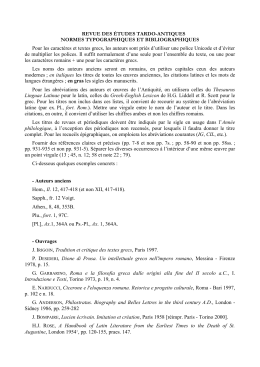

Zefiro Alfredo Bernardini −Harmonie & Turcherie Donizetti Haydn Mendelssohn Mozart Rossini Schubert Spohr Witt Tracklist ⁄ English ⁄ Français ⁄ Italiano 2 Menu −Harmonie & Turcherie Donizetti Haydn Mendelssohn Mozart Rossini Schubert Spohr Witt 01. Michael Haydn (1737-1806) Marcia Turchesca, in do maggiore, ST610/P.65 2 fl., 2 ob., 2 cl., 2 fag., cfag., 2 tr., 2 cor., 3 perc. — Salisburgo, 6 agosto 1795 A 391 4:25 02. Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) Die Sieben letzten Worte unseres Erlösers am Kreuze, Hob.XX/2 Introduzione alla seconda parte, in la minore fl., 2 ob., 2 cl., 2 fag., cfag., 2 cor., 2 trb. — Eisenstadt – Vienna, 1796 Largo e cantabile 03. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Die Entführung aus dem Serail, KV 384 Marsch der Janitscharen, in do maggiore 2 fl., 2 ob., 2 cl., 2 fag., cfag., 2 tr., 2 cor., 3 perc. — Vienna, 1782 4:33 1:53 04. Friedrich Witt (1770-1836) Concertino per oboe e fiati, in do maggiore ob. solo, 4 cl., 2 fag., cfag., tr., 2 cor., trb. — Wertheim, 1809? Solista: Paolo Grazzi Adagio – Polacca 7:29 05. Gioacchino Rossini (1792-1868) Il Turco in Italia Sinfonia, in re maggiore (arr. Giorgio Mandolesi) fl., 2 ob., 2 cl., 2 fag., 2 tr., 2 cor., trb., cimb., 3 perc. — Milano, 1814 Adagio – Allegro 8:37 06. Gaetano Donizetti (1797-1848) Sinfonia a soli strumenti di fiato, in sol minore fl., 2 ob., 2 cl., 2 fag., 2 cor. — Bologna, 19 aprile 1817 Andante – Allegro 4:53 3 Menu 07. Giuseppe Donizetti (1788-1856) Marcia di Mahmoud, in fa maggiore (arr. Alfredo Bernardini) fl., 2 ob., 2 cl., 2 fag., cfag., 2 tr., 2 cor., cimb., 3 perc. — Istanbul, 1829 2:46 08. Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809-1824) Nocturno, in do maggiore, MWV P.1 fl., 2 ob., 2 cl., 2 fag., tr., 2 cor., cimb. — Bad Doberan, 1824 Andante – Allegro vivace 9:42 09. Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Eine kleine Trauermusik, in mi bemolle minore, D.79 2 cl., 2 fag., cfag., 2 cor., 2 trb. — Vienna, 19 settembre 1813 Grave con espressione 5:19 Louis Spohr (1784-1859) Notturno Op. 34, in do maggiore 2 fl., 2 ob., 2 cl., 2 fag., cfag., 2 tr., corno di postiglione, 2 cor., trb., cimb, 3 perc. — Vienna?, 1815 10. Marcia moderato 11. Menuetto allegro e Trio 12. Andante con variazioni 13. Polacca e Trio 14. Adagio 15. Finale vivace Total time 2015 / ©2015 Outhere Music France. Recorded in the Gustav Mahler Hall, Kulturzentrum Grand Hotel, Dobbiaco, 23-26 January 2015. Sound engineer: Simon Lanz. Artistic direction: Nicolas Hero. Editing and mastering: Alban Moraud. Produced by Outhere / Zefiro. 3:19 4:41 8:43 3:23 4:52 4:14 78:59 4 Zefiro — Harmonie Alfredo Bernardini direzione Marcello Gatti flauto traverso a 6 chiavi www.ensemblezefiro.it Martin Wenner, Singen (D) 2009 (da Heinrich Grenser, Dresda ca. 1790) flauto ottavino Rod Cameron, Mendocino (California, US) 2006 (da originali diversi, ca. 1800) flauto terzino James Cowlan, Liverpool ca.1825 flauto quartino Rudolf Tutz, Innsbruck 2000 (da originali diversi, ca. 1800) Luigi Lupo flauto traverso a 6 chiavi Rudolf Tutz, Innsbruck 2012 (da Heinrich Grenser, Dresda ca. 1790) flauto ottavino Martin Wenner, Singen (D) 2011 Alfredo Bernardini oboe a 2 chiavi Paolo Grazzi oboe a 2 chiavi Lorenzo Coppola clarinetto in do a 6 chiavi Alberto Ponchio, Vicenza 2014 (da Heinrich Grenser, Dresda ca. 1800) Alfredo Bernardini, Roma 2008 (da Grundmann & Floth, Dresda ca. 1800) Agnès Guéroult, Parigi 1993 (da Staudinger, Dresda ca. 1790) clarinetto in sib a 12 chiavi Agnès Guéroult, Parigi 2000 (da Heinrich Grenser, Dresda ca. 1810) clarinetto in la a 6 chiavi Daniel Bangham, Cambridge 1991 (da Heinrich Grenser, Dresda ca. 1800) Danilo Zauli clarinetto in do a 5 chiavi Agnès Guéroult, Parigi 1996 (da Staudinger, Dresda ca. 1795) clarinetto in la a 5 chiavi Ceccolini-Coppola, Roma 1998 (da Heinrich Grenser, Dresda ca. 1800) clarinetto in si bemolle a 12 chiavi Agnès Guéroult, Parigi 2000 (da Heinrich Grenser, Dresda ca. 1810) Miriam Caldarini clarinetto in do a 5 chiavi Igor Armani clarinetto in sib a 5 chiavi [tr. 4] [tr. 4] Agnès Guéroult, Parigi 2009 (da Heinrich Grenser, Dresda ca. 1800) Agnès Guéroult, Parigi 2012 (da Theodor Lotz, Vienna ca. 1785) 5 Alberto Grazzi fagotto a 9 chiavi Giorgio Mandolesi fagotto a 7 chiavi Michele Fattori fagotto a 9 chiavi Maurizio Barigione controfagotto a 7 chiavi Simone Amelli tromba in do, re e la [tr. 1, 3, 5, 7, 9] [tr. 4, 6, 8, 9] Peter de Koningh, Hall (NL) 1990 (da Heinrich Grenser, Dresda ca. 1806) Olivier Cottet, Boutigny-Prouais 2014 (da Heinrich Grenser, Dresda ante 1806) Peter de Koningh, Hall (NL) 1997 (da Heinrich Grenser, Dresda ca. 1806) Augustin Rorarius, Vienna ca.1800 Cristian Bosc, Chambave 2009 (da Johann Leonhard Ehe, Norimberga prima metà XVIII sec.) tromba in fa Mattew Parker, Carmarthenshire [UK] 2011 (da Johann Leonhard Ehe II, Norimberga inizio XVIII sec.) Francesco Gibellini tromba in do, re e la Cristian Bosc, Chambave 2010 (da Johann Leonhard Ehe II, Norimberga ca. 1750) tromba in fa Antiqui Instromenti, Sassuolo 2011 Dileno Baldin corno Francesco Meucci corno Corrado Colliard trombone alto Riccardo Armari cimbasso Pietro Piana, Milano ca.1820 corno di postiglione Pietro Callegari / Cristian Bosc trombone tenore Courtois Neveu Ainé, Parigi ca.1830 Charles Kretzschmann, Strasburgo ca.1830 Ewald Meinl, Geretsried (D) 2002 (da Johann Simon Schmied, Pfaffendorf 1789) Ewald Meinl, Geretsried (D) 2002 (da Johann Georg Eschenbach, Markneukirchen 1796) Riccardo Balbinutti, Stefano Bardella, Luca Favaro, Philipp Höller tamburo tedesco anonimo lombardo, ca.1900 tamburo militare Amat, Torino 2011 tamburo turchese Le soprano, Bergamo 2000 cappel cinese anonimo turco, 1995 triangolo anonimo Italia, seconda metà XIX sec. piatti turchi anonimo Asia minore, fine XX sec. piatti Sabian Banda Turca, Canada 2012 6 Menu HARMONIE & TURCHERIE From their first appearance in the Middle Ages, groups and bands of wind players played an important role in both civilian and military society, giving performances at various kinds of open-air celebrations. This was the principal function of the medieval Alta cappella. and subsequently of the Pifferi of Venice, the French Hautbois and the Stadtpfeifer, town pipers of the German-speaking countries who would later come to be known as Hautboisten. These groups of rigorously selected professionals were highly respected in their own communities. In the course of the Eighteenth Century, probably following the invention and rapid spread throughout Europe of a new version of the hautbois –with a more versatile dynamic range, greater chromatic capability and an extended compass, wind ensembles started to perform within buildings and their repertory widened to include music in churches, theatres and the home while they continued to be used on military and civilian occasions. The crucial moment of this development came in Vienna in 1782, when the Austrian Emperor Joseph II founded the Königliche Kaiserliche Harmonie (The Royal Imperial Harmonie) comprising 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 horns and 2 bassoons. The main function of the Harmonie was to provide music at the palace, performing the famous operatic arias that their patron had recently heard in the opera house, often to impress his guests or accompany a banquet. Because the novelty of the music was important, it had to be hurriedly arranged each time by the performers themselves. Having a first-rate Harmonie in one’s service now became an essential status symbol for the whole Austrian aristocracy and even beyond the bounds of the empire, so it was inevitable that the ablest and/or most famous composers of the time should soon be showing a keen interest in the development, writing for the ensembles in various genres such as military marches or music in a military style, funeral processions or serenades and even providing church music that dispensed with voices in favour of purely instrumental music rather than merely setting texts. Although the Ottoman Empire was regarded as a threat to the West – the siege of Vienna in 1683 being the culminating moment of military confrontation between the two societies – interest in all forms of oriental art including painting, sculpture, architecture, literature and music, not forgetting the culinary art, had been present in Europe since the Fifteenth Century. The improvement in diplomatic relations or even the establishing of new ones between East and West at the beginning of the Eighteenth Century created a climate favourable to commerce between the two which in turn provided the decisive impulse for the diffusion of one of the most intense and productive fashions of the century, that for all things Turkish. We find merchants importing carpets, embroidered cloths and oriental jewellery, people drinking Turkish coffee and consuming spicy food. Exotic literature such as ‘The Thousand and One Nights’ Entertainment’ inspired European artists who used the stories each in his own way. In theatrical 7 English works, including operas, tales about oriental characters and battles entered the collective imagination, as was the case with several eighteenth-century operas based on the confrontation between Bajazet and Tamerlane. By the end of the century many European composers were not only introducing Turkish or exotic elements into their operas but also using oriental references in their instrumental works. In fact, only a few elements of oriental music were adopted since the concepts of harmony and pitch in eastern music were too strange for western ears. The element most representative of Turkish music for western composers was the instruments it used, particularly in the mehter, the bands of the fearsome Janissaries, for whom they had the function of inspiring the fighting spirit. These were large bands of powerful wind instruments and various types of percussion. Among the most typical instruments was the z rn , a wooden double reeded conical folk oboe still much used today in traditional Turkish music, the davul, a large double-headed drum played with mallets and the Turkish crescent or Chinese pavilion, an ornamental standard hung about with bells and jingles also known as “jingling johnny”. European classical composers inserted these or their roughly equivalent western instruments into their scores creating loud, rhythmic music intended to suggest the exotic, sometimes with a hint of irony. Michael Haydn’s Turkish March is perhaps the work that best exemplifies the convergence between Harmonie and “Turkerie”. He takes the typical Harmonie components of 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 horns and 2 bassoons and adds 2 flutes, 2 trumpets, jingles and a Turkish drum. For our recording we had no qualms about adding a Turkish crescent as described above, an instrument frequently included in the percussion department even when not called for in the score. Harmonically, the only evocation of the Orient appears to be the modulation C-G-e-G, but the piece is strongly rhythmical and apart from short, soft interjections of melody there are few dynamic contrasts. Although also written for a large group of wind instruments, Joseph Haydn’s Introduction to Part Two of his oratorio The Seven Last Words of Our Saviour on the Cross could not be more different from his elder brother’s Turkish March. The oratorio for soloists, chorus and orchestra is the third version of the piece (the others are scored for orchestra and string quartet) and it is only here that Haydn inserts an introduction for wind instruments only, probably seeking an instrumental colour that would provide a contrast to that of the chorus and orchestra. The number that precedes the Introduction to Part Two is a setting of the words, “Elì, Elì, lamà sabactàni?“ – “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” – and closes with, “… nought shall separate us from thee in all eternity”. The reflection upon eternity inspires a series of sustained chords and a simple melody in a minor key on two trombones, wind instruments superbly fitted for church music. To these Haydn adds the typical Harmonie instruments plus a flute and a contrabassoon pitched an octave lower than the regular bassoon that had quickly become a feature of Viennese scores at the end of the Eighteenth Century. 8 The March of the Janissaries by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was recently (1980) rediscovered in a handwritten copy of Die Entführung aus dem Serail at the Staatsbibliothek Preussischer Kulturbesitz in Berlin. In the opera, in itself a fine indication of the popularity at the time of all things Turkish, the march precedes the chorus “Singt dem grossen Bassa Lieder” (Act I, No.5, opening of Scene No.6). In the libretto of the first performance in Vienna on the 16th July 1782 we find the following stage direction: Der Bassa Selim und Konstanze kommen in einem Lustschiffe angefahren, vor welchem ein anderes Schiff mit Janitscharenmusik voraus landet. Die Janitscharen stellen sich am Ufer in Ordnung, stimmen folgenden Chor an und entfernen sich dann. [“Bassa Selim and Constanze arrive in a pleasure craft preceded by another carrying the Janissary band. As soon as they have disembarked the Janissaries line up and sing the following chorus before they leave.”] Because Mozart frequently left writing his marches to the last moment, as was the case with the march of the priests in Die Zauberflöte, it is hardly surprising if they are not always included with the scores of the opera. Friedrich Witt’s Concertino was for a long time attributed to Carl Maria von Weber; recently, however, Witt’s authorship has been re-instated thanks to the scholar Nessa Glen. Witt worked assiduously at the court of Prince Löwenstein-Freudenberg-Wertheim near Würzburg where many of his compositions remained in the family library until recently. Among them are many Parthien, Harmonien and the oboe concertino here recorded, all showing the influence of his teacher Anton Roesler (aka Antonio Rosetti). While oboe concertos with orchestral accompaniment (strings and later also winds) remained very popular until the end of the Eighteenth Century, this work has the rare distinction of being accompanied by a Harmonie reinforced by a flute, a second pair of clarinets, trumpet, trombone and contrabassoon, many of which dialogue repeatedly with the solo oboe. The structure, in only two linked movements, with an adagio introduction followed by a Polacca in rondo form, is found later in many Nineteenth Century solo works. Gioacchino Rossini, like Mozart in his Entführung aus dem Serail, fell under the exotic spell of all things Turkish, writing two comic operas imbued with orientalism: L’Italiana in Algeri and Il Turco in Italia. The latter was premiered at La Scala Milan on 14 August 1814. Its initial reception was cool, but further performances that followed very swiftly in Rome, Venice, Leghorn, Paris, Lisbon and London were greeted with ever greater success assuring its position in the operatic repertoire for all time. The music of the Turco had actually nothing Turkish about it apart from the inclusion of a large percussion section and the use of various bright-sounding woodwinds. It would appear that each one of the latter is intended to relate to a particular character in the opera; for example, the mournful horn in the Adagio, the lively woodwinds in the Allegro, the trumpet fanfare. Our bassoonist Giorgio Mandolesi has made an arrangement of the Overture for Harmonie expanded to include flute, trumpet, trombone, contrabassoon, cimbasso and Turkish percussion, drawing inspiration from historical models such as those of 9 English Wenzel Sedlak (1776-1851), clarinettist with a Viennese Harmonie and prolific arranger. Gaetano Donizetti was not yet 20 when he wrote his Sinfonia for Winds. Like other youthful compositions showcasing wind instruments, this work was written primarily to deepen his knowledge of these instruments in order to use them to better effect in his operas. The present recording is a rarity among works written for Harmonie, being in a minor key (another is Mozart’s Serenade in C minor KV388) whereas most compositions for wind instruments are in a lighter, more entertaining vein. However, like Mozart, Donizetti held back from ending the piece in the minor mode and provides a happy ending, which he probably felt was required to accommodate public taste. The form, in two movements, a short Andante followed by an Allegro, is not dissimilar to the overtures to the operas which would soon make Donizetti one of the most celebrated composers of all time. Although almost unknown at the present day, Giuseppe Donizetti, Gaetano’s elder brother, enjoyed a reputation during his very comfortable life that was second to none. But not in Europe: in Turkey. In 1808 he was appointed Instructor General of the Imperial Ottoman Music at the court of Sultan Mahmud II (18081839) where, as well as writing The March of Mahmud (included on this disc) which became and remained for many years the national anthem of the Ottoman Empire, he trained and westernised Mahmud’s military bands, taught music to members of the Ottoman royal family, organised seasons of Italian opera and played host to a number of eminent European virtuosi, including Franz Liszt, when they visited Istanbul. Honoured with the title of Pasha, his affection for Turkey was such that he remained there until his death in 1856. There are several composers whose precociousness surprises, especially when their youthful compositions show particular ability and maturity. Such is the case with Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy who, at the age of 15 while on a summer holiday at the spa town of Bad Doberan on the Baltic coast near Rostock, came in contact with the local Harmonie and decided to dedicate his Nocturno to the ensemble. The maturity of the musician, scarcely more than a child, amazes the listener on hearing the harmonies of the elaborate introductory Andante. The opening 48 bars, in which a sinuous legato theme alternates between clarinet and horn, are followed by a darkly mysterious movement in which bassoons and cimbasso are interrupted by heroic trumpet calls before giving way to a lively Allegro with fanfare rhythms where the clarinet is given a prominence not unlike that of a first violin. In a letter to his sister Mendelssohn describes the instrument that he calls “Corno I. di Basso” on the score, even providing a sketch to show what it looked like. It seems to be a cimbasso, an instrument with the mouthpiece of a trombone but the body, in wood, of a bassoon, though with a shorter and wider bore. The instrument became widely used in Italy throughout the Nineteenth Century before being superseded by the ophecleide. The timbre of the cimbasso is unique, not being directly comparable with that of the trombone or bassoon or contrabassoon; rediscovering one was a pleasant surprise which we owe to the perseverence of Corrado Colliard 10 Menu who played it and to Guido Bizzi who lent us his own original instrument. In 1838 Mendelssohn decided to expand the orchestration for the Nocturno, adding several wind instruments, more percussion and renaming the work Ouverture für Harmoniemusik op.24. Far from abandoning the original version, however, he asked Simrock’s to publish it the very same year. The difference between the two versions makes for an interesting comparison between band and Harmonie music. Schubert’s Eine kleine Trauer Musik, which he subtitled Franz Schuberts Begräbnis Feyer, [March for Franz Schubert’s Funeral], was also the work of a very young man: he was 16. There are several reasons why it strikes us as unusual. The first is the extremely rare tonality of E flat minor; then there is the scoring. Schubert has two horns play the entire march alone to begin with, obliging them to deal with notes and intervals not easily accessible to the natural, i.e. valveless instruments of the time. The march is then repeated with the addition of two clarinets, two bassoons and a contrabassoon. There are various theories about the origin of this composition. A few months earlier (in May 1812), Schubert, only just fifteen, had had to cope with the death of his mother. He reacted by throwing himself heart and soul into composition, neglecting his studies of Latin and Mathematics at the prestigious Stadtkonvict, (Imperial Seminary) where he had been a boarder since 1808, and being severely rebuked by his tutors. Writing his own funeral march could have been his response to the college’s lack of compassion, a theory given weight by the fact that he returned to his father’s house a few months after writing this tragic piece, in November 1813. Louis Spohr’s Notturno op.34, in 6 movements, combines the musical characteristics of the Harmonie and the Turkish element more than all the other works on this recording. The subtitle is clear: “für Harmonie und Janitscharen-Musik” (for Harmonie and Janissary band) While the instruments and general character of some movements – such as the opening March, the Polacca and the lively Finale – are typically “Turkish”, in the others (the Minuetto, Andante and Adagio) the percussion is silent and the effect is of refined chamber music in which the instruments continuously exchange solos full of expressive virtuoso writing, with the clarinet again to the fore. In the Trio of the Polacca there is a curious passage in which a post-horn plays a call of just four notes accompanied only by the brass, something that must certainly have been familiar to listeners at the time. It is strange that Spohr, a brilliant violinist and a composer best known for his 18 violin concertos and 36 string quartets, should have decided to write such a substantial piece for Harmonie and Janissary-Band. Perhaps his idea was to take advantage while he could of the fast-waning popularity of this kind of ensemble and also further familiarise himself with the wind instruments he would use in his 10 symphonies, his operas and church music in an attempt to match the greatness of his teacher, model and friend Beethoven. It may come as a surprise that so many loud instruments are called for in a Nocturne… But whoever said that nighttime must always be quiet? Alfredo Bernardini 11 Français Menu HARMONIE & TURQUERIES À partir du Moyen-Âge, les ensembles d’instruments à vent ont joué un rôle important dans les sociétés civiles et militaires, en participant à de nombreuses célébrations en plein air. C’était là les fonctions principales de la Alta Cappella médiévale, puis des Piffari de Venise, des Hautbois français, des Stadtpfeifer des pays allemands, qui par la suite se seraient appelés Hautboisten. Il s’agit de groupes composés de professionnels rigoureusement sélectionnés qui jouissaient d’une grande réputation dans leur communauté. Au cours du XVIIIe siècle, probablement à la suite de l’invention et de la rapide introduction dans toute l’Europe des nouveaux hautbois – instruments plus souples en dynamique, en possibilités chromatiques et en tessiture –, ces ensembles de vents prirent place notamment dans les espaces fermés et leur répertoire s’est élargi à la musique d’église, de théâtre et de chambre, tout en continuant à être employés même dans les ensembles militaires et civils. Le point culminant de cette évolution est la fondation, par l’empereur d’Autriche Joseph II à Vienne en 1782, de la Königliche Kaiserliche Harmonie, formation composée de 2 hautbois, 2 clarinettes, 2 cors et 2 bassons. La fonction de cet ensemble appelé Harmonie consistait principalement à jouer au palais les airs d’opéras célèbres que le mécène avait entendus au théâtre peu de temps auparavant, souvent pour faire bonne figure vis à vis de ses hôtes ou pour accompagner un banquet. Il s’agissait d’arrangements préparés en toute hâte par les membres de l’Harmonie eux-mêmes, précisément pour préserver l’actualité de ces musiques. Très vite, pour toute l’aristocratie autrichienne et même en dehors des confins de l’empire, disposer d’une Harmonie de qualité à son propre service signifiait être à la page. Il est donc inévitable que même les compositeurs les plus habiles et/ou les plus célébrés de leur temps devaient s’intéresser à cette formation au point de parvenir à l’employer dans de nouveaux contextes. Presque tous écrivaient des marches militaires, ou dans le style militaire, certains l’utilisaient pour des marches funèbres, d’autres leur consacraient des sérénades et l’employaient même pour la musique d’église, même sans les voix, c’est-à-dire sans texte mis en musique. Si pendant des siècles l’empire ottoman fut considéré une menace pour l’Occident – le siège de Vienne en 1683 constituant le moment culminant de l’affrontement militaire entre les deux sociétés – l’intérêt pour toutes les formes artistiques de l’Orient, peinture, sculpture, architecture, littérature et musique, sans oublier la cuisine, était déjà présent en Europe depuis le XVe siècle. L’amélioration ou la mise en place de nouvelles relations diplomatiques entre Orient et Occident au début du XVIIIe siècle favorisa une activité d’échanges commerciaux qui constitua l’impulsion décisive pour la diffusion 12 d’une des modes les plus exclusives et les plus spectaculaires de tout le XVIIIe siècle : les Turqueries. Voilà que l’on se mit à importer des tapis et des tissus brodés, des bijoux orientaux, à boire du café, à manger de la nourriture épicée. Les nouvelles exotiques comme Les mille et une nuits inspiraient les artistes européens qui, chacun dans leur genre, élaboraient ces récits. Dans le domaine du théâtre et de l’opéra également, les histoires de batailles et de personnages orientaux entraient dans l’imaginaire collectif, comme c’est le cas des nombreux opéras au XVIIIe sur le thème de l’opposition entre Bajazet et Tamerlan. Vers la fin du XVIIIe siècle, de nombreux compositeurs européens se mirent à introduire des éléments turcs ou exotiques dans leur propre musique, aussi bien dans les opéras inspirés par des histoires orientales, que dans la musique instrumentale. En vérité, peu d’éléments de composition de musique orientale sont repris : les concepts d’harmonie et d’intonation de la musique orientale étaient trop éloignés des oreilles occidentales. Mais l’élément qui pour les compositeurs européens représentait le plus la musique des Turcs était l’instrumentation, en particulier celle des mehter, c’est-à-dire les groupes des redoutables Janissaires, qui à l’origine avaient pour rôle de les exciter au combat contre les ennemis : il s’agit de grands ensembles d’instruments à vent retentissants et de percussions de différentes sortes. La zurna, instrument à anche double encore aujourd’hui très employé dans la tradition turque, le davul, un tambour grave, le chapeau chinois (ou pavillon turc/schellenbaum, turkisch crescent) – un bâton avec une multitude de petites clochettes accrochées tout autour – en étaient les instruments les plus typiques. Les compositeurs classiques européens les inséraient dans leurs partitions, par exemple dans les variantes européennes les plus proches, et créaient ainsi une musique puissante et rythmique qui voulait de cette façon caractériser l’exotisme, non parfois sans une touche d’ironie. La Marche turque de Michael Haydn est sans doute le morceau qui témoigne le mieux de la convergence entre Harmonie et Turquerie. Le titre est explicite. À la formation typique de l’Harmonie (2 hautbois, 2 clarinettes, 2 cors et 2 bassons) s’ajoutent ici 2 flûtes, 2 trompettes, les cymbales et le tambour turc. Dans notre interprétation nous avons considéré légitime l’ajout d’un pavillon turc, un instrument qui souvent jouait avec les autres percussions même quand il n’était pas signalé sur la partition. Dans le mouvement harmonique, la seule évocation de l’Orient semble avoir été assurée par la modulation Do-Sol-miSol, pour le reste la musique est fortement rythmique et présente uniquement dans de rares moments de contraste avec de brèves mélodies en piano/doux. Bien qu’étant écrite elle aussi pour un grand ensemble d’instruments à vent, l’introduction à la seconde partie de l’oratorio Les sept dernières paroles du Christ sur la Croix, composé par Joseph Haydn, plus célèbre que son frère aîné, ne pouvait être plus éloignée de la marche précédente. L’oratorio pour solistes, chœur et orchestre est la troisième version 13 Français de cette pièce spirituelle (les deux autres sont écrites pour orchestre et pour quatuor à cordes) et ce n’est que dans celle-ci que Haydn insère l’introduction pour les vents seuls, probablement pour rechercher une couleur instrumentale qui se détache du son de l’orchestre et du chœur du reste de la composition. Le numéro précédent l’introduction de la seconde partie met en musique le texte « Mon Dieu, pourquoi m’as-tu abandonné… » et s’achève par « rien ne nous séparera de toi dans l’éternité ». La réflexion sur l’éternité s’inspire d’une série de longs accords et d’une mélodie simple jouée en mode mineur par deux trombones, instrument à vent d’église par excellence. À ceux-là, Haydn ajoute à la typique formation d’harmonie une flûte et un contrebasson, un instrument d’octave plus basse que le basson ordinaire que l’on avait rapidement intégré dans les partitions viennoises de la fin du XVIIIe siècle. La marche des Janissaires de Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart a été récemment (1980) retrouvée dans une copie manuscrite de l’opéra L’enlèvement au Sérail à la Staatsblibliothek Preussischer Kulturbesitz de Berlin. Dans l’opéra, qui en soi est un des meilleurs exemples de l’époque de la popularité des Turqueries, la marche devait être placée avant le chœur « Singt dem grossen Bassa Lieder » (Acte I, scène 5, début de la scène 6). Dans le livret de la première représentation à Vienne le 16 juillet 1782, on peut lire : « le Pacha Selim et Constance dans une barque de plaisance, précédée d’une autre barque avec la Janitscharenmusik. Une fois arrivés à bon port, les Janissaires entonnent le chœur suivant, puis s’éloignent ». À de nombreuses occasions, Mozart écrivaient les marches de ses opéras au dernier moment, comme c’est le cas avec la marche des prêtres de la Flûte enchantée. Il n’est donc pas étonnant qu’elles ne soient pas intégrées dans les partitions générales de l’opéra. Le concertino de Friedrich Witt, pendant longtemps attribué à Carl Maria von Weber, a été récemment réattribué à son véritable auteur par la musicologue Nessa Glen. Witt fréquentait assidument la cour du prince Löwenstein-Freudenberg-Wertheim près de Würzbourg, et bon nombre de ses compositions se trouvaient il y a peu de temps encore dans la bibliothèque de cette famille. Parmi celles-ci, il y a de nombreuses Parthien, Harmonien, ainsi que le présent concertino pour hautbois, qui semblent s’inspirer du style de son maître Anton Roesler (alias Antonio Rosetti). Si le concerto pour hautbois avec accompagnement d’orchestre (cordes et éventuellement vents) était encore très populaire à la fin du XVIIIe siècle, cette pièce a la rare particularité d’être accompagnée d’une Harmonie, enrichie d’une flûte, un second couple de clarinettes, une trompette, un trombone et un contrebasson. Beaucoup de ces instruments dialoguent de manière récurrente avec le hautbois soliste. La structure en deux seuls mouvements consécutifs, avec un Adagio introductif suivi d’une Polonaise en rondo, est celle que nous retrouvons par la suite dans de nombreuses compositions solistes du XIXe siècle. 14 Comme Mozart avec son Enlèvement au Sérail, Gioacchino Rossini aussi succombait au charme exotique des Turqueries, au point qu’il écrivit deux opéras bouffe à l’atmosphère orientalisante : L’Italienne à Alger et Le Turc en Italie. Ce dernier fut représenté pour la première fois à la Scala de Milan le 14 août 1814, en vérité avec un accueil plutôt froid de la part du public. Quand il fut repris, les années suivantes, à Rome, Venise, Livourne, Paris, Lisbonne et Londres, son succès ne cessa de croître et il entra dans le répertoire des plus grands opéras de tous les temps. La musique du Turc en réalité n’a rien de turc, si ce n’est l’emploi de nombreuses percussions et un usage brillant et diversifié des vents. On dirait presque que chaque emploi soliste des instruments à vent illustre un caractère de l’opéra : par exemple, le cor plaintif dans l’adagio, les bois pimpants dans l’allegro, la fanfare de la trompette. Notre bassoniste Giorgio Mandolesi a réalisé un arrangement de l’ouverture de l’opéra pour orchestre d’harmonie élargi à la flûte, à la trompette, au trombone, au contrebasson, au tuba et aux percussions turques, en s’inspirant des modèles anciens comme ceux de Wenzel Sedlak (1776-1851), clarinettiste d’Harmonie à Vienne et grand « arrangeur ». Gaetano Donizetti n’avait pas encore vingt ans quand il composa sa symphonie pour instruments à vent. Ce morceau, comme d’autres pièces de jeunesse écrites pour les vents, lui servait à améliorer sa connaissance de ces instruments, pour ensuite les employer au mieux dans ses opéras. Une rareté, parmi les musiques pour Harmonie de l’époque, est le choix pour ce morceau de la tonalité mineure, dans la mesure où les vents étaient communément associés à des musiques de divertissement (un des très rares autres exemples d’Harmonie en mineur est la Sérénade en do mineur KV 388 de Mozart). Mais, comme Mozart, Donizetti aussi n’osa pas terminer en mineur et assura une résolution heureuse, un choix probablement nécessaire pour satisfaire les goûts du public de l’époque. La forme en deux temps, avec un bref Andante suivi d’un Allegro, fait penser aux symphonies de ces opéras dont Donizetti allait bientôt devenir un des plus célèbres compositeurs de l’histoire. Même s’il est quasiment inconnu aujourd’hui, le frère aîné de Gaetano, Giuseppe Donizetti, a joui d’une très grande réputation durant sa vie très aisée. Non pas en Europe, mais en Turquie. En 1828, il fut nommé Maître Général de la Musique Impériale Ottomane, au service du Sultan Mahmoud II (18081839). Outre la composition de la Marche de Mahmoud (inclus dans le présent cd) qui pendant des années fut l’hymne impérial ottoman, il se mit à occidentaliser les fanfares militaires de l’Empire, à enseigner la musique aux membres de la famille de Mahmoud, à organiser des saisons d’opéra italien et à accueillir d’illustres musiciens européens en visite à Istanbul, parmi lesquels Franz Liszt. Son prestige lui valut le nom de Donizetti Pacha et son attachement à la Turquie l’incita à y demeurer, jusqu’à sa mort en 1856. 15 Français La précocité de certains compositeurs surprend, surtout quand leurs musiques manifestent une grande habileté et une grande maturité. C’est le cas de Félix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy qui, à 15 ans, pendant un séjour estival aux thermes de Bad Doberan, en mer Baltique près de Rostock, entra en contact avec l’Harmonie locale et décida de composer pour cette formation le Nocturne. La maturité du très jeune musicien surprend quand on écoute les harmonies de l’Andante introductif particulièrement élaboré. Aux 48 premières mesures, pendant lesquelles un thème legato et discursif est joué alternativement par la clarinette et le cor, suit un mouvement ténébreux de bassons et de tubas, entremêlé d’héroïques sonneries de trompettes. L’Allegro vivace intervient pour atténuer le caractère sombre de cet épisode, avec la clarinette comme instrument protagoniste et ses rythmes de fanfare, jouant presque le rôle d’un premier violon. Mendelssohn, dans une lettre à sa sœur Fanny, décrit l’instrument qu’il appelle dans la partition « Corno I di Basso », allant même jusqu’à en dessiner la forme. Il pourrait s’agir d’un cimbasso, c’est-à-dire d’un instrument avec l’embouchure du trombone, mais dont le corps en bois a la forme d’un basson, plus court et plus large cependant en volume : cet instrument allait être abondamment employé dans l’opéra italien durant tout le XIXe siècle pour être ensuite remplacé par l’ophicléide. La sonorité du cimbasso est unique et n’est pas directement comparable à celle du trombone, ni à celle du basson ou du contrebasson ; ce fut une agréable surprise pour nous de la redécouvrir grâce à l’implication de Corrado Colliard qui l’a joué et de Guido Bizzi qui a mis à notre disposition l’instrument original en sa possession. En 1838, Mendelssohn décide d’étoffer l’orchestration du Nocturne, il ajoute de nombreux autres instruments à vent et des percussions et lui donne pour titre Ouverture für Harmoniemusik op. 24 ; toutefois, il n’abandonne pas la première version qu’il demande à l’éditeur Simrock de publier précisément la même année. La différence entre les deux versions peut être considérée comme étant représentative de la distinction entre fanfare et Harmonie. Franz Schubert aussi était très jeune – 16 ans – quand il composa la Marche funèbre Eine kleine Trauer Musik, avec pour sous-titre « Franz Schubert Begräbnis Feyer » (Funérailles de Franz Schubert). Il s’agit d’un morceau surprenant pour plusieurs raisons. Tout d’abord, à cause de la très rare tonalité de mi bémol mineur, ensuite pour l’instrumentation particulière avec deux cors qui jouent une première fois seuls la marche en entier, et affrontent des notes et des intervalles plutôt rares pour des instruments naturels, c’est-à-dire sans piston de l’époque. La marche est ensuite répétée entièrement avec deux clarinettes, deux bassons et deux contrebassons. Il y a différentes théories concernant cette composition. Peu de temps auparavant (mai 1812), un Schubert d’à peine quinze ans a dû affronter la mort de sa mère. Suite à cet épisode, le compositeur se jette tête baissée dans la composition, en négligeant les études du latin et des mathématiques auprès du prestigieux collège 16 Menu Kaiserlich-königlisches Stadtkonvikt (où il était interne depuis 1808), au point d’être sévèrement rabroué par ses tuteurs. La composition de sa propre marche funèbre pourrait avoir été une provocation née de son indifférence envers le collège, comme le prouve son retour dans la maison paternelle en novembre 1813, quelques mois seulement après la composition de ce morceau tragique. Le Nocturne op. 34 de Louis Spohr, avec ses 6 mouvements, est la pièce qui, plus que toutes les autres dans ce programme, unit les caractéristiques de la musique pour Harmonie avec celles des Turqueries. Le sous-titre est explicite : « für Harmonie und Janitscharen-Musik ». Si certains mouvements sont typiquement « turcs » par leur instrumentation et leur caractère – comme la Marche initiale, la Polonaise et le Finale vif – dans les autres (Menuet, Andante et Adagio), les percussions ne jouent pas et on a l’impression d’écouter une musique de chambre raffinée dans laquelle plusieurs instruments s’échangent continuellement les rôles solistes, riches en virtuosité et expressivité, avec encore une fois la clarinette au premier plan. Dans le Trio de la Polonaise apparaît une curieuse partie de cor de postillon qui joue un appel de seulement quatre notes au milieu d’un accompagnement de cuivres, chose qui certainement devait être familière aux auditeurs de l’époque. Il est singulier que Spohr, brillant violoniste et compositeur connu surtout pour ses 18 concertos pour violon et ses 36 quatuors à cordes, se soit engagé à écrire un morceau aussi long pour Harmonie et musique turque. Sans doute a-t-il voulu saisir les derniers instants de popularité de cette formation et aussi approfondir la connaissance des instruments à vent qu’il employa ensuite également dans ses 10 symphonies, ses opéras et dans sa musique sacrée, pour être à la hauteur de son maître, modèle et ami Beethoven. Cela peut surprendre qu’un Nocturne soit joué par autant d’instruments bruyants… mais qui a dit que la nuit doit toujours être silencieuse ? Alfredo Bernardini 18 Menu HARMONIE & TURCHERIE A partire dal Medioevo i gruppi e le bande di fiati ebbero un ruolo di rilievo nelle società civili e militari, partecipando ad occasioni celebrative di vario tipo en plein air. Queste erano le funzioni principali dell’Alta cappella medievale, poi dei Piffari di Venezia, degli Hautbois francesi, degli Stadtpfeifer dei paesi germanici, che successivamente si sarebbero chiamati Hautboisten. Si tratta di gruppi composti da professionisti severamente selezionati che godevano di grande riconoscimento nelle loro comunità. Nel corso del Settecento, probabilmente a seguito dell’invenzione e della rapida introduzione in tutta Europa dei nuovi hautbois – strumenti più versatili in dinamica, possibilità cromatiche ed estensione – i gruppi di strumenti a fiato trovarono spazio anche in ambienti chiusi ed il loro repertorio si allargò alla musica da chiesa, da teatro e da camera, pur continuando ad essere impiegati anche nelle bande militari e civili. Il momento culminante di questa evoluzione è la fondazione, da parte dall’imperatore d’Austria Giuseppe II a Vienna nel 1782, della Königliche Kaiserliche Harmonie, formazione composta da 2 oboi, 2 clarinetti, 2 corni, 2 fagotti. La funzione di quest’Harmonie era principalmente quella di suonare a palazzo le celebri arie d’opera che il mecenate aveva ascoltato in teatro poco prima, spesso per fare bella figura con i suoi ospiti o per accompagnare un banchetto. Si trattava di arrangiamenti approntati in tutta fretta dai membri stessi dell’Harmonie, proprio per garantire l’attualità di queste musiche. Presto, per tutta l’aristocrazia austriaca e anche fuori dei confini dell’Impero, disporre di una Harmonie di qualità al proprio servizio significava poter sfoggiare uno status-symbol à la page. È inevitabile dunque che anche i più abili e/o acclamati compositori dell’epoca si interessassero a questa formazione fino ad arrivare a collocarla anche in nuovi contesti. Quasi tutti scrivevano marce militari o nello stile militare per Harmonie, alcuni la utilizzavano per le marce funebri, c’era chi le dedicava serenate e persino chi la impiegava nella musica da chiesa, anche senza le voci, quindi senza un testo musicato. Se per secoli l’Impero ottomano fu considerato una minaccia per l’Occidente – l’assedio di Vienna del 1683 essendo il momento culminante del confronto militare tra le due società – l’interesse per tutte le forme artistiche d’Oriente tra cui pittura, scultura, architettura, letteratura e musica, senza dimenticare la cucina era già presente in Europa sin dal Quattrocento. Il miglioramento o l’avvio di nuove relazioni diplomatiche tra Occidente ed Oriente all’inizio del Settecento favoriva un’attività di scambi commerciali che costituì l’impulso decisivo per la diffusione di una delle mode più esclusive e dirompenti di tutto il Settecento, quella delle Turcherie. Ecco che si importavano tappeti e tessuti ricamati, gioielli orientali, si beveva caffè, si mangiavano cibi speziati. Le novelle esotiche come Le mille e una notte ispiravano gli artisti Zefiro – Harmonie 20 europei che elaboravano, ognuno nel proprio genere, questi racconti. Anche nel campo del teatro e dell’opera, le storie di personaggi e battaglie orientali entravano nell’immaginario collettivo, come è il caso delle diverse opere settecentesche sul tema del confronto tra Bajazet e Tamerlano. Verso la fine del Settecento anche molti compositori europei si cimentarono con l’introduzione di elementi turchi o esotici nella propria musica, fosse in quella d’opera ispirata a storie orientali, o anche nella musica strumentale. In verità non sono molti gli elementi compositivi della musica orientale che vengono ripresi: i concetti d’armonia e d’intonazione della musica d’Oriente erano troppo distanti dalle orecchie occidentali. Ma l’elemento che per i compositori europei maggiormente rappresentava la musica dei Turchi era la strumentazione, in particolare quella dei mehter, ovvero le bande dei temuti Giannizzeri, che anticamente avevano la funzione di incitarli contro il nemico: si tratta di grandi gruppi di strumenti a fiato fragorosi e di percussioni di vario tipo. La zurna, strumento ad ancia doppia ancora oggi molto usata nella tradizione turca, il davul, tamburo grave, il cappel cinese (o pavillon turc / schellenbaum, turkish crescent) – un bastone con una moltitudine di campanellini appesi tutt’intorno – ne erano gli strumenti più tipici. I compositori classici europei li inserivano nelle loro partiture, magari nelle varianti europee più simili e creavano così una musica forte e ritmica che voleva in questo modo caratterizzare l’esotismo, a volte con un tocco d’ironia. La Marcia Turchesca di Michael Haydn è forse il pezzo che meglio testimonia la convergenza tra Harmonie e Turcherie. Il titolo è esplicito. Alla tipica formazione dell’Harmonie (2 oboi, 2 clarinetti, 2 corni e 2 fagotti) si aggiungono qui 2 flauti, 2 trombe, i piattelli ed il tamburo turchese. Nella nostra esecuzione abbiamo ritenuto legittimo aggiungere un cappel cinese, strumento che spesso suonava insieme alle altre percussioni anche quando non era segnato in partitura. Nel movimento armonico l’unica evocazione dell’Oriente pare essere data dalla modulazione Do-Sol-mi-Sol, per il resto la musica è fortemente ritmica e presenta solo rari momenti di contrasto con brevi melodie in dinamica piano. Pur essendo scritta anch’essa per un grande organico di strumenti a fiato, l’Introduzione alla seconda parte dell’oratorio Le sette ultime parole di Cristo sulla Croce scritta da Joseph Haydn, più conosciuto del fratello maggiore, non potrebbe essere più diversa dalla marcia precedente. L’oratorio per soli, coro e orchestra è la terza versione di questo pezzo spirituale (le prime sono per orchestra e per quartetto d’archi) ed è solo in questa che Haydn inserisce l’introduzione per soli fiati, probabilmente alla ricerca di un colore strumentale che si astrae dal suono dell’orchestra e coro del resto della composizione. Il numero precedente all’Introduzione della seconda parte mette in musica il testo «Dio mio, perché mi ha lasciato…» e termina con «…niente ci separerà da te nell’eternità». La riflessione sull’eternità viene ispirata da una serie di lunghi accordi e da una melodia semplice presentata in tonalità minore da due tromboni, strumenti a fiato da chiesa per eccellenza. Oltre a questi, Haydn aggiunge alla tipica Harmonie un flauto ed il controfagotto, strumento all’ottava bassa del 21 Italiano fagotto ordinario che si era rapidamente inserito nelle partiture viennesi alla fine del Settecento. La Marcia dei Giannizzeri di Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart è stata recentemente (1980) ritrovata in una copia manoscritta dell’opera Il ratto dal Serraglio presso la Staatsbibliothek Preussischer Kulturbesitz di Berlino. Nell’opera, che di per sé è uno dei migliori esempi dell’epoca della popolarità delle Turcherie, la marcia anticiperebbe il coro «Singt dem grossen Bassa Lieder» (Atto I, n. 5, inizio della scena n. 6). Nel libretto della prima esecuzione a Vienna del 16 luglio 1782 si legge: «Bassa Selim e Constanze arrivano in una barca da diporto, preceduta da un’altra con la Janitscharenmusik. Una volta giunti a riva, i Giannizzeri intonano il seguente coro e poi si allontanano». In più occasioni Mozart scriveva le sue marce per le opere all’ultimo momento, come accadde anche con la Marcia dei Sacerdoti nel Flauto Magico. Non c’è dunque da stupirsi se non venivano sempre inserite nelle partiture generali dell’opera. Il Concertino di Friedrich Witt, a lungo attribuito a Carl Maria von Weber, è stato recentemente riattribuito a Friedrich Witt dalla studiosa Nessa Glen. Witt frequentava assiduamente la corte del principe LöwensteinFreudenberg-Wertheim vicino a Würzburg e molte sue composizioni si trovavano fino a poco fa ancora nella biblioteca di quella famiglia. Tra queste, ci sono molte Parthien, Harmonien e il presente Concertino per oboe che sembrano ispirarsi allo stile del suo maestro Anton Roesler (alias Antonio Rosetti). Se il concerto per oboe con accompagnamento d’orchestra (archi ed eventualmente fiati) era ancora molto popolare a fine Settecento, questo pezzo ha la rara particolarità di essere accompagnato da un’Harmonie, rinforzata da un flauto, una seconda coppia di clarinetti, tromba, trombone e controfagotto. Molti tra questi strumenti dialogano ripetutamente con l’oboe solista. La forma in due soli movimenti consecutivi, con un Adagio introduttivo seguito da una Polacca in rondò, è quella che ritroviamo successivamente in molte composizioni solistiche dell’Ottocento. Come Mozart per il suo Ratto dal Serraglio, anche Gioacchino Rossini subiva il fascino esotico delle Turcherie, tanto è vero che scrisse due opere buffe in atmosfere orientaleggianti: L’Italiana in Algeri e Il Turco in Italia. Quest’ultima fu rappresentata per la prima volta alla Scala di Milano il 14 agosto 1814, in verità con un’accoglienza piuttosto fredda da parte del pubblico. Le repliche negli anni immediatamente successivi a Roma, Venezia, Livorno, Parigi, Lisbona, Londra ebbero invece sempre più successo e ne decretarono l’ingresso nel grande repertorio d’opera di tutti i tempi. La musica del Turco in realtà non avrebbe niente di turco, se non l’impiego di tante percussioni ed un uso dei fiati brillante e vario. Sembra quasi che ogni assolo degli strumenti a fiato voglia impersonare un carattere dell’opera: ad esempio, il lamentoso corno nell’Adagio, i pimpanti legni nell’Allegro, la fanfara della tromba. Il nostro fagottista Giorgio Mandolesi ha realizzato un arrangiamento dell’Ouverture dell’opera per Harmonie allargata a flauto, tromba, trombone, controfagotto, cimbasso e percussioni turche, ispirandosi ai modelli storici come quelli di Wenzel Sedlak (1776-1851), clarinettista d’Harmonie a Vienna e grande arrangiatore. 22 Gaetano Donizetti non aveva ancora 20 anni quando scrisse la sua Sinfonia per strumenti a fiato. Questo pezzo, come altre sue musiche di gioventù con i fiati in primo piano, gli serviva per mettere a punto la conoscenza di questi strumenti, per poi utilizzarli al meglio nelle opere. Una rarità, tra le musiche per Harmonie dell’epoca, è la scelta per questo brano della tonalità minore, in quanto i fiati venivano comunemente associati a musiche gioiose e d’intrattenimento (uno dei rarissimi altri esempi di Harmonie in minore è la Serenata in do minore KV388 di Mozart). Ma, come Mozart, anche Donizetti non osa terminare in minore e garantisce un lieto fine, scelta probabilmente obbligata per assecondare i gusti del pubblico dell’epoca. La forma in due tempi, con un breve Andante seguito da un Allegro, fa pensare alle sinfonie di quelle opere di cui a breve Donizetti sarebbe diventato uno dei più famosi compositori della storia. Se anche quasi sconosciuto oggigiorno, il fratello maggiore di Gaetano, Giuseppe Donizetti, godette di una grandissima reputazione durante la sua vita assai agiata. Ma non in Europa: in Turchia. Dal 1828 fu nominato Maestro Generale della Musica Imperiale Ottomana, a servizio del Sultano Mahmud II (1808-1839). Oltre a comporre la Marcia di Mahmud (inserita nel disco) che per molti anni rimase l’inno imperiale ottomano, si adoperò ad occidentalizzare le bande militari dell’Impero, ad insegnare la musica ai membri della famiglia di Mahmud, ad organizzare stagioni di opera italiana e ad ospitare illustri musicisti europei in visita a Istambul, tra cui Franz Liszt. Il suo prestigio gli valse la nomina a Donizetti Pascià ed il suo attaccamento alla Turchia lo indusse a rimanere lì, fino alla morte nel 1856. La precocità di alcuni compositori sorprende, soprattutto quando le loro musiche manifestano grandi abilità e maturità. È il caso di Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy che, a 15 anni durante una vacanza estiva al luogo termale di Bad Doberan, sul Mar Baltico vicino a Rostock, entra in contatto con la Harmonie locale e decide di dedicarle il Nocturno. La maturità del giovanissimo musicista sorprende quando si ascoltano le armonie dell’elaborato Andante introduttivo. Alle prime 48 battute, in cui un tema legato e discorsivo viene alternato tra clarinetto e corno, segue un movimento tenebroso di fagotti e cimbasso, intercalato da eroici squilli di tromba. A risolvere la cupezza di questo episodio interviene l’Allegro vivace che con ritmi di fanfara ha il clarinetto in veste di protagonista, quasi alla stregua di un primo violino. Mendelssohn descrive in una lettera a sua sorella lo strumento che nella partitura chiama «Corno I. di Basso», disegnandone addirittura la forma. Sembra trattarsi di un cimbasso, ovvero di uno strumento con l’imboccatura del trombone, ma col corpo in legno in forma di fagotto, anche se più corto e largo di cameratura: questo strumento sarebbe stato in seguito molto utilizzato nell’opera italiana di tutto l’Ottocento per essere poi sostituito dall’oficleide. La sonorità del cimbasso è unica e non è direttamente paragonabile a quella del trombone, né del fagotto né del controfagotto; è stata una piacevole sorpresa per noi riscoprirla grazie alla dedizione di Corrado Colliard che l’ha suonato e di Guido Bizzi che ne ha messo a disposizione l’originale di sua proprietà. 23 Italiano Menu Nel 1838 Mendelssohn decide di allargare l’orchestrazione del Nocturno, aggiunge numerosi altri strumenti a fiato e le percussioni e lo intitola Ouverture für Harmoniemusik op. 24: tuttavia non abbandona la prima versione che chiede all’editore Simrock di pubblicare proprio nello stesso anno. La differenza tra le due versioni può considerarsi rappresentativa della distinzione tra banda e Harmonie. Anche Franz Schubert era molto giovane – 16 anni – quando scriveva la Marcia Funebre Eine kleine Trauer Musik, con il sottotitolo «Franz Schuberts Begräbnis Feyer» (Funerale di Franz Schubert). Si tratta di un pezzo sorprendente per diverse ragioni. Innanzitutto per la rarissima tonalità di mi bemolle minore, poi per la particolare strumentazione con due corni che suonano una prima volta l’intera marcia da soli, affrontando note ed intervalli assai rari per gli strumenti naturali, ovvero senza valvole dell’epoca. La Marcia viene poi ripetuta completa insieme a due clarinetti, due fagotti e controfagotto. Ci sono diverse teorie riguardo all’origine di questa composizione. Poco prima (maggio 1812), uno Schubert appena quindicenne si era dovuto confrontare con la morte della madre. A seguito di questo episodio il compositore si butta a capofitto nella composizione, trascurando lo studio del latino e della matematica presso il prestigioso collegio Kaiserlich-königliches Stadtkonvikt (dove era internato dal 1808), tanto da essere severamente redarguito dai suoi tutori. La composizione della sua propria marcia funebre potrebbe essere stata una provocazione per l’insofferenza verso il collegio, che è provata dal ritorno alla casa paterna nel novembre 1813, pochi mesi dopo la composizione di questo tragico pezzo. Il Notturno op. 34 di Louis Spohr, con i suoi 6 movimenti, è il pezzo che, più di tutti gli altri in programma, unisce le caratteristiche della musica per Harmonie con le Turcherie. Il sottotitolo è esplicito: «für Harmonie und Janitscharen-Musik». Se alcuni movimenti sono tipicamente ‘turchi’ per strumentazione e carattere – come la Marcia iniziale, la Polacca ed il Finale vivace – negli altri (Minuetto, Andante e Adagio) le percussioni non suonano e sembra di ascoltare una raffinata musica da camera in cui diversi strumenti si scambiano continuamente i ruoli solistici ricchi di virtuosismo ed espressione, con il clarinetto ancora una volta in primo piano. Nel Trio della Polacca appare una curiosa parte di corno di postiglione, chiamato anche corno di posta, che suona una chiamata di sole quattro note in mezzo ad un accompagnamento di soli ottoni, cosa che certamente doveva essere familiare agli ascoltatori dell’epoca. È singolare che Spohr, brillante violinista e compositore conosciuto soprattutto per i suoi 18 concerti per violino e 36 quartetti per archi, si sia impegnato a scrivere un pezzo così esteso per Harmonie e musica turca. Forse volle cogliere l’ultimo momento di popolarità di questa formazione e anche approfondire la conoscenza degli strumenti a fiato che poi impiegò anche nelle 10 sinfonie, nelle opere e nella musica sacra, per essere all’altezza del suo maestro, modello ed amico Beethoven. Può sorprendere che un Notturno venga suonato da così tanti strumenti fragorosi… ma chi dice che la notte debba essere sempre silenziosa? Alfredo Bernardini −Vivaldi Concerti per fagotto Alberto Grazzi Zefiro −Concerti veneziani per oboe Albinoni Bigaglia Marcello Platti Sammartini Vivaldi Alfredo Bernardini Zefiro A 365 1 CD −Telemann Ouvertures à 8 A 380 1 CD −Handel The Musick for the Royal Fireworks Zefiro Alfredo Bernardini Zefiro Alfredo Bernardini A 371 1 CD −Mozart En Harmonie Zefiro Alfredo Bernardini A 374 1 CD A 386 1 CD Iconography —digipack Front cover: Katherine Renee, Up And Away. ©Katherine Renee Photography Iconography —booklet Pages 17 and 19, Zefiro during the recording sessions, January 2015. ©Arnold Ritter Pages 24-25, the instruments. ©Arnold Ritter Translations Italian–English: Avril Bardoni Italian–French: Jean-François Lattarico Editing: Donatella Buratti Graphic design: Mirco Milani Cover design: GraphX Acknowlegements Thanks are due to Prof. Emre Araci (Istanbul) and Prof. Michele Bernardini (Rome) for historical and musicological help and advice. And to the following for providing various instruments: Don Raimondo Perathoner (doublebassoon, property of the Canonica di Santa Cristina di Val Gardena); Guido Bizzi (cimbasso); Gino Maini (flauto terzino); Nicola Moneta (cappel cinese). Arcana is a label of OUTHERE MUSIC FRANCE 16, rue du Faubourg Montmartre 75009 Paris www.outhere-music.com www.facebook.com/OuthereMusic Artistic Director: Giovanni Sgaria Listen to samples from the new Outhere releases on: Ecoutez les extraits des nouveautés d’Outhere sur : Hören Sie Auszüge aus den Neuerscheinungen von Outhere auf: Listen to samples from the new Outhere releases on: www.outhere-music.com Ecoutez les extraits des nouveautés d’Outhere sur : Hören Sie Auszüge aus den Neuerscheinungen von Outhere auf: www.outhere-music.com

Scaricare