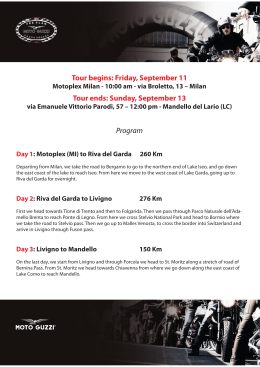

Routines of Existence : Time, Life and After Life in Society and Religion / Edited by Elena Brambilla … [et al.]. - Pisa: Plus-Pisa University Press, 2009 (Religion and Philosophy ; 4) 306.9 (21.) 1. Morte – Aspetti socio-culturali I. Brambilla, Elena CIP a cura del Sistema bibliotecario dell’Università di Pisa This volume is published thanks to the support of the Directorate General for Research of the European Commission, by the Sixth Framework Network of Excellence CLIOHRES.net under the contract CIT3-CT-2005-006164. The volume is solely the responsibility of the Network and the authors; the European Community cannot be held responsible for its contents or for any use which may be made of it. Cover: El Hortelano ( José Alfonso Morera Ortiz), (1954-), Osa Mayor 1 [The Big Dipper], 1996-1997. Image origin: VEGAP Bank of Images © 2009 by CLIOHRES.net The materials published as part of the CLIOHRES Project are the property of the CLIOHRES.net Consortium. They are available for study and use, provided that the source is clearly acknowledged. [email protected] - www.cliohres.net Published by Edizioni Plus – Pisa University Press Lungarno Pacinotti, 43 56126 Pisa Tel. 050 2212056 – Fax 050 2212945 [email protected] www.edizioniplus.it - Section “Biblioteca” Member of ISBN: 978-88-8492-650-0 Informatic editing Răzvan Adrian Marinescu Editorial assistance Viktoriya Kolp Printed Funerals in 16th- and 17thCentury Milan Massimo Petta Università di Milano Abstract During the 16th century, the growing importance of the printed book (after the time of the incunabulae) gave rise to many discontinuities. One of these involved the concept of the ‘reliability’ of the text. The use of the printing press, with its rapid processing of often ephemeral new texts made the old criterion of authority from the previous manuscript era – based on the lastingness of the text – obsolete. As many of the new texts were accounts and news, the publishers faced the problem of demonstrating their reliability. The present chapter analyzes the paratextual forms that provided the text (often having no known author) with reliability and authority: standard formats, sanctioned titles, engravings with the royal coat of arms and so on. This process of building of authority in the paratext deeply affected the Milanese editions of accounts of ceremonies. These started to describe ceremonies that had taken place in other cities, in which the reader would not have been able to take part. The propagandist and celebrative content of the ceremony was transferred to the account of it, in a booklet that was considered to be completely faithful, once it had been provided with the paratextual signs of reliability. Since that time trustworthy news and propaganda have been tightly intertwined. With the beginning of the 17th century, the editorial supply of accounts of ceremonies, for several reasons, became more diversified. In addition to the booklets, there appeared ever more luxurious celebrative books. Thus, the celebration was transferred from the text to its typographic frame: the text itself no longer needed to prove its reliability in order to achieve its propagandistic goals. As time went by, the number of splendid and exclusive books grew: these contained sumptuously decorated texts, lacking in reliability and in its paratextual signs. Their aim had switched from the precise reporting of facts to the display of their magnificent appearance. Nel corso del XVI secolo, l’affermazione del libro a stampa (dopo il primo periodo degli incunaboli) determinò diverse discontinuità. Una di queste riguardò il concetto di «affi- Printed Funerals in 16th- and 17th-Century Milan 107 dabilità» di un testo. La produzione dei torchi, con il suo rapido susseguirsi di testi sempre nuovi e spesso decisamente effimeri, rendeva obsoleti i vecchi criteri di autorevolezza della precedente età del libro manoscritto, basati sulla durevolezza del testo: essendo poi molti dei nuovi testi in circolazione racconti e notizie, il problema della loro affidabilità si poneva con urgenza agli editori. Il presente articolo analizza le forme paratestuali con cui i testi, spesso privi di autore, venivano dotati di affidabilità e autorevolezza ( formati standard, titoli omologati, silografie con le insegne dei sovrani ...). Questo processo di costruzione dell’autorevolezza nel paratesto riguardò da vicino anche le pubblicazioni milanesi di racconti di cerimonie che, a partire dal momento in cui si iniziarono a raccontare quelle avvenute in altre città (cui il lettore non aveva potuto prendere parte). Il contenuto propagandistico e celebrativo della cerimonia si riversava sul suo racconto, una notizia che, stampata in un opuscolo munito dei segni paratestuali dell’affidabilità, risultava del tutto credibile: la notizia affidabile e la propaganda da quel momento in avanti sarebbero risultate dunque profondamente intrecciate. L’offerta editoriale di racconti di cerimonie, per differenti ragioni, al principio del Seicento, iniziò a differenziarsi: oltre agli opuscoli vennero prodotte edizioni via via più lussuose, edizioni celebrative. Spostandosi, quindi, la celebrazione dal testo alla veste tipografica, il primo perdeva la stringente necessità di essere affidabile per raggiungere i suoi scopi propagandistici: si moltiplicarono quindi, nel corso degli anni, libri splendidi ed esclusivi, sontuosamente ornati, privi dell’affidabilità e dei suoi segni paratestuali, libri che non ricercavano certo l’aderenza ai fatti, ma erano liberi di seguire una apparenza magnifica. Introduction Whenever we read anything, a book, a newspaper or any other printed matter, we decide whether it could be true (i.e., if it is plausible), before deciding whether it is actually true or false. In some rare cases, we have direct knowledge of the subject matter we are reading about, and can therefore decide that the text is reliable, just because it says exactly what we expect. But, in most cases (fortunately), the texts we read inform us about matters we do not already know about directly. In order to improve our knowledge, obviously we must direct our attention to reliable accounts. But the problem is that, whereas we can decide if a speech is true or not after hearing it, we tend to decide if a printed work is reliable even before we read it. The simplest way to evaluate the reliability of a text is to consider its author: we might find out something about him, his work and his education to decide whether he is reliable or not. If the author is alive we might ask him some questions. But we cannot ask the text anything (in any case it will not reply), and in most cases, we do not know the author of the text. Moreover, some texts have no identifiable author (that is, for example, through paratextual elements1, such as front and back covers) or no individual author (a newspaper as a whole is made by many hands): in this case, we cannot rely on the ‘author’ to Death Rituals 108 Massimo Petta decide if the text is reliable. Anyway, we cannot idle in doubt forever and, few seconds after we have given a glance to the text, we decide to rely on it (or else we throw it in the trash bin, or in the junk mail folder if it is an electronic text). It is also normal to approach texts differently according to their kind. We tend to trust a handwritten text2, because we believe that it has been written just for us (or for a reader in whose place we are when we read). We can perceive the human hand of the author behind the text, so we establish a kind of relationship with him, thereby shifting our attention from the text to the author. If we have reason to suspect that the author might lie to us or if we do not trust him, we will not trust his text, perhaps deciding outright that it is false. For example, when we read an e-mail, we take first a quick look at the sender, and then we decide about the reliability of the text, on the basis of its author. If the sender is a friend of ours, we will probably think that the text is reliable (and then after analyzing it we will decide if it is true); but, if the sender is somebody we know has an interest in deceiving us, we will probably judge that handwritten text unreliable, having already evaluated the author before evaluating the text. Even historians processing documents that were not written for them frequently focus firstly on the author, in order to gauge the text’s reliability, before proceeding. In the case of a printed text, the situation is completely different. There are many identical copies of a printed text, and so it cannot be a text written ‘just for us’ (or, at least, ‘just for someone’). Thus, the parameters of reliability should be different. From the outset, we are much more confident about a printed text (paradoxically, as it was not addressed to us), on the grounds that no trickster could get away with deceiving large numbers of people. Public opinion3 is the greatest product of such a way of thinking, and it has no mercy on liars! But, of course, it is not enough for the text to be printed to ensure its reliability. It must have other features to be ‘reliable’. For centuries, there were no printed texts (printing only appeared in the middle of the 15th century), so humans were accustomed to trust only texts that addressed someone directly (with a very few exceptions). Handwritten texts are always unique examples, as they are personalized, and the reader can perceive a human being behind them, somebody that is speaking to him; he is being addressed. In fact, if the reader decides to transmit the text to someone else, he will, in turn, personalize some feature of the text (the handwriting style is the simplest and most evident example)4. In fact, the concept of ‘author’ in the era of handwritten texts was very different from our own. Printed texts are different, as they are not produced by humans, but rather by a machine. The printer, who did not write the text, does not actually write, but composes a form. It is the machine that puts ink on the paper, and produces many copies of completely identical texts, a thing that no human can do. When printed texts appeared, they had to develop a certain number of new features that marked them as ‘reliable’. These were necessary especially when the texts started to Printed Funerals in 16th- and 17th-Century Milan 109 recount things that handwritten texts did not recount, things that readers were not accustomed to read about. Meanwhile, the most cultured readers started to develop and refine a ‘critical sense’ – a modern tool that is very useful for deciding what is true, and what is not and what is reliable and what is not (flattening the two different levels). But critical reading is a complex operation that requires time, a certain level of education and some training. In the most of cases, a text is merely weighed upon its ‘reliability’, this being a quicker and easier operation than determining ‘truth’. On the question of textual reliability, the clearest example is the newspaper. Anyone opening a newspaper will first look at its name: if it is “The Times”, it will be deemed reliable and its content will be assumed to be true. If somebody asks a Times reader a question like “Are you sure?” or “How do you know?”, he may reply “I read it in The Times”. In many respects, “The Daily Mirror” is very similar to “The Times”: issued daily, printed on cheap paper, with articles, and so on (it is just more colourful). But it is not so reliable. Everybody knows it is less reliable before reading it: there is a system of extra-textual references that indicates to trained readers that “The Times” is much more reliable. Of course it is the newspaper itself that trained the readers to understand this system of extra-textual elements and thus recognize its ‘reliability’; and the training was so subtle and profound that readers usually do not know exactly why it is reliable, nor do they think about it: they just know. “The Times” constructed its own reliability, and continues to construct it every day. This system is very complex, so we shall take only two examples: the title and the format. Although the graphics have changed over the decades, the name “The Times” (like every reliable newspaper title) has remained identical for centuries. Moreover, some years ago (2003) the owner decided to reduce the size in order to increase the number of copies sold, but it took almost a year to complete the transition from broadsheet format to the tabloid one. It was also necessary for the editor, Robert Thompson, to explain the change in an editorial (30 October 2004). The operation was carried out with great caution, as it was perceived that extra-textual change could have interfered with the delicate system of extra-textual references that signals “reliability”. Printed news is not only our testing ground for evaluating the evolution of the concept of “reliability” in modern history: it was in fact the terrain where the whole modern notion of “reliability” developed, probably as a result of its potential for propaganda. In fact, the appearance of printed news publications, which developed their own (modern) reliability-tuning devices through an extra-textual system of signs, also had an effect upon social actors, such as the aristocracy and the state, which were very interested in shaping the circulation of reliable news (through financial backing or strict laws), foreseeing advantages for themselves. For centuries, before newspapers appeared, the reliability of a message was signalled in a different way. In crude terms, it was linked to the durability of the message, of the text, Death Rituals 110 Massimo Petta guaranteed by human intervention, which restored and renewed the text’s reliability at all steps of its transmission. This is illustrated by the durability of the classics: a classical author was reliable by definition. The humanist philologists worked to restore the pure ancient, original text: it was reliable, but had been corrupted by time or by unskilled medieval copyists. Nevertheless, from the 16th century, new kinds of texts, printed texts, appeared in Europe (papers, booklets, cheap books, etc.), which were initially perceived as ephemeral texts, which would not stand the test of time. Some genres, such as news sheets, tried successfully to develop new criteria for credibility by educating readers to a different sort of reliability that was not based upon durability. Today, we believe that a newspaper written by many hands and issued every day may be reliable. During the course of this process, opinions about public news changed from very negative to very positive. While, in the 16th century, newssheets were considered socially dangerous, even evil, today, public information is the basis of a democracy, a pillar of our society. This evolution also caused the adjective “new” and the noun “novelty” to acquire previously-unknown positive connotations. What is “news”? A crude definition might refer to accounts from far-away places, accounts of events in which the reader had no part. Unlike fiction, the facts that it reports have to be believed to be true. When printers started to publish these kinds of texts in the 16th century, there was no obvious reason to believe them to be true. The sole interest of the printer was to sell the publication, whether it was believed or not. Printers had no previous experience in this field, but they made an attempt. It is hard to know if there was any prior interest in having true information among readers, or if it was the publication of news that stimulated a whole new demand for ‘true accounts’. Anyhow, the great potential of printed newssheets, and their capacity to be believed, did not go unnoticed. In a period marked by wars and conflict, the various institutions of the modern state – factions, princes, churches – used propaganda for many purposes, essentially to further their stability. Propaganda, whose goal is to spread an opinion and to have it believed as a truth, developed alongside printed news and accompanied it through the centuries (in fact, even today we do not believe in totally objective information: the best we can have is information from a plurality of sources). The spread of texts (news, accounts) to be read, listened to, believed and retold as truths, is an operation that has always been deeply intertwined propaganda. If we take a retrospective look at the different forms of propaganda in modern history, it is hard to understand how some propagandistic messages could have been perceived as true. It is hard to understand how a clearly deceptive message could be believed to be true, without focusing on the fact that propaganda only works while it remains hidden. That is to say, after it has been revealed as propaganda, it no longer functions. The best place to hide propaganda is behind the reliability of a text, where it is safe Printed Funerals in 16th- and 17th-Century Milan 111 from criticism. Once it is revealed as propaganda, it becomes unreliable, and so, even without criticism, is perceived as mendacious. Not only historians – who ought to be very skilled critical readers – but almost everyone finds it easy to recognize propaganda a posteriori: in fact, it uses language that becomes obsolete and useless because of that sole use, so that, after some time, it becomes easily recognizable. If someone nowadays reads about a procession of knights of some magnificent king, he will not believe that the king was magnificent, but rather that the king wanted to appear magnificent. When propaganda is displayed, it somehow reveals itself, and so it must change its exterior forms; nevertheless, its link with “reliability” is constant. In short, in order to achieve its goals, propaganda should remain hidden behind “reliability”: to make its message believed, it has to take advantage of the extra-textual system that signifies, for the reader, ‘reliability’. So, in order to understand how it was possible for propaganda to be believed, we should not focus only on the texts themselves, but should look around them. In other words, we should study not only the un- or reliable text, but also the concept of “reliability” itself, its genesis, development and history, around the text. Paper ceremonies in Milan Public ceremonies were a particular kind of propaganda, a way of spreading texts, albeit necessarily not written (for every ceremony can itself be considered a text)5. Nevertheless, public ceremonies also produced other texts that were written: booklets, leaflets, accounts or thick luxurious volumes. In the following pages, which focus on funerals, we will explore some of the interactions between the actual ceremonies and the printed publications produced by them. We will try to explain how the development of extra-textual elements of these written texts (the core of their reliability) is deeply connected with the evolution of the text-ceremonies, and how this connection contributes to the building of a new framework for modern propaganda, with the result that it is deeply connected to modern reliability: a connection that sets reliability as its main feature, relegating the spectacle dimension to a subsidiary role. In the first part of the chapter, we will look at the arrival of the ceremony in printed form and its effects. This will allow us to identify the appearance of a modern form of propaganda, one that began to use news-texts to convey a celebratory message, while at the same time, the publishers used the celebrations to broaden the appeal of their news texts, thus creating a deep historical link between (reliable) news and propaganda, which ultimately led to modern propaganda. In the second part of the chapter, we will see the later consequence of the link between press and ceremonies: the way in which the press was exploited for the purpose of celebratory propaganda, a kind of propaganda that does not spread reliable messages, but rather displays magnificence to achieve its goals. At first, the ceremony was the medium for the celebratory propaganda texts; but later, this kind of propaganda was extended onto the printed page, which by then had become the Death Rituals 112 Massimo Petta medium for conveying reliable messages concerning (spectacular) events. By examining the development of ceremonial books, we will be able to see how these developed from reliable accounts of the actual ceremony to self-standing celebrations themselves. Some preliminary notes Before delving into the world of Milanese printed publications on ceremonies, we should make some preliminary notes about civic ceremonies. These were an opportunity to display power before the people and the aristocracy; and although they could be read at different levels, were nevertheless addressed to an undifferentiated public (the citizens). The marked differences of class and status among the citizens in the ritual order of the ceremonies exists alongside an intention to produce pure propaganda, which somehow destroys the distinctions between noblemen and commoners, lettered and illiterate, rich and poor6. A short booklet entitled Hieroglyphs in the Death of the Queen7 offers a clear explanation of the complicated (cultivated) hieroglyphs, making a very exclusive ritual accessible to (almost) everybody. The propaganda purpose is clear: it should reach as many people as possible. The propaganda aims reduce the differences in status between the citizens. It is a modern form of propaganda directed at an undifferentiated public, which has some features of “mass-propaganda” (and mass here does not mean “addressed to an enormous number of people” but rather “addressed to an undifferentiated public”). The public, the citizens: it is easy to assimilate these two concepts if we think about ceremonies, but it is not at all expected if we focus on the reader/listeners8 of the accounts. Even if it is very difficult to have a precise idea of the number of people that could actually read a text, the practice of reading aloud expands the potential number of receivers of the text. Moreover, it also transfers the crucial point from the sole number of literate people to the quality of the text. In other words, considering the circulation of the text, even an illiterate person could have received a simple, plain text, if somebody read it for him; and he could also, in his turn, recount the same text. So there is not a clearly defined public of literate readers, but rather a “potential public” of readers/listeners, whose limits are traced by the text itself9. This is relevant for news/accounts, and particularly for the ones concerning ceremonies, as they have a propaganda goal that causes them to target the broadest possible public. In short, the quality of these text traces a “potential public” that aims to include most of urban society (thereby approximating it to the public of the ceremonies). Public ceremonies in Milan had a particular feature. They were usually celebrations of the monarch, but there was no king in 16th- and 17th-century Milan, only his lieutenant (the Governatore). Thus, the ceremonies acted as propaganda not only for the former, but also, especially, for the latter, whose status was a reflection of the king’s . The lieutenant had to build his own prestige, but could not impose himself like a king: all the ‘main glory’, was for the king, who was the ‘direct object of the celebration’. Never- Printed Funerals in 16th- and 17th-Century Milan 113 theless, the Governatore was both the organizer of the celebration and the representative of the king, so if the task was carried out well, there was enough ‘indirect’ glory for him too. A celebration of the monarch organized by the Governatore was, in many respects, a form of self-celebration in disguise. Another factor we should bear in mind is that, during the parades, the ceremonial order was a very clear visual rendering of the social hierarchy: it was an occasion both for the Governatore to distribute favours, and for the aristocracy to claim or negotiate them. On the other hand, it was also an opportunity for the aristocracy to pay tribute to the Governatore, to recognize him once more as the monarch’s lieutenant, or to deny him that honour, and so contest his personal authority10. In this ‘game’, in order to shift the balance in his favour, the Governatore had a clear interest in ‘associating’ as many citizens as possible. Thus, glory was claimed before the crowd rather than the aristocracy. The noblemen had the opportunity to follow the leader in the parade, and so acquired glory while acknowledging his authority. Finally, in order to understand the evolution of publications about ceremonies in the first two centuries of the modern era, they need to be properly contextualised, since the accounts of funerals are a only part (though an important one) of a broader category of accounts of ceremonies, which is part of an accounts/news “editorial genre”. We can consider the publication of ceremonies as the intersection of two different dynamics, which are neither independent nor assimilable. In the following pages, we will analyse their growing interdependence: from the second half of the 16th century, there was a steady increase in the number of public ceremonies related to rites of passage (births, baptisms, weddings, funerals) of the king and other members of the royal family. In the meantime, a new kind of publishing appeared and quickly became popular: the news. Very often news was about ceremonies related to the life of the royal family. The main event (the topic of the news) was not the birth or the funeral but rather the luxurious exhibition, the magnificent display of majesty (the ceremony): a clear example is the publication in 1636 in Milan of an account with a title that is “shameless” in mixing different kinds of news: “True and Complete Account of the parties, jousts and tournaments held for the very happy arrival in Vienna of the Most Serene Infanta Mary of Austria […] And of the ceremonies, and Funerals made for the death of General Collalto”11. However, this was only news. The appearance of the ceremonies on the printed page Accounts of ceremonies take up a considerable part of the news sheets. They were very popular, because they were produced to be cheap and easy to understand. They also provided neutral information, mixed with spectacle (somehow analogous to our news magazines, mutatis mutandis). They were also profitable means of propaganda. For the accounts of the events in Milan (in which supposedly the readers had taken part), they functioned less as sources of information (i.e. about events one had not participated in) Death Rituals 114 Massimo Petta than as “souvenirs” (i.e. something used to remember an event one had taken part in). Nevertheless, the spectacle remained the crucial point. Let us make a quick overview of the accounts of ceremonies in Milan, in order to contextualise the accounts of funerals, their propaganda purposes and their “editorial history”. The first published account of a ceremony in Milan (in the vernacular, although there was a previous account in Latin12) is probably The entry made by the sacred Charles13 by Lessandro Verini (1533). In the following year, there appeared The magnificent triumph14 for the entry of Christina of Denmark : these resulted as mere episodes, as there was not a ‘propaganda policy’ behind either the ceremonies nor the printed account of them. The Milanese prototype for such accounts was the Treatise of the entry in Milan of Charles V (1541) by Albicante15 (then a well known literary person), which was the “typographical branch” of the propaganda machinery built by Governatore D’Avalos for the visit of Charles V (the visual arts branch was much better, as it was entrusted to Giulio Romano, a pupil of Raphael). This was a very Milanese publication: in fact the reader was supposed to have seen the ceremony (almost everybody in Milan had seen it), otherwise it is not easy to follow the account and to make sense of the engravings (which are spread randomly throughout the text). Governatore Del Vasto used printed propaganda in the following years: “The solemn ceremonies celebrated for the baptism of the son of the Marquess Del Vasto”16, “Great weeping for the death of Antonio of Aragon (1543) by Albicante”17, “La immortalità del gran marchese del Vasto”18 (1546) by Giovanni Teseo Nardi. After Del Vasto, Governor Ferrante Gonzaga too used printed propaganda: for his own entry parade (La entrata in Milano di Ferrando Gonzaga [1546]) and that of Prince Phillip (the future Phillip II) (La triomphale entrata del prence di Spagna nella citta di Melano19 [1548]), for the Prince’s entry in London (La solenne intrata Philippo e Maria nella regal città di Londra20 [1554]) and for his wedding with Mary Tudor21 (Il sacro et divino sponsalitio del gran Philippo d’Avstria et della sacra maria regina d’Inghilterra). Until this point, in Milan the situation was undefined. To simplify, there are two poles: on the one hand, the ‘court culture’ – a high, refined, exclusive culture, where the ceremony originated (and where it was still elaborated and directed), and which specialised in panegyrics for royalty; and many authors of the publications came from the court. On the other hand, there were the ordinary people, who took part in the ceremony. It was to these people that the brand-new propaganda was addressed; they constituted a much broader readership (and clientele) for the accounts. Printed papers concerning funerals accounts, news) (accounts of funerals, cheap All news, especially the most reliable, contains some degree of propaganda. The choice of which events to describe, the language used, the way the event is interpreted – these are Printed Funerals in 16th- and 17th-Century Milan 115 just the most obvious means of propagating ideas and opinions. But other considerations need to be taken into account if we are going to look at the way these funeral accounts developed, as they provide us with a good perspective on the printed accounts (of which they are a part), both in their editorial evolution and in their propagandistic value. On the one hand, there are accounts of events of every kind (battles, treaties, discoveries, etc.); on the other, there are ceremonies, celebrations (entries, weddings, funerals) with a clear propagandistic goal. The practice of celebrating some events, giving accounts of others, and publishing both the event and the celebrations in printed works that have a similar, often identical format, creates a “confusion” between the event and its celebration, a confusion that is somehow propagandistic in nature: it creates a useful kind of short circuit between event and celebration. Moreover, the celebration/account of an event gives it more appeal. In fact, the account of the celebration instead can be somehow considered a second celebration: speaking about the ceremony, it renews the same ceremony, and amplifies both the duration and the range of its ‘propagandistic’ effect. The evolution of the accounts of funerals will offer us the possibility to observe these dynamics. In the evolution of the accounts of Milanese ceremonies, there is an important turning point that coincides with a European-level event, namely the funerals of Charles V. Charles V died in Yuste (Castile) in 1558, but the news quickly reached every part of his empire and huge funerals were celebrated in every part of his domains. In Milan G.B. Da Ponte and brothers published a booklet eloquently entitled: Funerals celebrated with Solemn Pomp in the Church of the Dome of Milan for the Caesarean Majesty of Charles V Emperor and for the Most Serene Queen Mary of England, in which is Fully Described the Catafalque and the Whole Apparatus of the Church, and Are Mentioned All the Honoured People That Were Present22 (10 January 1559). It consisted of one simple sheet thickly printed and folded twice (i.e. eight pages in quarto). In the preface, the printer/author said that he would have liked to make a work comprehensible even for the reader that could not have seen the ceremony; however, knowing that he could never compete with the real ceremony (“there is no way at all to completely satisfy this desire”23), he suggests that a text like his could be read as a simple appendix to first-hand participation in the ceremony. The magnificent splendour – he thought – could not be reproduced in words. To believe it, the reader had to have seen it. This kind of account was originally intended as a sort of “souvenir”, read to support and improve the oral count, or to fix it the memory. Nevertheless, Da Ponte tried to sell his brand new one to everybody, even those that had not seen the ceremony, which explains the almost apologetic tone of the preface. Finally, this booklet is very handy and cheap (a few pages densely printed), which meant that it could be sold easily (implying a large circulation) and could be released very soon after the ceremony24. A few days later, Francesco Moscheni released an attractive 16-page booklet Descrittione della pompa funerale fatta in Brussele25 [Description of the funeral pomp made in Death Rituals 116 Massimo Petta Brussels]. Although small, it is richly engraved, depicting a large boat being pulled by sea monsters, and representations of all the emperor’s victories. Like Albicante’s prototype, it is a small booklet, rather than a newssheet. But neither author nor the source are indicated. It was produced for the market, with the aim of making money: as Da Ponte had already published the account of the Milanese funeral, Moscheni took Chancellor Taverna’s report from Brussels. But as the readers obviously could not have seen the ceremony, Moscheni thought it appropriate to illustrate the text with pictures. In 1559 two other accounts of Charles’ funerals appeared in Milan. The first26 was an anonymous reprint of Da Ponte’s work on the Milanese funerals – a very “dry” publication, due to lack of time (it was an unauthorized copy, released hastily). The second27 is similar to Da Ponte’s too, although it deals with the Brussels funerals (it is not a pirated edition of Moscheni). It is quite poor because it tries to imitate Da Ponte’s, which itself was very spare due to the lack of time (it had to be released soon after the ceremony); in this case instead there was no hurry as the news of the funeral was already old. In few months, for different reasons, the format used by Da Ponte for the accounts became popular. Probably the greatest consequence of this fact was that (funeral) accounts had become almost “instant” publications, so they were cheap, a necessary condition for texts aiming at broad circulation. In 1559, even in Cremona, an account of Charles’ Flemish funeral was published28 (by Vincenzo Conti): eight pages with no pictures, and nothing spectacular at all about the typographic appearance or the account (in fact it is little more than a list of the noblemen who attended the ceremony, neither mentioned by Taverna/Moscheni). In fact, it seems to have been released in order to gain the favour of the Castilian Alvaro de Luna. The fact that Taverna/Moscheni did not mention the noblemen (nor even King Phillip!) is important: it reveals the lack of ‘political’ oversight. The government had no direct control over these publications and the publishers were given a free rein. They were obsequious in their celebration of the king, but they focused on selling their works rather than on propaganda; thus, their accounts focus on the pomp, with little space left for the organizer of the ceremony (in this case, Phillip II), thus reducing the possibility of an effective propaganda. Nevertheless, this kind of ‘entertainment literature’ spread as the ultra-cheap format became more and more popular (it is a phenomenon that involves not only funeral accounts, but all news and especially accounts of ceremonies – i.e. Albicante’s prototype – which at the beginning were not so cheap). Thereafter, broad circulation became a ‘basic feature’ (for propaganda purposes). From Charles’ funeral onwards, publishers tried to find ever cheaper solutions; they also tried to break the link between participation and the fruition of the account (as in the case of the events of Brussels) by inventing a self-standing account, and it worked, even without pictures (which made it cheaper). Considering not only the accounts of Printed Funerals in 16th- and 17th-Century Milan 117 funerals, but every ceremony in general, the publishers also tried different registers, increasing the supply and broadening the public, which was very profitable. In subsequent years, accounts were published in Milan of ceremonies held in Brussels, Turin, France and Spain. In the following years, the Da Ponte family, which owned the biggest and most ancient printworks in Milan, published an account of the funeral of Don Carlos29 (1571), and of Anne of Austria30 (1581), together with a sermon by Cardinal Borromeo31. Nevertheless, in these years the original purely propagandistic aim that had motivated the early publications (those backed by D’Avalos and Gonzaga) was lost. In the second half of the 16th century, the publications were not the product of a planned publishing operation. Propaganda, especially the popular variety, needs constant arduous work, the type of work that could not be entrusted to the publishers, who were loyal but ultimately more interested in selling their goods, whether propagandistic or not. So, towards the end of the century, Governor Juan Fernández de Velasco intervened in order to remedy the situation. Firstly, he appointed a new royal printer, Pandolfo Malatesta (and his son Marco Tullio). This was just a part of a bigger plan. Governatore Velasco wanted to take advantage of a particular situation (the marriage of the Infante Don Felipe, and the visit of Margaret, his bride, to Milan, with great celebration and festivities; this would coincide with the entry of the new archbishop, Federico Borromeo, the cousin of the “uncomfortable” Carlo, and, as it happened, the death of King Phillip II turned the young bridegroom into king Phillip III). Velasco thought it was proper to have a reliable printworks in order to achieve his goals, which were to produce the best possible propaganda, showing himself as the good organizer of the magnificent celebrations. It was too risky to leave such an important job to a normal printer. Moreover the Da Ponte family was divided: Paolo Gottardo (the official printer to the Real Camera [Royal Chamber]) was dead and Pacifico was Archiepiscopal Printer, so there was a need for a much clearer situation. Malatesta became the new Printer to the Royal Chamber and produced a great many publications dealing with the festivities, ceremonies, parades, and so on, in which Velasco appeared as the organizer. In the years 1597-1598, which were packed full of public celebrations, the printed matter dealing in this kind of subject peaked. Most were released by Pandolfo Malatesta. Nevertheless, in the following years, the Royal Chamber Printer continued to release accounts of parades, celebrations, and other curiosities as well as regular news and articles on political subjects. In terms of production, these shared some features with modern newssheets: they were generally well standardized (8-16 pages in quarto or octavo), and bore the Royal Chamber Printer’s mark proudly on the title page as a mark of reliability. This represented not only reliability for the reader, but also for the government: a later privilege, conceded in 1636 to Pandolfo’s nephew (whose spirit we can easily extend to Pandolfo’s privilege) states clearly that “it is not fitting that these matters (news and Death Rituals 118 Massimo Petta political subjects), that interest the service of His Majesty, shall be dealt with by any hand other than that of a trusted person”32. Malatesta’s production of booklets of news and accounts had regular typographical features, thus becoming a standardized product, a publishing genre, which was simply “news”. Hence, the accounts of ceremonies and funerals were also perceived as a kind of “news”33. At that time, it was by no means obvious or natural that a text concerning a funeral of a king should be approached in the same way as another dealing with the wars of some prince somewhere. The printers did this, and inserted propaganda (accounts of ceremonies) into “news”. Thus, this kind of publication evolved, developing features of its own, after standardization, when it became even cheaper, directed at as broad and undifferentiated a public as possible. At least five distinctive features might be identified that characterize this kind of publication. Firstly, they were concerned with an interesting or a spectacular subject. In fact, despite the poor appearance of this publications, the subjects (like nowadays) were either interesting or spectacular, if it is possible to trace a clear border between the two concepts. They aimed at as broad a public as possible, people that had no direct interest in the account. This made them different from the gazettes (such as the merchants’ gazettes), to which readers subscribed in order to get particular information of interest to them34. The publishers/printers that undertook the publication of general, not-specialized information managed to catch the attention of a great number of people by inserting interesting/spectacular matters. Another distinctive feature was the fact that the matter of the account is “news”, so there is no distinction between the actual events (which might be a battle, treaty, discovery or ceremony). The “news” became a format, a receptacle, which could contain different subjects (from this point of view, it is very meaningful that a publication mixes news in the same leaf an entry and a funeral35). It also had a very cheap standard format: usually one or two densely printed sheets folded two or three times. Despite saving as much space on the sheet as possible, accounts were usually given a title page, with a coat-of-arms (of the king, emperor or pope, depending on the “protagonist” of the account, or according to the printer/publisher’s privileges). A very important feature was the fact that these accounts were written in plain language that was easy to understand and to reproduce orally, by which means the message could potentially reach a very large number of people in the urban society. Finally, there was the issue of reliability. The coats-of-arms on the title page, the imprint of the Royal Chamber Printers, are presented as a guarantee for the readers; and this takes on a deeper meaning as the years pass and the texts become increasingly anonymous. Printed Funerals in 16th- and 17th-Century Milan 119 The custom of producing a printed account of the ceremony changed the whole framework of the event. Before the appearance of these accounts, a particular ceremony was a unique occurrence and the memory of it – transmitted orally – was doomed to transformation or oblivion. To avoid the latter fate, and to provide a proper stage for the event, monuments were sometimes built to last in the centuries and act as permanent reminders of the fact that the ceremony had taken place. But the accounts were different: they fixed the memory of the event and its details. As the ceremonies moved from the space of pure oral memory to the longer-lasting “printed” memory, they ceased to be unique, as they could be easily compared with the earlier ones, favourably or unfavourably. With the printed accounts, it was possible for a large number of people to make this comparison, not only the few lucky owners of some handwritten account; and these people were largely the people who had attended the ceremony. This prepared the ground for the growing spectacularity of ceremonies: fireworks, stage, parades, and temporary architectural structures grew ever more audacious. And the architects, artists and men of letters responsible for building the stages for the parades, developed a taste for the spectacular, one of the main features of Baroque art. This spectacular quality, on the other hand, made the accounts more suitable for a broader public: funerals, carnivals, entries and weddings all merged together in the general interest in spectacle, involving an ever greater public of reader/listeners, enthralled by accounts, whose reliability was not guaranteed by reference to the speaker or the author of the account, but rather by the fact that the accounts were ‘news’, printed news, that had a complex system of para- and extra textual signs indicating their ‘reliability’ in a very modern sense. Paper Funerals (Luxury editions) After Albicante’s publication, another type of publication appeared, namely books (as opposed to simple booklets/accounts) concerning ceremonies. In fact, besides news and “official” propaganda, there was another reason for making an account of a ceremony – to adulate the king. Albicante’s Trattato de l’intrar was actually published to flatter Emperor Charles V. Every opportunity was used to ‘adulate’ the king, and the promotion of a publication was not a very expensive way for the members of the Milanese aristocracy to enhance their personal prestige before the king. It was a political gesture, in the complex social hierarchy, at whose pinnacle sat the king himself. And it was not only for the monarch; it was also an occasion to increase prestige among the readers of the book. Albicante’s work represents the prototype of “pomp publications”: we have seen how this account of pomp, including funeral pomp, met and evolved in news. Now we will follow the evolution of the publication of pomp. Funerals provided a good opportunity to adulate the dead king, to offer public condolences to the new one, to show loyalty to him. But they were more than this: funerals Death Rituals 120 Massimo Petta were also an important political moment, for the order to celebrate the funeral was usually the first order given by the new king. It represented the dynastic link and royal continuity, in terms of both family and politics. During the parades, the noblemen would display their weapons, an important point when the question is continuity or change; and many abstract treatises were produced about the death of the mortal body of the king. The funeral was the ritual representation of the very political moment of reaffirmation of continuity, the moment when the elites would pay homage to the dead body of the king and to the living body of the new king. The new monarch also claimed the subjects’ loyalty, and the loyal subjects had the opportunity to show it; a gift (such as a publication) was a convenient way for a nobleman or the Governatore to stand out of the crowd as a loyal subject. Following the accounts of Charles V’s funerals, described above under the category of accounts/news, the first ‘exacting’ Milanese publication on the occasion of a funeral was I sontuosi funerali del principe Carlo36 released in 1568. It is exacting but not exclusive; in some respects it could be a broad circulation work, while in others it is clearly directed to a small number of people, cultivated people. Firstly, the size (34 pages in folio): it is bigger than an ordinary account, though not enormous, and has no engravings or other expensive features, despite being in the most prestigious format, in folio. Then the text: the first part, while abounding in transcriptions of Latin epitaphs and scrolls, is written in smooth clear prose which is easily understandable; in contrast, the second part is a Latin oration, thus comprehensible only to the educated (particularly noblemen, as public oration was a privilege reserved for the highest magistrates of the State). To sum up, I sontuosi funerali is a work that appeals to both a narrow and a broad public; it is a made up oration, a Latin text made much more appealing by a sparkling description (in the vernacular) of the ceremonies. This work was followed by other publications concerning funeral pomp that aimed at an “upper-class” public and whose goal was to enhance the client’s prestige. These have to be inserted into a broader category of publications, in many cases concerning ceremonies, in which the client (sometimes the author himself ) orders a celebration of the event, while using it as a pretext for self-celebration. It took a long time for this kind of book to be transformed into exclusive luxury books; at first they aimed merely to be a notch above the ordinary account/news. The publications concerning funerals offer a good perspective on this evolution. However, in order to understand it better, we have to jump to the third decade of the 17th century The death of Phillip III and the subsequent funerals, in 1621, were a great occasion for the release of (obsequious) publications. The quickest was Giulio Arese, president of the Senate, the second most important post in Milan after that of Governor, and the highest rank in the hierarchy in the State of Milan. He was also the head of one of the most important families of the Duchy, which was rising in importance. He took the opportunity to offer his condolences for the death of his king by ordering the Malat- Printed Funerals in 16th- and 17th-Century Milan 121 estas (the Royal Chamber Printers) to publish a thick account of the ceremonies. The result is Il Racconto delle sontuose esequie37, a 48-page quarto volume, released soon after the news of the king’s death arrived in Milan38. Like some of the other works already described, it is addressed to an educated reader, while also containing many features of a publication for broad circulation. The cultured reader could have appreciated the accurate description of the Latin scrolls and inscriptions, the Greek “delights”, the mottos and the emblems, the Latin poetry. Nevertheless the cultured reader could also appreciate the fresh, spectacular, nevertheless reliable, description of a parade, its magnificent pomp, like anybody else who bought a cheap account/news. Let us focus on the format. It consisted of 48 pages in quarto, with some engraved frames at the beginning, a clear, simple but elegant composition. It is a medium-quality work; i.e. even if it is directed at a smaller more select public, it is not an exclusive book, but as cheap as possible in order to reach the largest public possible. This is a common feature of the broad circulation account/news: it is the desire to reach as many people as possible. Broad circulation, for the accounts/news, means potentially everybody in the city; for in addition to being read directly, these texts would also be read aloud in social readings and then recounted at second hand, which were all different ways of spreading the texts. The texts themselves leave us in no doubt: they could easily have been read and understood by almost everybody in urban society. A broad readership for an exacting book like the Racconto delle sontuose esequie implies a preliminary filter among the readers, a smaller group of cultivated people, but after this filter there are no more exclusions. To aim at a readership that was as large as possible may be obvious for any ordinary book; but why should an important nobleman be so interested in reaching a large public? Why did Giulio Arese not finance an exclusive prestigious book instead? For a book that was so important to him (it would have raised his own prestige considerably), why should he attempt to reach a broad public? In other words, why was this book not magnificent, luxurious and very expensive? Although we cannot discount the fact that he may not simply have wished to part with such a large sum of money, the real reason may lie just below the introduction: “From the press, 2 June 1621”39. This means that it was released very quickly, the day after the funeral. The author makes no mystery: “The Reader is advised that, for the great hurry, it was not possible to correct the Printed matter: and for this reason many errors have been seen”40. It was released quickly because it had a propaganda purpose (i.e. to increase Arese’s prestige). The printed propaganda “scheme” in Milan was well known: its fulcrum was the accounts/newssheets released by the Royal Chamber Printworks, which were official publications, quick, reliable, as cheap as possible and addressed to as large a public as possible. So, Arese turned to the Malatestas for his own ‘propagandistic operation’, trying to present his book like an official publication (it is opened by the order of PhilDeath Rituals 122 Massimo Petta lip IV to celebrate the funeral41), taking advantage of his public position, and wishing to publish a quick, reliable publication, and as cheap as possible. In other words, this book follows the scheme of the propaganda account/newssheet, but at a higher level, aiming for a more distinguished public. In any case, Arese was not the first to pay homage to the king: the Governatore, Duke of Feria, had preceded him. In fact, the duke had released, one day before the funeral, a gorgeous engraving of the catafalque, drawn by Giovanni Leo Rinaldi (the architect of the catafalque), engraved by Bassano and printed by Malatesta. This work was in fact part of the preparations: it was released one day before the funeral in order to whet people’s appetites for the ceremony. It is a very good engraving, harmonious in its composition, elegant in its stroke, grand on the whole; the text is perfectly integrated in the apparatus, whose elegant golden proportions fill the space in the sheet, without being too dense, thanks to Bassano’s stroke, detailed but always light. It is also remarkable because for the first time it inserts an engraving-as-artwork in the pomp/propaganda scenery (this was not by chance; not long before the art of the engraving was re-born in Milan, after many decades of neglect). Fig. 1 The catafalque for Phillip III in the Duomo (etched by Cesare Bassano; drawn by Giovanni Leo Rinaldi) La mole funerale et sontuoso apparato, Milan, Malatesta, 1621, in Biblioteca Nazionale Braidense, Milan – courtesy of Ministero per i Beni Culturali e Ambientali. Printed Funerals in 16th- and 17th-Century Milan 123 In a few days, the funeral of Phillip III had given rise to a new feature in printed propaganda – the engraving, added by the Governor, the Duke of Feria, while, at the same time, one of the most important noblemen of Milan, Giulio Arese, was following the ‘official printed propaganda’ scheme and improving upon its features, in keeping with his high social rank. Giulio Arese might have been the first nobleman to sponsor a publication in homage to the dead king, but he was not the only one: he was soon followed by Fabio Visconti Borromeo, member of another of the most important families of the Duchy. The result was a book released on 11 August, a funeral oration pronounced by Hieronimo de Florencia in Madrid, a book made of second-hand but nevertheless useful materials. In his “strategy”, Fabio Visconti Borromeo took as model another publication sponsored, some years before, by another member of his family, Carlo (we can notice that the Milanese aristocracy was not courageous in the field of books): the model was Relatione del funerale et esequie fatte in Milano42, released in 1612 on the occasion of the funerals of the Queen of Spain, Margaret of Austria. This work, after the obvious dedication and the transcription of the King’s letter ordering the funerals, combined the description and, finally, the oration in Latin. Giulio Arese’s response soon arrived: an improved reprint of Racconto delle sontuose esequie. The main novelty of the new printing was a pair of engraved pages bearing many abstruse pictures, each one representing a word: combined they formed an epigram: This was gently explained in note form for those that were not adept in the art of interpreting emblems. Giulio Arese’s operation was also supported by another member of his family, his brother Paolo, bishop of Tortona. In fact, although the Milanese Senate had appointed Paolo Belloni as official orator, the cardinal had invited four bishops to the celebration. One of these was precisely Paolo Arese, who had become bishop just one year earlier. Paolo was not permitted to say a single word from the Milanese pulpit, but he was named in Racconto delle sontuose esequie, the book sponsored by his brother Giulio. Then, adding his contribution to the whole family strategy, he published his own oration, with features not unlike those of Giulio’s Racconto. It was published by a different printer, and was a fairly cheap edition (quite ornate but consisting of only 24 leaves) and had been produced quickly (there are some significant errata). It was dedicated to the Duke of Feria, and translated into Italian (Belloni, the orator of the Senate, published his oration only in Latin). In other words, it was addressed to as many people as possible. In fact, in order to reach a wide readership, it was printed on two different qualities of paper, and included some pages of sonnets and other poems, clearly designed to make it more graceful. In brief, the chief protagonists of the paper funerals of King Phillip III were the Duke of Feria (obviously), the Arese family and Visconti Borromeo: in other words, the elite of Milanese aristocracy, in open order after the Governatore. Following the Governor, both in chronological order and in pursuing his “model” of propaganda/celebration based on Death Rituals 124 Massimo Petta the account, a celebrative account, nevertheless an account, whose main features were quickness, large (as possible) circulation, reliability (enforced by the turning to the Royal Chamber Printers, and a wise use of the coats of arms), and so on. The Governor, in any case, introduced a new element in this field: the engraving. We have seen that it was a preview, a reliable preview, of the “centre” of the pomp (the catafalque); nevertheless it introduced a new element in the celebrative printed matter: the engraving. In the following years, we notice numerous engravings in celebrative books, due also to the progress made by the visual arts in Milan (engraving is of course a form of visual art, and its development cannot be separated from the broader artistic environment). The most obvious (and significant) effect was that the celebrative books became more and more luxurious, more and more expensive. The rising costs for publishing celebrative books played an important role in changing the nature of the clientele, from single aristocrats to the aristocracy as a body. Moreover, in the third decade of 17th century, the expensive publication of the official History of Milan was the debut of Cameretta (the City Council, the most representative body of the Milanese aristocracy) as a client for a luxurious edition: the aristocracy as a body in the following years committed important resources in sponsoring celebrative books, in competition with the Governatore, a competition that was not bitter but very polite, that nevertheless brought the celebrative book to a very high degree of sumptuousness. The funeral of Queen Isabella of Austria43 in 1644 is a good example of the ‘new taste’ for the celebrative publications44. And it is remarkable that the most important element, the catafalque, not only follows the example of the 1621 engraving, but it also makes the catafalque the hub of the symbolic and visual apparatus, both of the ceremony and of the book. But let us trace the development, going directly to the following funeral of the king. Phillip IV died on 17 September 1665, and 3 months later in Milan sumptuous funeral rites were organized. An important aspect of the celebration was the publication of a commemorative book, Esequie reali45 edited by the Jesuit Barella and printed by Marco Antonio Pandolfo Malatesta. Although this was not as magnificent as some previous editions (probably speed of release was taken into consideration, due to the importance of the event), it is nevertheless a sumptuous volume, with an engraved frontispiece and five other engravings, among which the one with the catafalque is really beautiful and magnificent. Like any celebrative book, this one celebrates not only the King but also the Governor, now Luis Guzmán Ponce de León, flanked (in the foreground, with reverence) by some representative members of the aristocracy. In fact, in many respects, this volume represents a celebration of the concord among the high Milanese officials and the promise of loyalty to the new king placed in the hands of the Governor. After the description of the pomp and the funeral oration (recited by a senator), there is a meaningful chapter enti- Printed Funerals in 16th- and 17th-Century Milan 125 tled “Account of the Solemnities Held in Milan for the Vow of Vassalage to His Majesty King Charles II our Lord in the Hands of the Very Excellent Lord Luis Guzman Ponce de Leon, Governor and General Chieftain for H.M. in This State”46. Then Diego Zapata, the High Chancellor, swore allegiance to the new king, Charles II47, and finally Bartolomeo Arese, the President of the Senate (and one of the most powerful Milanese men during the period of Spanish domination), expressed gratitude, on behalf of all the Milanese ministers, to the Governor for having confirmed them in their places48. It is remarkable that the ‘chief editor’ of this book was Gerolamo Stampa49, entrusted by the Governatore both to organize the funeral50 and to edit the book: for, as regards the latter, he in fact only wrote the dedication, and entrusted the ‘executive editing’ to the Jesuit Giuseppe Barella. Nevertheless, Gerolamo Stampa was officially responsible for both the ‘real’ funeral pomp, and the ‘paper’ pomp. These are two separate ceremonial spaces. This is no longer a question of a ceremony and its account, linked by a relation of truthfulness/reliability, as in the previous funerals; rather, these are both examples of celebrative pomp, one taking place in the streets and cathedral, and the other on paper. The paper version did not merely contain a reliable account. To understand exactly what this “loss of reliability” means we should focus on the pictures of this book. For example, we might compare the picture of the catafalque of Isabella (1644) with the picture of Phillip’s. In the former, the apparatus is inside the church; there are some people looking at it, noblemen, poor people, friars, beggars, children playing, two dogs, and some candles. In short, it is a real scene. In the latter, however, the catafalque is alone on the white page, looking unreal in a non-dimensional space, detailed but without any human presence or localization. While we can easily believe that the picture represents the real catafalque, the same picture gives us no elements to make us believe it is true; reliability is not its purpose. This discourse is identical for the publication for the other funeral celebration of Phillip IV, which took place in the church of Santa Maria della Scala on 3 February 1666. For this event, in fact, another magnificent book was released, Monumento alla grandezza reale, by Pietro Giuseppe Ederi51, adorned with beautiful engravings. But the most “unbelievable” is the picture of the catafalque in the book released for the funeral of the king in the church of St. Fedele52: over the catafalque two pictures are hanging, a coat of arms and a scroll. They are not mere ‘text’ inserted in the empty spaces of the main picture; they are part of the same picture, and the drapery in which they are enveloped is as real as the marble of the architecture, as real as the candles it slips between. Let us conclude with a funeral that is neither a king’s nor a queen’s, but which was – on paper – even more magnificent than any royal one. In 1671, the young wife of the Duke of Osuna died. The widower ordered magnificent funeral rites in honour of his adored wife, the last proof of his love. Magnificent celebrations took place both in the cathedral and on paper. The result of the latter is one of the most beautiful Milanese Death Rituals 126 Massimo Petta Fig. 2 The catafalque for Phillip IV in S.Fedele. From: Il sepolcro glorioso ornato dalla pietà dell’insigne Congragatione dell’Entierro, Milan, nella stampa archiepiscopale, [1666]. Biblioteca Nazionale Braidense, Milan. Courtesy of Ministero per i Beni Culturali e Ambientali. Printed Funerals in 16th- and 17th-Century Milan 127 books, the Teatro de la Gloria53. It is a splendid edition, not only for the rich apparatus of decorations, but also for its elegant composition. It was released first in Spanish, illustrated with ten large beautiful engravings. This was soon followed by a bilingual (Latin/Italian) edition, with two columns of text (Italic Latin and Italian), with the different scripts combined very harmoniously. This book is itself a celebration, just like the one that took place in the streets and in the cathedral, and does not appear designed to pay the ‘real’ celebration a tribute of ‘reliability’: on the contrary, it is a pure paper funeral, and uses all the possibilities of paper to display its magnificence. The paper is not only the place for the display and the eternizing of the luxurious but ephemeral ceremonies, The paper has now become another space where the authors create another great ceremony. Let us look more closely at the engraving of the place. Firstly, we could compare it with the engraving made for the funerals of Cardinal Monti, as they both represent the crowded Cathedral Square. At first sight, the Duchess’s funeral is much more magnificent while the Cardinal’s seems much more realistic, despite the fact that the former is drawn more accurately and with more detail. This first impression is due the natural and varied stances of the human beings depicted in the Cardinal’s scene, as opposed to the unnaturally rigid soldiers on the Duchess’s stage. Although “naturalness” is not synonymous with “reality” or “verisimilitude”, as it is in any case an artistic code, the engraving of the Duchess’s funeral seems less realistic, less reliable. What is important is that it does not claim to be a reliable representation of the event; it is a stage, a paper stage, and there is no element that is not staged; the engraved soldiers do not represent human beings, they are an engraved scenic element, perfectly symmetrical. Every stroke is theatrical, and there is no place for non-scenic elements, such as the architecture of the cathedral, which is hidden in a background, like stage machinery. The result is that the scene on paper is gorgeous, which was its goal, and therefore complete. It was not aiming to render the actual scene in the Cathedral Square. The authors intended the engraved scene, the paper funeral, to be admired for its magnificence, not as a realistic representation of the parade. The real one was ephemeral, while the printed one is eternal, and now the people can admire only the latter: the stage is on paper, and the representation goes on. To sum up, then, these luxurious celebrative books evolved out of accounts of real events, which used the spectacularity of the ‘real’ event, as it was not thought that they could be spectacular by themselves. In the very long development that began in the second half of 16th century, their potential was gradually exploited, turning them into magnificent books. In this process, they started out as very close to the cheap news/accounts, sharing with these the characteristic of reliability: this feature gave them access to spectacularity. Once their capacity for being spectacular by themselves had been developed, celebrative books no longer needed to be reliable, and they broke the link with the accounts aimed at broad circulation, finally becoming sumptuous and exclusive books. Death Rituals 128 Massimo Petta Conclusions From the fourth decade of the 16th century in Milan, small publications appeared giving accounts of ceremonies. It was the release of Albicante’s Trattato de l’intrar in 1541 that represented the starting point for this kind of publications. This was the editorial part of a propaganda mechanism organized by Governatore D’Avalos to show off his conduct before the Emperor Charles V, and soon became the prototype for publications about ceremonies. This kind of publication was a novelty, but it was successful, and resulted in an evolution in two directions. The first one led towards news/accounts, an ‘editorial genre’ that was on the increase. For many aspects this was the consequence of the need to contain costs and to reach as broad a public as possible; the Milanese publishers tried cheaper and cheaper formats, did without engravings, thus producing more and more ‘uniform’ publications. The reliability of these publications – the main feature of news – in this way started to move away from the text (which was plain and similar to many others of the same kind) and started to lie in the extra textual elements: these elements, in the meantime were configuring a process led by the need to contain costs and to aim for a broad public. A crucial point in this process were the funerals of Charles V: Milanese publishers faced the need to recount a spectacular event that their readers had not seen (in fact until this point they had reported only Milanese ceremonies, such as Albicante’s entry of Charles V). The publishers experimented different ways of dealing with this novelty: on the one hand, Moscheni put an engraving in his work, on the other, Da Ponte used a preface to apologize for the inconvenience that the reader could not have seen the ceremony. In any case, the Milanese publishers succeeded in splitting the binomial participation/account, thus permitting the insertion of accounts of ceremonies into ‘news’. Being part of this ‘editorial genre’ they were involved in its process of standardization: in fact, the search for a cheaper and cheaper format led to the gradual renunciation of many paratextual elements such as prefaces, dedications, engravings, leaving just a rough text after the title page as the first page. Even the title became more and more standardized: most begin with Relatione [report] (or Ragguaglio or Avviso, which are synonymous), and bear a coat of arms and the name of the publisher. In sum, a few elements – in a standardized form – proclaimed the reliability of the account. Moreover, the ever cheaper format, together with a smooth language that was easy to read and easy to retell, broadened the borders of the potential public of readers and listeners of these publications. The appointment of the Malatestas as Royal Chamber Printers (1597) represented an important point in the process of adjustment/standardization of the news: firstly, they monopolized the publication of news and they adjusted their production in a standard format that was one or two printed leaves folded two or three times (i.e. 8-16 pages in 4° or in 8°). Although this process had begun before the arrival of the Malatestas, their contribution is important because they definitively consolidated it. They also added an ‘official’ character to the reliability building process. In fact, in their title pages – which, for these publications was a kind of declaration of reliability of Printed Funerals in 16th- and 17th-Century Milan 129 the news inside – they proudly showed the title of official Printers to the Royal Chamber. On the one hand this testifies to the control of the State over the news, and, above all, it made a great contribution to moving the criteria for determining reliability, out of the text. In many respects, the guarantee of reliability of such news text was neither in the text, nor in its author, but in the title page. This form of reliability that we have called “modern”, is the not very distant ancestor of the reliability that readers nowadays attribute to some newspapers, in which the title and the format are identical every day, despite the text’s being different. In fact, the features of title page and the format of the Malatestas’ news were invariable, thus giving a shape to the extra textual system that signified reliability (standard format, authoritative publisher, public circulation). This reliability was also strictly connected to the official nature of the news, since its official appearance was a very important feature of the title page. This overlap between ‘official’ appearance and reliability created a propaganda potential that was deliberately used by the governors of Milan. Moreover, the news format contained indifferently accounts of events and accounts of celebrations of events (the ceremonies were celebrations of events, such as a royal wedding – which was not at that time gossip, but rather a political event like a treaty). This confusion between a (reliable) fact and the (propagandistic) celebration contributed to create a fertile ground for propaganda itself. In other words, from the 17th century, the Milanese news, the Malatesta official news, merged reliability and propaganda in the same text format, building for the former a standard system of repetitive extra textual elements, and leaving the latter to spectacularity and easy to understand accounts of magnificent ceremonies. In the second part of the chapter we have seen that, besides this propaganda aiming at the broadest possible public (like the actual ceremonies), there emerged another way to exploit the ‘propaganda potential’ of the accounts of ceremonies. In fact, the Milanese aristocracy tried to take the opportunities provided by important events, even on a political level, such as funerals. In brief, funerals were a way of paying homage to the dead king, a recognition of dynastical continuity, a declaration of loyalty to the new king. We have been able to point out the evolution of the publications of funerals aiming at a ‘higher public’ by focusing on the great differences between the books released after Phillip III’s funeral, and the ones after his son’s funeral. In an important stage as the celebrations of the funeral of Phillip III, two of the most important Milanese families (Arese and Visconti Borromeo) displayed their printed homage to the king. They somehow repeated the “propaganda scheme” used by the Governor with the Royal Chamber Printworks of the Malatesta family. Its main elements were the quick release of the printed account and as broad a public as possible. Nevertheless, in the final product there were some differences that concerned mainly the “broad as possible” public. The cheap news/account of ceremonies, in fact, aimed at a wide public of readers/listeners that in many respects could potentially have been as wide as the public at the actual ceremonies. On the contrary, the publications sponDeath Rituals 130 Massimo Petta sored by the noblemen clearly did not aim at such a large public. Even if these books aimed at a “broad-as-possible” public, in their case “as possible” indicates a different public. In fact, these books, on the one hand, upgrade the mere account of the event, by adding more exacting texts (in Latin, for instance), prefaces, dedications and so on. This increased the number of pages, making them not only a simple cheap account, but rather a book, a bit more expensive. So, the public of these books was selected for its education and its available money. On the other hand, this selection was far from being strict: these were not really very exclusive books, as their format was not very expensive, and their language was not very sophisticated. In short, we notice that, except for the necessary improvements (these were a homage to the king) that distinguish them from the cheap news/accounts, the books aim at another ‘broad as possible’ public, just like the news accounts. In many respects they are an ‘improved form’ of cheap news, but they still retain the main feature, the broad-as-possible public: a public that was obviously smaller than the one of the cheap accounts (some education and some money were required), but it was nevertheless the broadest possible due to the more exacting nature of the book. The consequence of this fact was that, despite very rich clients whose goal was to make a distinguished self celebration (a homage to the king, in front of his lieutenant and their peers), we find no display of magnificence, but rather many analogies with accounts of ceremonies, the common propaganda for (almost) everybody. But on this same occasion (the funeral of Phillip III) the Governor, the Duke of Feria, introduced a new element in the celebrative printed display for funerals: engravings. The effects of this event were enormous for this kind of publications: we have seen them in the book released for the funeral of Phillip IV (1665-1666). Firstly, the costs rose enormously, meaning that, on the one hand, the clientele was no longer single noblemen, but the whole Milanese aristocracy as a body, the City Council, and, on the other, that the public of these books was selected (first, by its price). A magnificent display of engravings and a chosen public of readers were matched by a very exacting text, entrusted to a professional in the field of eloquence: the result is a very exclusive book, the opposite of the ones released for the previous king’s funeral. It was not only the “official publication” of the City Council that was magnificent; so were the following ones, not sponsored by institutions. It was the celebrative book as a ‘public genre’ that had become magnificent. It had definitively lost its links with the news/accounts, and it displayed all its magnificence, or better, magnificence had turned into its main feature. It was no longer a celebrative account of a ceremony, but rather a self-standing ceremony taking place on paper, in which the organizers of the event could display every spectacular effect useful for generating a sense of awe and admiration. It was a real paper funeral, to complement the actual ceremony. The book of the ceremony no longer contained merely a reliable account of the ceremony, as clearly emerges when we focus on the illustrations. In fact, despite the many Printed Funerals in 16th- and 17th-Century Milan 131 engraved pictures, there is no longer any trace of the reliability: being a part of a celebration, the engravings are not intended to be ‘reliable representations’ of the actual displays, but rather scenery-elements. The magnificent book released after the funeral of the Duchess of Osuna is very eloquent from this point of view: its pictures are a magnificent stage, in which the human characters, their words, their engraved figures, play their role in that dramatic, fictional paper funeral. We have seen how, starting from publications (after the funeral of Phillip III) whose main features were still ‘borrowed’ from the ordinary news (promptness, reliability, targeting as broad a public as possible), the situation changed radically after Phillip IV’s funeral, and, finally, after the Duchess of Osuna’s funeral. Then, in an even clearer way, we find unreliable and exclusive publication, a narrow-target kind of publication, exclusive and magnificent celebrations/publications for an exclusive public, books that also functioning to glorify the aristocracy itself, a cultural product especially for the aristocracy’s own use. Notes G. Genette, Paratexts: thresholds of interpretation, Cambridge 1997 (original edition, Seuils, Paris 1987). 1 A good starting point in the immense topic of the relation between handwritten and printed texts is D. McKitterick, Print Manuscript and the search for order, 1450-1830, Cambridge 2003. With special regard to reading/listening/reception: G. Cavallo, R. Chartier (eds.), A History of Reading in the West, Amherst 1999 and particularly M. Frenk, Entre la voz y el silencio, Alcalá de Henares 1997. 2 The birth of public opinion within the broader framework of the rise of information has also been studied by M. Infelise, Prima dei giornali: alle origini della pubblica informazione, Rome - Bari 2002 and by V. Castronovo, La stampa periodica fra Cinque e Seicento, in V. Castronovo, G. Ricuperati, C. Capra, La stampa italiana dal Cinquecento all’Ottocento, Rome - Bari 1976, in Chapter 7, Giornali e opinione pubblica, (“Newspapers and public opinion”), pp. 43-52. 3 These ideas were first developed by M. McLuhan in Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man, Toronto 1962, and in Understanding Media: The Extension of Man, New York 1964. 4 D.F. McKenzie, Bibliography and the Sociology of Texts, London 1986. 5 On the “inversion of social status” in Carnivals, see M. Bachtin, L’opera di Rabelais e la cultura popolare. Riso, carnevale e festa nella tradizione medievale e rinascimentale, Turin 1979; J. Heers, Fêtes des fous et Carnavals, Paris 1983. This corrects Bachtin’s idea of carnival as an expression of a “popular culture”, and points out how the carnival in the cities, from the 15th-16th centuries, fell under the control of the municipal institutions and the state. Some ‘carnival’ elements in public ceremonies clearly emerge in Cesare Parona, Feste di Milano nel felicissimo nascimento del Principe di Spagna don Filippo Domenico Vittorio. Descritte da Cesare Parona et alla maestà del potentissimo Re Catolico n. signore dedicate, In Milano, per Girolamo Bordoni e Pietromartire Locarni, 1607; the same elements had been condemned by archbishop Borromeo in Lettera Memoriale di monsignore illustrissimo et reverendissimo cardinale di s. Prassede Arcivescovo, al suo diletto popolo della città, et diocese di Milano, In Milano, appresso Michel Tini, Stampator del Seminario, 1579. 6 Geroglifici in morte della catholica reina nostra signora D. Margherita d’Austria composti nella lingua spagnuola, tradotti nell’italiana, et nell’vna, e nell’altra stampati, in Milano, nella regia ducal corte, per Marco Tullio Malatesta, 1611, [4] l. in 4° [Hieroglyphs on the death of the catholic queen Our Lady Margaret of Austria composed in the Spanish language, translated in the Italian one, and in both printed]. 7 Death Rituals 132 Massimo Petta R. Chartier, Reading Matter and ‘Popular’ Reading: From the Renaissance to the 17th Century, in G. Cavallo, R. Chartier (eds.), A History of Reading in the West, Cambridge 1999, pp. 269-283 (original edition, Letture e lettori «popolari» dal Rinascimento al settecento, in G. Cavallo, R. Chartier (eds.), Storia della lettura nel mondo occidentale, Rome - Bari 1995, pp. 317-335). See also Frenk, Entre la voz y el silencio cit.; Id., «Lectores y oidores». La difusión oral de la literatura en el Siglo de Oro, in G. Bellini (ed.), Actas del Séptimo Congreso de la Asociación Internacional de Hispanistas, Rome 1982, pp. 101-123; H.J. Martin, Historie et povoirs de l’écrit, Paris 1988 (at chapter 2, La parola e lo scritto, pp. 47122), R. Chartier, L’ordre des livres. Lecteures, auteurs, bibliothèques en Europe entre XIV et XVIII siècle, Aix-en-Provence 1992; Id., Publishing Drama in Early Modern Europe, London 1999. 9 The ‘quality’ of the text is determined not only by the ‘pure’ text, but rather by the entire product, a sum of textual, paratextual and extra-textual elements (see McKenzie, Bibliography and sociology of texts cit.). In his fundamental work, R. Chartier, Lectures et lecteurs dans la France d’Anciene Régime, Paris 1987, demonstrates that the publishing of high literature texts in a cheap collection (the Bibliothèque Bleue) gives to the same texts a “large-circulation” nature. See also R. Darnton, History of Reading, in P. Burke (ed.), New Perspectives on Historical Writing, Cambridge 1991, pp. 140-167; C. Appel, Asking, Counting, Memorizing, in A. Messerli, R. Chartier (eds.), Scripta volant, Verba manent. Schriftkulturen in Europa zwischen 1500 und 1900, Basel 2007, pp. 191-225. 10 This notion originated with Norbert Elias, who argued that behaviour standards, or etiquette, are a complex political game, in which authority and submission are negotiated and dissimulated. The original idea was that the evolution of these standards was directed by the prince in the court in order to establish his power and to make it accepted by courtly society. Expanding the stage from the court to the city, this could be a good key to understand the evolution of the ceremonies. 11 Vera, & compitissima relatione delle feste, giostre, e torneamenti fatti per il felicissimo arrivo in Vienna della serenissima infante d. Maria d’Avstria, con l’oratione recitata in sua lode dall’eminentissimo cardinale Dietrikstain ... et delle cerimonie, & pompe Funebri fatte per la morte del Generale Coll’Alto, in Milano, per Gio. Pietro Ramellati, & Filippo Ghisolfi, 1631; 8 p. in-4° [True and very accomplished report of the festivities, jousting and tournaments held for the very happy arrival in Vienna of the most serene infante Mary of Austria, with the oration recited by the most eminent cardinal Dietrikstein ... and of the ceremonies and funeral pomp made for the death of general Collalto]. 12 It was the account of the entry of Louis XII in 1499: Ingressus xpianissimi Ludovici francorum Regis in ciuitatem suam Mediolanensis, [Milan, 1499], 4 p. in 4° [The entry of the Most Christian Louis king of France in his city Milan]. It is a unique case, at least, because of the language it is written in. It seems to be addressed to a well-cultivated reader (a member of the court?) rather than to a ‘normal citizen’. 13 Alessandro Verini, La entrata che ha fatta il sacro Carlo Quinto Imperatore Romano nella inclita città di Milano … Composta per Lessando Verini Fiorentino etc., [Milan, Gottardo da Ponte, 1533], 16 p. in 4° [The entry that made the sacred Charles V Roman Emperor in the famous city of Milan ... composed by Lessandro Verini from Florence]: bibliographical references are provided by G. Bologna (ed.), Le cinquecentine della Biblioteca Trivulziana, I, Le edizioni milanesi, Milan 1965, 492, p. 176. It has 16 unnumbered pages bound in quarto. It was released cheaply, and is old fashioned, though quite well done. It uses Roman type and two columns, features that do not appear in further Milanese publications of this kind. This is another reason not to consider this, but rather Albicante’s work (for which see below), as the prototype of this kind of publication. 14 Giovanni Battista Verini, El magnifico triompho fatto alla illustrissima: et excellentissima: duchessa, cominciando da che lentra in su lo stato per infino nella sua inclita citta de Milano. Composto per Giouan Battista Verini Fiorentino etc., In Milano, [Gottardo Da Ponte], 1534, [4] l. in 4° [The magnificent triumphal procession of the most illustrious and most Excellent Duchess starting from her entry into the State to the famous city of Milan. Composed by Giovanni Battista Verini from Florence]. The name of the publisher is suggested by Sandal, L’arte della stampa a Milano nell’età di Carlo V. Notizie storiche e annali tipografici (1526-1556), Baden-Baden, 1988, p. 47. 8 Printed Funerals in 16th- and 17th-Century Milan 133 Giovanni Alberto Albicante, Trattato del’intrar in Milano, di Carlo V. c. sempre aug., Mediolani [Milan], Apud Andrea Caluum, 1541, [28] l. in 4° [Treatise of the entry in Milan of Charles V Caesar and always August]. 15 Angelo Pendaglia, Le Solenne cerimonie cellebrate al Baptisimo del figliolo de lo illustrissimo S. Marches del uasto tenuto per le mane delo Imperator con lordine de le gran feste [Milan, 1541], in 8º [Solemn ceremonies celebrated for the baptism of the son of Marquis del Vasto, held by the hands of the Emperor, with the order of the great celebrations]. 16 Giovanni Alberto Albicante, Selua di pianto sopra la morte dell’illustrissimo ed eccellentissimo signor don Antonio d’Aragona, in Milano, per Gio. Antonio da Castiglione, 1543, [7] l, in 4°. 17 Moreover, the composition of the title page is quite similar to the one of the Trattato by Albicante. 18 Landolfo Verità, La entrata fatta in Milano alli xix. di givgno. m.d.xlvi. dallo illvstrissimo et excellentissimo signor s. don Ferrando Gonzaga, Stampata in Melano [Milan] da M. Antonio Borgio con grazia e privilegio dello Illustrissimo Senato; pp. 16, in-4° (o in-8° according to Biblioteca Trivulziana) [The entry into Milan on 19 of June 1546 by the most illustrious and most excellent Lord Ferdinand Gonzaga]. 19 La solenne… entrata delli serenissimi Re Philippo, et Regina Maria di Inghliterra, nella regal città di Londra [The solemn entry of the most serene King Phillip and Queen Mary of England in the Royal City of London], [Milan], 1554, in 4°. 20 Giovanni Alberto Albicante, Il sacro et divino sponsalitio del gran Philippo d’Austria et della sacra Maria regina d’Inghilterra; Con la unione & obedienza data alla cattolica Chiesa, sedente sommo Pontefice Giulio III. Dedicato All’Illustrissimo & Eccellentissimo Signore il s. duca d’Alba. Fabricato in ottava rima per L’Albicante Furibondo, in Milano, dai Moscheni, 1555, 94 p. in 8°. 21 Essequie celebrate con solenne pompa nella chiesa del Domo di Milano per la Cesarea Maestà di Carlo quinto Imperatore Romano, & per la Serenissima Regina Maria d’Inghilterra. Nelle quali à pieno si descrive il Catafalco, con tutto l’apparato della Chiesa, & insieme si fa mentione de i nomi di quelle persone onorate che a dette essequie furno presenti, in Milano, dalla stampa di Giovanbattista da Ponte, & fratelli alla Dovana (10 gennaio 1559), 8 p. in 4°. 22 “al qual desiderio maniera alcuna non ci è di poter a pieno soddisfare”, c. 3. 23 The same funeral of the emperor in Brussels was the occasion for a low-profile French printer named Christophe Plantin to begin to raise the quality of his publications, releasing one above the average: La magnifique et sumptueuse Pompe funebre faite aus obseques et funerailles du tresgrand et tresvictorieus empereur Charles cinquiéme, celebrées en la vile de Bruxelles le XXIX. iour du mois de décembre M.D.LVIII, par Philippes roy catholique d’Espaigne son fils, A Anvers, De l’Imprimerie de Christophe Plantin, 1559. [The splendid and sumptuous ceremony held on the occasion of the funerals of the very great and victorious Emperor Charles V, celebrated in the city of Brussels the 29th day of December 1558 by his son Philip, Catholic King of Spain]. “This appeared in 1559, and was as magnificent in its production as the funeral procession had been” (L. Voet, The Golden Compasses. The History of the House of PlantinMoretus, Amsterdam, London, New York, 1969-1972, I, p. 33). 24 Descrittione della pompa funerale fatta in Brussele alli XXIX. Di dicembre M.D.LVIII. Per la felice, & immoltal memoria di Carlo V. Imperatore, con una Nave delle vittorie di sua Cesarea Maestà, in Milano, appresso Francesco Moschenio, 1599, 16 p. in 4°. 25 Essequie celebrate con solenne pompa nella chiesa del Domo di Milano per la Cesarea Maestà di Carlo quinto Imperatore Romano, & per la Serenissima Regina Maria d’Inghilterra. Nelle quali à pieno si descrive il Catafalco, con tutto l’apparato della Chiesa, & insieme si fa mentione de i nomi di quelle persone onorate che a dette essequie furno presenti, [Milan], 1559, 8 p. in 4°. 26 Descrittione delle essequie superbissime celebrate per la morte del invittissimo Carlo Quinto Imperatore. Alla corte del serenissimo Re Filippo suo Figliolo, [Milan], 1599, [4] l. in 4°. 27 Death Rituals 134 Massimo Petta He specialized in Jewish books (thirty-seven editions, and also a Yiddish and a German one: G. Tamani, Conti, Vincenzo, in Dizionario dei tipografi, p. 338); he was the first member of a family of printers that lived and worked in Piacenza (Anteo e Francesco), Napoli (Zuane) e Milan (Paolo e Marco Antonio): A. Martegani, Uno sconosciuto stampatore milanese del xvi secolo: Paolo Conti, in Memorie storiche della diocesi di Milano, 12 (1965), pp. 487-88 and Id., Marco Antonio Conti editore milanese sconosciuto, Archivio Storico Lombardo, 1969, 96, pp. 328-329. 28 Ascanio Centorio Degli Hortensii, I sontuosi funerali fatti fare dall’illustriss. et eccellent. s. duca d’Alborquerque ... Nella morte del serenissimo principe Carlo di Spagna, in Milano, appresso di Gio. Battista, et Paolo Gotardo de Ponti alla Dogana, 1568; p. [34], in folio. 29 Pellegrino Tibaldi, Descrittione de l’edificio, et di tutto l’apparato, con le cerimonie pertinenti a l’essequie de la serenissiima d. Anna d’Austria, regina di Spagna, celebrate ne la chiesa maggior di Milano, a di 6. di Settembre, 1581. Opera di m. Pellegrino de’ Pellegrini, in Milano, per Paolo Gottardo Pontio, 1581, 60 p. in 4°. 30 Carlo Borromeo, Sermone di monsignor ... cardinale di S. Prassede arcivescovo di Milano sopra l’essequie della ser.ma d. Anna d’Austria regina di Spagna, in Milano, per Paolo Gottardo Pontio, 1581, 20 p. in 4°. 31 “[...] non conviene che simili materie, nelle quali può interessarsi il servizio di Sua Maestà, passino per altra mano, che quella di persona confidente”. This document is preserved in the Archivio storico civico di Milano, Materie 894. 32 After the assassination of Henry IV of France (1610), the Malatestas published the account of the funeral: Relatione del solenniss. apparato funerale celebrato in Parigi nella morte del christianissimo re di Francia, e di Navarra Henrico IIII, in Milano, per Pandolfo Malatesta, [1610] [Report of the very solemn funeral display celebrated in Paris in the death of the Most Christian king of France and Navarre Henry IV] in the same standard format (16 pages in-4°, only a title page with typographic notes and a coat of arms, then the plain text) as a discourse with news and a publication of diplomatic news (Discorso lagrimoso dell’insulto, e parricidio commesso nella persona di Henrico quarto …, co’l suo epitafio. Insieme con la coronatione del prencipe delfino alli 15 maggio 1610. Tradotte da Pietro Bochino Pepino, in Milano, Per li Malatesti, Impressori Regij Camerali, 1610; Confermatione della pace, intimata dal nuouo re di Francia à suoi sudditi l’anno 1610. alli 22. Maggio. Tradotta da Pietro Bochino Pepino, in Milano, per gli Stampatori Regij Camerali, [1610]). The following year, the Malatestas put in the same publication “two reports, one of the infirmity, and death of the Queen of Spain Margaret of Austria, and the other of the funeral, pomp, ornaments, dressings, and displays made until the burial” (Due relationi, vna dell’infermità, et morte della … reina di Spagna … Margarita d’Avstria ... Et l’altra del Funerale, pompe, ornamenti, vestiti, & apparati fino alla Sepoltura, Tolte dalla lingua Spagnola, in Milano, nella Corte Reg. Duc. per Marco Tullio Malatesta [1611], 8 p. in 4°). 33 See M. Infelise, Sistemi di comunicazione e informazione manoscritta tra ‘500 e ‘700, in Messeli, Chartier (eds.), Scripta volant cit., pp. 15-35; Id., Prima dei giornali: alle origini della pubblica informazione, Rome - Bari 2002. 34 Vera, & compitissima relatione delle feste, giostre, e torneamenti fatti cit. (see note 11). 35 Centorio degli Hortensii, I sontuosi funerali cit. (see note 29). 36 Emanuele Tesauro, Racconto delle sontuose esequie fatte in Milano alli 7 di Giugno l’Anno 1621, Milan, Pandolfo Malatesta, 1621, [24] l. in 4° (this work is anonymous; for the attribution cfr. C. Sommervogel, Bibliothèque de la compagnie de Jésus, VII, Bruxelles - Paris, 1896, col. 1943). 37 Breve relatione della morte del re D. Filippo III. Tradotta dalla lingua Spagnola, nella Italiana, in Milano, nella Reg. Duc. Corte, per Gio. Battista Malatesta Stampatore Reg. Cam. [1621], [4] l. in 4°. 38 “Dalle stampe li 8. Giugno 1621” (l. 2v.). 39 “S’avvisa il Lettore, che per la gran fretta non s’è potuto emendar la Stampa: & però sono scorsi molti errori”: l. 24r. 40 Printed Funerals in 16th- and 17th-Century Milan 135 “He querido auisaros paraque lo tengais entendido, y ordeneys que en esa Ciudad, y estado se hagan dello las demostraçiones funerales y los suffragios, y oraciones en general y en particular” (L. 4r) [I wanted to send you this news so that you are informed and order that in the City, and state, there be funeral demonstrations of it [mourning], prayers, and orations, in general and in particular]. Actually it is not the order to make public funerals, it is only the letter to the Governatore to inform him that the king was dead, and to tell him to order the public mourning. Nevertheless, put at the beginning of the book, it gives to the book the appearance of an ‘official publication’. 41 Relatione del funerale et esequie fatte in Milano per ordine della Cat. Maestà del Potentiss. Re di Spagna Don Filippo Terzo Nostro Signore, alla … Regina … Margherita d’Austria sua moglie, li 22 di Dicembre 1611 etc., in Milano, appresso li stampatori Archiepiscopali, 1612; 52 p. in 4°. 42 Born Élisabeth de Bourbon, nowadays in Italy she is known as Elisabetta. Instead, at that time in Milan, she was known as Isabella, which is the translation of her Spanish name, Isabel. Moreover, she should have been described as “of Bourbon” or “of France”, as she was not born a Habsburg (“House of Austria”), but in that period Spain and France were at war, so the author preferred not to underline this fact, and so he ‘adjusted’ her family name. 43 In addition to the engraving (Figure 1) there was also published the Breve descrittione dell’apparato funebre fatto per le sontuose esequie della serenissima reina Isabella nel duomo di Milano, in Milano, nel regio, e ducal palazzo, per Gio. Battista, & Giulio Cesare fratelli Malatesta stampatori R.C [1644], 36 p. in folio: it is a “celebration of the celebrative apparatus”, and also an exclusive, fine publication (even if far from being sumptuous). A further release was Matteo Bimio, Nella pompa funebre d’Isabella Borbona augustissima reina di Spagna, oratione dell’ill.mo sig.r senatore Matteo Bimio, recitata nel duomo di Milano il 22. decembre 1644 e dall’intento occupato trapportata dall’idioma latino nell’italiano, in Milano, per Gio. Battista, & Giulio Cesare fratelli Malatesta, stampatori reg. cam, in folio, which combines, on the one hand an exacting format (in folio), and, on the other, an accessible translation in Italian; unfortunately today only the title page is extant. 44 [Giovanni Battista Barella], Esequie reali alla catt. maestà del re d. Filippo IV. Celebrate in Milano alli 17 Decembre 1665 per ordine dell’eccellentissimo signore il sig. d. Luigi Guzman Ponze De Leon Capitano della Guardia Spagnuola di S.M. Cattolica, del Consiglio Supremo di Guerra, Governatore, e Capitano Generale dello Stato di Milano &c. In esecuzione del comandamento dell’augustissima reina Maria Anna nostra signora, in Milano, nella Reg. Duc. Corte, per Marc’Antonio Pandolfo Malatesta Stampatore Reg. Cam., [1666], 87 p. in folio. The name of the author appears in the dedication. There is also no date of publication, but only the date of the funeral, which means that it was released closely after the funeral. As the latter took place on 17 December, it is not certain that the former could have come about before the end of the year (British Library and Biblioteca Nazionale Braidense catalogues hypothesise that the year was 1665). Even if it is possible that in the three months that passed from the actual death of the king to the Milanese funeral, the book was also prepared, as there is a lack of explicit documents, it seems more appropriate to indicate 1666 as the probable year of publication. 45 Racconto della solennità usata in Milano per lo giuramento di vassallaggio alla Maestà del Re D. Carlo Secondo nostro Signore nelle mani dell’Eccellentissimo Sig. D. Luigi Guzman Ponze di Leon, Governatore, e Capitano Generale per S. M. in questo Stato (pp. 77-79). 46 Proposizione fatta dal Sig. Gran Cancelliere D. Diego Zapata d’ordine di S. E. nell’atto del giuramento di fedeltà prestato al Re nostro signore D. Carlo II adì 20 Decembre 1665 (pp. 80-81). 47 Rendimento di grazie all’Eccellentissimo Sig. Governatore, da rappresentarsi a S. M., fatto dal Reggente Presidente del Senato Conte Bartolomeo Aresi a nome di tutti li ministri regij per la confermazione degli offizij (pp. 83-84). 48 In Catalogues and OPACs he is often quoted as author of the book, because his name is in the dedication. 49 Death Rituals 136 Massimo Petta The book (p. 70) states that the success of the event “is due, for the most part, to the supervision very properly entrusted by the Governatore to the Marquess Don Girolamo Stampa” [“in gran parte si dee alla soprintendenza tanto provvidamente da S. E. appoggiata al Sig. Marchese Don Girolamo Stampa”]. 50 Pietro Giuseppe Ederi, Il Monumento della grandezza reale alzato alla gloriosa memoria del re catt. D. Filippo IV. il grande per le sollenni esequie fattegli a 3. di febbraio 1666. in Milano nella regia cappella e collegiata di S. Maria della Scala e consegrato da quel capitolo all’Augustissima reina Maria Anna nostra signora, in Milano, nella regia ducal corte, per Marc’Antonio Pandolfo Malatesta stampatore regio camerale [1666], 80 p. in folio. 51 Il sepolcro glorioso ornato dalla pietà dell’insigne Congragatione dell’Entierro di Cristo N.S. nell’essequie della maestà di Filippo Quarto nella chiesa di Santo Fedele de PP. della compagnia di Giesù, Milano, li 16 Genaro 1666, in Milano nella stampa archiepiscopale, [1666]. 52 [Giovanni Battista Barella], Teatro de la gloria consagrado a la excelentisima señora doña Felice De Sandoval Enriquez duquesa de Uceda defunta, por el excelentisimo señor don Gaspar Tellez Giron duque de Osuna, conde de Ureña, Governador del Estado de Milan, y Capitan general en Italia, en solemnes esequias celebradas en Milan, [Malatesta, 1672]: the name of the author is written with a quill pen by a 17th century librarian in one of the title pages of the exemplar of the Biblioteca Nazionale Braidense (“Auctor operis et descriptor fuit Pater Io: B.ta Barella soc.s Iesu.”). Barella, moreover, had previous experience in this kind of publication (Esequie reali, 1666); We can easily suppose the printer was Malatesta, although this is not stated. Finally, for the year of publication (the funeral took place on 26 October 1671) I refer to the considerations in note 45. 53 Bibliography Bertelli S., The King’s body: the Sacred Rituals of Power in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, University Park 2001 (original edition, Il corpo del re. Sacralità e potere nell’Europa medievale e moderna, Florence 1995). Bouza F., Imagen y propaganda: capitulos de historia cultural del reinado de Felipe II, Madrid 1998. Castronovo V., La stampa periodica fra Cinque e Seicento, in Castronovo V., Ricuperati G., Capra C., La stampa italiana dal Cinquecento all’Ottocento, Rome - Bari 1976, pp. 1-66. Castillo Gomez A. (ed.), Escribir y leer en el siglo de Cervantes, Barcelona 1999. Cavagna A.G., Printing and Publishing in XVII Century Lombardy, in “Guthenberg Jahrbuch”, 1998, pp. 208-216. Chartier R., Lectures et lecteuers dans la France d’Anciene Régime, Paris 1987. Id., Reading Matter and ‘Popular’ Reading: From the Renaissance to the 17th Century, in Cavallo G., Chartier R. (eds.), A History of Reading in the West, Cambridge 1999, pp. 269-283 (original edition: Letture e lettori «popolari» dal Rinascimento al settecento, in G. Cavallo, R. Chartier (eds.), Storia della lettura nel mondo occidentale, Rome-Bari 1995, pp. 317-335). Id., Publishing Drama in Early Modern Europe, London 1999. Id., Texts, Printing, readings, in Hunt L. (ed.), The New Cultural History, Berkeley 1989, pp. 155-175. Darnton R., History of Reading, in P. Burke (ed.), New Perspectives on Historical Writing, Cambridge 1991, pp. 140-167. Dooley B., Baron S. (eds.), The Politics of Information in Early Modern Europe, London - New York 2001. Frenk M., Entre la voz y el silencio, Alcalá de Henares 1997. Fox A., Cheap Political Print and its Audience in Later 17th-Century London, in Messeli A., Chartier R. (eds.), Scripta volant, Verba manent. Schriftkulturen in Europa zwischen 1500 und 1900, Basel 2007, pp. 227-242. Printed Funerals in 16th- and 17th-Century Milan 137 Genette G., Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation, Cambridge 1997 (original edition: Seuils, Paris 1987). Grandis S.G., Teatri di sontuosissima e orrida maestà. Trionfo della morte e trionfo del re nelle pompe funebri regali, in Cascetta A., Carpani R. (eds.), La scena della gloria. Drammaturgia e spettacolo a Milano in età spagnola, Milan 1995, pp. 659-715. Infelise M., Prima dei giornali: alle origini della pubblica informazione, Rome - Bari 2002. Id., Sistemi di comunicazione e informazione manoscritta tra ‘500 e ‘700, in Messerli A., Chartier R. (eds.), Scripta volant, Verba manent. Schriftkulturen in Europa zwischen 1500 und 1900, Basel 2007, pp. 15-35. Heers J., Fêtes des fous et Carnavals, Paris 1983. Kipling G., Enter the King, Theatre, Liturgy and Ritual in the Medieval Civic Triumph, Oxford 1998. Leydi S., Sub umbra imperialis aquilae, Florence 1999. McKenzie D.F., Bibliography and the Sociology of Texts, London 1986. McKitterick D., Print Manuscript and the Search for Order, 1450-1830, Cambridge 2003. McLuhan M., Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man, Toronto 1962. Mellot J.-D., On the threshold: Architecture, Paratext, and Early Print Culture, in Baron S., Lindquist E.N., Shevlin E.F. (eds.), Agent of Change: Print Culture Studies After Elizabeth L. Eisenstein, Amherst - Washington 2007. Sandal E., L’arte della stampa a Milano nell’età di Carlo V. Notizie storiche e annali tipografici (1526-1556), Baden-Baden 1988. Death Rituals