’re done for.) Simone/ Baroness/ Martino – Come on, give me/her your hand. Lisetta – (Two rifle shots, remember.) Simone/ Baroness/ Martino – Baron, what’s on your mind? Pistacchio – Two rifle shots. Simone/ Baroness/ Martino/ Lisetta/ Pistacchio – (What a terrible mix–up. My heart is pounding. 39 La mia testa in tai momenti vacillando si confonde: come nave in mezzo all’onde combattuta è da più venti: e sdegnato un nembo irato già la porta a naufragar.) (Entrano tutti in casa del Barone) My head is spinning, falters, is confused: it’s like a ship at the mercy of the waves, tossed by the winds; and a furious storm is about to sink her.) (They all go inside the Baron’s house.) Scena IX Camera del Barone. Bettina e Folletto. Scene IX The Baron’s apartment. Bettina and Folletto. 15 Folletto – Chi tiene moneta visetto mio bello da questo e da quello si fa rispettar: e chi non ha soldi si fa strapazzar, da questo e da quello si fa strapazzar. Chi tiene moneta fa sempre convito, e con appetito si spassa a mangiar; e chi non ha soldi digiuno può star. Chi tiene moneta fa bene all’amore, e con le signore si suole spassar: e chi non ha soldi sta solo a crepar. In somma Bettina chi tiene soldetti insino gli orbetti sa fare cantar. (Entrano) 15 Folletto – If a person has money my beautiful darling he gets also everyone’s respect: if a person has no money, instead, he gets mistreated, from everyone he gets mistreated. The man who has money eats well all the time, satisfies his appetite, eats to his heart’s content; The man who has no money goes on an empty stomach. The man with money is lucky in love, and ladies flock around him: the man without money is left all alone. That’s to say, Bettina, that if someone has a long purse he gets everyone ready to serve him. (They leave.) 40 Scena X Lisetta. Scene X Lisetta. 16 Lisetta – Sono amante, e son pietosa, vanto in seno un dolce cuore, sempre in me vi regna amore pace cara e fedeltà. Da quell’alma ancor dubbiosa deh disgombra il reo sospetto, che temer d’un puro affetto, è tiranna crudeltà. (Parte.) 16 Lisetta – I’m a loving and compassionate woman, I have a tender heart where love reigns all the time with peace and faithfulness. Chase from your doubtful soul all dark suspicions, for to fear my pure love is a terrible cruelty. (She leaves.) Scena XI Don Pistacchio, Don Simone, Baronessa, e Don Martino discorrendo fra loro. Scene XI Don Pistacchio, Don Simone, the Baroness, and Don Martino talking to each other. 17 Pistacchio – (Ecco la falsa sposa.) Simone – (In questo punto scacciamola di casa.) Martino – (alla Baronessa) (É qui l’amico.) Baronessa – (Lo vedo, ma mi sembra torbidetto.) Martino – (Avrà, cred’io, sospetto che siate ancor sdegnata.) Pistacchio – Presto parti di qua, donna sfacciata. Baronessa – A me? Pistacchio – A te, Signora bugiarda Baronessa. Baronessa – Ah no: non devo più oltraggi tollerar. Vindice chiamo voi sol de’ torti miei (a Don Martino) Martino – (a Don Pistacchio, cavando la spada) Ben, che facciamo? Pistacchio – Signor zio... Simone – Tocca a te; su via coraggio. Martino – Ponga mano al guantone. Simone – Presto. 17 Pistacchio – (There is the false bride.) Simone – (At this point we must throw her out of our house.) Martino – (to the Baroness) (Our friend is here.) Baroness – (I see him, but he seems wary.) Martino – (He must, I daresay, suspect you to be still angry.) Pistacchio – Get out of here, impudent woman. Baroness – Me? Pistacchio – You, madam, liar of a Baroness. Baroness – Ah no: I shall not tolerate any more insults. I appoint you avenger of my wrongs. (To Don Martino) Martino – (to Don Pistacchio, drawing his sword) Well then, shall we? Pistacchio – Uncle, sir... Simone – It’s your problem; courage, go. Martino – Draw your sword. Simone – Hurry. 41 Pistacchio – Adagio. Mi tolga prima un dubbio Ussignoria: lei della sposa mia non mi portò il ritratto? Martino – Sì, signore. Eccolo: non fu questo? (Gli mostra il ritratto di Lisetta) Pistacchio – Questo appunto; e questo sol mi piace; sotto ciglio ben nero, occhio vivace. Martino – (Si cambi con destrezza.) Veda se questo è il suo. (Alla Baronessa mostrandole il proprio) Baronessa – Sì, questo è il mio. Simone – Con sua licenza, vuò vederlo anch’io. (Vedendo quello della Baronessa) Nipote sei un bel matto: questo non è ritratto che merta i tuoi disprezzi. Pistacchio – Anzi vi ho detto che mi piace da piè fino alla testa. Baronessa – Dunque la sposa io sono. Pistacchio – É quella. Simone – É questa. Martino – E siam da capo. Simone – Hai torto. Pistacchio – Ho torto un cavolo. Che imbroglio del diavolo è mai questo per me! Care mie donne, sposine mie dilette, se tanti intrighi agli uomini portate, serro bottega, e più per me non fate. 18 Donne belle, son fallito, il negozio diseccato, più per voi non fo mercato; mercanzia più non ci sta. Non mi sono ancor sposato Pistacchio – Easy. First dispel a doubt for me, your Lordship: didn’t you show me my bride’s portrait? Martino – Yes, sir. Here it is: isn’t this the one? (He shows him Lisetta’s portrait) Pistacchio – Precisely; and I like only this one; lively eyes under jet black eyelashes. Martino – (Let’s swap it dexterously.) See if it is yours. (To the Baroness, showing her her own) Baroness – Yes, it is mine. Simone – If I may, I’d like to see it too. (Looking at the portrait of the Baroness) Nephew, you are crazy: this is no portrait to be scorned. Pistacchio – On the contrary, I told you that I like it from head to toe. Baroness – Then I am your bride. Pistacchio – My bride is that one. Simone – It’s this one. Martino – Here we go again. Simone – You’re wrong. Pistacchio – Wrong my foot. What a hellish muddle I’ve got into! Dear women, sweet brides, if you give men so many problems, I give up, you’re not for me. 18 Fair ladies, I have gone bankrupt, the shop is empty, I’m no longer available, this ware is not for sale. I haven’t even got married yet 42 ed in casa v’è il demonio, che sarà col matrimonio con due mogli che sarà? Voi siete amabile, quella è vezzosa, voi una vipera, quella gelosa, voi mi volete, mi brama quella. La donna tira in verità, ma io cavallo non son di sella che per la posta correndo va’. Per due donne contentare per finir la gran questione, non dovrei esser Barone, ma di Tunisi un Bassà. (Parte.) and already my house is like hell, what is it going to be when I’m wedded, with two wives? You are lovely, she is pretty, you are a viper, she is jealous, you want me, she yearns me. Women like to be in the saddle but I am no saddle horse to be ridden to exhaustion. To satisfy two women, to put an end to this dispute, I ought to be more than a Baron, I ought to be a great lord. (He leaves.) Scena XII Baronessa, Don Martino, e Don Simone. Scene XII The Baroness, Don Martino, and Don Simone. 19 Baronessa – Mio caro Don Simon. Simone – Caro Don Cancaro; A sentir tante risse io non son uso, e confuso son io, più che confuso. (Parte.) Baronessa – Cosa ne dite voi? Martino – Che Don Pistacchio conoscer non vi vuol per sua consorte. Baronessa – Dunque... Martino – A duello io vuo’ sfidarlo, e a morte. Baronessa – Oh bravo! Martino – E pur Madama per comprovarvi il mio sincero amore sarei pronto a sposarvi a suo rossore. Baronessa – Vendicatemi prima. 19 Baroness – My dear Don Simone. Simone – Dear Don Mayhem, rather; I’m not accustomed to all this commotion, I am confused, befuddled. (He leaves.) Baroness – What do you think? Martino – That Don Pistacchio doesn’t want to marry you. Baroness – Then... Martino – I shall challenge him to a duel, and to the death. Baroness – Oh, good! Martino – And moreover, my lady, to show you my sincere love, I’d be ready to marry you, and thus put him to shame. Baroness – First avenge me. 43 Martino – E poi? Baronessa – E poi, forse vi appagherò. Martino – Zitto, ritorna. Baronessa – Qui mi ritiro intanto, e a voi mi affido. (Si ritira.) Martino – Vendicarvi saprò, di lui mi rido. Martino – And then? Baroness – And then perhaps I’ll grant your wish. Martino – Hush, he’s returning. Baroness – I withdraw and trust in you (She withdraws.) Martino – I will avenge you, I’m not afraid of him. Scena XIII Don Pistacchio, Don Simone che sopraggiungono, e detti. Scene XIII Don Pistacchio and Don Simone arriving, and the above. 20 Martino – Se la bella del ritratto tu non sposi in quest’istante, cava il guanto, fatti avanti, ricomincia a duellar. Pistacchio – Padron caro, io non son matto, quella sola adoro, ed amo; quella cerco, e quella bramo, quella appunto io vo’ sposar. Don Simone – Bravi, bravi, son contento, fatto è già l’aggiustamento; venga pur la Baronessa che le nozze vogliam far. 20 Martino – If you don’t marry the lady of the portrait this instant then draw your sword, come forward, and let’s get on with the duel. Pistacchio – Sir, I’m no such fool, she’s the only one I love and adore; I want her, I yearn for her, indeed I will marry her. Don Simone – Good, good, I’m satisfied, then it’s settled; fetch the Baroness and let’s celebrate the marriage. Scena XIV Lisetta, e la Baronessa per parte opposta, e detti. Scene XIV Lisetta and the Baroness from opposite sides, and the above. Lisetta – Son qua pronta, chi mi chiama? Baronessa – Chi mi brama? Son qua lesta. Pistacchio/ Simone – Una donna sì molesta più di voi non si può dar (Don Pistacchio alla Baronessa e Don Simone a Lisetta). Baronessa – Che baldanza! Lisetta – Che arroganza! Pistacchio/ Simone – Questa vostra è un’imprudenza Lisetta – Here I am, who’s calling me? Baroness – Who wants me? I’m here. Pistacchio/ Simone – A worse pesterer that you was never created. (Don Pistacchio to the Baroness and Don Simone to Lisetta). Baroness – What boldness! Lisetta – What arrogance! Pistacchio/ Simone – You’re being inconsiderate. 44 (come sopra) Martino/ Baronessa/ Lisetta – Ah non ho più sofferenza, che maniera di trattar! Baronessa – Ma mi dica, Signorina, dal mio sposo che pretende? Lisetta – Lei è pazza madamina, Don Pistacchio mio sarà. Pistacchio – Chi è di voi la Baronessa? Baronessa – Io son quella. Lisetta – Quella io sono. Lisetta/ Baronessa/ Pistacchio/ Simone/ Martino – Qui si canta d’un sol tuono, e cadenza non si fa. Lisetta – Guardate che dama, che sposa gentile! La rabbia, la bile mi monta già su. Baronessa – Guardate che sposa che dama avvenente! Gran volpe insolente gran furba sei tu. Lisetta – Rispettami audace. Baronessa – Prudenza fraschetta. Pistacchio/ Simone/ Martino – Gran fiera saetta precipita giù. Lisetta/ Baronessa – Lasciatemi il braccio. Pistacchio/ Martino/ Simone – Che torbido impegno. Lisetta/ Baronessa – Son cieca di sdegno. Pistacchio/ Martino/ Simone – Madame non più. Lisetta/ Baronessa – Tremate, tremate... Pistacchio/ Martino/ Simone – Quel foco smorzate. Lisetta/ Baronessa – Rovina, rovina... Pistacchio/ Martino/ Simone – S’è accesa la mina. Lisetta/ Baronessa – Vendetta, vendetta... Pistacchio/ Martino/ Simone – Gran fiera saetta... Lisetta/ Baronessa/ Pistacchio/ Simone/ Martino – Non tanto furore (As above) Martino/ Baroness/ Lisetta – Ah, I can’t tolerate this, what manners! Baroness – Tell me, young lady, what do you want from my future husband? Lisetta – That’s nonsense, madam, Don Pistacchio will be mine. Pistacchio – Which of you is the Baroness? Baronessa – I am. Lisetta – I am. Lisetta/ Baroness/ Pistacchio/ Simone/ Martino – By singing the same note no music is produced. Lisetta – Oh, the fine lady, the sweet bride! I’m consumed with rage. Baronessa – Oh, the lovely bride, the charming lady! You’re an insolent fox, an out–and–out rogue. Lisetta – Show some respect, bold woman. Baroness – Be careful, you flirt. Pistacchio/ Simone/ Martino – A great flash of lightning is about to strike. Lisetta/ Baroness – Let go of my arm. Pistacchio/ Martino/ Simone – What a predicament. Lisetta/ Baroness – I’m blind with fury. Pistacchio/ Martino/ Simone – Ladies, enough. Lisetta/ Baroness – Tremble, tremble... Pistacchio/ Martino/ Simone – Put out your fire. Lisetta/ Baroness – Ruin, ruin... Pistacchio/ Martino/ Simone – The bomb has exploded. Lisetta/ Baroness – Revenge, revenge... Pistacchio/ Martino/ Simone – A great flash of lightning... Lisetta/ Baroness/ Pistacchio/ Simone/ Martino – Calm down 45 madame non più. Mai tanto il mio core sdegnato non fu. ladies, enough. Never has my heart been more enraged. Scena XVI Lisetta, indi Don Pistacchio, poi Don Martino, indi Don Simone, e Baronessa. Scene XVI Lisetta, then Don Pistacchio, then Don Martino, then Don Simone, and the Baroness. 21 Lisetta – Zeffiretti che placidi e cheti, sussurrate fra questi arboscelli, del mio core i gelosi martelli voi calmate deh per pietà. Pistacchio – Augelletti che garruli, e lieti, qui d’intorno amorosi cantate, alla bella che adoro volate, e con voi portatela qua. Lisetta – Qua son’io furbetto, furbetto. Pistacchio – Furbo no, ma costante amoroso. Lisetta/ Pistacchio – Ah per te più non trovo riposo, più quest’alma la calma non ha. Martino – (Fra la tema, e la dolce speranza si confonde il mio cor poverello; ma se Lisa si sposa con quello, presto, presto lo vuol consolar.) Simone/ Baronessa – (Zitto, zitto, l’abbiamo trovati.) Martino – (Questo arrivo mi spiace un tantino.) Pistacchio – Cara, cara. Lisetta – Carino, carino. Pistacchio/ Lisetta – (Di dolcezza mi sento mancar). Martino/ Simone/ Baronessa – (Dalla rabbia mi sento crepar.) 21 Lisetta – Sweet breezes that peacefully murmur through these saplings, appease the jealous pounding of my heart ah, for pity’s sake! Pistacchio – Birds that cheerfully chirp and sing in these surroundings, fly to the fair lady I adore and bring her here. Lisetta – I am here, silly. Pistacchio – Not silly, but madly in love. Lisetta/ Pistacchio – Ah because of you I cannot rest, this heart has no more peace. Martino – (Torn between hope and distress, my poor heart is confused; but if Lisa marries him soon it will find comfort.) Simone/ Baroness – (Hush, hush, we’ve found them.) Martino – (Their arrival is not welcome.) Pistacchio – Darling, darling. Lisetta – Dear, dear. Pistacchio/ Lisetta – (Love takes my breath away.) Martino/ Simone/ Baroness – (Rage plays havoc with my heart.) 46 CD 2 CD 2 1 Simone – Bada bene ser nipote, se mi metti un piede in fallo, questa testa di metallo con un legno io spaccherò. Baronessa – Bada bene mancatore, vedi qua questo coltello? Se più fai da mattarello, nel tuo cor lo ficcherò. Martino – Se non fate il dover vostro, questa bocca di pistola nelle canne della gola scaricar ve la saprò. Lisetta – Caro sposo vezzosetto, se per quella mi lasciate, delle quattro schioppettate la promessa adempirò. Pistacchio – Schioppettate, la sposina! Legno in testa a mio fratello! Qua pistola, là coltello, glorioso morirò. Martino/ Simone – E così, che decidete? Lisetta/ Baronessa – E così, cosa facciamo? Martino/ Simone – E così, che risolviamo? Lisetta/ Baronessa – Mi sposate sì, o no? Martino/ Simone/ Lisetta/ Baronessa – Decidete, attento/a sto. Pistacchio – Andate alla malora signori quanti siete. Da vero mi volete far pazzo diventar. Martino/ Simone/ Lisetta/ Baronessa – Ma questo... Pistacchio – Non v’ascolto. Martino/ Simone/ Lisetta/ Baronessa – Ma questo... Pistacchio – Non vi sento. Martino/ Simone/ Lisetta/ Baronessa – 1 Simone – Now be careful, nephew, if you take a false step, I’ll club that hard nut of yours until it cracks. Baroness – Now be careful, you liar, do you see this knife? If you keep up this crazy act of yours I’ll drive it into your heart. Martino – If you don’t do your duty I’ll discharge this pistol down the pipes of your throat. Lisetta – My dear husband-to-be, if you leave me for that woman I’ll fulfill that promise of a couple of rifle shots. Pistacchio – Rifle shots from my bride! Beaten up by my uncle! Here a pistol, there a knife, I’ll meet a glorious death. Martino/ Simone – So, what have you decided? Lisetta/ Baroness – So, what shall we do? Martino/ Simone – So, what have we resolved? Lisetta/ Baroness – Will you marry me, yes or no? Martino/ Simone/ Lisetta/ Baroness – Make up your mind, I’m waiting. Pistacchio – Go to the devil, all of you. You have really decided to drive me insane. Martino/ Simone/ Lisetta/ Baroness – But this... Pistacchio – I’m not listening. Martino/ Simone/ Lisetta/ Baroness – But this... Pistacchio – I won’t hear. Martino/ Simone/ Lisetta/ Baroness – 47 Ma questo è un mancamento, l’avrete da pagar. Pistacchio – Mi fanno vacillar. But this is a breach of promise, you will pay for it. Pistacchio – They make me giddy. Scena XVII Bettina, e Folletto che si avanzano dal fondo del giardino, e detti. Scene XVII Bettina and Folletto coming from the back of the garden, and the above. Bettina/ Folletto – Silenzio per finezza, silenzio miei signori; non fate più rumori, che stiamo lì a cantar. Lisetta/ Martino/ Simone/ Baronessa – La rabbia già mi stuzzica. Pistacchio – La testa già mi rotola. Lisetta/ Martino/ Simone/ Baronessa – Baron, Baron giudizio. Pistacchio – Son pazzo, son frenetico. Bettina/ Folletto – Che gran bisbiglio orribile, che cosa mai sarà. Tutti – Mi par sentire un organo con gli alti, e bassi zufoli, e tante voci insolite che cantano qua, e là. I bassi mentre intonano, i due soprani imitano! Oh che dolcezza unisona, oh che soavità! Or tutti par che creschino, or tutti par che calino... adagio... piano... unitevi... non fate no, più strepito... ohimè, che babilonia, che sinagoga è qua. Bettina/ Folletto – Be quiet please, silence, ladies and gentlemen; not a sound, we are here to sing. Lisetta/ Martino/ Simone/ Baroness – My anger is about to boil over. Pistacchio – My head is spinning. Lisetta/ Martino/ Simone/ Baroness – Baron, Baron, be sensible. Pistacchio – I’ve gone mad, I’m seized with a frenzy. Bettina/ Folletto – What a commotion, what can the matter be? Tutti – It’s like an organ playing, with high notes, low notes, flutes, and many strange voices singing with it. The basses strike up, and the two sopranos imitate! Oh, what sweet unison singing, what gentle sounds! One moment they all rise, the next they all drop... easy... slow down... blend... no, not so loud... alas, what a din, what a hubbub. 48 ATTO SECONDO ACT TWO Scena I Gabinetto. Folletto, e Bettina, indi Don Pistacchio e Don Simone. 2 Folletto – Che ne dici Bettina di questa storiella? Bettina – É tanto nuova, e bella, allegra, graziosa, e singolare, che in piazza, affè, potrebbesi cantare. Folletto – Mi par di sentir gente. Bettina – Don Simone qui viene col nipote scioccarello. Folletto – Ritiriamoci qui zitti, e bel bello. (Si ritirano) Pistacchio – No, non voglio più moglie; ho già fissato di morir senza eredi. Simone – Ma la sposa... Pistacchio – Se la prenda chi vuol. Fra questa, e quella, caro signor mio zio, non ho più testa. Simone – E pur senti che idea mi viene nel pensiero. Pistacchio – Via sentiamo. Bettina – (Sentiamo ancora noi.) Simone – Adesso proprio in Napoli spedir vuo’ una staffetta. Pistacchio – Per cosa far? Simone – Per fare qui venire due primari avvocati; onde da loro consiglio prenderemo, e meglio in causa ci regoleremo. Pistacchio – Evvia zio Simone. Simone – Ah, che ti pare? Pistacchio – Mi piace come zucchero il pensiero. Simone – Andiamo in corso a mettere il corriero. Folletto – Sentisti? First Scene A study. Folletto, and Bettina, then Don Pistacchio and Don Simone. 2 Folletto – What do you think, Bettina, of this business? Bettina – It’s so new and nice, cheerful, delightful and unique that we could indeed sing it in the squares. Folletto – I think I hear people coming. Bettina – Don Simone is coming this way with his crazy nephew. Folletto – Hush, let’s withdraw, careful. (They hide.) Pistacchio – No, no more wife; it’s decided, I’ll die without an heir. Simone – But your bride... Pistacchio – Anyone may have her. What with her and the other, my dear uncle, I’ve lost my mind. Simone – But listen to the idea that has dawned in my mind. Pistacchio – Let’s hear it. Bettina – (Let’s hear it too.) Simone – Without delay I’ll send a courier to Naples. Pistacchio – What for? Simone – To summon two famous lawyers; they will advise us, and we’ll know better what to do. Pistacchio – Hurrah for uncle Simone. Simone – So, how do you like it? Pistacchio – Your idea is as sweet as sugar. Simone – Let’s hurry and dispatch the courier. Folletto – Did you hear that? 49 Bettina – Ho inteso tutto. Folletto – La padrona bisogna prevenir di questo affare. Bettina – Sai che non dici mal. Folletto – Qualche regalo forse guadagnerò. Bettina – E la mia parte? Folletto – La tua parte si intende. Bettina – Dunque a lei presto vanne, e cammina. Folletto – Ingegnarsi convien, cara Bettina. 3 Un uomo astuto, e destro scialacqua, e vive bene; di questo son maestro, e scuola posso dar: chi giuoca di cervello con arte, ed impostura, per tutto fa figura, e il mondo fa burlar. Bettina – Everything. Folletto – The lady must be forewarned of this business. Bettina – You know, that’s not a bad idea. Folletto – I may get some reward. Bettina – And what about my share? Folletto – Your share goes without saying. Bettina – Go to her, then, off you go, leave. Folletto – One must be smart, Bettina. 3 A clever and skilful man has money to spend and lives well; I’m a master in this, I can give lessons to anyone: he that uses his brain with cunning and ingenuity, makes always a good impression and makes a fool of everyone. Scena II Bettina, indi Don Simone. Scene II Bettina, then Don Simone. 4 Bettina – Certo, chi è destro al mondo di far fortuna sempre può sperare. Simone – In Napoli il corrier già ho fatto andare. Bettina – Serva vostra, Signor. Simone – Oh bella bella, schiavo, schiavo cor mio. Bettina – Cor mio. Simone – Che serve; già tu lo sai, carina, che son morto per te. Bettina – Voi mi burlate, sono una poverella. Simone – Ma io ricca ti farò Bettina bella. Bettina – (Adesso è tempo.) Ricca? Eh non lo credo. 4 Bettina – Indeed if one is adroit in this world he has a better chance to make his fortune. Simone – I just sent the courier to Naples. Bettina – Your servant, sir. Simone – Oh, you’re a beauty, my heart is in chains. Bettina – My heart. Simone – It’s no use; you already know, my dear, that I pine away for love of you. Bettina – You’re making fun of me, I am a poor girl. Simone – And I will make you rich, fair Bettina. Bettina – (Let’s seize the opportunity.) Rich? Ah, I don’t believe you. 50 Simone – Ricca, ricca, ricchissima. Bettina – Ma veda Vossustrissima, (Cava di saccoccia una borsa vuota) In questa borsa mia non v’è un soldetto. Simone – Hai ragion. Prendi qua, mio dolce amore. (Le dà la sua) Bettina – Comincio adesso a credervi, Signore. Simone – Dammi la tua manina. Bettina – Oh mi vergogno. Simone – Perché? Bettina – Perché arrossisco di mostrarla così senza un anello. Simone – Dunque prenditi questo (Le dà un anello) Bettina – Ah quanto è bello. Simone – Mi vuoi tu ben? Bettina – Sia maledetto... (strofinandosi il naso) Simone – Con chi l’hai? Bettina – L’ho ben con uno stranuto; par che voglia venire e scampa via. Simone – Piglia piglia tabacco, gioia mia. (Cava la scatola) Bettina – Oh grazie. (Prende tabacco) Simone – Tira forte. Bettina – Eccì. Simone – Salute. Bettina – Buono questo tabacco! Simone – É di Siviglia. Ti piace? Non rispondi? Bettina – Io son sincera, mi piacerebbe più la tabacchiera. Simone – Prendi la tabacchiera; e prendi ancora il mio core con tutto l’altro resto. Bettina – Per adesso, Signor, mi basta questo. 5 No, tanto scortese non sono, Signore, quel vostro bel core sta ben dove sta: Simone – Rich, rich, wealthy. Bettina – Look, Your Lordship, (She produces an empty purse) I haven’t a brass farthing in my purse. Simone – You’re right. Here, take this my sweet love. (He gives her his purse.) Bettina – Now I’m beginning to believe you, sir. Simone – Give me your dear little hand. Bettina – Oh, I wouldn’t dare. Simone – Why? Bettina – Because I’m shy to show it, without a ring. Simone – Then take this one. (He gives her a ring.) Bettina – Oh, how beautiful. Simone – Do you love me? Bettina – Damn you... (rubbing her nose) Simone – Who makes you angry? Bettina – A sneeze; it feels like it’s coming and then it goes away. Simone – Here, have some snuff, my darling. (Produces a snuff–box) Bettina – Oh, thank you. (She takes a pinch) Simone – Sniff hard. Bettina – Etchoo. Simone – Bless you. Bettina – Fine snuff! Simone – It’s from Seville. Do you like it? Why aren’t you answering? Bettina – To be sincere, I like the snuff–box better. Simone – The snuff–box is yours then; and also my heart, and all the rest. Bettina – For the moment, sir, this is enough. 5 No, I’m not so impolite, sir, your generous heart is fine as it is: 51 se il mio non vi spiace, vel dono a buon patto, e giusto baratto fra noi si farà. Che dite, volete? Son pronta, pigliate: il vostro a me date, contenta son già. (Che caro babeo, che sciocco amatore.) Non più, che l’amore struggendo mi va’. (Parte) if you like mine I’ll give it to you but on condition that it will be a fair exchange between us. What will you say, do you agree? I am ready, you take mine and give me yours, and I’ll be happy. (What a dear simpleton, what a dumb suitor.) Ah enough, love is consuming me. (She leaves.) Scena III Sala con sedie. Don Pistacchio, indi un servo, poi Don Simone. Scene III A hall with some chairs. Don Pistacchio, then a servant, then Don Simone. 6 Pistacchio – Signor zio, signor zio. Presto vedete Don Simone dov’è, dov’è ficcato. (Smanioso) Simone – Perché gridi così, sei spiritato? Pistacchio – Son giunti, son venuti. Simone – Chi è venuto? Pistacchio – I dottori, cospetto, gli avvocati. Simone – Oh bravo. E dove sono? Pistacchio – Per le scale. Simone – Ad incontrarli andiamo. Pistacchio – Ecco già entrano. Simone – Che aria maestosa! Pistacchio – Mi sembrano due satrapi d’Egitto. Simone – Guarda che gravità. Pistacchio – Attento, e zitto. 6 Pistacchio – Uncle, uncle! Quick, go and see where Don Simone is, where he’s hiding. (Fretting.) Simone – What’s all this shouting, are you crazy? Pistacchio – They’re here, they have arrived. Simone – Who has arrived? Pistacchio – The Doctors, good heavens, the lawyers. Simone – Ah, good. And where are they? Pistacchio – They are coming up the stairs. Simone – Let’s go meet them. Pistacchio – They’re already here. Simone – What a majestic aspect! Pistacchio – They look like two satraps from Egypt. Simone – What gravity. Pistacchio – Careful, be quiet. Scena IV Don Martino e Donna Lisetta vestiti d’avvocati, e detti. Scene IV Don Martino and Donna Lisetta wearing lawyers’ gowns, and the above. 52 7 Martino – Qui è Baldo, e Bartolo, è qui Solone. Lisetta – Qui v’è Demostene, v’è Cicerone. Martino – Salvete Domini. Lisetta – Valete amici. Martino/ Lisetta – Siam qui a difendere la verità. Ma già che trattasi di matrimonio, Cornelio Tacito deciderà. 8 Pistacchio – Signoris benvenutis. Simone – Fate gratias cum nobis sedebare. Martino – Sede, amice. (A Lisetta e siede.) Lisetta – Sedebo. (Siede.) Simone/ Lisetta – Assediare. (Siedono.) Martino – In somma, miei signori, cosa saper bramate dalle nostre gran teste letterate? Pistacchio – Or io v’informerò. Eccellentissimi, dottori sapientissimi, sappiano, che il mio caso è degno di pietà. Io mi ritrovo confuso tra due mogli; e se per sorte son costretto a pigliar la moglie incerta, ho timor d’aver anche incerti i figli; onde datemi voi lumi e consigli. Martino – Trattandosi di femmine il caso è filosofico. Lisetta – Trattandosi di femmine, il caso è metafisico. Pistacchio – Ehi là, fermate, voi solo baruffate, voi niente concludete, ma io di legge insegno a quanti siete. 7 Martino – Here come Baldo and Bartolo, here comes Solon. Lisetta – Here comes Demosthenes, here comes Cicero. Martino – Salvete Domini. Lisetta – Valete amici. Martino/ Lisetta – We are here to uphold the truth. But since it’s a case of matrimony Cornelius Tacitus will rule. 8 Pistacchio – Signoris benvenutis. Simone – Fate gratias cum nobis sedebare. Martino – Sede, amice. (To Lisetta, sitting down.) Lisetta – Sedebo. (She sits down.) Simone/ Lisetta – Assediare. (They sit down.) Martino – So, gentlemen, what do you wish to learn from our scholarly minds? Pistacchio – Let me inform you. Most excellent, most learned Doctors, know that my case is pitiful. I find myself doubtful between two brides; and if by chance I’m forced to take the wrong wife, I fear I will have also the wrong children; therefore I need your enlightenment and advice. Martino – Since we’re dealing with women the case is philosophical. Lisetta – Since we’re dealing with women the case is metaphysical. Pistacchio – Hey there, stop it, all you seem to do is squabble, you’re coming to no conclusion, but I’ll teach you all about law. 53 9 Facciamo un po’ silenzio signori sapientissimi, e meco se avet’animo venite a disputar. Fœmina non est fœmina? Hominum non est masculum? Per questo il punto è fisico, fisico vuol dir medico, medico è nome critico chi critica fa piangere chi piange non può ridere: così concludo, e termino, che in oggidì le femmine son fisiche, son critiche, son tutte tutte lagrime, e misero è quel masculum che ci ha da contrattar. 9 Be quiet for a moment, you know-it-all, and see if you dare argue with me. Fœmina non est fœmina? Hominum non est masculum? That’s why the question is physical, physical means medical, medical is a critical notion, critics makes you cry, he who cries cannot laugh: so I conclude, and I end, that nowadays women are physical, are critical, they all make you cry and wretched is that masculum who has to deal with them. Scena V Don Simone, indi Baronessa. Scene V Don Simone, and the Baroness. 10 Simone – Adesso che mi sono consigliato ne so meno di prima. Madama, servo vostro. Baronessa – E avete ardire di salutarmi ancor! In questo punto a Napoli tornar voglio di fretta, per far contro di voi giusta vendetta. Simone – Ma cosa c’entro io! Orsù, signora, parliamo un po’ sul sodo: se voi siete poco contenta del nipote mio, pur che vogliate voi, vi sposo io. Baronessa – Dite da vero? Simone – Parlo con schiettezza. Baronessa – Ed io per vendicarmi col Barone l’offerta accetto di Don Simone. Simone – Oh che gusto. Ma zitta. 10 Simone – Now that I got counselled I know less than before. Your servant, Madam. Baroness – And you dare still greet me! At this point I wish to return to Naples immediately, where I’ll plan my rightful vengeance against you. Simone – What fault is it of mine? Please, madam, let’s be sensible: if you are dissatisfied with my nephew, I will marry you if you accept. Baroness – Really? Simone – Truly. Baroness – To spite the Baron, I accept the proposal of Don Simone. Simone – Oh, how pleased I am. But hush. 54 Baronessa – No, non parlo. Simone – Adesso alla sordina voglio andare le feste per le nozze ad ordinare. 11 Vezzosa cara sposa voi rimbambir mi fate; il cor mi consolate lo sento a saltellar. Ballando d’allegrezza già fo la furlanetta; per voi, o mia diletta, gran festa voglio far. (Parte.) Baroness – Don’t worry, I won’t say a word. Simone – I’m going secretly to organise our wedding feast. 11 My charming bride you make me lose my mind; you comfort my heart, I can feel it leap. Let me twirl with joy, and dance a furlana; for you, my beloved, I wish to arrange a great feast. (He leaves.) Scena VI Baronessa, indi Don Martino. Scene VI The Baroness, then Don Martino. 12 Baronessa – Così, così si faccia. In questa guisa contro quell’alma ardita la mia vendetta più farò compita. Martino – Ed è vero, o madama, che a casa volete ritornare? Baronessa – Lo dissi; ma per or convien restare. Martino – Abbiamo novità? Baronessa – Sì, mio padrone. Martino – Ed è? Baronessa – Che sposerò con Don Simone. Martino – (Oh poveretto me!) Ma Baronessa, della vostra promessa questi i patti non son. Di voi stupisco non si tratta così, vi riverisco. (In atto di partire.) Baronessa – Fermatevi. Martino – Non voglio. Baronessa – M’ascoltate. Martino – Ma se... Baronessa – Via, per favor. Martino – Son qua, parlate. Baronessa – Ditemi Don Martino, è noto a voi 12 Baroness – So be it. This way that impudent man will taste my revenge. Martino – Is it true, Madam, that you wish to return home? Baroness – I did say it; but for now I should stay. Martino – Are there any news? Baroness – Yes, sir. Martino – And what are they? Baroness – That I’ll marry Don Simone. Martino – (Oh, wretched me!) But Baroness, your promise, that’s not what we agreed. I’m astonished, that’s no way to behave, good–bye. (Leaving.) Baroness – Wait. Martino – I will not. Baroness – Hear me. Martino – But if... Baroness – Please, I beg you. Martino – All right, speak. Baroness – Tell me Don Martino, do you know 55 il mio temperamento? Martino – So, che siete una Dama bizzarra; che vi piace con tutti conversar; che vi diletta il festino, il passeggio, l’allegria, ma nemica però di gelosia. Baronessa – Qui vi volevo appunto; ed io per questo ho piacer d’appigliarmi, caro mio Don Martino, compito, e bello, a un uomo un po’ attempato, e scioccarello. Martino – Ma che! Son io geloso? Baronessa – Siete giovine, e basta. Martino – No, Madama, non son di questa pasta. Baronessa – Dunque alla prova. Martino – Oh brava. Baronessa – Figuriamoci. Ch’io sia già vostra moglie: si fa notte; a voi vien volontà di andare in letto, a me desio d’andare ad un festino. Martino – Andate pur, che dorme Don Martino. Baronessa – Dunque si dorme? Martino – Dormo. Baronessa – Ecco alla porta già picchia un cavaliere: corro ad aprirla: subito il cicisbeo mi dà di braccio, ed io a lui favello in queste forme. Martino – Parlate pur, che Don Martino dorme. 13 Baronessa – Or che dorme il mio sposino mio compito Cavaliere, zitti zitti, pian pianino, al festin vogliamo andar. Martino – Adorata mia speranza andiam pur, che ci ho diletto; Don Martino già sta in letto far possiam quel che ci par. Baronessa/ Martino – Già la moglie ed il marito il lor debito san far. my temperament? Martino – I know that you are an exuberant lady; that you like talking with people; that you enjoy feasts, a good stroll, merry–making, but you don’t like jealousy. Baroness – Now that’s precisely what I mean; that’s why I wish to marry, my dear Don Martino, my courteous and handsome man, someone who is a little older and somewhat dumb. Martino – What! Do you think that am I jealous? Baroness – You’re young, I need say no more. Martino – But, Madam, I’m not like that. Baroness – To the test, then. Martino – Oh, good. Baroness – Let’s pretend I am already your wife: it’s evening; and you want to go to sleep, while I wish to go to a feast. Martino – You may go, for Don Martino is asleep. Baroness – Therefore we are asleep? Martino – I am asleep. Baroness – Someone knocks on the door, it’s a gentleman: I run to open: right away the gallant man offers me his arm and this is what I tell him. Martino – Go ahead, speak, for Don Martino is asleep. 13 Baroness – Since my husband is asleep, courteous gentleman, we can slip out quietly and go to the feast. Martino – My beloved, let’s go, with pleasure; Don Martino is in bed, so we can do as we please. Baroness/ Martino –The husband and wife are already running into trouble. 56 Baronessa – Sono entrata nel festino ballo già con questo, e quello, Martino – Balla balla che Martino sta tranquillo a riposar. Ma se a caso lui si desta e nel letto non vi trova, viene anch’esso nella festa, e comincia a taroccar. Baronessa – Se Martin mi farà questo lo saprò così domar. Martino – Date, date , date forte non son io il primo questo che si fa dalla consorte con pazienza schiaffeggiar. Baronessa – No, caro Martino son Dama prudente, modesta, e paziente, con voi mi starò. Martino – Di me più buonino più sposo giocondo, no, no, che nel mondo trovar non si può. Quel labbro sincero se il vero mi dice, contento e felice per sempre starò. (Partono.) Baroness – I am at the feast, dancing with everyone. Martino – Dance, dance, so long as Martino is peacefully asleep. But if by chance he wakes up and doesn’t find you in bed, he’ll join you at the feast and give you a piece of his mind. Baroness – If Martino does that to me I will tame him thus. Martino – Hit, hit hard, I’m not the first husband who tolerates a slap from his wife. Baroness – Well then, dear Martino I am a sensible lady, modest and patient, I will remain with you. Martino – A more good–hearted more cheerful husband than I cannot be found in the entire world. If your lips are sincere and have told me the truth I’ll be happy and delighted forever more. (They leave.) Scena VII Gabinetto. Don Martino, e Folletto. Scene VII A study. Don Martino, and Folletto. 14 Martino – (Eccoli, sono qua. Il mio pensiero credo, che avrai capito.) Folletto – (Di quanto m’ordinò, sarà servito.) 14 Martino – (Here they are. My plan I trust, is clear to you.) Folletto – (I’ll do as you told me.) 57 Scena VIII Don Pistacchio, Donna Lisetta, e Don Martino. Scene VIII Don Pistacchio, Donna Lisetta, and Don Martino. Martino – Don Pistacchio. Pistacchio – Chi è? Martino – Sentite a me: la Baronessa vuole portarsi al vicin Tempio della Cumana celebre Sibilla... Lisetta – Per l’oracolo forse consultare? Martino – Sì, signora. Pistacchio – E cosa abbiam da fare? Martino – Di venire nel tempio ancora voi per sciogliere cotanta differenza, e sentir dell’oracol la sentenza. Lisetta – (Tutto ho capito già.) Pistacchio – Voi che ne dite? Lisetta – Andiam, per me son pronta. Pistacchio – E se per sorte, la Sibilla vi dice di lasciarmi? Lisetta – Darsi pace convien, dolce mia vita; vi sposerete l’altra, ed è finita. Pistacchio – Ah cagna! E avresti core d’abbandonarmi? Mi sento... ahimé... da pianger mi viene. Lisetta – Or comprendo, cuor mio, che mi vuoi bene. 15 Ah no, non pianger più! Quei mesti occhietti ravviva per pietà. Sappi mio nume, ch’io fida t’amerò, che questo cuore tutto per te sarà. Vadasi pure l’oracolo a sentir. Della Sibilla non pavento il voler. Fin negli Elisi fedel ti seguirò ferma, e costante, o sposa, o amica, o sventurata amante. 16 Dolce fiamma del mio core, t’amerò, sarò costante; e saprà quest’alma amante delle stelle trionfar. Martino – Don Pistacchio. Pistacchio – Who is it? Martino – Listen to me: the Baroness intends to go to the nearby temple of the famous Cumaean Sibyl... Lisetta – To consult the oracle? Martino – Yes, madam. Pistacchio – And what are we to do? Martino – You must go to the temple too to smooth out all the difficulties and hear the oracle’s verdict. Lisetta – (I have understood everything.) Pistacchio – What do you say? Lisetta – Let’s go, I’m ready. Pistacchio – And if by chance the Sibyl says you must leave me? Lisetta – Then we must resign, my beloved; you’ll marry the other one, and that’s that. Pistacchio – Ah, bitch! And you would leave me? I feel... poor me... I feel like crying. Lisetta – Now I know, my beloved, that you love me. 15 Ah, no, stop crying! Your sad eyes must brighten up. Rest assured, my idol, that I’ll love you truly, that this heart will be yours. Let us go and hear the oracle. I do not fear the Sibyl’s will. Even to heaven I will follow you, constant and firm, as wife, friend or hapless lover. 16 Sweet flame of my heart, I shall love you and be faithful, and my love will overcome the stars. 58 Mia speranza in te riposa; ti consola, amato bene; quelle luci più serene fa ch’io veda scintillar. Alme belle innamorate, che pietose, e care siete, ah da me da me apprendete un amante a consolar. (Parte.) 17 Martino – (Lisetta m’ha capito.) Pistacchio – Ah Don Martino. Di costanza colei è un vero esempio. Martino – Or meglio lo sapremo. Al tempio. Pistacchio – Al tempio. (Partono.) I place all my hope in you; take comfort, my beloved; let your eyes brighten up and sparkle for me. People in love, who are compassionate and good–natured, learn from me how to comfort a lover. (She leaves.) 17 Martino – (Lisetta has understood.) Pistacchio – Ah, Don Martino. She is a true paragon of faithfulness. Martino – Now we shall see. To the temple. Pistacchio – To the temple. (They leave.) Scena IX Ameno boschetto tutto folto di cipressi, e mirti; in mezzo tempio della Sibilla Cumana, con simulacro fatto a guisa di sole, dove si leggono alcune cifre artefatte. Folletto, indi Baronessa; poi Donna Lisetta, dopo Don Martino, e Don Pistacchio. Scene IX A pleasant grove of cypress and myrtle, in the middle of which stands the temple of the Cumaean Sybil; a simulacrum in the shape of the sun, inscribed with faked writing. Folletto, then the Baroness; then Donna Lisetta, then Don Martino, and Don Pistacchio. Folletto – A forza di denaro il custode del tempio ho già sedotto acciò mi lasci far questa finzione. Le spose col Barone poco tardar potranno ad arrivare; dunque all’erta Folletto... Ma sento gente... al posto ora mi metto. (Si cela dietro al simulacro.) 18 A 4 – Askara ki kara kiriki ko kola, ka kara ka kala, kula kulà. Lisetta/ Martino – Oh sapientissima Sibilla amabile Fra queste tenebre lume voi dateci, Folletto – With a little money I bribed the temple’s custodian so that he’ll let me carry out this sham. The brides and the Baron will be here soon; so watch out, Folletto... People are coming... to my place. (He hides behind the simulacrum.) 18 A 4 – Askara ki kara kiriki ko kola, ka kara ka kala, kula kulà. Lisetta/ Martino – Oh wise, gracious Sybil, we walk in darkness, give us light, 59 fateci intendere la verità. A 4 – Askara ki kara kiriki ko kola, ka kara ka kala, kula kulà. Pistacchio/ Baronessa – Col vostro lucido saper vastissimo, tante discordie fate sospendere, deh consolateci per carità A 4 – Askara ki kara kiriki ko kola, ka kara ka kala, kula kulà. Folletto – (parlando per di dietro il simulacro) Le spose saran spose: il vero sposo più sposo non sarà: così del fato vuol la volontà. Pistacchio – Che voce d’orco è questa! A 3 – Che cifre portentose! Pistacchio – Le spose saran spose. A 3 – Lo sposo signor no. Pistacchio – Insomma poverello zitello io morirò. A 3 – Così le stelle vogliono: al Ciel si sottometta. Pistacchio – Sibilla maledetta, oracolo briccone. A 3 – Rispetto al Ciel Barone Pistacchio – Son tutte falsità. Folletto – Di Giove adesso un fulmine punire ti saprà. (Dall’alto del tempio scoppia un fulmine artefatto) A 4 – Oh che segno spaventoso! Fuggo, scappo, mi nascondo. make us know the truth. A 4 – Askara ki kara kiriki ko kola, ka kara ka kala, kula kulà. Pistacchio/ Baroness – With your clear and vast knowledge put an end to all our disagreements, ah, give us comfort for pity’s sake. A 4 – Askara ki kara kiriki ko kola, ka kara ka kala, kula kulà. Folletto – (speaking from behind the simulacrum) The brides shall be brides: the intended groom shall not be a groom any more: this is fate’s will. Pistacchio – What a horrible voice! A 3 – What a prodigious oracle! Pistacchio –The brides shall be brides. A 3 – But not the groom, no sir. Pistacchio – That is to say, wretched me, that I must remain a bachelor. A 3 – That’s what the stars want: submit to Heaven’s will. Pistacchio – Cursed Sybil, damn oracle. A 3 – Don’t offend Heaven, Baron Pistacchio – These are nothing but lies. Folletto – Jupiter’s lightning shall punish you immediately. (A fake lightning flashes from the top of the temple) A 4 – Oh, what a frightening sign! Let me flee, run, hide myself. 60 Ah per me/te non v’è più mondo, Giove mio pietà, pietà. (Partono.) 19 Folletto – La scena veramente è stata bella; ma presto a casa voglio ritornare, perché mi starà Betta ad aspettare. (Parte.) Ah, there is no escape, Jupiter, have mercy. (They leave.) 19 Folletto – What a delightful scene; and now I’ll rush home, where Betta is waiting for me. (He leaves.) Scena X Baronessa, e Don Martino di nuovo, indi Don Simone. Scene X The Baroness, and Don Martino again, then Don Simone. Baronessa – Dunque per il Barone fu fatta questa burla? Martino – Per appunto; anzi ch’io mancherei al dovere di sposo, e Capitano, s’or non vi palesassi un altro arcano. Baronessa – Parlate pur. Martino – Sappiate, che di quanto è accaduto in questo giorno, io son stato l’autor. Baronessa – Dunque colei... Martino – Colei, sposina bella, è dama al par di voi, è mia sorella. Baronessa – Tanto inganno perché? Martino – Perché mi vidi da voi per questo sciocco rifiutato; eccovi già l’arcan tutto svelato. Ah madama. Appieno i pregi miei no, non saprete; ma se qui gli dirò voi stupirete. 20 Quando il labbro io movo a riso, quando dolce vibro un sguardo, come amor, che scocca un dardo, son furbetto, anch’io piagar. Son falcone, son sparviero, Baroness – Then it was for the Baron that the sham was organised? Martino – Precisely; and I would fail my duty of husband and Captain if I didn’t reveal to you another secret. Baronessa – Tell me. Martino – Know then that of all that has happened today I was the author. Baronessa – Then she... Martino – She, my fair bride, is as much a lady as you are, she is my sister. Baronessa – Why so many deceits? Martino – Because I found myself rejected in favour of that simpleton; now you know all the truth. Ah, my lady, you don’t know half of my qualities; if I were to tell you you’d be astonished. 20 When my lips curve up into a smile, when I cast a sweet glance, I am like Cupid, shooting darts, I niftily find my mark. I am a falcon, a hawk, 61 d’ogni donna io fo’ rapina : con un vezzo, un’occhiatina, le so tutte conquistar. (Parte.) every woman falls prey to me: with a caress and a wink, I conquer them all. (He leaves.) Scena XI Baronessa, e Don Simone Scene XI The Baroness and Don Simone 21 Baronessa – Sento un’amena voce, che mi consola, e dice, spera, sarai felice, calma il tuo core avrà. D’amore è questa qui, lo sento, signor sì. Ah caro amor non più, che il cor mi va su e giù: sposino mio diletto, son lieta, e son contenta: per te già s’aumenta la mia felicità. 21 Baronessa – I hear a pleasant voice which comforts me and says have hope, you will be happy, your heart will find peace. It’s the voice of love, I know it, yes I do. Ah, sweet love, stop it, my heart is skipping beats: my dear, beloved groom, I’m full of joy, I’m delighted: because of you my happiness is complete. Scena XII Gabinetto. Bettina, e Folletto, indi Don Pistacchio. Scene XII A study. Bettina, and Folletto, then Don Pistacchio. 22 Bettina – Tutto questo è accaduto? Folletto – E questo è un niente; il meglio fra poco si vedrà. Bettina – Da vero, che il Baron mi fa pietà! Folletto – Eccolo, qua sen viene. Bettina – Osserva, osserva, spaventato il meschin mi pare ancora. Pistacchio – No, più moglie non prendo in mia malora. Le feste sospendete; (Parlando a due servitori.) Mandate via di casa i credenzieri, e i sguatteri con loro, e i cucinieri. (I servi partono.) 22 Bettina – Has all that actually happened? Folletto – That’s nothing; the best has still to come. Bettina – I really feel sorry for the Baron! Folletto – There he is, he’s coming this way. Bettina – Look, look, he still seems frightened. Pistacchio – No, no more marriage, to the devil with it. Stop making preparations; (To two servants.) Dismiss the stewards, and also the scullery boys, and the cooks. (The servants leave.) 62 Bettina – Signor, qual novità! Le vostre nozze ognun per festeggiar già è preparato. Pistacchio – Che nozze! Voglio andarmi a far soldato. Bettina – Come? Folletto – Perché? Don Pistacchio – Così vuol la Sibilla, l’oracolo, il malanno, la saetta, Giove, Saturno, il ciel, la mia disdetta. Bettina – Voi mi fate stupire. Don Pistacchio – Dimmi un poco... (Perbacco, che sarai per farla bella.) Lisetta – (Zitto, l’amico è qua.) Martino – (Sentiam, sorella.) Don Pistacchio – Per far restar bugiarda la Sibilla, avresti a caro tu d’esser mia sposa? Martino – (Digli di sì.) Bettina – E perché no? Sarebbe troppa la sorte mia. Don Pistacchio – E mia sposa sarai? Lisetta – Oh che pazzia! Don Pistacchio – Presto correte, andate; le genti licenziate, fermate a nome mio. Cena, festino, tutto fate allestire in un momento. Bettina – Vado con mio piacer. Folletto – Volo contento. (Partono.) Lisetta – (Or lascia fare a me.) Don Pistacchio, se prendere più moglie non volete, almen vi compiacete le nozze d’onorar di Don Simone. Don Pistacchio – Mio zio si sposa? Lisetta – Sì. Don Pistacchio – Resto in stivale! E la sposa qual’è? Lisetta – La mia rivale. Pistacchio – Tutto questo ci sta! Ed io a costo Bettina – Sir, what’s this! Everyone is ready to celebrate your wedding. Pistacchio – What wedding! No more wedding. Bettina – What? Folletto – Why? Don Pistacchio – That’s the will of the Sybil, the oracle, misfortune, thunderbolt, Jove, Saturn, the heavens, my ill luck. Bettina – You leave me dumbfounded. Don Pistacchio – Tell me... (By Jove, what an idea.) Lisetta – (Hush, here is our friend.) Martino – (Let’s hear, sister.) Don Pistacchio – To make a liar of the Sybil, would you marry me? Martino – (Say yes.) Bettina – Why not? It’s too good a chance for me. Don Pistacchio – So you will be my wife? Lisetta – Oh what madness! Don Pistacchio – Hurry, go; stop the people that I dismissed. Banquet, feast, have everything prepared. Bettina – Gladly I go. Folletto – Happily I fly. (They leave.) Lisetta – (Leave it to me now.) Don Pistacchio, if you no longer wish to marry, at least be kind enough to attend Don Simone’s marriage. Don Pistacchio – My uncle is getting married? Lisetta – Yes. Don Pistacchio – I’m thunderstruck! And which is the bride? Lisetta – My rival. Pistacchio – My goodness! Then even if 63 di restare da Giove incenerito, a lor dispetto vi farò marito. Martino – Ma voi siete un volubile, ora sì, ora no. Lisetta – Ah quanto, o caro, per te penar degg’io! Abbi di me pietà, bell’idol mio. 23 Prigioniera abbandonata pietà merto, e non rigore; Ah fai torto al tuo bel core se mi stai più a lusingar. (Piange.) Martino – Vil trofeo d’un’alma imbelle è quel ciglio allor che piange (a Lisetta). Qui non s’usa come al Gange le donzelle a corbellar (a Don Pistacchio). Pistacchio – Se più turbo il tuo riposo, se m’accendo ad altro lume, che mi faccia il cieco nume orbo affatto diventar. Lisetta – Dunque tu sarai mio sposo? Pistacchio – Da Barone sì, lo giuro. Martino – Io però non l’assicuro. Lisetta/ Pistacchio – Non ci stia più a frastornar. Martino – Basta, basta, lo vedremo. Lisetta/ Pistacchio – Sì Signor, sposar vogliamo. A 3 – Presto in sala dunque andiamo queste nozze a festeggiar. (Partono.) Jupiter might reduce me to ashes, in spite of them I will marry you. Martino – My, you are inconstant! One moment yes, the next no. Lisetta – Ah, how much, my beloved, must I suffer on your account! Have mercy on me, my idol. 23 Captive and abandoned, I deserve your pity, not your rigour; Ah, you wrong your own good heart if you keep flattering me. (She weeps.) Martino – You show a faint heart when you weep (to Lisetta). Here we are not accustomed to making fools of ladies (to Don Pistacchio). Pistacchio – If I ever cause any more distress to you, if I ever warm to anyone else’s fire, may the blind god bereave me. Lisetta – Then you will marry me? Pistacchio – I give you my baronial word. Martino – I wouldn’t be so sure about it. Lisetta/ Pistacchio – Stop pestering us. Martino – Well, well, we shall see. Lisetta/ Pistacchio – Yes, we want to get married. A 3 – Let’s hurry to the hall, then to celebrate the marriage. (They leave.) Scena XIV Gran sala illuminata, con tavola nel mezzo imbandita. Bettina, e Folletto, indi Baronessa, e Don Simone. Scene XIV A great hall, lit, with a table in the middle laid for a banquet. Bettina, and Folletto, then the Baroness, and Don Simone. 24 Bettina – Allegri staffieri. Folletto – Attenti servite. Bettina – La mensa imbandite. Folletto – Bottiglie portate. 24 Bettina – Smile, footmen. Folletto – Work diligently. Bettina – Lay the table. Folletto – Bring the bottles. 64 A 2 – Godete, brillate, che festa si fa. Baronessa – Che stanza superba! Simone – Che reggia d’amore! Baronessa – Rallegra il mio cuore. Simone – Consola abbastanza. A 2 – La cena, la danza qui spicco farà. A 2 – Delight, shine, we’re going to make merry. Baroness – What a magnificent hall! Simone – What a love palace! Baroness – It cheers my heart up. Simone – It’s quite comforting. A 2 – The banquet, the dancing will be wonderful. Scena Ultima Don Pistacchio, Don Martino, Donna Lisetta, e detti. Last Scene Don Pistacchio, Don Martino, Donna Lisetta, and the above. Martino – Che vago apparecchio! Lisetta – Che sala fastosa! Pistacchio – Che cena famosa! Martino – Che lauto banchetto! A 3 – Mi reca diletto, piacere mi dà. Baronessa/ Simone – Noi sposi fra poco saremo, sappiate. A 5 – Gran gusto ci date con tal novità. Lisetta/ Pistacchio – Fra poco, signori, noi pur sposeremo. A 5 – Più festa faremo, di più si godrà. Martino – A tavola dunque andiamo a cenare. Lisetta/ Pistacchio/ Baronessa/ Simone – No prima sposare vogliamo noi qua. Tutti – Amore, ed Imene, le faci accendete; qui presto scendete, che all’ordine è già. 25 Simone – (alla Baronessa) Cara sposa, vezzosa, bellina, Martino – What beautiful decorations! Lisetta – What a magnificent hall! Pistacchio – What a superbly laid table! Martino – What a scrumptious banquet! A 3 – It’s delightful, wonderful. Baroness/ Simone – Soon we’ll be husband and wife, you ought to know. A 5 – These news makes us very happy. Lisetta/ Pistacchio – Soon, ladies and gentlemen, we too will be married A 5 – That’s reason for additional joy. for more feasting. Martino – Let’s sit down at the table then, let’s go and have supper. Lisetta/ Pistacchio/ Baroness/ Simone – No, first we want to get married Tutti – Love and Hymen, light up your torches; hurry and descend on us for the time has come. 25 Simone – (to the Baroness) Dear bride, give your lovely, 65 la manina porgete su a me. Baronessa – Sì, son lesta, mio dolce sostegno; ecco il pegno d’amore e di fè. (Dà la mano a Don Martino.) Simone – Oh cospetto, qui resto di sasso! A 6 – Più bel spasso di questo non v’è. Pistacchio – (a Donna Lisetta) Ah mia vita, speranza gradita, ecco il punto d’unirmi con te. Lisetta – Sì, mio core, ne siete ben degno; ecco il pegno d’amore, e di fè. (Dà la mano a Don Simone.) Pistacchio – Oh cospetto, qui resto di sasso! A 6 – Più bel spasso di questo non v’è. Pistacchio – Ma digiuno non resta il Barone; un boccone già tengo da re: cara Betta, sposiamoci in fretta, Betta – Ecco il pegno d’amore, e di fè. (Dà la mano a Folletto.) Pistacchio – Oh che scena, oh che burla cospetto! a 6 – Più diletto di questo non v’è. Pistacchio – Orsù di casa mia sfrattate o donne infeste; sospendasi le feste... a 6 – Le feste s’han da far. Pistacchio – Smorzate le candele. a 6 – Più lumi preparate. Pistacchio – La mensa sparecchiate. a 6 – Portate da mangiar. Pistacchio – Io solo qua comando. a 6 – Comanda la Sibilla. Pistacchio – (sommesso) O nome venerando! a 6 – Dovete zitto star. Pistacchio – Che belle nozze ho fatto! a 6 – Pazienza aver vi tocca. Pistacchio – Con tre polpette in bocca charming hand to me. Baroness – Yes, right away, my sweet support; here is my pledge of love and faithfulness. (She gives her hand to Don Martino.) Simone – Goodness gracious, I’m dumbfounded! A 6 – How most amusing! Pistacchio – (to Donna Lisetta) Ah, my life, my hope, the time has come to get married. Lisetta – Yes, my heart, you are well worthy of it; here is my pledge of love and faithfulness. (She gives her hand to Don Simone.) Pistacchio – Goodness gracious, I’m dumbfounded! A 6 – How most amusing! Pistacchio – But this Baron won’t be left without a bride; I have a morsel worthy of a king: lovely Betta, let’s get married Bettina – Here is my pledge of love and faithfulness. (She gives her hand to Folletto.) Pistacchio – Oh, what a scene, what a mockery, my goodness! a 6 – How most amusing! Pistacchio – Well then, out of my house, leave, you pestering women; let’s stop the celebrations... a 6 – The celebrations must go ahead. Pistacchio – Put out the candles. a 6 – Light up more candles. Pistacchio – Clear the table. a 6 – Bring in the food. Pistacchio – I am the one who gives the orders here. a 6 – The Sybil is the one who gives the orders. Pistacchio – (under his breath) O venerable name! a 6 – You must be quiet. Pistacchio – I made a great match indeed! a 6 – You must be patient. Pistacchio – I tasted three dainty morsels 66 digiuno ho da restar. Tutti – Uno sposo di tre femmine, ma di nessuna sposo, ridicolo, e grazioso, chi vuol vedere è qua. Ai buoni posti, maschere, a prendere i biglietti, la spesa è due soldetti, contento ognun sarà. and have bee left to starve. Tutti – A groom with three brides but husband of none, ridiculous yet charming, come and see him, people. Go to your places, ushers, to sell the tickets, for only two farthings, you’ll all have a great time. 67 Orchestra Internazionale d’Italia Violini: Emillian Piedicuta**, Olivier Pastor*, Joseph Cardas, Sophie Chang, Robert Dan Trut, Ildiko Antalffy, Sandor Tekeres, Csilla Szoverdi, Antonella Piscitelli, Mircea Tataru*, Venetia Onofrei Rili, Oxana Apahidean, Vladimir Piedicuta, Silvana Pomarico, Adriana Stoica, Angie Tirelli Viole: Gabriel Bala*, Cristian Ifrim, Dana Bala, Michela Zanotti, Erzsebet Kiraly, Massimiliano Monopoli Violoncelli: Marin Cazacu*, Razvan Gabriel Suma, Sylva Jablonska, Olga Bianca Manescu Contrabbassi: Roberto Pomili*, Luigi Lamberti Flauti: Federica Bacchi*, Monica Crazzolara Oboi: Luca Stocco*, Diane Lacelle, Giuseppe Longo Clarinetti: Michele Naglieri* Corni: Ioan Gabriel Luca*, Sebastiano Panebianco ** concertmeister *prime parti 68