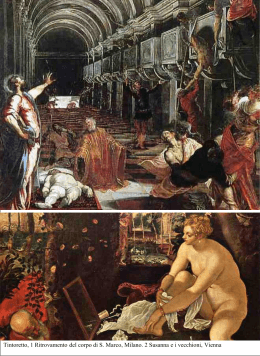

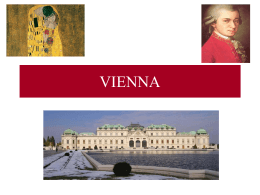

0010.prime_pagine.qxd 22-07-2009 11:31 Pagina 1 fondazione venezia 2000 per fondazione di venezia almanacco della presenza veneziana nel mondo almanac of the venetian presence in the world Marsilio 0010.prime_pagine.qxd 22-07-2009 11:31 Pagina 2 a cura di/edited by Fabio Isman hanno collaborato/texts by Gino Benzoni Sandro Cappelletto Giuseppe De Rita Francesca Del Torre Scheuch Sylvia Ferino-Pagden Fabio Isman Andrea Landolfi Rosella Lauber si ringraziano/thanks to Christian Beaufort Annalisa Bini Augusto Gentili Giorgio Manacorda Stefania Mason Giorgio Tagliaferro traduzione inglese Lemuel Caution English translation progetto grafico/layout Studio Tapiro, Venezia © 2009 Marsilio Editori® s.p.a. in Venezia isbn 88-317-9916 www.marsilioeditori.it In copertina: Andrea Appiani, jr., Venezia che spera, particolare, ante 1861, Milano, Museo del Risorgimento Front cover: Andrea Appiani Jr, Venice Hoping, detail, before 1861, Milan, Museo del Risorgimento 0010.prime_pagine.qxd 22-07-2009 11:31 Pagina 3 sommario/contents 5 7 9 23 39 55 71 79 89 99 111 121 133 147 161 177 Dalla rimozione e il rancore alla riscoperta del grande patrimonio comune From repression and resentment to the re-discovery of a great common heritage Giuseppe De Rita Da Venezia fino a Vienna, andata e ritorno: per chi suona la campana? From Venice to Vienna and back again: for whom does the bell toll? Gino Benzoni Tra ambasciatori e spie, artisti e musicisti, secoli di rapporti in cagnesco Ambassadors and spies, artist and musicians: centuries of perilous relations Fabio Isman La laguna come un’alterità a portata di mano, e poi il mito della città morta The lagoon as proximate alterity. And the myth of the dead city Andrea Landolfi Un acquisto dietro l’altro, nasce la più ricca e documentata raccolta veneziana all’estero One purchase after another leads to richest and most documented venetian collection abroad Sylvia Ferino Pagden Dalla laguna fino agli Asburgo: i tanti viaggi di un ciclo di 12 Bassano (ma uno è sparito) From Venice to the Habsburgs: the many voyages of a cycle of 12 Bassanos (but one is missing) Francesca Del Torre Scheuch Nello stesso anno, il 1787, due Don Giovanni: però quanto diversi tra loro Two Don Giovannis in the same year, but so very different Sandro Cappelletto «Vendere a ogni costo»: spariscono 5000 dipinti, ma tornano cavalli e leone “Sell, whatever it costs”: 5000 paintings disappear, while horses and lion return to Venice Rosella Lauber 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 4 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 5 la città dell’imperatore e quella del doge dalla rimozione e il rancore alla riscoperta del grande patrimonio comune Giuseppe De Rita 1. Andrea Appiani jr., Venezia che spera, ante 1861, Milano, Museo del Risorgimento. Andrea Appiani Jr, Venice Hoping, before 1861, Milan, Museo del Risorgimento. l’editoriale 0020.saggi.qxd Y Noi di «Venezia Altrove» siamo andati un po’ in tutto il mondo a ricercare le tracce della produzione artistica veneziana. Ma per anni, ci siamo astenuti di andare a Vienna, pur sapendo quanto strettamente le due città, le due culture, abbiano vissuto insieme. Y I maligni potrebbero dire che l’abbiamo fatto per rimozione. Chiunque senta intensamente Venezia sa infatti che Vienna, vista dalla laguna, non è un luogo, ma è il simbolo di un dominio. Un dominio che ha azzerato una lunga storia politica e civile, ma ha anche distrutto una costante libertà di espressione e di produzione culturale. Venezia era in lunga e inarrestabile decadenza quando arrivarono gli austriaci, e quella decadenza connota ancora lo spirito della città; ma la cesura fu troppo traumatica, segnò davvero la fine di un mondo. Ed è comprensibile che i veneziani, magari coltivando un facile alibi, abbiano vissuto con silenzioso rancore questi ultimi due secoli di un potere diverso, divenuti poi con il tempo marginalità storica e civile. Confessiamolo: rimuovere Vienna è stato per i veneziani quasi indispensabile per continuare a vivere, in una mediocrità appena appena compensata dalle gloriose serenissime memorie. Y Ma era giusto superare la rimozione e recuperare l’insieme di tanti rapporti intrattenuti a lungo fra artisti, musici, mercanti, viaggiatori e letterati di Vienna e di Venezia. Chi leggerà le pagine che seguono sarà, speriamo, portato a superare i rimpianti e i rancori. E si renderà conto che i tanti rapporti hanno creato un patrimonio comune: un patrimonio che non è più da leggere con le lenti del contrasto fra dominanti, ma con la gioia di un dono misteriosamente consegnato a tutti noi. 5 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 6 the city of the emperor and the city of the doge 0020.saggi.qxd 2. Di artigiano ignoto, la polena della pirofregata austriaca La Bellona, varata a Venezia nel 1827, e Antonio Canova, Ebe (1816-1817), Forlì, Pinacoteca civica. 6 By unknown craftsman, the figurehead for the Austrian frigate La Bellona, launched in Venice in 1827, and Antonio Canova, Hebe (1816-17), Forlì, Pinacoteca Civica. 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 7 the city of the emperor and the city of the doge from repression and resentment to the re-discovery of a great common heritage editorial 0020.saggi.qxd Giuseppe De Rita Y VeneziAltrove has travelled the world in its search for traces of Venetian artistic production. But for years we have put off going to Vienna, even though we knew just how close the two cities and cultures have been. Y Those given to maliciousness might say this was due to a case of Freudian repression. Anyone who feels deeply for Venice, in fact, knows that Vienna, seen from Venice, is not so much simply a place as the symbol of supremacy and rule. A supremacy that brought to a close a long period of political and civil history, and that also brought to a close a long tradition of freedom of expression and cultural production. Venice had for a long while been inexorably in decline when the Austrians arrived, and that decadence continues to connote the city’s spirit. But at that time the caesura was too traumatic, and signalled the veritable end of a world. It is comprehensible that the Venetians, perhaps latching onto a facile alibi, experienced with silent resentment these two centuries under a different power, gradually becoming historically and civilly marginal. Let’s admit it: the “repression” of Vienna, for Venetians, has been virtually indispensable, allowing them to continue to live in a mediocrity only just compensated by memories of the glorious Serenissima. Y But it was important to go beyond this repression and recover that set of myriad relations between Venetian and Viennese artists, musicians, merchants, travellers and men of letters. Anyone who reads the following pages will, it is to be hoped, be tempted to leave regret and resentment behind. And they will realise that the many relations have created a common heritage: a heritage that must no longer be read through lenses highlighting the conflict between two dominant forces, but the joy of a gift that has mysteriously been given to us all. 7 0020.saggi.qxd 8 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 8 1. Josef Carl Berthold Püttner, La fregata austroungarica “Novara” nel bacino di San Marco, particolare, Vienna, Heeresgeschichtliches Museum; il dipinto è successivo al 1862. Josef Carl Berthold Püttner, The Austro-Hungarian Frigate “Novara” in St Mark’s Basin (detail), Vienna, Heeresgeschichtliches Museum; painting is post1862. 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 9 quattro secoli di rapporti tra confronti, rivalità, sospiri da venezia fino a vienna andata e ritorno: per chi suona la campana? la storia 0020.saggi.qxd Gino Benzoni Y «Piacenza non è Singapore»; così, con inoppugnabile inizio, Giorgio Manganelli a connotare da subito la prima città. Venezia non è Vienna, possiamo dire a nostra volta, Vienna non è Venezia. E potremmo a questo punto fermarci. Se, invece, proseguiamo, soccorrevole al procedere quanto osserva, reduce da Mosca nella natia Berlino, Walter Benjamin. «È Berlino che si impara a conoscere attraverso Mosca»; al rientro da questa, quella gli «si mostra come lavata di fresco». Nel rivederla, gli par di vederla per la prima volta, come sorpreso dalla ventata di una novità scompaginante le abitudini del consueto, sommovente le sicurezze dell’assuefazione. «Eppur c’è chi vive e lavora a Macerata»: così, non senza perfidia, Ennio Flaiano. Ma non è, tuttavia, da escludere che anche al bancario maceratese sia data – al rientro, che so?, dalle Maldive – l’esaltante sensazione della riscoperta con occhi nuovi. Col che è al ritorno che si distruppa dal torpore generalizzato del turismo organizzato, che si smarca dal troppo tempo trascorso nell’obbedienza irreggimentata degli aeroporti dove, nelle ore d’attesa della partenza, la meta perde ogni sapore di destino. Y «Andare a Mosca. Vendere tutto qui, casa, tutto, e via, a Mosca!». Questo l’impulso d’Irene. D’accordo sua sorella Olga: «Sì, a Mosca, via, via!». Soffocante nelle Tre sorelle cechoviane la provincia. E miraggio calamitante Mosca per chi, in un qualche remoto governatorato della Russia 1900, si sente in questo avvizzire. Ma miraggio nella società moscovita nel contempo Parigi. È questa la ville lumière per antonomasia. A Parigi, a Parigi allora. È dal Settecento che così ci si propone, che, quanto meno, così si sospira. Ma avvertibili analoghi propositi, analoghi sospiri indirizzati ben prima – già lungo il Quattrocento – alla volta di Venezia. A Venezia, a Venezia! Nel paesaggio mentale europeo s’impone quale colei che più significa, che più promette, che si offre quanto ovunque si desidera e però altrove non c’è. Unica e irriproducibile la sua bellezza urbanistico-architettonica a visua- 9 22-07-2009 quattro secoli di rapporti tra confronti, rivalità, sospiri 0020.saggi.qxd 2. Intagliatore del xvi secolo, Venezia come Giustizia, Venezia, Museo storico navale. 16th-century engraver, Venice as Justice, Venice, Museo Storico Navale. 10 11:27 Pagina 10 lizzare l’intima bontà della sua costituzione nell’assurgere – specie cinquecentesco – a «vera immagine» di perfetta repubblica, di perfetto governo, di perfetta città-stato (fig. 2). Y È una martellante autodicitura confortata da riconoscimenti esterni, e, talvolta, sin anticipata. È autoconvinzione della classe dirigente marciana che a Palazzo Ducale – sede del comando, centro elaborativo e direttivo della Serenissima – si autogratifica con l’illustrazione degli episodi più importanti della propria storia e la rappresentazione allegorica dell’idea di sé nella storia, per la storia. Rovinosi, per Palazzo Ducale, gli incendi dell’11 maggio 1574 e del 20 dicembre 1577. Ma subito precettati i migliori pennelli – ossia Veronese, Tintoretto, Palma il Giovane – a dir nuovamente e meglio di quanto del già detto con figure è stato distrutto dalle fiamme che Venezia è vincente, giusta, elargitrice di felicità ai sudditi e sinanco, con la grandiosa tela del Paradiso tintorettiano (fig. 3), riecheggiamento del regno celeste, quasi suo anticipante preannuncio terreno, suo abbozzo preconfigurante: con il piovere su di lei la privilegiante luce dall’alto, la fa lievitare quasi smaterializzandola, quasi alleggerendola dai grevi condizionamenti terrestri perché, discatenata dal contingente e dal caduco, proiettata nell’eternità, possa verso questa spiccare il volo. Y Tra mare e cielo, di quello signora è verso questo protesa. Non «sicut aliae civitates» la città di San Marco, che – effettivo terminal lungo il medioevo del pio pellegrinaggio al Santo Sepolcro affidato a una vera e propria navigazione di linea che a lei fa capo, da lei organizzata – si trasfigura ad allusione della Gerusalemme celeste; tant’è che, negli incensamenti turibolanti, il Senato, il Maggior Consiglio diventano angeliche gerarchie d’un governo che – in un mondo squassato dall’ingiustizia, dalla violenza, funestato dal malgoverno – in certo qual modo, come sintonizzato col regno dei cieli, l’attesta. Unico titolare della pietra filosofale del buon governo il patriziato lagunare, e come tale quasi delegato in terra a rammentare, aristocratico governo dell’utopia realizzata, anzi dell’attingibile eutopia, la liceità della speranza, a suscitare effettive speranze. 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 11 Y Sin patria dell’anima, nel Cinquecento, la Venezia del mito, la città mitogena. A encefalogramma piatto, nel confronto, la coeva Roma dei papi, nei rapporti con la quale la Serenissima, persuasa d’essere l’ottimo e il migliore dei reggimenti terrestri, non cela sensi di superiorità; donde la fierezza con cui presidia le proprie prerogative giurisdizionali di contro alle pretese invadenti e ingerenti della città di San Pietro (fig. 4). E quasi oscurata questa da un protagonismo a dir del quale Venezia – al di sopra di «tutte le altre» città passate e presenti, «così antiche come moderne» – «drittamente», a pieno titolo, «può chiamarsi metropoli dell’universo», culmine dell’eccellenza umana. Y Avvertibile una simile presunzione anche nei diplomatici veneziani: allorché all’estero, ci si sentono rappresentanti d’una città-stato in cui la mediocritas s’è sublimata ad aurea mediocritas. Sempre implicitamente e spesso esplicitamente nutriti d’orgoglio civico gli ambasciatori d’una Venezia fatta di splendor civitatis e sapienza di governo. Se quella, Venezia, è il costante metro di misura della sua diplomazia, ne consegue che questa – nel caso di Vienna – al più è disposta a riconoscere che il campanile di Santo Stefano è alto, all’incirca, quanto quello di San Marco. Ma suscita sorrisi di compatimento l’arsenale, un “luogo” sul Danubio «serrato di legnami», che, anche nei suoi momenti di più intensa attività, resta irrilevante se considerato con ottica veneziana (fig. 5). Ma non così Vienna, se valutata nella sua storica funzione di Kaiserstadt che dai 20 mila abitanti del 1500 passa ai 100 mila del 1683 – che, però, sono sempre meno di quelli di Venezia (demograficamente seconda in Italia, preceduta solo da Napoli), la quale nel 1500 ha almeno 100 mila abitanti, e nel 1683 almeno 140 mila – per poi svettare coi 325 mila conteggiati nel 1790 (fig. 6). E, a questo punto, di gran lunga distanziata Venezia, che, quell’anno, non raggiunge i 140 mila abitanti. Y Certo che Venezia, insulare com’è, più che tanto non può crescere. Ristretto lo spazio fisico. E dentro questo, costipata la popolazione. La quale, toccato l’apice dei 170 mila abitanti nel 1575, cala falcidiata dalla peste che proprio quell’anno piomba sulla città; e cala vieppiù dopo la successiva peste del 1630. Ciò non toglie che, anche se oggettivamente impossibilitata a competere in termini di crescente sviluppo urbano, la città non possa aspirare ad altri primati. E con l’impianto cinquecentesco d’una rete di rappresentanza stabile presso le capitali europee e il Turco, destinata a durare e pure ad allargarsi sino alla caduta della la storia 0020.saggi.qxd 11 quattro secoli di rapporti tra confronti, rivalità, sospiri 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 3. Il Paradiso di Jacopo Robusti, detto il Tintoretto: dopo l’incendio del 1577, domina la Sala del Maggior Consiglio nel Palazzo Ducale di Venezia. Jacopo Robusti, known as Tintoretto, Paradise. After the fire of 1577, it dominates the Sala del Maggior Consiglio, Venice, Ducal Palace. 12 11:27 Pagina 12 Serenissima, in effetti primeggia quale colei che più sistematicamente e continuatamente osserva. Tant’è che viene definita «occhio del mondo» sia perché questo – il mondo – ha in lei il proprio organo visivo, sia perché quest’ultimo si fa sguardo sul mondo. Città specola, dunque, Venezia, alla quale arriva il massimo dell’informazione – indicativo che, ancorché non protagonista nell’età delle scoperte, sia quella che più sappia dello scoperto: quella che per prima sia in grado di registrarlo cartograficamente – per poi essere ridistribuito sì che si diffonda. E addetti allo sguardo intendente gli ambasciatori veneti, espressione dello stato marciano che, per loro tramite, prende le misure degli altri stati, li valuta nel loro peso specifico e in quello relativo, non senza, implicitamente, autovalutarsi ed autosoppesarsi. Tenuti i rappresentanti della Serenissima a Vienna – o a Praga quando è qui l’imperatore – al profilo della corte e dei suoi protagonisti, al ritratto degli imperatori e dei principali ministri, alla considerazione, nell’arco di tempo che va dall’assedio del 1529 a quello del 1683, della tenuta o meno della città quale «bastione» antiottomano, quale «propugnacolo» della cristianità tutta contro l’irrompere del Turco. Y Gran «machina» l’impero; ma come funziona? Sulla carta, l’imperatore detiene il «primo posto» nella gerarchia dell’intera umanità. Però tanta primazia è più «apparenza» che «sostanza»: lungi dall’esplicarsi «assolutamente», imperiosamente l’«autorità imperiale» è condizionata dalle Diete, anche revocata e disdetta, talvolta disobbedita e vilipesa. Una risultanza che la diplomazia lagunare accentua mano a mano che constata il simultaneo dispiegato e incondizionato comando da Luigi xiv, il cui spadroneggiare in casa si coniuga con una politica estera espansiva nel trionfo della quale Venezia è costretta ad avvertire tutta la precarietà della propria subalternanza. Impotente di fronte a tanta potenza il vessillo – ormai sgualcito e sdrucito – del mito del buon governo, che, non a caso, Nicolas Amelot de la Houssaye, un segretario dell’ambasciata francese a Venezia, demolisce senza riguardi nell’Histoire du gouvernement de Venise (Paris 1676-1677), un longseller che varrà a screditare la ormai vecchia Repubblica anche nel secolo successivo. Y Vanamente Marco Foscarini, doge nel 1762-1763, s’affannerà a riesumare in Della letteratura veneziana (Padova 1752) la cinquecentesca sapienza civile marciana, a rianimare il settecentesco declino. Più che il recupero del passato glorioso, servirebbero – 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 13 questa la convinzione degli stessi membri più pensosi del governo veneto – delle grandi riforme, un autorinnovamento radicale. Ma questo dovrebbe scalzare lo stesso governo patrizio, lo stesso sistema Venezia collaudato nei secoli, ma anche logorato dai secoli. E nemmeno i patrizi più spruzzati di lumi, che a Venezia non mancano, a ciò sono disposti. Intanto, grande l’impressione su Palazzo Ducale del “dispotismo” illuminato di Giuseppe ii (fig. 7), che, a Vienna e da Vienna, d’un tratto, a suon di perentori decreti, con una raffica di ingiunzioni su tutto il territorio imperiale, vorrebbe imporre a questo l’omologazione di un’uniformante razionalizzazione per sopprimere specificità e differenze delle «varie nazioni» costrette a «un sol corpo ben compatto e solido». Solo che – riferisce l’ambasciatore a Vienna Daniele Dolfin – siffatto «vasto edifizio» programmato a tavolino quale geometrica architettura totale, quale disciplinamento globale di una sudditanza tutta allineata, messa al passo, fatta marciare all’unisono, «crollò» non appena allestito per il dilagare del «malcontento» nelle periferie, per la riottosa e sin rivoltosa riluttanza delle «provincie». Nel constatare tale rapido collasso, nel diagnosticare il tracollo della gigantesca riforma c’è, da parte di Palazzo Ducale, una sorta di brivido di compiacimento. Accusato dalla cultura illuministica, dai governi riformati, di torpore incapace di riforme il governo veneto. Ma è una colpa non saper riformare con il piglio decisionistico di Giuseppe ii? Oppure continua a valere la multisecolare saggezza ispirante ancora la classe dirigente marciana che, fedele a se stessa, ha conservato il sembiante dello stato consegnato dal passato, ha mantenuto le corporazioni, ha rispettato le consuetudini locali, gli statuti locali, le locali varietà, le locali differenze? Che siffatta conservazione non sia una valida lezione di ammonente saggezza di contro al disastro del giuseppinismo omologante, di contro alle furie dell’accentramento giacobino? la storia 0020.saggi.qxd 13 quattro secoli di rapporti tra confronti, rivalità, sospiri 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 4. Francesco Guardi, Pio VI prende congedo dal doge nel convento di San Zanipolo, 1782, Milano, collezione privata. Francesco Guardi, Pope Pius VI Blessing the People on Campo Santi Giovanni e Paolo, 1782, Milan, private collection. 14 11:27 Pagina 14 Y Ma chi è disposto a prestare orecchie ricettive al savio magistero che può provenire da Venezia quando, nel 1797, con la spallata napoleonica prima crolla la Serenissima e poi sparisce dalla carta geopolitica europea ogni parvenza di stato veneto indipendente (figg. 8, 9)? Città ex, a questo punto, Venezia: ex stato, ex capitale. E solo città sotto, a questo punto, quella marciana, specie sotto l’Austria, specie sotto Vienna e, in via subordinata, sotto Milano. Non più la Dominante ora la città lagunare, ma città suddita (figg. 1, 10), città per forza di cose soggetta, sottoposta e, in certo qual modo postuma, il cui trascorso protagonismo di secoli è testimoniato dalla sterminata documentazione serbata nei depositi dell’Archivio dei Frari memorizzanti i tempi del comando statale, del dominio in terra e mare all’insegna dell’evangelista Marco. Lì, con il costituirsi ottocentesco nella Venezia dopo di quello, dell’archivio, la ragionata archiviazione in chilometri e chilometri di scaffalature della carte della Venezia prima. Perseguibili e di fatto perseguiti grazie al salvataggio archivistico gli studi su questa, quella di prima. Y Ciò non toglie che, nella percezione della coscienza europea, quella che vive dopo, non tanto sia intesa come colei che, studiosa nell’Archivio dei Frari del proprio passato di città-stato, in certo qual modo lo rivive; ma piuttosto come colei, d’un tratto, ha perso la capacità di dirsi: s’è fatta afasica, è ammutolita, come morta. E, nel silenzio della defunta, sono gli altri a dir di lei, a strattonarla con lugubri diciture, quale città necropoli, quale corpo in decomposizione, quale residuato cimiteriale. Venezia è la città della morte (fig. 11), dove si viene per morire, come fa il poeta slesiano Moritz von Strachwitz: divorato dalla tisi, nell’agosto-ottobre del 1847, il morituro si sente – anche se di fatto morrà l’11 di- 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 15 cembre 1847 a Vienna – in piena consonanza col disfarsi dei palazzi corrosi e tarlati che s’affacciano sui canali. E ormai nel primo Novecento, Venezia è la città appestata dove il manniano Aschenbach giunge sfinito: e s’accascia nella spiaggia lidense, mentre svanisce il profilo di Tadzio. Y Ammagati poeti e scrittori dalla Venezia non più – quella di prima, si capisce – vestita a lutto, vedova in gramaglie, fantasmatica, larvale, adoperabile a mo’ di tastiera docile a funerei martellamenti romantici, annusabile a mo’ di malsana serra marcescente ove localizzare situazioni estreme, decadenti, spasimi orgasmatici e spasimi preagonici. Per vivere, vi si arrabatta il nobiluomo Vidal di Giacinto Gallina. Vi conciona e vi si afferma in alcova il dannunziano Stelio Effrena. Niente languori romantici, comunque, e niente complicazioni decadenti nelle carte a Vienna prodotte o arrivate, e a Vienna archiviate dall’amministrazione austriaca. Nell’ottica del governo asburgico, Venezia non è la città notturna, sfibrata, sfasciume piranesiano galleggiante in acque ormai prossime a inghiottirlo (fig. 12). È viva, sin vivace, sin temibile per l’attecchirvi d’idealità risorgimentali. E antiaustriaco, antiviennese il biennio rivoluzionario del 18481849. Spento sì il suo incendio dal governo di Vienna, ma ardua la ripresa del controllo. Comunque, nelle sue tre fasi con altrettante soluzioni di continuità, la Venezia austriaca non è pendula sull’abisso come vorrebbero i poeti, ma è, invece, attiva, reattiva, operosa. E i suoi problemi sono quelli della vita che, bene o male, a volte più male che bene, prosegue; non già quelli della fine imminente: interrare i rii? moltiplicare i ponti? aumentare la pedonalizzazione con relativa diminuzione dei traghetti? Ci pensano gli amministratori locali, vigilati da Milano e da Vienna. E le decisioni grosse passano da quella e da questa. E i comandi vengono da entrambe. Marcata e marchiata la Venezia Ottocento, la Venezia austriaca dalla fine dell’insularità. Ferrovia sì o ferrovia no? Va da sé che, se si opta per il treno, occorre il ponte ferroviario. È con questo che arriva in treno Strachwitz. Ma tutto proteso a finire i propri giorni nella città i cui palazzi si sfarinano sulle acque dei canali che la tramano neri nel nero della notte, è sordo al “ciuff ciuff” della locomotiva, cieco alla folla che ci cammina e ci lavora. Per carità: non è un rimprovero. Anche se la città nel frattempo è viva e prossima a insorgere, la sua ispirazione la vuole morta, solfeggia su questo tasto. Y Annessa, nel 1866, Venezia al Regno d’Italia. E, a questo la storia 0020.saggi.qxd 15 quattro secoli di rapporti tra confronti, rivalità, sospiri 0020.saggi.qxd 16 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 16 punto, silenti su di lei le carte, i rapporti, i rendiconti, gli atti, i protocolli, le relazioni, le scritture viennesi. Non più argomento per i ministeri della Kaiserhof. In compenso, sono gli autori viennesi, o per nascita o, quanto meno, per attività, a guardare a Venezia e anche a portarvicisi. Il treno – come insegna Carducci – i monti supera, divora i piani. A portata di mano Venezia per Vienna. E chiaroscurate entrambe negli accostamenti di Rilke – praghese di nascita e austriaco di formazione: la scuola militare di Sankt Pölten; l’accademia di commercio di Linz; con quella e con questa, il padre aveva tentato d’inchiodarlo a un compito preciso nel quadro dell’impero austroungarico – laddove, a partire dal 1897 con puntate intermittenti, a Venezia tende ad ambientare la propria sensibilità. In questa – scrive nel 1907 alla moglie – «diversamente» che a Vienna, «ci si ritrova tra cose indicibili». Rilke sta allora scrivendo I quaderni di Malte Laurids Brigge, il quale, ancor bambino, intuisce confusamente che «la vita sarebbe stata», per lui, «piena di cose strane» e, appunto, «indicibili», pressoché a tutti precluse e, al più, intendibili da «uno soltanto». Costui è proprio Malte, che l’indicibile l’incontrerà a Venezia quando – stralciandosi dal turismo intontito dal dondolio delle gondole che introduce alla fruizione d’una Venezia «molle e oppiacea» – è come trafitto dalla visione della Venezia autentica, «vera», non banalizzata dal consumo turistico. Non dolci baci e languide carezze e belle forme disciolte dai veli al chiaror di luna e/o in albergo, non notturni roventi amplessi di coppie legittime in viaggio di nozze, o di amanti più o meno clandestini, più o meno adulterini. Ma una città «mattutina», energica, volitiva, «voluta in mezzo al nulla», «arsenale insonne», che nella storia irrompe come «esempio di volontà austero ed esigente». Fulminato, al pari di Malte, da questa Venezia, in una lirica del 1907-1908 Rilke l’avverte salire «dal fondo», «da antichi scheletri di foreste» con l’indomita volontà leonina 22-07-2009 5. Gianmaria Maffioletti, L’Arsenale al momento dell’arrivo delle truppe austriache, datato 1798, Venezia, Museo storico navale. Gianmaria Maffioletti, The Arsenale on the Arrival of the Austrian Troops, dated 1798, Venice, Museo Storico Navale 11:27 Pagina 17 impersonata dalla flotta che, con il favor della «brezza», appunto, «mattutina», salpa alla volta del mare aperto. Y Catturato, irretito, sedotto da Venezia Rilke – che il padre avrebbe voluto ufficiale dell’imperial esercito; e magari, gli avesse obbedito, avrebbe fatto carriera di guarnigione in guarnigione, con il miraggio d’un trasferimento al viennese ministero della guerra, in tal caso sospirando a Vienna, a Vienna! – non per scivolare nel «puro incantamento», ma per afferrarne «il segreto», per intenderne l’essenza, come dichiara in una lettera del 1912. Y E intanto a Vienna il viennese (fino al midollo: l’infantile sua «camera di Vienna» è, per lui, «il mondo intero») Hugo von Hofmannsthal continua ad arrovellarsi su argomenti veneziani come ha già fatto con un frammento teatrale sulla morte di Tiziano, con la tragedia La Venezia salvata, con il racconto La lettera dell’ultimo Contarin. Inizia, all’incirca nel 1912, da parte di Hofmannsthal, la faticata e protratta e non ultimata stesura di un romanzo, il cui titolo iniziale oscillante tra Diario del viaggio veneziano del signor N. e L’avventura veneziana del signor N. troverà alfine la sua sistemazione in quello, più enigmatico ma anche più indicativo del contenuto – c’è di mezzo la tensione al superamento della lacerazione tra eticità ed esteticità, al ricongiungimento di quanto è divaricato, alla ricomposizione di ciò che divide –, di Andrea o i ricongiunti, con il quale uscirà postumo quale Fragment, spezzone d’una narrazione troncata di brutto, non conclusa, sconclusa. Y D’altronde come chiudere quando le chiusure praticabili virtualmente si moltiplicano? Ad ogni modo, il protagonista è Andrea, che dalla Vienna 1778 – in questa l’imperatrice Maria Teresa (fig. 13) con il suo moderato, ben temperato riformismo, mentre il figlio Giuseppe, il futuro imperatore, sta scalpitando bramoso di vieppiù riformare – muove alla volta di Venezia. «Troppo angusta» per il giovane Andrea, troppo semplice, troppo univoca la capitale imperiale per rispondere ai propri assillanti interrogativi. Spera che la risposta possa venirgli da e a Venezia, quasi solo qui sia dato di «cercare» sino «in fondo alle cose». Di fatto, arriva in una città stralunata, notturna, mascherata. La ricerca diventa «avventura»: frastornante, occultante, sviante la ridda delle apparenze, ma anche illuminante, rivelante nella misura in cui non è da escludere la profondità stia nella superficie, la verità coincida con l’ambiguità della maschera, lo scavo più autentico per ritrovare se stessi, lungi dal risolversi la storia 0020.saggi.qxd 17 quattro secoli di rapporti tra confronti, rivalità, sospiri 0020.saggi.qxd 18 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 18 nello «scendere nella nostra interiorità», consista, invece, nell’abbandono all’ondivago e contraddittorio gironzolio delle circostanze più dispersive. E, allora, non concentrazione con presunzione di coerenza, ma disponibilità duttile e flessibile. Non autoauscultazione procedendo dentro, ma errabondo tentativo di trovarsi fuori. A Venezia, a Venezia, nel fuori più fuori. Solo che a Venezia Andrea non si ricompatta: si scheggia, si smarrisce. Se, nell’andarvi, ha incontrato, in una valle, una ragazza dal cuore intero, ha assaggiato la vita semplice e genuina d’una montana fattoria, ecco che a Venezia Andrea si sdoppia nell’incontro divaricante con una giovane dama e un’avvenente cortigiana. Spiritualità rarefatta la prima, sensualità torrida e disinibita la seconda. Così a tutta prima. Ma sino a un certo punto. C’è un che di inquietudine repressa nella contegnosità della prima. E sin inquietante la carnalità della seconda. E torbida la situazione laddove questa vorrebbe Andrea seduttore della prima. Lasci perdere – l’esorta scaltra – l’ossessione della «verità»; non è che una «stupida parola». Y Certo che, prima o dopo e, ormai più dopo che prima, Andrea dovrebbe tornare a Vienna a far qualcosa di concreto. Ma come accingersi a «il viaggio del ritorno», quando, con sgomento, avverte di non poter «assolutamente ritornare alla limitata esistenza di Vienna»? Perplesso il giovane sul da farsi; e perplesso anche l’autore sul che fargli fare. Di per sé, appena arrivato a Venezia – in questa sbarcato sul far dell’alba, scaricato di brutto da un brusco barcaiolo, in una sperduta fondamenta dove non passava «un cane» – il giovane ha avuto la ventura d’essere agevolato ad ambientarsi dalla cortesia soccorrevole d’un uomo mascherato, sbucato provvidenziale da una calle. A tutta prima smarrito e incapace d’orientamento nella città deserta ha nel cavalier Sagramozo, o Sacramozo – questa l’identità della maschera; epperò l’identità consiste anche nell’automascheramento – un mentore eccezionale, una sorta di Virgilio. È personalità non comune, anzi straordinaria. Se vive a Venezia, «fusione dell’antichità e dell’oriente», è perché v’è impossibile ricadere «nel futile e nel meschino», è perché meglio che altrove vi si può essere mondani e, insieme, meditabondi, conferire all’esistenza qualche significanza, una marcia in più. Un maestro per Andrea, ansioso di maturare quest’uomo che aborre l’univocità, padroneggia la complessità e par capace di ricongiungere il disgiunto. Solo che volontariamente si dà la morte. Un suicidio 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 19 filosofico il suo; ma, per Andrea, un tremendo dolore, una perdita irreparabile; smarrito, si sente orfano. Y Di poco successivo all’avvio della tormentata e incompiuta stesura del romanzo di Hofmannsthal l’immergersi, da parte del viennese Schnitzler, nel novembre 1914-febbraio 1915, nella lettura delle memorie casanoviane. Una lettura operativa esitante, nell’ottobre del 1917, in una commedia in versi – qui un Casanova a 32 anni tutto voglia di vivere, tutto arraffante energia seduttiva – e in un racconto lungo, o romanzo breve, nel quale l’avventuriero veneziano è ancora protagonista. Solo che ha perso ogni smalto. Di anni ne ha 53. Non sono pochi. E per di più, li porta male. Ne mostra di più. È arrugginito, acciaccato, incupito, appesantito; con qualche residua pretesa nel vestire, male assecondato dall’abito già elegante, ma ora logoro, sdrucito, rabberciato alla meglio per durare un altro po’. Senza soldi, il guardaroba non può rinnovarlo. Capitato a Mantova, s’ostina a frequentare per brillarvi quel po’ di società che in quel centro di provincia può radunarsi. Sfodera, per far colpo sulla fresca avvenenza di Marcolina, tutti gli artifici della sua conversazione un tempo efficace, un tempo apprezzata e richiesta. Ma adesso, è come muffita, rancida e, peggio, noiosa. Infatti Marcolina s’annoia; e, urtata dalla pretesa di sedurla con questa, non cela il suo disprezzo: gli fa sentire tutto il vecchiume della sua forbita loquela, la sgonfia con pungente sarcasmo. Y Cocente umiliazione per l’avventuriero in là con gli anni l’essere costretto alla consapevolezza che, già macchina seduttiva funzionante a pieno regime nella sinergia di prestanza fisica e disinvolta parlantina, è ormai un ferro vecchio da rottamare: anchilosato il corpo, goffo nei movimenti; imbolsito il volto; polverosa, farraginosa la conversazione. Ha perso ogni fascino. Non incanta più nessuna. Quanto a Marcolina, egli la disgusta. Le fa sin ribrezzo. Ma non si rassegna a ritirarsi in buon ordine. Lo smacco non è un momentaneo incidente; segnala la fine d’ogni velleità di successo per un Casanova che la propria identità l’ha confezionata in termini di grande seduttore, d’irresistibile conquistatore. Ebbene: pur sempre animale di rapina, per sempre rapace, Marcolina la conquisterà con l’inganno, il più infame, il più turpe. Essa ha un amante, un giovane avvenente ufficiale. È con costui che Casanova s’accorda. Nella sua incattivita senescenza, l’avventuriero sa tirar fuori il peggio di sé e il peggio degli altri. Il vecchiaccio malvissuto e il giovinastro cialtrone la storia 0020.saggi.qxd 19 quattro secoli di rapporti tra confronti, rivalità, sospiri 0020.saggi.qxd 20 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 20 sembrano fatti per incontrarsi: quasi per valorizzarsi a vicenda entrambi attestati sulla rapacità che li accomuna. Casanova – che ha vinto al gioco duemila ducati – li gira al giovane che, invece, al gioco ha perso. E questi, in cambio, si fa complice del suo truffaldino intrufolarsi nel letto, altrimenti inaccessibile, di Marcolina. Gli presta il proprio mantello, avvolto nel quale, col quale camuffato, nottetempo, nel buio più pesto, Casanova è accolto dalla giovane nella sua stanza. Scambiato per l’amante, ha modo di scatenarsi con tutta la vigoria superstite dell’instancabile amatore appassionatamente corrisposto da Marcolina. Ma al primo chiaror dell’alba, costei, con «indicibile orrore», ravvisa l’identità di Casanova, e dietro a questa, la laida complicità del giovane da lei amato. S’accorge che non con questo, ma con quello ha trascorsa focosa la notte. Y Insopportabile quell’«orrore» per Casanova. Da quello impregnato, con addosso lo schifo che prova per lui Marcolina da lui insozzata, con addosso il marchio indelebile della sua ripugnanza, Casanova scappa a rotta di collo. Ma gli sbarra la fuga l’amante di quella; non che si sia di per sé pentito: solo che odia troppo Casanova e odia se stesso per essersi con lui accordato. I due sono della «stessa pasta», quasi intercambiabili: Casanova vede nel rivale se stesso da giovane; questi intuisce in quello ciò che diventerà invecchiando. Perciò si detestano a vicenda. All’ultimo sangue il duello. È come lo sdoppiarsi nell’odio di un’unica esistenza somma di giovinezza ribalda e senescenza incarognita. Per tal verso la furia omicida che li avventa l’un contro l’altro ha, in certo qual modo, valenza suicida. Nella distruzione dell’altro, una volontà d’autodistruzione. Casanova ha la meglio: colpisce al cuore con una stoccata il giovane. E, mentre questi giace esamine, fugge senza sosta sino a Venezia, a rintanarvisi impunito. Vi riprende, stanziando al caffè Quadri, lo squallido lavoro di spione prezzolato dagli inquisitori d’uno stato che, ormai intimamente tarlato, paventa sin le chiacchiere degli avventori dei ritrovi. A notte fonda, il Quadri chiude. Nessun più vi bisbiglia. E Casanova non ha di che origliare. Anch’egli può andarsene. Attraversa piazza San Marco «deserta», «oppressa» dall’incombere di un cielo caliginoso, greve senza che traluca una stella. Per calli e callette, con saliscendi di «ponticelli» sotto i quali scorre una lutulenta acqua nerastra come sospinta al ricongiungimento con stigie «acque eterne», l’avventuriero guadagna il miserando alberguccio ove, in una camera disadorna, 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 21 la storia 0020.saggi.qxd 6. Johan Adam Denselbach, Veduta di Vienna dalla Roten Turmtor, 1740, Vienna, Museum Karlsplatz. Johan Adam Denselbach, Scene of Vienna from the Roten Turmtor, 1740, Vienna, Museum Karsplatz l’attende un «cattivo» letto, sul quale, stremato da una «stanchezza dolorosa», si butta. Pietoso, sull’albeggiare, il «sonno agognato», «senza sogni», l’inghiotte quasi speranzoso di non risvegliarsi, di non doversi più guardare allo specchio con il medesimo «orrore» con cui l’ha guardato Marcolina. Y Una Venezia 1778 quella in cui Andrea s’illude di riannodare l’io scisso, quella in cui l’attempato Casanova s’accuccia come un animale ferito a morte. Addosso ha l’onore e l’onere d’una storia più che millenaria della quale appesantita non ce la fa a star diritta; e procede con passo incerto, quasi barcollante. Non le resta molto da vivere. Il 12 maggio 1797 s’autodimetterà il Maggior Consiglio e con lui l’intero regime; subentra la Municipalità provvisoria, spazzata via, il 17 ottobre, a Campoformio. Complici lì Napoleone e l’imperatore Francesco i nel far fuori l’autonomia statuale di Venezia, nello spartirsi le spoglie dello stato cancellato di comune accordo. È la fine. E c’è la data. Fissabile sempre questa per la morte. Senza data precisa, invece, il posizionarsi di un mondo verso la fine. E magari un mondo può essere verso la fine e non saperlo, ignorarlo. Ignara la Vienna 1913, che s’accinge ad avviare i preparativi del festeggiamento alla grande dell’ormai non più lontano 1918, quando scade il settantennio del regno del longevo imperatore Francesco Giuseppe. Si forma un comitato per le onoranze; e segretario, si ricorderà, il musiliano uomo senza qualità. Proposito del Comitato esaltare i pregi di Cacania, valorizzare il senso della sua presenza 21 quattro secoli di rapporti tra confronti, rivalità, sospiri 0020.saggi.qxd 22 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 22 storica. Ma – si sa – la prima guerra mondiale farà crollare Cacania. E Vienna, sua capitale, si ritroverà ad essere come un gran testone d’un corpo ridotto a moncherino. Finis Austriae. Va da sé che il tracollo si colloca nel 1918 (fig. 14); ma quando inizia la percezione che un mondo sta per finire? Nel caso di Hofmannsthal e di Schnitzler vivono quel tanto che basta a conoscere sia la Vienna della belle époque, sia quella dopo, travolta dalla sconfitta. E avvertibili nella prima i preannunci di smottamento, di scollamento, di frana. È comunque respirando nella dimensione della fine che i due inventano storie veneziane, ambientate in una Venezia che – essi, con la scienza del poi, lo sanno bene – ha ancora poco da vivere. Scrivono, a Vienna, nei paraggi d’un collasso del mondo in cui sono nati, cresciuti e maturati, di personaggi che, a loro volta, si muovono sul bordo della imminente finis Venetiarum. Vien da dire che le finitudini s’annusano, si fiutano, si cercano, si riconoscono, quasi strofinano l’un l’altra, sin simpatizzano, sin istituiscono affinità elettive. Y D’altronde, se per la Serenissima è suonata la campana, come escludere che il funebre rintocco non possa valere – prima o dopo, magari più dopo che prima – anche per altri, anche per tutti? Trionfante e spadroneggiante l’Inghilterra nel 1816, allorché esce il byroniano Harold’s Pilgrimage. Ma ammonita – un ammonimento rimosso per oltre cento anni, se si considera il tetragono trionfalismo di un Kipling – la superbia della potenza più potente dall’autore: «Nella caduta di Venezia, pensa alla tua». La memoria si fa profezia. Almeno, in Byron, il quale così va oltre la commossa partecipazione al lutto dell’antecedente sonetto di Wordsworth che – meditando sulla vicenda d’una città già «radiosa» per la quale, sfiorita, debilitata, sfinita, senza più «forze», «or è conclusa la sua lunga vita» – a lei offre il «mesto omaggio» del pianto condolente. 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 23 four centuries of relationships – conflict, rivality, hope from venice to vienna and back again: for whom does the bell toll? history 0020.saggi.qxd Gino Benzoni Y “Piacenza is not Singapore”. Thus, incontrovertibly, does Giorgio Manganelli immediately connote the former. Venice is not Vienna, we can say in turn, and Vienna is not Venice. We could even stop there. If, however, we were to continue, then Walter Benjamin, having returned to his native Barlin from Moscow, might come to our assistance. To paraphrase his sentiment, it is through Moscow that one gets to know Berlin; returning from the latter, the former appeared to him anew, as if freshly laundered. On seeing it again, it seemed to him that he was seeing it for the first time, as if surprised by a surge of novelty disrupting usual habit, undermining the security of inurement. Not without a touch of perfidy, Ennio Flaiano had the following to say: “And yet there are people who live and work in Macerata”. But it should nonetheless not be implausible for a bank clerk from Macerata, on his return from, say, the Maldives, to feel the exciting sensation of seeing his city with new eyes. With which it is on his return that he awakes from the generalised torpor inflicted by organised tourism, frees himself from the inordinate amount of time spent in the regimented obedience of airports where, in the hours spent waiting for take-off, the ultimate aim loses all sense of destination. Y “To go away to Moscow. To sell the house, drop everything here, and go to Moscow...” This is Irina’s impulse. And her sister Olga agrees: “Yes! To Moscow, and as soon as possible.” The province, in Chekhov’s Three Sisters, is suffocating. And Moscow is a magnetic mirage for those who, stuck in some remote region in turn-of-the-century Russia, feel stuck in this withering boredom. But the mirage for Muscovite society is, at the same time, Paris. This is the ville lumière par excellence. To Paris, and as soon as possible then. This is the way this has been put forward, or at least sighed, since the 18th century. But there were similar, perceptible aims and similar sighs, throughout the 15th century, directed towards Venice. To Venice, to Venice! In 23 four centuries of relationships – conflict, rivality, hope 0020.saggi.qxd 24 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 24 the European mental landscape, Venice imposes itself as the city that signifies and promises more than any other, that even offers what is desired everywhere, but that can be found nowhere else. Its urban-architectural beauty is unique and un-reproducible, displaying the profound excellence of its constitution in its (mainly 16th-century) rise to “real image” of the perfect republic, government and city-state (fig. 2). Y This is an incessant, selfstyled and, at times, anticipated title, confirmed by nonVenetian acknowledgement. The Venetian powers that be convinced themselves that the Ducal Palace (the Serenissima’s seat of command, its directional and elaborative centre) could best be gratified through illustrations of the most important episodes in its history and the allegorical representation of its idea of itself in history and for history. The fires of May 11, 1574, and December 20, 1577, were disastrous for the Ducal Palace. And the best artists of the period (i.e. Veronese, Tintoretto, Palma the Younger) were brought in to reiterate, and better elaborate, what had already been said through images before being destroyed in the fires, and that is that Venice is victorious and just, bestower of happiness on its subjects and even, via the grandeur of Tintoretto’s Paradise (fig. 3), an imitation of the celestial kingdom, virtually its earthly foretaste, a pre-configuring sketch: with privileging light raining down from above, it is made to hover, almost immaterial now, virtually removing from its shoulders those unbearable earthly conditionings, releasing it from the chains of contingency and the ephemeral, that it might take flight towards this paradise. 22-07-2009 7. Pompeo Batoni, Ritratto dei fratelli Giuseppe II d’Austria e Leopoldo di Toscana, 1770, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Gemäldegalerie. Pompeo Batoni, Emperor Joseph II and His Younger Brother Grand Duke Leopold of Tuscany, 1770, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Gemäldegalerie. 11:27 Pagina 25 Y Caught between sea and heaven, it is the lord of the former and reaching forward to the latter. No sicut aliae civitates the city of St Mark, which, a terminus throughout the Middle Ages for the pious pilgrimage to the Holy Sepulchre handed over to what could only be described as a navigational route headed and organised by the city, is transfigured into an allusion for the celestial Jerusalem; so much so that, in incense-laden adulation, the Senate and Maggior Consiglio became the angelic hierarchies of a government that, violently shaken by injustice and violence and afflicted by misgovernment, in some way, testifies to this very fact. The only bearer of the philosopher’s stone of good government in Venice was the patriciate, and as such they were virtually the earthly reminder, once the aristocratic utopian, or rather the attainable eutopian, government had been realised, of the lawfulness of hope. They inflamed effective hope. Y Venice, in the 16th century, is virtually the home of the soul, the land of myth, a myth-generating city. In comparison to which contemporary papal Rome seemed barely alive. And in Venice’s relationship to Rome, persuaded as Venice was that it commanded the best of land regiments, it could barely suppress a sense of superiority. Hence the pride with which Venice guarded its own jurisdictional prerogatives against the invasive and interfering demands of Rome (fig. 4). Rome is almost obscured by Venice’s desire to be at the centre of attention that made of it – above and beyond “all other cities” past and present, “both ancient and modern” – by rights “the metropolis of the universe”, the apogee of human excellence. The same presumption could be gleaned in Venetian diplomats: while abroad they felt they were representing a city-state where the mediocritas had been sublimated and uplifted to aurea mediocritas. Always implicitly and often explicitly nourished by civic pride, these were ambassadors of a Venice made of splendor civitatis and the wisdom of government. If Venice was the constant yardstick in terms of diplomacy, then it was equally true that Vienna was at most willing to admit that the bell tower of St Stephen’s was approximately as tall as that of St Mark’s. But Vienna’s dockyards, situated along the Danube and “hedged in by timbers”, provoked smiles of pity: even at its most productive, Vienna’s dockyards barely made a mark on Venice’s (fig. 5). But Vienna had its own story to tell. As Kaiserstadt, its inhabitants increased from 20,000 in 1500 to 100,000 in 1683 (the number is still lower than Venice, which, demographically, was Italy’s second history 0020.saggi.qxd 25 four centuries of relationships – conflict, rivality, hope 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 8. e 9. Rudolph Suhrlandt, Ritratto di Antonio Canova, 1811, e Antonio Canova, Maria Luigia d’Asburgo in veste di Concordia (gesso), 1810, conservati entrambi a Possagno, Fondazione Canova: il marmo finito, ora alla Galleria nazionale di Parma, è commissionato da Napoleone, all’indomani delle nozze con la figlia di Francesco i imperatore d’Austria, che posa per l’artista il 13 ottobre 1810 a Fontainebleau. 26 11:27 Pagina 26 most populous city after Naples, and had at least 100,000 inhabitants in 1500 and at least 140,000 in 1683), and then shot to an incredible 325,000 in 1790 (fig. 6). That same year, Venice barely had 140,000. Y Obviously, Venice, insular as it is, cannot grow beyond a certain level. Physical space is very much limited. And within this limited space, the inhabitants were crammed as much as they could be. Venice reached its greatest number of inhabitants (170,000) in 1575, dropping dramatically after the plague of the same year; the population was to take another fall in 1630, after yet another plague. This by no means meant, however, that Venice couldn’t aspire to other records. And with its 16th-century network of stable representation in European capitals and Constantinople, a network that would last and even continue to grow until the fall of the Republic, Venice did indeed excel as the city that most systematically and continuously kept a vigilant eye on all world events. So much so, in fact, that it was defined “the eye of the world”, both because the world had Venice as its eye, and because Venice kept its eye on the world. An observatory-city, therefore, which collected as much information as was humanly possible (indicative of the fact that, although it wasn’t a leading player in the world of discoveries, it certainly was the city that knew most about those discoveries, and was the first city in the world to represent what had been discovered via cartographic representations) so as to leak as much of it as possible. And specialists of the gaze incumbent on Venetian ambassadors, the expression of the Venetian state that, through them, measured other states, evaluating them in their specific and relative weight, not without, implicitly, evaluating and weighing themselves up. The representatives of the Serenissima were held to stay in Vienna (or Prague when the emperor was in Prague), in close touch with the court and its protagonists, the emperor and his main ministers, considering, in the stretch that goes from the siege of 1529 to that of 1683, whether the city 22-07-2009 8 and 9. Rudolph Suhrlandt, Portrait of Antonio Canova, 1811, and Antonio Canova, Maria Louise as Concord (plaster), 1810, both at Possagno, Fondazione Canova: the finished work, now at Parma’s Galleria Nazionale, was commissioned by Napoleon following his marriage to the daugher of Emperor Francis i, who posed for the artist on October 13, 1810, at Fontainebleau. 11:27 Pagina 27 would hold as anti-Ottoman “bastion”, as the plucky little defender of Christianity against Turkish encroachment. The empire was a huge “machine”, and the question was “How does it work?” On paper, the emperor held the highest post in the hierarchy of all humanity. But all this primacy was more “appearance” than “substance”: far from finding expression “absolutely” and imperiously, this “imperial authority” was conditioned, even revoked or cancelled, sometimes disobeyed and reviled, by the “Diets”. An outcome that Venetian diplomacy accentuated as it gradually observed the simultaneous deployment and unconditional command by Louis xiv, whose domestic domineering combined with an expansive foreign policy, of which Venice was forced to feel all the precariousness of its own inferior status. The (by-now wrinkled and torn) banner of the myth of good government was powerless before this clout and sway, and not unsurprisingly Amelot de la Houssay, a secretary with the French embassy in Venice, roundly demolished it in his Histoire du governement de Venise (Paris, 1676-77), a long-term bestseller of the period that managed to discredit the old Republican dame right into the next century. Y With his Della letteratura veneziana (Padua, 1752), Marco Foscarini, doge from 1762 to 1763, vainly spent himself in trying to reexhume Venice’s 16th-century civic wisdom in the waning strength of its 18th-century decline. More than recovering a glorious past, the conviction of the more thoughtful members of the Veneto government was that what was needed was sweeping reform and radical self-renewal. But this would mean ousting the patrician government itself and the tried and tested (as well as tired and sorely tested) Venice system. And not even the most enlightened of Venetian patricians (of whom there were quite a few) were willing to go this far. In the meanwhile, the Ducal Palace was very impressed with the enlightened “despotism” of Joseph ii (fig. 7) who, in Vienna and from Vienna, suddenly, peremptory decree after peremptory decree, through a slew of injunctions throughout the entire imperial realm, imposed on the realm itself a uni- history 0020.saggi.qxd 27 four centuries of relationships – conflict, rivality, hope 0020.saggi.qxd 28 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 28 form rationalisation whose aim was to suppress specificities and differences within the “various nations” now forced to become “a single, perfectly compact and solid body”. Except that (according to Daniele Dolfin, Venice’s ambassador to Vienna) this carefully planned “vast edifice”, its overall geometric architecture, its global disciplining of a perfectly aligned submission, its subjection and unified moves forward, “collapsed” as soon as it was built due to the “discontent” of the outlying areas of the empire and the quarrelsome and even rebellious reluctance of the “provinces”. And the Ducal Palace doubtless felt a sort of shiver of pleasure on seeing the rapid collapse and diagnosing the disintegration of the gargantuan reform. Venetian government, after all, had been accused by enlightened culture and reformed governments of a sluggishness that inhibited any attempt at reform. But was their inability to usher in reform with the pugnacity of Joseph II really criticisable? Or wasn’t it more a case of allowing the many centuries of wisdom to continue to inspire Venice’s ruling class who, loyal to themselves, conserved the appearance of a state consigned from the past, preserved the corporations, and respected local custom, local statutes, local variety and local difference? Might this conservatism not be a valuable lesson in cautionary wisdom pitted against the disasters of homologising “Josephism” or the furies of Jacobinist centralisation? Y But who was willing to listen to the level-headed teachings that might come from Venice when, in 1797, a final Napoleonic push brought to an end the life of the Serenissima, and all signs of an independent Venetian state were removed from the maps of Europe (figs. 8-9)? Venice had now become an ex-city, an exstate, an ex-capital. It was now simply an “under-city” – especially under Austria, especially under Vienna and, to a lesser extent, under Milan. It was no longer the Dominante, but a subject, perforce subjected, submissive (figs. 1 and 10) and, to some extent, posthumous city, whose past, centuries-old centrality can be gleaned from the endless reams of documents deposited in the Frari archives as a memento of the period of state command, of domination over land and sea under the aegis of Mark the Evangelist. Hence the 19th-century formation of analytical archives along endless kilometres of shelved documents pertaining to an earlier Venice. Thanks to this archival hording, it was now possible to study both past and present Venice. But despite this, according to common European perception the current Venice was 22-07-2009 10. Josef Carl Berthold Püttner, La fregata austroungarica “Novara” nel bacino di San Marco, Vienna, Heeresgeschichtliches Museum; il dipinto è successivo al 1862. Josef Carl Berthold Püttner, The AustroHungarian Frigate “Novara” in St Mark’s Basin, Vienna, Heeresgeschichtliches Museum; painting is post1862. 11:27 Pagina 29 not so much seen as a city that, through close scrutiny in the Frari archives of its past as city-state, was in some way reliving this glorious past, but rather a city that had suddenly lost the ability to recount itself: it had become aphasic, tongue-tied, virtually lifeless. And, in the silence typical of the deceased, it was others who spoke of Venice, who pulled and poked at the city with their mournful comments: Venice had become for them a necropolis, a decomposing body, a graveyard remnant. Venice had become the city of death (fig. 11), where people came to die, as did the Silesian poet Moritz von Strachwitz: in August-October 1847, devoured by consumption, the dying poet felt, despite the fact that he would eventually die in December 1847 in Vienna, fully consonant with the disintegration of the corroded, worm-eaten palazzi giving onto the canals. By the early 20th century, Venice had become the plague-ridden city where Mann’s enervated Aschenbach comes to die: he crumples onto the Lido beach as Tadzio’s profile disappears. Y Poets and writers under the thrall of a nolonger-existing Venice (the former Venice, obviously), now dressed in mourning, a widow in weeds, phantasmal, larval, to be used as a soft keyboard for Romantic funereal hammering, and to be sniffed out as the rotting, unhealthy greenhouse where extreme, decadent situations, orgasmic spasms and the throes of death can be set. Giacinto Gallina’s nobleman Vidal goes all out to live. D’Annunzio’s Stelio Effrena does his haranguing and establishes himself in a Venetian alcove. There are no such Romantic pangs, however, and no decadent complications in the documents produced or arriving in Vienna, and that were archived in Vienna by the Austrian administration. For the Habsburg government, Venice was not the same nocturnal, worn out city, or Piranesian debris floating in waters about to swallow it up (fig. 12). It was alive, even vivacious, in truth frightening as the Risorgimento idealism began to take root there. The revolutionary biennium 1848-49 was anti-Austrian, anti-Vien- history 0020.saggi.qxd 29 four centuries of relationships – conflict, rivality, hope 0020.saggi.qxd 30 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 30 nese. Vienna did manage, then, to put out the revolutionary fire, but found it difficult to regain control. However, in its three phases, with as many breaks in continuity, Austrian Venice was not suspended over an abyss, as the poets suggest, but was, instead, active, reactive and industrious. And its problems were those associated with the normal ebb and flow, waxing and waning, of life, not those of an imminent end: should the rii be filled in? Should more bridges be built? Should more walkways be built at the expense of ferry services across canals and rii? These problems were dealt with by local administrators, though supervised by Milan and Vienna. The important decisions were taken by the former and the latter. Commands arrived from both. 19th-century, Austrian Venice was marked and characterized by the end of its insularity. Railway or no railway? Obviously, if they opted for trains, then they would need a railway bridge. The very railway bridge Strachwitz arrived by. But he was completely concentrated on ending his days in the city where the palazzi crumbled into the waters of the canals that weave through the city, as black as the black of night; he was deaf to the chugging of locomotives, blind to the hordes who walked and worked in the city. Heaven forbid that this should be taken as a criticism. Even if the city was alive and on the verge of revolt, it was often depicted as dead; this was the note cultural production tended to insist upon most. Y And in 1866, Venice was annexed to the Kingdom of Italy. Vienna’s documents, reports, accounts, acts, protocols, statements and entries, however, remain silent on this point. This was no longer a matter for the ministers of the Kaiserhof. Conversely, it was authors who were either born in Vienna or who were nonetheless active in Vienna who looked to Venice, and even moved there. Trains, as Carducci had it, cross mountains and devour plains. And Venice is very close to hand for Vienna. Both cities are rendered in chiaroscuro by Rilke (born in Prague, but educated in Austria – military school at Sankt Pölten, commerce academy in Linz, through which his father had wanted to force him into a precise role within the Austro-Hungarian empire) when, from 1897, he intermittently began to lay the groundwork for his sensibility in Venice. It was in Venice, unlike Vienna, as he wrote to his wife in 1907, that “one finds unspeakable things”. Rilke was then writing The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, which character, still a child, vaguely intuits that life “would be”, for him, “full of strange [and therefore ‘unspeakable’] things”, things that would virtually be precluded to most 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 11. Didier Barra (Monsù Desiderio, prima metà xvii secolo), Veduta fantastica di Piazza San Marco, Londra, collezione privata. Didier Barra (Monsù Desiderio, first half of 17th century), View of St Mark’s Square, London, private collection. 11:27 Pagina 31 people and, at most, would be understood by one person alone. This one person is Malte, who encounters the unspeakable in Venice when (tearing himself away from the Venetian tourists who have been dazed by the swaying and rocking of the gondolas that introduce them to the vision of a “slack, opiate-like” Venice) he is pierced by a vision of the authentic, “real” Venice that has not been trivialised by tourist consumption. There are no sweet kisses and languid caresses and shapely forms enhanced by soft veils in the moonlight and/or hotel; there are no hot, nocturnal embraces between legitimate couples on their honeymoon, or more or less clandestine lovers, or more or less adulterous paramours. But, rather, a vigorous and energetic “morning” city, “created in the midst of nothing”, a “sleepless dockyards” that bursts into the story as “an example of austere, demanding will”. Just like Malte, Rilke was struck by this Venice. In a poem written between 1907-08, Rilke feels the city rise “from the depths”, from ancient skeletons of forests with an invincible leonine will impersonated by a fleet that, being pushed by a “morning breeze” sets off into the open sea. Y Captured, ensnared and seduced by Venice, Rilke (whose father wanted him to become an officer in the imperial army; had he listened to him, he might well have had a brilliant career, moving from garrison to garrison, awaiting a transfer to the 31 four centuries of relationships – conflict, rivality, hope 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 12. Richard Parkes Bonington, Il Canal Grande, 1826/1827, Washington, National Gallery of Art. Richard Parkes Bonington, The Grand Canal, 1826-1827, Washington, National Gallery of Art. 32 11:27 Pagina 32 Ministry of War in Vienna, whispering “Vienna! Vienna!”) refused to slip into “pure enchantment”, but wanted to grasp the city’s “secret” and understand its essence, as he wrote in a letter in 1912. And in the meanwhile, in Vienna Hugo von Hofmannsthal (who was Viennese through and through: his juvenile “room in Vienna” was his “entire world”) continued to fret over Venetian themes, just as he had done in a theatrical fragment on the death of Titian, with the tragedy Das gerettete Venedig and the short story “Der Brief des letzten Contarin”. In around 1912, Hofmannsthal began his difficult, protracted and unfinished draft for a novel, whose original title varied from “Diary of the Venetian Voyage of Mr N” and “The Venetian Adventure of Mr N”, ultimately settling on the more enigmatic but also perhaps more representative title (at least in reference to the contents, which deal with overcoming the lacerating tension between ethics and aesthetics, bringing together what has been cut asunder, and recomposing what has been cleft) of Andreas oder die Vereinigten [Andreas or The Reconjoined], under which title it was eventually published as a fragment, part of a narrative that was brusquely cut short and left unfinished. Y How, after all, can you re-compose when the practicable closures are virtually multiplied? In any case, the protagonist is Andreas, who moves from Vienna in 1778 (as the empress MarieThérèse (fig. 13) is ruling with her moderate, well-tempered reformism, while her son Joseph, the future emperor, is champing at the bit for even greater reforms) moves to Venice. The imperial capital is “too august”, too simple and too univocal for the young Andreas to provide answers to his nagging questions. He hopes the answers might come from and in Venice, that it is only here that he would be permitted to plumb the greatest depths of things to find his answers. In fact, the city he arrives in is bewildering, nocturnal, masked. His quest becomes an “adventure”: mystifying, concealing, misdirecting the jumble of appearances, but also illuminating, revealing the extent to which the profundity that can be found in the superficial aspect of things should not be excluded, the extent to which truth can be found coincident with the ambiguity of the mask, plumbing the deepest depths to find oneself, far from being resolved in a “descent into our interior” consists, on the other hand, in giving in to the oscillating and contradictory prowling of the most dispersive circumstances. Hence, there is no concentrating with the 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 33 presumption of consistency, but ductile, flexible readiness and willingness. No self-stethoscoping that moves within, but a wandering attempt at finding oneself without. To Venice, to Venice, in the without-est without. Except that Andreas does not recompose himself in Venice: he is splintered, he is lost. If, during his trip to Venice, he met a young, fullhearted girl in a mountain valley farm, with its genuine and simple life, then in Venice Andreas splits in two when he meets a young lady and an attractive courtesan. The former represents a rarefied spirituality; the latter a torrid, uninhibited sensuality. Or so it would appear at first glance. But only up to a certain point. There is a touch of repressed disquiet in the former’s demeanour. The latter’s carnality is disturbing. And the situation becomes morally murky when the courtesan tries to convince Andreas to seduce the young lady. She slyly urges him to abandon his obsession with “truth”; it is merely a “stupid word”. Y It is certain that, sooner or later, and now rather obviously later than sooner, Andreas should return to Vienna and do something concrete. But how to ready himself for the “return trip” when, to his dismay, he notes he cannot “at all go back to the limited existence of Vienna”? The young man is in a quandary, just as is the author about what to get him to do. As soon as he had arrived in Venice (at dawn, rudely deposited by a rough boatman along a remote, deserted fondamenta), Andreas had been lucky enough to have been helped in finding his bearings by a kind man wearing a mask who had providentially appeared from a calle. At first lost and incapable of orienting himself in the deserted city, he finds in galant Sagramozo, or Sacramozo (this is the masked man’s name; and yet his identity also consists in self-masking), an exceptional mentor, a sort of Virgil. He is an uncommon, extraordinary person. If he lives in Venice, “fusion of antiquity and the east”, it is because it is impossible there to fall into “the futile and the petty”, it is because, more than elsewhere, you can be worldly and, at the same time, pensive, give some meaning, an added layer, to existence. A teacher for Andreas, who is anxious to help this man who loathes univocality to mature, masters com- history 0020.saggi.qxd 33 four centuries of relationships – conflict, rivality, hope 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 13. Anton von Maron, Ritratto di Maria Teresa d’Austria, 1772, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Gemäldegalerie. Anton von Maron, Portrait of Marie Theresa, Empress of Austria, 1772, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Gemäldegalerie. 34 11:27 Pagina 34 plexity and seems able to re-compose the disjointed. Except that he accidentally kills himself. His is a philosophical suicide, but for Andreas it constitutes immense grief, an insurmountable loss. Lost, he feels like an orphan. Y Just after the first words had been written in the tormented and unfinished draft of Hofmannsthal’s novel the Viennese Schnitzler immersed himself in Casanova’s memoirs, between November 1914 and February 1915. An operative reading that led, in October 1917, to a verse play (with a 32-year-old Casanova full of joie di vivre, all seductive energy) and a long short story, or short novel, where Casanova is once again the leading character. Except that, now a poorly 53-year-old, he has lost his sheen, and seems even older than he is. He is rusty, feeble, morose, heavy set, with some lingering desire to dress well, except that he looks awkward in his once elegant suit, which is now worn out, torn and hastily patched up so that it will last a little longer. Penniless, he cannot buy new clothes. Now in Mantua, he insists on frequenting the high society that you would expect in a small provincial town. In an effort to conquer the fresh charms of Marcolina, he deploys all the artifices of his once efficacious, appreciated and much-requested conversational skills. But now they are mouldy, rancid and, what’s much worse, boring. And Marcolina is bored: vexed by his attempts to seduce her using these old stratagems, she cannot conceal her contempt, and uses her corrosive sarcasm to dismantle his tired charade and make him conscious of just how old-fashioned his polished eloquence is. Y The elderly adventurer is humiliated by being forced to admit that, once a lean, mean seducing machine perfectly balanced between physical prowess and verbal dexterity, he is now ready for the scrapheap: stiff-limbed, awkward in his movements, his face flabby, his conversation tired and farraginous. He has lost all his fascination. He can no longer seduce anyone. As for Marcolina, he disgusts her. She finds him loathsome. But he refuses to bow out graciously. His humiliation is not a passing incident: it signals the end of the foolish ambitions for a Casanova whose identity was constructed in terms of great seduction and irresistible conquest. But Casanova is nothing if not a marauding animal, a predator, and he will conquer Marcolina using the most abominable and contemptible of deceits. She has a lover, a young, dashing officer. And Casanova will come to an agreement with 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 35 him. In his malevolent senescence, he has learnt to bring out the worst in himself and others. The dirty old lecher and the young scoundrel seem made for each other, both of them sharing a taste for rapacity. Casanova, having won 2,000 ducats, hands the money over to the young man, who has lost it. In exchange, he agrees to help Casanova in fraudulently slinking into Marcolina’s otherwise inaccessible bed. He lends him his cloak, under which, at night, in the pitchest black, Casanova is greeted by Marcolina in her bedroom. Having managed to fob himself off as her lover, he manages to bring to bear all his old passionate vigour and is requited by Marcolina. As the sun rises, however, she realises, to her “indescribable horror”, that she has been tricked not only by Casanova, but also the young man she thought she loved. She realises that she has spent the night making love with Casanova, and not her young lover. Y Casanova cannot bear the “horror” she communicates. Imbued with this horror, aware of the revulsion she feels for him after he has soiled her, wearing the indelible sign of his repulsion, Casanova flees. He is blocked by her lover, and not because he has had a change of heart and is feeling guilty: it is simply that he hates Casanova too much, and he hates himself for having worked in cahoots with him. The two are cast in the same mould, almost interchangeable: Casanova a young version of himself in his rival; the young lover sees what he will become as he grows older. They thus hate each other. The duel is to the death. It is like a doubling in hatred of a single existence which is the sum of roguish youth and senescence turned nasty. By this reasoning, the homicidal fury that has pitted them against each other also has suicidal valency. In destroying the other, they are giving vent to a self-destructive desire. Casanova comes out on top: in one fell swoop, he strikes his sword into the heart of the young officer. As he lies dying, Casanova flees to Venice, where he will hide out unpunished. Here he resumes his old job: spending his time at the Quadri café, he is paid to pick up titbits of information for history 0020.saggi.qxd 35 four centuries of relationships – conflict, rivality, hope 0020.saggi.qxd 36 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 36 a state that, rotten to its core, dreads even the idle chit-chat of those who frequent cafés and bars. The Quadri closes in the dead of night. All whisperers have left, and Casanova has no one to listen in on. He, too, can leave. He crosses St Mark’s, deserted, oppressed by a low, sooty, starless sky. Walking through dark calli, up and down the little bridges under which flows a blackish, muddy water as if it were being pushed along to meet up with the “eternal Stygian waters”, Casanova reaches the miserable little hotel where, in a stark little room, he falls, exhausted by a “painful tiredness”, onto a “terrible” bed. Mercifully, around dawn, he is offered his “much desired sleep”, its “dreamlessness” swallowing him up and almost hopefully promising not to wake him up again so that he no longer has to look at himself in the mirror with the same “horror” that was in Marcolina’s gaze as she looked at him. Y A 1778 Venice in which Andreas deceives himself into thinking he can reforge his split ego, and in which an elderly Casanova crouches like an animal that has been dealt a mortal blow. Venice must bear the honour and responsibility of a more than millenarian history, so difficult to bear that it can hardly stand upright; the city lurches forward, almost reeling. Its life was to be short-lived. On May 12, 1797, the Maggior Consiglio resigned, and with it the entire regime. A provisional Municipality was sworn in, only to be swept aside on October 17, at Campo Formio. There Napoleon and Francis I worked together in destroying Venice’s statutory independence; they doled out the spoils of a state they had agreed to annul. This was the end. And it has a date. Fixed forever as the date of death. What has no precise date, however, is the positioning of a world as it comes to a close. And perhaps a world might well be close to its own demise and not know or be aware of it. Vienna in 1913, for example, was making preparations for a great feast to mark the 70th anniver- 22-07-2009 14. Polena della “Kaiserin Elisabeth”, incrociatore varato nel 1854 e autoaffondato il 2 novembre 1914 nella baia di Kiaochu, due giorni prima della resa ai giapponesi, La Spezia, Museo Tecnico navale. La polena raffigura l’imperatrice Sissi nel pieno del fulgore, proviene dal museo della Marina austro-ungarica di Pola, dove finì dopo il disarmo dell’unità che, nel 1866, aveva partecipato alla battaglia di Lissa. Figurehead of the “Kaiserin Elisabeth”, battle cruiser launched in 1854 and sunk in Jiaozhou Bay in 1914, two days before Japanese surrender, La Spezia, Museo Tecnico Navale. It depicts the empress Sissy at her most stunning, and comes from the Austro-Hungarian naval museum in Pula, where it ended up when the ship, which had participated in the 1866 Battle of Lissa, was decommissioned. 11:27 Pagina 37 sary of the long-lasting reign of Franz Joseph I in the none too distant 1918, and had no idea it was living its final years. An honours committee was formed, the general secretary of which, it should be remembered, was Musil’s man without qualities. The aim of the committee was to exalt Kakania and underline the sense of its historical presence. But, as we know, world war one destroyed Kakania. And Vienna, its capital, would find itself once more comparable to an enormous head for a very small body. Finis Austriae. It is obvious that the collapse occurred in 1918 (fig. 14); but when do we begin to perceive that a world is about to end? Hofmannstahl and Schnitzler lived just long enough to become familiar with the Vienna of the belle époque as well as the Vienna that was swept away by defeat. In the former Vienna they gleaned the subterranean indications of the landslide, detachment and final destruction. It was nonetheless in breathing the air of the end of the world that the two invented Venetian stories set in a Venice that (with hindsight they were well aware of this) had only a few years left to live. They wrote, in Vienna, in the vicinity of a collapse of the world they were born, grew up and matured in, of characters who, in their turn, move along the edges of an imminent finis Venetiarum. One would be tempted to say that finitudes sniff at each other, look for each other, recognise each other and almost stroke each other; they even take a liking to each other and establish elective affinities. Y On the other hand, if the bell tolled for the Serenissima, how to exclude that the funereal bell might not also be ringing (sooner or later, perhaps more later than sooner) for others, or for everyone? England in 1816, when Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage was published, was triumphal if not domineering. But the author warned (a warning that was ignored for over 100 years, if you consider Kipling’s triumphalism) against the haughtiness of the most powerful power: “In the fall of Venice, consider your own”. Memory is prophetic. At least, in Byron, who thus went beyond an emotional participation in the mourning of a preceding Wordsworthian sonnet, memory is offered the melancholy homage of condoling tears. history 0020.saggi.qxd 37 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 38 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 39 uno storico nemico, che priva la serenissima della libertà tra ambasciatori e spie artisti e musicisti: secoli di rapporti in cagnesco Fabio Isman 1. Sebastiano Ricci, Bacco e Arianna (particolare), Pommersfelden, Graf von Schönborn Kunstsammlungen. Sebastiano Ricci, Bacchus and Ariadne (detail), Pommersfelden, Graf von Schönborn Kunstsammlungen. Y Leonardo Donà, o Donato (1536-1612), figlio di Giovanni Battista e di Giovanna Corner, stirpe di commercianti non particolarmente doviziosa, sei fratelli e uno solo sposato, è il novantesimo doge della Repubblica di Venezia dal 1606: il secondo dei tre del casato, come tanti altri foriero di storie e di leggende (una riguarda un Ludovico, creato cardinale da Urbano iv Pantaleon nel 1378, ma poi, sospettato di tradimento e annegato con altri cinque porporati; ci sono anche un Andrea, «corrotto dal duca di Milano» e imprigionato nel 1447; un Giuseppe, pubblicamente impiccato nel 1601 perché ritenuto spia spagnola; un Antonio, bandito per peculato nel 1619; e un Paolo, esiliato ma poi graziato nel 1704, per un omicidio causato dalla «gelosia verso una monaca»). Leonardo, quello cui Galileo mostra per primo il suo telescopio nel 1609 sul campanile di San Marco, edifica il palazzo alle Fondamenta Nove, secondo alcuni disegnato, e chissà perché, da fra’ Paolo Sarpi, ancora abitato, caso più unico che raro, dai discendenti. Succede a Marino Grimani e deve misurarsi con un problema assai spinoso: l’Interdetto emanato da papa Paolo v Borghese. Anche su consiglio di Sarpi, 18 giorni dopo l’elezione nominato consultore in jure e teologo della Repubblica, il doge risponde con un Protesto: ordina al clero veneziano di non tener conto dell’atto papale ed espelle i Gesuiti che non si piegano. Y Al dogato, Donà giunge dopo il consueto cursus honorum: podestà a Brescia, savio, ambasciatore in Spagna (a soli 33 anni), a Vienna, Parigi e Roma, bailo a Costantinopoli, governatore e procuratore di San Marco (dal 1591: lo celebra con un banchetto da 587 ducati, un terzo dei suoi proventi annuali). Quando era a Roma, si racconta che Sisto v Peretti gli avesse offerto il vescovado di Brescia, con la porpora; e anche di uno scambio di battute, assolutamente premonitore, con Camillo Borghese, il futuro Paolo v: «Se fossi papa, vi scomunicherei»; e «Se fossi doge, riderei della scomunica». Se non è vera, è ben inventata. Comunque, al ritorno, già da fine Quat- il contesto 0020.saggi.qxd 39 uno storico nemico, che priva la serenissima della libertà 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 2. Paolo Caliari detto il Veronese, Allegoria della battaglia di Lepanto, forse 1573, commissionata da Pietro o Onfrè Giustinian, Venezia, Gallerie dell’Accademia, già nella chiesa di San Pietro Martire, a Murano. Paolo Caliari, known as Veronese, Allegory of the Battle of Lepanto, perhaps 1573, commissioned by Pietro or Onfrè Giustinian, Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia, formerly in the church of San Pietro Martire, Murano. 40 11:27 Pagina 40 trocento, i diplomatici veneziani redigevano una relazione per la Serenissima. Il futuro doge lascia anche un Diario, inedito per 430 anni e pubblicato da Umberto Chiaromanni, in cui racconta la Vienna del 1577, all’indomani della riforma protestante e del Concilio di Trento, sei anni dopo la battaglia di Lepanto (fig. 2): quando, con Giovanni Michiel, già spedito lì nel 1564 e 1571, va a congratularsi con Rodolfo ii, divenuto erede del Sacro Romano Impero. Y «Tutta la città, dentro le mura, è fabricata di muro assai nobilmente et comodamente»; «belle strade tutte saliggiate di mattoni»; Santo Stefano è paragonabile alle «belle chiese in altre città d’Italia, per li ornamenti dei suoi pilastri pieni di belle figure», e la «torre ovvero campanile» è di «non minore altezza di quello che è ora il nostro campanil di San Marco»; sono ricchi di fontane e «artificii» i giardini, splendido «l’edificio di piacere» voluto da Massimiliano i. Non sono numerose le descrizioni come questa: di solito, gli ambasciatori veneti si limitano ai problemi (e alle chiacchiere) della corte; o alle tematiche militari, e legate alla difesa. E tanto più quelli che devono interessarsi di Vienna: nata relativamente tardi come potenza, legata a Venezia da scambi più culturali che commerciali, a lungo quasi un nemico alle porte, finché, e suona come una nemesi, non sarà proprio lei a privare definitivamente la Serenissima dell’indipendenza: a trasformare in suddita l’ex Dominante. Nel 1564, Giovanni Michiel la racconta già tra le «principali d’Europa per la ricchezza e la fortificazione»: deve il suo ruolo al «continuo comertio con le provincie, alle quali è scalla principale»; ma la prima relazione di cui si sa, risale al 1496: la illustra Zaccaria Contarini il 12 luglio, spiega Marino Sanuto nel primo dei 52 volumi dei Diarii. Y All’inizio del secolo in cui Donà e Michiel ci descrivono la capitale austriaca, Venezia ha toccato i 150 mila abitanti; nello 22-07-2009 3. Tiziano Vecellio, Ritratto del cardinale Ippolito de’ Medici, Firenze, Galleria Palatina, Palazzo Pitti. Titian, Portrait of Ippolito de’ Medici, Florence, Galleria Palatina, Palazzo Pitti. 11:27 Pagina 41 stesso 1500, invece, Vienna ne totalizza ancora 20 mila. L’Austria come la conosciamo oggi, nasce abbastanza tardi. Prima, sono tanti feudi; nella Marca orientale (Östmark, poi Österreich, cioè impero d’oriente), nel 1278 s’insediano gli Asburgo con Rodolfo i, sostituendo gli estinti Badenberg; dal 1440, sono eredi del Sacro Romano Impero (tuttavia, nel 1485 Vienna è occupata dall’ungherese Mattia Corvino; e nel 1519 cede a Madrid il ruolo di capitale imperiale). Nel 1526, unificate le corone di Boemia, Ungheria e Croazia, nasce una delle maggiori potenze continentali, anche se trent’anni di guerra, chiusi nel 1648 dalla pace di Westfalia, cancellano ogni speranza di dominare sulla Germania e sulla stessa Europa. Y A lungo, gli scambi con l’Italia seguono altri itinerari. Fino a metà Seicento, il lodigiano Giovanni Pietro Telesphoro de Pomis (1569-1633) e Donato Mascagni di Firenze (1579-1637), dipingono a Graz e Salisburgo, come il comasco Santino Solari (1576-1646). Ma ancora più famoso in loco è il ticinese Carpoforo Tencalla (1623-1685), che si forma tra Milano, Bergamo e Verona: è pittore di corte di Ferdinando ii, chiamato dalla moglie di questo Eleonora Gonzaga; affresca sale nella Hofburg, il palazzo imperiale; si esprime nelle maggiori chiese della capitale e in vari castelli della regione (anche nel palazzo episcopale di Kromeriz, locali purtroppo bruciati come quelli di Olomouc; il fratello Giovanni Pietro ne è l’architetto, e il luogo conserva Il supplizio di Marsia, tra le ultime opere di Tiziano, comperato a Venezia da Thomas Howard, conte di Arundel, nel 1620). Tencalla lascia il proprio capolavoro, non finito, nel Duomo di Passau; e verosimilmente incrocia l’architetto Carlo Antonio Carlone, s’ignora se di Como o Milano (1634-1708), il contesto 0020.saggi.qxd 41 uno storico nemico, che priva la serenissima della libertà 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 4. Medaglia celebrativa della fondazione di Palmanova, 1593, Padova, Museo Bottacin. Commemorative medallion celebrating the founding of Palmanova, 1953, Padua, Museo Bottacin. 42 11:27 Pagina 42 che progetta e trasforma numerosi complessi ecclesiastici di Vienna e dintorni, come la celebre abbazia di Sankt Florian, poi “regno” del musicista Anton Bruckner (1824-1896). Da Milano e perfino da Napoli, nel tempo giungono Giuseppe Arcimboldi (1527-1598) e Martino Altomonte (1657-1745); da Como, Francesco Martinelli (1651-1708) e Donato Felice d’Allio (16771761); da Trento e Rovereto, Andrea Crivelli (1528-1558) e Gabriele De Gabrieli (1671-1747); da Mantova, invece, Ludovico Ottavio Burnacini (1636-1707); e altri ancora. Tra le rare eccezioni, Giovanni Giuliani da Venezia (1663-1744), scultore e stuccatore anche per i Liechtenstein, e lo scultore vicentino Lorenzo Mattielli (1680?-1748), che molto lascia proprio nella capitale, o lo stuccatore padovano del Seicento Ottavio Mosto, attivo a Salisburgo. Tra i precursori veneziani, di cui diremo, anche un breve viaggio di Pietro Liberi, e maggiori impegni di Antonio Bellucci e Sebastiano Ricci all’inizio del xviii secolo. Y Infatti, i rapporti con Venezia attengono particolarmente alla musica e più limitatamente alla pittura, e si manifestano soprattutto dal Settecento; prima, sono soltanto le relazioni degli ambasciatori e l’attività delle spie. Perché le due città si guardavano in cagnesco. Gli Asburgo possedevano la Carinzia e il Tirolo già dal Trecento; dal 1366, Duino, vicino a Trieste (dei Turn und Taxis, divenuti, in loco, Torre e Tasso), e dal 1382 la stessa città giuliana, la cui carriera è così antagonista alla Dominante. Nel 1508, l’imperatore Massimiliano i attacca in terraferma, con Luigi xii di Francia, fonda la Lega di Cambrai, cui aderiscono il re di Spagna e i duchi di Ferrara e Mantova: e la Serenissima perde, sia pur provvisoriamente, la Terraferma. Da metà Cinquecento, l’imperatore nutre ancor più cupe mire addirittura sulla navigazione in Adriatico, “porta” di Venezia sul mondo e chiave dei suoi commerci: la ostacolano gli Uscochi, profughi albanesi e serbi fuggiti dall’occupazione islamica, ma insediati in territorio asburgico. Vienna è baluardo contro l’invasione dei Turchi, che l’assediano nel 1529 e 1683, 200 mila uomini, 25 mila tende; nel 1532, li combatte anche Ippolito Medici, che Tiziano eterna in abito all’ungherese, per evocarne il comando su 4.000 moschettieri (fig. 3). «Bastione di tutto il resto d’Europa» e «chiave della Cristianità», chiamano gli ambasciatori la capitale austriaca; ma chissà se il Senato veneziano, il 17 settembre 1593, fa edificare la città-fortezza di Palmanova più in chiave antislamica, o – è assai verosimile – quale baluardo contro gli Asburgo, 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 43 il contesto 0020.saggi.qxd 5. Gioco del Biribissi, seconda The Game of Biribissi, second half of 18th century, metà del xviii secolo, Venezia, collezione privata. Venice, private collection. 43 uno storico nemico, che priva la serenissima della libertà 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 6. Jacopo Robusti detto il Tintoretto, Ritratto di Sebastiano Venier, 1576-1577, Treviso, collezione Alessandra. Tintoretto, Portrain of Sebastiano Venier with a Page, 1576-7, Treviso, Collezione Alessandra. 44 11:27 Pagina 44 comprensibilmente preoccupati dai lavori in corso. Del resto, già nel 1500 Leonardo era stato convocato per progettare una difesa sulla linea dell’Isonzo, come certifica il Codice Atlantico. Lo stesso Leonardo Donà (con Marino Grimani, Giacomo Foscarini, Marc’Antonio Barbaro, Zaccaria Contarini) fa parte di una qualificata commissione per localizzare la nuova città forte, e lascia un Diario dei sopralluoghi nel 1593 (fig. 4). Y Per cui, ambasciatori e spie: professione assai commendevole fin da quando L’arte della guerra del cinese Sun Tzu, un generale forse coevo di Confucio, vi secolo a.C., afferma che «andar con ordine pubblico a spiar ciò che si fa nei Paesi di cui si vive con sospetto, è cosa da persona molto onorata»; già praticata dal re Sargon, in Mesopotamia nel 2350 a.C., e non ignota a Mosè, che invia dodici spie nella terra di Canaan. Però, ai Romani i delatores non sono mai piaciuti; e, per citare un caso, nel 1587, a Venezia, Tomaso Garzoni li definisce «infami». La parola spia compare in laguna nel 1264, e almeno da allora, è proverbiale l’apparato della Serenissima, in patria e all’estero: già al 1226 risale la prima testimonianza di una scrittura cifrata, e numerose sono le successive apparizioni di codici segreti. Né l’Austria è da meno: celebre il “gabinetto nero”, voluto da Leopoldo i a metà del Seicento per intercettare la posta recapitata dai Turn und Taxis in tutt’Europa. Nel 1774, il bailo a Costantinopoli giustifica l’invio di un dispaccio via Cattaro spiegando che a Vienna «tutto si apre»; ma anche in laguna la pratica era consolidata. Dell’apparato veneziano, si sa, fa parte pure Giacomo Casanova, che trascorrerà nella capitale austriaca un tratto dell’esilio: in un delizioso libro sulle delazioni del Settecento, ad esempio, lo scrittore Giovanni Comisso include una sua maledicenza del 1782, più che un rapporto, contro Carlo Grimani «del fu N.H. Ser Michiel», che parla, «senza scrupolo alcuno, col Ministro di Russia»; ma forse, il primo incarico spionistico è proprio in chiave antiaustriaca: gli inquisitori lo spediscono a Trieste nel 1773, per convincere al ritorno alcuni monaci armeni emigrati da San Lazzaro, che avevano aperto una tipografia nella città. Y Dunque, ambasciatori e spie. Vienna vanta un arsenale, da cui, 1559, Ferdinando ii progetta di far salpare 400 «nasade» con 12 mila uomini a bordo, spiega Leonardo Mocenigo: poi, però, non realizza l’intento; ma nel 1563, sono pronti 12 «legni», «fuste» fabbricate da veneti «banditi» e «bregantini» da 13 a 20 «banchi», si intende di rematori, e 150 «nassate» da 28 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 45 scalmi ciascuna; anche nel 1738 l’ambasciatore Niccolò Erizzo ha un occhio di riguardo per quattro unità realizzate sul Danubio, per merito del capo della marina austriaca, il marchese Giovan Luca Pallavicini. Ma l’ovvia attenzione per l’armamento è del tutto ricambiata: infatti, mentre si costruisce Palma, i dispacci parlano ripetutamente di «esploratori» asburgici infiltrati nella manodopera, e un capitano travestito da eremita è segnalato da un confidente nel 1620. E Vienna, ben prima del Terzo uomo (indimenticabile film di Carol Reed con Orson Welles e Alida Valli, 1949), si dimostra luogo d’intrighi: sempre nel 1620, un agente vi ottiene i capitoli segreti della Lega contro il Turco; qui, nel 1628, cade un réseau spagnolo a Venezia (le Istruzioni di Madrid giungono agli inquisitori lagunari); ed è da qui che, 1698, l’ambasciatore Carlo Ruzzini svela come lo zar Pietro i, in incognito, compirà un viaggio-lampo nella città dei dogi (si veda «VeneziAltrove» 2008). Anche il segretario di Luigi Pio di Savoia è un informatore; del resto da Roma, a fine Seicento, forniscono segreti perfino il cardinale Pietro Ottoboni, protettore di Scarlatti, Corelli, Händel, e lo zio, il futuro papa Alessandro vii Chigi, come racconta Paolo Preto. A metà Settecento, l’ambasciatore imperiale a Venezia riceve 400 zecchini per la «benevolenza»; a inizio secolo, era a libro paga un abate, traduttore delle lettere del governo a Vienna. Se serve, spuntano addirittura i sicari: Venezia li sguinzaglia, nel 1640, per un capitano che ha tradito e lavora per gli Asburgo, e nel 1662 per un impiegato del Bancogiro in fuga a Vienna con ingente somma; quattro anni dopo, l’ambasciatore veneziano è incaricato di «levare dal mondo senza pregiudizi all’immagine pubblica» Gabriel Vecchia, reo di «procedure abominevoli»; nel 1754, va avvelenato il friulano Pietro de Vettor: ha trafugato i segreti dello smalto, e vive nella città che (Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Strauss, Schönberg, Berg, Webern) è capitale anche della musica. Y Infatti, le spie hanno pure compiti di tutela economica. Nel il contesto 0020.saggi.qxd 45 uno storico nemico, che priva la serenissima della libertà 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 11:27 7. Albrecht Dürer, Festa del Rosario, 1506, Praga, Národní Galerie; già a Venezia, chiesa di San Bartolomeo, è acquistata nel 1606 da Rodolfo ii per 900 ducati (per i personaggi ritratti, si veda la legenda, fig. 8). Albrecht Dürer, Festival of the Rosary, 1506, Prague, Národní Galerie; formerly in Venice, church of San Bartolomeo, it was bought by Rudolf ii for 900 ducats in 1606 (for people depicted, see key to photo 8). 46 Pagina 46 i j e c e a f b g h 22-07-2009 8. Legenda: a. il papa (forse Giulio ii della Rovere); b. l’imperatore Massimiliano i; c. il patriarca Antonio Surian; d. il cardinale Domenico Grimani; e. l’elemosiniere di San Bartolomeo, Burkhard von Speyer; f. il duca Erich di Brunswick; g. uno dei Fugger, forse Jörg; h. Hieronymus “Thodesco”, di Augsburg, architetto che ricostruisce il Fondaco dei Tedeschi dopo l’incendio del 1505; i. Albrecht Dürer; j. Leonhard Wild, fondatore della Confraternita del Santo Rosario a Venezia. Key: a. Pope (perhaps Julius ii); b. Emperor Maximillian i; c. Patriarch Antonio Surian; d. Cardinal Domenico Grimani; e. The San Bartolomeo almoner, Burkhard von Speyer; f. Duke Erich of Brunswick; g. One of the Fuggers, perhaps Jörg; h. Hieronymus “Thodesco”, from Augsburg, an architect who rebuilt the Fondaco dei Tedeschi after the 1505 fire; i. Albrecht Dürer; l. Leonhard Wild, founder of the Confraternita del Santo Rosario (Confraternity of the Sacred Rosary) in Venice. 11:27 Pagina 47 1766, i segreti per fabbricare la porcellana giungono dall’ambasciatore di Parigi prima che un certo barone Suter possa trasmetterli all’Austria. Nel 1733, un cavaliere bergamasco informa da Vienna su cartiere e sali. Nel 1751, una spia va in missione per mezz’Europa (anche a Graz, Linz e Vienna), per informarsi di tariffe, fabbriche e traffici. Nel 1761, al diplomatico nella capitale austriaca si chiede di assoldare due operai di una fabbrica di paste da mortaio. Nel 1774, si tenta di far abortire il progetto di una strada, via Engadina, da Milano a Vienna; nel 1620, si progetta di catturare un ex corsaro inglese: detiene il privilegio per «fabricar saponi alla venexiana», ma non rispetta le regole. Nel 1724, il conte Rinaldo Zoppin è “convinto” a non esportare a Vienna «il Lotto di Genova e il gioco del biribìs» (fig. 5, uno dei tanti praticati in città, con nomi spesso coloriti: Faraone, amato pure da Casanova, Zecchinetta, Cressiman, Bazzica, Meneghella, Camuffo, Slipe e slape, Picchetto, Tresette, Gilè alla greca, Ombre, Tric trac, Bassetta; la parola “loto” è citata da Marin Sanuto per un’estrazione del 1522; quello “di Genova” compare sotto la Lanterna nel 1576, ma in laguna nel 1734; nel 1752, grazie a italiani, è importato in Austria. Nel 1761, bloccato il progetto di Vettor Erizzo di aprire un banco a Vienna; è protetta, e non va esportata, perfino l’arte del merletto: nel 1748, un tessitore udinese fonda uno stabilimento a Vienna, con operai sottratti a Venezia; sborsando 3.100 ducati, lo si fa tornare, senza che istruisca i dipendenti tedeschi. Nel 1777, l’ambasciatore in Austria aiuta a togliere di mezzo, acquistando sei copie da dei privati, una Narrazione definita «imprudente e detestabile». Y Quando non devono occuparsi di sicari, i diplomatici raccontano la città. Ne esaminano le fortificazioni, la macchina statale («un corpo senza organizzazione»: Michiel, 1678), le armi. Nel 1769, Paolo Renier, futuro doge, riferisce di «canòn di campagna» da 15 colpi al minuto, e di uno che si carica «a mitraglia», 400 passi di gittata. Ma nel 1793, Daniele Dolfin rende merito a Giuseppe ii per la concessione della libertà di culto e per l’abolizione della schiavitù (i “servi della gleba”), anche se permane vivo il «malcontentamento nelle provincie» formate da etnie eterogenee, e gli sforzi per rendere omogeneo il Paese sembrano vani. Se, dice il proverbio, l’ambasciatore non porta pena, spesso deve portare regali; al nostro Donà, l’arciduca Ferdinando chiede, per la sua collezione di armature storiche, quelle indossate a Lepanto dal doge Sebastiano Venier (fig. 6, anco- il contesto 0020.saggi.qxd 47 uno storico nemico, che priva la serenissima della libertà 0020.saggi.qxd 48 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 48 ra esposto nell’Armeria della Hofburg) e dal provveditore generale Agostino Barbarigo, che vi è stato ucciso, e una di Marcantonio Bragadin, scorticato a Famagosta, «et volse che di cio fusse per noi scritto, come facemmo alla Serenissima Vostra». Del resto, le comunicazioni tra le due città erano già da tempo intense. I collegamenti postali risalgono al 1558, quando il re polacco Sigismondo ii collega i suoi domini con alcune capitali del sud, tra cui Vienna e Venezia: tra le due città, il quotidiano servizio postale è tra i primi ad essere istituiti. Y Ma a percorrere quegli itinerari, nei due sensi, non erano certamente solo ambasciatori e spie. Nessuno quanto i tedeschi, genericamente intesi, ha forse mai amato e desiderato di più l’Italia; e, particolarmente Venezia, scoperta ben prima di Goethe. Dal medioevo, in città, i tedeschi avevano il loro fondaco accanto a Rialto (affrescato da Tiziano e da Giorgione); ne erano magna pars i banchieri Fugger, cui si deve il viaggio di Albrecht Dürer per realizzare per la chiesa di San Bartolomeo (1506) la Pala del Rosario, larga due metri e densa di autentici ritratti: papa e imperatore, lo stesso pittore, l’architetto del fondaco, il committente (figg. 7 e 8): nel 1606, Rodolfo ii la vorrà a Praga. Ma si trattava ancora di “todeschi”, e non austriaci. Erano di Augusta i Fugger, mercanti e banchieri dal Quattro e affermati nel Cinquecento (prestano 150 mila fiorini a Massimiliano i; con 500 mila contribuiscono alla elezione di Carlo v, 1519; aprono sede a Roma); come tedeschi sono i primi artisti “oltremontani” e “ponentini” a Venezia. Compreso Giovanni d’Alemagna, che nel 1446, con il cognato Antonio Vivarini realizza, nella Sala dell’Albergo di Santa Maria della Carità, il primo dipinto su tela documentato in laguna (fig. 9): un polittico (su lino) alto tre metri e mezzo, e lungo quasi cinque; impresa, oltre che da precursori, da veri titani, in cui la lavorazione dei broccati denuncia una tecnica complessa, di sicura importazione. Poi, i viaggi e i contributi nei due sensi s’infittiscono; e finalmente, riguardano anche l’Austria e Vienna che, del resto, cominciava appena a diventare una capitale. Vi lavora Pietro Liberi (1605-1687), e Leopoldo i lo nomina conte; a metà Seicento, Marco Boschini dedica la Carta del navegar pitoresco all’arciduca Leopoldo Guglielmo; poi, vi operano Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini (1675-1741, fig. 10), e Sebastiano Ricci (1659-1734, figg. 1 e 11): è a Schönbrunn, accanto a Johann Michael Rottmayr (1654-1730) che aveva studiato per undici anni a Venezia (come, un secolo prima, 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 49 il contesto 0020.saggi.qxd 9. Antonio Vivarini e Giovanni d’Alemagna, La Madonna col Bambino in trono e angeli tra i dottori della Chiesa, 1446, Venezia, Gallerie dell’Accademia. Antonio Vivarini and Giovanni d’Alemagna, Four Fathers of the Church triptych, 1446, Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia. Hans Johann Rottenhammer, di Monaco), da Johann Carl Loth. Loth nasce a Monaco nel 1652 e nel 1698 muore in laguna, la sua seconda patria; riceveva commissioni da tutte le corti europee, e dall’Italia importa la moda del bozzetto. Y Dopo di allora, è tutto un vai e vieni. Palazzo Liechtenstein conserva dipinti di Antonio Bellucci (1654-1726), di cui a Venezia resta solo un San Lorenzo Giustiniani (il primo patriarca) in San Pietro di Castello, fino al 1807 la cattedrale cittadina, e un cui studio per il Massacro degli Innocenti è andato da poco all’asta da Sotheby’s, stimato 9 mila euro (fig. 12), ma invenduto; e il nipote di Simon Vouet, Louis Dorigny (1654-1742), un parigino che adotta Venezia e il Veneto, decora la Rotonda di Vicenza, villa Manin a Passariano e il Duomo di Udine, e a Vienna affresca il palazzo di Eugenio di Savoia, allora il più rinomato dei condottieri. Daniele Antonio Bertoli (1677-1743) è disegnatore di camera di Giuseppe i, di Carlo vi e degli inizi di Maria Teresa, di cui era stato insegnante. La famiglia imperiale e gli aristocratici viennesi chiederanno poi ritratti a Rosalba Carriera (16751757), cognata di Pellegrini, che v’inizierà anche una serie delle sue Quattro stagioni eseguite pure per il console inglese Joseph 49 uno storico nemico, che priva la serenissima della libertà 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 10. Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini, Annunciazione, modello per la cupola della Salesianerinnerkirche di Vienna, Stoccarda, Staatsgalerie. Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini, Annunciation, model for the cupola of the Salesianerinnerkirche in Vienna, Stuttgart, Staatsgalerie. 50 11:27 Pagina 50 Smith, mentre Bernardo Bellotto (1721-1780) lascerà tante vedute della capitale (figg. 13 e 14) che Maria Teresa gli ha commissionato. Franca Zava Boccazzi racconta la vita singolare di Federico Bencovich (1677?-1756), un dalmata che un parente musico fa venire a Venezia e mette a scuola a Bologna da Carlo Cignani, attivo a Schönbrunn e Würzburg, cui guarderà il giovane Giambattista Tiepolo dipingendo il ciclo nella Residenz (fig. 15): quasi nulla di suo resta, la Seconda guerra mondiale distrugge il poco che sopravviveva. E chiudiamo la carrellata con Giovan Battista Pittoni (1687-1767), attivo a Schönbrunn e altrove, e i tredici Canaletto che i Liechtenstein vogliono per la loro collezione, pochi anni or sono ritornata a Vienna da Vaduz (fig. 16), dov’era stata trasportata alla vigilia dell’ultimo conflitto mondiale. Y Perfino più intensi sono tuttavia il côté musicale e quello letterario, di cui altri racconterà. Nel Cinquecento le note di Vienna non erano brillanti, né particolarmente memorabili; forse anche per le nozze di Ferdinando ii con Eleonora Gonzaga, i primi maestri di cappella vengono da Venezia: Giovanni Priuli (1575-1629) e Giovanni Valentini (1583-1649) studiano con Giovanni Gabrieli, e muoiono a Vienna; Ferdinando iii è incoronato al suono del Ballo delle Ingrate di Claudio Monteverdi; muore all’ombra del campanile di Santo Stefano anche Antonio Bertali, di Verona (1605-1669), che insegna musica all’erede al trono; fino agli ultimi giorni, a dirigere la cappella gli succede Giovanni Felice Sances, non molto noto (1600-1679), ma pure lui passato per le lagune. A Vienna, grandi mediatori culturali del tempo sono i riformatori del melodramma Apostolo Zeno (nato e morto a Venezia, 1668-1750), autore di 66 libretti e poeta cesareo per dieci anni dal 1718, e Pietro Metastasio (in realtà Trapassi: nasce a Roma, 1698, muore a Vienna, 1782), che gli succede con un salario di tremila fiorini l’anno, ma approda in Austria, dove vive al quarto piano del numero 12 di Kohlmarkt, «soltanto dopo la verifica veneziana dei suoi testi» (Giovanni Morelli). A 12 anni traduceva l’Iliade in ottave, è autore di 27 drammi per musica, 35 azioni teatrali, 8 oratori, serenate, poemi lirici, canzonette. A Venezia ha molte commissioni: dai Tron, dai Soranzo, dai Gradenigo, dai Tiepolo e mette in scena numerose prime. Quando lascia l’Italia ha già all’attivo i successi in laguna di Artaserse, Siroe e Didone abbandonata. Artaserse è musicato da Leonardo Vinci e Johann Adolf Hasse (che morrà a Venezia nel 1783): va in scena nel 1730, a Roma e al teatro di San 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 51 Giovanni Crisostomo; lo riprenderanno altri 85 autori, tra cui Gluck, Scarlatti, Johann Christian Bach, Galuppi, Paisiello e Cimarosa, per indicarne la popolarità. Siroe è ancora di Vinci, rappresentato a Venezia nel 1726, e ripreso da altri venti musicisti tra cui Vivaldi, Handel, Scarlatti, Galuppi, Piccinni; mentre Didone è di Domenico Natale Sarro, che la presenta nella sua Napoli nel 1724, ma ha successo dopo la ripresa veneziana di Tomaso Albinoni, 1725, tanto che lo stesso primo autore provvede a un rifacimento per la laguna nel 1730; fino al 1823 e a Saverio Mercadante, è adottata da 57 musicisti. In Austria, Metastasio esordisce il 4 novembre 1731, onomastico dell’imperatore Carlo vi, con Demetrio di Antonio Caldara (Venezia, 1670Vienna, 1736); e, secondo il perfido Lorenzo Da Ponte, vi muore di crepacuore, dopo la notizia che la pensione gli era stata sospesa. Tra le opere dell’ultimo maestro di cappella degli Asburgo venuto dalle lagune, Antonio Salieri (Verona, 1750-Vienna, 1825), curiosamente vi sono Semiramide di Metastasio, e Il pastor fido, su libretto di da Ponte, che conduce a Mozart, e lo racconta Sandro Cappelletto. Salieri giunge a Vienna al seguito del boemo Florian Leopold Gassmann (1729-1774), che dopo la scuola dal famoso padre Martini a Bologna, è al servizio dei conti Veneri a Venezia, da dove è chiamato a succedere a Gluck al Burgtheater; dopo la morte per un incidente del suo mentore, sarà Salieri a insegnare musica alle figlie, e a diventare Hofkapellmeister (fig. 17). il contesto 0020.saggi.qxd 51 uno storico nemico, che priva la serenissima della libertà 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 11. Sebastiano Ricci, Bacco e Arianna, Pommersfelden, Graf von Schönborn Kunstsammlungen. Sebastiano Ricci, Bacchus and Ariadne, Pommersfelden, Graf von Schönborn Kunstsammlungen. 52 11:27 Pagina 52 Y Fino ad allora, parecchi veneziani impugnano la bacchetta alla corte di Vienna, le cui vie «sono lastricate di cultura, e nelle altre città d’asfalto» (Karl Kraus). Già dal 1640, vi si rappresenta Francesco Cavalli (in realtà, Pier Francesco Caletti-Bruni, 1602-1676), cremasco ma a 15 anni cantore in San Marco da dove non si muove più: un unico viaggio a Parigi, invitato dal cardinal Mazzarino per un’opera che, nel 1660, rallegri le nozze di Luigi xiv, il re Sole, con Margherita d’Austria, figlia di Filippo iv re di Spagna; però il teatro non è pronto, e la pièce va in scena due anni dopo. Poi, tocca a Marc’Antonio Ziani (1653-1715) e Carlo Agostino Badia (1671-1738), defunti a Vienna come Antonio Draghi (1634-1700), nato a Rimini ma educato a Venezia, e, dal 1714, Antonio Caldara (3.500 composizioni all’attivo; allora, il vertice della musica austriaca con Antonio Lotti, pure veneziano, 1666-1740, esordio come cantore aggiunto a San Marco; forse, con Caldara termina la supremazia veneta nel teatro musicale barocco). Ci va anche Antonio Pancotto, dimenticato perfino dal Deumm, la “Bibbia” dei musicofili. Y Baldassarre Galuppi è ospite quando si esegue il suo Demetrio, su testo di Metastasio; e, parlando d’altro, vive lì una grande stagione (un’altra è a San Pietroburgo) Giovanni Battista Lampi, trentino formatosi a Verona, ritrattista ufficiale e disputato delle maggiori corti dell’epoca (fig. 18). Per Vienna passerà perfino, chiamato da Domenico Barbaja, impresario del San Carlo a Napoli, e dell’An der Wien e del Kätnerthortheater, Gioachino Rossini, di cui dieci “prime”, tra il 1810 e 23, sono riservate alla laguna, dal San Moisè alla Fenice. Una curiosità: nel 1742, dalla capitale austriaca arriva a Venezia Carlo Ginori, creatore della storica manifattura di Doccia, porcellane e maioliche, per chiedere consigli a Giovanni Vezzi, sfortunato pioniere in materia; ma è costretto a una scomoda quarantena al Lazzaretto nuovo. Debutta a 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 53 Venezia, ai Santi Apostoli nel 1649, l’aretino Antonio Cesti (1623-1669), che farà fortuna a Innsbruck; è tra i massimi autori del tempo, esaltato da Salvator Rosa, 1652 («In Venetia è divenuto immortale e stimato, il primo che oggi componga in musica»). E a Vienna, per finire, passa gli ultimi giorni, abbastanza misteriosamente e in modo sicuramente disagiato, anche Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741, fig. 19): vi era già andato, nel 1730 con il padre, a rappresentarvi Farnace; aveva già composto musiche per le nozze di Luigi xv e per l’imperatore Carlo vi, che aveva pure omaggiato a Trieste, ricevendone il cavalierato; forse, lo voleva incontrare di nuovo. Non più stimato come prima a Venezia, e osteggiato a Ferrara (il cardinale Fabrizio Ruffo vieta una sua stagione, anche «per l’amicizia con la Girò cantatrice»), nel 1740 se ne va. Ma non butta bene: Carlo vi muore; segue la guerra; lui svende i manoscritti. Vive presso una vedova, vicino al teatro dove sperava di rappresentare qualcosa: casa distrutta nell’Ottocento, al suo posto c’è l’hotel Sacher; e vi muore la notte tra il 27 e 28 luglio 1741: vicino alla Karlskirche (la cui volta è affrescata da Rottmayr, quello che studia a Venezia da Loth), una lapide ci ricorda che è sepolto lì, in una fossa comune. E la sua musica, oltre 550 concerti (una volta, dice De Brosses, si vantò d’averne composto uno più in fretta che il copista a trascriverlo)? Dimenticata fino al xx secolo. In centro, a piazza Roosevelt, per i 260 anni da quel giorno, è stato scoperto un monumento del veneziano Gianni Aricò: tre figure in marmo di Carrara rappresentano le sue “Putte” dell’Ospedaletto. Y Su tutto il resto (e ce ne sarebbe), passiamo a volo d’uccello. Grazie a Bernardo Bellotto sappiamo come la città degli Asburgo era ai suoi giorni. Il nipote di Canaletto esordisce con una veduta commissionata nel 1759 dal principe Wenzel Anton von Kaunitz-Riethberg, noto anche per aver voluto, in quei tempi difficili, una cappella con un pulpito per i cattolici e uno per i protestanti; poi, documenta tre castelli (il terzo è Schönbrunn) di cui due (Belvedere e Schlosshof) già di Eugenio di Savoia, oltre alle piazze e ai mercati; e Maria Teresa vuole per sé molte sue tele. Y Dalle collezioni di Carlo i, decapitato a Londra, giunge a Vienna parecchio di veneziano: spesso, capolavori assoluti. Nel 1798, mentre nella capitale d’Asburgo sollecita i pagamenti del vitalizio, Canova è officiato di un monumento funebre per Maria Cristina d’Austria, che dal 1805 è nella Augustinerkirche. E presto, in Laguna, fa fortuna un ritrattista che viene da Vienna e il contesto 0020.saggi.qxd 53 uno storico nemico, che priva la serenissima della libertà 0020.saggi.qxd 54 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 54 morrà in una calle: Ludwig Passini (1832-1903) vive a Roma, e lascia una celebre Veduta del Caffè Greco, ma gli ultimi 30 anni li spende a Venezia. Abitava a Palazzo Vendramin dei Carmini, e nel 1895, con Alma Tadema, Puvis de Chavanne, Gustave Moreau, Edward Coley Burne-Jones (per dire i nomi) fa parte del Comitato per la i Biennale (fig. 20); nella ii, esporrà un suo ritratto. Il giovane Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) – che a vent’anni quasi esordisce decorando a Fiume il teatro comunale con il fratello Ernst di due anni più giovane e il compagno di studi Franz Matsch – affresca intanto lo scalone del Kunsthistorisches Museum, e, tra l’Arte greca ed Egizia, dipinge il Rinascimento italiano (1890) in cui inventa anche il Quattrocento veneziano: ancora lontana è la Sezession, e ancor più il tributo della Biennale, che nel 1910 gli dedica una mostra, e Venezia ne acquista la Giuditta (fig. 21) Y Novecentesche anche le due ultime notazioni. Lega le due città perfino Gabriele D’Annunzio (fig. 22). Il volo su Vienna il 9 agosto 1918 (11 Ansaldo Sva della 87. squadriglia), avviene nel nome di San Marco (come si chiamava la Squadra aerea comandata dal Vate) e della Serenissima, che era il titolo dell’87. squadriglia; e il decollo, anche con l’asso dell’aviazione Arturo Ferrarin, avviene dal campo di San Pelagio, alle porte di Padova; degli undici partiti, sette giungono sulla capitale austriaca e liberano 50 mila copie di un manifestino scritto dallo stesso D’Annunzio. Infine, durante la belle époque, ponte tra le due città era anche il mitico Simplon Orient Express: da poco riesumato, con 12 carrozze-letto blu costruite tra il 1926 e il 1931; ma solo per pochi: negli scompartimenti-suite, il viaggio costa 1.600 euro a persona. 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 55 an historic enemy deprives the serenissima of its freedom ambassadors and spies, artist and musicians: centuries of perilous relations context 0020.saggi.qxd Fabio Isman 12. Antonio Bellucci, Studio per Il massacro degli Innocenti, andato all’asta da Sotheby’s a Londra il 22 aprile 2009, con stima di 9 mila euro. Antonio Bellucci, Study for the Massacre of the Innocents, auctioned at Sotheby’s, London, on April 22, 2009. Y Leonardo Donà, or Donato (1536-1612), the son of Giovanni Battista and Giovanna Corner, from a long line of not excessively wealthy merchants, with six brothers (of whom only one married), was the ninetieth Doge of the Republic of Venice. Elected in 1606, he was the second of three doges from the same stock, and like many others a portender of stories and legend (one such surrounded the figure of Ludovico, made cardinal by Urban iv in 1378, but then, suspected of treason, was drowned along with five other cardinals; another was Andrea, “corrupted by the Duke of Milan” and imprisoned in 1447; and Giuseppe, publicly hanged in 1601 because he was thought to be a spy for the Spaniards; yet another was Antonio, banished for embezzlement in 1619, and, finally, Paolo, exiled and then pardoned in 1704 for murder, caused by “jealousy towards a nun”). Leonardo (who was the first person Galileo showed his telescope to on the San Marco campanile in 1609) had a palazzo built at the Fondamenta Nove which, some maintain (and who knows why), was designed by Paolo Sarpi, and which is, strangely enough, still occupied by his descendents. He followed Marino Grimani, and had to deal with a very thorny problem indeed: the “Interdiction” emanated by Pope Paul v. Following Sarpi’s advice, 18 days after his election and nominated in jure consultant and theologian of the Republic, the doge replied with his own “Protest”: he ordered the Venetian clergy to ignore the interdiction, and had all Jesuits who refused to comply expelled. Y Donà rose to the position of doge following the usual cursus honorum: podestà at Brescia, savio, ambassador to Spain (at only 33), Vienna, Paris and Rome, bailo at Constantinople, governor and procurator of St Mark (from 1591, which he celebrates with a banquet that cost 587 ducats, or a third of his annual income). When he was in Rome, it was said that Sixtus v offered him the episcopal see of Brescia, and that there had been a premonitory exchange with Camillo Borghese, the future Pope Paul v: “If I were pope, I 55 an historic enemy deprives the serenissima of its freedom 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 13. Bernardo Bellotto, La Freyung di Vienna verso la facciata della Schottenkirche, 1750-1760, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Gemäldegalerie. Bernardo Bellotto, Vienna Freyung towards the Façade of the Schottenkirche, 1750-60, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Gemäldegalerie. 56 11:27 Pagina 56 would excommunicate the Venetians”; and “If I were doge, I’d laugh off the excommunication”. If it isn’t true, it’s certainly ingenious. However, as early as the late 15th century, Venetian diplomats were putting together a report for the Serenissima. The future doge also left a Diario, unpublished for 430 years until Umberto Chiaromanni finally published it, where he tells of the Vienna of 1577, just after the Protestant reform and the Council of Trent, six years after the Battle of Lepanto (fig. 2): when, with Giovanni Michiel, who had already been sent there in 1564 and 1571, he went to congratulate Rudolf ii, the heir to the Holy Roman Empire. Y “The entire city, within its walls, is rather nobly and richly made of stone”; “beautiful roads all paved with bricks”; St Stephen’s is comparable to all the “beautiful churches in other Italian cities because of the ornaments of its pillars full of wonderful figures”, and the “tower, or rather campanile”, is “as tall as what is currently our campanile at St Mark’s”; the gardens are replete with fountains and “playful devices”, and the “pleasure dome” wanted by Maximilian i is splendid. There are not too many descriptions such as this one; Veneto ambassadors usually limited themselves to the problems (and rumours) of court or military themes linked to defence. Even more so those who had to deal with Vienna. Vienna had come to the fore relatively late as a power, and was linked with Venice more for cultural rather than commercial reasons, and was for a long time seen almost as an enemy at the gate until (and this makes it sound like a nemesis) it was Vienna itself that definitively deprived the Serenissima of its independence when the former Dominante was subjected to Viennese rule. As early as 1564, Giovanni Michiel describes it as one of the “greatest in Europe in terms of wealth and fortifications”; its importance is due to its “continuous trade with the provinces, for which it is the main hub”. However, the first description we know about dates from 1496, where it is illustrated by Zaccaria Contarini on July 12, according to Marino Sanuto, in the first of the 52 volumes of his Diarii. Y In 1500, Venice had 150,000 inhabitants; in that same year, Vienna had 20,000. The Austria we now know came about much later. It was originally made up of a series of fiefdoms. The eastern March (Ostmarch, later Osterreich, i.e. “eastern empire”) was taken over by the Habsburgs with Rudolf i, replacing the extinct Badenbergs; they became heirs to the Holy Roman Empire in 1440 (nonetheless, in 1485 Vienna was occupied by the Hungarian Matthias Corvinus, and in 1519 Madrid became the empire’s official capital). In 1526, after the unification of the crowns of 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 57 Bohemia, Hungary and Croatia, one of the greatest continental powers was born, even though 30 years of war, which came to a close in 1648 with the Peace of Westphalia, ruled out any hope of dominating Germany or Europe. Y For a long while, relations with Italy followed other itineraries. Until the mid 17th century, Giovanni Pietro Telesphoro de Pomis (Lodi, 1569-1633) and Donato Mascagni (Florence, 1579-1637), were painting in Graz and Salzburg, as was Santino Solari (Como, 1576-1646). But even more locally famous was Carpofora Tencalla (Ticino, 1623-1685), who learned his art in Milan, Bergamo and Verona. Called by Ferdinand ii’s wife, Eleonora Gonzaga, he became court painter and frescoed the halls at Hofburg, the imperial residence, and contributed to the greater churches of the capital and several castles in the region (including the episcopal seat of Kromeriz, unfortunately destroyed by fire like that of Olomouc; his brother Giovanni Pietro was the architect, and the building houses The Flaying of Marsyas, one of Titian’s last works, bought by Thomas Howard, count of Arundel, in Venice in 1620). Tencalla left his unfinished masterpiece in the Passau cathedral, where he very likely met the architect Carlo Antonio Carlone (Como or Milan, 1634-1708), who designed and transformed various religious complexes in Vienna and surroundings, such as the famous Sankt Florian abbey, which later became Anton Bruckner’s (1824-96) “reign”. Over time, Giuseppe Arcimboldi (1527-98) and Martino Altomonte (1657-1745) arrived from Milan and even Naples; Francesco Martinelli (1651-1708) and Donato Felice d’Allio (1677-1761) arrived from Como; Andrea Crivelli (1528-58) and Gabriele De Gabrieli (1671-1747) arrived from Trent and Rovereto; and Ludovico Ottavio Burnacini (1636-1707) arrived from Mantua. There were many others. Among the rare exceptions there were Giovanni context 0020.saggi.qxd 57 an historic enemy deprives the serenissima of its freedom 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 14. Bernardo Bellotto, Vienna dal Belvedere superiore, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Gemäldegalerie. Bernardo Bellotto, Vienna from the Upper Belvedere, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Gemäldegalerie. 58 11:27 Pagina 58 Giuliani (Venice, 1663-1744), who undertook sculptures and stuccos for the Liechtensteins’ house, the sculptor Lorenzo Mattielli (Vicenza, 1680?-1748), who worked a great deal in the capital, and the 17th-century Paduan sculptor Ottavio Mosto, who worked in Salzburg. Among the Venetian precursors (about whom I will talk in greater depth later on), there was a brief trip undertaken by Pietro Liberi, as well as slightly more important work undertaken by Antonio Bellucci and Sebastiano Ricci in the early 18th century. Y In fact, relations with Venice are more in the musical sphere than in painting, and can be seen mainly in the 18th century. Before this, relations were mainly those officiated by ambassadors or undertaken by spies. And that is because the two cities usually looked daggers at each other. The Habsburgs had possessed Carinthia and the Tyrol from as early as the 14th century, Duino, near Trieste (now belonging to the Turn und Taxis, who have become, locally, “Torre e Tasso”), since 1366, and Trieste, whose own career was often that of antagonist to Venice, since 1382. In 1508, the emperor Maximilian i attacked the mainland, and Venice counter-charged by conquering Pordenone, Gorizia, Trieste and Fiume. That same year, along with Louis xii of France, Venice founded the League of Cambrai, joined by the king of Spain and the dukes of Ferrara and Mantua; yet the Serenissima loses, albeit only temporarily, control over the mainland. From the mid 16th century, the emperor had even darker aims to control navigation in the Adriatic, the “doorway” from Venice to the world and the cornerstone of its commercial success: the Uskoci, Albanian and Serbian refugees fleeing from Islamic occupation but within Habsburg territory, constituted an impediment. Vienna was a bulwark against an invasion by the Turks, who had besieged the city in 1529 and 1683, with 200,000 men, and 25,000 tents; in 1532, they were fought off with the help of Ippolito de’ Medici, whom Titian immortalised in Hungarian dress to underline his command of 4,000 musketeers (fig. 3). “Bastion of the entirety of Europe” and “key to Christianity” are the definitions 22-07-2009 15. Federico Bencovich, Sacrificio di Ifigenia, Pommersfelden, Graf von Schönborn Kunstsammlungen. Federico Bencovich, Iphigenia’s Sacrifice, Pommersfelden, Graf von Schönborn Kunstsammlungen. 11:27 Pagina 59 of Vienna given by ambassadors to the capital. But who knows if the Venetian senate, on September 17, 1593, had the fortress city of Palmanova built as a defence against Islam or (which is more likely) as a bluwark against the Habsburgs, understandably worried by events at hand. Let’s not forget that, in 1500, Da Vinci had been called upon to plan a defence along the Soca/Isonzo river, as per the Codex Atlanticus (fig. 4). Leonardo Donà himself (along with Marino Grimani, Giacomo Foscarini, Marc’Antonio Barbaro and Zaccaria Contarini) was part of a commission whose brief was to define the site for a new fortress city; in 1593, he left a diary chronicling the commission's inspections (fig. 4). Y Hence, ambassadors and spies: a highly commendable profession from the days of The Art of War by Sun Tzu, a general who probably lived at the same time as Confucius in the 6th century BCE, affirmed that “going with public order to spy on what is going on in countries we look on with suspicion is a very honourable thing”; and practised by King Sargon in Mesopotamia in 2350 BCE, and not unfamiliar to Moses, who sent 12 spies into the land of the Canaanites. But the Romans were never fond of delatores, or informers; and Tomaso Garzoni called them “abominable” in Venice in 1587. The word “spy” is used in Venice for the first time in 1264, and from that moment on the Serenissima’s secret services apparatus became notorious, both domestically and abroad. The first talk of an encrypted document dates back to 1226, and there would be many subsequent uses of secret codes. And Austria was certainly no different. Just consider its infamous “Black Cabinet”, put together by Leopold i in the mid 17th century to intercept mail sent via the Turn und Taxis throughout Europe. In 1774, the bailo in Constantinople justified sending a despatch via Kotor, saying that anything sent via Vienna would be opened. The same practice was consolidated in Venice as well. Giacomo Casanova himself, as we know, was part of the Venetian apparatus. He spent a part of his exile in Vienna, and in a wonderful book on 18th-cen- context 0020.saggi.qxd 59 an historic enemy deprives the serenissima of its freedom 0020.saggi.qxd 60 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 60 tury spies, the author Giovanni Comisso writes about one of Casanova’s backbiting comments on Carlo Grimani, who “talks without any scruples whatsoever to the Russian Minister”. But perhaps Casanova’s first real spying commission was against Austria: the Inquisitors sent him to Trieste in 1773 to convince Armenian monks who had left San Lazzaro, where they had established a printing press, to return to Venice. Y Hence, ambassadors and spies. Vienna boasted a naval dockyard from which, in 1559, Ferdinand ii planned to launch 400 “nasade” with 12,000 men on board, explains Leonardo Mocenigo, even though the plan was never realised. But in 1563, 12 legni ships are ready, built by Venetian “brigands” and “bandits” with 13 to 20 “benches” (for rowers, obviously), and 150 28-futtock nassate ships. Again in 1738, the ambassador Niccolò Erizzo was particularly struck by four vessels built on the Danube thanks to the head of the Austrian navy, the marchese Giovan Luca Pallavicini. This obvious interest in Vienna’s weaponry was utterly reciprocal. In fact, while Palma was being built, despatches constantly mentioned Habsburg “explorers” who had infiltrated the ranks of the workers, and a captain disguised as a hermit was pointed out by a confidant in 1620. And Vienna, well before the Third Man (unforgettable film directed by Carol Reed, with Orson Welles and Alida Valli, 1949), had proven itself to be a city of intrigue. It was here in 1620 that an agent obtained the secret sections of the League against the Turks, and in 1628 a Spanish network in Venice was unmasked (Madrid’s Instructions were communicated to the Venetian Inquisitors). And it was in Vienna that, in 1698, the ambassador Carlo Ruzzini discovered that the Russian tsar Pietr i would travel to Venice incognito (see VeneziAltrove 2008). Even the secretary of Luigi Pio of Savoy, ambassador to Austria, was an informer, which should surprise no one considering that late-17thcentury Rome was a hive of secret activity, with even the cardinal Pietro Ottoboni, patron of Scarlatti, Corelli and Händel, and his uncle, the future Pope Alexander vii, providing confidential information, according to Paolo Preto. In the mid 18th century, the imperial ambassador to Venice received 400 sequins for his “benevolence”; at the turn of the century an abbot was also being paid for his translations of letters by the Viennese government. When needed, there were also hired killers. Venice unleashed a few in 1640 against a captain who had betrayed them and was working for the Habsburgs, and in 1662 against a gentleman who 22-07-2009 16. Giovanni Antonio Canal, detto Canaletto, La Piazza di San Marco, Vaduz-Vienna, Sammlungen des Fürsten von und zu Liechtenstein. Canaletto, St Mark’s Square, Vaduz-Vienna, Sammlungen des Fürsten von und zu Liechtenstein. 11:27 Pagina 61 worked for the city bank and had fled to Vienna with a large amount of money. Four years later, the Venetian ambassador was ordered to “remove from the world without compromising our public image” Gabriel Vecchia, guilty of “abominable acts”, and in 1754 Pietro de Vettor, from Friuli, had to be poisoned because he had stolen the secret formula for enamel and moved to the city that (Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Strauss, Schönberg, Berg, Webern) was the capital of music. Y In fact, spies also had to look after economic interests. In 1766, the secret formula for producing porcelain arrived from the ambassador to Paris before a certain baron Suter was able to deliver it to Austria. In 1733, a Bergamo knight provided information about paper mills and salt; in 1751, a spy was sent off throughout Europe (including Graz, Linz and Vienna) to collect information about tariffs, factories and trade; in 1761, the diplomat working in Vienna was asked to pay two mortar workers for their information. In 1774, spies were put to work to undermine a plan to build a road that, via Engadina, would go from Milan to Vienna; in 1620, plans were afoot to kidnap a former English corsair, who had been granted permission to “produce Venetian soaps”, but who refused to abide by the rules. In 1724, Count Rinaldo Zoppin was “persuaded” not to export to Vienna “Lotto and the game of biribìs” (one of the many games practised in the city, with very colourful names: Faraone, which was much loved by Casanova, Zecchinetta, Cressiman, Bazzica, Meneghella and Camuffo, Slipe e Slape, Picchetto, Tresette, Gilè alla Greca, Ombre, Tric Trac, Bassetta; the world “loto” was cited by Marin Sanuto in reference to a 1522 extraction; the “Genoa Lotto” first appeared in its home city in 1576 and in Venice in 1734; thanks to Italians, it was exported to Austria in 1752). In 1761, Vettor Erizzo’s plans to open a bank in Vienna were thwarted. And even the art of lace tatting had to be protected against exportation: in 1748, a lace tatter from Udine founded a plant in Vienna, with workers who had been lured from Venice. For the princely sum of 3,100 ducats he context 0020.saggi.qxd 61 an historic enemy deprives the serenissima of its freedom 0020.saggi.qxd 62 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 62 was persuaded to return to Italy before teaching his Austrian workers the art of tatting. In 1777, the ambassador to Austria helped suppress a narrative defined “reckless and detestable” by buying six copies from private sellers. Y When they weren’t busy with hired killers, diplomats described the city. They examined their fortifications, the state machine (“a body without any organisation”, wrote Michiel in 1678) and their weaponry (in 1769, Paolo Renier, future doge, wrote of “country canons” able to fire 15 shots per minute, and of one with case shot able to fire cannon balls to a distance of 400 paces). But in 1793, Daniele Dolfin paid homage to Joseph ii for his concession of religious freedom and for abolishing slavery in the form of serfdom, even if there was still “dissatisfaction in the provinces” with their disparate ethnicities, and efforts to homogenise the country seemed vain. Ambassadors, however, were also expected to give gifts. The ambassador Donà, for example, was asked by the archduke Ferdinand to provide, for his own historical armour collection, the armour worn at Lepanto by Doge Sebastiano Venier, Agostino Barbarigo (who was killed in battle) and Marcantonio Bragadin (flayed at Famagosta), “and wanted that we commit this to writing, as we did to Your Most Serene Highness”. Communication between the two cities had been very intense for quite some time. Postal services between the two had begun in 1558, when the Polish king Sigismund ii linked his dominions with some of his southern capitals, and the postal service betweenVenice and Vienna was among the first to be established. Y But those itineraries were not only being frequented by ambassadors and spies, in either direction. No one perhaps as much as the Germans (in the term’s broadest sense) has loved or desired Italy more, and above all Venice, which they discovered well before Goethe. The Germans had their own Fondaco, next to Rialto and frescoed by Titian and Giorgione, in Venice from the Middle Ages. The Fugger bankers were extremely important, and it is thanks to them that Albrecht Dürer was brought to Venice to create his Festival of the Rosary altarpiece for the church of San Bartolomeo (1506). The altarpiece is two meters wide and is full of authentic portraits, including those of the current Pope and Em- 22-07-2009 17. Joseph Haunzinger, L’imperatore Giuseppe II con le sorelle Anna ed Elisabetta; lo spartito è di un Duo di Antonio Salieri. Joseph Haunzinger, Joseph II of Habsburg with his Sisters Anna and Elisabeth; the music is Antonio Salieri’s Duo. 11:27 Pagina 63 peror, the painter himself, the Fondaco architect and the commissioner (figs. 7, 8). In 1606, Rudolf ii demanded it be brought to Prague. But these were still just generically “todeschi”, or “Teutons”, and not Austrians. The Fuggers were from Augsburg, and began as merchants and bankers in the 15th century before they became firmly established in the 16th (they leant Maximilian i 150,000 florins, contributed 500,000 florins for the election of Charles v in 1519, and had other offices in Rome); as Germans, they were the first artists from “beyond the alps” and the west in Venice. Including Giovanni d’Alemagna (literally “from Germany”) who, in 1446, with his brother-in-law Antonio Vivarini, painted the first painting on canvas ever recorded in Venice for the Sala dell’Albergo in the church of Santa Maria della Carità (fig. 9). The painting is a polyptich (on linen), three and a half metres tall and almost five metres wide, the work of trend-setting titans, where the delicate brocades indicate a complex technique that was certainly based on careful observation of foreign artists. Then trips and contributions in both senses became all the more common, finally involving Austria and Vienna itself, which was just beginning to emerge as a capital. Pietro Liberi (1605-87) worked there, and Leopold i made him count; in the mid 17th century, Marco Boschini dedicated his Carta del navegar pitoresco to the archduke Leopold Wilhelm. Others who worked there were Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini (1675-1741, fig. 10) and Sebastiano Ricci (1659-1734, figsa. 1, 11), who was in Schönbrunn at Johann Carl Loth’s along with Johann Michael Rottmayr (1654-1730), who had studied in Venice for 11 years (as had Hans Johann Rottenhammer, from Munich, a century earlier). Loth himself was born in Munich in 1652, and died in Venice, his second homeland, in 1698. He received commissions from all the European courts, and exported the fad for sketches from Italy. Y After which, there were no limits to the comings and goings. Palazzo Liechtenstein holds paintings by Antonio Bellucci (16541726), whose only work still in Venice is a San Lorenzo Giustiniani (the first Patriarch) at the church of San Pietro di Castello (until 1807 the city’s cathedral), and one of whose studies for the Slaughter of the Innocents was recently put on auction by Sotheby’s for an estimated 9,000 euros, but remained unsold (fig. 12). Simon Vouet’s nephew, Louis Dorigny (1654-1742), a Parisian who had adopted Venice and the Veneto, decorated the Rotonda in Vicenza, Villa Manin in Passariano and the Duomo in Udine; in Vienna he fres- context 0020.saggi.qxd 63 an historic enemy deprives the serenissima of its freedom 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 18. Giovanni Battista Lampi, Ritratto del principe Johannes I von un zu Liechtenstein, Vaduz, Kunstsammlungen des Fürsten von Liechtenstein. Giovanni Battista Lampi, Portrait of Prince Johannes I von un zu Liechtenstein, Vaduz, Kunstsammlungen des Fürsten von Liechtenstein. 19. Anonimo, Antonio Vivaldi, Bologna, Museo internazionale e Biblioteca della musica. Anonymous, Antonio Vivaldi, Bologna, Museo Internazionale e Biblioteca della Musica. 64 11:27 Pagina 64 coed the home of Eugenio of Savoy, who was at the time the most famous of the condottieri. Daniele Antonio Bertoli (1677-1743) was chamber decorator to Joseph i, Charles vi and the young MarieThérèse, whose teacher he had been. The imperial family and Viennese aristocrats then asked that their portraits be undertaken by Rosalba Carriera (1675-1757), Pellegrini’s sister-in-law, who also began a series of Four Seasons which she also undertook for the English consul Joseph Smith. Bernardo Bellotto (1721-80), on the other hand, painted countless scenes of the capital (figs. 13, 14) commissioned by Marie-Thérèse. Franca Zava Boccazzi writes of the incredible life of Federico Bencovich (?1677-1756), a Dalmatian brought to Venice by a musical relative and sent to study with Carlo Cignani, active in Schönbrunn and Würburg, who would be the young Giambattista Tiepolo’s model for the Residenz cycle (fig. 15). Unfortunately, what little remained of his work was destroyed during world war two. Our overview comes to an end with Giovan Battista Pittoni (1687-1767), active in Schönbrunn and elsewhere, and the 13 Canalettos the Liechtenstein’s added to their collection, which returned to Vienna only recently from Vaduz (fig. 16), where it had been taken on the eve of the last world war. Y Even more intensive were the musical and literary worlds, that others will be writing about. In the 16th century, Viennese music was not brilliant, nor particularly memorable, and it is maintained that for Ferdinand ii’s wedding to Eleonora Gonzaga, the first chapel maestri were brought in from Venice. Giovanni Priuli (1575-1629) and Giovanni Valentini (1583-1649) studied with Giovanni Gabrieli, and died in Vienna; Ferdinand iii was crowned to the strains of Monteverdi’s Ballo delle ingrate; Antonio Bertali from Verona (1605-69), who taught music to the heir to the throne, also died in Vienna; the relatively unknown Giovanni Felice Sances (1600-79) directed the chapel until his death. Great cultural mediators in Vienna at that time included the reformers of the melodrama Apostolo Zen (who was born and died in Venice, 1668-1750), who wrote 66 libretti and was Caesarean poet for ten years from 1718, and Pietro Metastasio (born Trapassi; b. Rome 1698 – d. Vienna 1782), who followed Zen with a salary of 3,000 florins per annum, but who moved to Austria, where he lived on the 4th floor at 12 Kohlmarkt, “only after the Venetian verification of his texts” (Giovanni Morelli). At 12 he was translating the Iliad into octaves, and he wrote 27 musical dramas, 35 theatrical pieces, 8 oratorios, serenades, lyrical poems and songs. He 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 65 was commissioned by many in Venice, including the Tron, Soranzo Gradenigo and Tiepolo families, and staged many of his premiers there. When he left Italy, he had already been successful in Venice with his Artaserse, Siroe and Didone abbandonata. Artaserse was set to music by Leonardo Vinci and Johann Adolf Hasse (who died in Venice in 1783). It was first performed in 1730 in Rome, at the San Giovanni Crisostomo theatre. As a sign of its popularity, it would later be taken up again by 85 other authors, including Gluck, Scarlatti, Johann Christian Bach, Galuppi, Paisiello and Cimarosa. Siroe was, once again, set to music by Vinci, was performed in Venice in 1726, and was taken up again by another 20 musicians, including Vivaldi, Handel, Scarlatti, Galuppi and Piccinni. Didone was set to music by Domenico Natale Sarro, who presented it in his native Naples in 1724, but it became a success when it was later performed in Venice by Tomaso Albinoni in 1725. It was so successful, in fact, that the original author worked on a remake for Venice in 1730, and in all 57 musicians adopted it, up to Saverio Mercadante in 1823. Metastasio debuted in Austria on November 4, 1731, the day of Charles vi’s name-day, with Demetrio by Antonio Caldara (Venice 1670-Vienna 1736), and, according to the perfidious Lorenzo Da Ponte, he died there of a broken heart when he was told that his pension had been suspended. Among the works by the last of the Habsburg chapel maestri from Venice, Antonio Salieri (Verona 1750-Vienna 1825), there are, strangely enough, Metastasio’s Semiramide and Il pastor fido, based on a libretto by Da Ponte, and where, according to Sandro Cappelletto, Mozart was conducted. Salieri arrived in Vienna following the Bohemian Florian Leopoldo Gassmann (172974), who, after his father Martini’s famous school in Bologna, worked for the Veneri counts in Venice, whence he was called to follow Gluck at the Burgtheater. After the accidental death of his mentor, Salieri taught his daughters music and replaced him as Hofkapellmeister (fig. 17). Y Until then, many Venetians had wielded a conductor’s baton at context 0020.saggi.qxd 65 an historic enemy deprives the serenissima of its freedom 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 20. Manifesto della prima Biennale d’Arte, 1895, Venezia, collezione Fondazione di Venezia. Placard for the first Biennale d’Arte, 1895, Venice, Collezione Fondazione di Venezia. 21. Gustav Klimt, Giuditta II - Salomè, 1909, Venezia, Galleria internazionale d’Arte moderna di Ca’ Pesaro. Gustav Klimt, Judith II (Salomé), 1909, Venice, Galleria internazionale d’Arte moderna di Ca’ Pesaro. 66 11:27 Pagina 66 the Viennese court, where the streets “are paved with culture, while in other cities they are asphalt” (Karl Kraus). In 1640, one such was Francesco Cavalli (originally Pier Francesco Caletti-Bruni, 1602-76) from Crema who at the age of 15 was already a singer at St Mark’s, where he would remain. He had undertaken only one trip to Paris, on the invitation of Cardinal Mazzarino, for an opera to be performed for the marriage of Louis xiv, the Sun King, to Margaret of Austria, daughter of Philip iv of Spain, in 1660, but the theatre wasn’t ready and the play was put on two years later. He was followed by Marc’Antonio Ziani (16531715) and Carlo Agostino Badia (1671-1738), who both died in Vienna, as did Antonio Draghi (1634-1700 – Draghi was born in Rimini but educated in Venice), and, from 1714, by Antonio Caldara (3,500 compositions; at the time he was considered the best there was in the field of Austrian music, along with Antonio Lotto, who was also Venetian [16661740] and had debuted as singer at St Mark’s; with Caldara Veneto supremacy in baroque musical theatre arguably comes to an end). Yet another is Antonio Pancotto, who was so memorable he was ignored even by Deumm, the music-lovers’ “bible”. Y Baldassarre Galuppi was a guest when his Demetrio was performed, based on Metastasio. (Giovanni Battista Lampi, originally from Trent but who had studied in Verona, experienced his greatest fame here and St Petersburg as an official portrait artist, for which he was much in demand by the most important royalty of the time, fig. 18). And, finally, Dominco Barbaja (impresario for Naples’ San Carlo theatre, the An der Wien theatre and the Kätnerthortheater) called to Vienna Gioachino Rossini, who had provided ten works premiered in Venice’s San Moisè theatre between 1810 and 1823. (On a completely unrelated side note, in 1742, Carlo Ginori, creator of the historic Doccia porcelain and majolica, arrived in Venice to ask Giovanni Vezzi for advice, only to end up in quarantine on the island of Lazzaretto Nuovo.) Antonio Cesti (Arezzo 1623-69), who would later make his fame and fortune in Innsbruck, debuted at the Santi Apostoli in 1649. He was 0020.saggi.qxd 24-07-2009 10:52 Pagina 67 an historic enemy deprives the serenissima of its freedom 0020.saggi.qxd 68 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 68 one of the most prolific authors of the period, and was much admired by Salvatore Rosa in 1652 (“In Venice he has become immortal and admired, the best musical composer at the moment”). And it was in Vienna that Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741, fig. 19) mysteriously spent his last and most certainly poverty-stricken days. He had gone to Vienna with his father in 1730 for the performance of Farnace, but had already composed the music for the weddings of Louis xv and Charles vi, to whom he dedicated a musical homage in Trieste and who made him a knight of the realm. And perhaps he wanted to meet him again. No longer as admired as he once was in Venice, and thwarted in Ferrara (the cardinal Fabrizio Ruffo refused to allow him to perform one season, officially “because of his friendship with the singer Girò”), he left in 1740. But things weren’t looking good: Charles vi died, war broke out, and he sold his manuscripts for as much money as he could muster. He lodged at a widow’s, near the theatre where he hoped to put on some performance (the home was destroyed in the 19th century, now replaced by the Sacher hotel). It was here that he died on the night of July 27, 1741. There is now a small plaque near the Karlskirche (the vault of which is frescoed by Rottmayr, who introduced the Venetian sketch to the rest of Europe) to remind us that he is buried there, in a common grave. And what became of his music, the more than 550 concerts (once, according to De Brosses, he boasted he had composed one faster than the copyist could write it out)? It was forgotten until the 20th century. In the centre of Vienna, in Rooseveltplatz, for the 260th anniversary of his death, a small monument by the Venetian Gianni Aricò was unveiled: three Carrara marble figures representing his “Putte”. Y The rest (and there is tons more) we will have to deal with very cursorily. Thanks to Bernardo Bellotto, we know what the city of the Habsburgs was like at the time. Canaletto’s nephew debuts with a scene commissioned in 1759 by Prince Wenzel Anton von Kaunitz-Riethberg (the prince was also famous for commissioning, in those difficult times, a chapel with a pulpit for catholics and one for protestants); he then immortalised three castles (the third is Schönbrunn), two of which (Belvedere and Schlosshof) formerly belonged to Eugenio of Savoy, as well as squares and markets; Marie-Thérèse also bought many of his works. Y Many of the Venetian masterpieces in Charles i’s collection found their way to Vienna after he was beheaded. In 1798, while he was in the Habsburg capital pressing for his annuity, Canova 22-07-2009 22. Romaine Brooks, Gabriele D’Annunzio, il poeta in esilio, 1912, Parigi, Musée National d’Art moderne (in deposito a Poitiers), dono dell’artista, 1914. Romaine Brooks, Gabriele D’Annunzio, Poet in Exile, 1912, Paris, Musée National d’Art moderne (Poitiers deposit), gift of the artist, 1914. 11:27 Pagina 69 was commissioned to provide a funeral monument for Marie Cristina of Austria, which has been in the Augustinerkirche since 1805. And soon, Venice would be singing the praises of a portrait artist who arrived from Vienna and died in a Venetian calle: Ludwig Passini (1832-1903) lived in Rome and left behind a splendid View of the Caffè Greco, but he spent his last 30 years in Venice, living in Palazzo Vendramin dei Carmini where, in 1895, along with Alma Tadema, Puvis de Chavanne, Gustave Moreau and Edward Coley Burne-Jones, he was part of the Committee for the first Venetian Biennale, fig. 20, (the second Biennale would exhibit one of his portraits). The young Gustav Klimt (1862-1918), who debuted at the age of almost 20 when he and his brother Ernst (two years younger than him!), along with his fellow student Franz Matsch, decorated the municipal theatre in Fiume, frescoed the stairwell at the Kunsthistorisches Museum and, between Greek and Egyptian art, he painted his Italian Renaissance. The Sezession was still a long way off, and even further off was the tribute the Biennale would pay him in 1910 by dedicating an entire exhibition to him. Venice would also eventually purchase his Judith (fig. 21). Y Our last two titbits are also from the 20th century. The two cities are also in some way linked by Gabriele D’Annunzio. The flight over Vienna on August 9, 1918 (11 Ansaldo Svas from the 87th squadron) was under the aegis of St Mark (the name of the squadron commanded by D’Annunzio, fig. 22) and the Serenissima, which was the title of the 87th squadron. Take off, which included the ace aviator Arturo Ferrarin, took place from Campo San Pelagio, at the doors of Padua. Of the eleven planes that left, seven arrived at Vienna, dropping 50,000 copies of a manifesto written by D’Annunzio himself onto the city. Finally, during the Belle Époque, the mythical Simplon Orient Express also provided a bridge between the two cities. The train has recently been reinstated, with 12 blue wagons-lit built between 1926 and 1931, but it is not for everyone: the Venice-Vienna trip in luxury suite will set you back 1,600 euros per person. context 0020.saggi.qxd 69 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 70 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 71 dal ’700 fin quasi al 2000: l’attrazione e la ripulsa la laguna come un’alterità a portata di mano. e poi, il mito della città morta Andrea Landolfi 1. August Friedrich Pecht, Dopo la resa di Venezia nell’anno 1849, 1854 (particolare), Praga, Národní Galerie. August Friedrich Pecht, Following Venice’s Surrender in 1849 (detail), 1854, Prague, Národní Galerie. Y «Il sacrificio della patria nostra è consumato: tutto è perduto; e la vita, seppure ne verrà concessa, non ci resterà che per piangere le nostre sciagure e la nostra infamia». Così, nel celeberrimo incipit dell’Ortis, Ugo Foscolo dà voce alla propria disperazione, all’indomani di quell’abominato trattato che, di fatto, sancisce la fine della gloriosa indipendenza di Venezia, ceduta, anzi, svenduta da Napoleone agli odiati Austriaci (figg. 1, 13). Il lettore curioso, che desiderasse mettere accanto a quelle parole e a quello stato d’animo un prodotto di segno contrario, un inno celebrativo della nuova Venezia austriaca (fig. 2), se anche cercasse a lungo non troverebbe che trascurabili (letterariamente parlando) echi di gazzette. È come se quei quasi nove anni di Venezia “austriaca”, e il cinquantennio che di lì a poco seguirà, mancassero di un connotato; è come se la letteratura avesse rinunciato programmaticamente, in quel caso, alla propria funzione esornativa, a far sentire la propria voce sul dato storico immediato. Perché? Y Nell’immaginazione poetica e letteraria dell’Europa, Venezia fa il proprio ingresso nel momento della parabola discendente: quando, ormai esausta, la Serenissima va inesorabilmente avvicinandosi all’appuntamento con la storia che tanto strazierà Foscolo e la sparuta élite intellettuale in grado di identificarsi nel suo romanzo (fig. 3). È nel Settecento che al mito della città dei traffici e delle ricchezze favolose (fig. 4) si sostituisce, a poco a poco, la presa d’atto di una grandezza ormai trascorsa, icasticamente rappresentata dai grandi palazzi in abbandono, con le assi di legno malamente inchiodate a chiuderne le finestre ormai prive di vetrate (fig. 5), e ipostatizzata nell’essenza stessa della città, fluttuante sull’acqua e priva di un solido radicamento nel suolo. Ed è proprio la mancanza di fondamenta a rendere Venezia unica e straordinaria non solo nel novero delle città del mondo, ma anche, ed è ciò che più conta per noi, nell’immagine “psicologica”, se si può dir così, che della ex Regina dei Mari si i libri, i poeti 0020.saggi.qxd 71 dal ’700 fin quasi al 2000: l’attrazione e la ripulsa 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 2. Vincenzo Chilone, Regata in Canal Grande per i sovrani austriaci, Venezia, collezione Treves Bonfili. Vincenzo Chilone, Regatta on the Grand Canal for the Austrian Sovereigns, Venice, Collezione Treves Bonfili. 3. Francesco Jacovacci, L’ultimo Senato della Repubblica di Venezia, Roma, Galleria nazionale d’Arte moderna. Francesco Jacovacci, The Last Senate of the Venetian Republic, Rome, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna. 72 11:27 Pagina 72 sono creati poeti e scrittori. Ciò che da Goethe in poi di Venezia si celebra, ciò che di Venezia irresistibilmente attrae, è la sua sostanziale inappartenenza alla terraferma della realtà comune, e quindi alla storia; di questa essenza obliosa due grandi ingredienti mitici si fanno garanti: l’acqua, appunto, e la maschera (fig. 6). Y Dai suoi due soggiorni veneziani, l’uno del 1786 e l’altro del 1790, Goethe (fig. 7) trae una doppia immagine della città, che detterà la norma a tutta la letteratura a venire, specie a quella di lingua tedesca. L’infinitesimo lasso di tempo tra l’una e l’altra permanenza spalanca in realtà, per il poeta e dignitario di un microscopico stato della Germania assolutista, un abisso epocale tra un prima della sicurezza e dell’ordine del mondo, e un dopo dell’incertezza e del disordine. Irritato, più che impaurito, da quella Rivoluzione francese di cui pure, stando a Thomas Mann, era stato tra i promotori con il suo Werther, Goethe affianca alla Venezia solare del Viaggio in Italia, perlustrata e descritta con amoroso zelo, quella piovosa, sudicia, corrotta e malfida degli Epigrammi veneziani, stabilendo una volta per tutte, con l’autorevolezza che gli è propria, le due coordinate fondamentali del rapporto della grande letteratura, di lingua tedesca e non solo, con la città: l’attrazione e la ripulsa. Ciò che nella considerazione di Venezia è mutato, ancora al di qua degli eventi che condurranno alla perdita dell’indipendenza, è il dato di atmosfera: gli stessi veneziani, osservati dal Goethe del 1790 con sguardo disilluso e profetico, sembrano accompagnare la fine della loro grande storia con torpida indifferenza, contribuendo ad attribuire alla città quello statuto di extraterritorialità ed extratemporalità, di sostanziale, intima estraneità alle vicende non solo della storia, ma addirittura della vita reale, di cui si diceva. Questa sorta di trasfigurazione onirica, che àncora la città sul fondo melmoso di un passato dai contorni indistinti, di una grandezza la cui cifra essenziale è nel suo essere irrimediabilmente trascorsa, costituisce l’elemento caratteristico del rapporto della letteratura europea con Venezia: nasce da qui, da questa navigazione labirintica attraverso e contro la storia, il mito della Venezia decadente; del simulacro; della città morta. Y Ma il rapporto degli scrittori e poeti austriaci con Venezia si arricchisce e si complica di un dato ulteriore, che pur non avendo, come si vedrà, immediata attinenza con le vicende storiche, tuttavia ne deriva: è il senso profondo di un’intima affinità, 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 73 un’appartenenza nativa, metastorica. Per tutto il Settecento, e fino alla Rivoluzione francese, Venezia rappresenta per l’Austria la sponda felice di un’alterità a portata di mano: dove gli intensi rapporti commerciali si nutrono anche dell’atmosfera di libertà (e libertinaggio) della città del carnevale e del gioco d’azzardo. È l’altra faccia, appunto quella in maschera, della Venezia degli Epigrammi di Goethe: è la città dell’edonismo, la città madre di quel Giacomo Casanova che, non a caso, trova la consacrazione mitico-letteraria proprio grazie agli austriaci Hofmannsthal e Schnitzler, e proprio quando, sotto i colpi dei diversi nazionalismi, inizia a scricchiolare l’immensa impalcatura dell’impero austroungarico. Allora, per gli scrittori diventa ineludibile proiettare sulla “gaia apocalisse” veneziana i prodromi e i timori di quella asburgica (fig. 8). Y Prima di quei tempi, esattamente come quella degli inglesi, francesi e tedeschi, la Venezia degli austriaci è semplicemente veneziana; e poco importa il sistema che la governa. Che la città in cui Franz Grillparzer soggiorna nel 1819 sia di nuovo, e da pochi anni, politicamente “austriaca”, è un dato incidentale, che lo scrittore nemmeno registra nel suo diario; ciò che viceversa annota è l’emozione provata dinanzi a quella che definisce «storia pietrificata»: la vista del Ponte dei Sospiri gli detta una pagina commossa sulla turpe, futile e sanguinosa vicenda della storia umana, scandita da stragi e sopraffazioni che, al di là del dolore, non lasciano alcuna traccia durevole. Non una parola sul presente, sul governo della città; in compenso, una colorita annotazione sulla bellezza, e sulla capacità di goderne: «Chi, trovandosi per la prima volta in Piazza San Marco, non si senta balzare il cuore nel petto, corra a farsi scavare la fossa: sarà, infatti, indubitabilmente morto» (fig. 9). Y Risale invece ai primi anni Sessanta la novella La casa al Ponte i libri, i poeti 0020.saggi.qxd 73 22-07-2009 dal ’700 fin quasi al 2000: l’attrazione e la ripulsa 0020.saggi.qxd 4. Gustav Klimt, Quattrocento romano e veneziano, 1890-1891, pennacchi e intercolumni, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, olio su stucco. Gustav Klimt, Griechische und römische Antike Übertragungsskizzen zu den Zwickel- und Interkolumnienbildern im großen Stiegenhaus, 1890-1, oil on stucco. 74 11:27 Pagina 74 della Verona di Friedrich Halm, quasi dimenticato contemporaneo e “rivale” di Grillparzer, in cui Venezia fa da fosco scenario a un dramma d’amore che culmina nel suicidio del protagonista. Di maniera, anche se non priva di fascino, la Venezia cinquecentesca vi è rappresentata secondo stilemi che oggi definiremmo noir e che risalgono al romanzo di Schiller Il visionario, capostipite di un sottogenere che troverà in Morte a Venezia di Thomas Mann il proprio capolavoro. Anche in questo caso salta all’occhio, considerando oltretutto l’orientamento legittimista di Halm, la mancanza di qualsiasi accenno alla Austriazität di Venezia: d’altra parte, assente anche nella novella di Ferdinand von Saar Seligmann Hirsch, del 1880, in cui la città è vista come il malinconico luogo dell’abbandono e della solitudine dove il protagonista, un ricco ebreo rovinatosi per la passione del gioco, è bandito dai figli e dove troverà la morte. Qui Venezia, ben lungi dall’essere rappresentata come “austriaca”, è vista addirittura come luogo di esilio: fatto davvero curioso, se si considera che Saar, il quale aveva servito da imperialregio ufficiale in uno dei reggimenti misti reclutati nelle Venezie, parlava correntemente l’italiano e dell’Italia, e in particolare della città lagunare, aveva un’approfondita conoscenza (fig. 10). Y Su un terreno più frivolo e lieve, ma non per questo meno gravido di conseguenze nella costruzione, ormai non più politica ma decisamente nostalgico-sentimentale, di una Venezia “austriaca”, va ricordata l’operetta di Johann Strauss Una notte a Venezia, del 1883, il cui libretto, opera di Friedrich Zell e Richard Génée, reinterpreta in chiave moderna il mito settecentesco del luogo del carnevale e della gioia di vivere, speziandolo con un esotismo addomesticato e ormai alla portata della borghesia: da 22-07-2009 5. Palazzo Cicogna all’Angelo Raffaele, nel 1855, in una fotografia di Domenico Bresolin, Venezia, collezione Zannier. Palazzo Cicogna all’Angelo Raffaele, in 1855, in a photograph by Domenico Bresolin, Venice, Zannier collection. 11:27 Pagina 75 icona letteraria, la città prende a trasformarsi in destinazione turistica, meta privilegiata del “viaggio di nozze”. È in quell’atmosfera che pochi anni dopo, nel 1895, s’inaugura a Vienna, con grande clamore, quello che sembra essere stato il primo parco di divertimenti a tema della storia. Si chiamava Venedig in Wien, ed era una ricostruzione fedele, con tanto di calli, ponti, canali e facciate di palazzi storici, di una Venezia “pittoresca” a uso delle famiglie. Ormai a trent’anni dalla fine della dominazione austriaca, la città, che nella sensibilità comune era rimasta sempre e soltanto se stessa, entra prepotentemente a far parte dei grandi miti popolari, e proprio a Vienna sperimenta un assaggio di quello che sarà il suo destino novecentesco: la banalizzazione, la riduzione a cliché, a simbolo per eccellenza del moderno turismo di massa. Malinconico e solitario frequentatore di Venezia, quella vera, il grande Peter Altenberg descrive in uno dei suoi fulminanti Estratti della vita quel trionfo di moderna inautenticità che sembrava aver stregato i suoi concittadini (anche se per poco, visto che già cinque anni più tardi l’impianto è smantellato); nella finta Venezia viennese c’è proprio tutto: dai «gondolieri, che nel canale manovrano con destrezza e si comportano in modo cavalleresco», alle «trentamila persone che vanno su e giù per le piazze e si assiepano sui ponti», fino alle coppie che si aggirano nella città virtuale fingendo a se stesse emozioni e trasporti, appunto, da “notte a Venezia”… Y Ma negli stessi anni un’altra Venezia, neppure lontanamente sfiorata da quel processo di progressiva appropriazione e banalizzazione di cui si è detto, si affaccia nelle pagine di uno scrittore austriaco. Il suo creatore la descrive come «la città più bella del mondo», e comunica ai lettori l’impressione di una specie diversa e nuova: non più l’angoscia dell’insidia e della perdizione, e nemmeno l’entusiasmo a buon mercato della gioia di vivere; piuttosto l’emozione della scoperta, lo sgomento gioioso della prima volta. In questo senso si può dire che la Venezia di Hu- i libri, i poeti 0020.saggi.qxd 75 dal ’700 fin quasi al 2000: l’attrazione e la ripulsa 0020.saggi.qxd 76 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 76 go von Hofmannsthal è davvero la prima e unica Venezia “austriaca” che possediamo (fig. 11): senza bisogno di alcun processo di appropriazione, Hofmannsthal semplicemente riconosce nella città una felice patria del cuore, luogo dell’anima e della vita che è suo per una sorta di appartenenza ancestrale, di là da ogni contingenza storica. Non diversamente da quella di tanti predecessori e contemporanei, anche la Venezia in cui giunge il giovane protagonista del romanzo Andrea o i ricongiunti (composto tra il 1907 e il 1913, incompiuto e pubblicato postumo nel 1930) è notturna e infida; e anch’egli si imbatte in figure inquietanti, dall’identità mutevole e dalle intenzioni oscure; solo che, per lui, l’immersione nel disordine non avviene sotto l’egida di una tenebrosa istanza di perdizione, come negli stessi anni sarà per l’Aschenbach di Thomas Mann, bensì nel segno felice di un cammino verso la luce, la maturità e la ricomposizione. Presenza ricorrente nell’opera del poeta fin dal 1892, l’anno della Morte di Tiziano, la città è per Hofmannsthal luogo privilegiato dove situare avventure il cui esito è una svolta esistenziale positiva, una scelta per la vita, una tensione verso una possibile felicità, il punto cruciale dove l’anima sperimenta la massima concentrazione e attinge la verità del proprio destino, il senso della propria vocazione nel mondo. Questo trova la propria celebrazione in un racconto del 1907 intitolato Ricordo di giorni belli: in esso, l’emozione visiva del rivelarsi della città nello splendore del crepuscolo trapassa in quella della rivelazione della propria creatività come di un potere immenso, quasi divino, la cui immane empietà può essere emendata soltanto con la devozione assoluta a un compito umano. Appena accennato nel racconto, tematizzato in pagine indimenticabili nell’Andrea, il luogo di quel compito, di quel servizio d’amore che dà sostanza alla vita, non sarà più Venezia, città dell’intuizione abissale, ma la stazione intermedia del viaggio sulla via del ritorno a Vienna: la purezza cristallina dei monti e delle valli della Carinzia, la limpida superficie in cui, redenta, può finalmente celarsi la profondità. Y Tutt’altra Venezia, desolata e oppressa da un cielo fosco e caliginoso, sporca e trasandata, è invece quella che, come uno specchio impietoso, accoglie il Casanova di Schnitzler (fig. 12). Nella novella intitolata Il ritorno di Casanova e pubblicata subito dopo la fine della Prima guerra mondiale, lo scrittore proietta sul grande personaggio veneziano, già protagonista di due commedie giovanili dell’amico Hofmannsthal, il senso di sgomento e di 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 77 i libri, i poeti 0020.saggi.qxd 6. Joseph Mallord William Turner, Il Canal Grande con Santa Maria della Salute dall’Hotel Europa, 1840, collezione privata. Joseph Mallord William Turner, The Grand Canal, with Santa Maria della Salute from Hotel Europa, 1840, private collection. perdita di fronte all’inarrestabile, e cieco incalzare del tempo e della storia (figg. 1, 13). Non troppo diversa nelle atmosfere, la Venezia descritta nel 1928 da Franz Werfel nel romanzo Verdi emenda in qualche misura questa sua Stimmung cupa e malinconica, facendone il contrassegno del difficile cammino che porterà il musicista italiano a ritrovare la propria vocazione proprio nell’incontro con la musica “veneziana” (il Tristano) dell’eterno rivale Wagner. Il binomio Venezia-musica, già adombrato dal tedesco Platen e tematizzato in un celebre detto di Nietzsche («Se cerco un altro termine per “musica” trovo sempre e soltanto “Venezia”»), è anche la cifra nascosta della laguna di Rainer Maria Rilke: il poeta, che soggiorna a più riprese in città tra il 1897 e il 1920, vi scorge ovunque «sinfonie di colori» che ne sottolineano l’evanescenza, il non essere; «[...] la città che sempre, ove un barbaglio / di cielo si franga nell’acqua alta, / senza mai essere, si forma» (Mattino veneziano, 1908). Colori e suoni si sovrappongono e si confondono in un’unica sensazione che, ancora una volta, rimanda a una perdita, a una caduta: «La città più non fluttua come un’esca / che catturi ogni giorno al suo apparire; / come vetro infranto risuonano i palazzi / al tuo sguardo. 77 22-07-2009 dal ’700 fin quasi al 2000: l’attrazione e la ripulsa 0020.saggi.qxd 7. Karl Bennert (da Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein, 1787), Johann Wolfgang Goethe nella campagna romana, Francoforte, Goethe-Museum. Kark Bennert (from Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein, 1787), Johann Wolfgang Goethe in the Roman Countryside, Frankfurt, Goethe-Museum. 78 11:27 Pagina 78 E ai giardini l’estate / si appende come una marionetta / a testa in giù, stremata, uccisa» (Tardo autunno a Venezia, 1908). Y Un’affinità prossima all’identificazione, per intensità non diversa da quella vissuta da Hofmannsthal, è invece caratteristica del rapporto che lega alla città Theodor Däubler, austriaco cresciuto a Trieste. Decisiva nell’adolescenza del poeta, come lui stesso dice («[...] senza Venezia mi sarei perduto»), l’esperienza in laguna diventa una sorta di mito personale, il luogo felice della compiutezza e della rivelazione dell’eros: «Più grave diviene la sera, più imponente la città. / È come se Dioniso aleggiasse su noi. / La laguna ai suoi piedi, simile a una pantera» (La luce del nord, 1921). Y Ma con l’irruzione del turismo di massa e del consumismo culturale, anche il mito di Venezia, a partire dalla seconda metà del Novecento, si appanna e ripiega su se stesso, perdendo inesorabilmente smalto, carattere e originalità. Difficile, se non impossibile, trovare a questo punto testimonianze di un rapporto vivo e autentico con la città, a meno di non prendere atto coraggiosamente del nuovo stato delle cose. È quello che fa, con un romanzo amaro e provocatorio, Gregor von Rezzori nel 1986: nel suo Disincantato ritorno, ambienta in una Venezia stravolta da orde di turisti la vicenda patetica di una coppia di austriaci semi-colti, intenti a “consumare” cultura in una ridda insensata di visite ai musei cittadini, nel tentativo inane di colmare il vuoto desolato della loro vita. Così, con lo scrittore che Claudio Magris definisce l’ultimo rappresentante del mito asburgico, la città-simbolo di una millenaria tradizione di civiltà si tramuta, come in uno specchio deformante, nella propria caricatura: nella triste insegna dell’immedicabile inautenticità del nostro tempo. 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 79 from the 18th to the late 20th centuries: attraction and repulsion the lagoon as proximate alterity. and the myth of the dead city Andrea Landolfi Y “The sacrifice of our homeland is complete. All is lost, and life remains to us – if indeed we are allowed to live – only so that we may lament our misfortunes and our shame.” In this famous opening to The Last Letters of Jacopo Ortis, Ugo Foscolo gives voice to his own desperation the day after the signing of the abominable treaty that officially sanctioned the end of Venice’s glorious independence – an independence that Napoleon gave (or, actually, sold on the cheap) to the despised Austrians (figs. 1, 13). The curious reader who might want to compare these words with those reflecting an opposite state of mind, a celebratory hymn to the new, Austrian Venice, would be hard pressed to find anything other than (literarily) minor echoes in a few gazettes. It’s as if those nine years of “Austrian” Venice (fig. 2), and the fifty years that were soon to follow, were missing an important element, as if literature had decided, as a matter of policy, to relinquish its ornamental function in order to lend its voice to an immediately pressing historical fact. Why? Y In Europe’s poetic and literary imagination, Venice made its entrance at the moment of its waning, when, exhausted, it was inexorably moving towards that appointment with history that was to have such a devastating effect on Foscolo and the small coterie of intellectuals who identified with his novel (fig. 3). And it was in the 18th century that the myth of the busy, fabulously wealthy city (fig. 4) was slowly substituted by the awareness that its greatness had already passed, a greatness that was now vividly represented by its magnificent yet nonetheless abandoned palazzi, with its glassless windows hastily boarded up (fig. 5), the city itself hypostatised in its very essence, and that is by floating on water deprived of a solid earthly rooting. It is this lack of foundation that made Venice unique and extraordinary not only among world cities, but also (and this is what most matters to us) in the “psychological” image (for want of a better definition) that poets and writers had wrought of the former Queen of the Seas. What books, poets 0020.saggi.qxd 79 from the 18th to the late 20th centuries: attractions and repulsion 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 8. Giuseppe Bernardino Bison, Piazza San Marco con i soldati austriaci, collezione privata. Giuseppe Bernardino Bison, Austrian Soldiers in St Mark’s Square, private collection. 9. John Ruskin, Palazzo Ducale, capitelli della loggia (matita e acquerello), 1877, Sheffield, Ruskin Gallery, The Guild of St. George Collection. John Ruskin, Ducal Palace, Renaissance Capitals of the Loggia (pencil and watercolour), 1877, Sheffield, Ruskin Gallery, Guild of St George Collection. 80 11:27 Pagina 80 authors from Goethe on celebrate about Venice, what is irresistibly attractive about Venice, is its substantial non-affiliation with the mainland of common reality, and therefore of history; there are two mythical ingredients to secure this essence – water and, obviously, the mask (fig. 6). Y Thanks to his two Venetian sojourns (1786 and 1790), Goethe (fig. 7) formulated a double image of the city, an image which would set the pace for all ensuing literature, especially German literature. The infinitesimal lapse of time between his first and second stays actually opened up, for the poet and dignitary from a microscopic state within absolutist Germany, an indescribable abyss between a before, with its security and order within the world, and an after, with its uncertainty and disorder. Irritated more than frightened by the French revolution that, according to Thomas Mann, he himself had promoted with his Werther, Goethe places alogside his radiant Venice in Voyage to Italy a rain-soaked, filthy, corrupt and treacherous Venice in his Venetian Epigrams, displaying his usual authority in establishing the two fundamental coordinates of the relationship between great literature (and not only great German literature) and the city: attraction and repulsion. What has changed in considerations of Venice, and before the events that were to lead to the loss of independence, is the atmosphere: Venetians themselves, as the disenchanted, prophetic Goethe observed them in 1790, seemed to look on the end of their great history with numb indifference, aiding and abetting those who would attribute to the city its status as extraterritorial and extra-temporal, substantially and intimately extraneous to the vicissitudes not only of history, but of real life, as we said before. This sort of oneiric transfiguration, which anchors the city to the slimy seabed of an indistinctly defined past, a grandeur whose essential cipher is the fact that it belongs hopelessly to the past, constitutes the characterising element of the relationship between European literature and Venice: it is from this labyrinthine navigation through and against history that the myth of a decadent Venice, of the simulacrum and the dead city, is born. Y But the relationship between Austrian writers and poets and Venice is enriched and rendered more complex by another fact which, even though it does not directly impact on historical events, as we shall shortly see, nonetheless derives from historical events: the profound sense of an intimate affinity, a native, metahistorical 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 81 belonging. Throughout the 18th century, and right up to the French revolution, Venice was, for Austria, the happy face of a proximate alterity, where intense economic relations are also nourished by the atmosphere of liberty (and libertinage) of the city of carnivals and gambling. It is the other face (that of a mask, in other words) of the Venice of Goethe’s Epigrams: it is the city of hedonism, the city that gave birth to that Casanova who, not surprisingly, was transformed into a literary myth thanks to the Austrians Hofmannsthal and Schnitzler, and precisely when, wracked by competing nationalisms, the immense Austro-Hungarian empire began to fall to pieces. It therefore became almost de rigueur for authors to project the rumblings of an imminent “gay apocalypse” of the empire onto the city of Venice (fig. 8). Y Before then, just as had happened to the English, French and Germans, Austria’s Venice had simply been Venetian, and it made very little difference under whose thumb it happened to be. That the city Franz Grillparzer stayed in in 1819 was once again politically “Austrian” is an incidental fact, something the author didn’t consider important enough to even note in his diary. What he does note, however, is the emotion he felt when faced with what he defined “petrified books, poets 0020.saggi.qxd 81 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 82 from the 18th to the late 20th centuries: attractions and repulsion 0020.saggi.qxd 10. Gustave Moreau, Venezia, acquerello, 18801885, Parigi, Musée Gustave Moreau. 82 Gustave Moreau, Venice (watercolour), 1880-5, Paris, Musée Gustave Moreau. 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 83 history”: the sight of the Bridge of Sighs provoked a literary outburst on the contemptible, futile and bloody vagaries of human history, marked as it is by massacres and tyrannies that, apart from pain, leave no lasting trace. Not a word on the present, on how the city is governed, but, on the other hand, a colourful description of its beauty and how to appreciate it: “If there is anyone who, on seeing St Mark’s Square for the first time, doesn’t feel their heart skip a beat, then they should run off and dig a grave because they must, indubitably, be dead” (fig. 9). Y Friedrich Halm’s Das Haus an der Veronabrücke, however, was published in the early 1860s, and this novel by one of Grillparzer’s contemporaries and “rivals” offers a darker Venice, where a dramatic love story culminates in the suicide of the main character. Mannered, though not without a certain fascination, it offers us a portrait of 16th-century Venice according to stylemes that we would now define as noir and that hark back to Schiller’s prose work Der Geisterseher, a progenitor of a genre that would culminate in Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice. Here as well, what is most striking, considering Halm’s legitimising bent, is the complete lack of reference to Venice’s Austriazität, which is nonetheless also lacking in Ferdinand von Saar’s short novel Seligman Hirsch (1880), where the city is seen as a melancholic place of abandonment and solitude where the protagonist (a wealthy Jew whose addiction to gambling has led to his ruin) is banished by his children and where he eventually dies. Here Venice, far from being represented as “Austrian”, is actually seen as a land of exile, which is rather curious considering that Saar, who had served as an imperial officer in one of the mixed regiments recruited in the Veneto area, spoke fluent Italian and was profoundly familiar with Italy and Venice in particular (fig. 10). Y On a lighter and more frivolous note (but not for this any less laden with consequences in its construction, which is no longer political but decidedly nostalgic and sentimental, of an “Austrian” Venice), we should mention Johann Strauss’s operetta Eine Nacht in Venedig (1883), whose libretto by Friedrich Zell and Richard Génée is a modern re-interpretation of the 18th-century myth of the city of the carnival and the pleasures of life, spiced up with a tamed down exoticism that was just right for the middle classes: originally a literary icon, the city begins to be transformed into a tourist and honeymoon destination. It was in that atmosphere that, a few years later, in 1895, a great deal was ma- books, poets 0020.saggi.qxd 83 from the 18th to the late 20th centuries: attractions and repulsion 0020.saggi.qxd 84 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 84 de over the inauguration in Vienna of what seems to have been the first theme park in history. The park was called Venedig in Wien, and it was a faithful reconstruction of the streets, bridges, canals and historical façades of a “picturesque” Venice for the whole family. Now thirty years after the end of Austrian domination, the city (which most people felt had quite simply remained itself) had powerfully shot into the realm of great popular myths, and Vienna was where we were given our first taste of its 20th-century apotheosis: its trivialisation and reduction to cliché, the symbol par excellence of modern mass tourism. Melancholic and solitary visitor to Venice (the real Venice), the great Peter Altenberg describes, in one of his scathing Märchen des Lebens, that triumph of modern non-authenticity that seemed to have mesmerised his fellow countrymen (even though not for long, considering that it was dismantled only five years later). Nothing at all was missing in the fake Viennese version of Venice: there were “gondoliers, who dextrously manoeuvre down the canal with their chivalrous manners”, “thirty thousand people who walk up and down the squares and flock the bridges”, and couples wondering through the virtual city pretending to be transported by the emotion of a “night in Venice”... Y But at the same time, another Venice, not even vaguely touched upon by that process of gradual appropriation and trivialisation we’ve just mentioned, began to take shape in the pages of an Austrian author. Its creator describes it as “the most beautiful city in the world”, and communicates an entirely new and different impression: gone is the fear of entrapment and perdition, and gone is the cheap enthusiasm of a simplistic joie de vivre; what we have is the excitement and boundless surprise of a first discovery. In this sense, we could say that Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s Venice is truly the first and only “Austrian” Venice we have (fig. 11): without requiring any process of appropriation, Hofmannsthal simply recognises in the city a happy land of the heart, a locus of the heart and life that belongs to the city by virtue of a sort of ancestral birth right, regardless of any historical contingency. Not unlike that of many predecessors and contemporaries, the Venice visited by the young protagonist of the novel Andreas oder die Vereinigten (written between 1907 and 1913, left unfinished and published posthumously in 1930) is also nocturnal and perfidious, and he, too, encounters unnerving characters, their identity fickle and their intentions ambiguous. But his immersion in disor- 22-07-2009 11. Antonio Zona, Venezia afflitta tra le braccia della liberata Milano, 1861, Genova, Museo del Risorgimento. Antonio Zona, Venice Afflicted in the Arms of Liberated Milan, 1861, Genoa, Museo del Risorgimento. 11:27 Pagina 85 der does not take place under the dark sign of perdition (as for Mann’s contemporary Aschenbach), but under the happy sign of a path leading to light, maturity and recomposition. A recurring character in his work from 1892, the year of his Der Tod des Tizian, Venice is, for Hofmannsthal, the privileged site of adventures whose aftermath is the positing of an existential turning point, the crucial point where the characters’ soul experiences utmost concentration and they grasp the truth of their own destiny, the sense of their calling in the world. This can best be seen in his 1907 Der Dichter und diese Zeit, where the visual excitement of the city as it reveals itself in its crepuscular splendour changes into the revelation of creativity as immense, almost divine, power, whose imanent impiety can only be emended through an absolute devoution to human undertaking. Barely touched on in this work and thematised in the unforgettable Andreas, the site of this undertaking, this proferring of love that gifts the substance of life, is no longer Venice, the city of abysmal intuition, but the intermediary stage of the journey back to Vienna: the crystalline purity of the mountains and valleys of Carinthia, the limpid surface where a redeemed profundity can finally conceal itself. Y A completely different Venice, desolated and oppressed under a dark, sooty sky, dirty and shabby, is made to welcome Schnitzler’s Casanova (fig. 12). In the short novel entitled Casanova’s Homecoming, published just after the first world war, the writer projects onto the great Venetian figure (who had already been used as a protagonist in two early plays by his freind Hofmannsthal) the sense of anguish and loss at the blind, incessant churning of time and history (figs. 1, 13). Not too different in atmosphere, the Venice described in 1928 by Franz Werfel in his novel Verdi emends, to some extent, his dark and melancholic Stim- books, poets 0020.saggi.qxd 85 from the 18th to the late 20th centuries: attractions and repulsion 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 12. Marcello Mastroianni è stato un famoso Casanova nel film Il mondo nuovo di Ettore Scola, 1982. Marcello Mastroianni played Casanova in Ettore Scola’s The Night of Varennes, 1982. 86 11:27 Pagina 86 mung, turning it into the sign of the difficult path that would lead the Italian musician to recover his vocation in discovering “Venetian” music in the form of his Tristan by his arch rival Wagner. The Venice-music pairing, already adumbrated by the German Platen and thematised in a famous aphorism by Nietzsche (according to which he could find no other term for music if not Venice), is also the hidden cipher of Rainer Maria Rilke’s lagoon: the poet, who stayed in Venice on several occasions between 1897 and 1920, sees throughout the city a “symphony of colours” that underline its evanescence, its “non-being”; “... the city that always, where a flash / of sky breaks onto high tide, / without ever being, is formed” (“Venetian Morning”, 1908). Colours and sounds overlap and combine to form a unique sensation that, once again, harks back to a loss, a fall: “The city no longer floats like a bait / that captures each day as it appears; / like broken glass the palazzi echo / with your gaze. And, exhausted, killed / summer hangs like a marionette, / head down, in the gardens” (“Late Autumn in Venice”, 1908). Y An affinity that is virtually complete identification (no less intense that Hoffmansthal’s) is characteristic of the relationship between Theodor Däubler, an Austrian who grew up in Triest, and Venice. According to the poet himself (“... without Venice I would have been lost”), his Venetian experience was decisive during his adolescence and became a sort of personal myth, the happy site of completeness and erotic revelation: “The graver the evening, the more imposing the city. / It is as if Dionysus were hovering above us. / The lagoon at his feet, like a panther” (“The Northern Light”, 1921). Y But with the explosion of mass tourism and cultural consumerism in the second half of the 20th century, the myth of Ve- 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 87 books, poets 0020.saggi.qxd 13. August Friedrich Pecht, Dopo la resa di Venezia nell’anno 1849, 1854, Praga, Národní Galerie. August Friedrich Pecht, Following Venice’s Surrender in 1849, 1854, Prague, Národní Galerie. nice also began to lose its lustre and become self-referential, inexorably losing its appeal, character and originality. It is now difficult if not impossible to find witnesses to a living, authentic relationship with the city, and we are forced to courageously acknowledge the new state of things. And this is exactly what Gregor von Rezzori does in his bitter, provocative novel from 1986. In his Kurze Reise übern langen Weg, set in a Venice all but destroyed by hordes of tourists, a semi-cultured Austrian couple, are hellbent on “consuming” culture in a senseless litany of visits to city museums in an inane attempt to fill the desolate void of their life. Thus, with the writer that Claudio Magris defines as the last representative of the Habsburg myth, the city-symbol of a thousand-year-old civilised tradition is transformed, as if through a deforming mirror, into a caricature of itself: in the sad sign of the unforgettable inauthenticity of our times. 87 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 88 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 89 una predilezione che inizia forse nel 1533, con tiziano un acquisto dietro l’altro, nasce la più ricca e documentata raccolta veneziana all’estero Sylvia Ferino Pagden «An Bilder schleppt ihr hin und her Verlornes und Erworbnes; Und bei dem Senden kreuz und quer Was bleibt uns denn? – Verdorbnes!» Johann Wolfgang Goethe 1. Paolo Veronese, Giuditta con la testa di Oloferne, Vienna Kunsthistorisches Museum. Paolo Veronese, Judith with the Head of Holofernes, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. il racconto 0020.saggi.qxd «In fatto di quadri, trascinate qua e là roba perduta e roba acquisita; e a furia di spedire a destra e a sinistra, a noi cosa rimane? – Roba priva di valore!» Johann Wolfgang Goethe, Tutte le poesie, a cura di R. Fertonani, Milano 1989 Y Si resta ancora oggi sbalorditi se si pensa a quante famose raccolte d’arte vengono spostate in Europa intorno al 1650, in seguito a eventi spesso drammatici, per ricomporsi poi in luoghi e proprietà sempre nuovi. Basti pensare alla vendita Gonzaga nel 1627-1629, al saccheggio di Praga e al trasferimento di gran parte della collezione di Rodolfo ii a Stoccolma nel 1648, e intorno al 1650, alle vendite Commonwealth, ma soprattutto Buckingham e Hamilton, le cui collezioni costituiscono ancora oggi il nucleo del Kunsthistorisches Museum di Vienna. Già nel 1952, lo storico dell’arte e docente a Oxford Sir Ellis Waterhouse considerava la raccolta di dipinti del Kunsthistorisches come la meglio documentata al mondo. Questo non soltanto perché le liste di vendita, da lui pubblicate, delle collezioni di Bartolomeo della Nave (fig. 2), dei Priuli e di Nicolas Regnier (o Niccolò Renieri) permettono di rintracciare a Venezia, e in rari casi fino ai committenti stessi, le origini di gran parte delle opere del museo, ma anche perché gli stessi Asburgo – antesignani in questo – fecero realizzare documentazioni visive di grande originalità, come i Galeriebilder e il Theatrum Pictorum. Accanto alle opere di pittori veneziani, in queste collezioni figuravano anche quelle di autori appartenenti ad altre scuole, poiché a Venezia, durante il Seicento, si era sviluppato un mercato dell’arte assai importante. Il settore più famoso delle collezioni austriache rimane tuttavia quello della pittura veneziana: si pone dunque il problema se questo sia dovuto solamente al caso, o se invece la casa d’Austria avesse realmente una netta predilezione per i pittori veneti. 89 una predilezione che inizia forse nel 1533, con tiziano 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 2. Zorzi da Castelfranco detto Giorgione, Ritratto di donna (“Laura”), Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, già in collezione Bartolomeo della Nave nel 1638, nel 1650 circa in quella dell’arciduca Leopoldo Guglielmo. Giorgione, Portrait of a Young Woman (“Laura”), Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, originally in the Bartolomeo della Nave collection in 1638, and in that of the archduke Leopold Wilhelm in 1650 circa. 90 11:27 Pagina 90 Y La ricchezza delle raccolte che ancora oggi fanno parte del Kunsthistorisches Museum – dipinti ed oggetti d’arte, ma anche armature, antichità greco-romane ed egizie, la collezione numismatica, per non parlare dei famosi manoscritti, disegni e stampe, le raccolte storico-naturali e altro, che oggi si trovano alla Nationalbibliothek, all’Albertina e al Naturhistorisches Museum - è dovuta a poche personalità straordinariamente interessanti della casa austriaca degli Asburgo. A differenza di più recenti istituzioni, come la National Gallery di Londra o la Gemäldegalerie di Berlino, le cui principali acquisizioni risalgono al xix secolo, già ai primi dell’Ottocento la collezione imperiale aveva raggiunto l’aspetto definitivo e del tutto particolare di una raccolta privata principesca. Ancora oggi riflette le particolarità dei gusti degli Asburgo: anche se la pittura tedesca e fiamminga ne costituiscono la parte più consistente, la pittura italiana è considerevole per nomi e scuole. Il Trecento e Quattrocento italiani, che hanno conosciuto grande fortuna solo dal xix secolo in poi e costituiscono il fiore all’occhiello della National Gallery di Londra e di quella di Washington, del Metropolitan Museum di New York, della Gemäldegalerie di Berlino, al Kunsthistorisches Museum sono invece quasi assenti. Anche per questo, la raccolta dei dipinti italiani degli Asburgo, a parte qualche eccezione, inizia proprio con i pittori del xvi secolo. La carenza di opere francesi, inglesi e il numero ridotto di quelle olandesi, riflette inoltre, in modo evidente e oggi ormai irreparabile, i legami politici della dinastia. Y Il prevalere dei ritratti sulle tematiche narrative, mitologiche, religiose o allegoriche, in tutte le scuole, si spiega con le esigenze dinastiche della famiglia, e quindi dei rapporti con i casati con essa imparentati. Già Ferdinando ii, duca del Tirolo dal 1529 al 1595, mette insieme una straordinaria collezione iconografica, composta da oltre mille ritratti in formato cartolina delle personalità di spicco non solo delle case regnanti d’Europa, ma anche di papi, di sultani, di personaggi celebri in campo letterario, scientifico ed altro. Anche se i dogi sono ben pochi, vi figurano invece alcuni esponenti della famiglia Soranzo. La Portraitgalerie di Ambras, istituita nel 1976, riunisce ritratti di personaggi famosi della Venezia del Cinquecento, i dogi Francesco Donato, Girolamo Priuli, Niccola da Ponte e il famoso committente di Palladio Marcantonio Barbaro, eseguiti da artisti più o meno noti. Un gruppo di altri ritratti maschili veneziani del Cinquecento di qualità più o meno alta – personaggi e autori tuttora non identificati 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 91 e quindi al cui interno sono forse ancora possibili alcune scoperte – si trovano nella Sekundärgalerie del Kunsthistorisches Museum, istituita nel 1969 da Frederike Klauner e Günther Heintz. Y Sembra però che la predilezione degli Asburgo per la pittura veneziana sia iniziata proprio nel 1533, quando l’imperatore Carlo v conferisce a Tiziano l’ordine dello Speron d’oro, per i vari ritratti da lui eseguiti a Mantova e Bologna. Richiamandosi in un documento al rapporto di Alessandro Magno con Apelle, unico artista ammesso a ritrarre il sovrano, Carlo elegge Tiziano a suo pittore prediletto. Da questo momento, Tiziano è l’artista preferito della casa asburgica (fig. 3): dell’imperatore e di conseguenza dell’entourage della sua corte. Ma anche dei suoi parenti, della sorella Margherita d’Ungheria, e di suo figlio Filippo, poi re di Spagna, per il quale Tiziano crea, oltre a molte altre opere, le sue “poesie” più coinvolgenti. Non sembra che, nello zelo di servire gli Asburgo, Tiziano avesse in mente di indirizzare verso la pittura veneziana il loro gusto per i secoli a venire, anche se in entrambi i rami del casato, quello spagnolo e quello austriaco, proprio questo pare essere accaduto. Y Tenendo conto del fatto che nel Cinquecento la casa d’Austria disponeva di mezzi finanziari assai più ridotti di quella spagnola, è probabile che l’incarico a Tiziano di dipingere ben 15 ritratti della famiglia di Ferdinando i, fratello minore di Carlo v, dei quali si parla in un documento, non sia mai stato portato a compimento. Compiti ritrattistici di questo tipo li svolgeva, per Ferdinando, il suo pittore di corte, Jacob Seisenegger, che non poteva certo eguagliare la qualità, la fama e i prezzi dell’artista preferito dal fratello. Ciononostante, viene attribuita a Seisenegger l’in- il racconto 0020.saggi.qxd 91 una predilezione che inizia forse nel 1533, con tiziano 0020.saggi.qxd 92 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 92 tuizione del Ritratto di Carlo V con il suo cane, idea che, secondo alcuni, Tiziano avrebbe copiato nel proprio dipinto, oggi al Prado. Ma le radiografie del dipinto spagnolo mostrano diversi cambiamenti nella stesura della composizione, indizio inequivocabile di originalità. Ironicamente, entrambi gli artisti per anni, se non decenni, hanno lottato presso le corti asburgiche per riscuotere il pagamento loro dovuto. Y I problemi finanziari, o meglio i prezzi raggiunti dalle opere di Tiziano, sembrano aver anche condizionato, e infine ridimensionato, il forte interesse di Massimiliano ii, figlio di Ferdinando i. Il breve periodo di pace nelle guerre contro i Turchi permette d’iniziare la costruzione di una residenza fuori porta, con giardini zoologici e botanici, e di godere del talento di Giuseppe Arcimboldo e di altri artisti. E spinge inoltre Massimiliano a cercare di acquistare opere di Tiziano. A novembre 1568, si sviluppa una corrispondenza con Veit von Dornberg, ambasciatore imperiale presso la Repubblica veneziana, che propone all’imperatore l’acquisto di alcune “poesie“ di Tiziano, quali «la fabula de Calisto, scoperta graveda alla fonte, la fabula de Ateone a la fonte, la fabula de’ isteso, tramutato in cervo et lacerato dai suoi cani, la fabula de Adone andato alla caza contra il volere di Venere fu dal cinghiale ucciso, la fabula de Andromeda, ligada al sasso et liberata da Perseo, la fabula de Europa portata da Jove converso in tauro. Et tutti detti quadri sono a buonissimo termine et sono un palmo più largi che 22-07-2009 3. Tiziano Vecellio, Cristo e l’adultera, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. Titian, Christ and the Adulteress, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. 11:27 Pagina 93 quello della religion, che già si mandò a sua maestà cesarea per essere quelli più pieni di figure rispeto alle fabule». Y Il 25 febbraio 1569, Veit von Dornberg riceve l’incarico di pagare 100 corone a Tiziano per un dipinto che, anche se non è descritto, si potrebbe identificare con Diana e Callisto, ancora oggi conservato al Kunsthistorisches Museum. Inconsueto che questo quadro venga raffigurato in grandi dimensioni nel Galeriebild che Leopold Wilhelm spedisce in Spagna nel 1653 da Bruxelles, e anche nel Theatrum Pictorum di Teniers, che riproduce a stampa i dipinti italiani più importanti, ma non nell’inventario del 1659, compilato a Vienna. Si potrebbe dunque concludere che egli abbia incluso questo quadro per imporsi alla linea spagnola, che si vantava di essere proprietaria di numerose opere di Tiziano, anche se in realtà non era di sua proprietà bensì della famiglia? Del dipinto con la «religion» di cui parla von Dornberg si è invece perduta ogni traccia. Y Anche se il fratello minore di Massimiliano ii, l’arciduca del Tirolo Ferdinando è il primo collezionista veramente importante della casa d’Asburgo, noto per la sua Wunderkammer e per la raccolta di armature appartenute agli eroi (l’armamentarium heroicum, di cui fu pubblicato il primo catalogo illustrato in assoluto, si veda p. 47), egli, probabilmente anche a causa delle sue ridotte possibilità finanziarie, non si interessava né ai dipinti dei grandi pittori del passato né ai contemporanei. Suo zio, l’imperatore Rodolfo ii, il più importante mecenate e collezionista tra gli Asburgo, è invece un grande amante della pittura. Le sue lunghe trattative con la Spagna, svolte dall’ambasciatore Hans Khevenhüller per acquistare gli Amori di Giove di Correggio e Amore che forgia l’arco di Parmigianino, sono ormai leggendarie. Raccoglie opere di Dürer e dei suoi seguaci; commissiona dipinti a Bartolomeus Spranger, Joseph Heintz, Hans von Achen e ad altri contemporanei. Von Achen si trovava a Venezia nel 1603 in veste di agente per Rodolfo ii, ma non sappiamo quali opere egli potrebbe aver trattato per l’imperatore. Ridolfi ci informa che Jacopo Bassano avrebbe inviato a Praga una serie con i dodici mesi, di cui scrive Francesca del Torre in questo stesso «VeneziAltrove». Fra i molti doni che Rodolfo riceveva come imperatore spicca, oltre all’Autoritratto allo specchio convesso di Parmigianino da parte di Alessandro Vittoria, la Danae di Tiziano inviata da Roma nel 1600 all’imperatore dal cardinale Montalto. A questo proposito, che nei Galeriebilder di Leopoldo Guglielmo compaia una Danae tizianesca crea un po’ di confusione: anche se la vecchia vie- il racconto 0020.saggi.qxd 93 una predilezione che inizia forse nel 1533, con tiziano 0020.saggi.qxd 94 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 94 ne rappresentata decisamente di profilo e Danae guarda in alto, verso sinistra. D’altronde ben più di una Danae era elencata negli inventari antichi. Y Ma il vero protagonista del collezionismo di dipinti veneziani è il famoso arciduca Leopoldo Guglielmo, figlio dell’imperatore Ferdinando ii, il quale, a coronamento di una complessa carriera ecclesiastica e politico-militare è Governatore dei Paesi Bassi dal 1647 al 1656. Luogo e periodo si mostrano di singolare fortuna per la sua passione collezionistica. Questa si sarebbe manifestata già prima della sua partenza, in quanto aveva inviato agenti in cerca di opere importanti oltre che a Roma, Napoli, Madrid e altri luoghi anche a Venezia; e secondo Carlo Ridolfi possedeva già una Madonna di Bellini («Il Signor Arciduca Leopoldo vivente, il quale con la sua Regia munificenza acresce gratie continue alla Pittura, possiede del Bellino una divina imagine della Vergine»). Giunto a Bruxelles si mette subito a caccia di capolavori di artisti fiamminghi e olandesi, dei quali vuole acquistare due dipinti: uno per il fratello imperatore, Ferdinando iii, e l’altro per la propria collezione. Y Quando, fra il 1649 e 1650-1651, a causa della guerra civile in Inghilterra, le collezioni inglesi Buckingham e Hamilton giungono nei Paesi Bassi per essere vendute ad Amsterdam e ad Anversa, l’arciduca vi riconosce, a ragione, un’occasione unica, da non perdere. Mentre acquista singoli dipinti dalla vendita Buckingham, per lo più destinati alla collezione del fratello per compensare le perdite sofferte da Praga in seguito al saccheggio degli Svedesi del 1648, riserva la collezione Hamilton al proprio personale godimento. La pittura veneta primeggiava in entrambe le raccolte. Gran parte di questi dipinti costituisce ancora oggi la spina dorsale della collezione del Kunsthistorisches Museum. Fra le opere venete più importanti provenienti dalla vendita Buckingham e destinate alla corte imperiale di Praga, spiccano l’Ecce Homo di Tiziano, L’unzione di David di Veronese, le tavole con scene dall’Antico Testamento di Tintoretto e Ercole e Onfale di Bassano. Sappiamo oggi che alcune opere nella collezione dell’arciduca provengono dalla collezione di Carlo i, re d’Inghilterra: ad esempio la Lucrezia, la Ragazza con pelliccia e forse anche Isabella d’Este di Tiziano, insieme a opere di altri artisti italiani, fra i quali Parmigianino, Dosso, Caravaggio, Fetti e altri. Sembra però che l’arciduca, non potendo partecipare direttamente – in segno di rispetto per una casa regnante caduta in disgrazia – al “Commonwealth Sale”, abbia acquistato le opere che gli venivano offerte da vari mercanti e intermediari. 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 95 Y Infinitamente più ricca di pittura veneziana è la vendita Hamilton, che riunisce le collezioni di Bartolomeo della Nave, Priuli e Regnier. È più facile elencare qui i quadri famosi di artisti di altre scuole, come la Santa Margherita di Raffaello della collezione Priuli, o opere di Guido Reni, Domenico Fetti e Valentin de Boulogne, piuttosto che i pezzi più forti dei veneziani: troppe sono le opere di Bellini (figg. 4, 5), Giorgione, Tiziano, Tintoretto (fig. 6), Veronese, Palma (fig. 7), Bordone, Pordenone, Lotto, ma anche Savoldo e tanti altri. Siamo in attesa della pubblicazione di ulteriori liste di vendita di Bartolomeo della Nave, alcune delle quali preannunciate anche in altri numeri di «VeneziAltrove», che promettono ulteriori informazioni a completamento di quelle già pubblicate da Waterhouse. Tra gli inventari e le liste della collezione Hamilton pubblicati da Klara Garas, si è mostrato particolarmente interessante l’elenco del 1649, compilato in francese, dal quale risulta chiaro che molte opere di altri artisti furono attribuite a Tiziano e a Giorgione per rendere la collezione ancora più attraente, specialmente per un Asburgo. È però lo stesso arciduca Leopoldo Guglielmo a fornire la documentazione visiva più efficace di tutte. Per soddisfare il suo orgoglio collezionistico, si fa ritrarre più volte nella sua “galleria” con il suo entourage dal pittore di corte David Teniers il giovane (fig. 8). In ognuno di questi dipinti, i famosi Galeriebilder che egli poi regalava a diverse personalità, fa riprodurre una scelta di opere mirata a stupire i destinatari: per la corte viennese, e in particolare per il fratello Ferdinando iii sposato con una Gonzaga, si fa ritrarre con la vasta collezione di pittura italiana; per il cugino spagnolo, il re Filippo iv di Spagna, fa spiccare provocatoriamente le “poesie” di Tiziano, includendo possibilmente anche opere già acquisite dai suoi predecessori, come Diana e Callisto. Sono invece in minoranza i Galeriebilder che si concentrano sulla pittura nordica. Y Altro strumento di pubblicizzazione è il Theatrum Pictorum del 1660, anch’esso focalizzato sulla pittura italiana, e soprattutto veneziana, eseguito da David Teniers in condizioni non proprio facili, a causa della partenza improvvisa dell’arciduca da Bruxelles nel 1656 con parte della collezione. Oltre alla complessa procedura di far realizzare le incisioni da artisti vari (fra cui Lucas Vostermann, Nikolaus van Hoy, Jan van Troyen, Peter Lisebetten) sulla base di copie dipinte in piccolo formato da Teniers stesso, questa raccolta di incisioni ha ancor oggi un colossale valore documentario, anche perché ci aiuta a identificare opere che in se- il racconto 0020.saggi.qxd 95 una predilezione che inizia forse nel 1533, con tiziano 0020.saggi.qxd 96 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 96 coli successivi sono state regalate, rimosse e rubate alla collezione imperiale. E in più, ci offre uno sguardo nel nuovo allestimento della Stallburg. Dal punto di vista estetico non si può che concordare con il famoso medico e collezionista Charles Patin, che già nel 1673 criticava fortemente la qualitá di esecuzione delle stampe, considerandole «copie che deformano gli originali e alterano quanto c’è di più bello al mondo: non vi si vedono che gli errori dell’esecutore, e nulla dell’eccellenza di queste grandi idee». Lo strumento non visivo, ma più importante di tutti, è costituito dall’inventario della collezione dell’arciduca, datato 1659, che costituisce tutt’oggi un elemento preziosissimo per la valutazione della storia attribuzionistica. In alcuni casi, esso si differenzia infatti in modo straordinariamente interessante dalle liste di Bartolomeo della Nave, dagli Inventari Hamilton e il Theatrum Pictorium che lo precedono di poco più che un ventennio. Attraverso questi strumenti è, ad esempio, possibile ricostruire la presenza di un capolavoro come la Giuditta di Veronese (fig. 1), documentata da Teniers (fig. 10), e incisa negli inventari successivi (figg. 9, 11). Oltre a circa 517 dipinti italiani, il Theatrum ne comprende 800 tra olandesi e tedeschi; 542 tra sculture, bronzetti e altri oggetti, e 343 disegni. Altri complessi collezionistici, come la sua famosa raccolta di arazzi e quella di oggetti di culto, fanno comprendere come il principio che guidava l’arciduca fosse ancora universale, anche se non più enciclopedico. Opere italiane entrano nelle collezioni asburgiche anche attraverso la linea tirolese, cioè l’arciduca Ferdinando Carlo, sposato con Anna de’ Medici: non solo la famosissima Madonna del Prato di Raffaello e il Battesimo di Cristo del Perugino, ma anche il Ragazzo con la freccia di Giorgione, che Michiel aveva visto nel 1531 «in casa de M. Zuan Ram». Y Sembra proprio che, nel secolo successivo, Carlo vi e Maria Teresa abbiano indirettamente contribuito alla perdita permanente di opere veneziane. Nel 1732, infatti, l’imperatore inviava a Praga un gruppo considerevole di dipinti – per di più della collezione di Leopoldo Guglielmo – fra i quali spiccano la Resurrezione di Lazzaro del Pordenone e l’Adultera di Tintoretto, tuttora a Praga. Le opere di Giorgione o a lui attribuite nella lista di vendita di Bartolomeo della Nave, fra cui La nascita di Paride, Tarquinio e Lucrezia ed altre, sembrano essere state vittime della necessità di arredare le residenze di Pressburg e Budapest. Altre ancora, come il Cristo deriso di Tiziano, finivano nella collezione Bruckenthal a Hermannstadt (Sibiu). 22-07-2009 4. Giovanni Bellini, Presentazione al tempio, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. Giovanni Bellini, Presentation at the Temple, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. 11:27 Pagina 97 Y A fine Settecento è concluso il famoso scambio tra i fratelli Asburgo. L’imperatore Francesco e Ferdinando iii granduca di Toscana si lasciano ispirare da nuovi criteri “scientifici” per la riorganizzazione delle raccolte asburgiche e medicee; lo scopo principale era quindi di dare una visione più equilibrata dal punto di vista storico e delle scuole. Anche se i dipinti giunti da Firenze, fra cui spiccano la Sacra Famiglia del Bronzino, il Ritorno di Agar di Pietro da Cortona, il Lamento del Cigoli, l’Astrea di Salvator Rosa, Cristo con Maria e Marta di Alessandro Allori, costituiscono un importante arricchimento, va purtroppo segnalata la perdita dell’Allegoria sacra di Giovanni Bellini, della Flora e della Madonna delle rose di Tiziano, del cosiddetto Gattamelata, di Adamo ed Eva e dell’Adorazione di Albrecht Dürer, e dobbiamo ritenerci fortunati se la Ninfa con pastore di Tiziano, l’opera tarda più importante del maestro nella collezione viennese, fu allora rifiutata da Firenze. Anche all’era di Napoleone si devono perdite di opere venete, alcune delle quali si trovano ancora in Francia, come le due tele di Bassano oggi a Digione. Y Relativamente poco gloriosa sembra poi la storia ottocentesca dei trasferimenti da Venezia alla corte di Vienna, uno nel 1816 di 14 opere venete provenienti dai depositi dell’Accademia di Belle Arti e dal deposito della Commenda di Malta, e nel 1838 un altro nucleo più consistente di ben 50 dipinti ripartiti in 18 casse, con dipinti provenienti dalle chiese e dai conventi soppressi nel periodo napoleonico. Inoltre, sotto la direzione del principe di Metternich, viene scelto e trasferito un nucleo di opere destinato all’Accademia delle Belle Arti di Vienna. Come se non bastasse, il governo austriaco predispone anche la spedizione di un gruppo di opere venete nella Bucovina, per decorare le chiese di quella poverissima regione. Poco chiara risulta poi la vicenda, a questa connessa, della parziale restituzione nel 1866, che costituisce un ca- il racconto 0020.saggi.qxd 97 una predilezione che inizia forse nel 1533, con tiziano 0020.saggi.qxd 98 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 98 pitolo nero sia da parte degli Asburgo, sia da parte italiana, in particolare per gli sgradevoli strascichi databili al 1919, nel primissimo dopoguerra. Anche se non erano dipinti di ottima qualità, riconosciamo ancora, nelle vecchie immagini delle sale del Kunsthistorisches Museum, opere che oggi si ammirano nella Quadreria delle Gallerie dell’Accademia a Venezia, nel corridoio palladiano. Molto più piacevole per il Museo, oramai statale, è stata invece la possibilità di acquistare, nel periodo fra le due guerre mondiali, opere importantissime del Settecento veneziano, fra cui due delle famose pitture di Tiepolo di Ca’ Dolfin, o il Miracolo di un santo domenicano di Francesco Guardi, di cui il museo possedeva, tra l’altro, La festa della Sensa in piazza San Marco (fig. 12). Y Di una specifica valutazione dell’importanza della pittura veneta, espressa attraverso il suo allestimento e la sua posizione all’interno della raccolta asburgica, si può parlare solo a partire dal 1780 circa, quando Christian Von Mechel è chiamato a illustrare il suo progetto storico-artistico nella nuova presentazione della collezione imperiale di dipinti al Palazzo del Belvedere, costruito dal principe Eugenio di Savoia, e poi acquistato da Maria Teresa. Von Mechel aveva appena riorganizzato il Museo di Düsseldorf secondo i nuovi canoni storico-artistici, presentando le opere secondo criteri cronologici e ordinati per scuole artistiche. Egli faceva infatti iniziare il percorso con due sale dedicate alla pittura veneziana. E uno dei miei primi compiti di curatore della pittura italiana del Kunsthistorisches Museum è stato anche di risistemare le collezioni negli ambienti nuovamente restaurati. Quantunque nel precedente allestimento si iniziasse con Raffaello e il Rinascimento fiorentino, cioè fra’ Bartolomeo e Andrea del Sarto e i capolavori della pittura emiliana di Correggio e Parmigianino, mi è sembrato giusto, quasi doveroso sottolineare le preferenze e gli interessi più forti del collezionismo asburgico, cioè la pittura veneziana. Ho perciò cercato di concentrare in tre grandi sale i “pilastri” della pittura veneta del Cinquecento, cioè Tiziano, Veronese e Tintoretto, includendo Palma Vecchio e Giovane, Paris Bordone e dei Bassano, e lasciando le opere meno monumentali di Antonello da Messina, Bellini, Giorgione e Lorenzo Lotto per le gallerie laterali, che affiancano le grandi sale. Nonostante siano trascorsi ormai vent’anni, questa sistemazione, già in embrione nell’allestimento del primo dopoguerra, mi sembra tuttora valida e coerente: specchio rivelatore non soltanto del gusto, ma anche della storia collezionistica della casa degli Asburgo. 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 99 a predilection that perhaps began in 1533, with titian one purchase after another leads to richest and most documented venetian collection abroad the tale 0020.saggi.qxd Sylvia Ferino Pagden An Bilder schleppt ihr hin und her Verlornes und Erworbnes; Und bei dem Senden kreuz und quer Was bleibt uns denn? – Verdorbnes! Johann Wolfgang Goethe Y We are still now amazed if we think of how many famous art collections were moved around in Europe around 1650, following often dramatic events, to then come together again in new places and with new owners. Take, for example, the Gonzaga sale in 1627-29, the sacking of Prague and the transferring of a large part of Rudolf ii’s collection to Stockholm in 1648, and, in about 1650, the sale of “Common Wealth”, but above all of Buckingham and Hamilton, whose collections still now constitute the nucleus of the Kunsthistorisches Museum. In 1952, the famous art historian and Oxford don Sir Ellis Waterhouse thought the collection of paintings at the Kunsthistorisches was one of the best documented in the world. This was not only because the sales lists, which he himself published, for the collections of Bartolomeo della Nave (fig. 2), the Priulis, and Nicolas Regnier (or Niccolò Renieri) allow us to trace back to Venice, and in some rare cases the commissioners themselves, the origins of most of the works in the museum, but also because the Habsburgs themselves, who were precursors in this, had very original visual documentation created, such as the Galeriebilder and Theatrum Pictorum. Alongside works by Venetian painters, these collections also contained works by authors belonging to other schools as a rather important art market had developed in Venice in the 17th century. The most famous sector for Austrian collections is still nonetheless that of Venetian painting: the problem is therefore posed as to whether this is purely an accidental phenomenon, or rather if the Habsburgs really did have a preference for Veneto painters. Y The wealth of the collections that are still part of the Kunsthis- 99 a predilection that perhaps begins in 1533, with titian 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 5. Giovanni Bellini, Donna che si specchia, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum; da Venezia, nel 1638 passa nella collezione Hamilton, da dove l’arciduca Leopoldo Guglielmo l’acquista prima del 1659. Giovanni Bellini, Nude Woman in Front of Mirror, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. From Venice, the painting went to the Hamilton collection in 1638, whence Leopold Wilhelm bought it before 1659. 100 11:27 Pagina 100 torisches Museum (paintings and objets d’art, but also armour, Graeco-Roman and Egyptian antiquities, and the numismatic collection, but also the famous manuscripts, drawings and prints, historical-natural collections and more, which are now at the Nationalbibliothek, the Albertina and the Naturhistorisches Museum) is due to a few extraordinarily interesting individuals from the Austrian house of the Habsburgs. Unlike more recent institutions such as London’s National Gallery or Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie, whose main purchases date from the 19th century, the imperial collection had attained its definitive, and rather particular, form as a princely private collection as early as the 19th century. It still reflects the peculiar tastes of the Habsburgs: even if German and Flemish painting formed the largest part, Italian painting is also extremely important if we consider the names and schools. The Italian Trecento and Quattrocento, which became vastly popular only from the 19th century on and occupy pride of place at London’s National Gallery, Washington’s National Gallery, New York’s Metropolitan Museum and Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie, barely register at the Kunsthistorisches Museum. It is also for this reason that the Habsburgs’ collection of Italian paintings, apart from a few exceptions, begins with the 16th century painters. The dearth of French and English works, and the small number of Dutch works, also reflects the political bonds of the dynasty. Y The prevalence of portraits as opposed to narrative, mythological, religious or allegorical themes can be explained because of the dynastic demands of the family, and therefore the relationship with other, related houses. Ferdinand ii, Duke of Tyrol from 1529 to 1595, had already put together an extraordinary iconographic collection consisting of more than 1,000 portraits in card format of the most important figures not only of the reigning houses of Europe but also of popes, sultans, and famous personalities in the literary, scientific and other fields. Even though there are few doges, there are nonetheless quite a few exponents of the Soranzo family. The Ambras “Portraitgalerie”, founded in 1976, brings together portraits of famous characters from 16th-century Venice, the doges Francesco Donato, Girolamo Priuli and Niccola da Ponte as well as the famous patron of Palladio, Marcantonio Barbaro, undertaken by more or less famous artists. Another group of more or less high-quality portraits of 16th-century Venetian males (and where the individuals and authors have yet to be determined, which may lead to some interesting surprises) can be found at the 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 101 Sekundärgalerie of the Kunsthistorisches, founded in 1969 by Frederike Klauner and Günther Heintz. Y It would seem, though, that the Habsburgs’ predilection for Venetian painting began in 1533, when the emperor Charles v conferred on Titian the Order of the Golden Spur for the portraits he had undertaken of the emperor himself in Mantua and Bologna. In an official document, Charles v draws a parallel between himself and Alexander the Great’s relationship with Apelles, the only artist allowed to portray the sovereign, and chose Titian as his preferred painter. From then on, Titian was the Habsburgs’ favourite painter (fig. 3) – for the emperor, and therefore the whole courtly entourage, which also included his relativessuch as his sister Margaret of Hungary, and his son Philip, later king of Spain, for whom Titian created his most engrossing “poems” as well as many other works. It would not seem that, in his enthusiasm for the Habsburgs, Titian intended to channel their tastes towards Venetian painting for centuries to come, even though it must be said that in both branches of the family, the Spanish and the Austrian, this seems to be exactly what happened. Y Bearing in mind the fact that, in the 16th century, the Austrian branch had far less money than the Spanish branch, it is likely that Titian’s appointment to paint 15 portraits of the family of Ferdinand i, Charles v’s little brother, as are mentioned in an official document, was never confirmed. Portraiture of this sort was undertaken, for Ferdinand, by his court painter Jacob Seisenegger, who could obviously not compete with the quality, fame and prices of his brother’s favourite artist. Despite this, it is to Seisenegger that the original idea for Portrait of Emperor Charles V with a Dog is attributed – according to many, Titian copied the painting currently at the Prado. x-rays of the Spanish painting, how- the tale 0020.saggi.qxd 101 a predilection that perhaps begins in 1533, with titian 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 6. Jacopo Tintoretto, Ritratto di guerriero trentenne in corazza, Vienna Kunsthistorisches Museum. Jacopo Tintoretto, Portrait of a Soldier in Armour, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. 102 11:27 Pagina 102 ever, show several changes to the composition, unequivocal proof of originality. Ironically, both artists spent years, if not decades, demanding payment owed them from the Habsburg courts. Y Economic problems, or rather the prices being demanded for Titian’s work, seem to have conditioned, and finally cooled, interest on behalf of Maximilian ii, son of Ferdinand i. The brief period of peace in the wars against the Turks allowed the court to begin building a country residence, with zoological and botanical gardens and calling upon the talents of Arcimboldo and other artists. This also allowed Maximilian to try and acquire works by Titian. In November, 1568, there was a series of letters with Veit von Dornberg, imperial ambassador to the Venetian Republic, who suggested the emperor buy some of Titian’s “poems”, including “the tale of Callisto, discovered pregnant at the font, the tale of Actaeon and the font, the tale of the same changed into a hart and torn asunder by his dogs, the tale of Adonis gone hunting against Venus’ will and killed by the wild boar, the tale of Andromeda, tied to a rock and freed by Perseus, the tale of Europe spirited away by Jove on the back of a bull. And all these paintings are in good shape and are a span larger than those on religious themes, which are already being sent to Your Caesarean Majesty as they have many more figures compared to the tales”. Y On February 25, 1569, Veit von Dornberg was asked to pay Titian 100 crowns for a painting that, even though it isn’t described, was probably Diana and Callisto, which is still at the Kunsthistorisches Museum. It was unusual that this painting should be given in large format in the Galeriebild that Leopold Wilhelm sent to Spain in 1653 from Brussels, and also in Teniers’ Theatrum Pictorum, which is a print reproduction of the most important Italian paintings, but not in the 1659 inventory put together 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 103 in Vienna. Might we therefore conclude that he included this painting to impose on the Spanish line, who boasted that they were the owners of several works by Titian, even though it was not his but his family’s? All trace has been lost, though, of the painting on “Religion” mentioned by Dornberg. Y Even if Maximilian ii’s younger brother, the archduke Ferdinand of Tyrol, was the first truly important Habsburg collector, famous for his Wunderkammer and collection of armoury belonging to heroes (the so-called armamentarium heroicum, for which the very first illustrated catalogue ever was printed), he was not interested in the works by great maestros of the past or present, probably because of his limited funds. On the contrary, though, his uncle the emperor Rudolf ii, the most important of the Habsburg patrons and collectors, was a great admirer of painting. His protracted negotiations with Spain, undertaken by the ambassador Hans Khevenhüller for the purchse of Correggio’s The Loves of Jupiter and Parmigianino’s Cupid are legendary. He collected works by Dürer and his disciples; he commissioned paintings from Bartolomeus Spranger, Joseph Heintz, Hans von Achen and other contemporaries. Hans von Achen was in Venice in 1603 as an agent for Rudolf ii, but we don’t know which works he dealt with for the emperor. According to Ridolfi, Jacopo Bassano reportedly sent to Prague a series with the 12 months, about which Francesca del Torre writes in the present volume. Amongst the many gifts that Rudolf received as emperor, pride of place, along with Parmigianino’s Self-portrait in a Convex Mirror received from Alessandro Vittoria, goes to Titian’s Danae, sent from Rome by Cardinal Montalto in 1600. That Leopold Wilhelm’s Galeriebilder contains a Danae by Titian might create some confusion, even though the old woman is decidedly depicted in profile and Danae is looking upward, to the left. What’s more, there is more than one Danae listed in the old inventories. Y But the most important collector of Venetian painting is the famous archduke Leopold Wilhelm, the son of the emperor Ferdinand ii, who, at the apex of a complex ecclesiastical and political-military career, was Governor of the Lowlands from 1647 to 1656. The time and place of his governorship proved particularly providential for his bent for collecting. He had already shown interest before this, when he sent agents to scout for important works in Rome, Naples, Madrid and other places, including Venice. According to Carlo Ridolfi, in fact, he already had a Bellini Madonna (“The Lord Archduke Leopold living, who in his Regal the tale 0020.saggi.qxd 103 a predilection that perhaps begins in 1533, with titian 0020.saggi.qxd 104 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 104 munificence bestows grace on Painting, possesses a Bellini his divine image of the Virgin”). On arriving in Brussels, he soon sets off after masterpieces by Flemish and Dutch artists, by whom he wants to buy two paintings – one for his emperor brother, Ferdinand iii, and the other for his own collection. Y When, between 1649 and 1650-51, because of the civil war in England, the English Buckingham and Hamilton collections arrive in the Netherlands to be sold in Amsterdam and Antwerp, the archduke realised this was a once-in-a-lifetime chance. While he bought individual paintings from the Buckingham sale (mainly for his brother’s collection, to replace works lost in Prague following the Swedish sack of 1648), the Hamilton collection was for his own, personal pleasure. Veneto painting was the backbone of both collections. Many of these paintings still now are the cornerstone of the Kunsthistorisches Museum collection. Among the most important Veneto works from the Buckingham sale destined for the Prague court there are Titian’s Ecce Homo, Veronese’s Anointing of David, Tintoretto’s tables with scenes from the Old Testament, and Bassano’s Hercules and Omphale. We now know that some of the works in the archduke’s collection come from the collection of Charles i of England, such as, for example, Titian’s Lucrezia, Woman with Fur and perhaps even Isabella d’Este, along with works by other Italian artists, including Parmigianino, Dosso, Caravaggio, Fetti, and others. It seems, however, that the archduke, not being able to participate directly (as a sign of respect for a reigning house that had fallen) in the “Commonwealth Sale”, bought the works that various merchants and intermediaries offered him. Y Much richer in Venetian works was the Hamilton collection, which boasted works by Bartolomeo della Nave, Priuli and Regnier. It is easier to list the famous works by artists from other schools, such as Raffaello’s St Margaret from the Priuli collection, or works by Guido Reni, Domenico Fetti and Valentin de Boulogne, rather than the much greater prices of the Venetians: there are far too many works by Bellini (figs. 4, 5), Giorgione, Titian, Tintoretto (fig. 6), Veronese, Palma (fig. 7), Pordenone, Lotto, and even Savoldo and many others. We are awaiting other sales lists for Bartolomeo della Nave, some of which have even been given advance announcement in VeneziAltrove, which promise further information that would round out what Waterhouse has already stated. Among the Hamilton inventories and sales lists published by Klara Garas there is a very interesting 1649 list, com- 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 105 the tale 0020.saggi.qxd 7. Jacopo Palma il Vecchio, Sacra conversazione, Vienna Kunsthistorisches Museum. Il dipinto è rintracciabile (il secondo da destra nella terza fila dall’alto) nel quadro di Teniers a fig. 8. Jacopo Palma the Elder, Sacred Conversation, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. The painting can be seen (second from the right, third row from top) in Teniers’ painting in fig. 8. 105 a predilection that perhaps begins in 1533, with titian 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 8. David Teniers il giovane, La galleria dell’arciduca Leopoldo Guglielmo, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. David Teniers the Younger, The Archduke Leopold Wilhelm in the Gallery, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. 9. Ferdinand Storffer, Neu eingerichtetes Inventarium der Bilder der Kaiserlichen Bilder Gallerie in der Stallburg, tavola 43, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. Ferdinand Storffer, Neu eingerichtetes Inventarium der Bilder der Kaiserlichen Bilder Gallerie in der Stallburg, table 43, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. 106 11:27 Pagina 106 piled in French, from which it is clear that many works by other artists were attributed to Titian and Giorgione to make the collection even more appealing, especially for a Habsburg. But it is the archduke Leopold Wilhelm who provides us with the most effective visual documentation. To satisfy his pride as collector, he has himself portrayed on more than one occasion in his “gallery” with his entourage by the court painter David Teniers the Younger (fig. 8). In each of these paintings (the famous Galeriebilder that he would then give to different people) he made sure there was a choice of works that would surprise those for whom the Galeriebilder was intended: for the Viennese court, and especially his brother Ferdinand iii who had married a Gonzaga, he had himself depicted with the vast collection of Italian paintings; for his Spanish cousin, king Philip iv of Spain, he provocatively had Titian’s “poems” prominently on display, possibly including works already bought by his predecessors, such as the Diana and Callisto. There are very few Galeriebilder concentrating on Nordic painting. Y Another instrument used to publicise art works was the Theatrum Pictorum from 1660, which also focused on Italian, and especially Venetian, painting, undertaken by David Teniers in circumstances that were far from ideal because of the sudden departure of the archduke from Brussels in 1656 with part of the collection. Apart from the complex procedure of getting various artists (including Lucas Vostermann, Nikolaus van Hoy, Jan van Troyen, Peter Lisebetten and others) to make engravings based on very small copies painted by Teniers himself, this collection of engravings is still of enormous value in documentary terms, and it also helps us identify works that, over the centuries, have been given away, removed and stolen from the imperial collection. And it also offers us a glimpse of the new Stallburg layout. In aesthetic terms, it would be hard not to agree with the famous physician and collector Charles Patin who, in 1673, criticised the quality of the prints, considering them “copies that deform the originals and alter the most beautiful things in the world: all one sees are the mistakes of the artist, and none of the excellence of these grand ideas”. The non-visual tool par excellence, the most important of all, is the inventory for the archduke’s collection. Dated 1659, it is still now an important element in evaluating attributions. In some cases, it is extraordinarily different from Bartolomeo della Nave’s lists, Hamilton’s Inventories and the Theatrum Pictorum that had come out little more than 20 years before. Thanks to these, it 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 107 is possible, for example, to reconstruct the presence of masterpieces such as Veronese’s Judith (fig. 1), documented by Teniers (fig. 10), and engraved in the following inventories (figs. 9, 11). Along with about 517 Italian paintings, this inventory contains 800 Dutch and German paintings, 542 sculptures, little bronzes and other objects, and 343 drawings. Other collection complexes, such as the famous collection of tapestries and religious items, underline just how universal, if not encyclopaedic, were the archduke’s principles. Italian works also ended up in the Habsburg collections via the Tyrol line, i.e. the archduke Ferdinand Charles, who married Anna de’ Medici: not only the extraordinarily famous Madonna of the Meadow by Raphael and Perugino’s Baptism of Christ, but also Giorgione’s Boy with an Arrow, which Michiel had seen in 1531 “at the home of M Zuan Ram”. Y It would seem that, in the following century, Charles vi and MarieThérèse indirectly contributed to the permanent loss of Venetian works. In 1732, in fact, the emperor sent a considerable group of works (mainly from the Leopold Wilhelm collection) to Prague. These works included Pordenone’s Resurrection of Lazarus and Tintoretto’s Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery, still now in Prague. Works by Giorgione, or attributed to him, in the Bartolomeo della Nave sale list, including The Birth of Paris, Tarquin and Lucretia and others, seem to have fallen victim to the need to decorate the Pressburg and Budapest residences. Yet others, such as Titian’s Christ Crowned with Thorns, ended up in the Bruckenthal Collection in Hermannstadt (Sibiu). Y The famous exchange between the Habsburg brothers took place in the late 18th century. The emperor Francis and Ferdinand iii the grand-duke of Tuscany were inspired by new “scientific” criteria for the reorganisation of the Habsburg and de’ the tale 0020.saggi.qxd 107 a predilection that perhaps begins in 1533, with titian 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 10. David Teniers, Theatrum Pictorium, Vienna Kunsthistorisches Museum. La prima figura a destra, nella terza fila dall’alto, è la Giuditta di Veronese (fig. 1). David Teniers, Theatrum Pictorium, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. The first figure on the right, in the third row from the top, is Veronese’s Judith (fig. 1). 11. Frans von Stampart e Anton von Prenner, Prodromus, tav. 7. Frans von Stampart and Anton von Prenner, Prodromus, table 7. 108 11:27 Pagina 108 Medici collections; the main aim was therefore to give a more balanced view of the historical aspects of the schools. Even if the paintings that came from Florence, including Bronzino’s Holy Family, Pietro da Cortona’s Return of Hagar, Cigoli’s Lament, Salvator Rosa’s Astraea, and Allori’s Christ with the Virgin and St Martha, certainly enriched the collections, it must unfortunately be pointed out that other works were lost (Giovanni Bellini’s Holy Allegory, Titian’s Flora and Madonna of the Roses, Dürer’s so-called Gattamelata, Adam and Eve and Adoration), and we should consider ourselves very lucky indeed that Titian’s Nymph and Shepherd, a very important late work in the Viennese collection, was refused by Florence at the time. Other Veneto works were “lost” during the Napoleonic period, some of which are still in France (including two paintings by Bassano, now in Dijon). Y An equally inglorious chapter deals with the 19th-century transfer of works from Venice to the Viennese court. One such transfer took place in 1816, when 14 Veneto works were transferred from the various Accademia and Commenda di Malta deposits, and another in 1838, when a more consistent group of 50 paintings in 18 crates of paintings from the churches and convents suppressed in the Napoleonic era was moved to Vienna. What’s more, under the direction of the prince of Metternich, another set of works was chosen and sent to the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. As if this weren’t enough, the Austrian government also organised the expedition of a group of Veneto works to decorate churches in the impoverished Bukovina region of the empire. There is also another, murky incident linked with this of a partial restitution in 1866, which is extremely damaging both for the Habsburgs and the Italians, especially considering the unpleasant aftermath in 1919, just after the end of the first world war. Even if they were not first-rate paintings, we can still see, in the old images of the rooms of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, paintings that can now be seen in the Quadreria at Venice’s Accademia, in 22-07-2009 12. Francesco Guardi, La festa della Sensa in piazza San Marco, Vienna Kunsthistorisches Museum. Francesco Guardi, The Feast of the Sensa in St Mark’s Square, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. 11:27 Pagina 109 the Palladio corridor. Much more pleasant for the now state-run Museum was, on the other hand, the possibility of buying, between the two world wars, very important works from the Venetian 18th century, including two famous paintings by Tiepolo for Ca’ Dolfin and Francesco Guardi’s Miracle of a Dominican Saint (the museum also owned his Feast of the Ascension, fig. 12). Y A specific evaluation of the importance of Veneto painting, through its organisation and an evaluation of its position within the Habsburg collection, was undertaken as late as about 1780, when Christian Von Mechel was called upon to present a historical-artistic project for a new presentation of the imperial collection’s paintings at the Belvedere, built buy Eugenio of Savoy and then bought by Marie-Thérèse. Von Mechel had just reorganised the Düsseldorf museum according to new historical-artistic canons, presenting works according to chronological criteria and ordered according to artistic schools. His layout, in fact, began with two rooms dedicated to Venetian painting. And one of my first tasks as curator of Italian painting at the Kunsthistorisches Museum was also to redistribute the collection throughout the newly refurbished rooms. Anything in the preceding layout that began with Raphael and the Florentine Renaissance, i.e. Fra Bartolomeo and Andrea Sarto, along with the masterpieces of the Emilian paintings of Correggio and Parmigianino, I took as good, almost obligatory to underline the greater and more marked preferences and interests of the Habsburgs’ collections – that is, Venetian painting. I therefore tried to concentrate in three large rooms the “pilasters” of 16th-century Veneto painting, i.e. Titian, Veronese and Tintoretto, including Palma the Elder and Palma the Younger, Paris Bordone and the Bassanos; I left the less monumental works by Antonello da Messina, Bellini, Giorgione and Lorenzo Lotto for the side galleries, which run alongside the large halls. Even though this layout dates back 20 years, and already in embryonic form in the post-world war first era, it still seems to me to be valid and coherent: it is the revealing mirror not only of the tastes, but also of the collecting history, of the Habsburgs. the tale 0020.saggi.qxd 109 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 110 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 111 compravendite e trasferimenti dei mesi, capolavoro di leandro dalla laguna fino agli asburgo: i tanti viaggi di un ciclo di 12 bassano (ma uno è sparito) Francesca Del Torre Scheuch 1. Leandro Da Ponte detto Bassano, Febbraio, particolare, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. Leandro Da Ponte, known as Bassano, February, (detail), Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. Y La Gemäldegalerie del Kunsthistorisches Museum di Vienna possiede senza dubbio la raccolta più consistente di quadri dei Bassano fino a oggi nota. Essa testimonia del successo di quei maestri in tutta Europa non solo presso i contemporanei, ma anche nei secoli successivi. Sono 86 i lavori riferibili all’operosa famiglia dei Da Ponte, di cui ben 10, secondo le più recenti ricerche, sono attribuibili con certezza al grande Jacopo (1510 circa-1592). Dalle famose stagioni, alle parabole evangeliche; dai notturni, agli opulenti mercati: la raccolta offre una rassegna dei soggetti trattati dalla bottega bassanesca talmente esauriente, da farne imprescindibile strumento di studio (fig. 2). Tra questi, merita particolare attenzione una serie quasi completa che raffigura i mesi dell’anno. Raramente accessibile al pubblico del museo, decora una sala destinata abitualmente a conferenze, che da qualche anno porta il nome di Bassano Saal in omaggio, appunto, alla ricchezza della raccolta. E come le tele siano giunte a Vienna è quanto ci proponiamo di raccontare, un po’ immaginando, un po’ ricostruendo sulla base di notizie a dire il vero piuttosto frammentarie, specie per quanto riguarda il loro primo ventennio di vita, ma sempre con il sostegno delle Maraviglie dell’arte di Carlo Ridolfi. Y I dipinti rappresentano i mesi dell’anno (fig. 3) attraverso la raffigurazione dei lavori della campagna caratteristici per ognuno di essi; nel caso dei mesi invernali, come gennaio, febbraio e marzo in cui le opere agricole segnavano una pausa, attraverso il ritorno dalla caccia, il carnevale con la caccia al toro e una scena di mercato durante la Quaresima. Ogni tela è contraddistinta dal segno zodiacale corrispondente, visibile in alto tra le nuvole (fig. 4). La composizione, pervasa da una luce crepuscolare, è organizzata su piani paralleli digradanti verso il paesaggio nello sfondo, concluso all’orizzonte dalla massa azzurrina della montagna, probabilmente il monte Grappa, su cui l’occhio si sofferma e riposa. Nel primo piano, l’interesse di Leandro (Bassano, 1557- la curiosità 0020.saggi.qxd 111 compravendite e trasferimenti dei mesi, capolavoro di leandro 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 2. Jacopo Da Ponte, detto Jacopo Bassano, Adorazione dei Magi, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. Jacopo Da Ponte, known as Jacopo Bassano, Adoration of the Magi, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. 112 11:27 Pagina 112 Venezia, 1622) si rivolge alla descrizione, precisa e accurata, delle attività dei contadini, e si sbizzarrisce nella rappresentazione di frutta e verdura, ma anche delle varietà di pesci e dolciumi, tutti perfettamente identificabili. Particolare attenzione è inoltre dedicata alla resa, fin nei dettagli minuti, degli attrezzi da lavoro, degli oggetti d’uso comune e dell’abbigliamento, tanto che i dipinti possiedono un notevole valore documentario. Vienna custodisce oggi 9 dipinti; la Galleria del Castello di Praga ha i mesi di settembre e ottobre; dicembre si trovava, negli anni ottanta del Novecento, sul mercato antiquario. Y Certamente i Mesi di Leandro costituiscono, per lo straordinario valore decorativo, la qualità delle opere e, non da ultimo, la grandezza del formato (145 × 215 cm) uno tra i cicli più spettacolari di questo tipo, anche perché restano un caso quasi isolato. Le tele sono tutte firmate «Leander Bassanensis faciebat», formula abituale della famiglia. Nel caso di Leandro, questo elemento ci dà il termine ante quem per la datazione della serie. Nell’aprile 1595, Marino Grimani, succeduto come doge a Sebastiano Venier, «[…] perché si predicava dall’universale la bellezza 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 113 de’ suoi [eseguiti da Leandro] ritratti volle […] esser da lui ritratto, che fu posto nelle stanze della Procuratoria, del quale così quel Principe si compiacque che lo creò suo cavaliere». Così, dopo il 1595, Leandro iniziò a firmare le sue opere con il titolo di “aeques” (fig. 5). E uno vanitoso come lui che, descrive vivacemente il Ridolfi, quando usciva di casa si faceva accompagnare dagli allievi «un de’ quali gli portava lo stocco dorato, l’altro il memoriale per ridursi a mente le cose che aveva a fare, dimostrando grandezza e splendore in ogni sua atione», difficilmente avrebbe perso un’ottima occasione per fregiarsi del titolo. Y I Mesi sono opere certamente concepite per un committente importante, e riesce difficile pensare che la bottega avesse lavorato ad un’impresa decorativa di così grande rilievo nella speranza di piazzare prima o poi la serie sul mercato, secondo la pratica seguita spesso da Jacopo per le sue scene pastorali. Alle spalle doveva esserci un progetto, e forse un committente: e al proposito, ci vengono in aiuto le parole dello stesso Francesco Bassano in una sua lettera a Niccolò Gaddi – uno dei collezionisti fiorentini più importanti, soprattutto di disegni, del Cinquecento – datata 25 maggio 1581, sulla cui importanza aveva già attirato l’attenzione Miguel Falomir Faus. Questa, citatissima dagli storici dell’arte per l’accenno alla pratica disegnativa di Jacopo e Francesco, è pubblicata nella Raccolta di lettere sulla pittura, scultura e architettura di Giovanni Bottari, stampata a Roma nel 1759. Era inoltre già nota a Giambattista Verci, biografo settecentesco di Jacopo, che la riassume nelle sue Notizie intorno alla Vita e alle opere de’ Pittori Scultori e Intagliatori della Città di Bassano, uscite a Venezia nel 1775. Y Un brano di questa missiva, in particolare, è di grande importanza: «Già buoni giorni fa avvisai a V.S. ill., come ella sa che desideravo far li dodici mesi dell’anno; e perché vedo in questi quadri grandi, del palazzo di questi ill. Signori, venir in modo, che la prego di far ancor di qui qualche cosa, che le figure possan venir grandi, per mostrar l’arte a modo mio; sicché la prego con qualche occasion di qualche suo amico favorirmi come ho fede, che benché non l’avvisasse, non mancherà sapendo che V.S. ill. purtroppo è affezionato, a cui si diletta di perficer in le virtù. Quanto poi al prezzo, farò sempre ogni cortesia, quando che V.S. mel commetterà. E non essendo con questa da dir altro a V.S. ill., di cuore la prego a tenermi nel numero de’ suoi servitori». Un committente fiorentino, non meglio speci- la curiosità 0020.saggi.qxd 113 compravendite e trasferimenti dei mesi, capolavoro di leandro 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 3. Leandro Da Ponte detto Bassano, Gennaio, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. Leandro Da Ponte, known as Bassano, January, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. 4. Leandro Da Ponte detto Bassano, Febbraio, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. Leandro Da Ponte, known as Bassano, February, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. 114 11:27 Pagina 114 ficato, desiderava avere dalla bottega dei Bassano dei quadri grandi per una sala del proprio palazzo, e Francesco prega dunque Gaddi di farsi tramite presso costui della sua proposta di dipingere i Mesi – un’idea che da qualche tempo coltivava – e con figure grandi a sufficienza per «mostrar l’arte», secondo il suo desiderio. Y Questa descrizione si adatta sia al ciclo viennese di Leandro sia a una serie non completa dei Mesi, di grandi dimensioni (150 × 245 cm), firmata da Francesco Bassano (Bassano, 1549-Venezia, 1592), di proprietà del Museo del Prado, ma in deposito presso varie istituzioni madrilene. Le tele spagnole, presentate da Miguel Falomir Faus in una mostra nel 2001, hanno, non a caso, una provenienza fiorentina: furono inviate nel settembre del 1590 alla corte spagnola come dono diplomatico per conto di Ferdinando de’ Medici; rimaste per circa un decennio all’ambasciata fiorentina a Madrid, furono infine offerte in dono nel 1601 al duca di Lerma. Sembra dunque quasi certo che queste tele siano quelle di cui parla Francesco nella lettera a Gaddi, e non è escluso che il committente fosse proprio Ferdinando, al quale Gaddi era molto vicino. D’altronde, il Medici collezionò opere di Francesco già durante il suo cardinalato a Roma, e nel 1584, attesta Lorenzo Borghini nel suo Riposo, Francesco era già noto a Firenze e a Roma. Tra Francesco e Firenze esisteva dunque un legame, che spiega anche i contatti con Niccolò Gaddi che egli doveva aver conosciuto prima del 1581. Y I Mesi spagnoli e viennesi costituiscono le uniche serie – variamente complete – che siano giunte fino a noi (fig. 6). Nonostante l’inventario della bottega di Jacopo Bassano elenchi cinque tele di grandi dimensioni raffiguranti appunto alcuni mesi dell’anno, non conosciamo finora altre serie prodotte dalla bottega con le stesse misure. Esistono invece versioni di minori dimensioni, realizzate per lo più in ambito nordico, che testimoniano la ricezione del tema nel tardo Seicento oltre le Alpi. L’esistenza del secondo ciclo dipinto da Leandro dimostra come i due fratelli abbiano strettamente collaborato, probabilmente a Venezia, dove Francesco aveva bottega dal 1578. I due giovani Bassano realizzarono opere che, sotto il profilo tematico e iconografico, derivano senza dubbio dai modelli di Jacopo; ma, in realtà, sono qualcosa di completamente diverso, costituendo la traduzione in chiave narrativa e decorativa, pre-secentesca, del linguaggio paterno. 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 115 Y Se il ciclo spagnolo è nominato nella corrispondenza Bassano-Gaddi, la serie viennese corrisponde a quella descritta da Carlo Ridolfi nelle sue Maraviglie dell’arte, che la attribuiva a Jacopo Bassano. «A Ridolfo ii imperatore [Jacopo] mandò i dodeci mesi, ne’ quali erano divisate tutte quelle attioni che occorrono per l’anno; che così piacquero à quella Maestà, che sempre mai amò i pittori, e furono de’ suoi più cari Bartolameo Spranger e Gioseppe Heintz, qual creò suo cavaliere, e di lui vive il figliuolo del medesimo nome in Venetia ingegnoso Pittore, che perciò ne ricercò Jacopo à suoi servigi; ma egli non volle cangiare la picciola sua Casa co’ Palagi reali; quali si videro per lungo tempo nella Galleria di Praga» (fig. 7). Le notizie di Ridolfi su Jacopo si basavano su informazioni dirette fornitegli probabilmente dagli eredi del pittore, presenti a Venezia. Nel caso dei Mesi, potrebbe aver avuto importanza il pittore Joseph Heintz il giovane, attivo a Venezia, figlio di Joseph, già pittore di corte di Rodolfo ii a Praga. Una frase, in particolare, ci dice che Ridolfi aveva a disposizione informazioni fornite da qualcuno in contatto con la corte praghese, o che addirittura aveva visto la galleria. Che i Mesi «[…] si videro per lungo tempo nella Galleria di Praga» significa sia che i dipinti erano stati esposti nella Galleria del castello, sia che quando Ridolfi scrive, le tele non erano più lì. E questo corrisponde alla verità. Y Non sappiamo quando e come i dipinti siano giunti a Praga, la curiosità 0020.saggi.qxd 115 compravendite e trasferimenti dei mesi, capolavoro di leandro 0020.saggi.qxd 116 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 116 né sono state finora rinvenute testimonianze documentarie su un’eventuale commissione. Ma è certo che il soggetto si addiceva parecchio al gusto di Rodolfo. In due dispacci del 4 e 12 luglio 1604, l’ambasciatore del duca di Savoia, conte Carlo Francesco di Lucerna, si riferisce ai due dipinti raffiguranti «mercati della frutta et pescaria», opere di un pittore neerlandese attivo a Cremona, inviati dal Savoia all’imperatore a Praga. Trasmette ciò che ha saputo dal «pitore di S.M. il quale li riferse che hieri l’imperatore stete due ore e mesa assentato senza moversi guardar li quadri delli mercati di frutta e pescaria mandati da V. A. […] ha fatto scrivere a Cremona per sapere se il pittore fusse vivo per tirarlo al suo servitio...». D’altra parte, l’imperatore aveva suoi agenti un po’ in tutta Europa, che a stento riuscivano a stare al passo con le sue insaziabili brame collezionistiche. Oltre a dipinti, ricercavano oggetti preziosi per la Kunstkammer e le più varie curiosità naturali, animali rari, piante esotiche. Sappiamo che Rodolfo invia più volte il pittore di corte Hans von Achen ad acquistare quadri in Italia, e che intratteneva rapporti con Hans Rottenhammer a Venezia, il quale acquistava e restaurava dipinti per lui a inizio Seicento. Inoltre, la comunità germanica a Venezia era sicuro punto di riferimento: i Fugger finanziavano gli acquisti del sovrano e i segretari – ad esempio Bernardino Rosso – si occupavano delle spedizioni da Venezia a Praga delle cose più svariate, dalle botti di malvasia, ai leopardi. Infine, lo stretto rapporto tra Rodolfo e il gioielliere Jacob König, imparentato con la famiglia degli Ott, mercanti tedeschi a Venezia, costituiva probabilmente un altro importante canale per gli acquisti in laguna. Y Le vicissitudini del ciclo sono ricostruibili dal punto di vista 22-07-2009 5. Leandro Da Ponte, detto Bassano, Gentiluomo con scultura, Milano, collezione Koelliker: il dipinto è firmato «Leander a Ponte / Bas. / Aeques/ F». Leandro Da Ponte, known as Bassano, Gentleman with Sculpture, Milan, Collezione Koelliker: the painting is signed “Leander a Ponte / Bas. / Aeques/ F”. 11:27 Pagina 117 documentario solo dal 1617, quando si accenna, per la prima volta, a una serie dei dodici Mesi conservati nella reggia di Neustadt (fig. 8). In questa cittadina a sud di Vienna, oggi Wiener Neustadt, la famiglia imperiale trascorreva spesso alcuni periodi, utilizzandola come residenza estiva, o rifugio dalle pestilenze che minacciavano la capitale. Qui, nel 1614, nasce l’arciduca Leopoldo Guglielmo, figlio di Ferdinando ii e di Maria di Baviera: figlio cadetto, è destinato alla vita religiosa, e non sempre segue la famiglia nei viaggi. A Neustadt lontano dalle tentazioni viennesi, egli riceve dal 1628 la sua educazione. Tale residenza, giardino zoologico compreso – «Schloss und Burg samt dem Tiergarten» – gli è donata dal padre nel marzo 1630. Dei beni custoditi in questo castello tra il 1616 e il 1618 si redige un inventario, in seguito a un incendio scoppiato nell’agosto 1616. Al numero 170, in una camera vicino alla cucina, figurano «[…] zwelf stuck gemähl, als die zwelf monat, von Bassan herkomen», cioè dodici dipinti con i mesi dell’anno di Bassan[o] (fig. 9). Y Ecco dunque riemergere con una certa sicurezza il nostro ciclo. Ma i dodici Mesi (fig. 10), come erano arrivati a Neustadt? È probabile che le tele vi siano state trasportate dopo la morte di Rodolfo ii (fig. 11). Dal 1612 in poi, succeduto al fratello, l’imperatore Mattia, che intendeva dichiaratamente riportare a Vienna la sede dell’impero, fa trasportare, provvidenzialmente, un grande numero di opere d’arte della collezione del fratello da Praga a Vienna, di cui una parte – che non figura negli inventari storici del 1610-1619 – è forse smistata nelle varie residenze. Si è detto provvidenzialmente, perché la manovra, organizzata per quanto possibile di nascosto e soprattutto senza lasciare alcun cenno inventariale ufficiale, salverà alcuni tra i maggiori capolavori delle collezioni imperiali dai saccheggi di Praga, perpetrati dai Sassoni (1632) e poi dagli Svedesi (1648). Tanto che la regina Cristina, che aveva dato precise istruzioni alle sue truppe di portare a Stoccolma i capolavori già di Rodolfo ii, non riesce a celare la delusione e il dispetto quando, esaminato il bottino di guerra, constata l’assenza, ad esempio, di alcuni Correggio, dei Parmigianino, e di tanti altri dipinti che, ancor oggi, si ammirano al Kunsthistorisches di Vienna. Y Non si sa esattamente quando le dodici tele (fig. 12) siano giunte a Neustadt. È però certo che il 14 luglio 1659 si trovavano invece a Vienna, poiché sono elencate dal famoso inventario della collezione redatto da Anton Van der Baren. Nella primave- la curiosità 0020.saggi.qxd 117 compravendite e trasferimenti dei mesi, capolavoro di leandro 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 6. Leandro Da Ponte, detto Bassano, Marzo, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. Leandro da Ponte, known as Bassano, March, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. 7. Leandro Da Ponte, detto Bassano, Aprile, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. Leandro da Ponte, known as Bassano, April, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. 118 11:27 Pagina 118 ra del 1656, l’arciduca rinuncia al governatorato dei Paesi Bassi: abbandona Bruxelles con la sua splendida collezione, trasferita a Vienna in due spedizioni successive che a novembre 1656 si riuniscono a Passau. Nel 1658 iniziano i lavori di ristrutturazione del piano superiore della Stallburg, e nel 1659 le opere trovano sistemazione nell’edificio, alle spalle della Hofburg, verso il cuore della città, che al piano terreno ospitava le stalle imperiali. Non era un caso che ai piani superiori di tali edifici trovassero collocazione raccolte d’arte: per le stalle era prevista infatti una sorveglianza costante antincendio, utile per la tutela delle opere. Del resto, entrambe le strutture richiedevano, dal punto di vista architettonico, ambienti sviluppati in lunghezza, con superfici murarie estese. Nell’inventario troviamo ai numeri 370-381 i nostri Mesi: «Zwelff Landschafften von Öhlfarb auf Leinwath einer Größen, darunder eine etwas kleiner, die zwelff Monath des Jahrs. In schwartzglatten Ramen, die Höhe 7 Spann 9 finger vnndt Braidte 11 Spann 1 Finger; eines darunter gar schadhaft. Alle von dem jungen Bassan Original»[164,32 × 230,88 cm]. E cioè «12 paesaggi ad olio su tela tutti della stessa grandezza, di cui uno un po’ più piccolo, i dodici mesi dell’anno. In cornice nera alti 7 spanne e 9 dita e larghi 11 spanne e 1 dito; uno di questi è piuttosto danneggiato. Tutti originali del giovane Bassano» (fig. 13). Questo, tra l’altro, è un inventario assai dettagliato e preciso che, oltre a fornire una corretta attribuzione al giovane Bassano – cioè Leandro – indica con una certa precisione le misure, anche se comprensive della cornice, e fornisce annotazioni sullo stato di conservazione. La descrizione, unica stranezza, non fa cenno dei segni zodiacali, forse ridipinti. Ecco dunque come Leopold Wilhelm, figura di spicco del collezionismo asburgico – oltre che vescovo, soldato e politico, con un ruolo fondamentale nella strategia familiare della guerra dei trent’anni – è stato determinante nei confronti di questo ciclo bassanesco, che ben conosceva e apprezzava dai tempi della sua giovinezza a Neustadt. Y Tuttavia, il soggiorno viennese delle tele dura meno di un secolo: infatti, il loro destino itinerante le riporta a Praga. Il Settecento è un secolo di grandi spostamenti e riorganizzazioni nelle raccolte imperiali. Con Carlo vi, la regione boema perde importanza politica e si allentano i legami con la nobiltà locale. Anche il castello di Praga con le sue collezioni, venuta a cadere o quasi la funzione di rappresentanza, è non solo trascurato, ma vittima del nuovo indirizzo autocelebrativo del sovrano. Carlo vi 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 119 la curiosità 0020.saggi.qxd 119 compravendite e trasferimenti dei mesi, capolavoro di leandro 0020.saggi.qxd 120 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 120 inaugura un processo di accentramento, fusione e riorganizzazione delle collezioni imperiali nella capitale, proseguito coerentemente dalla figlia Maria Teresa con l’apertura al pubblico delle Gallerie imperiali al Belvedere nel 1781. In questo spirito, a più riprese negli anni, vengono fatti affluire, anche da Praga, molti dipinti ritenuti adatti ad arricchire e completare la collezione viennese; per risarcire i prelievi e per non lasciare sguarnita la residenza sono inviate opere allora ritenute di minore importanza. In questo contesto i Mesi, evidentemente non particolarmente apprezzati nella temperie barocca della corte di Carlo vi, vanno a Praga nel 1732, insieme ad altri 32 dipinti. Y Il processo si protrae anche nel secolo successivo, per concludersi nel 1894, quando avviene l’ultimo trasferimento di dipinti da Praga nel Kunsthistorisches Museum sul Burgring, inaugurato nel 1891. Al 1894 risale dunque l’ultima spedizione da Praga, che comprende ben 32 dipinti dei Bassano o ad essi attribuiti: un terzo dunque dell’attuale collezione. Tra questi, nove tele dei Mesi la cui appartenenza al ciclo non era stata riconosciuta, forse perché il segno zodiacale era stato ridipinto su una parte dei quadri. Tale mancato riconoscimento dell’unità del ciclo è certamente responsabile del fatto che tre dipinti, sparsi nei vari locali del castello e così sfuggiti agli ispettori, siano rimasti a Praga. Y È l’ultimo tra i viaggi dei Mesi di Bassano: partiti da Venezia a fine Cinquecento, adornano la Galleria di Praga per circa due decenni. Scampati a guerre e saccheggi, finiscono, forse dimenticati, a Neustadt da dove Leopold Wilhelm li fa rientrare a Vienna collocandoli nella Stallburg. In occasione del riallestimento in gusto barocco della galleria voluto da Carlo vi, le tele si mettono per la seconda volta in viaggio per Praga, loro destinazione originaria, da dove ritornano definitivamente a fine Ottocento. Come dimostra la loro storia, i Mesi furono certamente apprezzati da Rodolfo ii e da Leopoldo Guglielmo, due tra i maggiori collezionisti della casa d’Austria. Proprio sulla base dei trasferimenti che si è cercato di ricostruire, essi testimoniano le scelte del grande collezionismo asburgico che è riuscito a consegnarci intatta e continuamente arricchita da integrazioni e continui scambi – anche al suo interno – una delle più straordinarie e complete raccolte al mondo. 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 121 sales and transfers of “months”, leandro’s masterpiece, revealed from venice to the habsburgs: the many voyages of a cycle of 12 bassanos (but one is missing) curiosity 0020.saggi.qxd Francesca Del Torre Scheuch Y The Gemäldegalerie of Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum has what is without a doubt the greatest collection of Bassanos ever known. It is a demonstration of the great success of these maestros throughout Europe, not only among their contemporaries, but also in the ensuing centuries. There are 86 works that can be traced back to the industrious Da Ponte family, of which 10, according to recent research, can certainly be attributed to the great Jacopo (c. 1510-1592). The collection offers an overview of the subjects dealt with by the Bassano workshop (the famous seasons, the evangelical parables, the nocturnes, the opulent markets) that is so exhaustive that it cannot be ignored (fig. 2). Among these, special mention must be made of an almost complete series of the months of the year. Rarely accessible to museum visitors, it decorates a room usually reserved for conferences, and which for a few years now has been called the Bassano Saal in deference to the importance of the collection. How these paintings came to Vienna is what I aim to relate, using a touch of imagination and doing some reconstructing based on hard facts that, to tell the truth, are rather fragmentary, especially in reference to the first two decades; but all of this using Carlo Ridolfi’s Maraviglie dell’arte. Y The paintings represent the months of the year (fig. 3) through a figuration of country jobs characteristic of each, except for the winter months, such as January, February and March, which depict a test from the rural labours, and which are represented by a return from a hunting trip, carnival celebrations and bull hunting, and a Lent market scene. Each painting is characterised by its corresponding astrological sign, which can be seen in the clouds (fig. 4). The composition, pervaded by a crepuscular light, is arranged receding into the landscape, parallel to the picture surface: the horizon is formed by the bluish mass of a mountain (probably Monte Grappa), where the eye rests. In the foreground, Leandro (Bassano 1557 - Venice 1622) 121 sales and transfers of “months”, leandro’s masterpiece, revealed 0020.saggi.qxd 122 22-07-2009 11:27 Pagina 122 22-07-2009 8. Leandro Da Ponte, detto Bassano, Maggio, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. 8. Leandro Da Ponte, known as Bassano, May, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. 9. Leandro Da Ponte, detto Bassano, Giugno, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. Leandro Da Ponte, known as Bassano, June, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. 11:27 Pagina 123 is interested in the precise and accurate description of the peasants’ activities, and he takes pleasure in representing fruit and vegetables as well as the different varieties of fish and sweets, all easily identifiable. He also pays particular attention to the minutely detailed rendering of work tools, commonly used objects and clothing – so much so, that the paintings also have a marked documentary value. Vienna now possesses 9 paintings; the Gallery at the Castle in Prague has September and October; December was last seen on the antiques market in the 1980s. Y Certainly, Leandro’s Months, because of their extraordinary decorative value, the quality of execution and their enormous format (145 × 215 cm), are one of the most spectacular and unique cycles of their type. The canvases have all been signed “Leander Bassanensis faciebat”, the family’s habitual formula. In Leandro’s case, this element provides the ante quem term for the dating of the series. In April, 1595, the doge Marino Grimani, who followed Sebastiano Venier, “because [Leandro’s] portraits were universally hailed, he wanted [...] to be painted by him, and his portrait was placed in the Procuratie, and of this portrait the Prince was so pleased that he made him a knight”. Hence, Leandro began signing his works with the title “aeques”, fig. 5, (i.e. “knight”) after 1595. And, according to Ridolfi’s vivacious description, whenever he went out he made sure he was accompanied by his students, “one of whom carried his golden swordstick, another his diary containing a rundown of all the things he had to do, demonstrating grandeur and splendour in every single action” – so conceited an individual was hardly likely not to use his title. Y The Months is a work that was undoubtedly conceived for an important patron, and it is hardly likely the workshop would have worked on such an impressive decorative undertaking in hopes of selling the series sooner or later, according to the practice often followed by Jacopo for his pastorals. There must have been a prior project, and even a commission, a fact which is corroborated by something Francesco Bassano wrote in a letter to Niccolò Gaddi (one of the most important Florentine collectors, especially of 16th-century drawings), dated May 25, 1581, the importance of which has already been underlined by Miguel Falomir Faus. The letter, often cited by art historians because of the light it sheds on Jacopo and Francesco’s drawing practice, was published in Giovanni Bottari’s Raccolta di lettere sulla pittura, scultura e ar- curiosity 0020.saggi.qxd 123 sales and transfers of “months”, leandro’s masterpiece, revealed 0020.saggi.qxd 124 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 124 chitettura, published in Rome in 1759. Giambattista Verci, Jacopo’s 18th-century biographer, was familiar with the letter, and he sums it up in his Notizie intorno alla Vita e alle opere de’ Pittori Scultori e Intagliatori della Città di Bassano, which came out in Venice in 1775. Y One part of the letter is particularly important: “A good number of days ago I advised your Lordship, as you know, that I desired to make the twelve months of the year; and because I see these large paintings for the residence of these illustrious sirs to be most suitable, I pray you to do of your best so that I can paintfigures in large size to better show my art; I therefore pray you to find some occasion where some friend of yours may favour me as I have faith, so that if you should ask this then he will not deny knowing that your Lordship is devoted [...]. As for the price, then, I will do of my utmost, when your Lordship do ask it of me. Having nothing else to communicate to your Lordship, I sincerely pray thee to consider me beholden to you”. An otherwise anonymous Florentine patron asked the Bassanos’ workshop for large paintings for a room in his house, and Francesco therefore requested that Gaddi act as intermediary in communicating his proposal to paint the Months – an idea he had been mulling over for a while – and large enough for him to be able to “show his art”, according to his desire. Y This description is in keeping both with Leandro’s Viennese cycle and an incomplete series of very large Months (150 × 245 cm) signed by Francesco Bassano (Bassano 1549 - Venice 1592), owned by the Prado but deposited in various institutions in 22-07-2009 10 e 10a. Leandro Da Ponte detto Bassano, Luglio (in due parti), Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. Leandro Da Ponte, known as Bassano, July (in two parts), Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. 11:28 Pagina 125 Madrid. The Spanish paintings, presented by Miguel Falomir Faus in an exhibition in 2001, have, not casually, a Florentine provenance: they were sent in September, 1590, to the Spanish court as a diplomatic gift on behalf of Ferdinando de’ Medici; they spent about a decade in the Florentine embassy in Madrid, and were finally offered as a gift to the duke of Lerma in 1601. It therefore seems almost certain that these paintings are those mentioned by Francesco in his letter to Gaddi was very close, and it can not be excluded that the purchaser was Ferdinando himself, whom Gaddi. What’s more, Ferdinando de’ Medici had already collected works by Francesco when he was a cardinal in Rome, and in 1584, as stated by Borghini in his Riposo, Francesco was already well known in Florence and Rome. There was therefore a link between Francesco and Florence, which would also explain contact with Niccolò Gaddi, whom he must have met before 1581. Y The Spanish and Viennese Months are the only (variously completed) series that are still extant (fig. 6). Despite the fact the inventory of Jacopo Bassano’s workshop lists five large paintings depicting months of the year, we are as yet unfamiliar with other series produced in the workshop with the same dimensions. There are, however, smaller versions, painted mainly in Nordic countries, which prove the theme was taken up north of the Alps in the late 17th century. The existence of the second cycle painted by Leandro demonstrates how the two brothers collaborated, probably in Venice, where Francesco had a workshop from 1578. curiosity 0020.saggi.qxd 125 sales and transfers of “months”, leandro’s masterpiece, revealed 0020.saggi.qxd 126 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 126 The two young Bassanos painted works that, from a thematic and iconographic point of view, doubtless derive from Jacopo’s models, but that, in fact, are completely different, constituting a translation of their father’s language into pre-17th century narrative and decorative terms. Y If the Spanish cycle is mentioned in the Bassano-Gaddi correspondence, the Viennese series corresponds to the one described by Carlo Ridolfi in his Maraviglie dell’arte, where it is attributed to Jacopo Bassano. “To Rudolf ii the emperor [Jacopo] sent the twelve months, in which were devised all those actions that occur during the year; they were so appreciated by that Majesty that he ever after loved artists, and his closest became [...] Spranger and [...] Heintz, whom he made his knight, and his little son of the same name lives with him in Venice; but he did not want to change his little House with royal Palaces; which were seen for much time in the Prague Gallery” (fig. 7). Ridolfi’s information on Jacopo was based on direct facts probably supplied by the painter’s heirs in Venice. As for the Months, an important role may have been played by the painter Joseph Heintz the younger, who was active in Venice and was the son of the former court painter for Rudolf ii in Prague. One reference in particulars indicates that Ridolfi had information supplied by someone in contact with the Prague court, and had even seen the gallery. The statement the Months “were seen for a long time in the Gallery in Prague” means both that the paintings were exhibited in the castle’s Gallery, and that when Ridolfi wrote the Maraviglie the paintings were no longer there. And this corresponds to the truth. 22-07-2009 11. Hans von Aachen, Ritratto dell’imperatore Rodolfo II, Vienna Kunsthistorisches Museum. Hans von Aachen, Portrait of the Emperor Rudolf II, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. 11:28 Pagina 127 Y We don’t know when or how the paintings got to Prague, nor has any direct documentary testimony been found regarding a possible commission. But it is certain that the subject was very much to Rudolf’s liking. In two despatches, dated July 4 and July 12, 1604 and sent to the emperor in Prague, the ambassador of the duke of Savoy, the count Carlo Francesco of Lucerne, refers to two paintings depicting “fruit and fish markets”, works by a Dutch painter active in Cremona. He transmitted what he had heard from “HM’s painter, who reported that yesterday the emperor spent two and a half hours sitting motionless looking at the paintings of the fruit and fish markets sent by Your Highness [...] he had word sent to Cremona to discover if the painter were alive to ask him to join his service”. On the other hand, the emperor had agents here and there throughout all of Europe, who were hardly able to keep up with his insatiable desire for collecting. Besides paintings, they also sought precious objects for his Kunstkammer and the wildest natural curiosities, rare animals and exotic plants. We know that Rudolf sent the court painter Hans von Achen to Italy on more than one occasion to buy paintings, and that he maintained relations with Hans Rottenhammer who bought and restored paintings for him in the early 17th century in Venice. What’s more, the Germanic community in Venice was a sure point of reference: the Fuggers financed the sovereign’s purchases and various secretaries (such as Bernardino Rosso) would organise shipments from Venice to Prague of the most wide-ranging objects – from malmsey barrels to leopards. Finally, the close relationship between Rudolf and the jeweller Jacob König, who was related to the Ott family (German merchants in Venice), probably constituted another important channel for purchases in the city. Y The vicissitudes of the cycle can be confirmed with documentary evidence only from 1617, when mention is made for the first time of a series of 12 Months conserved in the Neustadt royal palace. In this little town south of Vienna, now called Wiener Neustadt (fig. 8), the imperial family often spent periods of time, either using it as a summer retreat or as a refuge during the plagues that beset Vienna. It was here, in 1614, that the archduke Leopold Wilhelm was born to Ferdinand ii and Maria Anna of Bavaria, and as the youngest son he was destined for a religious life and didn’t always accompany his family when they travelled. Neustadt became his residence, and, cut off from the temptations of Vienna, he received his education here from 1628. The curiosity 0020.saggi.qxd 127 sales and transfers of “months”, leandro’s masterpiece, revealed 0020.saggi.qxd 128 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 128 residence, zoological gardens included (“Schloß und Burg samt dem Tiergarten”), was given to him by his father in March, 1630. Following a fire in 1616, an inventory of all the objects at the residence was drawn up between 1616 and 1618. Listed as numeber 170 in a room near the kitchen, are 12 paintings with the months of the year by Bassan[o] (“zweff stuck gemähl, als die zwelf monat, von Bassan herkomen”) (fig. 9). Y This is a fairly certain reference to our cycle. But how did these 12 Months (fig. 10) end up in Neustadt? The paintings were probably taken there after the death of Rudolf ii (fig. 11). From 1612 on, on succeeding his brother, the emperor Matthias, who declared he wanted to make Vienna the capital of the empire once more, had a large number of works from his brother’s collection providentially transferred from Prague to Vienna, whence a part (not included in the historical inventories of 1610-19) was perhaps apportioned to different residences. “Providentially” because the move, organised as much as possible on the sly and above all without leaving any official inventory, would save some of the greatest masterpieces of the imperial collections from the sack of Prague undertaken by the Saxons (1632) and then the Swedes (1648). And in fact Queen Christina, who had given her troops precise instructions about the masterpieces belonging to Rudolph ii they had to bring home to Stockholm, was unable to hide her displeasure and anger when, on examining the booty, saw that there were no Correggios, Parmigianinos or many other paintings that we can still admire now at Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches. Y We do not know exactly when the 12 paintings (fig. 12) arrived at Neustadt. What is certain, though, is that on July 14, 1659, they were in Vienna, as they were listed in the famous inventory of the collection drawn up by Anton Van der Baren. In the spring of 1656, the archduke gave up the governorship of the Netherlands: he left Brussels with his magnificent collection, which he transferred to Vienna in two separate shipments that were brought together again in Passau in November. In 1658, work began on restructuring the upper floor of the Stallburg, and in 1659 the collection was dislocated to the building just behind Hofburg, near the heart of the city, with the imperial stables on the ground floor. It was not accidental that the upper floors of these buildings housed art collections, as stables were constantly guarded by firemen, which was also perfect for the protection of the works of art. 22-07-2009 12. Leandro Da Ponte, detto Bassano, Agosto, Vienna Kunsthistorisches Museum. Leandro Da Ponte, known as Bassano, August, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. 11:28 Pagina 129 What’s more, both structures required long rooms with wide walls. Our Months are listed in the inventory under numbers 370381: “Zwelff Landschafften von Öhlfarb auf Leinwath einer Größen, darunder eine etwas kleiner, die zwelff Monath des Jahrs. In schwartzglatten Ramen, die Höhe 7 Spann 9 finger vnndt Braidte 11 Spann 1 Finger; eines darunter gar schadhaft. Alle von dem jungen Bassan Original” (164.32 × 230.88 cm). That is, “12 oil on canvas landscapes all the same size, of which one slightly smaller, the twelve months of the year. With black frame, 7 spans and 9 fingers tall and 11 spans and 1 finger wide; one of these is rather damaged. All originals by the young Bassano” (fig. 13). This is a rather detailed and precise inventory that not only provides a correct attribution to the young Bassano (i.e. Leandro), but also indicates with some precision the sizes (albeit including the frame) along with notes on the state of conservation. The only curious point is that it makes no reference to the astrological signs, which have perhaps been repainted. This, then, is how Leopold Wilhelm, a leading figure in the world of Habsburg collecting (as well as being a bishop, soldier and politician, with a fundamental role in the family’s post-Thirty Years War strategy), was a key figure in this Bassano cycle, which he had been familiar with since his childhood in Neustadt. Y However, the paintings remained less than a century in Vienna. In fact, their itinerant destiny would eventually lead them back to Prague. The 18th is a century of great movements and reorganisations within the imperial collections. With Charles vi, the Bohemian region lost its political importance and ties with the local nobility were lost. Even the castle in Prague with its collections, once it had all but lost its diplomatic and formal entertainment functions, was not only neglected, but fell victim to the sovereign’s new self-celebratory bent. Charles vi ushered in a curiosity 0020.saggi.qxd 129 0020.saggi.qxd 130 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 130 13. Leandro Da Ponte, detto Bassano, Novembre, Vienna Kunsthistorisches Museum. Leandro Da Ponte, known as Bassano, November, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 131 process of centralisation, fusion and reorganisation of the imperial collections in the capital, a process that was coherently carried through by his daughter Marie-Thérèse with the opening to the public of the imperial galleries in the Belvedere in 1781. In this spirit, and on many occasions over the years, it was from Prague that many paintings deemed worthy of enriching and completing the Viennese collection were made to converge; to help make up for this relentless haemorrhaging, works then considered less important were sent back to Prague so that the residence would not be completely devoid of art work. In this context, the Months, obviously not much admired in the baroque leanings of Charles vi’s court, were sent to Prague in 1732 along with another 32 paintings. Y The same process continued through the following century, and came to an end in 1894 when the last shipment of paintings arrived from Prague at the Kunsthistorisches Museum on the Burgring, which had been inaugurated in 1891. This last shipment from Prague contained a whole 32 paintings by, or attributed to, the Bassanos – i.e. a third of the current collection. Amongst these were 9 canvases of the Months whose place within the cycle hadn’t been recognised, perhaps because the astrological signs had been repainted. The fact they weren’t recognised as belonging to the cycle is certainly why three paintings, in different rooms of the castle and therefore not included in the inspection, remained in Prague. Y This was the last of the voyages for the Bassano Months: they left Venice at the close of the 16th century, and adorned the Gallery in Prague for about 20 years. Escaping wars and marauders, they ended up, perhaps forgotten, in Neustadt, whence Leopold Wilhelm had them brought back to Vienna’s Stallburg. When Charles vi wanted the gallery refurbished according to baroque tastes, the paintings returned to Prague, there original destination, once more, whence they definitively returned in the late 19th century. As their history demonstrates, the Months were certainly appreciated by Rudolf ii and Leopold Wilhelm, two of Austria’s greatest collectors. On the basis of the transfers that I have attempted to reconstruct, they bear witness to the choices made by the great Habsburg collectors who succeeded in consigning to us one of the most extraordinary and complete collections in the world. curiosity 0020.saggi.qxd 131 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 132 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 133 vicende di note (e di gonnelle) tra le due capitali nello stesso anno, il 1787, due don giovanni: ma quanto diversi tra loro Sandro Cappelletto 1. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, dettaglio di un ritratto incompiuto eseguito dal cognato Joseph Lange verso il 1789: secondo la moglie Constanze era quello che gli rendeva più giustizia. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, detail of an unfinished portrait by his brotherin-law Joseph Lange, 1789 circa: according to his wife Constanze, it was the most accurate portrait. Y Venezia, 5 febbraio 1787. Al Teatro Giustinian di San Moisé, uno dei tanti luoghi di spettacolo scomparsi dal panorama della città, debutta Don Giovanni o sia il Convitato di pietra, “dramma giocoso” in un atto. Musica del veronese Giuseppe Gazzaniga (fig. 2), parole di Giovanni Bertati. Vienna, 1 ottobre 1787, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (fig. 1), assieme alla moglie Costanze, lascia la città dove risiede ormai da sei anni e inizia il viaggio verso Praga. Porta con sé il libretto, concluso, e la partitura, ancora incompleta, di un “dramma giocoso” scritto per lui da Lorenzo Da Ponte, con il quale la collaborazione era iniziata l’anno prima, a Vienna, in occasione delle Nozze di Figaro (fig. 3). E il 28 ottobre, al Nationaltheater di Praga, la nuova opera va in scena; l’argomento è identico: Il dissoluto punito o sia il Don Giovanni (fig. 4). Venezia-Vienna, un itinerario musicale consueto nel secondo Settecento. Un percorso di andata e ritorno, di idee e di persone, dove il dare e l’avere formano un equilibrio sempre mobile, vivo. Nel prevalere di una lingua, quella particolare lingua costituita dall’italiano dei libretti d’opera, che ormai da un secolo è diventata la lingua internazionale del melodramma. Si canta italiano da Pietroburgo a Lisbona, ma anche da Palermo a Torino, prefigurando un’identità nazionale ancora tutta da venire. E quei due “don Giovanni” di Venezia e Vienna non solo parleranno la stessa lingua, ma pronunceranno quasi le stesse parole. Y Tre dei quattro creatori delle due opere – e la seconda è un plagio, un generoso imprestito, o piuttosto una geniale riscrittura? – sono o sono stati ospiti abituali di Venezia e del suo sistema teatrale. E sono veneti, che in momenti diversi della loro vicenda professionale vivono a lungo a Vienna. Il quarto, Mozart, in laguna è venuto una sola volta, tra febbraio e marzo 1771, in tempo per vivere e affascinarsi degli ultimi giorni di Carnevale. Leopold e Wolfgang, padre e figlio, soggiornano a San Fantin, in un appartamento all’altezza del ponte dei Barcaroli o del Cuoridoro, che collega calle del Frutariol alla Frezzaria. Pochi passi da teatri impor- la musica 0020.saggi.qxd 133 vicende di note (e di gonnelle) tra le due capitali 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 2. Ignoto, Giuseppe Gazzaniga, Bologna, Museo internazionale e Biblioteca della Musica. Unknown, Giuseppe Gazzaniga, Bologna, Museo Internazionale e Biblioteca della Musica. 134 11:28 Pagina 134 tanti, come il San Benedetto e il San Moisè, dal Ridotto Nuovo (fig. 5) e dai suoi tavoli da gioco, dalla Fenice che ancora non c’è, dal San Samuele (fig. 6), dove nel 1655 ha esordito Goldoni. Sono ospiti di Johannes Wider, un conoscente del padre, che aveva un commercio di seta in Marzaria, e di sua moglie, la veneziana Venturina. Venturina mette al mondo diciannove figli; i sette maschi muoiono molto precocemente; delle figlie, ne sopravvivono sei: hanno dai ventotto ai cinque anni. Sei figlie e la madre, che non ha ancora cinquant’anni e accoglie il ragazzo con affetto, cordialità, bonomia di carattere. Quelle sette femmine, Mozart le chiama le «perle Wider». E in quelle quattro settimane veneziane scopre le maschere, il travestimento, la festa, il ballo. E l’erotismo, come conviene a un ragazzo che ha appena compiuto quindici anni. Y Da una lettera – più precisamente una postilla a una lettera inviata dal padre alla madre – alla sorella Nannerl rimasta a Salisburgo, sappiamo che Wolfgang scopre anche un gioco, un rituale, che lui dice essere tipicamente veneziano: gli amici di Salisburgo devono presto venire in laguna «per farsi dare l’attacca, cioè farsi sbattere col culo per terra per diventare un vero veneziano; anche a me lo volevano fare, ci si sono messe tutte e sette (le “perle Wider”, n.d.r.) e però non sono state capaci di buttarmi giù». Quando Mozart quindicenne è a Venezia, Giuseppe Gazzaniga ha ventotto anni. È nato a Verona nel 1743, a Venezia è arrivato ragazzo, per studiare con Niccolò Porpora, e seguirlo quando il maestro ritorna a Napoli, altra capitale – allora – della produzione e del consumo di teatro musicale, altro consuetissimo orizzonte per i musicisti veneziani. E per il Teatro Nuovo di Napoli, Gazzaniga compone Il barone di Trocchia, il suo primo intermezzo. Da Napoli a Vienna, dove per il Teatro di Corte debutta nel genere dell’opera buffa con Il finto cieco, su libretto di Da Ponte. E da Vienna a Venezia, dove nel 1772 compone la sua prima opera seria: Ezio, su libretto di Pietro Metastasio, che da quasi mezzo secolo risiedeva a Vienna con l’incarico di “poeta cesareo” (figg. 7 e 8). Intermezzi, opere buffe e serie: versatilità, rapidità, prontezza ad aderire ai diversi generi teatrali allora prevalenti. Gazzaniga, non ancora trentenne, è già nel pieno di un’attività professionale che lo porta di teatro in teatro, da Milano, a Novara, a Reggio Emilia, di nuovo a Venezia, ancora a Vienna, a Monaco, a Dresda, finché, nel 1791, sceglie la Cattedrale di Crema, con l’incarico di maestro di cappella. E a Crema resta fino alla morte, nel 1818. Y Il libretto del Don Giovanni veneziano è di Giovanni Bertati. È 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 135 nato 42 anni prima a Martellago; ha studiato nel seminario di Treviso grazie al mecenatismo di Antonio Grimani; ha debuttato presto, scrivendo soprattutto opere buffe. Garbo, gusto per la vivacità delle rime, capacità di alternare il comico al patetico. Apprezzato da Baldassare Galuppi, Giovanni Paisiello, Antonio Salieri. Nel 1790, riceve l’incarico di “poeta cesareo”, appartenuto già al Metastasio, e scrive il libretto per Il matrimonio segreto di Domenico Cimarosa, che alla prima viennese riscuote così incredibile successo da essere, subito, interamente bissato. Un episodio unico. Da Vienna, Bertati ritorna a Venezia, rallentando una produzione di libretti che tocca, per restare a quelli conosciuti, circa settanta titoli; non viaggia più: trova un impiego all’Arsenale, come archivista della Marina, a quel punto non più veneziana, ma austriaca. Fa in tempo a vedere ascesa e caduta di Napoleone, non si avvicina troppo ai fuochi delle nuove passioni romantiche, muore ottantenne nel 1815. Y Emanuele da Conegliano (fig. 9) nasce a Ceneda – oggi Vittorio Veneto – il 10 marzo 1749. Di famiglia ebrea, diventa cattolico e assume il nome del vescovo di Ceneda, appunto Lorenzo Da Ponte, da cui viene battezzato. Studia al seminario di Portogruaro, dove riceve gli ordini minori; insegna retorica, scrive poesie, si trasferisce a Venezia, dove ammira soprattutto le imprese casanoviane. È costretto a lasciare la città, va a Treviso, è bandito per aver scritto L’uomo per natura libero, trattatello ispirato alle nuove idee di Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Ancora Venezia, poi Gorizia, Dresda, dove inizia a frequentare gli ambienti teatrali e musicali; poi Vienna, dove arriva nel 1781: in quello stesso anno anche Mozart decide di lasciare Salisburgo, la sua città, e la corte dell’arcivescovo che fino ad allora, e senza scialare, gli aveva dato uno stipendio, e di tentare la fortuna come libero compositore. Y Dall’imperatore Giuseppe ii, affascinato dalla sua intraprendenza e versatilità, Da Ponte ottiene l’incarico di “poeta dei teatri imperiali” e scrive il primo di una serie di libretti: è Il ricco di un giorno, per la musica di Antonio Salieri, anch’egli veneto, nato a Legnago nel 1750 e allora massima autorità musicale viennese (fig. la musica 0020.saggi.qxd 135 vicende di note (e di gonnelle) tra le due capitali 0020.saggi.qxd 136 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 136 10). Poi, dopo i tre libretti creati per Mozart – Le nozze di Figaro, Don Giovanni, Così fan tutte – e la morte del suo imperiale protettore, ancora traslochi, sempre emigrante e sempre intraprendente. Trieste, Londra, infine New York: librettista, droghiere, grossista di medicinali, editore, libraio, insegnante di italiano, impresario. E a New York, nel 1825, fa rappresentare Don Giovanni: ovviamente il suo, il loro. Nel 1833, inaugura un nuovo teatro d’opera con La gazza ladra di Rossini (fig. 11). Muore a ottantanove anni, nel 1838, lasciando molti rimpianti. Y Lorenzo Da Ponte conosceva bene sia Gazzaniga che Bertati. Per il musicista aveva scritto, a Vienna, il libretto de Il finto cieco. Lo definisce «compositore di qualche merito, ma d’uno stile non più moderno», e così racconta il loro primo incontro professionale: «Per isbrigarmi presto scelsi una commedia francese, intitolata L’aveugle clairvoyant, e ne schiccherai un dramma in pochi giorni, che piacque poco, tanto per le parole che per la musica. Una passioncella per una donna di cinquant’anni, che disturbava la mente di quel brav’uomo, gli impedì di finire l’opera al tempo fissatogli». Cinquant’anni devono certo sembrare troppi al librettista, che nell’aria del catalogo cantata da Leporello, decide che «passion predominante» del suo cavaliere libertino è la «giovin principiante». Passione condivisa dall’autore, se si leggono le sue Memorie, narrate in prima persona e in una prospettiva che sempre lo propone come il deus ex machina della vita musicale europea di quegli anni. Tutto ruota intorno a lui, tutto nasce dalle sue idee e relazioni, dal suo talento. La vanità non gli faceva difetto, come l’estro. Y E, naturalmente, Da Ponte sostiene di essere stato lui l’ispiratore di Mozart: di aver scelto lui l’argomento e di averlo sviluppato con piena libertà, prendendo così le distanze dal libretto di Bertati, come per preventiva autodifesa da ogni eventuale accusa di plagio. Dopo i rispettivi Don Giovanni, i due si incontrano di nuovo a Vienna (fig. 12), dove Da Ponte era tornato per un soggiorno di qualche settimana, provenendo da Trieste. Bertati ha assunto la carica di “poeta cesareo”, mentre Da Ponte non ha più nessuna posizione ufficiale ed è in cerca di nuove commissioni. E così scrive del collega: «Io conosceva le sue opere, ma non lui. Egli n’aveva scritto un numero infinito, e, a forza di scriverne, aveva imparato un poco l’arte di produr l’effetto teatrale. Ma, per sua disgrazia, non era nato poeta e non sapeva l’italiano. Per conseguenza l’opere sue si potevano piuttosto soffrir 22-07-2009 3. Locandina della prima de Le nozze di Figaro al Burgtheater di Vienna, 1 maggio 1786. Placard for the premiere of Le nozze di Figaro at the Burgtheater, Vienna, May 1, 1786. 11:28 Pagina 137 sulla scena che leggerle». Poi, continua: «Dopo essere stato altri dieci minuti con lui e aver conosciuto per tutti i versi che il signor poeta Bertati altro non era che una bòtta gonfia di vento, mi congedai e andai a dirittura dal guardiano delle logge. Trovai con altrettanta sorpresa che compiacenza che i libretti di nove delle mie opere era tutti stati venduti». Da Ponte vende, Bertati no. Bertati è il poeta ufficiale della corte, l’abate Lorenzo sta sul mercato e non può essere tenero con i concorrenti. Avranno parlato anche dei loro simultanei Don Giovanni? Y Ma torniamo a quella sera del 5 febbraio 1787. Venezia non era dunque restata insensibile alla passione per le avventure di don Giovanni, una vicenda teatrale e musicale che attraversa l’Europa con la forza di un’onda incontenibile. È il 1630 quando, a Barcellona, il frate spagnolo Tirso de Molina pubblica, in veste anonima, la commedia El burlador de Sevilla y convidado de piedra. Per la prima volta assumono forma letteraria compiuta una vicenda, un mito narrativo, un personaggio che da tempo attraversavano la letteratura popolare, animando le rappresentazioni delle compagnie dei comici dell’arte. È il debutto letterario di don Juan Tenorio, libertino e cinico, che prova sommo piacere nel trasgredire ogni principio morale. Verrà punito, avvolto da fiamme infernali: l’empio non sfuggirà alla condanna eterna. Ma quanta vitalità, quanto spasso, prima dell’edificante morale conclusiva. Y L’intreccio dà vita a una serie infinita di figli, più o meno somiglianti al padre. È il destino dei miti, che affrontano qualsiasi metamorfosi senza mai snaturarsi. Su don Giovanni scrivono parole e musica, tra gli altri, Giacinto Andrea Cicognini, Jean-Baptiste Poquelin più noto come Molière, Thomas Corneille, Thomas Shadwell, Henry Purcell. Nel 1669, a Roma, a palazzo Colonna in Borgo, a due passi dalla basilica di San Pietro, dal cuore della cristianità, è il compositore Alessandro Melani, su libretto di Giovanni Filippo Apolloni, a rappresentare per la prima volta in Italia un “dramma musicale” liberamente ispirato alla commedia di Tirso de Molina. Nel 1734 la compagnia di comici dell’arte guidata da Eustachio Bambini mette in scena a Brno La pravità castigata; due anni do- la musica 0020.saggi.qxd 137 vicende di note (e di gonnelle) tra le due capitali 0020.saggi.qxd 138 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 138 po, il soggetto arriva in laguna, grazie al Don Giovanni Tenorio o il Dissoluto che Carlo Goldoni scrive per il Teatro Grimani. Nel 1761, a Vienna, Christoph Willibald Gluck, con la coreografia di Gaspare Angiolini, trasforma la commedia di Molière in un “balletto pantomima”: Don Juan ou Le festin de pierre. Nei due decenni successivi, le rappresentazioni si infittiscono ancora: Vincenzo Righini a Praga; Giacomo Tritto a Napoli; Gioacchino Albertini a Varsavia; Vincenzo Fabrizi a Roma. E quella sera del 5 febbraio 1787, mentre al San Moisè si alza il sipario sul “dramma giocoso” di Gazzaniga, al Teatro San Samuele, Francesco Gardi propone un “dramma tragicomico” ispirato, ma con lo spirito della farsa, al libretto di Bertati. Questa era Venezia: due prime la stessa sera, in due teatri diversi. Y L’intreccio, evidentemente, attrae. Anche perché un “vero” don Giovanni a Venezia aveva abitato e molto fatto parlare di sé. È la tesi, documentata e sorprendente, di Paolo Cattelan nel libro dedicato al periodo trascorso da Mozart a Venezia e poi Padova (Mozart. Un mese a Venezia, Venezia 2000). A metà Settecento, nel cuore della città, ha vissuto, peccato, ed è stata condannata una persona i cui tratti libertini si ritagliano bene sul personaggio di don Giovanni. È il Carnevale 1751, quando dà scandalo il caso del conte Francesco Falletti di Castelman, un piemontese nobile, così si presenta, che ha preso casa al ponte dei Barcaroli in rio San Fantin: vent’anni dopo soggiorneranno lì anche i Mozart. Il conte Francesco convive con “Rosa Romana”, al secolo Antonia Fontana. La coppia si prende e si lascia, litigiosa e complice. E molti sono gli eccessi di lui, come si apprende leggendo la decisione del Supremo Tribunale degli Inquisitori di Stato e degli Esecutori alla Bestemmia. Y «Blasfemo, libertino, celato sotto il manto di nobile condizione e carattere: impenitente e impunito “mai pensando a riforma di sorta [...] lontano dal timor di correzioni”», scrive Cattelan, citando il Tribunale veneziano. Che «de dì 7 gennaro 1751 M. V.» (More Veneto, corrispondente al 1752) lo mette al bando. «Francesco Falletti nativo Piemontese, detto anco conte di Castelman, solito abitar al Ponte dei Barcaroli in contrada di San Fantin, absente, ma legittimamente citato, imputato per quello, che oriundo di alieno stato, occultando la viltà della sua nascita, fosse anzi solito spacciarsi per Persona di carattere e nobile condizione; sostenendo per altro un contegno di vita reo, turpe, libertino e scandaloso. Correndo la di lui casa per un aperto postribolo, dando in essa ricetto continuo a più donne da Partito, approfittandosi da ritratti delle Medesme a suo sostentamento, 22-07-2009 4. Lorenzo Da Ponte, Il dissoluto punito o sia il Don Giovanni, frontespizio del libretto, Praga 1787, Vienna, Bibliothek der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde. Lorenzo Da Ponte, Il dissoluto punito o sia il Don Giovanni, frontispiece to the libretto, Prague, 1787, Vienna, Bibliothek der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde. 11:28 Pagina 139 senza riserve alcune di impiegarsi a loro fortuna, di commettere laidezze e disonestà, anco a pubblica vista [...] alieno dal contrassegnare qualunque professione e esercizio di Cristiana Cattolica Religione [...]. Sia e si intenda bandito da questa città di Venezia, e Dogado, e da tutte le altre città e venendo preso e ricondotto in questa città ed all’ora solita fra le due colonne di San Marco, sopra un palco d’eminenti forche sia per il ministro di Giustizia impiccato per le canne della gola sicché muoia». Y Bandito il falso conte Falletti, come verrà condannato alla detenzione perpetua nel manicomio di Charenton il vero marchese de Sade: inevitabile, dopo aver letto questa sentenza, pensare a Justine, o le disavventure della virtù, a Le 120 giornate di Sodoma. Ambedue i Gentiluomini prediligevano «commettere laidezze e disonestà» con le «donne da Partito», le ragazzine. E, sulle scene d’Europa, in quegli anni mille volte muore don Giovanni, appassionato di adolescenti e giovani donne sposate, irridente a ogni principio di «Cristiana Cattolica Religione», a ogni vincolo di affetti e familiare. Chissà se in quel mese veneziano, alle orecchie del giovane Wolfgang, magari raccontati dalle «sette perle» che lo circondavano, saranno arrivati echi, imprese e prodigi del «conte di Castelman», un ex vicino di casa. E come escludere che ne abbia sentito parlare Da Ponte, quando, poco più di due anni dopo la presenza veneziana dei Mozart, arriva anche lui in laguna, da dove sarà presto bandito per aver commesso adulterio, mettendo al mondo tre figli? Dalla vita di Falletti al libretto di Da Ponte e da quelle parole alla musica di Mozart? Y L’aspetto demoniaco è certo presente nella partitura mozartiana: dagli accordi iniziali dell’ouverture, alla forza altera con cui il protagonista, dopo aver superato lo smarrimento, perfino il tremore suscitato dall’inattesa apparizione della statua del Commendatore («Non l’avrei giammai creduto / ma farò quel che potrò») ritorna baldanzoso padrone di sé: «Leporello un’altra cena fa che subito si porti». Comunque splendido paron de casa. Ed è questo sguardo all’abisso, questo splendore della dissolutezza, questo incalzare dell’eccesso che segna la differenza netta tra i nostri due Don Giovanni. Non sono poche le metamorfosi che i personaggi conoscono nelle stesure di Bertati e Da Ponte. Don Giovanni (fig. 13), donna Elvira (fig. 14), donna Anna (fig. 15) e il suo promesso, il duca Ottavio, non cambiano nome. E simile rimane la loro funzione drammaturgica: due donne sfidate, lasciate, diversamente tradite dal libertino e l’incerto, troppo amoroso, poco propositivo, ancor meno seduttivo, spasimante di la musica 0020.saggi.qxd 139 vicende di note (e di gonnelle) tra le due capitali 0020.saggi.qxd 140 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 140 donna Anna. Biagio e Maturina sono ribattezzati, nella versione Da Ponte, Masetto e Zerlina: non è differenza da poco, se la coppia contadina appare così più giovane, ardente, desiderabile. Biagio va adagio, non Masetto. Y Bertati introduce un quarto personaggio femminile, la nobile donna Ximena, evidente richiamo all’originale ambientazione spagnola; Da Ponte lo elimina. Pasquariello diventa Leporello, mantenendo il ruolo del servo (fig. 16). Scompare il ruolo di Lanterna, cameriere di don Giovanni. Cambiano i nomi, il numero dei personaggi diminuisce. Ma soprattutto si trasformano il lessico, il senso, la forza dei versi. Così racconta Pasquariello nell’aria del catalogo: Dell’Italia, ed Alemagna Ve n’ho scritte cento, e tante. Della Francia, e della Spagna Ve ne sono non so quante: Fra madame, cittadine, Cameriere, cuoche e sguattere; Perché basta che sian femmine Per doverle amoreggiar. Vi dirò ch’è un uomo tale, Se attendesse alle promesse, Che il marito universale Un dì avrebbe a diventar. Vi dirò ch’egli ama tutte Che sian belle, che sian brutte: Delle vecchie solamente Non si sente ad infiammar. E così invece Leporello: Madamina, il catalogo è questo Delle belle che amò il padron mio; Un catalogo egli è che ho fatt’io; Osservate, leggete con me. In Italia seicento e quaranta; In Almagna duecento e trentuna; Cento in Francia, in Turchia novantuna; Ma in Ispagna son già mille e tre. V’han fra queste contadine, Cameriere, cittadine, V’han contesse, baronesse, Marchesine, principesse. E v’han donne d’ogni grado, D’ogni forma, d’ogni età. Nella bionda egli ha l’usanza Di lodar la gentilezza, Nella bruna la costanza, Nella bianca la dolcezza. Vuol d’inverno la grassotta, Vuol d’estate la magrotta; È la grande maestosa, La piccina e ognor vezzosa. Delle vecchie fa conquista Pel piacer di porle in lista; Sua passion predominante È la giovin principiante. Non si picca - se sia ricca, Se sia brutta, se sia bella; Purché porti la gonnella, Voi sapete quel che fa. Y L’invenzione dei numeri, la dilatazione della sequenza dei luoghi, delle età, delle immagini, delle perversioni, l’infittirsi dei richiami metrici, delle rime. Un elenco, nient’altro che un elenco, ma quanto più incalzante – e disperante per donna Elvira che lo ascolta – quello creato da Da Ponte. La festa paesana che accompagna il matrimonio tra Biagio e Maturina è interrotta dall’ingresso di Pasquariello e don Giovanni, subito attratto dalle bellezze della contadina. Per corteggiarla, deve liquidare Biagio: lo prende a schiaffi, lo minaccia e lui, privo di diritti, non 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 141 la musica 0020.saggi.qxd 5. Francesco Guardi, Il Ridotto Nuovo in San Moisè a Venezia, Venezia, Museo del Settecento veneziano, Ca’ Rezzonico. Francesco Guardi, The Ridotto Nuovo Theatre, San Moisè, Venice, Venice, Museo del Settecento Veneziano, Ca’ Rezzonico. può che imprecare alla propria condizione e maledire il tradimento di lei. A me schiaffi sul mio viso! A me far un tal affronto!... (a Maturina) Ma gli schiaffi non li conto, Quanto conto, fraschettaccia, Che tu stai con quella faccia, A vedermi maltrattar. (a Don Giovanni) Ma aspettate. Ma lasciate. Ch’io mi possa almen sfogar. Da tua madre, da tua zia, Da tua nonna adesso io vado, Vo’ da tutto il parentado La faccenda a raccontar. Y La medesima situazione è così vissuta da Masetto: Ho capito, signor sì! Chino il capo e me ne vo. Giacché piace a voi così, Altre repliche non fo. Cavalier voi siete già. Dubitar non posso affé; Me lo dice la bontà Che volete aver per me. (a Zerlina, a parte) Bricconaccia, malandrina! Fosti ognor la mia ruina! (a Leporello, che lo vuol condur seco) Vengo, vengo! (a Zerlina) Resta, resta. È una cosa molto onesta! Faccia il nostro cavaliere Cavaliera ancora te. Y Niente «fraschettacce», niente «nonne», e quanto più dolore nel constatare, da parte di Masetto, l’irrimediabilità della sua condizione di servo, impotente a fermare il progetto erotico del Don, perfino nel giorno delle sue nozze. Infine, l’incontro, l’ul- 141 vicende di note (e di gonnelle) tra le due capitali 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 142 timo, tra don Giovanni e il Commendatore, venuto a prenderlo, a dannarlo. Così Giovanni Bertati: Don Giovanni Siedi Commendator. Mai fin’ ad ora Credere non potei, che dal profondo Tornasser l’ombre ad apparir nel mondo. Se creduto l’avessi, Troveresti altra cena, Pure se di mangiar voglia ti senti, Y Così Da Ponte: La statua Don Giovanni, a cenar teco M’invitasti e son venuto! Don Giovanni Non l’avrei giammai creduto; Ma farò quel che potrò. Leporello, un’altra cena Fa che subito si porti! Leporello (facendo capolino di sotto alla tavola) Ah padron! Siam tutti morti. Don Giovanni (tirandolo fuori) Vanne dico! La statua (a Leporello che è in atto di parlare) Ferma un po’! Non si pasce di cibo mortale Chi si pasce di cibo celeste; Altre cure più gravi di queste, Altra brama quaggiù mi guidò! Leporello (La terzana d’avere mi sembra E le membra fermar più non so.) Don Giovanni Parla dunque! Che chiedi! Che vuoi? La statua Parlo; ascolta! Più tempo non ho! 142 Mangia; che quel che c’è t’offro di core; E teco mangerò senza timore. Commendatore Di vil cibo non si pasce Chi lasciò l’umana spoglia. A te guidami altra voglia, Ch’è diversa dal mangiar Don Giovanni Parla, parla, ascoltandoti sto. La statua Tu m’invitasti a cena, Il tuo dover or sai. Rispondimi: verrai Tu a cenar meco? Leporello (da lontano, sempre tremando) Oibò; Tempo non ha, scusate. Don Giovanni A torto di viltate Tacciato mai sarò. La statua Risolvi! Don Giovanni Ho già risolto! La statua Verrai? Leporello (a Don Giovanni) Dite di no! Don Giovanni Ho fermo il cuore in petto: Non ho timor: verrò! Y In questa scena, il don Giovanni “mozartdapontiano” deve essere grande quanto il momento richiede: se Leporello trema, lui si preoccupa di non venire accusato di «viltate». Ma le differenze non sono soltanto lessicali. «Pur coetaneo, il Don Giovanni di Da Ponte-Mozart sembra appartenere ad un’altra cultura musicale e letteraria», scrive Daniela Goldin Folena. Più tesa, inquieta, lontana dalle «regolari strofette, a ritmo altrettanto regolare, senza sorprese nella dinamica e con le prevedibili piccole melodie dell’omonima operina di Bertati-Gazzaniga». La diversità, infatti, 22-07-2009 6. Gabriele Bella, Il teatro di San Samuele, Venezia, Fondazione QueriniStampalia. Gabriele Bella, The San Samuele Theatre, Venice, Fondazione Querini-Stampalia. 11:28 Pagina 143 riguarda soprattutto la musica: «Certamente Gazzaniga non andò oltre alle limitazioni e al linguaggio dell’opera buffa», riflette Stephen Kunze, che al Don Giovanni veneziano ha dedicato un ampio studio. Ma la riflessione più esplicita sulle potenzialità del soggetto appartiene allo stesso Mozart, che così racconta la prima reazione all’idea: «Il mio cervello si infiamma, il soggetto si crea davanti a me tutto intero. Io non sento una dopo l’altra tutte le parti dell’orchestra, ma tutte insieme. Con quale gioia non posso esprimerlo». Y Anche la scelta della voce del protagonista è indicativa: il compositore veronese predilige la vocalità tenorile, non gli offre quella possibilità di scendere nel grave, nel cupo, nel torbido che non possiamo disgiungere dalla voce di basso del personaggio mozartiano. Gazzaniga non guarda in faccia il demoniaco: se ne tiene lontano, graziosamente. E il finale è scritto in forma di tarantella: scomparso don Giovanni, precipitato nelle fiamme infernali, tutti gli altri personaggi ballano e invitano a unirsi a loro. Nessuno si dichiara orfano degli eccessi perduti, e la musica non ne evoca l’assenza. «Uno stile non più moderno»: la sintesi di Da Ponte appare perfetta, ribadendo che ogni epoca ha la propria idea di modernità. Ma nello stesso tempo è evidente, anche dai tre momenti citati, che la fonte principale del suo testo è proprio Bertati. Da Ponte, in quei mesi del 1787, aveva molta fretta e un Don Giovanni già “schiccherato” gli tornava comodo: mentre lavorava per Mozart, stava infatti scrivendo altri due libretti, Axur, re di Ormuz per Antonio Salieri e L’arbore di Diana per Martin y Soler. E riuscì a soddisfare tutti e tre i clienti. Y A differenza del suo più celebre fratello minore (sia pure di soli otto mesi), il “dramma giocoso” di Bertati-Gazzaniga è anche un esplicito atto d’amore per la città che ne ospita la prima rappresentazione. In scena si brinda alla regalità dei patrizi veneziani: «Faccio un brindisi di gusto / a Venezia singolar. / Nei Signori il cor d’Augusto / si va proprio a ritrovar». Alla delizia delle femmine: «Alle donne veneziane / questo brindisi or presento, / che son piene di talento, / di bellezza e d’onestà. / Son tanto leggiadre / con quei zendaletti, / che solo a guardarle / vi muovon gli la musica 0020.saggi.qxd 143 vicende di note (e di gonnelle) tra le due capitali 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 7. Pietro Metastasio, poeta cesareo, incisione, Milano, Civica raccolta delle Stampe Achille Bertarelli. Pietr Metastasio, Caesarean poet, engraving, Milan, Civica Raccolta delle Stampe Achille Bertarelli. 144 11:28 Pagina 144 affetti». I nobili, le donne, la città tutta: «Far devi un brindisi alla città, / che noi viaggiando di qua e di là, / abbiam trovato ch’è la miglior». E la musica accompagna questo laico inno alla dolce vita veneziana con quella galanteria cortese che ritroviamo in certi sguardi, in certi interni di Pietro Longhi, con l’aura festosa che anima il gran passaggio sul Canalazzo nei dipinti, nei colori di Canaletto. Le passioni di don Giovanni sono più ardenti e spietate; troppo, per avere diritto di cittadinanza in qualunque società urbana. Se a Venezia, i veri conti Falletti si mandavano alla forca, «sicché muoia» e il Don Giovanni di Gazzaniga e Bertati finisce in un rassicurante brindisi, a Vienna – dove il “dramma giocoso” di Mozart e Da Ponte debutta al Burgtheater il 5 maggio 1788, con alcune modifiche dovute alle richieste dei cantanti e a nuove intuizioni degli autori – la ricezione non è favorevole. Y «È universalmente noto l’insuccesso cui Mozart andò incontro con queste opere presso il pubblico viennese; dopo le prime recite, il Don Giovanni non fu più eseguito per quattro anni», scrive Gernot Gruber in La fortuna di Mozart, il più documentato studio sulla ricezione della sua produzione, riferendosi al trittico composto sui libretti italiani di Lorenzo Da Ponte: Nozze di Figaro (1786), Don Giovanni (1787), Così fan tutte, che nel 1790 conclude la loro collaborazione. «Cucina troppo condita», «musica non per tutti i palati», «ha l’orecchio guasto»: sono questi i motivi ricorrenti delle critiche ai suoi lavori, soprattutto cameristici e operistici. Ai viennesi Mozart piace quando esegue le proprie musiche al pianoforte, quando improvvisa: «Non aveva rivali nel phantasieren», scrivono i contemporanei. Non quando pretende di andare oltre le convenzioni drammaturgiche ed espressive del tempo. Se perfino i musicisti di professione credono di vedere degli errori nelle più ardite invenzioni armoniche dei suoi quartetti, al pubblico dei teatri di corte piacciono poco gli esperimenti che quel librettista e quel compositore portano avanti, con la decisiva complicità e sostegno di Giuseppe ii. Y Era stato l’imperatore a permettere l’allestimento dell’opera tratta da Le mariage de Figaro, l’eversiva commedia di Beaumarchais, che la censura austriaca aveva invece impedito di rappresentare a teatro in lingua tedesca. Lui aveva agevolato la prima viennese del Don Giovanni dopo il successo di Praga; lui stesso stimolerà la nascita dell’intreccio, allora giudicato scandaloso, di Così fan tutte, dove due coppie di giovani amanti si tradiscono e si perdonano, senza drammi, governati nei loro girotondi sentimentali dal timone di un filosofo cinico, don Alfonso, per il quale fedeltà, doveri coniugali, sacralità della famiglia 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 145 sono gusci vuoti. Tre opere arditissime, per i tempi. Come interpretare il protagonismo anche intellettuale del servo Figaro, tanto più inventivo e accattivante rispetto al personaggio del conte, ancora contraddittorio verso il feudale ius primae noctis, da lui abolito però con mille ripensamenti, e ossessionato da Susanna, promessa di Figaro e bella cameriera della contessa, moglie molto tradita? Y E mentre gli ambasciatori a Parigi iniziano a inviare preoccupati dispacci sulla temperatura politica francese, doveva risuonare inaccettabile quell’invito che l’aristocratico don Giovanni, prima da solo e a piena voce, poi assieme al coro dei contadini, solennemente, rivolge alle tre maschere che chiedono di essere ammesse alla festa nel suo palazzo: «È aperto a tutti quanti – Viva la libertà». «Mozart ha realizzato quanto gli imponeva lo spirito demoniaco del proprio genio, dal quale era posseduto», scrive Goethe a proposito di Don Giovanni, intuendone perfettamente le tinte nere e preromantiche. Se a Praga la borghesia applaude a tali arditezze, come può la “classica” e devota nobiltà viennese accogliere, approvare argomenti così scabrosi? La morte di Giuseppe ii, ne1 1790, significa per Mozart l’inizio del periodo più disperato della propria esistenza privata e professionale; scomparso il suo illuminato protettore, si risolleverà soltanto negli ultimi mesi di vita, in quel 1791 segnato da una incredibile pulsione creativa. Ma allora, per restare alle opere, altri saranno i soggetti: La clemenza di Tito, dedicata all’incoronazione di Leopoldo ii a re di Boemia, e Il flauto magico: un titolo “istituzionale” in italiano e una favola filosofica destinata al più popolare teatro e pubblico di Vienna. Due successi, alla fine di un percorso artistico verso il quale la capitale dell’impero aveva manifestato brevi entusiasmi e assai più lunghi periodi di disinteresse, quando non di distacco. la musica 0020.saggi.qxd 145 0020.saggi.qxd 146 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 146 8. Jacopo Amigoni, Ritratto di gruppo, Melbourne, National Gallery of Victoria; il primo a sinistra è Pietro Metastasio, al centro il celebre castrato Carlo Broschi detto Farinelli. Jacopo Amigoni, Portrait group: The singer Farinelli and friends, Melbourne, National Gallery of Victoria. The first on the left is Metastasio; in the middle, beside Teresa Castellini is the famous castrato Farinelli. 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 147 on notes (and skirts) between the two capitals two don giovannis in the same year, but so very different music 0020.saggi.qxd Sandro Cappelletto Y Venice, February 5, 1787. Don Giovanni o sia il Convitato di pietra (literally, Don Giovanni or The Stone Guest) debuted at the Giustinian theatre at San Moisè, one of the many theatres in Venice to have subsequently disappeared. The libretto was by Giovanni Bertati, and the music by Giuseppe Gazzaniga (fig. 2), from Verona. Vienna, October 1, 1787. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (fig. 1), along with his wife Costanze, left the city where he had been residing for six years and set off for Prague. He took with him the finished libretto and the as-yet unfinished score for a “playful drama” written for him by Lorenzo Da Ponte, with whom he had started collaborating with The Marriage of Figaro (fig. 3) the year before in Vienna. This new opera went on stage at the Nationaltheater in Prague on October 28, with exactly the same theme: Il dissoluto punito o sia il Don Giovanni (fig. 4, literally The Rake Punished, or Don Giovanni). Venice-Vienna, a rather commonplace musical itinerary in the second half of the 18th century. A two-way journey, of ideas and people, where giving and receiving formed a mobile, living equilibrium. And one language prevailed above all others: Italian, used for opera for a century already, was the international language used for melodrama. Italian was used for singing from St Petersburg to Lisbon, but also from Palermo to Turin, prefiguring a national identity that had yet to become concrete reality. And those two Don Giovannis, one in Venice and the other in Vienna, not only speak the same language, but have almost the same words. Y Three of the four creators of the two operas – and is the second plagiarism, a generous borrowing, or a very clever rewriting? – were or had been habitual guests in Venice and its theatrical system. And they were from the Veneto, and in different periods in their professional life they spent quite some time in Vienna. The fourth, Mozart, had come to Venice only once, in February and March 1771, just in time to be fascinated by the closing days of the Carnival. Leopold and Wolfgang, father and son, stayed at San Fantin, in an apartment near the Ponte dei Barcaroli or del 147 on notes (and skirts) between the two capitals 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 9. Nathaniel Rogers, Ritratto di Lorenzo Da Ponte, Vittorio Veneto, Museo del Cenedese. Nathaniel Rogers, Portrait of Lorenzo Da Ponte, Vittorio Veneto, Museo del Cenedese. 148 11:28 Pagina 148 Cuoridoro, which links Calle del Frutariol and the Frezzaria. In other words, they were a stone’s throw from important theatres like the San Benedetto, the San Moisè, the Ridotto Nuovo (fig. 5) with its gambling facilities, the Fenice (which had yet to be built) and the San Samuele (fig. 6), where Goldoni debuted in 1655. They were the guests of Johannes Wider (one of Mozart’s father’s acquaintances, who had a silk shop in Marzaria) and his Venetian wife, Venturina. Venturina had 19 children in all – all seven boys had died early, and the surviving six girls were aged between 28 and 5. The six girls and the mother (who had not turned fifty yet) welcomed the young Mozart with affection, cordiality and affability. Mozart called these seven women the “Wider pearls”. In that four-week stay in Venice, he discovered masks, transvestism, feasts and balls. Not to mention eroticism, which would be rather unsurprising for a boy who has just turned fifteen. Y From a letter (or, more precisely, from a post script to a letter his father sent to his mother) to his sister Nannerl, who had remained in Salzburg, we know that Wolfgang also discovered a game, a ritual, that he says is typically Venetian: his Salzburg friends have to come to Venice “to play attacca, i.e. be forced to fall flat on your bum, if you want to be a real Venetian; all seven [of the Wider pearls] tried, but they couldn’t do it”. When the 15-year-old Mozart was in Venice, Giuseppe Gazzaniga was twenty-eight. He was born in Verona in 1743, and came to Venice when he was very young to study under Niccolò Porpora. He followed him when the maestro returned to Naples, which at that time was another capital of musical production and consumption, another habitual port of call for Venetian musicians. For Naples’ Teatro Nuovo, Gazzaniga composed Il barone di Trocchia, his first intermezzo. From Naples to Vienna, where he debuted in the opera buffa genre with his Il finto cieco (libretto by Da Ponte) for the court theatre. And from Vienna he returned to Venice, where, in 1772, he composed his first serious opera, Ezio, with a libretto by Pietro Metastasio, who had been living in Vienna for almost 50 years as “Caesarean poet” (figs. 7, 8). Intermezzos, opera buffa and serious works: versatility, speed and readiness to conform to the different theatrical genres that were prevalent at the time. Gazzaniga, who had not yet turned 30, was already in the full swing of his professional activity, which would take him from theatre to theatre – Milan, Novara, Reggio Emilia, Venice once more, Vienna yet again, Munich and Dresden until, in 1791, he opted for the cathedral in Crema, where he was chapel 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 149 master. And he stayed in Crema until his death in 1818. The libretto for the Venetian Don Giovanni was by Giovanni Bertati. He was born 42 years earlier in Martellago, then studied at the Treviso seminary thanks to Antonio Grimani’s patronage. He made his debut while still young, and wrote opere buffe above all. Graceful, with a taste for the vivacity of rhyme and an ability to alternate comedy and pathos. Appreciated by Baldassare Galuppi, Giovanni Paisiello, Antonio Salieri. In 1790, he was nominated “Caesarean poet” (as had Metastasio before him) and wrote the libretto for Domenico Cimarosa’s Il matrimonio segreto, which was such a triumphal success on opening night in Vienna that it was encored from beginning to end. Something that would never happen again. Bertati then returned to Venice, writing fewer libretti (though he would eventually tally about 70 that we know of) and no longer travelling. He found a job at the Arsenale as an archivist for the Navy, which at that time was no longer Venetian but Austrian. He managed to see the rise and fall of Napoleon, was barely moved by new Romantic passions, and died in 1815 at the age of 80. Y Emanuele da Conegliano (fig. 9) was born in Ceneda (now Vittorio Veneto) on March 10, 1749. Born to a Jewish family, he converted to Catholicism and took the name of the bishop of Ceneda (Lorenzo Da Ponte) on being baptised. He studied at the Portogruaro seminary, where he received his minor orders. He taught rhetoric, wrote poetry and moved to Venice, where he above all admired Casanova’s feats. He was forced to leave the city, went to Treviso, whence he was banished for having written L’uomo per natura libero (lit. tr. “Man is free by nature”), a little tract inspired by the new ideas of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. He returned to Venice, then moved to Gorizia and Dresden, where he began to frequent theatrical and musical circles. He then moved to Vienna in 1781, the same year Mozart decided to leave Salzburg, his native city, and the court of the archbishop who had up to then paid his very generous stipend, to try his luck as a freelance composer. Y The emperor Joseph ii, fascinated by his enterprise and versatility, nominated Da Ponte “poet of the imperial theatres”, after which Da Ponte wrote the first of a series of libretti – Il ricco di un giorno, with music by Antonio Salieri, who was also from the Vene- music 0020.saggi.qxd 149 on notes (and skirts) between the two capitals 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 10. Antonio Salieri, Kappellmeister di corte a Vienna, in un ritratto anonimo. Antonio Salieri, Court Kappellmeister in Vienna, an anonymous portrait. 11. Vincenzo Camuccini, Ritratto di Gioachino Rossini, Milano, Museo teatrale alla Scala. Vincenzo Camuccini, Portrait of Gioachino Rossini, Milan, Museo Teatrate alla Scala. 150 11:28 Pagina 150 to (b. Legnago, 1750) and was considered the greatest musical authority in Vienna (fig. 10). Then, after the three libretti written for Mozart (Le nozze di Figaro, Dion Giovanni and Così fan tutte) and the death of his imperial protector, there were more moves, further migrations and even greater enterprise. Trieste, London, and finally New York: libretto writer, grocer, wholesaler of medicinal products, Italian teacher and impresario. And he had Don Giovanni performed in New York in 1825 – obviously his own, their own version. In 1833, he inaugurated a new opera theatre with a performance of Rossini’s La gazza ladra (fig. 11). He died at the age of 89, in 1838, leaving behind many regrets. Y Da Ponte knew Gazzaniga and Bertati very well. In Vienna, he had written the libretto for Il finto cieco for the musician. He defined him a “composer of some merit, but a style that is no longer modern”, and had the following to say about their first professional meeting: “To speed things up I chose a French comedy entitled L’aveugle clairvoyant, and I fashioned a drama in a few days, which was much liked, both for the words and the music. A little passion for a 50-year-old woman, which disturbed the mind of that good man, stopped him from finishing the opera by the established deadline”. Fifty must certainly have seemed too old for the librettist, who in the Leporello aria decides that the “predominant passion” of his libertine knight is the “young ingenue”. A passion shared by the author if we are to believe his Memorie, written in the first person and point of view that seems to promote himself as the deus ex machina of the European musical world of the times. Everything revolved around him, everything came about because of his ideas and relations, and his talent. He was as vain as he was inspired. Y And naturally Da Ponte maintained that he had inspired Mozart, that he had chosen the theme and developed it in full freedom, thus moving away from Bertati’s libretto – a sort of a priori self-defence, should anyone accuse him of plagiarism. After their respective Don Giovannis, the two met again in Vienna (fig. 12), where Da Ponte had returned, coming from Trieste, for a short stay of a few weeks. Bertati accepted the position of “Caesarean poet”, while Da Ponte no longer had an official position and was looking for new commissions. This is what he wrote to a colleague: “I knew his operas, but not him. He had written an infinite number of operas and, having written so many, had somewhat learned the art of producing theatrical effect. But, alas!, he was not born a poet nor did he know Italian. Consequently, his operas could be 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 151 suffered on stage but not read...” He then goes on: “After having spent another ten minutes with him and thoroughly understood that the lord poet Bertati is nothing other than a hot-air balloon, I took my leave and went straight to the caretaker of the loggias. I was as surprised as pleased to see that the libretti for nine of my operas had all been sold...” Da Ponte sold, Bertati didn’t. Bertati was official court poet, while the abbot Lorenzo is part of the market and can not be nice about his competitors. Might they also have spoken about their respective Don Giovannis? Y But let’s go back to the evening of February 5, 1787. Venice had remained indifferent, therefore, to Don Giovanni’s passions for adventure, a theatrical and musical event that swept through Europe like a violent wave. It was 1630 when, in Barcelona, the Spanish monk Tirso de Molina anonymously published the play El burlador de Sevilla y convidado de piedra. For the first time the narrative myth and character that had for a long time been part of popular literature coalesced into a fully-fledged literary form that animated the performances of the commedia dell’arte performers. It was the official literary debut of Don Juan Tenorio, a libertine and cynic, who derives great pleasure from breaking every moral principal. He will be punished, obviously, engulfed in infernal flame: the wicked can never escape eternal condemnation. But what vitality, what enjoyment, before the edifying moral conclusion! Y The plot was to engender an infinite number of children, all more or less similar to their father. Such is the destiny of myths – they are forced to deal with all sorts of metamorphoses without ever losing their nature. Musical and literary authors who worked on Don Giovanni included Giacinto Andrea Cicognini, Jean-Baptiste Poquelin better known as Molière, Thomas Corneille, Thomas Shadwell and Hen- music 0020.saggi.qxd 151 on notes (and skirts) between the two capitals 0020.saggi.qxd 152 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 152 ry Purcell. In 1669, at Palazzo Colonna in Borgo in Rome, a stone’s throw from St Peter’s, the heart of Christianity, it was the composer Alessandro Melani, with a libretto by Giovanni Filippo Apolloni, who put on a “musical drama” loosely based on Tirso de Molina’s play, the first of its kind in Italy. In 1734, a commedia dell’arte company under the leadership of Eustachio Bambini staged La pravità castigata in Brno; two years later, the subject arrived in Venice in the form of Don Giovanni Tenorio o il Dissoluto, written by Goldoni for the Teatro Grimani. In 1761, in Vienna, Christoph Willibald Gluck, with choreography by Gaspare Angiolini, transformed Molière’s play into a “pantomime ballet”: Don Juan ou Le festin de pierre. There were even more performances in the following two years: Vincenzo Righini in Prague; Giacomo Tritto in Naples; Gioacchino Albertini in Warsaw; Vincenzo Fabrizi in Rome. And on the evening of February 5, 1787, as the curtain went up on Gazzaniga’s “playful drama” at San Moisè, Francesco Gardi was putting on a “tragicomic drama” at the San Samuele theatre, a play inspired by Bertati’s libretto, though imbued with a sense of farce. This was Venice: two premieres on the same night, at two different theatres. Y The story, obviously, was a favourite. And a possible explanation is that there had been a real Don Giovanni in Venice, and he had made many a tongue wag. Or at least this is a well-documented hypothesis put forward by Paolo Cattelan in his book on the period Mozart spent in Venice and Padua (Mozart – un mese a Venezia, Venice 2000). In the mid 18th century, in the heart of the city, a person whose libertinage fits perfectly with the character of Don Giovanni actually lived, sinned and was condemned in Venice. During the Carnival of 1751, there was the scandalous case of Francesco Falletti di Castelman, a count from Piedmont (or so he introduced himself) who rented a house at the Ponte dei Barcaroli in Rio San Fantin (the same house Mozart would stay in 20 years later). The count lived with “Rosa Romana”, whose real name was Antonia Fontana. They were constantly bickering and making up again. He was given to excess, as is clear in the sentence of the Supreme Tribunal of the State Inquisitors and Punishers of Blasphemy. Y “Blasphemous, a libertine, hidden beneath the cloak of noble condition and character: impenitent and unpunished, he has never thought of reforming himself in any way... far from fearing correction”, writes Cattelan, citing the Venetian tribunal. On January 7, 1751 MV (“More Veneto”, which corresponds to 1752), the same tribunal banished the count. “Francesco Falletti, a native of Pied- 22-07-2009 12. Carl Schütz, La cattedrale di Santo Stefano a Vienna, in un’incisione del 1792: Mozart vi si sposò e, a dicembre 1791, vi ebbe il funerale. Carl Schütz, St Stephen’s Cathedral, Vienna, in an engraving of 1792. This is the cathedral Mozart was married in, and where his funeral was held in December, 1791. 11:28 Pagina 153 mont, also known as Count di Castelman, usually resident at the Ponte dei Barcaroli in Contrada di San Fantin, absent, but legitimately cited, charged with, coming from an alien state, hiding the baseness of his birth, and would in fact fob himself off as Person of character and noble condition; and leading, what is more, an obscene, libertine and contemptible life. Running his home as an open brothel, continually putting up there within several Eligible women, making use of portraits of these Same women for his sustenance, without any reservations whatsoever in making use of their fortune, in committing all sort of foul offence and dishonesty, even in public view... without manifesting any profession or exercise of the Catholic Christian Religion... May he be banished from this city of Venice, and its Dogado, and from all other cities; should he be caught there within, he shall be led back in to the city and at the usual hour between the two columns of St Mark, upon a firm gallows, he shall by the Minister of Justice be hanged by the neck until he be dead”. Y The fake count was to be put to death, just as the real Marquis de Sad was detained in the Charenton asylum: our mind automatically goes from the “count” to Justine or The 120 Days of Sodom. Both Gentlemen enjoyed “committing all sort of foul offence and dishonesty” with “Eligible women”, i.e. young girls. On the stages of Europe in those years, thousands of Don Giovannis were put to death for their passion for adolescent girls and young married women, for their derision of the principles of the “Catholic Christian Religion” and the bonds of affection and family. Who knows if, during his sojourn in Venice, the young Mozart heard stories, perhaps from the lips of the “seven pearls”, about the feats and exploits of the “count di Castelman”, a “neighbour” to some music 0020.saggi.qxd 153 on notes (and skirts) between the two capitals 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 154 extent. And how can we exclude that Da Ponte heard the same stories when, little more than two years after Mozart’s stay in Venice, he also arrived in the city, from which he would soon be banned for having committed adultery and fathered three children? From the life of Falletti to the libretto by Da Ponte and from these words to the music of Mozart? Y The demonic aspect is certainly present in Mozart’s score: from the opening chords of the overture to the haughty force with which the protagonist, after having got over his confusion, or even his fear, at the unexpected sight of the statue of the Commendatore, regains supreme command of himself: “Leporello another dinner make that soon he be gone”. A nonetheless splendid host, or paron de casa. And it is this looking into the abyss, this splendorous dissolution, this relentless excess that marks the clear distinction between our two Don Giovannis. There are quite a few metamorphoses that the characters undergo in Bertati’s and Da Ponte’s works. Don Giovanni, Donna Elvira, Donna Anna (figs. 13, 14, 15) and her betrothed, Duke Ottavio, all have the same names. Just as their dramatic function is the same: two women who are challenged, abandoned and betrayed by the libertine, and Donna Anna’s uncertain, overly loving, inconsequential, and by no means seductive suitor. Biagio and Maturina have, in Da Ponte’s version, become Masetto and Zerlina: the difference is significant, and the rustic couple therefore appear younger, keener, more desirable. Biagio implies caution; Masetto most certainly does not. Y Bertati introduces a fourth female character, the noblewoman Donna Ximena, an obvious referencing of the original Spanish setting; Da Ponte does not. Pasquariello becomes Leporello, and maintains his role as servant (fig. 16). Lanterna, Don Giovanni’s chamber maid, disappears. Names are changed, and characters are dropped. But above all, it is the words, the meaning and the force of the poetry that is transformed. This is Pasquariello in the “Catalogue Aria”: Dell’Italia, ed Alemagna Ve n’ho scritte cento, e tante. Della Francia, e della Spagna Ve ne sono non so quante: Fra madame, cittadine, Cameriere, cuoche e sguattere; Perché basta che sian femmine Per doverle amoreggiar. 154 Vi dirò ch’è un uomo tale, Se attendesse alle promesse, Che il marito universale Un dì avrebbe a diventar. Vi dirò ch’egli ama tutte Che sian belle, che sian brutte: Delle vecchie solamente Non si sente ad infiammar. 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 155 And this is Leporello: Madamina, il catalogo è questo Delle belle che amò il padron mio; Un catalogo egli è che ho fatt’io; Osservate, leggete con me. In Italia seicento e quaranta; In Almagna duecento e trentuna; Cento in Francia, in Turchia novantuna; Ma in Ispagna son già mille e tre. V’han fra queste contadine, Cameriere, cittadine, V’han contesse, baronesse, Marchesine, principesse. E v’han donne d’ogni grado, D’ogni forma, d’ogni età. Nella bionda egli ha l’usanza Di lodar la gentilezza, Nella bruna la costanza, Nella bianca la dolcezza. Vuol d’inverno la grassotta, Vuol d’estate la magrotta; È la grande maestosa, La piccina e ognor vezzosa. Delle vecchie fa conquista Pel piacer di porle in lista; Sua passion predominante È la giovin principiante. Non si picca - se sia ricca, Se sia brutta, se sia bella; Purché porti la gonnella, Voi sapete quel che fa. music 0020.saggi.qxd Y The invention of the numbers, the dilating of the sequence of places, ages, images, perversions, the wealth of metrical echoes and rhymes. A list, nothing other than a list, but how much more pressing (and agonising for Donna Elvira as she listens) in the version created by Da Ponte. The country feast for the marriage of Biagio and Maturina is interrupted by the arrival of Pasquariello and Don Giovanni, who is instantly attracted by the young woman’s beauty. To woo her, he has to get rid of Biagio: he slaps him, he threatens him and, without any rights, all he can do is rue his station in life and curse her for betraying him. A me schiaffi sul mio viso! A me far un tal affronto!... (to Maturina) Ma gli schiaffi non li conto, Quanto conto, fraschettaccia, Che tu stai con quella faccia, A vedermi maltrattar. (to Don Giovanni) Ma aspettate. Ma lasciate. Ch’io mi possa almen sfogar. Da tua madre, da tua zia, Da tua nonna adesso io vado, Vo’ da tutto il parentado La faccenda a raccontar. Y The same situation is experienced as follows by Masetto: Ho capito, signor sì! Chino il capo e me ne vo. Giacché piace a voi così, Altre repliche non fo. Cavalier voi siete già. Dubitar non posso affé; Me lo dice la bontà Che volete aver per me. (to Zerlina, apart) Bricconaccia, malandrina! Fosti ognor la mia ruina! (to Leporello, who wants to knock him down) Vengo, vengo! (to Zerlina) Resta, resta. È una cosa molto onesta! Faccia il nostro cavaliere Cavaliera ancora te. 155 on notes (and skirts) between the two capitals 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 13. Ruggero Raimondi, il celebre Don Giovanni nell’omonimo film di Joseph Losey (1979). Ruggero Raimondi, the famous Don Giovanni in Joseph Losey’s film of the same name (1979). 14. Kiri Te Kanawa, la Donna Elvira di Losey. Kiri Te Kanawa, Losey’s Donna Elvira. 15. Per Donna Anna, Losey sceglie Edda Moser. Losey chose Edda Moser for the role of Donna Anna. 11:28 Pagina 156 Y No “fraschettacce”, no “nonne”, and how much more pain in Masetto’s realisation of the irremediable nature of his station in life, his inability to thwart Don Giovanni’s erotic plans on the very day of his wedding. Finally, the last meeting between Don Giovanni and the Commendatore, who has come to take and damn him. Giovanni Bertati’s version: Don Giovanni Siedi Commendator. Mai fin’ ad ora Credere non potei, che dal profondo Tornasser l’ombre ad apparir nel mondo. Se creduto l’avessi, Troveresti altra cena, Pure se di mangiar voglia ti senti, Mangia; che quel che c’è t’offro di core; E teco mangerò senza timore. Commendatore Di vil cibo non si pasce Chi lasciò l’umana spoglia. A te guidami altra voglia, Ch’è diversa dal mangiar. Y Da Ponte: The statue Don Giovanni, a cenar teco M’invitasti e son venuto! Don Giovanni Non l’avrei giammai creduto; Ma farò quel che potrò. Leporello, un’altra cena Fa che subito si porti! Leporello (appearing from under the table) Ah padron! Siam tutti morti. Don Giovanni (dragging him out) Vanne dico! The statue (to Leporello, who is speaking) Ferma un po’! Non si pasce di cibo mortale Chi si pasce di cibo celeste; Altre cure più gravi di queste, Altra brama quaggiù mi guidò! Leporello (La terzana d’avere mi sembra E le membra fermar più non so.) Don Giovanni Parla, parla, ascoltandoti sto. The statue Tu m’invitasti a cena, Il tuo dover or sai. Rispondimi: verrai Tu a cenar meco? Leporello (from afar, still trembling) Oibò; Tempo non ha, scusate. Don Giovanni A torto di viltate Tacciato mai sarò. The statue Risolvi! Don Giovanni Ho già risolto! The statue Verrai? Leporello (to Don Giovanni) Dite di no! Don Giovanni Parla dunque! Che chiedi! Che Don Giovanni vuoi? Ho fermo il cuore in petto: Non ho timor: verrò! The statue Parlo; ascolta! Più tempo non ho! 156 Y In this scene, the Mozart-DaPontian Don Giovanni must be as grand as is required by the moment at hand: if Leporello is trembling, he is worried about being accused of “viltate”, or cowardice. But the differences are not merely lexical. “Even though he is co- 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 157 eval, Da Ponte-Mozart’s Don Giovanni seems to belong to another musical and literary culture”, writes Daniela Goldin Folena. It is more tense and more restless that Bertati-Gazzaniga’s opera of the same name, eschewing its “regular little stanzas, [...] equally regular rhythm, unsurprising dynamics and predictable little melodies”. The differences, however, are mainly in the music: “Certainly, Gazzaniga didn’t go beyond the limits and language of opera buffa”, reflects Stephen Kunze, who has published an exhaustive work on the Venetian Don Giovanni. But the most explicit reflection on the potentiality of the subject is Mozart’s, who has the following to say about his first reaction to the idea: “My brain is afire; the subject comes to life before me all in one fell swoop. I do not hear the different parts of the orchestra separately, but all together. I can not say with what joy”. Y The choice of the protagonist’s voice is equally indicative: Gazzaniga opted for a tenor, which does not allow him to plumb sombre, dark or murky depths, all of which are explored with the bass voice chosen by Mozart for his Don Giovanni. Gazzaniga refuses to look the demonic in the eye, graciously keeping his distance. And the finale is written in the form of a tarantella: when Don Giovanni descends into the flames of hell, all the characters dance and invite everyone else to join them. No one declares they miss the lost excess; the music refuses to evoke its essence. “A style that is no longer modern”: Da Ponte’s pithy point can not be faulted, underlining as it does that each era has its own idea of modernity. But at the same time it is obvious, even from the three moments cited, that the main source for his text is Bertati. Da Ponte, in those months of 1787, was very much in a hurry, and an off-the-peg Don Giovanni suited him to the ground: while he was working for Mozart, he was also writing another two libretti, Axur, re di Ormuz for Antonio Salieri, and L’arbore di Diana for Martin y Soler. He made all three clients very happy. Y Unlike his more famous younger sibling (barely eight months younger, in fact), Bertati-Gazzaniga’s “playful drama” is also a declaration of love for the city that premiered the opera. The regality of the Venetian patriciate is toasted on stage: “Faccio un brindisi di gusto / a Venezia singolar. / Nei Signori il cor d’Augusto / si va proprio a ritrovar”. To the delights of Venetian women: “Alle donne veneziane / questo brindisi or presento, / music 0020.saggi.qxd 157 on notes (and skirts) between the two capitals 0020.saggi.qxd 158 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 158 che son piene di talento, / di bellezza e d’onestà. / Son tanto leggiadre / con quei zendaletti, / che solo a guardarle / vi muovon gli affetti”. To the nobility, women, the entire city: “Far devi un brindisi alla città, / che noi viaggiando di qua e di là, / abbiam trovato ch’è la miglior”. And the music accompanies this lay hymn to the Venetian dolce vita with a chivalry that can be gleaned in the glances, Pietro Longhi’s interiors and the festive aura that enlivens the passage through the Canalazzo in the paintings and colours of Canaletto. Don Giovanni’s passions are more insatiable and ruthless; too much so to be openly welcome in urban society. If in Venice the real Fallettis were sent to the gallows “that they may die” and Gazzaniga-Bertati’s Don Giovanni ends on a reassuring toast, in Vienna (where Mozart and Da Ponte’s “playful drama” debuted at the Burgtheater on May 5, 1788, with a few changes following requests from the singers and new insights from the authors) the reception is not favourable. Y “It is universally known that Mozart did not find the favour of success in Venice with these operas; after the first few performances, Don Giovanni was no longer performed for four years”, according to Gernot Gruber in his La fortuna di Mozart, the most exhaustive study of the reception of his production, and in this case referring to the triptych based on Lorenzo Da Ponte’s Italian libretti: The Marriage of Figaro (1786), Don Giovanni (1787), and Così fan tutte, which sanctioned the end of their collaboration in 1790. His chamber and opera works were repeatedly critically referred to as “overly spiced food”, “music which is not for all tastes” and “there is something wrong with his ear”. Vienna loved Mozart when he played his own music at the piano, when he improvised: “He had no rivals in phantasieren”, wrote his contemporaries. But not when he demanded to go beyond the dramatic and expressive conventions of the times. If even professional musicians thought they saw mistakes in the bolder harmonic inventions of his quartets, the people who flocked to the court theatres did not much care for the experiments that the librettist and composer were undertaking, with Joseph ii’s decisive complicity and support. Y It was the emperor, after all, who had allowed the production of the opera based on Beaumarchais’ subversive play, which Austria’s censors had refused to allow onto the stages in German. He had facilitated Don Giovanni’s premiere in Vienna after its successful stint in Prague; he himself had encouraged the genesis of the story, which was then considered scandalous, of Così fan tutte, where 22-07-2009 16. Giacomo Casanova, Autografo con l’Aria di Leporello, aggiunto al libretto di Da Ponte per il Don Giovanni di Mozart, Praga, Státni Archiv. Giacomo Casanova, Autograph with Leporello’s Aria, added to the libretto by Da Ponte for Mozart’s Don Giovanni, Prague, Státni Archiv. 11:28 Pagina 159 two pairs of young lovers betray then forgive each other, without any drama, governed in their sentimental musical chairs by a cynical philosopher, Don Alfonso, for whom fidelity, conjugal duty and the sacrality of the family are empty husks. These were three very bold works for that period. How to interpret the desire to be the centre of attention demonstrated by the servant Figaro, who is much more inventive and enchanting than the Count, who is still in two minds about the feudal ius primae noctis he had abolished after endless second thoughts, and who is obsessed with Susanna, the beautiful chambermaid who, betrothed to Figaro, works for the much-betrayed Countess. Y And, as the ambassadors to Paris were beginning to send worried despatches regarding the political climate in France, the aristocrat Don Giovanni’s solemn invitation, delivered at first when he is alone and in full voice then along with the chorus of peasants, to the three masked men who ask to be allowed into his party, must have sounded appalling: “È aperto a tutti quanti – Viva la libertà” (lit. “It is open to all – Long live liberty!”). “Mozart realised what had been imposed by the demonic spirit of his own genius, by which he was possessed”, wrote Goethe when talking about Don Giovanni, perfectly intuiting its dark, pre-Romantic hues. If Prague’s bourgeoisie applauded this daring, how could the “classical” and devoted nobility of Vienna welcome or approve these scandalous themes? The death of Joseph ii in 1790 ushered in, for Mozart, the most desperate phase of his private and professional existence. Following the loss of his most enlightened patron, he would not bounce back until 1791, that is virtually the final, and most incredibly productive, months of his life. But his operas in that phase dealt with very different themes: La clemenza di Tito, dedicated to Leopold ii when he was crowned king of Bohemia, and The Magic Flute, which were, respectively, an “institutional” work in Italian and a philosophical fable for the more popular theatres and general public in Vienna. These were both successful, and came at the end of an artistic career that the capital of the empire had, on brief occasions, embraced with enthusiasm, and on other, decidedly longer, occasions looked on with indifference if not outright aloofness. music 0020.saggi.qxd 159 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 160 1. Giovanni Antonio Canal detto Canaletto, Capriccio con i cavalli della Basilica di San Marco posti sulla piazzetta, Windsor Castle, Royal Collection; potrebbe aver ispirato Antonio Canova per un progetto di ripristino della quadriga dopo il rientro da Parigi. Giovanni Antonio Canal, known as Canaletto, Capriccio with The Horses of St Mark’s Basilica, Windsor Castle, Royal Collection. This might have inspired Canova’s project for a restoration of the quadriga on its return from Paris. 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 161 sotto la dominazione austriaca esiste già una “banda del buco” «vendere a ogni costo»: spariscono 5000 dipinti, ma tornano cavalli e leone Rosella Lauber Y Che cosa sarebbe successo se, per il rifiuto della giuria del Salon parigino, fossero stati ridotti in stracci, o in legna, quadri di Cézanne, Pissarro e Courbet, o dipinti quali la Ragazza in bianco di Whistler, o Le déjeuner sur l’herbe di Manet? Fortunatamente, quando nel 1863, a Parigi, la commissione esclude 3.000 opere su 5.000, Napoleone iii ordina di aprire il Salon des Refusés; qui, fra l’ammirazione di Zola e le critiche ilari del pubblico, si creano le premesse per la prima mostra dell’impressionismo del 1874, dove Monet espone il suo Impression, soleil levant, che segna una svolta epocale. Invece, eventi tali da condurre alla distruzione di migliaia di «dipinti rifiutati», convertiti in pura tela, o in legname «da fuoco», sono testimoniati a Venezia alcuni decenni prima, sotto la seconda dominazione austriaca, e in particolare nel 1821. Una vicenda significativa, che ricostruiamo anche attraverso documenti e nuovi riscontri archivistici appena rintracciati. Y Nessun Salon des Refusés è sollecitato fra le lagune da Francesco i d’Austria (fig. 2) per oltre 3.000 quadri valutati di «assoluto scarto» da una commissione che vaglia circa 5.000 opere, concentrate da Venezia e dal Veneto e incamerate dal Demanio dopo le soppressioni napoleoniche. La speciale giuria è riunita su istanza del presidente dell’Accademia di Belle Arti, Leopoldo Cicognara (fig. 3), ed è composta dai pittori e professori «Liberal Cozza, Lattanzio Querena, Antonio [sic] Borsato», diretti dal segretario Antonio Diedo, architetto. Dal 29 maggio al 18 luglio 1817 vengono esaminate le opere, il cui destino è già stabilito dai decreti governativi del 21 marzo e del 29 aprile 1817, con cui si prevede «di alienare mediante pubblica asta» i dipinti demaniali di «assoluto scarto» e anzi «di lavarli tutti per poi venderli, anche col riflesso che dalla vendita di quelli quadri come tele si potrà forse ottenere un ugual vantaggio che dalla loro vendita come pitture»; si ritiene inoltre «conveniente di ricercare prima il voto» del presidente dell’Accademia, in quanto l’argomento «oltre l’interesse del Demanio riguarda anche la vista d’impedire il dete- l’indagine 0020.saggi.qxd 161 sotto la dominazione austriaca esiste già una “banda del buco” 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 2. Antonio Canova, Busto di Francesco I d’Austria, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. Antonio Canova, Bust of Francis I of Austria, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. 162 11:28 Pagina 162 rioramento delle Belle Arti». Oltre a 200 quadri demaniali «meritevoli» di conservazione, selezionati in precedenza dal professore Baldissini e di cui si approva il trasporto a Sant’Apollinare «per poi disporli in uso pubblico o privato», si salvano 500 opere giudicate «degne» dalla commissione; l’alienazione «col massimo vantaggio» attende invece «la massa degli scarti […] pressoché infinita». I dipinti di «scelta riserva» si distinguono in tre categorie: quadri per l’Accademia (i rari di «antico penello»); da destinarsi alle chiese (grandi e medi, ben conservati, di «buon penello» e qualità); da vendere (grandi e piccoli, «di buon penello, di lodevole maniera» e se restaurati riconducibili a superiore pregio, per trovare «un più felice ed utile esito nel commercio, aspirando il dilettante e speculatore»). Il 18 maggio 1817, previo parere accademico e per evitare il «rischio d’infettare il commercio di cattive pitture a disonore dell’arte pittorica», si delibera di lavare i dipinti scartati, «per poi verificarne l’asta come tela», con il «possibile maggiore interesse dell’Erario». Y Invece del lavaggio delle tele, «lavoro immenso e dispendioso», sarà approvato infine, come «il più conveniente», un «progetto di distruzione della pittura delli quadri di scarto, e vendita delle tele e legname», presentato dall’economo Antonio Pasquali il 9 agosto 1817. Prevede «la contorciatura del dipinto, cancellatura del figurato con una liscia ben forte, e densa mesta [...], o spezzatura del dipinto nel luogo che più lo deformi. Ognuno di questi espedienti da usarsi secondo la qualità del dipinto, staccato prima dal telaio o soaza, viene a distruggere la pittura, e conserva in miglior preggio la tela», asciutta, e dalla quale è ricavabile un profitto, cui si aggiunge «l’altra utilità ritraibile dal legname. In quanto al quadro in legno si distruggerà il figurato e dipinto spezzandolo, riducendolo ad uso di legna da fuoco». Pasquali dettaglia la procedura: «Prima separare il legname tutto dalla tela» e «cancellare poi in quella tela qualunque rilevante segnale di Pittura nelle maniere sopra espresse, e distruggere finalmente il quadro in legno riducendolo a pezzi da fuoco». L’economo propone: «Questa Superiorità avrà la compiacenza di decidere se della 22-07-2009 3. Francesco Hayez, Ritratto della famiglia Cicognara, con il busto colossale di Antonio Canova, Venezia, collezione privata. Leopoldo Cicognara è seduto accanto alla seconda moglie, Lucia Fantinati, e al figlio di lei Francesco. Francesco Hayez, Portrait of the Cicognara Family, with large bust of Antonio Canova, Venice, private collection. Leopoldo Cicognara is seated next to his second wife, Lucia Fantinati, and her son Francesco. 11:28 Pagina 163 massa di quadri di scarto sarà da tenersi un elenco soltanto numerico, o distintivo colle corporazioni e marche, operazione da eseguirsi all’atto di separare il legname dalla tela». Le autorità appoggiano «l’esecuzione del piano», ma rispondono che «si crede inutile poi il tenere un elenco dei quadri da distruggersi». Inoltre, si vieta la vendita a privati delle opere scartate, non consentendone la “ridipintura” «ad altro uso», quali addobbi per le camere, difficilmente sorvegliabile, affinché «non se ne spargesse in commercio». Y Il governo conferma l’asta pubblica, successiva alla «distruzione» di ogni segno figurativo nelle opere «di nessun valore di penello», da trasformare in stoffa e in ciocchi di legno. Il 22 novembre 1817, Pasquali presenta il capitolato d’asta in nove punti, dove informa che «tela e legname sono ostensibili agl’aspiranti nel locale già Scuola di San Giovanni Evangelista», e la trattativa si aprirà dopo «perizia del valore degli effetti». Il 10 gennaio 1818, la stima indica «che si potrebbe aprire l’asta al valore di lire mille e duecento», anche se l’ingegnere e l’economo incaricati confessano che la «non perfetta cognizione [...] sopra tali generi potrebbe forse aver preso qualche equivoco». Y Nell’ex Scuola di San Giovanni Evangelista, l’asta è bandita il 29 novembre 1821. Nel frattempo, in esecuzione all’atto del 26 maggio 1820, si staccano dalle pareti «quadri di scelto penello e ricordanti fatti patri», cioè i dipinti di Bellini, Mansueti, Carpaccio, Bastiani, Diana, da consegnare all’Accademia (fig. 4). In un sol giorno, l’ambiente è svuotato da quelle migliaia di «tele, cornici e legnami di scarto» alienate nel 1821, per la modica somma di 1.031 lire, come certifica ora un «processo verbale» del 28 gennaio 1822, sottoscritto da Pasquali e dal vincitore della trattativa. Costui era stato invitato a versare «l’offerto prezzo di L. 1.031» e a procedere con lo «sgombro del locale» senza danneggiarlo, come specifica l’atto dell’11 gennaio 1822, che fa seguito alla ricevuta di «superiore approvazione» dell’esito del 29 novembre 1821, e inviata con dispaccio del 27 dicembre. Il com- l’indagine 0020.saggi.qxd 163 sotto la dominazione austriaca esiste già una “banda del buco” 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 4. Vittore Carpaccio, Miracolo della reliquia della Croce al ponte di Rialto, Venezia, Gallerie dell’Accademia; appartiene al ciclo che decorava le pareti della Sala dell’Albergo o della Croce, nella Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista: in seguito alle soppressioni, i dipinti furono consegnati alle Gallerie nel 1820. Vittore Carpaccio, Miracle of the Relic of the Cross on the Rialto, Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia. The painting belongs to a cycle decorating the walls of the Sala dell’Albergo o della Croce, Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista. Following religious suppression under Napoleon, the paintings were consigned to the Gallerie in 1820. 164 11:28 Pagina 164 pratore si presenta il 17 gennaio per ottenere il permesso all’asporto degli oggetti, concesso dopo il versamento in cassa, previa restituzione dei «venti talleri» di cauzione. In calce al documento si distingue la sua firma: «Nicholò Brazzoduro». Y Rintracciamo lo stesso nome in alcuni preziosi registri, sinora ritenuti perduti, che certificano gli «Acquirenti di effetti mobili, e quadri avocati dalle soppresse corporazioni religiose». Qui troviamo anche alcune partite di dare e avere riferite a Niccolò Brazzoduro nel 1811, per un totale di 1.021 lire: il 18 febbraio è registrata la spesa di 550 lire «per l’acquisto di alcuni effetti del soppresso Monastero di Santa Giustina»; e il 29 giugno è segnata quella di 471 lire «per simile, erano del soppresso Monastero di San Mattia di Murano». Tali nuove attestazioni d’archivio integrano il profilo di Brazzoduro, già in parte delineato. Rigattiere e imprenditore edile, si assicura la chiesa dei Servi, ma per ricavarne materiale da costruzione: tanto che nel 1821 era «quasi del tutto atterrata». Nel 1807, il 20 aprile si aggiudica all’asta, per 364 lire, 20 parapetti dell’altare di Santa Croce della Giudecca; e il 31 dicembre rileva libri dalla biblioteca di San Giorgio. Nel 1809, il 12 marzo, compra l’organo di San Giovanni di Malta; e acquista la grata del coro dei Santi Marco e Andrea di Murano, «con oro consunto [...] del peso di 426 libbre a lire it. 76,291». Y Le alienazioni, compresa quella clamorosa del 1821, già nel 1830 suscitano interrogativi. Scopriamo infatti utili registrazioni in un fascicolo di documenti non noti, dedicati alla ricerca del «destino dei due quadri del Tiziano e del Cima, esistenti in mano di privati», sfuggiti all’Accademia e invece individuati «il primo presso la vedova del negoziante pittore Baldissini, ed il secondo presso certo Bortolo Giraldon» (ovvero il Compianto, Mosca, Museo Pushkin). Un atto d’inizio febbraio 1830 informa che il dipinto tizianesco era passato «da Baldissini a Bortolo Adami, che tuttora lo possede e che dichiara di averlo acquistato da quella famiglia, come dalla detta deposizione fatta per effetto “di invito” al commissario di Polizia di Canaregio»; s’incrociano così nomi di pittori e/o compratori (e quello di Adami compare anche nel ritrovato registro degli Acquirenti). Soprattutto rileviamo, nello stesso incartamento, un’interrogazione del 19 aprile 1830: «Se sotto il cessato regime italico ed in quale altra epoca sieno stati distrutti con o senza il giudizio accademico alcuni dipinti». Un dirigente dell’Ispettorato Demaniale, infatti, così chiede a Pasquali, come persona informata sui fatti e «per l’ingerenza avutane». Si 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 165 esigono notizie «sull’epoca in cui si propose, e su chi propose la distruzione dei quadri di rifiuto adottata dal Governo attuale, e compiuta poi colla vendita delle tele risultanti nell’anno 1821»; tanto più che non si conosce «veramente che durante il cessato Governo sia nata alcuna distruzione di quadri, mentre gli atti [...] indicano soltanto che dopo la scelta fatta da Edwards, e dai Professori Appiani, e Fumagalli sia stata soltanto ordinata, o sollecitata sempre la vendita ad ogni costo». La risposta di Pasquali giunge il 30 aprile: «La vera distruzione delli dipinti e vendita delle tele e legnami si verificò precisamente sotto l’attuale Governo»; ne dettaglia le modalità, con la conferma che mai s’era verificata «distruzione di Pitture sotto il cessato Regime», anche perché era «ben lontano [...] di non infettare il commercio con pitture di scarto», preferendo anzi vendere pure i «più infimi rifiuti. Vedasi l’esito fatto più volte per aste di quadri». Y Intanto, nei depositori demaniali continuano a confluire beni; a volte ne fuoriescono, ma non per volere delle autorità. È il caso di alcuni “furti d’arte”, i cui fascicoli processuali svelano ora dinamiche sorprendenti. Il 4 maggio 1827, si comunica al Presidio di Governo la convocazione d’urgenza di Pasquali, «dietro avviso del Commissario Superiore di Polizia del sestier di San Polo», presso il «deposito di quadri ed altri oggetti Demaniali» di San Giovanni Evangelista. L’economo è chiamato «ad eseguire una visita per verificare un sospetto di furto». Era stato infatti notato che «da una finestra respiciente sopra un orticello privato s’erano introdotti de’ mal intenzionati sollevando una grossa ferriata da cui era difesa, ed asportando ramate, ed invetriate, ed alquanta ferramenta infissa nel locale». Il 5 maggio, una commissione si reca a «eseguire cogli inventari alla mano l’incontro dei quadri, ed effetti del depositorio»: risultano sottratti dieci dipinti, oltre a «sei mascheroni di bronzo levati dalle porte interne del locale». Il tribunale criminale procede «all’Inquisizione, ma è privo di dati o sospetti sopra le persone del delitto», e dalle deposizioni emerge solo «un ferro detto leva rinvenuto ed abbandonato dai delinquenti». Fra i documenti ritrovia- l’indagine 0020.saggi.qxd 165 sotto la dominazione austriaca esiste già una “banda del buco” 0020.saggi.qxd 166 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 166 mo l’elenco delle opere trafugate, incluse le provenienze: Santi Giovanni e Paolo, San Giorgio Maggiore, Santa Lucia, la Scuola dei Mercanti dell’Orto, il Monastero delle Dimesse di Veronica; dalla Commissaria Sagredo, oltre a una Veronica e a una Santa con angioletti, manca una tavola del Redentore, di cui «è rimasta la cornice»; mentre della tela con Gesù adorato dalla Madre, e da altri divoti, già agli Incurabili, resta il telaio. Y Il 15 settembre 1827, si comunica al Presidio di Governo un altro furto a San Giovanni Evangelista, che ha eluso sia le misure di sicurezza adottate, sia la vigilanza delle «notturne pattuglie» nonché del «numeroso satellizio», ovvero agenti “in borghese” dei “satelliti”, cioè guardie civili di polizia (che in quell’anno, secondo le statistiche, sono 183). Il rapporto dell’economo Pasquali dettaglia la «perlustrazione del locale alle ore cinque pomeridiane» conseguente a sospetti di «nuovi derubamenti». Una prima ispezione non rivela alcun indizio, neppure raggiunta la sala superiore attraverso lo scalone codussiano (fig. 5); «ma volendo esaminare se mai fosse stato aperto l’ingresso che conduce al tetto mediante scala segreta entro il muro maestro della sala, la di cui porta nella parete era coperta di quadri, nell’uno di questi si venne a riconoscere una cornice dalla quale venne effettivamente levata la tela dipinta. Da questo nacque la certezza dell’introduzione de’ malintenzionati». Le ricerche si replicano serrate, e «si venne a ritrovare aperta la porta che dalla grande sala conduce alle due stanze ove ritrovasi l’altare detto della Croce, la qual porta veniva fermata con catenaccio al di dentro». Raggiunta la seconda stanza dietro l’altare, si appura «il trasporto di un grande quadro in tavola dal luogo dove prima rimaneva, e levato il medesimo si ebbe tosto con sorpresa a riconoscere l’apertura di un foro nel muro che veniva tolto alla vista colla posizione del quadro. Questo foro è quell’istesso fatto altra volta, 22-07-2009 5. Mauro Codussi, Scalone, Venezia, Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista; dà accesso al piano nobile, dove furono scoperti i furti d’arte del 1827, ed è citato nei verbali. Mauro Codussi, Staircase, Venice, Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista. The staircase leads to the piano nobile, where the art thefts were discovered in 1827. 11:28 Pagina 167 e rilevato nel processo del giorno 5 maggio, il quale allora servì d’introduzione alle due stanze susseguenti e alle soffitte». Smascherato così l’espediente dell’antesignana “banda del buco”, s’individuano infine, «nella soffitta superiore alla stanza dell’altare della chiesa, indizi sospetti da un basso luminare», riconosciuto come «il luogo dell’introduzione, essendosi trovati manomessi dei coppi, e rinvenuto giacente un cosiddetto sgaruccio a manico serrato». L’indagine prosegue per comprendere «da qual parte se da terra o per acqua facevano scesa ai tetti per introdursi nella soffitta». Gli interrogatori anche del vicinato rievocano movimenti sospetti all’imbrunire, rumori e persino «persone che caddero nell’acqua» «nel rivo locale», oltre a battelli in avvicinamento recanti scale. Gli stessi «malintenzionati» di primavera, «conoscitori del locale», erano dunque tornati ad agire, raddoppiando il bottino. Fra i documenti rintracciamo il «prospetto dei quadri ritrovati mancanti» nei sopralluoghi del 17-19 settembre 1827: elenca 21 opere trafugate, compresa «La Presentazione al tempio di Maria opera del Peranda», ovvero Sante Peranda. Restano frammenti di legname, o il «telaio intero», e «due quadri degli esistenti vennero spogliati delle rispettive cornici dorate». Y Oltre a polizia e a centralizzazione burocratica, il governo asburgico a Venezia dirige a lungo una complessa politica culturale nella seconda dominazione austriaca (1814-1848) e nella terza (1849-1866), intervallate dai fatti del 1848-1849 e succedutesi al primo Governo austriaco (1798-1805), dopo il trattato di Campoformio. Intercorrono altri otto anni, quelli “francesi” sotto il Regno Italico (1806-1814), avviati con le soppressioni napoleoniche di corporazioni religiose, monasteri e chiese, confraternite e scuole, decretate dal 1806 al 1810, e l’avocazione al Demanio dei rispettivi patrimoni. Capolavori artistici sono concentrati e inventariati in depositori quali l’ex Scuola di San Giovanni Evangelista e l’ex Commenda di Malta. Si spediscono in Francia o in Lombardia i migliori quadri, e centinaia si assegnano alle nuove pinacoteche delle Accademie di Belle Arti, sia a Venezia, nella riadattata Carità, sia a Milano, selezionate per Brera dai commissari Appiani e Fumagalli. Opere «non prescelte per la Corona» si destinano alla vendita; s’indicono ripetute aste pubbliche, deprezzate o deserte per l’inflazione e il crollo economico. Y La trasformazione dello status di opere d’arte imposta dall’alto s’innesta tuttavia in un latente movimento progressivo di passaggi di proprietà, oltre a scalarsi dopo provvedimenti quali la raziona- l’indagine 0020.saggi.qxd 167 sotto la dominazione austriaca esiste già una “banda del buco” 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 6. Vittore Carpaccio, Disputa di santo Stefano tra i dottori nel Sinedrio, Milano, Pinacoteca di Brera; apparteneva a un ciclo con le Storie di santo Stefano, per l’omonima Scuola a Venezia, disperso nel 1806 in seguito alle soppressioni napoleoniche. Vittore Carpaccio, The Disputation of St Stephen, Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera. The painting belonged to a cycle of the Stories of the Life of St Stephen, for the Scuola of Santo Stefano in Venice; the cycle was lost in 1806 following the Napoleonic suppression. 168 11:28 Pagina 168 lizzazione della finanza pubblica e la riduzione della manomorta: già deliberati dal Senato veneziano sin dal 1768 e tali da determinare un’imponente circolazione di oggetti d’arte, pure fra mercanti e collezionisti. Gli interventi tra Sette e Ottocento sul patrimonio artistico e demaniale veneto – approfonditi dai fondamentali studi di Spiazzi e Schiavon, Zorzi, Olivato, Pavanello e Romanelli – manifestano aspetti in bilico fra continuità e innovazione. Gli austriaci a Venezia si dimostrano sensibili verso opere emblematiche. In seguito alla caduta di Napoleone e al Congresso di Vienna, si restituiscono all’ex Dominante codici e oggetti d’arte, in particolare dai francesi; non invece da Brera (fig. 6), né dalle chiese lombarde. All’avvio del secondo Governo austriaco, e dopo l’istituzione del Lombardo-Veneto il 7 aprile 1815, si verifica un trionfale segno di restaurazione, fra le gondole e le “pietre di Venezia”: l’aquila asburgica ritorna, accompagnata dai cavalli e dal leone di San Marco. Y Infatti, 18 anni prima, nel dicembre 1797, i francesi avevano sottratto anche la quadriga bronzea marciana (fig. 7), poi collocata da Napoleone sull’Arc du Carrousel. Quando saranno i vincitori austriaci a staccare i cavalli dal carro di trionfo svettante fra il Louvre e le Tuileries, per evitare sommosse dei parigini agiranno di notte e con il presidio di militari, che scortano pure il convoglio partito da Parigi il 17 ottobre 1815 con le opere restituite all’Italia e al Vaticano, soprattutto per merito di Canova (fig. 8). Grazie all’artista e a Schwarzenberg, e per volontà dell’imperatore, il 13 dicembre 1815 i quattro cavalli, simbolo dell’identità veneziana, approdano nel bacino di San Marco (fig. 15), salutati dal riecheggiare di un «universale urrà». Y I destrieri sono restituiti al cospetto di Francesco i, del principe di Metternich e di alti dignitari. Vincenzo Chilone eterna il momento nella tela ora in collezione Treves de’ Bonfili (fig. 9); un capriccio di Canaletto (fig. 1) sembra evocato dal progetto di Canova di collocare i cavalli su alti basamenti dinanzi a Palazzo Ducale. Cicognara dedica all’evento una narrazione storica e in una prolusione celebra il ritorno, con gli austriaci, di opere «reduci 22-07-2009 7. Jean Duplessi-Bertaux, La conquista di Venezia, incisione; ritrae il momento in cui i quattro cavalli marciani sono prelevati dai francesi quale bottino di guerra, per essere trasportati a Parigi. Jean Duplessi-Bertaux, Enlèvement des chevaux de la basilique Saint-Marc de Venise, engraving. The work depicts the removal of the four horses of St Mark’s Basilica by the French as war booty. The horses were then transported to Paris. 11:28 Pagina 169 dalla Senna», compresi il leone marciano (fig. 10) e il Giove Egioco (fig. 11). Nel 1817, lo stesso Cicognara tramuta in commissioni ad artisti locali la richiesta di un tributo di 10.000 zecchini, imposto per le quarte nozze di Francesco i con Carolina Augusta di Baviera; giunge così a Vienna l’Omaggio delle Provincie venete (fig. 12): mobili, tele, sculture, guidati dalla Polymnia di Canova, esposta poco prima in Accademia, accanto all’Assunta di Tiziano, definita il «più bel quadro del mondo». Y Nel frattempo, edifici privati e religiosi sono demoliti o diventano osterie, mulini, magazzini, caserme e «bagni penali»; chiudono teatri (nel 1824 quello di San Moisè è trasformato in falegnameria); monumenti e altari si smantellano in materiali di recupero e pietre da costruzione, specie tra il 1813 e il 1820. Venezia resta sempre «una città delle Mille e una notte», come il principe Clemente di Metternich scrive alla moglie il 10 luglio 1817, con il canale della Giudecca e il Canal Grande «letteralmente ricoperti di gondole» (fig. 13), i caffè aperti e il popolo sveglio fino all’alba; ma, annota nel diario la principessa Mélanie di Metternich quando arriva da Fusina nel settembre 1838, lo «spettacolo grandioso» offerto a chi approda (fig. 14) si alterna nei canali alla tristezza delle dimore in rovina. Dagli anni venti dell’Ottocento si avviano interventi edilizi per case e ponti. Dal ghetto, le cui cancellate furono distrutte nel 1797, prosegue la “fuoriuscita” anche dei non più interdetti investimenti immobiliari, da parte di famiglie ebraiche con forte potere d’acquisto. Dapprima, si estendono nelle adiacenze; poi, giungono sino a Rialto, a San Marco e lungo il Canal Grande; così, la Ca’ d’Oro, già «bene rovinoso», sarà acquisita da Moisè Conegliano, per passare nel 1846 al principe Trubetzkoi, che ne fa dono alla ballerina Maria Taglioni. Nel 1827, Isacco e Jacopo Treves de’ Bonfili, banchieri, acquistano palazzo Barozzi Emo sul rio di San Moisè; dove si crea uno scenografico ambiente per accogliere dallo studio romano di Canova i suoi Ettore e Aiace, acquistati per 55.000 lire (fig. 16). Y Vendite massicce di beni a Venezia erano da tempo incrementate dalle difficoltà finanziarie, acuitesi dopo le requisizioni na- l’indagine 0020.saggi.qxd 169 sotto la dominazione austriaca esiste già una “banda del buco” 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 8. Giovan Battista Lampi, Ritratto di Antonio Canova, Vienna, Österreichische Galerie. Giovan Battista Lampi, Portrait of Antonio Canova, Vienna, Österreichische Galerie. 170 11:28 Pagina 170 poleoniche, nonché dal blocco del 1813-1814, con la successiva crisi, tra epidemie, inondazioni, carestie. La contingenza grava a lungo e, nel 1825, giunge a Francesco i una relazione, comprensiva di confronti con il 1797 e rimbalzata sul «Times» e sul «Journal des Débats», redatta dal patriarca Pyrker (mecenate di artisti viennesi a Venezia, ma anche promotore, fortunamente inascoltato, dell’abbattimento dell’iconòstasi marciana). Le statistiche confermano la situazione nel 1827: i commercianti calano da 10.884 a 3.628; gli artigiani da 6.200 a 2.442; i lavoratori dell’Arsenale da 3.302 a 773; mentre scendono da 1.088 a 607 i gondolieri ai traghetti, e da 2.854 a 297 quelli «da casada»; su una popolazione ridotta da 136.000 abitanti a 100.556, 40.764 sono i bisognosi di sussidi. L’imperatore, «per aiutare i buoni Veneziani», che gli tributano consensi (fig. 17), sollecita risoluzioni: e Pyrker invoca l’estensione del Porto Franco, concesso il 20 febbraio 1829 (fig. 18). Intanto, i privati cedono monete, medaglie, dipinti e sculture, nonché collezioni e biblioteche, spesso a stranieri, anche austriaci. Y Le premesse del fenomeno s’individuano, sin dagli ultimi decenni della Serenissima, pure leggendo l’epistolario di Apostolo Zeno, tra i fondatori del «Giornale de’ letterati d’Italia» e poeta cesareo alla corte di Vienna: se da un lato il veneziano denuncia come «a poco a poco l’Italia va perdendo il meglio [...]; ma non è da stupirsene, perché vi va mancando il denaro, il gusto e lo studio», egli stesso nel 1748 vende a «un tedesco» la propria raccolta di monete, poi passata in Austria, a San Floriano. Anton Maria Zanetti riceve invece pietre e cammei antichi, a Vienna, in cambio di consigli per la collezione del principe del Liechtenstein: dove sarebbero poi confluiti, attraverso l’antiquario Guggenheim, anche i due rilievi da Palestrina ora al Kunsthistorisches Museum (fig. 19) e sino al secolo xix posseduti dai Grimani. Altri marmi di questa raccolta, ancora ammirata nel 1822 da visitatori come Thiersch, risultano in vendita nel 1831 presso l’antiquario Sanquirico, mentre diversi pezzi, offerti invano da Michele Grimani a Francesco i, passano attraverso mercanti quali Weber, Richetti, Pagliaro, sino a raggiungere grandi clienti tedeschi e austriaci. Y Si può ripercorrere un flusso progressivo dalle raccolte lagunari a quelle viennesi, come nel caso di lastre a rilievo attiche, passate dal Museo Trevisan-Suarez alla grandiosa collezione Obizzi al Catajo (Battaglia Terme) e quindi insieme a questa giunte a Vien- 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 171 na. Qui, a inizio Ottocento, si ritrova anche parte della raccolta Garzoni, divisa fra Austria e Costantinopoli. Intorno al 1820, Girolamo Silvio Martinengo propone il suo museo al governo austriaco che, ottenuta la stima, declina l’offerta del conte, rinnovata invano dalla vedova Elisabetta Michiel: tanto che la collezione sarà rilevata nel 1836 anche dal mercante Fontana di Trieste, prima di venire dispersa in tutta Europa. Nel 1821, pezzi del medagliere di Domenico Almorò Tiepolo si vendono a Francesco i. Y L’imperatore, nel 1805, aveva acquistato, ma per l’Accademia di Venezia, alcuni calchi e gessi dalla raccolta Farsetti, compresi modelli in terracotta di Bernini. Emblematico un annuncio di Cicogna nei suoi Diari inediti, il 3 febbraio 1817, allorché Antonio di Giacomo Nani sigla la vendita en bloc a Francesco i della collezione di San Trovaso, «uno de’ nostri più belli musei, che partir deve per Vienna», in cambio di «90.000 ongari d’oro» pagati a rate, «perché il Nani rifiutò l’offerta di beni demaniali, e di fondi nel territorio austriaco. È manco male che vada via di qua tutto intero». Cicogna rettifica, il 7 aprile 1817: «Non va più venduto il Museo Naniano, e resterà qui, se pure non verrà squartato dai creditori», minacciosi «di portargli via il meglio e il buono». La notizia torna nelle note di Fapanni (vedi «VeneziAltrove» 2005), critico contro i «Reverendi Antiquarii» e «gli onorevoli Sensali e faccendieri», che «venderebbero anche la chiesa di San Marco, se potessero, agli stranieri». Francesco i si dimostra restio a fuoriuscite di oggetti d’arte dalle lagune, nonostante le continue offerte dei collezionisti: spesso, gli stessi discendenti di casate descritte negli Arbori di Barbaro, il cui codice più attendibile si trova a Vienna fra i volumi già Foscarini, sequestrati dal fisco a Giacomo, pronipote del doge Marco. Y I provvedimenti austriaci verso l’arte a Venezia sono articolati rispetto ai principi della tutela del patrimonio e del controllo del mercato artistico. Sin dal 1816, 14 pezzi fra i migliori partono per Vienna. Qui, nel giugno 1838, il principe di Czernin riceve 18 casse, con 76 dipinti per il Belvedere; in agosto, tramite Metternich, arrivano altri 26 colli con 85 quadri diretti all’Akademie der Bil- l’indagine 0020.saggi.qxd 171 sotto la dominazione austriaca esiste già una “banda del buco” 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 9. Vincenzo Chilone, La cerimonia del ricollocamento dei cavalli bronzei sul pronao della Basilica di San Marco, Venezia, collezione Treves de’ Bonfili. Vincenzo Chilone, Replacing the bronze horses on the pronaos of St Mark’s Basilica, Venice, Treves de’ Bonfili collection. 10. Richard Parkes Bonington, La colonna di San Marco, Londra, Tate Gallery; ritrae il Leone marciano, una delle opere già sottratte da Napoleone che tornano dopo il Congresso di Vienna. Richard Parkes Bonington, St Mark’s Column, London, Tate Gallery. The work depicts one of the works removed under Napoleon and brought back to Venice after the Congress of Vienna. 172 11:28 Pagina 172 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 173 denden Künste (restituiti dopo il 1919). A Venezia riprendono aste e vendite, spesso previo parere di rappresentanti dell’Accademia, contro cui il pittore Odorico Politi sferra un’accusa, riportata da Cicogna nei Diari il 19 marzo 1819, di monopolio «sopra i quadri di ragion pubblica che stanno nella Commenda di Malta, e che si vendono sotto mano e si cambiano, senza che lo acconsenti il Governo, con danno delle nostre rarità, e con guadagno illecito di chi vi ha parte». Che qualche professore sia coinvolto nel mercato, anche onesto, trova conferma in epistolari coevi. Così, il 3 luglio 1802 Ferdinando Tonioli già consiglia a Canova il nome di «Baldicini», cioè Giuseppe Baldissini, figlio d’arte dell’accademico Nicolò, tra i «Negozianti di Quadri» dotati di «cognizione unita ad una certa probità». Y Per l’Accademia veneziana l’imperatore acquista pure opere, quali i disegni della raccolta Quarenghi nel 1824 (vedi «VeneziAltrove» 2004), preceduti nel 1822 da quelli della collezione Bossi, incluso l’uomo vitruviano di Leonardo (fig. 20), su sollecitazione di Cicognara. Le ripristinate Fabbriche di Rialto accolgono gli uffici giudiziari, rimossi da Palazzo Ducale per scongiurarne l’incendio anche dopo quello della Ca’ Grande dei Corner del 1817, e soprattutto in seguito al focolaio che, nel 1821, aveva minacciato la sala del Maggior Consiglio (poi il 13 dicembre 1836, brucerà la Fenice, subito ricostruita e riaperta il 26 dicembre 1837). Dopo il 1822, come riscontriamo in una Memoria del conservatore Corniani degli Algarotti datata 7 marzo 1827 nel fondo del Magistrato Camerale, arrivano nel depositorio dell’ex Commenda di Malta «molti pezzi dal Palazzo Grimani ora Ufficio Generale delle Poste, altri del Palazzo Corner presentemente Ufficio dell’Imperiale Regia Delegazione». Dal 1817, l’Archivio di Stato è concentrato nel convento dei Frari. Nell’adiacente chiesa, prima del monumento a Tiziano sovvenzionato dall’imperatore, s’inaugura nel 1827 quello a Canova (morto cinque anni prima in casa del proprietario del Caffè Florian). Tra i finanziatori della sottoscrizione per il cenotafio, promossa da Cicognara (fig. 21), spiccano Francesco i e la moglie, oltre al primo ministro britannico, seguiti da re, banchieri, uomini di cultura quali Byron, Quatremère de Quincy, Alessandro Volta. Intanto, a chiese e a fabbricerie che li richiedano, si distribuiscono beni concessi per la «pietà del Governo a semplice uso e a titolo di custodia». Y Nel 1817, si avverte l’urgenza d’inventariare il patrimonio artistico e le proprietà ancora a disposizione del Demanio. La com- l’indagine 0020.saggi.qxd 173 sotto la dominazione austriaca esiste già una “banda del buco” 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 11. Cammeo con Giove Egioco, detto Cammeo Zulian, Venezia, Museo Archeologico Nazionale; già nella collezione di Girolamo Zulian, è trafugato dai francesi nel 1799 e restituito nel 1815. Cameo with Zeus Aegiochus, also known as the Zulian Cameo, Venice, Museo Archeologico Nazionale. Originally in the Zulian collection, it was taken by the French in 1799 and returned in 1815. 174 11:28 Pagina 174 plessa operazione culmina nella «Statistica demaniale», in virtù della quale le direzioni provinciali compilano oltre 150 volumi. Sembrano pertinenti le parole delle Confessioni di Nievo: «Prima che la statistica aprisse i suoi registri, ciascun paese credeva d’essere quello che avrebbe voluto essere». Alla ricognizione farà seguito, dalla fine del terzo decennio, un’altra ondata di concessioni in deposito, aste e trasferimenti a titolo oneroso. In fondi del Governo o della Direzione del Demanio, possiamo tuttora individuare i relativi atti e «processi verbali», oltre a rintracciare qualche “sospensiva” giunta in extremis a salvare da imminenti vendite: come quella presentata il 20 novembre 1822 dalla Presidenza dell’Accademia e dal segretario Diedo, allorché, «col rossore di parer tarda, ma non col rimorso di esserlo, accompagna [...] la statistica dei capi d’arte, che in seguito ai più accurati riconoscimenti crederebbe di eccepire pel loro merito dalle vendite», a seguito di ulteriori ispezioni e «nuove scoperte», tanto che «ove per avventura fosse stato concepito qualche progetto di vendita, che ferisse le cose enunziate e descritte come rare», si chiede di «sospendere o rievocare le incamminate disposizioni». Y Le alienazioni aumentano nel 1833-1837, e nel successivo biennio l’Intendenza di Finanza e il Magistrato Camerale sollecitano una campagna per «l’apprezzamento dei quadri esistenti nei depositi demaniali», tale da fornire un nuovo elenco e aggiornare il «prospetto generale» di tutte le province; mentre si moltiplicano le concessioni in deposito dal 1838, allorché l’imperatore Ferdinando cinge la Corona ferrea a Milano (all’indomani dell’autorizzazione del 25 febbraio 1837 alla società per la ferrovia Venezia-Milano, la “Ferdinandea”). Tra gli Allegati governativi, si conserva anche la «sovrana risoluzione» dell’agosto 1838, secondo cui «meno che i quadri di questo deposito demaniali designati per le Gallerie di Vienna, gli altri di prima categoria sien distribuiti a chiese e pubblici istituti, quelli poi della seconda sien venduti». Una commissione stila due liste: una per le opere «di pregio» da conservare, l’altra relativa a quelle vendibili; in rosso, enumera i dipinti alienabili e senza valore, in nero i «disponibili». Nel 1847, l’Intendenza di Finanza elenca nei depositi 504 dipinti in 10 lotti destinati all’asta, per far spazio al “Congresso dei Dotti” (e poco prima, 15 gennaio 1846, si inaugura il ponte fer- 22-07-2009 12. Leopoldo Cicognara e Bartolomeo Gamba, Omaggio delle Provincie venete alla Maestà di Carolina Augusta Imperatrice d’Austria, Venezia, dalla Tipografia di Alvisopoli, 1818; frontespizio e particolare del testo, con l’incisione della Polymnia di Canova. Leopoldo Cicognara and Bartolomeo Gamba, Tribute by the Venetian Provinces to Her Majesty Caroline Augusta, Empress of Austria, Venice, from the Alvisopoli print shop, 1818; frontispiece and detail of text, with engraving showing Canova’s Polymnia. 11:28 Pagina 175 roviario sulla laguna). Nel 1851, un dispaccio da Vienna notifica la richiesta dell’arcivescovo di Leopoli di quadri da inviare da Venezia alle chiese della Bucovina: opere di Palma, Tintoretto, Ricci e Tiepolo partono così per i confini dell’impero. Y La macchina burocratica austriaca (che a Venezia nel 1827 conta 3.306 impiegati) rivela singolari “sfasature”. Le riscontriamo pure nei documenti archivistici relativi al trasporto a San Giovanni Evangelista dei circa 5.000 o 6.000 quadri demaniali esistenti nel locale della Salute, «onde sgombrarlo ad uso militare». L’operazione risponde alle ordinanze della Direzione del Demanio del 19 e 24 ottobre 1815. Il 14 dicembre, si presenta la «specifica del travaglio fatto e della spesa» di 362.744 lire, «compresa la mezza diaria di L. 3.07» (per 7 giorni di straordinario) richiesta dall’incaricato Pasquali, che si avvale della consulenza di Baldissini e dell’impiego di operai alla giornata «capaci nel maneggio dei quadri». Pasquali dettaglia il trasporto, dal 16 novembre al 9 dicembre, e ne commenta l’«economia» nonostante le avversità: «In particolare il longo viaggio dalle camere di deposito del locale della Salute a quelle dell’altro di San Giovanni Evangelista, la difficoltà dei ponti, che o per la sua naturale bassezza o per l’escrescenza dell’acqua obbligò a tenere bassi i carichi, ed infine la brevità delle giornate nella presente stagione, e la sua incostanza», fra i «tanti motivi, che produsse anco la molteplicità della manodopera»; e si richiede il pagamento per i «tanti mercenari». Intercettiamo però un documento datato l’indomani, 15 dicembre 1815, con le conclusioni di un consigliere, che, visitati «i locali riservienti per le caserme militari» giudica «non essere stato trovato necessario a tale oggetto quello della Salute. Perciò cessa il motivo del trasporto di quadri ivi esistenti». Il 19 dicembre 1815, le autorità annotano: «Prima che giungesse il dispaccio 15 corrente [...] sospensivo del trasporto dei quadri demaniali dal locale della Salute, era giunto al protocollo di questa direzione il rapporto di codesto economo Pasquali 14 detto [...] con cui perveniva che il trasporto medesimo era già compiuto». L’organizzazione veneziana si era dimostrata più efficiente di quella austriaca. l’indagine 0020.saggi.qxd 175 sotto la dominazione austriaca esiste già una “banda del buco” 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 176 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 177 a “hole-in-the-wall gang” under austrian domination “sell, whatever it costs”: 5000 paintings disappear, horses and lion return to venice research 0020.saggi.qxd Rosella Lauber 13. Joseph Mallord William Turner, Il Canal Grande, Venezia, 1835, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Joseph Mallord William Turner, The Grand Canal, Venice, 1835, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 14. Joseph Mallord William Turner, Approdo a Venezia, 1844, Washington, National Gallery of Art, Andrew W. Mellon Collection. Joseph Mallord William Turner, Approach to Venice, 1844, Washington, National Gallery of Art, Andrew W Mellon Collection. Y What would have happened if the Parisian Salon had refused to accept the works it did and the works by Cézanne, Pissarro and Courbet, or works such as Whistler’s Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl or Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, had been cut up into canvas rags or firewood? Fortunately, when in 1863 the Paris commission excluded 3,000 of the 5,000 works submitted, Napoleon iii ordered that the Salon des Refusés be opened. And it was here that, amidst Zola’s admiration and a ridiculing general public, the ground was laid for the first Impressionist exhibition of 1874, where Monet presented his epoch-defining Impression, soleil levant. What had happened in Venice a few decades earlier, under the “second Austrian domination”, and specifically in 1821, however, was that thousands of “rejected paintings” were converted into canvas and firewood. An important event that we will be reconstructing through documents and new archival discoveries. Y Francis i of Austria (fig. 2) urged no such Salon des Refusés in Venice for the more than 3,000 paintings deemed to be “absolute rejects” by a commission asked to examine about 5,000 paintings from Venice and the Veneto and held in the government’s deposits after the Napoleonic suppression. The special jury was convoked by the president of the Accademia delle Belle Arti, Leopoldo Cicognara (fig. 3), included the painters and professors “Liberal Cozza, Lattanzio Querena, Antonio [sic] Borsato”, and was directed by the acting secretary, the architect Antonio Diedo. The paintings were examined between May 29 and July 18, 1817, and their fate was determined by government decrees dated March 21 and April 29, 1817, according to which paintings deemed to be “absolute rejects” would be “sold in public auction”. In point of actual fact, they would “all be washed clean before being sold, considering that selling those paintings as plain canvases will perhaps be of as much advantage as selling them as pictures”. It was also thought “beseeming that this should be put to the vote” of the President of the Accademia, in that the 177 a “hole-in-the-wall gang” under austrian domination 0020.saggi.qxd 178 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 178 whole affair “besides being of interest to the [state coffers] is also important in preventing the deterioration of the Fine Arts”. Along with 200 publicly owned paintings considered “worthy” of conservation, selected by Professor Baldissini and approved for removal to Sant’Apollinare so that they could be “arranged for public or private use”, 500 other works were considered “commendable” by the commission. The “almost infinite mass of discarded works” were set aside for alienation “to our utmost advantage”. The “reserve choice” paintings were placed in three categories: paintings for the Accademia (rarities by “historical brushes”); those destined for churches (large and mediumsized, well preserved, of “good brush” and quality); those for sale (large and small, “of good brush and praiseworthy method”, which, if restored, might be considered of greater value, in order to find “a happier and more useful outcome in the commercial sphere, inspiring both the amateur collector and speculator”). On May 18, 1817, following academic evaluation and in order to avoid the “risk of infecting the market with bad paintings dishonouring the pictorial arts”, it was deliberated that the discarded paintings would be washed clean “and then put to auction as plain canvas”, to the “possible greater advantage of the state coffers”. Y Instead of washing the paintings clean, considered “an immensely demanding and costly undertaking”, what was finally approved as more “convenient” was a project presented by the administrator Antonio Pasquali on August 9, 1817, “whereby the depicted elements of the discarded pieces will be destroyed and the canvases and wooden frames sold”. This entailed “cancelling the depicted scene with a strong slicker..., or breaking the painting along its most deformed parts. Each of these expedients to be deployed according to the quality of the painting, which shall firstly be removed from its frame or soaza, will destroy the depiction and conserve the canvas in its best state”, which, once dried, could be sold for a profit, to which must be added “the other profits that can be extracted from the wood. As for paintings on wood, the depicted element shall be removed through scrubbing, making it suitable for firewood”. Pasquali gives a detailed rundown of the procedure: “Firstly completely separate the wood from the canvas” and “then cancel from that canvas all relevant signs of Painting in the manner described above, and finally destroy the wooden frame by cutting it into pieces for burning”. 22-07-2009 15a e 15b. La partenza dei cavalli nel 1797 e il loro ritorno nel 1815, incisioni. The quadriga leaving in 1797, and brought back in 1815, engravings. 11:28 Pagina 179 Pasquali proposed the following: “This Superior shall have the complaisance to decide if the mass of rejected paintings shall be identified in a solely numerical list or distinctly indicating corporation and provenance, which procedure shall be carried out at the moment when the wood shall be removed from the canvas”. The authorities back the “execution of the plan”, adding that “it is felt that it may be useless to keep a list of the paintings to be destroyed”. What’s more, it is rendered illegal to sell the rejected paintings to private subjects or to ‘repaint’ these “for other uses”, such as decorations for rooms (which would have been very difficult to enforce), in order to stop these paintings from being put back on the market. Y The government confirmed the public auction, which was to follow the “destruction” of all figurative signs in the works considered to be “of no painterly worth” so that they could be transformed into fabric and wood. On November 22, 1817, Pasquali presented the list of goods to be auctioned in nine points, where he informed the public that “canvas and wood are visible for aspiring purchasers at the former Scuola di San Giovanni Evangelista”, and that the dealing would begin after “a survey of the value of the effects”. On January 10, 1818, it was indicated that “the auction shall open at the value of one thousand two hundred lire”, even if Pasquali confessed that the “not perfect analysis... of the goods may perhaps have led to some doubts”. Y The auction was set for November 29, 1821, in the former Scuola di San Giovanni Evangelista. In the meanwhile, in compliance with the act dated May 26, 1820, “paintings of superior artistry and commemorating events of the homeland” (i.e. the paintings by Bellini, Mansueti, Carpaccio, Bastiani and Diana) were to be removed from the walls and consigned to the Accademia (fig. 4). In only one day, the venue was emptied of those thousand odd “canvases, frames and discarded pieces of wood” alienated in 1821 for the modest sum of 1,031 lire, as certified now by “verbal minutes” dated January 28, 1822, and undersigned by Pasquali and the winner of the auction. The winning bidder was invited to deposit “the offered price of 1,031 lire” and to proceed with “clearing of the premises” without in any way damaging them, as specified in the act dated January 11, 1822, which followed the “superior approval” which had been issued via a despatch dated December 27. The buyer arrived on January 17 so that he could be issued his permission to remove the objects in question, which was research 0020.saggi.qxd 179 a “hole-in-the-wall gang” under austrian domination 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 16. Giuseppe Borsato, L’imperatore e l’imperatrice d’Austria in visita alla sala canoviana di palazzo Treves, Venezia, collezione Treves de’ Bonfili. Giuseppe Borsato, The Emperor and Empress of Austria visiting the Canova room at Palazzo Treves, Venice, Treves de’ Bonfili collection. 180 11:28 Pagina 180 granted when he paid all sums due, minus the “twenty thalers” he had originally given as a deposit. His signature can be made out at the bottom of the document: “Nicholò Brazzoduro”. Y The same name can be found in other rare registers (up to now thought to be lost) that certify “Buyers of movable property, and paintings confiscated from the suppressed religious corporations”. There are also balance sheets from 1811 referring to Niccolò Brazzoduro for a total of 1,021 lire: on February 18, there is a ledger entry for the outlay of 550 lire “for the purchase of effects from the suppressed monastery of Santa Giustina”; on June 29, there is another entry for 471 lire “for similar, from the suppressed monastery of San Mattia on Murano”. These new archival sources add to the profile of Brazzoduro that we have already in part delineated. Second-hand dealer and building contractor, Brazzoduro bought the church of the Servi, but for its building material (and, in fact, by 1821 “it had all but been razed to the ground”). On April 20, 1807, he won a bid (for 364 lire) for 20 rails from the Santa Croce altar on the Giudecca; on December 31, he purchased books from the San Giorgio library. And again, on March 12, 1809, he bought the organ from the church of San Giovanni di Malta and the screen from the choir in the church of Santi Marco e Andrea on Murano, “with worn-out gold... weighing 426 pounds for 76,291 Italian lire”. Y As early as 1830, the alienations, including the sensational 1821 alienation, were raising quite a few questions. There are, in fact, very interesting records in a set of hitherto unknown documents dedicated to finding out “what happened to two paintings by Titian and Cima, once belonging to private owners” which left the Accademia and were later found, “the former at the home of the widow of the merchant and painter Baldissini, and the latter at the home of a certain Bortolo Giraldon” (that is the Deposition, Moscow, Pushkin Museum). An act from early February 1830 informs us that the Titian painting had gone “from Baldissini to Bortolo Adami, who currently owns it and 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 181 who declares that he bought it from that family, as per the said testimony made following an ‘invitation’ to the Police commissioner at Cannaregio”. Names of painters and/or buyers are thus intertwined (and that of Adami also appears in the rediscovered Buyers Register). One of the most important finds in the same batch of documents is a police interrogation dated April 19, 1830, aiming to establish “if under the now defunct Italic regime and at other times paintings were destroyed, with or without academic evaluation...” This was the question the Inspector for state property asked Pasquali, who had been identified as a person apprised of relevant information and “because of his role in the matter”. Information is demanded “regarding the period in which it was proposed, and regarding persons to whom it was proposed, that rejected paintings be destroyed, as was proposed by the current Government, and later undertaken through the sale of resulting canvases in the year 1821”; all the more so considering that nobody truly knew “that under the former Government there had been any destruction of paintings, while the acts... only indicate that after the choices made by Edwards and Professors Appiani and Fumagalli the only order given or pressed upon others was to sell at any cost”. Pasquali replied on April 30: “The real destruction of the paintings and the sale of canvases and wood took place under the current Government”. He then goes on to give details on how it was undertaken, confirming once more that never had any “destruction of Paintings taken place under the former Regime”, mainly but not only because it was “far from... not infecting the market with rejected paintings”, rather preferring to sell even the most “revolting rejects. See what has happened on several occasions during auctions of paintings”. Y In the meanwhile, goods continued to be sent to the state storehouses. Whence they sometimes also disappeared, it must be said, but not because the authorities had ordered it. Sometimes there were “art thefts”, the trial transcripts for which point now to fascinating dynamics. On May 4, 1827, the Government Presiding Committee received an urgent convocation for Pasquali, “following notification from the Head Police Commissioner of San Polo”, at the “deposit for paintings and other objects belonging to the state” at San Giovanni Evangelista. Pasquali had been called “to undertake an inspection following the report of a theft”. It had in fact been noted that “from a window just above research 0020.saggi.qxd 181 a “hole-in-the-wall gang” under austrian domination 0020.saggi.qxd 182 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 182 a small private vegetable garden scoundrels had entered the building by lifting a large iron grille over said window, and then removed copperware, glassware and quite a bit of hardware from the premises”. On May 5, a commission arrived “to carry out, inventory at the ready, a tally of the paintings and effects in the depot”: according to their reckoning, 10 paintings were missing, along with “six bronze mascarons taken from the internal doors of the premises”. The criminal tribunal then proceeded with “its Inquiry, but without hard proof or suspects regarding the crime”; from the testimony given, the only thing that emerged was “a large iron object known as a leva left behind by the criminals”. The documents contain a list of the stolen works, including their provenance: the churches of Santi Giovanni e Paolo, San Giorgio Maggiore and Santa Lucia, the Scuola dei Mercanti dell’Orto, the monastery of the Dimesse di Veronica; Sagredo “Commissaria” was missing not only a Veronica, but also a Saint with Little Angels; an oil on wood depicting a Redeemer was also missing, but not the frame; and the only thing left of a canvas depicting Jesus Adored by His Mother and Other Pious Followers was its stretcher frame. Y On September 15, 1827, the Government Presiding Committee was informed of another theft at San Giovanni Evangelista, where all the security measures had been thwarted, including the “night patrols” and the “numerous satellizio”, i.e. plain clothes agents from the “satellites” or civil police guard (according to statistics, there were 183 of these that year). Pasquali’s report provides details about the “patrolling of the premises at 5 o’clock in the afternoon” due to suspicions that there might be “new thefts”. An initial inspection revealed no signs of entry, not even on reaching the upstairs hall via the Codussi staircase (fig. 5). However, “wanting to ascertain whether the entrance that leads to the roof via a secret staircase within the main wall of the hall had ever been opened, and the door to which was hidden by paintings hanging on the wall, it was noticed that one of these paintings was missing, and all that remained was the frame. Hence the conviction that the ill-intentioned had in fact broken in”. The inspection was repeated, and “the door was open which from the large hall leads to the two rooms where the altar known as the Cross altar can be found, which door was closed via a chain from within”. On entering the second room behind the altar, they found that “a large painting on wood had been removed 22-07-2009 17. Festa notturna sulla Piazzetta in onore di Francesco I d’Austria, Venezia, collezione privata. Night Feast in the Piazzetta in Honour of Francis I of Austria, Venice, private collection. 11:28 Pagina 183 from its original lodging, and missing which painting we were much surprised to find an opening in the wall which could not be seen if the painting were hanging where it should. This hole is the same as the one that had been made the other time, and found during an inspection undertaken on May 5, which hole on that occasion had served to allow entrance into the two following rooms and the attic”. Once they discovered the modus operandi used by the forebears of the “hole-in-the-wall gang”, they finally found, “in the attic above the room with the church altar, suspicious evidence from a low light fixture”, recognised as the “place of entry, as the roof tiles had evidently been tampered with, and were discovered lying next to a so-called sgaruccio with a serried handle”. They also tried to understand “whether they had come from land or water to climb onto the roof to get into the attic”. Interrogations in the neighbourhood revealed suspicious movement around sunset, noises and even “persons who fell into the water” “in the local rio” as well as approaching boats with ladders. The same “scoundrels” who had come in spring, “familiar with the premises”, had therefore returned, doubling their booty. Amongst the documents we discover also a “list of the found paintings missing” in the inspections of September 17-19, 1827: it contains 21 stolen works, including “The Presentation of Mary at the Temple by Peranda”, i.e. Sante Peranda. There were fragments of wood, or the “entire frame”, and “two of the existing paintings were stripped of their respective gold frames”. Y Besides the police force and bureaucratic centralisation, the Habsburg government in Venice also put into place a complex and long term cultural policy during the “second Austrian domination” (1814-48) and the third (1849-66), interrupted by the events of 1848-49, both of which followed the first Austrian government (1798-1805) following the Treaty of Campoformio. This was followed by a further 8 years of French rule under the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy (1806-14), initiated by research 0020.saggi.qxd 183 a “hole-in-the-wall gang” under austrian domination 0020.saggi.qxd 184 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 184 Napoleon’s suppression of religious corporations, monasteries, churches, confraternities and schools between 1806 and 1810, and the ensuing confiscation of their property. Artistic masterpieces were hoarded and catalogued in deposits such as the former Scuola di San Giovanni Evangelista and the former Commenda di Malta. The better works were sent to France or Lombardy, and hundreds were given to the new art collections at the fine arts academies, including Venice (in the refurbished Carità) and Milan (selected for Brera by the commissioners Appiani and Fumagalli). Works “not singled out for the Crown” were marked for sale; there were endless public auctions, devalued or deserted because of rampant inflation and the economic crisis. Y The transformation of the status of works of art imposed from above nonetheless merged with a latent progressive movement of changes in ownership, and was further scaled down after measures such as the rationalisation of public finances and the reduction of manomorta, or mortmain: deliberated as early as 1768 by the Venetian Senate and so far-reaching they determined a massive circulation of art works, including amongst merchants and collectors. 18th- and 19th-century interventions in the Veneto’s artistic heritage and state-owned properties (see indepth studies by Spiazzi and Schiavon, Zorzi, Olivato, Pavanello and Romanelli) show just how poised things were between continuity and innovation. Austrians in Venice were sensitive towards emblematic works. After the fall of Napoleon at the Congress of Vienna, the ex Dominante was given back codices and art works, particularly from the French, but certainly not from Brera (fig. 6) or the Lombardy churches. On the inauguration of the second Austrian government, and after the institution of the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia on April 7, 1815, there was a triumphal sign of restoration amongst the gondolas and “stones of Venice”: the Habsburg eagle returned to Venice, accompanied by the horses and lion of St Mark. Y In fact, 18 years previously, in December 1797, the French had also removed the bronze quadriga from St Mark’s (fig. 7), which was then placed at the Arc du Triomphe du Carrousel by Napoleon. When the Austrian victors decided to remove the horses from the triumphal quadriga towering between the Louvre and the Tuileries, they decided to do so under cover of darkness and protected by the military for fear of revolts. And the military was also used to escort the convoy when it left Paris on 22-07-2009 18. Eugenio Bosa e Andrea Tosini, Allegoria in occasione della concessione a Venezia dell’estensione del Porto Franco, incisione. Eugenio Bosa and Andrea Tosini, Allegory on the Occasion of the Concession of an Extension of the Free Port to Venice, engraving. 11:28 Pagina 185 October 17, 1815, laden with works on their way back to Italy and the Vatican, above all thanks to Canova (fig. 8). Thanks to the artist and to Schwarzenberg, and as decided by the emperor, on December 13, 1815, the four horses, the symbolic identity of Venice, arrived in St Mark’s basin (fig. 15), greeted by the deafening roar of a “universal hurray”. Y The horses were returned in the presence of Francis i, Prince Metternich and other dignitaries. Vincenzo Chilone immortalised the moment in the painting now in the Treves de’ Bonfili collection (fig. 9); a capriccio by Canaletto (fig. 1) seems to be based on Canova’s project to place the horses on tall plinths in front of the Ducal Palace. Cicognara dedicated a historical narrative to the event, and in a public lecture he celebrated the return, thanks to the Austrians, of works “held by the Seine”, including St Mark’s lion (fig. 10) and the Jove (fig. 11). In 1817, Cicognara used the 10,000 sequin tribute imposed by the government for Francis i’s fourth marriage to Caroline Augusta of Bavaria to commission works from local artists. The so-called Homage of the Veneto Provinces (fig. 12) thus made its way to Vienna: furniture, paintings, sculptures (foremost of which was Canova’s Polymnia, which had been exhibited at the Accademia alongside Titian’s Assumption of the Virgin, defined “the most beautiful painting in the world”). Y In the meanwhile, private and religious buildings were being demolished or converted into taverns, mills, warehouses, barracks and “penal baths”; theatres were shut down (in 1824, the theatre of San Moisè was transformed into a carpentry workshop); monuments and altars were being dismantled for building materials and stone, especially between 1813 and 1820. Venice was still “a city from the Thousand and One Nights”, as Prince Metternich wrote to his wife on July 10, 1817, with the Giudecca and Grand Canals “literally covered with gondolas” (fig. 13), cafés open and people up and about till dawn; but, notes the princess Mélanie Metternich in her diary when she arrived from Fusina in September, 1838, the “magnificent spectacle” offered to those research 0020.saggi.qxd 185 a “hole-in-the-wall gang” under austrian domination 0020.saggi.qxd 186 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 186 arriving in the city (fig. 14) is offset by the sadness of buildings falling to pieces. Public works for the restoration of buildings and bridges would start in the 1820s. From the Ghetto, whose gates had been removed in 1797, Jewish families with a great deal of economic clout began to purchase real estate, especially considering there were no more limitations on property ownership. They initially extended to the immediate neighbourhood, then the Rialto, St Mark’s and along the Grand Canal. Ca’ d’Oro, a “building in parlous state”, was bought by Moisè Conegliano, then passed on to Prince Trubetzkoi, who in turn gave it to the ballerina Maria Taglioni. In 1827, Isacco and Jacopo Treves de’ Bonfili, both bankers, bought Palazzo Barozzi Emo on the rio di San Moisè, where a scenographic venue was created for Canova’s Hector and Ajax, bought for 55,000 lire (fig. 16). Y Massive sell-offs of real estate and other goods had for some time been more common thanks to economic problems aggravated by Napoleonic requisitions and the 1813-1814 blockade, and the subsequent crisis, with its epidemics, floods and famine. The situation remained critical for quite some time, and in 1825 Francis i received a report by the patriarch Pyrker (a patron of Viennese artists in Venice, but also the promoter, fortunately ignored, of a movement for the destruction of the St Mark iconostasis) which contained comparisons with 1797 and was considered so alarming it was reported in the Times and Journal des Débats. The 1827 numbers provided further confirmation of the gravity of the situation: the number of shopkeepers had dropped from 10,884 to 3,628; artisans from 6,200 to 2,442; Arsenale workers from 3,302 to 773; traghetto gondoliers (those who ferried people across canals) from 1,088 to 607, and other gondoliers from 2,854 to 297; the number of inhabitants had dropped from 136,000 to 100,556 (40,764 of whom required welfare benefits of some kind). The emperor, “to help the good Venetians” who demonstrated great support for him (fig. 17), pressed for a solution; Pyrker invoked an extension of the Free Port, which was conceded on February 20, 1829 (fig. 18). In the meanwhile, private owners continued to sell coins, medals, paintings and sculptures, along with entire collections and libraries, often to foreigners, and even Austrians. Y The reasons for this state of affairs can be found as early as the closing decades of the Serenissima, and are clearly laid out in the letters of Apostolo Zen, one of the founders of the Giornale de’ let- 22-07-2009 19. Rilievo con leonessa che allatta i cuccioli, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum; già a Venezia, collezione Grimani. Relief with Lioness Suckling Her Cubs, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, originally in Venice, Grimani collection. 11:28 Pagina 187 terati d’Italia and Caesarean poet to the Viennese court: if on the one hand Zeno decries that “bit by bit Italy is losing its best...; but this is not surprising, because money, taste and study are lacking”, he nonetheless sold his own impressive coin collection to “a German” in 1748. Anton Maria Zanetti, however, received gems and old cameos in Vienna in exchange for advice about the prince of Liechtenstein’s collection, which would eventually contain, via the antiques dealer Guggenheim, the two reliefs by Palestrina now at the Kunsthistorisches Museum (fig. 19) and owned by the Grimanis until the 19th century. Other marbles from this collection (admired as late as 1822 by visitors such as Thiersch) were put on sale in 1831 by the antiques dealer Sanquirico, and other pieces, offered in vain by Michele Grimani to Francis i, were bought by merchants such as Weber, Richetti and Pagliaro and eventually reached important German and Austrian clients. Y We can trace a progressively larger flow of works from Venetian collections to those in Vienna, as in the case of the Attic reliefs, which went from the TrevisanSuarez museum to the magnificent Obizzi al Catajo (Battaglia Terme, not far from Padua) collection, which then went in its entirety to Vienna. And it was here, in the early 19th century, that part of the Garzoni collection ended up (other elements ended up in Constantinople). In about 1820, Girolamo Silvio Martinengo offered his museum to the Austrian government which, having received the estimate, declined the count’s offer, which the widow Elisabetta Michiel then made, again in vain. The collection was finally bought in 1836 also by the merchant Fontana from Trieste before the contents were sold off throughout Europe. In 1821, pieces from Domenico Almorò Tiepolo’s collection of medals and coins were sold to Francis i. In 1805, the emperor had bought, for Venice’s Accademia, plaster casts and models from the Farsetti collection, including terracotta research 0020.saggi.qxd 187 a “hole-in-the-wall gang” under austrian domination 0020.saggi.qxd 188 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 188 models by Bernini. There is an emblematic entry in Cicogna’s unpublished Diari dated February 3, 1817, when Antonio di Giacomo Nani undersigned the sale to Francis i of the entire collection at San Trovaso, “one of our most beautiful museums, which must now leave for Vienna”, for “90,000 gold ongari”, to be paid in instalments “because Nani refused to accept state-owned land or allotments in Austria. Thank goodness the collection is leaving in its entirety”. Cicogna then emended this on April 7, 1817: “Nani’s museum is not going to be sold any more, and will remain here, if it is not devoured by his creditors”, who were threatening “to divest him of the best and the good”. The news is also given in Fapanni’s annotations (see VeneziAltrove 2005), who was very critical of the “Reverend Antiques Dealers” and “honourable Brokers and wheeler dealers”, who “would even sell St Mark’s basilica, if they could, to foreigners”. Francis i was not in favour of exporting art objects from Venice, despite the constant offers from collectors: often, the very descendents of the important houses described in Barbaro’s Arbori, the most trustworthy codex of which is now in Vienna among the volumes that were once Foscarini’s and were confiscated by tax inspectors from Giacomo Foscarini, greatgrandson of the doge Marco Foscarini. Y Austrian measures regarding art in Venice were articulated according to the principles of safeguarding the city’s heritage and keeping checks on the art market. From 1816, 14 of the best pieces were sent to Vienna. In Vienna in June 1838, the prince of Czernin received 18 cases, with 76 paintings for the Belvedere; in August, via Metternich, a further 26 packages arrived containing 85 paintings for the Akademie der Bildenden Künste (given back after 1919). Auctions and sales became more common in Venice once more, often overseen by representatives of the Accademia, whom the painter Odorico Politi, according to Cicogna’s Diari on March 19, 1819, accused of monopolising “paintings from the public domain that are at the Commenda di Malta, and that are being sold underhandedly and exchanged 22-07-2009 20. Leonardo da Vinci, Le proporzioni umane secondo Vitruvio, Venezia, Gallerie dell’Accademia, Gabinetto dei Disegni e Stampe; già in collezione Bossi, a Milano, e venduto a Luigi Celotti, nel 1822 è acquistato per le Gallerie da Francesco i, su sollecitazione di Leopoldo Cicognara. Leonardo da Vinci, Vitruvian Man, Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia, Gabinetto dei Disegni e Stampe. The work was originally in the Bossi collection, Milan, and was sold to Luigi Celotti; in 1822, it was bought for Francis i’s Galleries, on the suggestion of Leopoldo Cicognara. 11:28 Pagina 189 without government permission, damaging our rarities and guaranteeing great wealth to those involved”. That professors were involved in the market, even the legitimate market, is borne out by other, contemporary collections of letters. Thus on July 3, 1802, Ferdinando Tonioli suggested to Canova the name of “Baldicini”, i.e. Giuseppe Baldissini, son of the academic Nicolò Baldissini, as one of the “Painting Merchants” gifted with “exhaustive knowledge and a certain amount of probity”. Y The emperor also bought works for the Venetian Accademia, amongst which drawings from the Quarenghi collection in 1824 (see VeneziAltrove 2004), and others from the Bossi collection in 1822 (including Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, fig. 20) on the advice of Cicognara. The refurbished Rialto Fabbriche housed the new legal courts, moved from the Ducal Palace in a bid to avoid another fire like the one that had destroyed Ca’ Grande dei Corner in 1817, and especially after the outbreak of a fire that had threatened to burn down the hall of the Maggior Consiglio in 1821 (about 20 years later, on December 13, 1836, La Fenice would be destroyed by fire only to be immediately rebuilt and reopened on December 26, 1837). After 1822, as can be seen from a Memoria by Corniani degli Algarotti dated March 7, 1827, “many pieces have arrived [at the depot of the former Commenda di Malta] from Palazzo Grimani now the General Post Office, and others from Palazzo Corner, currently the Offices of the Royal Imperial Delegation”. Since 1817, the State Archives had been housed in the Frari convent. In the adjacent church, before the monument to Titian paid for by the emperor, the monument to Canova had been inaugurated in 1827 (he had died five years before at the home of the owner of the Caffè Florian). Among the financial backers for the cenotaph, promoted by Cicognara (fig. 21), pride of place was occupied by Francis i and his wife, along with the prime minister of England, kings, bankers and men of culture such as Byron, Quatremère de Quincy and Alessandro Volta. And any church or vestry that asked was granted goods conceded by the “goodness of the Government for simple use and in order to be well looked after”. Y In 1817, it was deemed urgent to draw up a catalogue of the artistic heritage and properties that still belonged to the state. The complex operation culminated in the “public statistics”, for which the provincial directorships compiled more than 150 volumes. As Nievo wrote in his Confessioni: “Before statistics opened research 0020.saggi.qxd 189 a “hole-in-the-wall gang” under austrian domination 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 21. Giuseppe Borsato, Leopoldo Cicognara illustra il monumento di Canova ai Frari, Parigi, Musée Marmottan. Giuseppe Borsato, Leopoldo Cicognara Explaining the Monument to Canova at the Frari, Paris, Musée Marmottan. 190 11:28 Pagina 190 her books, each country thought it was what it wanted to be”. This census was followed, in the late 1830s, by another wave of concessions, auctions and onerous transfers. In government or Demanio deposits, we can still find the acts and minutes, as well as retrace the odd “adjournment” that arrived at the last minute to save pieces from imminent sale. One such “adjournment” was presented on November 20, 1822, by the Accademia presidency and the secretary Diedo, when, following another cataloguing of art works, “new discoveries” led to the conclusion that “should, peradventure, any sale project be devised that may harm the things listed and described as rare” then any standing disposition to sell these objects should be “suspended or revoked”. Y Alienations increased in 1833-37, and in the following two years the revenue offices and the chamber magistrature pressed for a campaign for the “appraisal of paintings currently held in the state deposits” so as to provide a new list and up-date the “general prospectus” for all the provinces. And deposit concessions also increased from 1838, when the emperor Ferdinand i of Austria received the Iron Crown in Milan (after the authorisation for the construction of the Milan-Venice railway line, known as the “Ferdinandea”, which was granted on February 23, 1837). Amongst these governmental Annexes, there is also the “sovereign resolution” from August 1838 that states that, “except for the paintings in this state deposit set aside for the Viennese galleries, the other first-class paintings shall be distributed to churches and public institutions; those which are deemed second-class shall be sold”. A special commission compiles two lists: one of the “valuable” works to be conserved, the other listing those works that were to be sold; those listed in red were considered worthless and could be alienated, while those in black were “available”. In 1847, the internal revenue offices listed 504 paintings in the various deposits, collated in 10 lots destined for auction and to make room for the “Congress of the Learned” (just after which, on January 15, 1846, the railway bridge over the lagoon was inaugurated). In 1851, a despatch from Vienna informed local government that the Archbishop of Lvov had requested that paintings be sent from Venice for the churches of the Bukovina district: works by Palma, Tintoretto, Ricci and Tiepolo were thus sent off to the very periphery of the empire. Y The Austrian bureaucratic machine (with its 3,306 employees in Venice alone in 1827), however, was not always perfectly con- 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 191 sistent. There are inconsistencies, for example, in the archival documents pertaining to the removal to San Giovanni Evangelista of about 5 or 6,000 government-owned paintings in the Salute, “so that it can be cleared for military use”. The operation was a direct consequence of the ordinance issued by the directorship of the Demanio, dated October 19 and 24, 1815. On December 14, Pasquali presented, via his representative, his “specifications of the work undertaken and the costs incurred” of 362,744 lire, “including the half travel allowance of 3.07 lire” (for 7 days’ overtime); Pasquali had availed himself of the consultancy of Baldissini and a host of day labourers “able to manage paintings”. Pasquali provides details of the transport, from November 16 to December 9, and comments on how expenditure had been kept down despite the adversities: “In particular, the long voyage from the deposit at the Salute to the other at San Giovanni Evangelista, the difficulty of negotiating the bridges which, either because they were naturally low-slung or because the tides were particularly high, forced us to keep our loads rather small, and finally the scant hours of sunlight in the current season and the inclemency of the weather”, one of the “many reasons that also led to the large numbers of workers”, and payment is also requested for the “many mercenaries”. But we found out also another document, dated December 15, 1815, detailing the conclusions of a counsellor who, having visited “the premises reserved for the military barracks”, considers that “the premises at the Salute are not appropriate for this purpose. The reasons, therefore, for the transport of the painting herein contained are no longer viable”. On December 19, 1815, the authorities noted: “Before the arrival of the despatch dated December 15... suspending the transport of state-owned paintings from the premises of the Salute, our registry offices had received a report from the administrator Pasquali dated the 14th... in which he informed us that the transport of said paintings had already been undertaken”. Venetian organisation had shown itself to be more efficient than Austrian bureaucracy. research 0020.saggi.qxd 191 0020.saggi.qxd 22-07-2009 11:28 Pagina 192 Fotolito e impianti CTP Linotipia Saccuman & C. snc, Vicenza Stampato da La Grafica & Stampa editrice srl, Vicenza per conto di Marsilio Editori s.p.a. in Venezia ® edizione 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 anno 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013