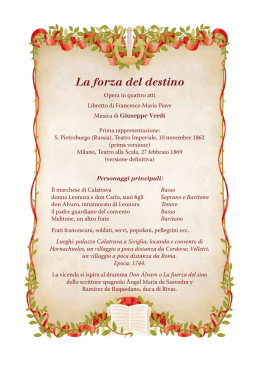

CDS 512/1-3 D D D DIGITAL LIVE RECORDING GIUSEPPE VERDI (Busseto, 1813 - Milan, 1901) LA FORZA DEL DESTINO Opera in four acts - Libretto by Francesco Maria Piave - Edition: Kalmus Leonora Don Alvaro Don Carlo Padre Guardiano Fra’ Melitone Preziosilla Il Marchese di Calatrava Un Alcade Chirurgo Mastro Trabuco Curra Susanna Branchini Renzo Zulian Marco Di Felice Paolo Battaglia Paolo Rumetz Tiziana Carraro Giuseppe Nicodemo Luca Dall’Amico Romano Franci Antonio Feltracco Silvia Balistreri ORCHESTRA FILARMONIA VENETA “G. F. MALIPIERO” Conductor: Lukas Karitynos CORO DEL TEATRO SOCIALE DI ROVIGO Chorus Master: Giorgio Mazzucato Corps de ballet Compagnia Fabula Saltica CD 1 1 69:45 - Ouverture 7:41 ACT ONE 2 - Buona notte, mia figlia (Calatrava) 3 - Temea restasse qui fino a domani (Curra) 4 - Me, pellegrina ed orfana (Leonora) 5 - M’aiuti, signorina, più presto andrem (Curra) 6 - É tardi (Leonora) 2:19 1:52 4:06 7:41 2:24 ACT TWO 7 - Holà, holà, holà! (Chorus) 8 - Al suon del tamburo (Preziosilla) 9 - Padre Eterno Signor (Chorus of Pilgrims) 10 - Viva la buona compagnia! (Don Carlo) 11 - Poiché imberbe l’incognito (Don Carlo) 12 - Sta bene (Alcalde) 13 - Sono giunta! (Leonora) 14 - Madre, pietosa Vergine (Leonora) 15 - Chi siete? (Melitone) 16 - Chi mi cerca? (Father Superior) 17 - Più tranquilla, l’alma sento (Leonora) 18 - Se voi scacciate questa pentita (Leonora) 3:23 3:20 3:55 2:07 3:45 3:24 1:53 5:29 2:31 2:24 4:01 7:24 CD 2 1 2 40:19 - Organ music - Il santo nome di Dio Signore (Father Superior) ACT THREE 3 - Attenti al gioco (Chorus) 4 - O tu che in seno agli angeli (Don Alvaro) 2 3:13 7:38 7:07 3:22 5 6 7 8 9 10 - Al tradimento (Don Carlo) - Amici in vita e in morte (Don Carlo/ Don Alvaro) - Piano... qui posi... (Don Carlo) - Solenne in quest’ora (Don Alvaro) - Morir! Tremenda cosa! (Don Carlo) - Urna fatale del mio destino (Don Carlo) CD 3 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1:50 2:58 1:21 4:15 2:21 6:10 66:37 - Compagni, sostiamo (Chorus) - Nè gustare m’è dato (Don Alvaro) - Sleale! Il segreto fu dunque violato? (Don Alvaro) - Lorché pifferi e tamburi (Chorus) - Qua, vivandiere, un sorso (Soldiers) - Pane, pan per carità! (Peasants) - Nella guerra è la follia (Chorus) - Toh! Toh! Poffare il mondo! (Melitone) - Lasciatelo ch’ei vada (Preziosilla) ACT FOUR 10 - Fate, la carità (Chorus of Beggars) 11 - Auf! Pazienza non v’ha che basti (Melitone) 12 - Del mondo i disinganni (Father Superior) 13 - Giunge qualcuno, aprite (Father Superior) 14 - Invano Alvaro ti celasti al mondo (Don Carlo) 15 - Col sangue sol cancellasi (Don Carlo) 16 - Pace, pace, mio Dio! (Leonora) 17 - Io muoio! Confessione! (Don Carlo) 18 - Non imprecare; umiliati (Father Superior) 3 2:21 1:30 7:00 2:25 2:40 2:53 2:20 3:47 3:42 6:45 2:28 1:54 1:13 1:55 7:37 6:19 3:29 6:09 u l finire degli anni Cinquanta dell’Ottocento Verdi smise sostanzialmente di comporre musica: la sua attenzione era infatti interamente rivolta agli avvenimenti che avrebbero condotto all’unità d’Italia nel 1861. Verdi fu da sempre energico fautore dell’unificazione dei vari stati e staterelli italiani sotto un’unica bandiera e, come è noto, moltissime sue opere contengono forti ed espliciti riferimenti patriottici. Fu quindi estremamente naturale per Verdi farsi assorbire dagli accadimenti politici e militari di quegli anni. Egli era, inoltre, una delle personalità più rinomate e autorevoli della penisola e un suo ingresso in politica veniva caldeggiato da diverse parti. Fu così che, anche se malvolentieri, Verdi divenne deputato del primo parlamento italiano, incarico che mantenne fino al 1865. A solleticare la fantasia di Verdi giunse, all’inizio del 1861, una lettera del celebre tenore romano Enrico Tamberlick, in quel periodo impegnato a Pietroburgo. Egli, in accordo con le autorità musicali russe e dietro suggerimento di Mauro Corticelli (un agente teatrale bolognese), propose al compositore di scrivere una nuova opera per il teatro imperiale: “Libera a voi la scelta dell’argomento, e del poeta, a voi la richiesta delle condizioni, a voi la proprietà dell’opera”. Verdi inizialmente propose come soggetto il Ruy Blas che però non piacque al Tamberlick. Questo rifiuto rallentò le trattative e rischiò di far naufragare l’intero progetto, ma le parti seppero fortunatamente arrivare a un accordo e la scelta di Verdi cadde su Don Alvaro o La Fuerza del Sino, un dramma dello spagnolo Angel Perez de Saavedra. Verdi non perse tempo e contattò Piave che si mise subito al lavoro. Come sempre le correzioni e i richiami alla concisione e alla brevità furono parecchi, ma l’opera fu completata abbastanza rapidamente (salvo l’orchestrazione) nel novembre 1861, in tempo per la tra- sferta in Russia. Una volta giunto a Pietroburgo con la moglie Giuseppina Strepponi, Verdi si trovò di fronte alle cattive condizioni di salute della protagonista Emilia La Grua, imprevisto che fece slittare la “prima” di quasi un anno. Egli ebbe dunque tempo per trovare un soprano all’altezza della vertiginosa parte di Leonora (la francese Caroline Barbot), per scrivere l’Inno delle Nazioni per l’Esposizione Universale di Londra, e per chiedere e ottenere che a Pietroburgo la Barbot cantasse prima nel Ballo in Maschera e poi nella Forza. La sera del 10 novembre 1862 La Forza del Destino andò finalmente in scena al Teatro Imperiale di Pietroburgo. Il successo fu pieno e convincente, l’esecuzione “buonissima”, stando a quanto Verdi stesso scrisse a Tito Ricordi nel suo telegrafico resoconto della serata. Lo Zar Alessandro II, assente alle prime recite per una malattia, fu presente alla quarta rappresentazione e fece personalmente chiamare il Maestro per complimentarsi con lui. Di lì a pochi giorni lo Zar insignerà Verdi dell’Ordine Imperiale e Reale di San Stanislao. La Forza del Destino è una delle opere verdiane dalla storia più tormentata, tanto che, nella sua prima versione, è ancora abbastanza lontana da quella che siamo abituati ad ascoltare oggi. A parte gli aggiustamenti avvenuti in corso d’opera, la prima modifica sostanziale risale al 1863, quando il compositore decise di abbassare di un tono la cabaletta dell’aria del tenore perché “nissuno potrebbe eseguire quella che fu scritta per Tamberlick”, voce dotata di eccezionale estensione nel registro acuto. Questo brano verrà poi soppresso nella versione definitiva dell’opera. Verdi non era poi soddisfatto del finale che nella sua prima versione prevedeva il suicidio di Don Alvaro. Vari impegni non consentirono però al Maestro di porre energicamente mano allo spartito e le modifiche si fecero attendere per altri sei anni. Arriviamo così alla fine del 1868, quando Tito Ricordi S 4 intravide, nella rivisitazione della Forza, la possibilità di riportare Verdi alla Scala. Francesco Maria Piave versava in gravi condizioni di salute e le modifiche testuali furono affidate ad Antonio Ghislanzoni, librettista già piuttosto affermato che, negli anni successivi, avrebbe scritto per Verdi anche il libretto di Aida e la versione italiana del Don Carlos. La “nuova” Forza, nell’edizione oggi abitualmente eseguita, con cambiamenti al terzo atto, al quarto atto e al finale, andò in scena al Teatro alla Scala il 27 febbraio 1869 ottenendo ampio consenso di pubblico e di critica. Alcuni sollevarono riserve sulla commistione tra il tragico della vicenda principale e il comico di alcuni personaggi. Verdi difese sempre questa scelta, quasi shakespeariana potremmo dire, che però non aveva in Italia una consolidata tradizione. La Forza del Destino è comunque di sua natura una creazione sperimentale, di un compositore maturo ma ancora teso alla ricerca di nuovi stimoli e nuove sfide. Accanto a pagine di assoluto e ieratico splendore (si pensi alla magnifica e ampia Sinfonia d’apertura, alla celebre scena della Vergine degli Angeli – interamente ideata, anche sul piano librettistico, dallo stesso Verdi – alla struggente melodia di Leonora, Pace mio Dio, del quarto atto) vengono collocate scene e personaggi comici ma nondimeno splendidi, primo fra tutti Fra’ Melitone, una delle creature più riuscite dell’intero teatro verdiano. Straordinaria è anche la resa del coro, lontanissimo dall’essere concepito in modo monolitico ma anzi dipinto in modo vario, sfaccettato e complesso. L’orchestrazione, invece, non è particolarmente ardita e non è sempre all’altezza degli intenti drammatici desiderati dal compositore. L’opera fu poi rappresentata a Brescia, a Parigi, ad Anversa (per cui Verdi scrisse una versione apposita che rimase in uso fino al 1931), in molte altre località europee e d’oltreoceano. La Forza fu una delle creazioni verdiane più trascurate della prima metà del Novecento ma si impose stabilmente nel repertorio a partire dagli anni Cinquanta, divenendo terreno di conquista dei più grandi cantanti lirici del dopoguerra. Stefano Olcese 5 owards the end of the 1850s Verdi virtually stopped composing, his attention being entirely focussed on the events that would lead, in 1861, to a unified Italy. Verdi had forever been a supporter of the ideal of bringing together the peninsula’s various little kingdoms under one banner and, as it is known, many of his operas contain strong and explicit patriotic allusions. It was thus only natural for the composer to become engrossed in those years’ political and military events. He was, moreover, one of the most famous and authoritative figures of the peninsula, and many wanted him to enter into politics. Thus Verdi became, even though a bit reluctantly, a member of the first Italian parliament, a position he kept until 1865. At the beginning of 1861, a letter from the famous Roman tenor Enrico Tamberlick, then engaged in St Petersburg, came to tickle the composer’s imagination again. In agreement with the Russian music authorities and on the suggestion of Mauro Corticelli (an impresario from Bologna), the tenor asked the composer to write a new opera for the imperial theatre: “You shall have free choice of subject and librettist, of requesting your own conditions, and full ownership of the work”. Verdi initially proposed Ruy Blas, but Tamberlick did not like it. His refusal slowed down negotiations and risked making the project fail, but fortunately an agreement was found, and Verdi’s choice finally fell on Don Alvaro o La Fuerza del Sino, a tragedy by the Spaniard Angel Perez de Saavedra. Without delay, Verdi contacted Piave, who set to work right away. As usual corrections and appeals to concision were necessary, but the opera was completed rather quickly (except for the orchestration), and by November 1861 everything was ready for the Russian transfer. Having arrived in St. Petersburg with his wife Giuseppina Strepponi, Verdi had to face the problem of Emilia La Grua’s (the protagonist) poor health, which caused the première to be postponed by almost one year. Verdi thus had all the time to find a suitable replacement for the dazzling part of Leonora (the French soprano Caroline Barbot), to write the Inno delle Nazioni for the London Internatinal Exhibition, and to request and obtain that Barbot sing, in St. Petersburg, in Ballo in Maschera prior to Forza del Destino. On the evening of 10th November 1862 La Forza was finally staged at St. Petersburg’s Imperial Theatre, obtaining a resounding success. The performance was “excellent”, according to what Verdi wrote to Tito Ricordi in his telegraphic account of the soirée. The Czar Alexander II, who could not see the first performances due to illness, attended on the fourth evening, and summoned the Maestro to congratulate him in person. A few days later he would confer on him the Order of St. Stanislav. La Forza del Destino was one of Verdi’s more tormented operas in the making, and its first version is quite different from the one we are used to hearing today. In addition to the adjustments made as the work was being composed, a first substantial change was made in 1863, when the composer decided to lower by one tone the cabaletta of the tenor’s aria, because “no one would be able to sing what had been written for Tamberlick”, whose voice had exceptional extension in the high register. The piece would later be eliminated in the final version of the opera. Verdi, moreover, was not satisfied with the finale, which originally saw Don Alvaro’s suicide. Various engagements, however, prevented the composer from revising the score, and six years went by before more changes were made. We thus arrive at the end of 1868, when Tito Ricordi envisioned the chance of bringing Verdi back to La T 6 Scala with a revival of La Forza. Francesco Maria Piave was seriously ill and modifications to the text were entrusted to Antonio Ghislanzoni, a fairly renowned librettist who, in following years would write for Verdi the libretto of Aida and the Italian version of Don Carlos. The ‘new’ Forza, in the version which is usually performed today, with the changes to Act three, Act four and the finale, was first performed at Teatro alla Scala on 7th February 1869, and was well received both by audiences and critics. A few people expressed doubts about the mixture of the plot’s tragic elements and some characters’ comic traits; Verdi always defended this choice, which was almost Shakespearean but had no tradition in Italy. La Forza del Destino is, indeed, an experimental creation, by a composer who was already mature but still looking for new incentives and challenges. Beside pages of absolute and hieratic splendour (for example the beautiful and ample opening Symphony, the famous scene of the Lady of the Angels – entirely conceived by Verdi, even textually – and Leonora’s poignant melody Pace mio Dio in Act four), there are scenes and characters that are delightfully funny, first of all Fra’ Melitone, one of Verdi’s most successful creations. The composer’s choral writing is also quite extraordinary; far from being conceived as a monolithic bloc, the chorus is treated in a variegated and complex way. The orchestral writing, on the other hand, is not very enterprising and does not always correspond to the composer’s dramatic objectives. Later the opera was performed in Brescia, Paris, Antwerp (for which Verdi wrote a special version that was used up to 1931) and several other European and American cities. Throughout the first half of the 1900s La Forza del Destino was one of the more neglected of Verdi’s operas, but from the 1950s it entered the repertoire, and became a land of conquest for all the best lyrical singers of the post war period. Stefano Olcese (Translated by Daniela Pilarz) Lukas Karitynos 7 egen Ende der Fünfzigerjahre des 19. Jahrhunderts unterbrach Verdi im wesentlichen sein musikalisches Schaffen, denn seine Aufmerksamkeit war zur Gänze auf die Ereignisse gerichtet, die 1861 zur Einigung Italiens führen sollten. Verdi war immer schon ein energischer Anhänger der Vereinigung der verschiedenen italienischen Staaten und Kleinstaaten zu einer einzigen Nation, und viele seiner Opern enthalten bekanntlich starke, ausdrückliche patriotische Bezüge. Es war für den Komponisten daher völlig natürlich, sich von den politischen und militärischen Ereignissen jener Jahre in Anspruch nehmen zu lassen. Außerdem war er eine der angesehensten Persönlichkeiten der Halbinsel, und sein Eintritt in die Politik wurde von verschiedenen Seiten befürwortet. So wurde Verdi, wenn auch ungern, zum Abgeordneten des ersten italienischen Parlaments, welche Aufgabe er bis 1865 beibehielt. Anfang 1861 war es ein Schreiben des berühmten römischen Tenors Enrico Tamberlick, der damals in St. Petersburg engagiert war, das die Phantasie des Komponisten entzündete. In Abstimmung mit den russischen Musikbehörden und auf Empfehlung von Mauro Corticelli (einem Bühnenagenten aus Bologna) schlug er Verdi vor, für die kaiserliche Bühne eine neue Oper zu schreiben: „Sie sind in der Wahl des Themas und des Librettisten frei, Ihnen stehen die Bedingungen zu, das Werk bleibt Ihr Eigentum“. Verdi schlug anfänglich Ruy Blas als Sujet vor, das Tamberlick aber nicht gefiel. Diese Zurückweisung verlangsamte die Verhandlungen und riskierte, den ganzen Plan zunichte zu machen. Die Parteien kamen aber glücklicherweise zu einer Abmachung, und Verdis Wahl fiel auf Don Alvaro o La Fuerza del Sino, ein Drama des Spaniers Angel Perez de Saavedra. Der Komponist verlor keine Zeit und kontaktierte den Librettisten Francesco Maria Piave, der sich sofort an die Arbeit machte. Wie immer gab es viele Korrekturen und Mahnungen zu Knappheit und Kürze, doch wurde die Oper (außer der Orchestrierung) im November 1861 rechtzeitig für die Reise nach Rußland beendet. In St. Petersburg mit seiner Frau Giuseppina Strepponi angelangt, sah Verdi sich dem schlechten Gesundheitszustand der Protagonistin Emilia La Grua gegenüber. Dieses unvorhergesehene Ereignis führte zur Verschiebung der Uraufführung um fast ein Jahr. Der Komponist hatte somit Zeit, um einen Sopran zu finden, der auf der Höhe für die schwindelerregende Rolle der Leonora war (die Französin Caroline Barbot), den Inno delle Nazioni für die Londoner Weltausstellung zu schreiben und zu verlangen, daß die Barbot zuerst in Un Ballo in Maschera und dann in der Forza del destino auftreten sollte, was ihm gewährt wurde. Am 10. November 1862 ging La Forza del Destino endlich über die Bühne des kaiserlichen Theaters in Petersburg. Es wurde ein voller, überzeugender Erfolg und war auf Grund dessen, was Verdi selbst in seinem telegraphischen Bericht an Tito Ricordi über den Abend schrieb, eine „sehr gute“ Wiedergabe. Zar Alexander II., der wegen Krankheit nicht bei den ersten Vorstellungen erschienen war, besuchte die vierte und ließ den Meister persönlich kommen, um ihm zu gratulieren. Wenige Tage darauf sollte er Verdi den Kaiserlich-königlichen St. Stanislaus-Orden verleihen. La forza del Destino ist eine der Opern Verdis mit der kompliziertesten Geschichte und in der ersten Fassung noch recht weit von dem entfernt, das zu hören wir heute gewöhnt sind. Abgesehen von den Korrekturen, die während der Aufführungsserie stattfanden, geht die erste wesentliche Änderung auf 1863 zurück, als der Komponist beschloß, die Cabaletta der Arie des Tenors um einen Ton tiefer zu setzen, weil „niemand die für Tamberlick geschriebene singen G 8 könnte“; die Stimme dieses Tenors hatte eine außergewöhnlich ausgeprägte Höhenlage. Dieses Stück wurde dann in der endgültigen Fassung des Werks gestrichen. Verdi war außerdem mit dem Finale nicht zufrieden, das in der ersten Fassung Don Alvaros Selbstmord vorsah. Verschiedene Verpflichtungen erlaubten es dem Meister aber nicht, sich energisch mit der Partitur zu beschäftigen, sodaß Änderungen erst nach weiteren sechs Jahren erfolgten. So war es bereits Ende 1868, als Tito Ricordi in einer Bearbeitung der Forza del Destino die Möglichkeit sah, Verdi wieder an die Scala zu bringen. Piave war schwer erkrankt, sodaß die Textänderungen Antonio Ghislanzoni anvertraut wurden, einem bereits recht erfolgreichen Librettisten, der in den Jahren darauf für Verdi auch das Textbuch von Aida und die italienische Fassung von Don Carlos schreiben sollte. Die „neue“ Forza del Destino ging in der heute üblicherweise gespielten Fassung (mit Änderungen im dritten und vierten Akt und im Finale) am 27. Februar 1869 im Teatro alla Scala mit großem Erfolg seitens Publikum und Kritik über die Bühne. Gegenüber Vorbehalten hinsichtlich der Mischung zwischen der Tragik der Haupthandlung und der Komik einiger Figuren verteidigte Verdi diese fast shakespearehafte Entscheidung immer, die in Italien aber keine gefestigte Tradition hatte. La Forza del Destino ist jedenfalls ihrer Natur nach die experimentelle Schöpfung eines reifen Komponisten, der aber noch auf der Suche nach neuen Anregungen und Herausforderungen ist. Neben Stellen von absoluter, feierlicher Schönheit (man denke an die wunderbare, lange Ouvertüre, an die berühmte Szene der Vergine degli Angeli - die, auch auf Ebene des Librettos, zur Gänze von Verdi selbst entworfen wurde -, an Leonoras verzehrende Melodie Pace mio dio im vierten Akt) gibt es komische, aber deshalb nicht weniger prachtvolle Szenen und Figuren. Die wichtigste von ihnen ist Fra’ Melitone, eines der gelungensten Geschöpfe der gesamten Produktion Verdis. Außerordentlich ist auch der Anteil des Chors, der von einer monolithischen Konzeption weit entfernt ist und im Gegenteil auf vielfältige, nuancierte und komplexe Art geschildert wird. Die Orchestrierung hingegen ist nicht besonders kühn und nicht immer auf der Höhe der vom Komponisten gewünschten dramatischen Absichten. Die Oper wurde dann in Brescia, Paris, Antwerpen (für dieses Haus schrieb Verdi eine eigene Fassung, die bis 1931 in Verwendung blieb), vielen anderen europäischen Städten und in Übersee gegeben. Sie war eine der in der ersten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts am stärksten vernachlässigten Schöpfungen Verdis, faßte aber ab den Fünfzigerjahren im Repertoire fest Fuß und wurde von den größten Opernsängern der Nachkriegszeit für sich erobert. Stefano Olcese (Übersetzung: Eva Pleus) 9 la fin des années dix-huit cent cinquante, Verdi arrêta en substance d’écrire de la musique, son attention étant entièrement tournée vers les événements qui allaient donner naissance en 1861 à l’unité de l’Italie. Depuis toujours, Verdi soutenait l’idée de l’unification des divers états d’Italie, petits et grands, sous un seul drapeau ; comme chacun sait, nombre de ses œuvres contiennent des références patriotiques fortes et explicites. Il était donc tout naturel pour Verdi de concentrer son attention sur les événements politiques et militaires de ces années-là. De plus, il était l’une des personnalités les plus renommées et influentes de la péninsule italienne, et de toutes parts l’on aspirait à ce qu’il entre en politique. C’est ainsi que Verdi se retrouva, un peu malgré lui, député du premier parlement italien jusqu’en 1865. Au début de l’année 1861, l’imagination de Verdi fut chatouillée par une lettre du célèbre ténor romain Enrico Tamberlick, engagé à l’époque à SaintPétersbourg. Avec l’accord des autorités musicales russes et sur les conseils de Mauro Corticelli (un agent théâtral de Bologne), il proposait au compositeur d’écrire un nouvel opéra pour le théâtre impérial : «Vous êtes libre de choisir le sujet et le poète, vous posez vos conditions et vous êtes propriétaire de l’œuvre ». Au départ, Verdi proposa le sujet de Ruy Blas, mais il ne plaisait pas à Tamberlick. Ce refus ralentit les négociations et risqua de faire échouer le projet, mais les parties surent heureusement parvenir à un accord et le choix de Verdi tomba sur Don Alvaro o La Fuerza del Sino, un drame de l’écrivain espagnol Angel Perez de Saavedra. Verdi ne perdit pas de temps et prit contact avec Piave qui se mit tout de suite au travail. Comme toujours, les corrections et les appels à la concision et à la brièveté furent nombreux, mais l’œuvre fut achevée assez rapidement (excepté l’orchestration) en novembre 1861, à temps pour le départ en Russie. Une fois arrivé à Saint-Pétersbourg avec son épouse Giuseppina Strepponi, Verdi dut faire face au mauvais état de santé de la protagoniste Emilia La Grua ; cet imprévu fit reculer la première de presque un an. Il eut donc le temps de trouver une soprano à la hauteur de la partie vertigineuse de Leonora (la française Caroline Barbot), d’écrire l’Hymne des Nations pour l’Exposition Universelle de Londres, et de demander et obtenir que Barbot chante à Saint-Pétersbourg d’abord dans Un Ballo in Maschera puis dans La Forza del Destino. Le soir du 10 novembre 1862, La Forza del Destino fut donc représentée au Théâtre Impérial de SaintPétersbourg et obtint un franc succès ; d’après le compte-rendu de la soirée que fit Verdi dans une lettre adressée à Tito Ricordi, l’exécution avait été «très bonne ». Le Tzar Alexandre II, indisposé le soir de la première, se montra lors de la quatrième représentation et fit appeler Verdi personnellement pour le féliciter. Quelques jours plus tard, le Tzar décora le compositeur de l’Ordre Impérial et Royal de Saint Stanislas. L’histoire de La Forza del Destino est une des plus complexes des œuvres de Verdi : sa première version est encore assez éloignée de celle que nous connaissons aujourd’hui. Excepté les modifications apportées pendant la composition de l’œuvre, la première modification substantielle date de 1863, quand le compositeur décida de baisser d’un ton la cabalette de l’aria du ténor parce que «personne ne pourrait chanter ce qui a été écrit pour Tamberlick », qui avait une voix exceptionnellement étendue dans le registre aigu. Cette aria fut ensuite supprimée définitivement dans la version finale de l’opéra. Verdi n’était pas satisfait du finale qui, dans la première version, prévoyait le suicide de Don Alvaro. Pendant plusieurs années, les engagements A 10 professionnels du compositeur l’empêchèrent de reprendre la partition en main, si bien que les modifications ne furent apportées que six ans plus tard. En 1868, Tito Ricordi, revisitant La Forza del Destino, entrevit la possibilité de ramener Verdi à la Scala. En raisons du très mauvais état de santé de Francesco Maria Piave, les modifications du texte furent confiées à Antonio Ghislanzoni, librettiste déjà assez connu qui, dans les années suivantes, allait écrire pour Verdi le livret de Aida et la version italienne de Don Carlos. La «nouvelle » Forza del Destino, dans la version que nous connaissons aujourd’hui – avec des modifications aux troisième et quatrième acte et dans le finale – fut mise en scène le 27 février 1869 à la Scala et obtint un vif succès auprès du public et de la critique. D’aucuns émirent des réserves sur le mélange entre le tragique de l’histoire et le caractère comique de certains personnages. Verdi a toujours défendu ce choix presque shakespearien, mais qui ne vantait pas en Italie une solide tradition. La Forza del Destino est cependant, de par sa nature, une création expérimentale d’un compositeur qui, quoique parvenu au sommet de sa maturité, était toujours en quête de nouvelles inspirations et de nouveaux défis. Des pages d’une splendeur absolue et hiératique (comme la magnifique Symphonie d’ouverture ou la célèbre scène de la Vergine degli Angeli – entièrement conçue, paroles comprises, par Verdi – ou encore la mélodie poignante de Leonora, Pace mio Dio, au quatrième acte) sont entrecoupées de scènes et de personnages à la fois comiques et splendides, comme Fra’ Melitone, une des créatures les plus réussies de tout le théâtre de Verdi. L’extraordinaire écriture chorale n’est jamais conçue de façon monolithique mais plutôt multicolore, à facettes multiples et complexe. En revanche, l’orchestration n’est pas particulièrement audacieuse et ne se montre pas toujours à la hauteur des intentions dramatiques voulues par le compositeur. L’opéra fut ensuite représenté à Brescia, à Paris, à Anvers (à cette occasion Verdi écrivit une version spéciale qui fut utilisée jusqu’en 1931) et dans nombre d’autres villes d’Europe et d’Amérique. La Forza del Destino fut une des créations de Verdi les plus négligées durant la première moitié du vingtième siècle, mais l’œuvre finit pas s’imposer de façon stable à partir des années Cinquante et par être convoitée par les plus grandes voix de l’opéra de l’aprèsguerre. Stefano Olcese (Traduit par Cécile Viars) 11 contiene un ritratto di sua sorella, Leonora. Comprende dunque chi sia l’uomo che l’ha salvato. E, non appena il ferito si è ripreso, si sfidano a duello mortale. Ma gli uomini hanno appena messo mano alle spade quando sopraggiunge una ronda. Devono fuggire per non essere arrestati. Sul campo sorge il nuovo giorno. Vivandiere e soldati cominciano la loro quotidiana attività. TRAMA Atto I In Spagna e in Italia verso la metà del secolo XVIII. Don Alvaro cerca di rapire donna Leonora, figlia del marchese di Calatrava; ma è scoperto dal padrone di casa, che non lo vuole come genero perché non è di rango pari al suo. Il giovane prende su di sé l’intera colpa del tentato rapimento scagionando completamente la fanciulla. Getta a terra la pistola che teneva in mano, ma parte accidentalmente un colpo che uccide il marchese. Morendo, questi maledice la figlia. Atto IV Convento degli Angeli. Nel chiostro, i poveri aspettano il loro turno per ottenere un pasto, distribuito da Fra Melitone. Tra i religiosi c’è anche un nuovo confratello, padre Raffaele, nome sotto il quale si cela Don Alvaro. Don Carlo riesce a rintracciarlo, e lo sfida nuovamente a un confronto all’ultimo sangue. Prima dello scontro, Padre Raffaele si spreta, per non commettere sacrilegio; il duello si risolve con la vittoria di Don Alvaro, che ferisce mortalmente il suo avversario. Questi chiede un confessore, e Don Alvaro si avvicina, per cercarlo, all’ingresso dell’eremo. E’ quello in cui vive Leonora. I due si riconoscono; l’uomo la mette al corrente degli ultimi tragici fatti. Leonora accorre presso il fratello che, nell’ultimo anelito di vita, compie il suo terribile giuramento trafiggendola con la spada. Alvaro la sorregge, mentre il Padre Guardiano le impartisce l’estrema benedizione e li conforta negli ultimi momenti. Atto II Leonora è alla ricerca di Alvaro. Sperando di incontrarlo, si traveste da studente ed entra in un’osteria. Ma non lo trova. La zingara Preziosilla si accorge dello stratagemma, però non dice nulla che possa tradire Leonora. Nell’osteria entra anche il fratello di quest’ultima, Carlo. Sta cercando i due innamorati e ha giurato di ucciderli entrambi. Angosciata, Leonora si rifugia al Convento della Madonna degli Angeli. Accolta da Fra Melitone, è condotta dal Padre Guardiano. Solo lui saprà la sua vera identità. La giovane si ritira in un eremo non lontano dal convento; nessuno potrà avvicinarsi a quel luogo, e il Padre Guardiano raccomanda agli altri frati di non violare il segreto della donna. Atto III Divampa in Italia la lotta tra gli imperiali e gli spagnoli. Don Alvaro, sotto falso nome, milita nelle file dell’esercito franco-spagnolo, nelle vicinanze di Velletri. E’ convinto che donna Leonora sia morta. In battaglia, salva un compatriota: è Don Carlo. Senza riconoscerlo, questi stringe con lui un patto di fratellanza. Gravemente ferito, Don Alvaro gli consegna un plico e lo invita a distruggerlo. Don Carlo si accorge che esso 12 saved. As soon as Alvaro has recovered the two men challenge each other to a duel; but a patrol interrupts them and they must flee. The sun rises on bustling camp activity. THE PLOT Act I The action takes place in Italy and Spain towards the middle of the 18th century. Don Alvaro, who has been rejected by the Marquis of Calatrava as unworthy of marrying his daughter Leonora, tries to abduct the young woman but is discovered by the Marquis. Swearing that Leonora is innocent, Alvaro throws his pistol to the floor and it goes off, killing the Marquis, who dies cursing his daughter. Act IV In the courtyard of the monastery of Hornachuelos five years later, Brother Melitone is dispensing food to the poor. In the monastery there is a new brother, Father Raffaele, who is in reality Don Alvaro. Don Carlo succeeds in tracking him down and challenges him once again to fight to the death. The duel ends with the victory of Don Alvaro, who mortally wounds his opponent. The dying Carlo calls for confession and Alvaro goes to the nearby hermitage, to beg the hermit to give Don Carlo the last rites. Here he recognises Leonora and Alvaro tells her her brother lies dying. She goes to him, but with the last of his strength he stabs her to death. She reappears, supported by Alvaro, and receives the blessing of the Father Superior. Act II Looking for Alvaro, Leonora enters an inn disguised as a man, but does not find him. The gipsy Preziosilla sees through her disguise, but does not betray her. Also Leonora’s brother, Carlo, arrives at the inn: he is looking for the two lovers, having sworn to kill them both. In despair, Leonora takes shelter in the Monastery of Hornachuelos; here brother Melitone takes her to see the Father Superior, to whom she reveals her true identity. The young woman wishes to live as a hermit in a cave not far from the monastery, and the Father Superior warns his brothers that she is to see no one and remain undisturbed. Act III In Italy, during the War of the Austrian Succession. Don Alvaro, under a false name, is a fighter in the Franco-Spanish army, near Velletri. He believes Leonora to be dead. In battle, he rescues a fellow countryman: it is Don Carlo, but he does not recognise him. The two swear eternal friendship and go into battle together. Alvaro is wounded and begs Carlo to burn a packet of documents he will find among his possessions; but Carlo finds in it a portrait of Leonora and thus discovers the true identity of the man he has 13 rettet er einen Landsmann – es ist Don Carlo. Ohne einander zu erkennen, schließen die beiden Männer Freundschaft. Als Alvaro schwer verwundet wird, übergibt er Don Carlo ein Päckchen mit der Aufforderung, es zu vernichten. Don Carlo bemerkt, daß es ein Bildnis seiner Schwester Leonora enthält. Er weiß nun, wer der Mann ist, der ihn gerettet hat. Nachdem der Verwundete genesen ist, fordern die Männer einander zu einem tödlichen Duell heraus. Doch kaum haben sie ihre Degen gezückt, kommt eine Militärstreife vorbei. Um einer Verhaftung zu entgehen, müssen die beiden fliehen. Ein neuer Tag im Feld bricht an. Marketenderinnen und Soldaten machen sich an ihre tägliche Arbeit. DIE HANDLUNG 1. Akt Die Handlung spielt in Spanien und Italien gegen Mitte des 18. Jahrhunderts. Don Alvaro will Donna Leonora, die Tochter des Marquis von Calatrava, entführen, wird aber dabei vom Hausherrn entdeckt, der ihn nicht zum Schwiegersohn wünscht, weil er nicht gleichen Ranges ist wie er. Der Jüngling nimmt die ganze Schuld für die versuchte Entführung auf sich und entlastet das Mädchen völlig. Er wirft die Pistole, die er in Händen hatte, zu Boden, doch löst sich ein Schuß, der den Marquis tötet. Sterbend verflucht dieser seine Tochter. 4. Akt Das Kloster degli Angeli. Im Kreuzgang warten die Armen auf ihre von Fra’ Melitone verteilte Mahlzeit. Unter den Mönchen befindet sich auch der neue Ordensbruder Pater Raffaele, unter welchem Namen sich Alvaro verbirgt. Es gelingt Don Carlo, ihn aufzuspüren und neuerlich zu einem Kampf bis zum letzten Blutstropfen herauszufordern. Um kein Sakrileg zu begehen, tritt Alvaro aus dem Priesterstand aus. Er siegt im Duell und verwundet seinen Gegner tödlich. Dieser ruft nach einem Beichtvater, und um einen solchen zu suchen, nähert sich Alvaro dem Eingang der Einsiedelei, in welcher Leonora lebt. Die beiden erkennen einander, und Alvaro unterrichtet Leonora über die jüngsten tragischen Ereignisse. Leonora eilt zu ihrem Bruder, der bei seinem letzten Atemzug seinen schrecklichen Schwur erfüllt und die Schwester mit dem Degen durchbohrt. Alvaro stützt sie, während ihr der Pater Guardian die letzte Segnung erteilt und dem Paar Trost zuspricht. 2. Akt Leonora ist auf der Suche nach Alvaro. In der Hoffnung, ihn zu finden, verkleidet sie sich als Student und betritt ein Wirtshaus, doch erfüllt sich ihr Wunsch nicht. Die Zigeunerin Preziosilla bemerkt die List, sagt aber nichts, was Leonora verraten könnte. Auch deren Bruder Don Carlo betritt das Wirtshaus. Er ist auf der Suche nach dem Liebespaar und hat geschworen, sie beide zu töten. Leonora sucht verängstigt Zuflucht im Kloster der Madonna degli Angeli. Von Fra’ Melitone empfangen, wird sie zum Pater Guardian geführt. Nur er darf ihre wahre Identität kennenlernen. Die junge Frau zieht sich in eine Einsiedelei in der Nähe des Klosters zurück. Niemand darf sich ihr nähern, und der Pater Guardian ermahnt die anderen Mönche, ihr Geheimnis nicht zu verraten. 3. Akt In Italien lodert der Kampf zwischen den Kaiserlichen und den Spaniern. In der Nähe von Velletri dient Alvaro unter falschem Namen in den Reihen des franko-spanischen Heers. Er glaubt Leonora tot. Im Kampf 14 bataille, il sauve la vie d’un compatriote, Don Carlo, lui aussi sous une fausse identité. Tous deux se jurent une amitié éternelle. Blessé, Don Alvaro remet une lettre à Don Carlo et lui demande de la détruire sans la lire, mais poussé par la curiosité, le jeune homme ouvre la lettre et y découvre le portrait de sa sœur. Il comprend alors qui est l’homme qui lui a sauvé la vie. Dès que le blessé s’est rétabli, il le provoque en duel, mais ils sont interrompus par le retour de la patrouille. Ils doivent s’enfuir pour ne pas être arrêtés. Le jour se lève sur le camp. Vivandières et soldats vaquent à leurs activités quotidiennes. INTRIGUE Acte I En Italie et en Espagne, vers le milieu du XVIIIème siècle. Don Alvaro tente d’enlever Leonora, fille du marquis de Calatrava ; mais il est découvert par le maître de maison qui ne veut pas de lui comme gendre parce qu’il est de rang inférieur. Le jeune homme proteste de l’innocence de la fille du marquis et assume toute la responsabilité de la tentative d’enlèvement. Il lance aux pieds du marquis le pistolet qu’il tenait dans sa main, mais le coup de feu part accidentellement et blesse mortellement le vieil homme, qui maudit sa fille avant de rendre l’âme. Acte IV Le monastère de la Madonna degli Angeli. Dans le cloître, les pauvres attendent leur tour pour recevoir leur soupe quotidienne, que distribue Fra Melitone. Parmi les religieux se cache Don Alvaro sous le nom du Père Raffaele. Don Carlo parvient à le retrouver et le provoque à nouveau en duel. Avant de se battre, Don Raffaele ôte sa soutane pour ne pas commettre de sacrilège ; Don Alvaro blesse mortellement son adversaire, qui demande un confesseur. Don Alvaro part à sa recherche et s’approche de la grotte où s’est retirée Leonora. Tous deux se reconnaissent, et le jeune homme la met au courant des derniers événements. Leonora court au chevet de son frère qui, dans un dernier sursaut, accomplit sa promesse en la poignardant. Alvaro la soutient, tandis que le Père supérieur lui donne l’extrême onction et lui apporte le réconfort des derniers instants. Acte II Leonora est à la recherche d’Alvaro. Espérant le rencontrer, elle se déguise en étudiant et entre dans une auberge, mais elle ne le trouve pas. La gitane Preziosilla s’aperçoit du stratagème, mais ne dit rien qui puisse trahir Leonora. Dans l’auberge se trouve le frère de la jeune fille, Carlo. Il est à la recherche des deux amants et a juré de les tuer tous les deux. En proie à l’angoisse, Leonora se réfugie au Monastère de la Madonna degli Angeli. Accueillie par Fra Melitone, elle est conduite devant le Père supérieur, qui seul connaîtra sa véritable identité. La jeune fille se retire dans une grotte non loin du monastère ; personne ne pourra s’en approcher, et le Père supérieur recommande à tous de ne point violer le secret de la jeune fille. Acte III En Italie, près de Velletri, la lutte entre Italiens et Espagnols s’enflamme. Don Alvaro s’est engagé sous un faux nom dans l’armée franco-espagnole. Il est convaincu que Leonora est morte. Au cours de la 15 Giuseppe Verdi LA FORZA DEL DESTINO Opera in four acts Libretto by Francesco Maria Piave LIBRETTO CD 1 1 CD 1 Ouverture 1 Overture ATTO PRIMO ACT ONE Scena I Siviglia. Una sala tappezzata di damasco con ritratti di famiglia ed arme gentilizie, addobbata nello stile del secolo XVIII, però in cattivo stato. Di fronte, due finestre; quella a sinistra chiusa, l’altra a destra aperta e praticabile, dalla quale si vede un cielo purissimo, illuminato dalla luna, e cime d’alberi. Tra le finestre è un grande armadio chiuso, contenente vesti, biancherie, ecc. Ognuna delle pareti laterali ha due porte. La prima a destra dello spettatore è la comune; la seconda mette alla stanza di Curra. A sinistra in fondo è l’appartamento del Marchese, più presso al proscenio quello di Leonora. A mezza scena, alquanto a sinistra, è un tavolino coperto da tappeto di damasco, e sopra il medesimo una chitarra, vasi di fiori, due candelabri d’argento accesi con paralumi, sola luce che schiarirà la sala. Un seggiolone presso il tavolino; un mobile con sopra un oriuolo fra le due porte a destra; altro mobile sopra il quale è il ritratto tutta figura, del Marchese appoggiato alla parete sinistra. La sala sarà parapettata. Il Marchese di Calatrava, con lume in mano, sta congedandosi da Donna Leonora preoccupata. Curra viene dalla sinistra. First Scene Seville. A large room hung with damask, with family portraits and coats of arms: it is furnished in 18thcentury style, but shabby. Downstage, two windows: that on the left is closed, the other on the right open and practicable, from which can be seen a bright moonlit sky and tree-tops. Between the windows is a large wardrobe, closed, containing clothes, linen, etc. Each of the side walls has two doors: on the spectator’s right, the first is the main one, the second leads to Curra’s room; left, the door backstage leads to the Marquis’s apartment, that nearer the proscenium to Leonora’s. Slightly left of centre is a small table covered with a damask cloth on which lie a guitar, vases of flowers and two shaded silver candelabra, which provide the room’s sole illumination. An armchair near the table; between the right-hand doors a clock standing on a piece of furniture; against the opposite wall another piece of furniture on which is a full-face portrait of the Marquis. Outside the room is a balcony. The Marquis of Calatrava, with a candle in his hand, is bidding goodnight to Donna Leonora, who seems preoccupied; Curra enters from the left. 2 Marchese - abbracciandola con affetto Buona notte, mia figlia. Addio, diletta. Aperto ancora è quel veron. Va a chiuderlo Leonora - fra sé Oh, angoscia! 2 Marquis - embracing Leonora affectionately Goodnight, daughter; goodnight, my dear. Is that balcony window still open? Goes to close it Leonora - aside What anguish! 17 Marchese - Nulla dice il tuo amor? Perché sì triste? Leonora - Padre... signor... Marchese - La pura aura de’ campi pace al tuo cor donava. Fuggisti lo straniero di te indegno. A me lascia la cura dell’avvenir; nel padre tuo confida che t’ama tanto. Leonora - Ah, padre! Marchese - Ebben, che t’ange? Non pianger. Leonora - (Oh, rimorso!) Marchese - Ti lascio. Leonora - gettandosi con effusione tra le braccia del padre Ah, padre mio! Marchese - Ti benedica il cielo. Addio. Leonora - Addio. Il Marchese bacia Leonora e va nelle sue stanze. Marquis - Have you no word of affection? Why are you so sad? Leonora - Father - my Lord Marquis - The pure country air has brought peace to your heart… You have given up that foreigner unworthy of you. Let me take care of the future. Trust your father, who loves you so! Leonora - Ah, father! Marquis - Well, what troubles you? Do not weep. Leonora - (I feel so guilty!) Marquis - I’ll leave you. Leonora - throwing herself effusively into her father’s arms Ah, father! Marquis - Heaven bless you. Goodnight. Leonora - Goodnight! The Marquis kisses her and goes into his room. Scena II Curra segue il Marchese, chiude la porta ond’è uscito, e riviene a Leonora abbandonatasi sul seggiolone piangente Scene II Curra follows the Marquis, closes the door after him and comes back to Leonora, who has given way to tears in the armchair. 3 Curra - Temea restasse qui fino a domani. Si riapra il veron. Tutto s’appronti, e andiamo. Toglie dall’armadio un sacco da notte in cui ripone biancherie e vesti. Leonora - E si amoroso padre, avverso fia tanto ai voti miei? No, no, decidermi non so. Curra - Che dite? Leonora - Quegli accenti nel cor, come pugnali scendevanmi. Se ancor restava, appreso il ver gli avrei... 3 Curra - I was afraid he’d stay here till tomorrow! I’ll open the window again. Let’s get everything ready, and go. She takes from the wardrobe an overnight bag which has been filled with linen and clothes. Leonora - Could so loving a father be so opposed to my wishes? No, no, I can’t make up my mind. Curra - What are you saying? Leonora - Those words pierced my heart like daggers. Had he stayed longer, I should have confessed the truth. 18 Curra - smettendo il lavoro Domani allor nel sangue suo saria Don Alvaro, od a Siviglia prigioniero, e forse al patibol poi! Leonora - Taci. Curra - E tutto questo perché ei volle amar chi non l’amava. Leonora - Io non amarlo? Tu ben sai s’io l’ami... Patria, famiglia, padre per lui non abbandono? Ahi, troppo, troppo sventurata sono! 4 Me, pellegrina ed orfana, lungi dal patrio nido. un fato inesorabile sospinge a stranio lido. Colmo di triste immagini, da’ suoi rimorsi affranto è il cor di questa misera dannato a eterno pianto, ecc. Ti lascio, ahimè, con lacrime, dolce mia terra, addio. Ahimè, non avrà termine per mi sì gran dolore! Addio. 5 Curra - M’aiuti, signorina, più presto andrem. Leonora - S’ei non venisse? Guarda l’orologiov È tardi. Mezzanotte è suonata! Contenta Ah no, più non verrà! Curra - Qual rumore? Calpestio di cavalli! Leonora - corre al verone È desso! Curra - Era impossibil ch’ei non venisse! Leonora - Oh Dio! Curra - Bando al timore. Curra - stopping work Then tomorrow Don Alvaro would lie in his own blood, or in prison in Seville, perhaps with the scaffold to follow. Leonora - Hush! Curra - And all this because he loved someone who didn’t love him. Leonora - I not love him? You well know if I love him... Am I not leaving for him my country, my family, my father? Ah, my misfortunes are too great! 4 An orphan and a wanderer, an inexorable fate drives me on towards an alien shore far from my native soil. Filled with gloomy fancies, broken by remorse, the heart of this unhappy being is condemned to endless weeping. I leave thee, alas, in tears, sweet homeland! Farewell. Alas! there will be no end to such great sorrow! Farewell. 5 Curra - Help me, madam, then we can be away more quickly. Leonora - And if he doesn’t come? She looks at the clock. It’s late. It’s past midnight. Relieved, happy Ah no, he will not come now! Curra - What’s that noise? The clatter of horses’ hooves! Leonora - running to the balcony It is he! Curra - He could not have failed to come! Leonora - Heaven! Curra - Away with fear! 19 Scena III Detti. Don Alvaro senza mantello, con giustacuore a maniche larghe, e sopra una giubbetta da Majo, rete sul capo, stivali, speroni, entra dal verone e si getta tra le braccia di Leonora. Scene III The above. Don Alvaro, booted and spurred but without a cloak, in a wide-sleeved jerkin with a smart jacket over it, enters from the balcony and throws himself into Leonora’s arms. Alvaro - Ah, per sempre, o mio bell’angiol, ne congiunge il cielo adesso! L’universo in questo amplesso Io mi veggo giubilar. Leonora - Don Alvaro! Alvaro - Ciel, che t’agita? Leonora - Presso è il giorno. Alvaro - Da lung’ora mille inciampi tua dimora m’han vietato penetrar; ma d’amor sì puro e santo nulla opporsi può all’incanto, e Dio stesso il nostro palpito in letizia tramutò. a Curra Quelle vesti dal verone getta. Leonora - a Curra Arresta. Alvaro - a Curra No, no... a Leonora Seguimi, lascia omai la tua prigione. Leonora - Ciel, risolvermi non so. Alvaro - Pronti destrieri di già ne attendono, un sacerdote ne aspetta all’ara. Vieni, d’amore in sen ripara che Dio dal cielo benedirà! E quando il sole, nume dell’India, di mia regale stirpe signore, il mondo inondi del suo splendore, sposi, o diletta, ne troverà. Leonora - È tarda l’ora. Alvaro - a Curra Su, via, t’affretta. Leonora - a Curra Ancor sospendi. Alvaro - Ah! now, my beautiful angel, heaven has united us forever! In this embrace I see the whole universe rejoicing. Leonora - Don Alvaro! Alvaro - Heavens! Why are you agitated? Leonora - It is almost daybreak. Alvaro - A thousand obstacles have long prevented me from entering your house; but nothing can resist the spell of a love so pure and holy, and God himself has transformed our anxiety into joy. to Curra Throw those clothes down from the balcony. Leonora - to Curra Stop! Alvaro - to Curra No, no... to Leonora Follow me. Leave your prison, now. Leonora - Oh heaven! I cannot bring myself to it. Alvaro - Swift steeds are ready for us below; a priest awaits us at the altar. Come, shelter in the bosom of a love that God will bless from heaven! And when the sun, god of the Indies, lord of my royal race, bathes the earth in his splendour, he will find us married, beloved. Leonora - The hour is late. Alvaro - to Curra Come along, hurry! Leonora - to Curra Wait a moment. 20 Alvaro - Eleonora! Leonora - Diman... Alvaro - Che parli? Leonora - Ten prego, aspetta. Alvaro - Diman! Leonora - Domani si partirà. Anco una volta il padre mio, povero padre, veder desio; e tu contento, gli è ver, ne sei? Sì, perché m’ami, né opporti dei. Anch’io, tu il sai, t’amo io tanto! Ne son felice, oh cielo, quanto! Gonfio di gioia ho il cor! Restiamo... Sì mio Alvaro, io t’amo, io t’amo! Piange Alvaro - Gonfio di gioia hai il core, e lagrimi! Come un sepolcro tua mano è gelida! Tutto comprendo, tutto, signora! Leonora - Alvaro! Alvaro! Alvaro - Eleonora! Io sol saprò soffrire. Tolga Iddio che i passi miei per debolezza segua. Sciolgo i tuoi giuri. Le nuziali tede sarebbero per noi segnal di morte se tu, com’io, non m’ami, se pentita... Leonora - Son tua, son tua col core e colla vita! Seguirti, fino agli ultimi confini della terra; Con te sfidar, impavida di rio destin, la guerra, mi fia perenne gaudio d’eterea voluttà. Ti seguo. Andiam, dividerci il fato non potrà. Alvaro - Sospiro, luce ed anima di questo cor che t’ama. Finché mi batte un palpito Alvaro - Eleonora! Leonora - Tomorrow... Alvaro - What are you saying? Leonora - I beg you, wait. Alvaro - Tomorrow! Leonora - Tomorrow we will go. Once more I want to see my father, my poor father, and you will agree, won’t you? Yes, because you love me and would not deny me… I too, you know it… I love you so! That makes me happy! Oh heaven, so happy! My heart is filled with joy! Let us stay… Yes, Alvaro, I love you! I love you! Tears choke her. Alvaro - Your heart is filled with joy, and yet you weep! Your hand is cold as the tomb! I understand everything now, my lady! Leonora - Alvaro! Alvaro! Alvaro - Eleonora! I shall learn to suffer alone. God forbid that through weakness you should follow me. I release you from your oath. To marry would mean death for us if you do not love me as I love you, if you regret... Leonora - I am yours, with my heart and being! To follow you to the furthest ends of the earth, fearlessly with you to defy the assault of evil fate, let these for me be an endless joy of heavenly delight! I will follow you - let us go. Fate cannot keep us apart. Alvaro - I breathe again, light and soul of this heart which loves you; so long as a breath of life is in me, 21 far paga ogni tua brama il solo ed immutabile desio per me sarà. Mi segui. Andiam, dividerci il fato non potrà. S’avvicinano al verone, quando ad un tratto si sente a sinistra un aprire e chiuder di porte. Leonora - Qual rumor! Curra - ascoltando Ascendono le scale! Alvaro e Leonora Mi segui / Ti seguo. Andiam. Dividerci il fato non potrà. 6 Leonora - È tardi. Alvaro - Allor di calma è d’uopo. Curra - Vergin santa! Leonora - a Don Alvaro Colà t’ascondi. Alvaro - traendo una pistola No. Difenderti degg’io. Leonora - Ripon quell’arma. Contro al genitore Vorresti? . . . Alvaro - No, contro me stesso! Leonora - Orrore! my sole, unchanging desire shall be to fulfil your every wish. Follow me - let us go. Fate cannot keep us apart. From the left is heard the sound of a door being opened and closed. Leonora - What is that noise? Curra - listening They’re coming up the stairs! Alvaro and Leonora Follow me/I will follow you. Let us go. No, fate cannot keep us apart. 6 Leonora - It is too late! Alvaro - Then we must keep calm. Curra - Holy Virgin! Leonora - to Don Alvaro Hide in there. Alvaro - drawing a pistol No, I must protect you. Leonora - Put away that gun. Would you raise it against my father? Alvaro - No, against myself. Leonora - Horror! Scena IV Dopo vari colpi, apresi con istrepito la porta, ed il Marchese di Calatrava entra infuriato, brandendo una spada e seguito da due servi con lumi. Scene IV After several blows, the door is noisily thrown open. The Marquis of Calatrava enters in a rage, brandishing a sword; he is followed by two servants carrying lamps. Marchese - Vil seduttor! Infame figlia! Leonora - correndo a suoi piedi No, padre mio. Marchese - Io più nol sono. Alvaro - Il solo colpevole son io. presentandogli il petto Ferite, vendicatevi. Marchese - No, la condotta vostra Da troppo abbietta origine Uscito vi dimostra. Marquis - Vile seducer! Shameless daughter! Leonora - throwing herself at his feet No, father. Marquis - No longer am I your father! Alvaro - I alone am the guilty one. baring his chest Strike - take your revenge! Marquis - No, your conduct shows the baseness of your origins. 22 Alvaro - risentito Signor Marchese! Marchese - a Leonora Scostati. ai servi S’arresti l’empio. Alvaro - cavando nuovamente la pistola Guai se alcun di voi si muove. Leonora - correndo a lui Alvaro, oh ciel, che fai? Alvaro - al Marchese Cedo a voi sol, ferite. Marchese - Morir per mano mia! Per mano del carnefice tal vita spenta sia! Alvaro - Signor di Calatrava! Pura siccome gli angeli è vostra figlia, il giuro. Reo sono io solo. Il dubbio che l’ardir mio qui desta si tolga colla vita. Eccomi inerme. Getta via la pistola che, cadendo al suolo scarica il colpo, e ferisce mortalmente il Marchese. Marchese - Io muoio! Alvaro - disperato Arma funesta! Leonora - correndo al padre Aita! Marchese - a Leonora Lungi da me. Contamina tua vista la mia morte! Leonora - Padre! Marchese - Ti maledico! Cade tra le braccia dei servi Leonora - Cielo, pietade! Alvaro - Oh, sorte! I servi portano via il Marchese, mentre Don Alvaro trae seco verso il verone la sventurata Leonora. Alvaro - offended My lord! Marquis - to his daughter Stand aside. to the servants Arrest the scoundrel! Alvaro - again taking out the pistol Beware, if either of you moves... Leonora - running to him Alvaro - heavens, what are you doing? Alvaro - to the Marquis I yield to you alone. Strike! Marquis - Die by my hand? Let such a life be ended by that of the executioner! Alvaro - My Lord of Calatrava! Pure as the angels is your daughter - I swear it. I alone am guilty. Let the suspicion aroused by my boldness be removed along with my life. Here I stand, unarmed… He throws down the pistol; as it strikes the ground, it goes off, mortally wounding the Marquis. Marquis - I am dying! Alvaro - desperately Fatal weapon! Leonora - running to her father’s side Help! Marquis - to Leonora Get away from me! The sight of you sullies my death. Leonora - Father! Marquis - I curse you! He falls into the arms of his servants. Leonora - Heaven, have mercy! Alvaro - Oh, cruel destiny! The servants carry the Marquis to his apartments while Don Alvaro drags the unfortunate Leonora with him towards the balcony. 23 ATTO SECONDO ACT TWO Scena I Villaggio d’Hornachuelos e vicinanze. Grande cucina d’un osteria a pian terreno. A sinistra la porta d’ingresso che dà sulla via; di fronte una finestra ed un credenzone con piatti, ecc. A destra in fondo un gran focolare ardente con varie pentole; più vicino alla boccascena breve scaletta che mette ad una stanza la cui porta è praticabile. Da un lato, gran tavola apparecchiata con sopra una lucerna accesa. L’oste e l’ostessa, che non parlano, sono affaccendati ad ammanire la cena. L’Alcade è seduto presso al foco; Don Carlo, vestito da studente, è presso la tavola. Alquanti mulattieri fra i quali Mastro Trabuco, ch’è al dinanzi sopra un suo basto. Due contadini, due contadine, la serva ed un mulattiere ballano la Seguidilla. Sopra altra tavola, vino, bicchieri, fiaschi, una bottiglia d’acquavite. L’Alcade, uno studente, Mastro Trabuco, Mulattieri, Paesani, Famigli, Paesane, ecc. Scene I The village of Hornachuelos and its surroundings. The large ground-floor kitchen of an inn. Left, the street door; downstage a window and a sideboard with dishes, etc. Upstage right, a large fireplace with various pots on the fire; nearer the proscenium a short staircase leading to a room with a practicable door. On one side a large table is laid, with a lighted lamp on it. The innkeeper and his wife (who do not speak) are busy preparing supper. The Alcalde is sitting near the fire, a student (Don Carlos in disguise) near the table. Some muleteers, among them Mastro Trabuco, in front on one of his pack-saddles. Two pairs of villagers, the servingwench and a muleteer are dancing a seguidilla. On another table are wine, glasses, flasks, a bottle of brandy. Peasants, families, etc. 7 Coro - Holà, holà, holà! Ben giungi, o mulattier, la notte a riposar. Holà, holà, holà! Qui devi col bicchier le forze ritemprar. L’ostessa mette sulla tavola una grande zuppiera Alcade - sedendosi alla mensa La cena è pronta. Coro - prendendo posto presso la tavola A cena, a cena. Carlo - fra sé Ricerco invan la suora e il seduttore. Perfidi! 7 Chorus - Holà, holà, holà! Muleteers, you’ve done well to come here to rest for the night. Holà, holà, holà! Here you must renew your strength with a glass! The hostess sets a great tureen on the table. Alcalde - seating himself at the table Supper’s ready. Chorus - taking their places at the table Let’s eat. Carlos - to himself In vain I seek my sister and her seducer dishonourable wretches! 24 Coro - all’Alcade Voi la mensa benedite. Alcade - Può farlo il licenziato. Carlo - Di buon grado. In nomine Patris, et Filii, et Spiritus Sancti. Coro - sedendo Amen. Leonora - presentandosi alla porta vestita da uomo Che vedo! Mio fratello! Si ritira. L’ostessa avrà già distribuito il riso e siede con essi. Trabuco è in disparte, sempre appoggiato al suo basto. Alcade - assaggiando Buono. Carlo - mangiando Eccellente. Mulattieri - Par che dica, “Mangiami”. Carlo - all’ostessa Tu das epulis accumbere Divum. Alcade - Non sa il Latino, ma cucina bene. Carlo - Viva l’ostessa! Tutti - Evviva! Carlo - Non vien, Mastro Trabuco? Trabuco - È venerdì. Carlo - Digiuna? Trabuco - Appunto. Carlo - E quella personcina con lei giunta? Chorus - to the Alcalde You say Grace. Alcalde - The learned scholar can say it. Carlos - Willingly. In nomine Patris, et Filii, et Spiritus Sancti. Chorus - seating themselves Amen. Leonora - appearing, dressed as a man What do I see! My brother! She withdraws. The hostess has already served out the rice and sat down with the others. Trabuco is still apart, resting on his saddle. Alcalde - tasting It’s good. Carlos - eating Excellent. Muleteers - It just asks to be eaten. Carlos - to the hostess Tu das epulis accumbere Divam. Alcalde - She knows no Latin, but she cooks well. Carlos - Three cheers for the hostess! All - Hurrah! Carlos - Aren’t you coming, Master Trabuco? Trabuco - It’s Friday. Carlos - Are you fasting? Trabuco - That’s right. Carlos - And that little person who came with you? Scena II Detti e Preziosilla che entra saltellando Scene II The above and Preziosilla, skipping in Preziosilla - Viva la guerra! Tutti - Preziosilla! Brava, brava! Carlo e Coro - Qui, presso a me . . . Tutti - Tu la ventura dirne potrai. Preziosilla - Chi brama far fortuna? Tutti - Tutti il vogliamo. Preziosilla - Correte allor soldati in Italia, dov’è rotta la guerra Preziosilla - Hurrah for the war! All - Preziosilla! Brava! Carlos and Chorus - Here, sit next to me. All - You can tell our fortunes. Preziosilla - Who wants to make his fortune? All - We all do! Preziosilla - Then go as soldiers to Italy, where war has broken out 25 contro il Tedesco. Tutti - Morte ai Tedeschi! Preziosilla - Flagel d’Italia eterno, e de figlioli suoi. Tutti - Tutti v’andremo. Preziosilla - Ed io sarò con voi. Tutti - Viva! 8 Preziosilla - Al suon del tamburo, al brio del corsiero, al nugolo azzurro del bronzo guerrier; dei campi al sussurro s’esalta il pensiero! È bella la guerra, è bella la guerra! Evviva la guerra, evviva! Tutti - È bella la guerra, evviva la guerra! Preziosilla - È solo obliato da vile chi muore. Al bravo soldato, al vero valor è premio serbato di gloria, d’onor! È bella la guerra! Evviva la guerra! ecc. Tutti - È bella la guerra! Evviva la guerra! ecc. Preziosilla - volgendosi all’uno e all’altro Se vieni, fratello, sarai caporale; e tu colonnello, e tu generale. Il dio furfantello dall’arco immortale farà di cappello al bravo uffiziale. È bella la guerra, evviva la guerra! Tutti - È bella la guerra, evviva la guerra! Carlo - presentandole la mano against the Germans. All - Death to the Germans! Preziosilla - The eternal scourge of Italy and of her sons. All - We’ll all go. Preziosilla - And I with you. All - Hurrah! 8 Preziosilla - At the sound of the drum, at the mettle of the steed, at the blue cloud of the warlike cannon, at the bustle of the camp, the spirits rise. How splendid is war! Hurrah for war! All - How splendid is war! Hurrah for war! Preziosilla - He alone is forgotten who dies a coward. For the brave soldier, for true valour is reserved the reward of glory and honour. How splendid is war! Hurrah for war! All - How splendid is war! Hurrah for war! Preziosilla - turning from one to another If you come, brother, you’ll be a corporal, and you a colonel, and you a general. The little roguish god of the immortal bow will salute the brave officer. How splendid is war! Hurrah for war! All - Hurrah for war! Carlos - showing his palm to Preziosilla 26 E che riserbasi allo studente? Preziosilla - guardando la mano Ah, tu miserrime vicende avrai. Carlo - Che di’? Preziosilla - fissandolo Non mente il labbro mai. poi, sottovoce Ma a te, carissimo, non presto fé. Non sei studente, non dirò niente, ma, gnaffe, a me non se la fa, tra la la la! And what’s in store for the student? Preziosilla - reading his hand Oh, you will have most wretched experiences. Carlos - What are you saying? Preziosilla - gazing at him My lips never lie. whispering But, dear lad, I don’t believe you. You’re no student. I’ll say nothing, but no one takes me in no, ‘pon my word, tra la la la! Scena III Detti e Pellegrini che passano da fuori Scene III The above. A band of pilgrims passes by outside. 9 Coro di Pellegrini - fuori Padre Eterno Signor, pietà di noi, Tutti - alzandosi e scoprendosi la testa Chi sono? Alcade - Son pellegrini che vanno al giubileo. Leonora - ricomparendo agitatissima sulla porta Fuggir potessi! Don Carlo, Mulattieri Che passino attendiamo. Alcade - Preghiam con lor. Tutti - Preghiamo. Lasciano la mensa e s’inginocchiano Coro di Pellegrini - Divin Figlio Signor, pietà di noi. Tutti - Su noi prostrati e supplici stendi la man, Signore; Coro di Pellegrini - Santo Spirito Signor, pietà di noi. 9 Chorus of Pilgrims - in the distance Eternal Father, Lord, have mercy on us. All - rising and taking off their hats Who are they? Alcalde - Pilgrims on their way to the celebration. Leonora - reappearing in great agitation at the same door If only I could escape! Carlos, Muleteers Let’s wait till they’ve gone by. Alcalde - Let us pray with them. All - Let us pray. All leave the table and kneel. Chorus of Pilgrims - Divine Son, Lord, have mercy on us. All - Over us, prostrate and supplicant, extend Thy hand, O Lord; Chorus of Pilgrims - Holy Ghost, Lord, have mercy on us. 27 Uno e Trino Signor, pietà di noi. Tutti - Dall’infernal malore ne salvi tua bontà. Signor, pietà! Leonora - fra sé Ah, dal fratello salvami che anela il sangue mio. Se tu nol vuoi, gran Dio, nessun mi salverà! Signor, pietà! Leonora rientra nella stanza chiudendone la porta. Tutti riprendono i loro posti. Si passano un fiasco. 10 Carlo - Viva la buona compagnia! Tutti - Viva! Carlo - alzando il bicchiere Salute qui, l’eterna gloria poi. Tutti - facendo altrettanto Così sia. Carlo - Già cogli angeli, Trabuco? Trabuco - E che? Con quest’inferno! Carlo - E quella personcina con lei giunta, venne pel giubileo? Trabuco - Nol so. Carlo - Per altro, è gallo oppur gallina? Trabuco - De’ viaggiator non bado che al danaro. Carlo - Molto prudente! poi all’Alcade Ed ella che giungere la vide, perché a cena non vien? Alcade - L’ignoro. Carlo - Dissero chiedesse acqua ed aceto. Ah, ah! Per rinfrescarsi. Alcade - Sarà. Carlo - È ver che è gentile e senza barba? Alcade - Non so nulla. Carlo - fra sé Parlar non vuol! God One and Three, Lord, have mercy on us. All - May Thy goodness save us from infernal perdition. O Lord, have mercy! Leonora - to herself Ah, save me from a brother who thirsts for my blood. If Thou wilt not, great God, no one can save me! O Lord, have mercy! Leonora goes back into the room, closing the door. All resume their places. A flask is passed round. 10 Carlos - Here’s to our good company! All - Hurrah! Carlos - lifting his glass Health here, eternal glory later! All - doing likewise Hear, hear! Carlos - Are you already with the angels, Trabuco? Trabuco - What? In this hell-hole? Carlos - And did that little thing with you come for the celebration? Trabuco - I don’t know. Carlos - By the way is it a cock or a hen? Trabuco - A traveller’s money is all I notice. Carlos - Very prudent of you. turning to the Alcalde You saw him arrive. Why didn’t he come to supper? Alcalde - I don’t know. Carlos - It’s said he asked for vinegar and water ha, ha! to refresh himself. Alcalde - It may be. Carlos - It’s true that he’s delicate and beardless? Alcalde - I know nothing. Carlos - to himself He won’t talk. 28 a Trabuco Ancora lei. Stava sul mulo seduta o a cavalcioni? Trabuco - impazientito Che noia! Carlo - Onde veniva? Trabuco - So che andrò presto o tardi in Paradiso. Carlo - Perché? Trabuco - Ella il Purgatorio mi fa soffrire. Carlo - Or dove va? Trabuco - In istalla a dormir colle mie mule, che non san di latino, né sono baccellieri. Prende il suo basto e parte. to Trabuco I turn to you again. Did he ride the mule side-saddle or astride? Trabuco - impatiently This is a bore! Carlos - Where did he come from? Trabuco - I know sooner or later I’ll go to heaven! Carlos - Why? Trabuco - Because you’re making me suffer purgatory. Carlos - Where are you going now? Trabuco - To the stable, to sleep with my mules, who know no Latin and aren’t Bachelors of Arts. He takes up his saddle and leaves. Scena IV I Suddetti meno Mastro Trabuco Scene IV The above, except for Master Trabuco Tutti - Ah, ah! È fuggito! 11 Carlo - Poiché imberbe l’incognito, facciamgli col nero due baffetti; doman ne rideremo. Tutti - Bravo! Bravo! Alcade - Protegger debbo i viaggiator; m’oppongo. Meglio farebbe dirne d’onde venga, ove vada, e chi ella sia. Carlo - Lo vuoi saper? Ecco l’istoria mia. Son Pereda, son ricco d’onore, Baccelliere mi fe’ Salamanca. Sarò presto in utroque dottore, che di studio ancor poco mi manca. Di là Vargas mi tolse da un anno, ed a Siviglia con sé mi guidò. Non trattenne Pereda alcun danno, per l’amico il suo core parlò. Della suora un amante straniero colà il padre gli avea trucidato, ed il figlio, da pro’ cavaliero, All - Ha, ha - he’s fled! 11 Carlos - Since the stranger is beardless, let’s paint him a moustache with lamp-black. Tomorrow we’ll have a good laugh at it. All - Bravo! Bravo! Alcalde - I have to protect all travellers; I’m against this. It would be better if you told us where you come from, where you’re going and who you are. Carlos - Do you want to know? Here’s my story. I am Pereda, rich in honours; Salamanca made me a Bachelor. Soon I shall be a full-fledged Doctor, for I’ve only a few studies to complete. Vargas took me from there a year ago and brought me with him to Seville. Pereda would brook no affront; his heart spoke out for his friend. A foreigner, his sister’s lover, had murdered his father there, and the son, like the brave knight he is, 29 la vendetta ne aveva giurato. Gl’inseguimmo di Cadice in riva, né la coppia fatal si trovò. Per l’amico Pereda soffriva, che per esso il suo core parlò. Là e dovunque narrar che del pari la sedotta col vecchio perìa, che a una zuffa tra servi a sicari solo il vil seduttore sfuggìa. Io da Vargas allor mi staccava, ei seguir l’assassino giurò. Verso America il mare solcava, e ai suoi studi Pereda tornò! Tutti - Truce storia Pereda narrava! Generoso il suo core mostrò. 12 Alcade - Sta bene. Preziosilla - Ucciso fu quel Marchese? Carlo - Ebben? … Preziosilla - L’assassino rapìa sua figlia? Carlo - Sì. Preziosilla - E voi, l’amico fido, cortese, andaste a Cadice e pria a Siviglia? Ah, gnaffe, a me non se la fa, tra la la la! L’Alcade si alza e guarda l’oriuolo Alcade - Figliuoli, è tardi; poiché abbiam cenato, si rendan grazie a Dio, e partiamo. Preziosilla, Carlo e Coro - Partiam, partiamo. Buona notte, buona notte. Tutti - Holà! Holà! È l’ora di riposar. Allegri, o mulattier! Holà! Carlo - Son Pereda, son ricco d’onore, ecc. Alcade - Sta ben. Preziosilla - Ah, tra la la la! Ma, gnaffe, a me no se la fa. Tutti - Buon notte. Andiam, andiam. had sworn to be revenged on him. We followed them to the coast at Cadiz, but could not find the guilty pair. Pereda suffered for his friend, and his heart spoke out for him. There and everywhere alike, it was said that the ruined girl had perished with her father, and that in a scuffle between the servants and the assassins, only the vile seducer escaped. I then separated from Vargas, who swore to pursue the murderer. He set sail for America, and Pereda returned to his studies. All - Pereda has told a grim story, and shown his generosity of heart! 12 Alcalde - Very good. Preziosilla - This Marquis was killed? Carlos - Well? Preziosilla - And the assassin ravished his daughter? Carlos - Yes. Preziosilla - And you, the faithful, noble friend, went to Cadiz and before that to Seville? No one takes me in, no, ‘pon my word, tra la la la! The Alcalde rises and looks at the clock Alcalde - My sons, it’s late; let us give thanks to God for our meal and be off. Preziosilla, Carlos and Chorus - Let’s be off. Good night, good night. All - Holà, holà! It’s time to rest. Look lively, muleteers! Carlos - I am Pereda, rich in honours; etc. Alcalde - Very well, yes, very well. Preziosilla - Ha ha, tra la la la. No one takes me in, ’upon my word! All - Good night. Let’s go! 30 Scena V Una piccola spianata sul declivio di scoscesa montagna. A destra precipizi e rupi; di fronte la facciata della chiesa della Madonna degli Angeli; a sinistra la porta del Convento, in mezzo alla quale una finestrella; da un lato la corda del campanello. Sopra vi è una piccola tettoia sporgente. Al di là della chiesa alti monti col villaggio d’Hornachuelos. La porta della chiesta è chiusa, ma larga, sopra dessa una finestra semicircolare lascerà vedere la luce interna. A mezza scena, un po’ a sinistra, sopra quattro gradini s’erge una rozza croce di pietra corrosa dal tempo. La scena sarà illuminata da luna chiarissima. Donna Leonora giunge ascendendo dalla destra, stanca, vestita da uomo, con pastrano a larghe maniche, largo cappello e stivali. Leonora. Scene V A small level clearing on the slope of a steep mountain. Cliffs and precipices on the right; centre, the façade of the church of Our Lady of the Angels; left, the door of the monastery, in the middle of which is a small grille, and beside which is a bell rope. Above is a small projecting shelter. Beyond the church, high mountains, with the village of Hornachuelos. The church door is closed, but lights can be seen through a large semi-circular window above it. Slightly to the left of centre a rough stone cross, worn by time, stands at the top of four steps. Bright moonlight illuminates the scene. Donna Leonora enters exhausted, climbing in from the right. She is dressed as a man, in a wide-sleeved cloak, broad-brimmed hat and riding boots. Leonora. 13 Leonora - Sono giunta! Grazie, o Dio! Estremo asil questo è per me! Son giunta! Io tremo! La mia orrenda storia è nota in quell’albergo, e mio fratel narrolla! Se scoperta m’avesse! Cielo! Ei disse naviga vers’ occaso. Don Alvaro! Né morto cadde quella notte in cui io, io del sangue di mio padre intrisa, l’ho seguito e il perdei! Ed or mi lascia, mi fugge! Ohimè, non reggo a tanta ambascia. Cade in ginocchio 14 Madre, pietosa Vergine, perdona al mio peccato. M’aita quel ingrato dal core a cancellar. In queste solitudini espierò l’errore. Pietà di me, Signore. 13 Leonora - I’m here at last! Thanks be to Thee, O God! This is my last refuge! I am here! I am trembling! My dreadful story is known at the inn - my own brother was telling it! If he had discovered me! Heavens! He said that Don Alvaro was sailing to the West! He did not fall dead that night when I, soaked in my father’s blood, followed him, but lost him! And now he leaves me, he flees from me! Ah, I cannot bear such anguish! She falls to her knees. 14 Mother, merciful Virgin, forgive my sin. Help me to erase that ingrate from my heart. In this seclusion I will expiate my guilt. Have mercy on me, Lord; 31 Deh, non m’abbandonar! L’organo accompagna il canto mattutino dei frati Ah, quei sublimi cantici, si alza dell’organo i concenti, che come incenso ascendono a Dio sui firmamenti, inspirano a quest’alma fede, conforto e calma! Coro dei Frati - interno Venite, adoremus et procedamus ante Deum, Ploremus, ploremus coram Domino, coram Domino qui fecit nos. Leonora - S’avvia Al santo asilo accorrasi. E l’oserò a quest’ora? Alcun potria sorprendermi! O misera Leonora, tremi? Il pio frate accoglierti no, non ricuserà. Non mi lasciar, soccorrimi, pietà Signor, pietà! Deh, non m’abbandonar! Frati - Ploremus, ploremus coram Domino qui fecit nos. Leonora va a suonare il campanello del convento. do not forsake me. The organ accompanying the monks’ morning prayers is heard. Ah, those sublime hymns rising and organ harmonies rising like incense to God in Heaven inspire my soul with faith, comfort and peace! Chorus of Monks - within Venite, adoremus et procedamus ante Deum. Ploremus, ploremus coram Domino, coram Domino, qui fecit nos. Leonora - She moves forward. Let me hasten to the holy refuge. Dare I at this hour? Someone might surprise me. Oh wretched Leonora, do you tremble? The pious monk will not refuse to shelter you. Do not forsake me, help me, have mercy, Lord! Do not abandon me, O Lord; Chorus of Monks - Ploremus coram Domino, qui fecit nos. Leonora rings the monastery bell. Scena VI Si apre la finestrella della porta e n’esce la luce d’una lanterna che riverbera sul volto di Donna Leonora la quale si arretra, spaventata. Fra Melitone parla sempre dall’interno Scene VI The wicket window opens; a lantern shines out, lighting up the face of Donna Leonora, who steps back in fright. Fra Melitone speaks to her from within. 15 Melitone - Chi siete? Leonora - Chiedo il Superiore. Melitone - S’apre alle cinque la chiesa, Se al giubileo venite. Leonora - Il Superiore, per carità, Melitone - Che carità a quest’ora! Leonora - Mi manda il Padre Cleto. Melitone - Quel santo uomo? Il motivo? 15 Melitone - Who are you! Leonora - I wish to speak to the Superior. Melitone - The church opens at five o’clock, if you have come for the celebration. Leonora - The Superior, for mercy’s sake! Melitone - What mercy at this hour? Leonora - Father Cleto sent me. Melitone - That saintly man? For what reason? 32 Leonora - Urgente. Melitone - Perché mai? Leonora - Un infelice... Melitone - Brutta solfa... Però v’apro ond’entriate. Leonora - Nol posso. Melitone - No? Scomunicato siete? Che strano fia aspettare a ciel sereno. V’annuncio, e se non torno, buona notte. Chiude la finestrella. Leonora - An urgent one. Melitone - Whatever is it? Leonora - An unfortunate soul… Melitone - A sad refrain… But I’ll open for you to come in. Leonora - I cannot. Melitone - No? Are you excommunicated? How strange to wait out in the open! I’ll announce you. If I don’t come back, then goodnight. He closes the window. Scena VII Donna Leonora sola Scene VII Leonora, alone Leonora - Ah, s’ei mi respingesse! Fama pietoso il dice. Ei mi proteggerà. Vergin m’assisti. Leonora - What if he should reject me! He is said to be merciful. He will protect me. Holy Virgin, help me. Scena VIII Donna Leonora, il Padre Guardiano e Fra Melitone Scene VIII The Father Superior comes to the door with Melitone. 16 Guardiano - Chi mi cerca? Leonora - Son io. Guardiano - Dite. Leonora - Un segreto... Guardiano - Andate, Melitone. Melitone - partendo, fra sé Sempre segreti! E questi santi soli han da saperli! Noi siamo tanti cavoli. Guardiano - Fratello, mormorate? Melitone - Ohibò, dico ch’é pesante la porta e fa rumore. Guardiano - Obbedite. Melitone - fra sé Che tuon da Superiore! Rientra nel convento socchiudendone la porta. 16 Father Superior - Who is asking for me? Leonora - I am. Father Superior - Speak. Leonora - It is a secret. Father Superior - Leave us, Melitone. Melitone - as he goes, to himself Always secrets! And only these holy men must know them! We’re so many cabbages! Father Superior - Brother, what are you muttering? Melitone - Oh, I was saying that the door is heavy and makes a noise. Father Superior - Obey me! Melitone - muttering to himself He’s asserting his authority! He goes back inside, leaving the door ajar. 33 Scena IX Scene IX Guardiano - Or siam soli. Leonora - Una donna son io. Guardiano - Una donna a quest’ora! Gran Dio! Leonora - Infelice, delusa, rejetta, dalla terra e del ciel maledetta, che nel pianto prostratavi al piede, di sottrarla all’inferno vi chiede. Guardiano - Come un povero frate lo può? Leonora - Padre Cleto un suo foglio v’inviò? Guardiano - Ei vi manda? Leonora - Sì. Guardiano - sorpreso Dunque voi siete Leonora di Vargas! Leonora - Fremete! Guardiano - No, venite fidente alla croce. Là del cielo v’ispiri la voce. Leonora s’inginocchia presso la croce, la bacia, quindi torna al Padre Guardiano. 17 Leonora - Più tranquilla, l’alma sento dacché premo questa terra. De’ fantasmi lo spavento più non sorge a farmi guerra… Più non sorge sanguinante di mio padre l’alma innante, né terribile l’ascolto la sua figlia maledir. Guardiano - Sempre indarno qui rivolto fu di Satana l’ardir. Leonora - Perciò tomba qui desio fra le rupi ov’altra visse. Guardiano - Che! Sapete? Leonora - Cleto il disse. Guardiano - E volete… Leonora - Darmi a Dio. Guardiano - Guai per chi si lascia illudere Father Superior - Now we are alone … Leonora - I am a woman. Father Superior - A woman at this hour! Good Lord! Leonora - One unhappy, deceived, rejected, accursed by both earth and heaven, who throws herself in tears at your feet and begs you to rescue her from hell. Father Superior - How can a poor monk do that? Leonora - Did Father Cleto not send you a note? Father Superior - He sent you? Leonora - Yes. Father Superior - surprised Then you are Leonora de Vargas! Leonora - You shudder! Father Superior - No. Come, trusting, to the Cross. There may the voice of heaven inspire you. Leonora kneels at the foot of the Cross and kisses it; then she turns to the Father Superior. 17 Leonora - I feel my soul calmer since I trod this ground. I no longer feel the terror of phantoms assailing me … No longer does my father’s shade rise bleeding before me, nor do I hear him fearfully curse his daughter. Father Superior - Satan’s presumption has always been powerless here. Leonora - That is why I seek my tomb here among the rocks, where another woman lived. Father Superior - What! You know of her? Leonora - Cleto told me. Father Superior - And you wish…? Leonora - To give myself to God. Father Superior - Woe to him who lets himself 34 Dal delirio d’un momento! Più fatal per voi sì giovane giungerebbe il pentimento. Leonora - Ah, tranquilla l’alma sento, ecc. Guardiano - Guai per chi si lascia illudere. Guai! Chi può leggere il futuro? Chi immutabil farvi il core? E l’amante? Leonora - Involontario m’uccise il genitor. Guardiano - E il fratello? Leonora - La mia morte di sua mano egli giurò. Guardiano - Meglio a voi le sante porte schiuda un chiostro. Leonora - Un chiostro? No! 18 Se voi scacciate questa pentita Andrò per balze, gridando aita, ricovro ai monti, cibo alle selve. E fin le belve ne avran pietà. Ah, sì, del cielo qui udii la voce: “Salvati all’ombra di questa croce.” Voi mi scacciate? È questo il porto. Chi tal conforto mi toglierà? Guardiano - A te sia gloria, o Dio clemente, padre dei miseri onnipossente. A cui sgabello sono le sfere! Il tuo volere si compirà! È fermo il voto? Leonora - È fermo. Guardiano - V’accolga dunque Iddio. Leonora - Bontà divina! Guardiano - Sol io saprò chi siate. Tra le rupi è uno speco; ivi starete. Presso una fonte, al settimo dì, scarso cibo porrovvi io stesso. Leonora - V’andiamo. be misled by the delirium of a moment! Regret would prove fatal for one so young as you. Leonora - I feel my soul calmer, etc. Father Superior - Woe to him who lets himself be misled. Who can read into the future? Who can tell your heart won’t change? And your lover? Leonora - He killed my father by accident. Father Superior - And your brother? Leonora - He has sworn that I shall die by his hand. Father Superior - Better that a convent should open its holy doors to you. Leonora - A convent? No. 18 If you drive this penitent away I shall wander through the rocks crying for help, begging refuge from the mountains, food from the woods, until the beasts take pity and end my woe. Ah yes, here have I heard the voice of heaven: ”Take refuge in the shadow of this Cross.” And you drive me away’? This is my haven. Who shall take this solace from me? Father Superior - Glory to Thee, O merciful God, Omnipotent Father of the wretched, the spheres are whose footstool! Thy will be done! Your decision is firm? Leonora - It is. Father Superior - May God receive you then! Leonora - Divine compassion! Father Superior - Only I shall know who you are. Among the rocks is a cave: there you will stay. Near a spring, each seventh day, I myself will set down a frugal meal. Leonora - Let us go there. 35 Guardiano - verso la porta Melitone? a Melitone che comparisce Tutti i fratelli con ardenti ceri, dov’ è l’ara maggiore, nel tempio si raccolgan del Signore. Melitone rientra Sull’alba il piede all’eremo solinga volgerete; ma pria dal pane angelico conforto all’alma avrete. Le sante lane a cingere ite, e sia forte il cor. Sul nuovo calle a reggervi v’assisterà il Signor. Entra nel Convento, e ne ritorna subito portando un abito da Francescano che presenta a Leonora. Leonora - Tua grazia, o Dio, sorride alla rejetta! O, gaudio insolito! Io son ribenedetta! Già sento in me rinascere a nuova vita il cor; Plaudite, o cori angelici, mi perdonò il Signor. Entrano nella stanza del portinaio. Father Superior - calling towards the door Melitone! to Melitone, as he appears Let all the brothers, with lighted candles, assemble at the high altar in the temple of the Lord. Melitone goes in again. At dawn, you will make your way alone to the hermitage; but first you shall have heavenly comfort from the holy bread. Go, put on your holy robe, and may your heart be firm. The Lord will help you set forth on your new path. He enters the monastery and returns, carrying a Franciscan habit which he gives to Leonora. Leonora - O God, thy grace smiles upon the outcast! Oh, unaccustomed joy! I am blessed once more! I feel my heart within me reborn to new life … Sing praises, o angelic chorus, for the Lord has pardoned me. They enter the porter’s lodge. CD 2 CD 2 1 Scena X La gran porta della chiesa si apre. Di fronte vedesi l’altar maggiore illuminato. L’organo suona. Dai lati del coro procedono due lunghe file di Frati, con ceri ardenti. Più tardi il Padre Guardiano precede Leonora, in abito da frate, che s’inginocchia al pié dell’altare e riceve da lui la Comunione. Egli la conduce fuor della chiesa, i Frati gli si schierano 1 Scene X The great door of the church opens, revealing the high altar illuminated. The organ is playing. Two long files of monks proceed down the sides of the choir, carrying lighted tapers. After them comes the Father Superior, followed by Leonora in monk’s habit: she kneels at the altar and receives Holy Communion. He leads her out of the church; the 36 intorno. Leonora si prostra innanzi a lui che, stendendo solennemente le mani sopra il suo capo, intuona: monks gather round them. Leonora kneels before him and he raises his hands solemnly above her head, saying 2 Guardiano - Il santo nome di Dio Signore Sia benedetto. Coro - Sia benedetto. Guardiano - Un’alma a piangere viene l’errore, tra queste balze chiede ricetto. Il santo speco noi le schiudiamo. V’è noto il loco? Coro - Lo conosciamo. Guardiano - A quell’asilo, sacro, inviolato, nessun si appressi. Coro - Obbediremo. Guardiano - Il cinto umile non sia varcato che nel divide. Coro - Nol varcheremo. Guardiano - A chi il divieto frangere osasse, o di quest’alma scoprir tentasse nome o mistero: maledizione! Coro - Maledizione! Maledizione! Il cielo fulmini, incenerisca, l’empio mortale se tanto ardisca. Su lui scatenisi ogni elemento, l’immonda cenere ne sperda il vento. Guardiano - a Leonora Alzatevi e partite. Alcun vivente più non vedrete. Dello speco il bronzo ne avverta se periglio vi sovrasti, 2 Father Superior - Blessed be the holy name of the Lord God. Melitone and Monks - May it be blessed. Father Superior - A soul has come to weep for its sin and seeks sanctuary amid these mountains. For this soul, we are opening the sacred cave. You know the place? Melitone and Monks - We know it. Father Superior - Let no one approach that holy, inviolate refuge. Melitone and Monks -We will obey. Father Superior - Nor shall the humble enclosure be crossed that separates us from it. Melitone and Monks - We will not cross it. Father Superior - On him who would dare to break this ban or try to learn the name or secret of this soul, a curse shall fall! All - A curse! A curse! Let heaven hurl its thunderbolts and consume the impious mortal who would so dare. Let all the elements be loosed upon him, let his vile ashes be scattered to the winds. Father Superior - to Leonora Rise and depart. Henceforth you will see no living soul. The bell of the cave will warn us if danger threatens you, 37 o per voi giunto sia l’estremo giorno... A confortarvi l’alma volerem pria che a Dio faccia ritorno. Tutti - La Vergine degli Angeli vi copra del suo manto, e voi protegga vigile di Dio l’Angelo santo. Leonora - La Vergine degli Angeli mi copra del suo manto. e mi protegga vigile di Dio l’Angelo santo. Leonora bacia la mano del Padre Guardiano, e s’avvia all’eremo, sola. Il Guardiano si ferma sulla porta e stendendo le braccia verso la parte ov’è scomparsa Leonora, la benedice. or if your last hour has come. Then we shall hasten to comfort your soul before it returns to God. All - May Our Lady of the Angels cover you in Her mantle, and the Holy Angel of God keep vigil to protect you. Leonora - May Our Lady of the Angels cover me in Her mantle, and the Holy Angel of God keep vigil to protect me. Leonora kisses the Father Superior’s hand, rises, and sets off alone for the hermitage. The Father Superior stretches out his arms towards her, blessing her. ATTO TERZO ACT THREE Scena I In Italia presso Velletri. Bosco. Notte oscurissima. Don Alvaro, in uniforme di capitano spagnuolo dei Granatieri del Re, si avanza lentamente dal fondo. Si sentono voci interne a destra. First Scene Italy, near Velletri. A wood on a pitch-dark night. Don Alvaro is in the uniform of a Spanish captain in the Royal Grenadiers. Voices are heard off-stage to the right. 3 Coro - Attenti al gioco, attenti, attenti al gioco... Prima Voce - Un asso a destra. Seconda Voce - Ho vinto. Prima Voce - Un tre alla destra. Cinque a manca. Seconda Voce - Perdo. Alvaro - La vita è inferno all’infelice. Invano morte desio! Siviglia! Leonora! Oh, rimembranza! Oh, notte ch’ogni ben mi rapisti! Sarò infelice eternamente, è scritto. 3 Soldiers - Keep your eyes on the game. First Soldier - An ace on the right. Second Soldier - I’ve won! First Soldier - A three on the right. A five on the left. Second Soldier - I’ve lost! Alvaro - Life is a hell to the unfortunate. In vain do I long for death. Seville! Leonora! Oh, memories! Oh, night that robbed me of all joy! I shall be unhappy forever - so it is written. 38 Della natal sua terra il padre volle spezzar l’estranio giogo, e coll’unirsi all’ultima dell’Incas la corona cingere confidò. Fu vana impresa. In un carcere nacqui; m’educava il deserto; sol vivo perché ignota è mia regale stirpe! I miei parenti sognarono un trono, e li destò la scure! Oh, quando fine avran le mie sventure! 4 O tu che in seno agli angeli eternamente pura, salisti bella, incolume falla mortal jattura, non iscordar di volgere lo sguardo a me tapino, che senza nome ed esule, in odio del destino, chiedo anelando, ahi misero, la morte d’incontrar. Leonora mia, soccorrimi, Pietà del mio penar! Pietà di me! 5 Carlo - dall’interno Al tradimento! Voci - Muoia! Alvaro - Quali grida! Carlo - Aita! Alvaro - Si soccorra. Voci - Muoia! Muoia! Accorre al luogo onde si udivano le grida; si sente un picchiare di spade, alcuni ufficiali attraversando la scena fuggendo in disordine da destra a sinistra. My father wished to shatter the foreign yoke on his native land, and by uniting himself with the last of the Incas, thought to assume the crown. The attempt was in vain! I was born in prison, educated in the desert; I live only because my royal birth is known to none! My parents dreamed of a throne; the axe awakened them! Oh, when will my misfortunes end? 4 Oh, you who have ascended, forever pure, to the bosom of the angels, lovely and untouched by mortal sorrow, do not forget to look down on me, unhappy wretch, who, nameless and exiled, the prey of fate, longingly seeks to encounter death, unfortunate that I am! Leonora, help me, have pity on my anguish. Help me, have pity on me! 5 Carlos - in the distance Treachery! Voices - Let him die! Alvaro - What is that shouting? Carlos - Help! Alvaro - I must help. Voices - Kill him! Don Alvaro runs off towards where the cries came from: the clash of swords is heard. Some officers cross the scene from right to left, fleeing in disorder. Don Alvaro returns with Don Carlos. 39 Scena II Don Alvaro ritorna con Don Carlo Scene II Don Alvaro and Don Carlos Alvaro - Fuggir! Ferito siete? Carlo - No, vi debbo la vita. Alvaro - Chi erano? Carlo - Assassini. Alvaro - Presso al campo così? Carlo - Franco dirò: fu alterco al gioco. Alvaro - Comprendo, colà, a destra. Carlo - Sì. Alvaro - Ma come, si nobile d’aspetto, a quella bisca scendeste? Carlo - Nuovo sono. Con ordini del general sol ieri giunsi; senza voi morto sarei. Or dite a chi debbo la vita? Alvaro - Al caso … Carlo - Pria il mio nome dirò. (Non sappia il vero!) Don Felice de Bornos, aiutante del duce. Alvaro - Io, Capitan dei Granatieri, Don Federico Herreros. Carlo - La gloria dell’esercito! Alvaro - Signore... Carlo - Io l’amistà ne ambia; la chiedo e spero. Alvaro - Io pure della vostra sarò fiero. Si danno la destra. 6 Alvaro e Carlo - Amici in vita e in morte il mondo ne vedrà. Uniti in vita e in morte entrambi troverà. Voci interne - Andiamo, all’armi! Carlo - Con voi scendere al campo d’onor, emularne l’esempio saprò. Alvaro - Testimone del vostro valor, ammirarne le prove saprò. Alvaro - They’ve escaped. Are you wounded? Carlos - No. I owe my life to you. Alvaro - Who were they? Carlos - Assassins. Alvaro - So near camp? Carlos - I will be frank: it was a quarrel over cards. Alvaro - I see - over there to the right? Carlos - Yes. Alvaro - But how did you, so noble of bearing, become involved in that den of thieves? Carlos - I’m new here. I arrived with orders from the general only yesterday; without you I should now be dead. Tell me, to whom do I owe my life? Alvaro - To chance... Carlos - First tell you my name. (He must not know the truth!) Don Felix de Bornos, aide to the commander. Alvaro - I am Don Federico Herreros, captain of Grenadiers. Carlos - The pride of the army! Alvaro - Sir... Carlos - I desire your friendship; I ask and hope for it. Alvaro - And I shall be proud to have yours! They shake hands. 6 Alvaro and Carlos - Friends in life and death the world shall see us. United in life and death it shall find us both. Soldiers - To arms! Carlos - Going to the field of honour with you, I can emulate your example. Alvaro - As witness of your courage, I shall be able to admire its proof. 40 Coro - All’armi! Escono correndo. Soldiers - To arms! They rush off. Scena III È il mattino. Salotto nell’abitazione d’un ufficiale superiore dell’esercito spagnuolo in Italia non lungi da Velletri. Nel fondo sonvi due porte, quella a sinistra mette ad una stanza da letto, l’altra è la comune. A sinistra presso il proscenio è una finestra. Si sente il rumore della vicina battaglia. Un Chirurgo militare ed alcuni Soldati ordinanze dalla comune corrono alla finestra. Scene III It is morning. The quarters of a senior officer of the Spanish army, in Italy, not far from Velletri. At the rear are two doors, that on the left leading to a bedroom, the other being the main door. A window on the left near the proscenium. The sounds of the nearby battle can be heard. An army surgeon and some orderlies enter through the main door and run to the window. Soldati - Arde la mischia. Chirurgo - guardando con un cannocchiale Prodi i granatieri! Soldati - Li guida Herreros. Chirurgo - Ciel! … Ferito ei cadde! … Piegano i suoi! … L’aiutante li raccozza, alla carica li guida! … Già fuggono i nemici. I nostri han vinto! Voci - di fuori A Spagna gloria! Altre Voci - Viva l’Italia! Tutti - È nostra la vittoria! Chirurgo - Portan qui ferito il Capitano. Orderlies - The battle is fierce! Surgeon - looking through his telescope The grenadiers are valiant! Orderlies - Herreros is leading them. Surgeon - My God, he has fallen wounded! His men are giving way! His aide is rallying them, leading them in a charge! The enemy is on the run now. Our men have won! Soldiers - within Glory to Spain! Others - Long live Italy! All - Victory! Surgeon - They’re bringing the Captain here, wounded. Scena IV Don Alvaro, ferito e svenuto, è portato in una lettiga da quattro Granatieri. Da un lato è il Chirurgo, dall’altro è Don Carlo, coperto di polvere ed assai afflitto. Un Soldato depone una valigia sopra un tavolino. La lettiga è collocata quasi nel mezzo della scena. 7 Carlo - Piano… qui posi… Approntisi il mio letto. Scene IV Don Alvaro, wounded and unconscious, is brought in on a stretcher by four grenadiers. On one side of him the surgeon, on the other Don Carlos, covered with dust and very distressed. A soldier sets a dispatch-case down on a small table. The stretcher is laid down almost in the centre of the scene. 7 Carlos - Gently... put him here... Prepare my bed for him. 41 Chirurgo - Silenzio. Carlo - V’ha periglio? Chirurgo - La palla che ha nel petto mi spaventa. Carlo - Deh, il salvate. Alvaro - rinvenendo Ove son? Carlo - Presso l’amico. Alvaro - Lasciatemi morire. Carlo - Vi salveran le nostre cure. Premio l’Ordine vi sarà di Calatrava. Alvaro - Di Calatrava! Mai! Mai! Carlo - fra sé Che! Inorridì di Calatrava al nome! Alvaro - Amico … Chirurgo - Se parlate … Alvaro - Un detto sol … Carlo - al chirurgo Ven prego ne lasciate. Il chirurgo si ritira. Don Alvaro accenna a Don Carlo di appressarglisi. 8 Alvaro - Solenne in quest’ora giurarmi dovete far pago un mio voto. Carlo - Lo giuro. Alvaro - Sul core cercate. Carlo - Una chiave. Alvaro - indicando la valigia Con essa trarrete un piego celato! L’affido all’onore, colà v’ha un mistero che meco morrà. S’abbruci me spento. Carlo - Lo giuro, sarà. Alvaro - Or muoio tranquillo. Vi stringo al cor mio. Surgeon - Quiet! Carlos - Is he in danger? Surgeon - The bullet in his chest causes me concern. Carlos - Oh, save him! Alvaro - gaining consciousness Where am I? Carlos - With your friend. Alvaro - Let me die. Carlos - Our treatment will save you. You will be awarded the Order of Calatrava. Alvaro - Of Calatrava! Never! Never! Carlos - to himself What! He shuddered at the name of Calatrava! Alvaro - My friend… Surgeon - If you talk… Alvaro - One word only. Carlos - to the surgeon Be good enough to leave us. The surgeon withdraws to the background. Don Alvaro beckons to Don Carlos to come nearer. 8 Alvaro - You must swear to me, in this solemn hour, to carry out a wish of mine. Carlos - I swear. Alvaro - Look above my heart. Carlos - A key! Alvaro - pointing to the case With it you will take out A hidden packet. I entrust it to your honour. Within is a secret which must die with me. Burn it when I am dead. Carlos - It shall be done, I swear. Alvaro - Now I can die in peace. I press you to my heart. 42 Carlo - lo abbraccia con grande emozione Amico, fidate nel cielo! Addio. Alvaro - Addio. Il chirurgo ed i soldati trasportano il ferito nella stanza da letto. Carlos - embracing him with great emotion My friend, trust in heaven. Farewell. Alvaro - Farewell. The surgeon and orderlies carry the wounded man into the bedroom. Scena V Scene V 9 Carlo - Morir! Tremenda cosa! Sì intrepido, sì prode, ei pur morrà! Uom singolar costui! Tremò di Calatrava al nome. A lui palese n’ è forse il disonor? Cielo! Qual lampo! S’ei fosse il seduttore? Desso in mia mano, e vive! Se m’ingannassi? Questa chiave il dica. Apre convulso la valigia, e ne trae un plico suggellato Ecco i fogli! Che tento! S’arresta E la fé che giurai? E questa vita che debbo al suo valor? Anch’io lo salvo! S’ei fosse quell’ Indo maledetto che macchiò il sangue mio? Il suggello si franga. Niun qui mi vede. No? Ben mi vegg’io! Getta il plico 10 Urna fatale del mio destino, va, t’allontana, mi tenti invano. L’onor a tergere qui venni, e insano d’un onta nuova nol macchierò. Un giuro è sacro per l’uom d’onore, que’ fogli serbino il lor mistero. Disperso vada il mal pensiero che all’atto indegno mi concitò. E s’altra prova rinvenir potessi? 9 Carlos - To die! A terrible thing so fearless, so valiant, yet he must die! A strange man, this! He shuddered at the name of Calatrava! Has he perhaps heard of our dishonour? Heavens! A sudden thought! What if he were the seducer? And in my hands - alive! But if I am wrong? This key will tell me! In agitation he opens the case and takes out a sealed envelope. Here are the papers! What am I doing? about to open it, stops And the oath I swore? And my life that I owe to his bravery? But I saved him, too! And what if he were the cursed Indian , who soiled my blood? I will break the seal, no one can see me here. No? But I can see myself. He throws down the envelope 10 Away with you, fatal urn of my destiny; you tempt me in vain. I came here to redeem my honour, and in madness will not stain it with this new shame. An oath is sacred to a man of honour; these papers shall keep their secret. Perish the evil thought that spurred me to the unworthy deed. But if I could find some other proof? 43 Vediam. Torna a frugare nella valigia Qui v’ha un ritratto... Suggel non v’é… nulla ei ne disse… Nulla promisi… s’apra dunque… Ciel! Leonora! Don Alvaro è il ferito! Ora egli viva, e di mia man poi muoia! Il chirurgo si presenta sulla porta della stanza Chirurgo - Lieta novella, è salvo! Esce. Carlo - È salvo! Oh gioia! Egli è salvo! Gioia immensa che m’inondi il cor ti sento! Potrò alfine il tradimento sull’infame vendicar. Leonora, ove t’ascondi? Di’: seguisti tra le squadre chi del sangue di tuo padre ti fe’ il volto rosseggiar? Ah, felice appien sarei se potessi il brando mio ambedue d’averno al dio d’un sol colpo consacrar! Parte precipitosamente. Let’s see. He again rummages in the case Here is a portrait. It has no seal. He said nothing about this. I promised nothing. Let me open it then. Heavens! Leonora! The wounded man is Don Alvaro! Now let him live, and then die by my hand! The surgeon appears at the door of the room Surgeon - Good news; he’s saved. He goes in again. Carlos - He is saved! Oh joy! He is saved! What immense joy I feel flooding my heart! At last I can avenge the betrayal on the vile wretch! Leonora, where are you hiding? Tell me, have you followed into this camp the man who reddened your face with your father’s blood? Ah, I should be overjoyed if this sword of mine with a single stroke could send them both forever down to the Prince of Darkness! He goes out quickly. CD 3 CD 3 Scena VI Accampamento militare presso Velletri. Sul davanti a sinistra è una bottega da rigattiere; a destra un’altra ove si vendono cibi, bevande e frutta. All’ingiro sono tende militari, baracche di rivenduglioli, ecc. È notte; la scena è deserta. Una pattuglia entra cautamente in scena, esplorando il campo. 1 Coro - Compagni, sostiamo, il campo esploriamo. Scene VI A military encampment near Velletri. In the foreground, left, a pedlar’s booth; on the right another where food, drink and fruit are sold. All around, military tents, hucksters’ huts, etc. It is night, and the scene is deserted. A patrol enters cautiously, exploring the camp. 1 Chorus - Comrades, let’s halt and explore the camp; 44 Non s’ode rumor, non brilla un chiarore; in sonno profondo sepolto ognun sta. Compagni, inoltriamo, il campo esploriamo, fra poco la sveglia suonare s’udrà. not a sound is heard, not a glimmer of light shines; everyone is buried in profound sleep. Companions, let’s halt and explore the camp; soon reveille will be sounded. Scena VII Spunta l’alba lentamente. Entra Don Alvaro pensoso Scene VII Dawn is slowly breaking. Don Alvaro, deep in thought. 2 Alvaro - Né gustare m’ è dato un’ ora di quiete. Affranta è l’alma dalla lotta crudel. Pace ed oblio indarno io chieggo al cielo. 2 Alvaro - It is not given to me to enjoy one hour of peace. My soul is wracked by the cruel strife. Peace and oblivion do I ask in vain of heaven. Scena VIII Detto e Don Carlo Scene VIII The above and Don Carlos Carlo - Capitano . . . Alvaro - Chi mi chiama? Riconosce Carlo Voi, che si larghe cure mi prodigaste. Carlo - La ferita vostra sanata è appieno? Alvaro - Sì. Carlo - Forte? Alvaro - Quale prima. Carlo - Sosterreste un duel? Alvaro - Con chi? Carlo - Nemici non avete? Alvaro - Tutti ne abbiam… ma a stento comprendo… Carlo - No? Messaggio non v’inviava Don Alvaro, l’Indiano? Alvaro - Oh tradimento! 3 Sleale! Il segreto fu dunque violato? Carlos - Captain … Alvaro - Who calls me? recognizing Don Carlos You who lavished such great care on me? Carlos - Is your wound fully healed? Alvaro - Yes. Carlos - Are you strong? Alvaro - As before. Carlos - Could you fight a duel? Alvaro - With whom? Carlos - Have you no enemies? Alvaro - We all have… but I hardly understand… Carlos - No? Did Don Alvaro the Indian send you no message? Alvaro - Oh, treachery! 3 Faithless man! So the secret was violated? 45 Carlo - Fu illeso quel piego, l’effigie ha parlato. Don Carlos di Vargas, tremate io sono. Alvaro - D’ardite minacce non m’agito al suono. Carlo - Usciamo all’istante. Un deve morire. Alvaro - La morte disprezzo, ma duolmi inveire contr’uom che per primo amistade m’offria. Carlo - No, no, profanato tal nome non sia. Alvaro - Non io, fu il destino, che il padre v’ha ucciso. Non io che sedussi quell’angiol d’amore. Ne guardano entrambi, e dal paradiso Ch’io sono innocente vi dicono al core. Carlo - Adunque colei? Alvaro - La notte fatale io caddi per doppia ferita mortale. Guaritone, un anno in traccia ne andai, ahimè, ch’era spenta Leonora trovai. Carlo - Menzogna, menzogna! La suora - Ospitavala antica parente. Vi giunsi, ma tardi… Alvaro - Ed ella? Carlo - Fuggente. Alvaro - trasalendo E vive! Ella vive, gran Dio! Carlo - Sì, vive. Carlos - That packet remained unread; the portrait gave it away. Tremble, for I am Don Carlos de Vargas. Alvaro - I am not perturbed by the sound of violent threats. Carlos - Come out at once: one of us must die… Alvaro - I scorn death, but it grieves me to revile one who at first offered me friendship. Carlos - No, no, let that name not be profaned. Alvaro - It was not I, but destiny that killed your father. Nor did I seduce that angel of love. They both look down on us, and from heaven they tell you in your heart that I am innocent. Carlos - And she? Alvaro - That fatal night I fell, with two grievous wounds. When I recovered, I searched for a year… Alas, I found that Leonora was no more! Carlos - You lie, you lie! An old relative gave my sister shelter; I went to her, but it was too late… Alvaro - And she?… Carlos - Had fled. Alvaro - springing up And is alive! She lives, great God!! Carlos - Yes, she lives. 46 Alvaro - Don Carlo, amico, il fremito ch’ogni mia fibra scuote, vi dica che quest’ anima infame esser non puote. Vive! Gran Dio, quell’angelo… Carlo - Ma in breve morirà. Ella vive, ma in breve morirà. Alvaro - No, d’un imene il vincolo stringa fra noi la speme; e s’ella vive, insieme cerchiamo ove fuggì. Giuro che illustre origine eguale a voi mi rende, e che il mio stemma splende come rifulge il dì. Carlo - Stolto! Fra noi dischiudesi insanguinato avello. Come chiamar fratello chi tutto a me rapì? D’eccelsa o vile origine. è d’uopo ch’io vi spegna, e dopo voi l’indegna che il sangue suo tradì. Alvaro - Che dite? Carlo - Ella morrà. Alvaro - Tacete! Carlo - Il giuro a Dio: morrà l’infame. Alvaro - Voi pria cadrete nel fatal certame. Carlo - Morte! Ov’io non cada esanime Leonora giungerò. Tinto ancor del vostro sangue questo acciar le immergerò. Alvaro - Morte! Sì! Col brando mio un sicario ucciderò. Il pensier volgete a Dio. L’ora vostra alfin suonò. Alvaro - Don Carlos, my friend, let the tremor that shakes my every fibre tell you that my soul is incapable of baseness. She lives! Great God, that angel! Carlos - But soon she shall die. She lives, but soon shall die. Alvaro - No, let the hope of Hymen’s bond draw us together; and if she is alive, let us together seek where she has fled to. I swear that a noble origin makes me your equal, and that my escutcheon shines as brightly as the day. Carlos - Fool! Between us there gapes a bloody sepulchre. How can I call brother one who has robbed me of everything? Whether your origin is noble or base, I have to kill you, and after you the worthless creature who betrayed her own flesh and blood. Alvaro - What are you saying? Carlos - She shall die. Alvaro - Do not say that! Carlos - I swear it before God: the infamous creature shall die. Alvaro - You shall fall first in mortal combat. Carlos - Death! Before I fall lifeless I will reach Leonora and plunge into her this blade, still reddened with your blood. Alvaro - Death, yes!… With my sword I will kill a murderer. Turn your thoughts to God. Your hour has struck at last. 47 Tutti e due - A morte! Andiam! Sguainano le spade e si battono furiosamente. Both - Let us go! To death we go … to death! They draw their swords and fight furiously. Scena IX Accorre la pattuglia del campo a separarli Scene IX The camp patrol rushes up to separate them Coro - Fermi! Arrestate! Carlo - furente No - la sua vita o la mia - tosto. Coro - Lunge di qua si tragga. Alvaro - fra sé Forse del ciel l’aita a me soccorre. Carlo - Colui morrà! Coro - a Carlo che cerca svincolarsi Vieni! Carlo - a Don Alvaro Carnefice del padre mio! Alvaro - Or che mi resta? Pietoso Iddio, tu ispira, illumina il mio pensier. Al chiostro, all’eremo, ai santi altari l’oblio, la pace chiegga il guerrier. Chorus - Stop! Hold hard! Carlos - furiously No. His life or mine… at once. Chorus - Lead them away from here. Alvaro - to himself Perhaps heaven is lending me aid. Carlos - He shall die! Chorus - to Don Carlos, who is attempting to free himself Come! Carlos - to Don Alvaro My father’s murderer! Alvaro - Now what is left me? Merciful God, inspire and enlighten my thoughts. Let the warrior seek peace and oblivion in the cloister, in the hermitage, at the holy altars. Scena X Spunta il sole; il rullo dei tamburi e lo squillo delle trombe danno il segnale della sveglia. La scena va animandosi a poco a poco. Soldati spagnuoli ed italiani di tutte le armi sortono dalle tende ripulendo schioppi, spade, uniformi, ecc. Ragazzi militari giuocano ai dai sui tamburi. Vivandiere che vendono liquori, frutta, pane, ecc. girano per il campo. Preziosilla, dall’alto d’una bracca, predice la buona ventura. Scena animatissima. Scene X The sun rises. A roll of drums and a blare of trumpets give the signal for reveille. The scene gradually becomes more animated. Spanish and Italian soldiers of all branches of the army come out of their tents, cleaning rifles, swords, uniforms, etc. Military cadets play at dice on the drums. Vivandières sell drinks, fruit, bread, etc. From the top of a booth, Preziosilla is telling fortunes. An extremely lively scene. 4 Coro - Lorché pifferi e tamburi par che assordino la terra, siam felici, ch’è la guerra gioia e vita al militar. Vita gaia, avventurosa, cui non cal doman né ieri, 4 Chorus - When fifes and drums seem to deafen the earth we are happy, for to the soldier war is life and joy. A gay, adventurous life for one who cares not for tomorrow 48 ch’ama tutti i suoi pensieri sol nell’oggi concentrar. Preziosilla - alle donne Venite all’indovina, ch’è giunta di lontano, e puote a voi l’arcano futuro decifrar. ai soldati Correte a lei d’intorno, la mano le porgete, le amanti apprenderete se fide vi restâr. Coro - Andate/Andiamo all’indovina, la mano le porgiamo/porgete, le belle udir possiamo se fide a voi restâr. Preziosilla - Chi vuole il paradiso s’accenda di valore, e il barbaro invasore s’accinga a debellar. Avanti, avanti, avanti, predirvi sentirete qual premio coglierete dal vostro battagliar. Soldati - Avanti, avanti, avanti, predirci sentiremo qual premio coglieremo dal nostro battagliar. Vivandiere - Avanti, avanti, avanti, predirvi sentirete qual premio coglierete dal vostro battagliar. Coro - circondandola Avanti, avanti, avanti. 5 Soldati - Qua, vivandiere, un sorso. Le vivandiere versano loro Un Soldato - Alla salute nostra! or yesterday, and loves to concentrate his thoughts only on today. Preziosilla - to the women Come to the fortune-teller, who has come from afar, and can interpret for you the mysterious future. to the soldiers Come, gather round her, show her your hands! You will learn if your sweethearts are remaining true to you. Chorus - Go to the fortune-teller, give her your hands; you will learn if your fair ones are remaining true to you. Preziosilla - He who longs for paradise must burn with valour and prepare to drive out the barbarous invader. Come, come, come, you shall hear me predict what prize you will win from your fighting. Soldiers - Come on, come on, come on, we will hear her predict what prize we shall win from our fighting. Vivandières - Go on, go on, go on, you shall hear her predict what prize you will win from your fighting. Chorus - Surrounding her Come on! 5 Soldiers - Here, girls, a drink! The vivandières pour them drinks First Soldier - Here’s to us! 49 Tutti - bevendo Viva! All - drinking Good health! Scena XI L’attenzione è attirata da Mastro Trabuco, rivendugliolo, che, dalla bottega a sinistra, viene con una cassetta al collo portante vari oggetti di meschino valore. Scene XI Attention is drawn to Trabuco, the pedlar, who comes out of the stall on the left with a tray of cheap merchandise slung from his neck. Trabuco - A buon mercato chi vuol comprare? Forbici, spille, sapon perfetto! Io vendo e compro qualunque oggetto, concludo a pronti qualunque affar. Un Soldato - Ho qui un monile; quanto mi dai? Un Altro Soldato - V’è una collana. Se vuoi la vendo. Un Altro Soldato - Questi orecchini, li pagherai? Tutti - mostrando orologi, anelli, ecc. Vogliamo vendere… Trabuco - Ma quanto vedo tutto è robaccia, brutta robaccia! Tutti - Tale, o furfante, è la tua faccia. Trabuco - Pure aggiustiamoci, per ogni pezzo do trenta soldi. Tutti - Da ladro è il prezzo. Trabuco - Ih! Quanta furia! C’intenderemo. Qualch’altro soldo v’aggiungeremo. Date qua, subito! Tutti - Purché all’istante venga il denaro bello e sonante. Trabuco - Prima la merce, qua, colle buone. Tutti - dandogli gli oggetti A te. Trabuco - ritirando la roba e pagando A te, a te, benone. Tutti - cacciandolo Sì, sì, ma vattene! Trabuco - fra sé, contento Trabuco - Who wants to buy cheap? Scissors, pins, beautiful soap. I buy and sell anything at all and strike a deal straight away. Second Soldier - I’ve a bracelet; what’ll you give me for it? Third Soldier - Here’s a necklace. I’ll sell it if you like. First Soldier - What’ll you pay for these earrings? Soldiers - showing watches, rings, etc. We want to sell... Trabuco - But as far as I can see it’s all trash, worthless trash! Soldiers - Just like your face, you rogue. Trabuco - Still, let’s agree; thirty soldi for each article. Soldiers - That’s plain robbery! Trabuco - Hey, what a rage! Let’s come to terms. We’ll add a few more soldi. Give me the things, quick! Soldiers - On condition the money’s forthcoming, shiny and ringing. Trabuco - First the goods, here, one at a time. Soldiers - handing him the objects Here you are. Trabuco - taking the things and paying Here you are - good! Soldiers - driving him away Yes, but now be off with you! Trabuco - to himself, happily 50 Che buon affare! A buon mercato chi vuol comprare? Si avvia verso un’altro lato del campo. That was good business! going off to the other side of the camp Who wants to buy cheap? Scena XII Detti e Contadini questuanti con ragazzi a mano. Scene XII The above and a group of begging peasants enter, holding their sons by the hand 6 Contadini - Pane, pan per carità! Tetti e campi devastati n’ha la guerra, ed affamati cerchiam pane per pietà. 6 Peasants - Bread, bread, for pity’s sake! The war has destroyed our homes and fields. We are starving and beg for bread, for mercy’s sake! Scena XIII Detti ed alcune Reclute piangenti che giungono scortate. Scene XIII Some conscripts enter under escort, weeping. Reclute - Povere madri deserte nel pianto per dura forza dovemmo lasciar. Della beltà n’han rapiti all’incanto, a’ nostre case vogliamo tornar. Vivandiere - accostandosi gaiamente alle reclute ed offrendo loro da bere Non piangete, giovanotti, per le madri, per le belle. V’ameremo quai sorelle, vi sapremo consolar. Certo il diavolo non siamo. Quelle lagrime tergete, al passato, ben vedete, ora è inutile pensar. Preziosilla - entra fra le reclute, ne prende alcune pel braccio, e dice loro burlescamente: Che vergogna! Su, coraggio! Bei figliuoli, siete pazzi? Se piangete quai ragazzi vi farete corbellar. Conscripts - By brute force we were made to leave our poor mothers, deserted and in tears. We’ve been torn away from all we love; we want to go back home. Vivandières - gaily approaching the conscripts and offering them drinks Don’t cry, lads, for your mothers and sweethearts. We will love you like sisters, and know how to console you. Certainly we’re not devils. So dry your tears; you can see it’s no use to think about the past. Preziosilla - Entering among the conscripts, she takes a couple by the arm and says to them: Shame on you! Come, be brave! Handsome lads, are you mad? If you cry like babies, you’ll be laughed at. 51 Un’occhiata a voi d’intorno, e scommetto che indovino, ci sarà più d’un visino che sapravvi consolar. Su, coraggio, coraggio, coraggio! 7 Tutti - Nella guerra è la follia che dee il campo rallegrar. Viva, viva la pazzia Che qui sola ha da regnar! Le vivandiere prendono le reclute pel braccio e s’incomincia vivacissima danza generale. Ben presto la confusione e lo schiamazzo giungono al colmo. Take a look around you; I’ll bet you can guess there’ll be more than one pretty face that will be able to console you. Come, courage! 7 All - In war it’s foolery which must enliven the camp. Three cheers for frivolity, which alone should reign here! The vivandières brazenly take the conscripts by the arms and begin a very lively general dance. Very soon the confusion and noise are at their height. Scena XIV Detti e Fra Melitone che, preso nel vortice della danza, è per un momento costretto a ballare con le vivandiere. Finalmente, riuscito a fermarsi, esclama: Scene XIV Enter Fra Melitone, who is caught up in the whirl of the dance and for a moment is constrained to dance with the vivandières; finally, managing to extricate himself, he exclaims: 8 Melitone - Toh! Toh! Poffare il mondo! Che tempone! Corre ben l’avventura! Anch’io ci sono. Venni di Spagna a medicar ferite, ed alme a mendicar. Che vedo? È questo un campo di Cristiani, o siete Turchi? Dove s’è visto berteggiar la santa domenica così? Ben più faccenda le bottiglie vi dan che le battaglie! E invece di vestir cenere e sacco qui si tresca con Venere, con Bacco? Il mondo è fatto una casa di pianto; ogni convento ora è covo del vento! I santuari spelonche diventar di sanguinari; perfino i tabernacoli di Cristo fatti son ricettacoli del tristo. Tutto va a soqquadro. E la ragion? La ragion? 8 Melitone - Whew! Good gracious, what a world! What are things coming to? A fine to-do! And here I am. I came from Spain to heal wounds and appeal for souls. What do I see? Is this a Christian camp, or are you Turks? Where was such derision of the holy Sabbath ever seen? You’re more concerned with bottles than with battles, and instead of donning sackcloth and ashes, here you’re involved with Venus and Bacchus. The world has become a vale of tears; every monastery now is a den of empty air! Sanctuaries have become the lairs of the sanguinary; even Christ’s tabernacles have been made to receive villains. Everything’s topsy-turvy. And why? Why? 52 Pro peccata vestra: pei vostri peccati. Soldati - Ah, frate, frate! Melitone - Voi le feste calpestate, rubate, bestemmiate … Soldati Italiani - Togone infame! Soldati Spagnuoli - Segui pur, padruccio. Melitone - E membri e capi siete d’una stampa: tutti eretici, tutti, tutti cloaca di peccati, e finché il mondo puzzi di tal pece non isperi la terra alcuna pace. Soldati Italiani - serrandolo intorno Dàlli! Dàlli! Soldati Spagnuoli - difendendolo Scappa! Scappa! Cercano di picchiarlo, ma egli se la svigna, declamando sempre. Preziosilla - ai soldati che lo inseguono uscendo dalla scena 9 Lasciatelo ch’ei vada. Far guerra ad un cappuccio! Bella impresa! Non m’odon? Sia il tamburo sua difesa. Prende a caso un tamburo e, imitata da qualche tamburino, lo suona. I soldati accorrono tosto a circondarla, seguiti da tutta la turba. Preziosilla e Coro - Rataplan, rataplan, della gloria nel soldato ritempra l’ardor. Rataplan, rataplan, di vittoria questo suono è segnal precursor! Rataplan, rataplan, or le schiere son guidate raccolte a pugnar! Rataplan, rataplan, le bandiere del nemico si veggon piegar! Rataplan, pim, pam, pum, inseguite chi le terga, fuggendo, voltò! Rataplan, le gloriose ferite Pro peccata vestra, because of your sins. Italian Soldiers - Oh, brother, brother! Melitone - You profane the feast days, you rob, you blaspheme … Italian Soldiers - You villain in monk’s attire! Spanish Soldiers - Go on, old father! Melitone - Limbs and head, you’re all alike, all heretics, all sewers of iniquity, and so long as the world stinks of such pitch, let the earth not hope for any peace. Italian Soldiers - crowding round him Let him have it! Spanish Soldiers - defending him Run away, run away! The Italian soldiers try to beat Fra Melitone, but he makes his escape, still fulminating. Preziosilla - to the soldiers pursuing Fra Melitone as he flees from the scene 9 Let him go… Beating a monk! A fine thing! They won’t hear me? Then let the drum save him. She picks up a drum at random and imitates the sound of a side-drum. The soldiers promptly hasten to surround her; they are followed by all the crowd. Preziosilla and Chorus - Rataplan, rataplan, strengthens the love of glory in the soldier. Rataplan, rataplan, this sound signals victory to come! Rataplan, rataplan, the ranks are forming and are led to combat! Rataplan, rataplan, the enemy’s flag is seen to retreat! Rataplan, plan, pim, pum, pum, pursue those who turn tail and flee! Rataplan, destiny has crowned 53 col trionfo il destin coronò. Rataplan, rataplan, la vittoria Più rifulge de’ figli al valor! Rataplan, rataplan, la vittoria Al guerriero conquista ogni cor. Escono correndo. your glorious wounds with triumph. Rataplan, rataplan, the victory of one’s country shines brighter for her sons’ gallantry. Rataplan, rataplan, victory wins every heart for the soldier. All pretend to fire rifles, and rush off. ATTO QUARTO ACT FOUR Scena I Vicinanze d’Hornachuelos. Interno del convento della Madonna degli Angeli. Meschino porticato circonda una corticella con aranci, oleandri, gelsomini. Alla sinistra dello spettatore è la porta che mette al via; a destra, altra porta sopra la quale si legge “Clausura”. Il Guardiano passeggia solennemente, leggendo il suo breviario. Dalla sinistra entra una folla di mendicanti, uomini e donne di tutte le età, che portano scodelle grezze, recipienti e piatti. First Scene The vicinity of Hornachuelos. Interior of the monastery of Our Lady of the Angels. A battered colonnade surrounds a small courtyard with oranges, oleanders, jasmine. On the spectator’s left is the door leading to the road; on the right, another door above which can be read the word “Enclosure”. The Father Superior is gravely pacing up and down, reading his breviary. From the left enter a crowd of beggars of both sexes and all ages, carrying crude bowls, pots and dishes. 10 Coro di Mendicanti - Fate, la carità, è un’ora che aspettiamo, andarcene dobbiamo, andarcene dobbiam, la carità, la carità! 10 Chorus of Beggars - Give us charity, we’ve been waiting for an hour! We must be on our way. Charity! Scena II Fra Melitone entra da destra, portando un grande grembiule bianco e assistito da un converso, che porta una grande pentola a due manici. La mettono giù nel centro del cortile e il converso va via. Scene II Fra Melitone enters from the right, his stomach covered by a broad white apron. Aided by another lay brother, he is carrying a large two-handled cauldron, which they set down in the centre. The lay brother goes in again. Melitone - Che? Siete all’osteria? Quieti … Comincia a scodellare la minestra Mendicanti - spingendo continuamente Qui, presto a me, presto a me. Melitone - What? Are you at the inn? Quietly … He begins to distribute the soup with a ladle. Beggars - pushing and shoving Here, quick, give me some. 54 Melitone - Quieti, quieti, quieti, quieti. I Vecchi - Quante porzioni a loro! Tutto vorrian per sé. N’ebbe già tre Maria! Una Donna - a Melitone Quattro a me … Mendicanti - Quattro a lei! Donna - Sì, perché ho sei figliuoli… Melitone - Perché ne avete sei? Donna - Perché il mandò Iddio. Melitone - Sì, Dio… Dio. Non li avreste se al par di me voi pure la schiena percoteste con aspra disciplina, e più le notti intere passaste recitando rosari e Miserere… Guardiano - Fratel... Melitone - Ma tai pezzenti son di fecondità davvero spaventosa… Guardiano - Abbiate carità. Gli Uomini - Un po’ di quel fondaccio ancora ne donate. Melitone - Il ben di Dio, bricconi, fondaccio voi chiamate? Mendicanti - porgendo le loro scodelle A me, padre a me, a me, a me. Melitone - Oh, andatene in malora, o il ramajuol sul capo v’aggiusto bene or ora… Io perdo la pazienza! Guardiano - Carità. Le Donne - Più carità ne usava il padre Raffael. Melitone - Sì, sì, ma in otto giorni avutone abbastanza di poveri e minestra, Melitone - Quietly, quietly! Beggars - How many portions they’re getting! They want the lot for themselves. Maria’s had three helpings already! A Woman - to Fra Melitone Four for me … Beggars - Four for her! The Woman - Yes, because I’ve six children… Melitone - And why have you got six? The Woman - Because the good Lord sent them. Melitone - Yes, of course, the good Lord. You wouldn’t have them if, like me, with harsh discipline you scourged your back, and moreover spent whole nights reciting rosaries and Misereres... Father Superior - Brother… Melitone - But those beggars are really dreadfully prolific. Father Superior - Be charitable. Beggars - Give us a drop more of those dregs. Melitone - You rascals, you call this manna from heaven dregs? Beggars - holding out their bowls Me, Father, me, me. Melitone - Oh, go to blazes, or I’ll give you one on the head with this ladle right now! I’m losing patience! Father Superior - Be kind to them! Women - Father Raphael was kinder to us. Melitone - Yes, yes, but in a week he’d had enough of the poor and the soup 55 restò nella sua stanza, e scaricò la soma sul dosso a Melitone... E poi con tal canaglia usar dovrò le buone? Guardiano - Soffrono tanto i poveri… La carità è un dovere. Melitone - Carità, con costoro che il fanno per mestiere? Che un campanile abbattere co’ pugni sarien buoni, che dicono fondaccio, fondaccio il ben di Dio… Bricconi, bricconi, bricconi! Le Donne - Oh, il padre Raffaele! Gli Uomini - Era un angelo! Un santo! Melitone - Non mi seccate tanto! Mendicanti - Un santo! Un santo! Sì; sì, sì, sì, un santo! Melitone - buttando per aria il recipiente con un calcio Il resto, a voi prendetevi, non voglio più parole. Fuori di qua, lasciatemi, sì, fuori al sole, al sole. Pezzenti più di Lazzaro, sacchi di pravità… Via, via bricconi, al diavolo, toglietevi di qua! Il frate infuriato li scaccia dal cortile. Dopo prende un fazzoletto dalla sua manica e con esso si asciuga il sudore della fronte. and stayed in his room, unloading the burden on to Melitone’s shoulders. Anyway, must I treat such rabble gently? Father Superior - The poor suffer so much… Charity is a duty. Melitone - Charity for people who make a living from it? Who’d be happy to knock down a bell-tower with their fists, and call this manna from heaven dregs? Rogues and rascals! Women - Oh, Father Raphael… Men - He was an angel, a saint! Melitone - Don’t pester me so! Beggars - A saint, yes! A saint! Melitone - kicking the pot over Here, take what’s left; I don’t want another word. Get out of here, leave me, yes, out you go into the sun. You’re beggars worse than Lazarus, sacks of depravity. Be off, rascals, to the devil with you, get out of here! He drives them away, hitting them with his apron. Then mops the sweat from his brow with a white handkerchief tucked up a sleeve Scena III Il Padre Guardiano e Fra’ Melitone Scene III The Father Superior and Melitone 11 Melitone - Auf! Pazienza non v’ha che basti! 11 Melitone - Ouf! One couldn’t have enough patience for this. 56 Guardiano - Troppa dal Signor non ne aveste. Facendo carità un dover s’adempie da render fiero un angiol … Melitone - Che al mio posto in tre dì finirebbe col minestrar de’ schiaffi. Guardiano - Tacete; umil sia Meliton, né soffra se veda preferirsi Raffaele. Melitone - Io? No … amico gli son, ma ha certi gesti … Parla da sé… ha cert’occhi... Guardiano - Son le preci, il digiuno. Melitone - Ier nell’orto lavorava cotanto stralunato, che scherzando dissi: Padre, un mulatto parmi … Guardommi bieco, strinse le pugna, e … Guardiano - Ebbene? Melitone - Quando cadde sul campanil la folgore, ed usciva fra la tempesta, gli gridai: mi sembra Indian selvaggio… un urlo cacciò che mi gelava. Guardiano - Che v’ha a ridir? Melitone - Nulla, ma il guardo e penso, narraste, che il demonio qui stette un tempo in abito da frate … Gli fosse il padre Raffael parente? Guardiano - Giudizi temerari… il ver narrai… ma n’ebbe il Superior rivelazione allora… Io, no. Melitone - Ciò è vero! Ma strano è molto il padre! La ragione? 12 Guardiano - Del mondo i disinganni, l’assidua penitenza, le veglie, l’astinenza quell’anima, quell’anima turbâr. Father Superior - The Lord didn’t give you too much of it. To give charity is to fulfil a duty that would make any angel proud … Melitone - Who, after three days in my job, would end by ladling out blows … Father Superior - Hush! Melitone must be humble and not irritated to see Raphael preferred to him. Melitone - Me? No. I’m his friend, but he has certain ways… he talks to himself… he has a certain look… Father Superior - It’s the prayers and the fasting. Melitone - Yesterday in the kitchen garden he was working so furiously that in jest I said, “Father, you’re working like a black”. He glared at me, and clenched his fists, and … Father Superior - Well? Melitone - When lightning struck the belfry, and he went out into the storm, I called after him, “You’re like a wild Indian!” He let out a howl that froze my blood. Father Superior - What’s worth repeating in that? Melitone - Nothing, but I look at him and think; you told us that the devil once stayed here in monk’s clothing. Could Father Raphael be a relative of his? Father Superior - Rash judgments; I spoke the truth, but it was revealed to the Father Superior then … not to me. Melitone - That’s true, but the father’s very odd. Why is it? 12 Father Superior - Disillusionment with the world, assiduous penance, vigils and abstinence trouble his mind. 57 Melitone - Saranno i disinganni, l’assidua penitenza, le veglie, l’astinenza che il capo gli guastâr! Il campanello del cancello suona rumorosamente 13 Guardiano - Giunge qualcuno, aprite. Il Padre Guardiano esce. Melitone - It’ll be the disillusionment assiduous penance, vigils and abstinence that have addled his brain. The gate-bell rings loudly. 13 Father Superior - Someone has come. Open the door. The Father Superior goes out. Scena IV Fra’ Melitone apre la porta ed entra Don Carlo, che avviluppato in un grande mantello entra francamente. Scene IV Melitone opens the door and Don Carlos, enveloped in a large cloak, enters imperiously. Carlo - alteramente Siete il portiere? Melitone - fra sé È goffo ben costui! forte Se apersi, parmi … Carlo - Il padre Raffaele? Melitone - (Un altro!) Due ne abbiamo; l’un di Porcuna, grasso, sordo come una talpa. Un altro scarno, bruno, occhi, (ciel, quali occhi!)... Voi chiedete? Carlo - Quel dell’inferno. Melitone - (È desso!) E chi gli annuncio? Carlo - Un cavalier. Melitone - fra sé Qual boria! È un mal arnese. Melitone esce. Carlos - haughtily Are you the doorkeeper? Melitone - to himself He’s a dolt! Aloud As I just opened it, I should think … Carlos - Father Raphael? Melitone - (Another one!) We have two of them One from Porcuna, fat, deaf as a post; the other lean, dark, his eyes (heaven, what eyes!)… which one do you want? Carlos - The one from hell. Melitone - (That’s him.) And who shall I announce? Carlos - A gentleman. Melitone - to himself What arrogance! An unpleasant fellow! He goes out Scena V Don Carlo, poi Don Alvaro in abito da Frate Scene V Don Carlos, then Alvaro in a monk’s habit 14 Carlo - Invano Alvaro ti celasti al mondo, e d’ipocrita veste scudo facesti alla viltà. Del chiostro ove t’ascondi m’additò la via 14 Carlos - In vain, Alvaro, have you concealed yourself from the world, and hypocritically made a monk’s habit a shield for your baseness. Hatred and the thirst for revenge have pointed me 58 l’odio e la sete di vendetta; alcuno qui non sarà che ne divida. Il sangue, solo il tuo sangue può lavar l’oltraggio che macchiò l’onor mio, e tutto il verserò. Il giuro a Dio. Entra Don Alvaro, in abito da frate Alvaro - Fratello… Carlo - Riconoscimi. Alvaro - Don Carlo! Voi, vivente! Carlo - Da un lustro ne vo’ in traccia, ti trovo finalmente. 15 Col sangue sol cancellasi l’infamia ed il delitto. Ch’io ti punisca è scritto sul libro del destin. Tu prode fosti, or monaco, un ‘arma qui non hai… Deggio il tuo sangue spargere. Scegli, due ne portai. Alvaro - Vissi nel mondo, intendo. Or queste vesti, l’eremo, dicon che i falli ammendo, che penitente è il cor. Lasciatemi. Carlo - Non possono quel saio né il deserto codardo, te difendere. Alvaro - trasalendo Codardo! Tale asserto… frenandosi No, no! Assistimi, Signore! a Don Carlo Le minacce, i fieri accenti, portin seco in preda i venti. Perdonatemi, pietà, o fratel, pietà, pietà! A che offendere cotanto the way to the monastery where you are hiding. There will be no one here to intervene between us. Blood, your blood alone, can wash away the outrage that stained my honour; and I will spill it all, I swear to God! Don Alvaro enters in a monk’s habit. Alvaro - Brother… Carlos - Know who I am! Alvaro - Don Carlos! You - alive! Carlos - For five years I have searched for you; at last I’ve found you. 15 With blood alone can the disgrace and the crime be wiped out. That I should punish you is written in the book of fate. Once you were brave; now, as a monk, you have no sword… I must spill your blood: choose, for I have brought two… Alvaro - Once I lived in the world, so I understand; now this robe, this retreat, show that I am making amends for my misdeeds, and that my heart is penitent. Leave me! Carlos - Neither that monk’s habit nor this solitary place can protect you, coward! Alvaro - starting forward Coward! You dare to say … restraining himself Ah, no! Help me, Lord! to Don Carlos Let threats and violent words be carried away by the winds. Forgive me; have pity, brother, have pity! Why so insult one 59 chi fu solo sventurato? Deh, chiniam la fronte al fato, o fratel, pietà, pietà! Carlo - Tu contamini tal nome. Una suora mi lasciasti che tradita abbandonasti all’infamia, al disonor. Alvaro - No, non fu disonorata, ve lo giura un sacerdote! Sulla terra l’ho adorata come in cielo amar si puote. L’amo ancora, e s’ella m’ama più non brama questo cor. Carlo - Non si placa il mio furore per mendace e vile accento; l’arma impugna ed al cimento scendi meco, o traditor. Alvaro - Se i rimorsi, il pianto omai non vi parlano per me, qual nessun mi vide mai, io mi prostro al vostro pié! S’inginocchia Carlo - Ah la macchia del tuo stemma or provasti con quest’atto! Alvaro - balzando in piedi, furente Desso splende più che gemma. Carlo - Sangue il tinge di mulatto. Alvaro - non potendo più frenarsi Per la gola voi mentite! A me un brando! Glielo strappa di mano Un brando, uscite! Carlo - Finalmente! Alvaro - ricomponendosi No, l’inferno non trionfi. Va, riparti. Getta via la spada who was only unfortunate? Come, let us bow before fate; brother, have pity! Carlos - You sully such a word. Ah! You left to me a sister who, betrayed, you abandoned to infamy and dishonour. Alvaro - No, she was not dishonoured I swear it to you as a priest. On earth, I adored her as one can love in heaven. I love her still; if she still loves me, my heart asks for nothing more. Carlos - My rage is not to be placated by lying and cowardly words; take up a sword, traitor, and do battle with me! Alvaro - If remorse and tears no longer plead for me, I will do what no one has ever seen me do throw myself at your feet! He does so. Carlos - Ah, you have proved the stain on your escutcheon by this act. Alvaro - leaping to his feet in fury It shines brighter than a jewel. Carlos - It is tinted with your half-breed’s blood. Alvaro - unable to restrain himself You lie in your throat! Give me a sword! He snatches one from his hand A sword - lead on! Carlos - At last! Alvaro - recovering himself No - the devil shall not triumph. Go, leave me. He throws down his sword 60 Carlo - Ti fai dunque di me scherno? Alvaro - Va. Carlo - S’ora meco misurarti, o vigliacco, non hai core, ti consacro al disonore. Gli dà uno schiaffo Alvaro - furente Ah, segnasti la tua sorte! Morte. Raccoglie la spada Carlo - Morte! A entrambi morte! Carlo e Alvaro Ah! Vieni a morte, A morte andiam! Escono, correndo. Carlos - So you mock me? Alvaro - Go. Carlos - If now, coward, you lack courage to measure swords with me, I condemn you to dishonour. He slaps his face. Alvaro - in a fury Ah, now you have sealed your fate! Seizing the sword again Death! Carlos - Death … death to both! Carlos and Alvaro Ah! death, come forth to death! Let us go! They rush off. Scena VI Presso la grotta di Leonora. Valle tra rupi inaccessibili, attraversata da un ruscello. Nel fondo a sinistra dello spettatore è una grotta con porta praticabile, e sopra una campana che si potrà suonare dall’interno. La scena si oscura lentamente; la luna apparisce splendidissima. Donna Leonora, pallida, sfigurata, esce dalla grotta, agitatissima. Scene VI A valley amid precipitous rocks, traversed by a stream. In the background, to the spectator’s left, is a cave with a practicable door, above which is a bell that can be rung from within. The sun is going down. The scene darkens slowly; the moon appears, extremely bright. Donna Leonora, pale and worn, emerges from the cave in a state of great agitation. 16 Leonora - Pace, pace, mio Dio! Cruda sventura m’astringe, ahimè, a languir. Come il dì primo da tant’anni dura profondo il mio soffrir. L’amai, gli è ver! ma di beltà e valore cotanto Iddio l’ornò che l’amo ancor. Né togliermi dal core l’immagin sua saprò. 16 Leonora - Peace, peace, O God! Cruel misfortune compels me, alas, to languish. My suffering has lasted for so many years, as profound as on the first day. I loved him, it is true! But God had blessed him with such beauty and courage that I love him still, and cannot efface his image from my heart. 61 Fatalità! Fatalità! Fatalità! Un delitto disgiunti n’ha quaggiù! Alvaro, io t’amo. E su nel cielo è scritto: non ti vedrò mai più! Oh Dio, Dio, fa ch’io muoia. Che la calma può darmi morte sol. Invan la pace qui sperò quest’alma in preda a tanto duol. Va ad un sasso ove sono alcune provvigioni deposte dal Padre Guardiano Misero pane, a prolungarmi vieni la sconsolata vita… Ma chi giunge? Chi profanare ardisce il sacro loco? Maledizione! Maledizione! Maledizione! Torna rapidamente alla grotta, e vi si rinchiude. Fatal destiny! A crime has divided us down here! Alvaro, I love you and in heaven above it is written that I shall never see you again! O God, God, let me die, for only death can bring me peace. In vain this soul of mine here sought peace, a prey to so much woe. She goes to a rock on which the Father Superior has left food for her. Wretched bread, you come to prolong my inconsolable life. But who comes here, daring to profane this sacred retreat? A curse! A curse! She retreats rapidly into the cave, closing it behind her. Scena VII Si ode dentro la scena un cozzare di spade. Alvaro, Leonora Scene VII The clash of swords is heard. Alvaro, Leonora 17 Carlo - dall’interno Io muoio! Confessione! L’alma salvate. Alvaro - entrando in scena con spada sguainata É questo ancora sangue d’un Vargas. Carlo - Confessione! Alvaro - gettando via la spada Maledetto io sono… Ma qui presso è un eremita. Corre alla grotta e batte alla porta A confortar correte un uom che muor. Leonora - dall’interno Nol posso. Alvaro - Fratello! In nome del Signore. Leonora - Nol posso. Alvaro - battendo più forte È d’uopo! Leonora - dall’interno suonando la campana 17 Carlos - within I am dying! Confession! Save my soul. Alvaro - entering with a drawn sword This again is the blood of a Vargas! … Carlos - Confession! Alvaro - throwing aside his sword I am accursed... But nearby is a hermit… He runs to the cave and knocks at the door Come quickly, to console a dying man. Leonora - from within I cannot. Alvaro - Brother! In the name of the Lord… Leonora - I cannot. Alvaro - knocking louder You must! Leonora - ringing the bell 62 Aiuto! Aiuto! Alvaro - Deh, venite! Help, help! Alvaro - Oh come! Scena VIII Detto e Leonora che si presenta sulla porta Scene VIII The above and Leonora, who appears at the door. Leonora - Temerari, del ciel l’ira fuggite! Alvaro - Un donna! Qual voce … Ah, no… uno spettro! Leonora - riconoscendo Alvaro Che miro? Alvaro - Tu, Leonora! Leonora - Egli è ben desso. Ah, ti riveggo ancora. Alvaro - Lungi, lungi da me; queste mie mani grondano sangue, Indietro! Leonora - Che mai parli? Alvaro - indicando il bosco Là giace spento un uom. Leonora - Tu l’uccidesti? Alvaro - Tutto tentai per evitar la pugna. Chiusi i miei dì nel chiostro. Ei mi raggiunse, m’insultò, l’uccisi. Leonora - Ed era? Alvaro - Tuo fratello! Leonora - Gran Dio! Corre ansante vero il bosco Alvaro - Destino avverso, come a scherno mi prendi! Vive Leonora, e ritrovarla deggio or che versai di suo fratello il sangue! Leonora - dall’interno, mettendo un grido Ah! Alvaro - Qual grido! Che avvenne? Leonora - Rash man, flee the wrath of heaven! Alvaro - A woman! That voice!… Ah, no… a ghost! Leonora - recognizing Don Alvaro What do I see! Alvaro - You… Leonora ! Leonora - It is really he… I see you once more… Alvaro - Keep away from me… these hands of mine are dripping blood… Stand back! Leonora - Whatever are you saying? Alvaro - pointing Yonder lies a dead man. Leonora - You killed him? Alvaro - I tried everything to avoid the fight. I sought to end my days in a monastery. He found me… insulted me… I killed him. Leonora - And who was he? Alvaro - Your brother! Leonora - Great God! She rushes towards the wood. Alvaro - Hostile fate, how you mock me! Leonora is alive, and I have to find her again now that I have spilled her brother’s blood! Leonora - crying from within Ah! Alvaro - What a cry!… What has happened? 63 Scena IX Leonora, ferita, entra sostenuta dal Padre Guardiano e Detto. Scene IX Leonora comes in, wounded, supported by the Father Superior. Alvaro - Ella, ferita! Leonora - morente Nell’ora estrema perdonar non seppe. E l’onta vendicò nel sangue mio. Alvaro - E tu paga, non eri, o vendetta di Dio. Maledizione! 18 Guardiano - solenne Non imprecare; umiliati a Lui ch’è giusto e santo, che adduce a eterni gaudi per una via di pianto. D’ira e furor sacrilego non profferir parola, vedi, vedi quest’angiol vola al trono del Signor. Leonora - Con voce morente Sì, piangi e prega. Di Dio il perdono io ti prometto. Alvaro - Un reprobo, un maledetto io sono. Flutto di sangue innalzasi fra noi. Leonora - Piangi! Prega! Guardiano - Prostrati! Leonora - Di Dio il perdono io ti prometto. Alvaro - A quell’accento più non poss’io resistere. Si getta ai piedi di Leonora Guardiano - Prostrati! Alvaro - Leonora, io son redento, dal ciel son perdonato! Leonora e Guardiano - Sia lode a Te, Signor. Leonora - ad Alvaro Lieta or poss’io precederti alla promessa terra. Alvaro - She… wounded! Leonora - dying In his final hour he could not forgive… and he avenged the shame with my blood. Alvaro - And you were not to be recompensed, o God of vengeance!… Curses! 18 Father Superior - solemnly Do not curse: humble yourself before Him who is just and holy, who leads us to eternal joys by a path of tears… Do not utter a word of anger and sacrilegious fury. You see, this angel is winging her way to the throne of God… Leonora - in a fading voice Yes, weep and pray. I promise that God will pardon you … Alvaro - I am a reprobate and accursed. A wave of blood rises between us… Leonora - Weep… pray. Father Superior - Kneel! Leonora - I promise that God will pardon you. Alvaro - I can resist that voice no longer. throwing himself at Leonora’s feet Father Superior - Kneel! Alvaro - Leonora, I am redeemed, by heaven I am pardoned! Leonora and Father Superior - Praise be to Thee, Lord! Leonora - to Alvaro Gladly I can precede you to the promised land… 64 là cesserà la guerra, santo l’amor sarà. Alvaro - Tu mi condanni a vivere e m’abbandoni intanto! Il reo, il reo soltanto dunque impunito andrà! Guardiano - Santa del suo martirio ella al Signor ascenda, e il suo morir t’apprenda la fede e la pietà! Leonora - In ciel ti attendo, addio! Alvaro - Deh, non lasciarmi, Leonora, ah no, non lasciarmi… Leonora - Ah… ti precedo… Alvaro… Ah… Alvar… Ah! Muore Alvaro - Morta! Guardiano - Salita a Dio! there war shall cease, and love will be holy. Alvaro - You condemn me to live, and meanwhile abandon me! The guilty one alone then will go unpunished! Father Superior - Holy in her martyrdom, she is ascending to the Lord, and her death teaches us mercy! Leonora - I await you in heaven, farewell! Alvaro - Ah, do not leave me, Leonora, no, do not leave me... Leonora - Ah, I precede you… Alvaro… Ah… Alvar… Ah! She dies Alvaro - She is dead! Father Superior - She has gone to God! 65 Susanna Branchini (Leonora) 66 Tiziana Carraro (Preziosilla) 67 Orchestra Filarmonica Veneta “G. F. Malipiero” Coro del Teatro Sociale di Rovigo Violins: Stefano Furini*, Federico Braga*, Federica Bertevello, Michele Bettinelli, Mario Donnoli, Laura Gentili, Adina Furlanetto, Giovanni Furlanetto, Monica Miozzo, Michele Marzana, Dan Paun, Andrea Rizzi, Riccardo Sasso, Francesco Scattolin, Lavinia Tassinari, Federico Fabbris, Vicenzino Bonato, Giorgio Bovina, Chiaki Kanda, Cristina Zanolla First sopranos: Gloria Aleotti, Annalisa Alzanese, Ornella Anselmi, Stefania Bellamio*, Daniela Bortolon, Alessandra Cantin, Daniela Cavicchini, Camilla Laschi, Sandra Pozzati, Valeria D’Astoli Violas: Fabrizio Scalabrin*, Alessandro Dalla Libera, Marina Nardo, Andrea Moro, Francesca Bassan, Federico Furlanetto First tenors: Simone Bertolaso, Roberto Carli, Miguel Dandaza, Massimo Duo’, Marco Gaspari*, Stefano Nardo, Maurizio Saccani, Kim Sung Woo* Mezzos: Sara Magon, Liliana Tami, Giuseppina Trotta Altos: Marinella Paloschi, Claudia Peri, Donatella Vigato Cellos: Vittorio Piombo*, Nazzareno Balduin, Daniela Condello, Simone Tieppo, Tiziana Gasparoni Second tenors: Mirko Banzato, Cristian Bonnes, Dino Burato, Antonio Costa, Carlo Mattiazzo*, Emilio Orlando, Roberto Zacchini Double basses: Marco Ciminieri*, Davide Grespi, Carlo Nerini Flutes: Claudio Montafia*, Claudia Burlenghi Baritones: Riccardo Ambrosi*, Paolo Dalla Pria, Romano Franci, Gil Kim Hyun, Stefano Lovato*, Enrico Rolli Oboes: Stefano Romani*, Arrigo Pietrobon* Clarinets: Roberto Scalabrin*, Alessandro Toffolo Basses: Luca Dall’Amico, Marco Democratico, Giovanni Di Padua, Luca Marcheselli*, Gabriele Salvagno, Alberto Zanetti, Mario Zanetti Bassoons: Francesco Fontolan*, Roberto Lucato Horns: Massimo Capelli*, Lorenzo Meneghetti, Davide Trevisan, Alessandro Lando * solos Trumpets: Simone Lonardi*, Alberto Perenzin Trombones: Ferdinando Danese**, Alessio Savio, Fabio Rovere Tuba: Roberto Ronchetti Percussion: Mirto Cagni, Cristiano Torresan, Marica Veronese Harp: Tiziana Tornari * solos 68