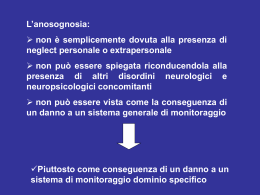

Department of Psychology, Neuropsychology Research Group, University of Turin Anna Berti Intenzione e consapevolezza: evidenze dall’anosognosia per l’emiplegia Torino, 12 maggio 2009 So long as the brain functions normally, the inadequacies of common-sense framework can be hidden from view, but with a damaged brain the inadequacies of theory are unmasked. Patricia Smith-Churchland, Neurophilosophy,1986 -L’esperienza soggettiva che abbiamo di noi stessi è caratterizzata, in condizioni normali, da una sensazione di unitarietà. Da qui coscienza e l’autocoscienza caratterizzate da una struttura unitaria e monolitica Alcune particolari sindromi neuropsicologiche possono costituire una sorta di grimaldello per sradicare delle credenze consolidate relative ai sistemi di consapevolezza. LA STRUTTURA DEI PROCESSI COSCIENTI Previsioni diffferenti Un danno cerebrale dovrebbe causare: 1. Struttura unitaria 2. Multicomponenziale 1. Un disordine generalizzato di consapevolezza 2. Disordini selettivi Gli studi lesionali sono in grado di svelare la multicomponenzialità dei processi di coscienza -Negligenza spaziale -Anosognosia per l’emiplegia Disordini di consapevolezza dominio-specifici disordini dove un danno cerebrale non comporta una perdita generalizzata di consapevolezza, ma una perdita di consapevolezza relativa al prodotto di un processo cognitivo 1. Presentazione clinica 2. Interpretazione del disturbo Definizione In generale negazione della malattia anosognosia per l’emiplegia (Seneca, lettere a Lucilius, epistula IX, Citato da Bisiach e Geminiani, 1990) Harpestem, uxoris meae fatuam, scis hereditarium onus in domo meae remanisse . . . Haec fatua desiit videre. Incredibilem rem tibi narro, sed veram: nescit esse se caecam; su binde paedagogum suum rogat ut migret, ait domum tenebricosam esse. . . . et ideo difficulter ad sanitatem pervenimus quia nos aegrotare nescimus. Tu sai che Harpeste, una sciocca amica di mia moglie, è rimasta a casa mia come un fardello ereditato. Questa folle donna ha improvvisamente perso la vista. Non solo, ora ti dico una cosa incredibile, ma vera. Ella non sa di essere cieca. Chiede continuamente di essere riportata da un’altra parte dal suo guardiano poiché sostiene che la mia casa è buia. . . . è difficile riprendersi da una malattia se non sappiamo di essere ammalati -Von Monakow (1885): anosognosia per la cecità corticale -Anton (1893, 1899): anosognosia per la plegia, emisomatoagnosia e anosognosia per la cecità corticale - Pick (1899): emiplegia, emianopsia e dislessia da neglect; negava tutti i disordini -Zingerle (1913): anosognosia per l’emiplegia i disturbi vengono considerati: disordini locali della coscienza e della rappresentazione mentale -Babinski (1914; 1918) conia il termine ‘anosognosia’. Berti et al., 1998 Berti et al., 1998 An example that illustrates the motor behavior of the anosognosic patient CC. This patient developed left side hemiplegia and anosognosia after a right hemisphere ischemic stroke affecting fronto-parietal areas, sparing SMA. She was well oriented in time and space. Her intellectual abilities were within the normal range for her age and educational level. She did not show any language or memory problems. E=examiner, P=patient. E: Where are we? P: In the hospital E: Why are you in the hospital? P: I fell down and I bumped my right leg E: What about your left arm and leg? Are they all right? P: Neither well nor bad E: In which sense? P: They are aching a bit E: Can you move your left arm? P (remaining completely still): Yes I can. E: Could you clap your hands? P: I am not at the theatre. E: I know. But we just want to see whether you are able to clap your hands. P: (CC lifts her right arm and puts it in the position of clapping, perfectly aligned with the trunk midline. Moving it as if it was clapped against the left hand! She seems perfectly satisfied with the performance). E: Are you sure that you are clapping your hands? We did not hear any sound. P: I never make noise. E: Can you raise both your arms? P: (raising the right arm but not the left) Here you are! E: Have you raised also the left arm? P: Yes E: Thank you. You can now put your arms down. E: Could you clap your hands? P: (the patient raises the right arm and says) Where has it gone? I must go and look for it (presumably speaking of the left hand). It must come back by itself. E: Where is the left hand? E: Now, could you raise your right arm again? (CC does it without any hesitation) P: I do not know. I think that it has gone for a walk. E: Now could you slowly raise your left arm and tell me when it is at the same height as the right? P: (After a few seconds) Done! E: Has it gone by itself, detached from your body? P: Yes. E: Are you sure? P: Yes! E: At this very moment is your left hand away from you? P: Yes. E: Please look on the left and tell me whether or not the left hand is back. P: (looking on the left side) it is back now. E: Can you move it now? P: I do not now. It is too far away to give an answer. Different behaviours Different behaviours When explicitly asked about their motor abilities: Verbal vs Non-verbal: severe denial somatoparaphrenia Anosodiaforia 1. Patients who do not complain of being confined in bed with severe verbal denial 2. Patients who admit their paralysis, but try to get off the bed (and fall) Different degrees of severity or different brain mechanisms? How frequent is AHP? -Pia et al. 2004 between 20% and 50% of right brain damage affected by left hemiplegia a) Studies that reported anosognosia irrespective of the side of the lesion b) Studies that distinguished between right and left brain damaged patients c) Studies that selected only right brain damaged patients. a) Studi che non tengono conto del lato lesionale 60% 28% 20% 31% 66% 32% b) Studi che dividono i pazienti in base alla sede lesionale 51% 39% 58% 62% c) Studi che selezionano i pazienti in base alla presenza di lesione destra 56% 41% 33% 20 44% 26%

Scaricare