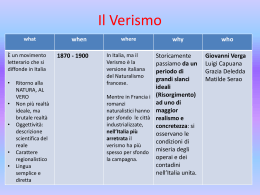

VERISM0

FROM

LITERATURE

TO

Matten Sansone

Ph. D.

University

of Edinburgh

1987

OPERA

ABSTRACT OF THESIS

The present study is mainly concerned with a comparative

analysis of the libretti

and the literary

sources of some Italian

operas

composed between 1890 and 1900, that is in the decade commonly idenRusticana and closed by

tified

as 'veristic',

opened by Cavalleria

Tosca.

It also attempts a reassessment of the connections

between

literary

verismo and the musical theatre

of the late nineteenth

century in Italy.

The controversial

of some 'veristic'

evaluation

operas has often

led to wrong assumptions concerning

the characteristics

of literary

While the positive

contributions

of the movement to the musiverismo.

have, on the whole, been overlooked,

cal theatre

major shortcomings

1890s,

in

the

such as excess and sensationalism

noticeable

operas

of

literature.

The essential

have been blamed on veristic

features

of

literary

adaptverismo could not, and did not, pass into any operatic

A comparative

of the source and the libretto

ation.

analysis

of MasCavalleria

Rusticana shows the limited

extent to which Verga's

cagni's

innovative

conception

was preserved in the musical transposition.

literary

The major figures of Italian

verismo, Giovanni Verga

and Luigi Capuana, happened to be personally involved in the adaptation of some works of their own for the musical theatre, namely La

The outcome

Lupa and I1 Mistero by the former, Malia by the latter.

partly because Verga

of the experiment was altogether disappointing,

to challenge the estaband Capuana were not able, nor indeed willing,

lished conventions of a versified

operatic text, partly for the modest

(P. Tasca, D. Monleone,

level of the composers who set their libretti

F. P. Frontini).

The prevailingly

literary

approach chosen in this study accounts

for the exclusion of Leoncavallo's

Pagliacci from a detailed textual

libretto

1.

Its

is

Chapter

in

though

the

to

analysis,

opera

referred

from

was written by the composer himself on the basis of recollections

his childhood.

On the other hand, the inclusion of a totally

neglectby the literary

source of

ed opera, Giordano's Mala Vita, is justified

(a play by Salvatore Di Giacomo).

the libretto

The analysis of a libretto

would not be exhaustive if it did not

This has not been

take into account the musical treatment of the text.

neglected in the examination of the operas selected for the present

Musical illustrations

from the vocal scores have been included

study.

sources and the libretti.

along with excerpts from the literary

CONTENTS

Pace

1

Introduction

Chapter 11.

2.

Towards a definition

of verismo in late

century Italian

opera

The offspring

Chapter 2-

of Mascagni's Cavalleria

The Verismo of Cavalleria

1.

From Verga's "Scene popolari"

2.

Gastaldon's

Rusticana

3.

Verga, Mascagni and the critics

Chapter 3-

School

Verismo and the Young Italian

Literary

nineteenthRusticana

4

20

31

Rusticana

to Mascagni's opera

Mala Pasqua! and Monleone's Cavalleria

31

49

62

76

Verga and Capuana as Librettists

Chronicle

Lupa:

La

and

4

76

1.

Puccini

2.

3.

The short story, the play and the libretto

of La Lupa

I1 Mistero by G. Verga, Giovanni and Domenico Monleone

109

4.

Malia by L. Capuana and Francesco Paolo Frontini

123

Chapter 4-

Salvatore

of an abortive

Di Giacomo and Neapolitan

project

Verismo

1.

The poet of colours

2.

Mala Vita by Nicola Daspuro and Umberto Giordano

Musical postcards from Naples: A Santa Lucia and

A Basso Porto

3.

and sounds

83

141

141

156

173

Conclusion

186

Notes

189

Bibliography

206

INTRODUCTION

The present study is mainly concerned with a comparative analyand the literary

operas

sis of the libretti

sources of some Italian

composed between 1890 and 1900, that is in the decade commonly idenas 'veristic',

opened by Cavalleria Rusticana and closed by

Tosca. It also attempts a reassessment of the connections between

literary

verismo and the musical theatre of the late nineteenth century in Italy.

tified

The controversial

evaluation of some operas, labelled as 'verihas often led to wrong assumptions concerning the characterisstic',

tics of literary

While the positive contributions

verismo.

of the

movement to the musical theatre

have, on the whole, been overlooked,

major shortcomings - such as excess and sensationalism - noticeable

in second-rate operas of the 1890s, have been blamed on veristic

litThe essential features of literary

erature.

verismo could not, and

did not, pass into any operatic adaptation of the 1890s. A comparative analysis of the source and the libretto

of Mascagni's Cavalleria

Rusticana shows the limited extent to which Verga's innovative concepwas preserved in the musical transposition.

The major figures of Italian

literary

verismo, Giovanni Verga

and Luigi Capuana, happened to be personally involved in the adaptation of some works of their own for the musical theatre, namely La

tion

Lupa and Il Mistero by the former, Malia by the latter.

The outcome

of the experiment was altogether disappointing,

partly because Verga

to challenge the estaband Capuana were not able, nor indeed willing,

lished conventions of a versified

operatic text, partly because of

the modest level of the composers who set their

0. Monleone, F. P. Frontini).

The prevailingly

for

the exclusion

textual

analysis,

libretti

(P. Tasca,

literary

approach chosen in this study accounts

of Ruggero Leoncavallo's Pagliacci from a detailed

though the opera is often referred to in Chapter 1.

paired with Cavalleria Rusticana as the best-known operas of

trend, Pagliacci has a libretto

the 'veristic'

written by the composer

from his childhood.

If a case were

himself and based on recollections

Usually

the libretto

to be made of 'verismo from opera to literature',

lgiacci should be classified

as a sensational feuilleton

with

1

of Paliterary

(the

pretensions

tics of verismo;

own aestheprologue with a statement of the author's

the old device of the play within

the play).

On the other

hand, the

Umberto Giordano's

opera,

inclusion

is justified

Mala Vita,

(a

libretto

the

play by Salvatore

of

comparison it makes with Cavalleria

ness to the original

text

and the

of a totally

neglected

veristic

by the literary

source

Di Giacomo) and the interesting

Rusticana

impact

as regards

the faithful-

the opera had on contemporary

audiences.

Some guidelines

have been followed

in setting

the limits

and ob-

jectives

of this study.

The analysis of a libretto

would not be exhaustive and critically reliable

if it did not take into account the musical treatment of

the text which is not only relevant for a comprehensive assessment of

in a comparative study of the literary

an opera but also instrumental

The ultimate classification

sources of a libretto.

of an opera is actually a problem of musical dramaturgy in which the literary

connections of the libretto

are of secondary importance.

dramatic shape, number

Linguistic

versification,

registers,

and casting of vocal roles, function and frequency of choral sections,

in a literary

text, the libmaterialize

elements which first

determining their best

retto; but the aesthetic and formal criteria

In the

arrangement belong to the conventions of the musical theatre.

are all

choice of subjects, different

trends, tastes and education

sheer expediency.

The practical,

factors interfere:

cultural

non-literary

influence,

of the public, the publisher's

business-like

approach of the composers of the

Young Italian

School in the choice of their libretti

is a sign of the

Verdi claimed that a composer should look askance when writtimes.

ing an opera: the reasons of art and the demands of the public were

Puccini, more cynically,

believed that:

to be equally considered.

'I1 faut frapper le public'.

Verdi lived and worked through the RiWhatever the subjects of his operas, we detect a solid

sorgimento.

A sneering court-jester

could

ethical code underlying his dramaturgy.

say to his daughter in the privacy of their home: 'Culto, famiglia,

a

/Il

in tel' Faith in God, the family and the

universo

mio

patria,

fatherland pertained to Rigoletto no less than to Rolando about to

fight

tion

Barbarossa at Legnano and entrusting

his wife with the educa'Digli ch'e sangue mio, /... /E dopo Dio la Patria/

of their child:

2

Gli apprendi a rispettar.

'

The composers of the Young Italian

math of the Risorgimento.

years of the fin-de-siecle

the new social

reality

They reached

crisis

which

School

their

of ethical

grew up in the after-

artistic

in the

maturity

and aesthetic

emerged from the political

In

values.

unification,

the function

'melodramma' as a unifying

of the nineteenth-century

cultural

and ideological

medium had come to an end.

In literature,

the iconoclastic

of

and regenerating

experience

the 'Scapigliatura'

by a number of contrasting

tendencies

was followed

providing

herence

ism,

did

cultural

to one or other

exoticism

not imply

influences,

Verdi

to young composers.

As for

aesthetics.

to Massenet and down to the drawing-room

production

ad-

decadentism,

symbolverismo,

in the last quarter

of the century,

ranged from Wagner to the French

of cultural

The occasional

of the trends

- which were rife

a commitment to their

they

wide spectrum

dictory

incentives

and musical

of the Young Italian

School

the musical

song style.

references

in variable

from

grand-opera,

Such a

had an impact

and often

on the

contra-

ways.

opera is therefore

a 'verismo' composer or a 'veristic'

An examinasimplifications.

no easy matter and may lead to arbitrary

tion of the connections between literary

verismo and late nineteenthcentury Italian

opera seems to be a step in the right direction.

Defining

3

Chapter 1

LITERARY VERISMO AND THE YOUNG ITALIAN SCHOOL

1.

Towards a definition

Italian

opera

The expression

tion

of verismo in late

'operatic

of a fundamental

verismo'

nineteenth-century

originated

work of the short-lived

from the associa-

veristic

theatre

Ver-

"Scene popolari

(1884)

Cavalleria

Rusticana

siciliane"

- with

Mascagni's

'melodramma' based on it.

The year 1890, when the opera

date of birth

was first

performed in Rome, was assumed as the official

ga's

was supposed to be the archetype.

of which Cavalleria

In the 1890s there was a limited

production

of operas based on veris-

of a new tendency

tic

and Mala Vita,

and a large number of

such as Pagliacci

In the course of the decade, however, literary

imitations.

subjects,

mediocre

verismo

ceased to be a source

for

of subjects

any major

opera.

So,

Iris,

Tosca,

when works such as La Wally, La Boheme, Andrea Chenier,

had to be accounted for, the problem of defining

a new compositional

style

on purely

grounds

musico-dramatic

Alternative

denominations

were suggested: 'naturalistic',

'of the Young School'.

cinian',

became crucial.

to the misleading 'operatic verismo'

'Puc'postverdian',

'late-romantic',

The last

one proved the most comprehensive and the least compromising as it is mainly based on a histoThe term 'School' should be understood as a convenrical criterion.

tional grouping of composers with different

trainings

and cultural

backgrounds and, indeed, with distinct

artistic

ni, Mascagni, Leoncavallo, Giordano, Franchetti,

Puccipersonalities:

Cilea and others.

born round the decade 1855-65 and, in their formative

years, were exposed to the same sort of national and foreign influences

(Ponchielli,

Verdi, Gounod, Massenet, Bizet, Wagner) which they assiThey were all

Puccini

for

been

has

made

case

milated

but

inclinations,

in terms of outstanding achievements and cultural

his stylistic

references are not all that far apart from the common

ground of the group.

in various

degrees.

A special

the operas of the

The established practice of categorizing

School according to whether the libretti

Young Italian

are derived

4

thematic,

from veristic

uistic

works or contain similar

led

laborious

has

to

elements,

ings.

The term first

with

the Young School

that

degrees

'verismo'

variable

of

exercise

evolution

is

Cavalleria

is

It

are still

at pains

to assess

to stress

necessary

as it

that

to connect

attempts

the

a literary

in opera with

features

and vocal

linked

composers or in different

hardly

pursuit

group-

unsatisfactory

has become so closely

in different

a frustrating

of new musical

and largely

some critics

by the same composer.

operas

this

used for

and ling-

structural

drive and

movement which, in the 1890s, had exhausted its innovative

tendencies

was losing ground to other contrasting

such as D'Annunzio's

decadentism and Fogazzaro's

in turning

Verga himself,

spiritualism.

his

short

1891-94,

story

moved away from the verismo

which eventually

essay "Verismo

interested

Puccini

in der Oper",

'Verismo

literature.

in veristic

they

which

from veristic

all

for

As Egon Voss states

It

should

is

ironical

be labelled

by either

rejected

a hybrid

in his

composers were not immediately

'1

School

in the years

Puccini,

of the 1880s and created

to set.

refused

sers of the Young Italian

verismo

a libretto

"La Lupa" into

the compo-

that

one term to set libretti

with

refusing

the uncongenial

nature of

works or pronouncing

CaMascagni's

Even

to

that movement to their

applied

art.

when

own

is not entirely

'operatic

the definition

satisfacverismo'

valleria,

derived

tory

for

play

on the musico-dramatic

two reasons:

firstly,

it

overstates

characteristics

the

impact

of Verga's

of the opera which was,

on the whole, less innovative than the "Scene popolari siciliane";

tendency

secondly, it does not accommodate the notion that a realistic

pre-existed to Mascagni's Cavalleria

and stemmed from the erosion of

the ideological

and musico-dramatic structures

of the romantic

dramma', irrespectively

of the veristic

movement in literature.

ever,

tents

the real problem is not so much one of denominations

and historical

perspectives.

'meloHow-

as of con-

Although literary

verismo is best represented by Southern Ita(Verga and Capuana), it was in Milan that the movelians and Sicilians

1870s.

in

It was partly the positive outcome of

the

originated

ment

the non-conformist,

movement which involved

subversive 'Scapigliatura'

The

in

Milan.

its

had

centre

and

painters, musicians, poets, critics

term 'Scapigliatura'

'boheme' by Cletto

was introduced

Arrighi

as a translation

of the French

in his novel La Scapigliatura

5

e it

6 feb-

braio

(Milano,

of the movement, illustratof manifesto

Leading

life

of young 'scapigliati'.

adventurous

1862),

ing the irregular,

a sort

Arrigo

the

the

poets

young

movement

were

of

members

Tranquillo

Cremona, the musician

Praga, the painter

critic

-close

Cameroni.

Felice

to the

presented

by the playwright

rana and the novelist

Igino

and Emilio

Franco Faccio,

the

were also

and the young Catalani

2

A Piedmontese section was re-

Ponchielli

'Scapigliatura'

Boito

circle.

Giuseppe Giacosa,

the poet Giovanni

Came-

Ugo Tarchetti.

The aspiration

to free themselves from cultural

provincialism,

an urgency to move beyond the extenuated romanticism of much secondto look outside Italy

rate literary

production led the 'scapigliati'

towards France, in particular,

and Germany. French naturalism and Zola

became major cultural

models introduced

references and authoritative

by the critical

writings of Cameroni and made widely accessible by the

Verga's arrival

of Emilio Treves.

open-minded publishing activity

Milan, in 1872, came at the right moment in his literary

career.

in

He

Cameroni.

In

Giacosa

the stimulating

Boito,

and

enwith

in

Italy,

Verga

tried

the

cultural

centre

most progressive

vironment of

subject matter

out his new style and began to deal with a different

His vefrom his early novels set in fashionable high-society

circles.

made friends

Sicihis

the

of

rural

ethical

world

of

popular,

rismo was a rediscovery

ly which he contemplated and described with the detachment and nostalgia

of a transplanted intellectual.

Verga's

feature

dominant

be

the

of

singled

out

as

may

stories and novels of the 1880s: restraint

of passion and emotion in

in

the portrayal of Sicilian

peasants and fishermen; formal restraint

Restraint

the elaboration of a terse, self-effacing,

sapid prose style which almost lets the story tell itself

and the characters speak their minds

in their own way. Sensationalism and excess are banished on principle.

Violence may occur in the form of murder and is set within the natural

is

it.

A

the short

the

example

community

good

of

which

endorses

ethics

in

Turiddu

Rusticana"

has

to

"Cavalleria

Alfio

challenge

where

story

Lu"La

kill

in

In

him

duel.

the

then

story,

next

a

rustic

public and

from

liberates

kills

Pina

the

Nanni

a sort of

village

and

whole

pa",

But it is more often the case that violence manifests

enchantress.

itself

in the form of natural

to improve material

efforts

In this

by the 'defeated'.

calamities,

acts of God thwarting

all

way

wellbeing and endured in a dignified

fatal struggle with the elements of a hos-

6

life,

Verga's

hardships

the

of

an

unrewarding

and

with

nature

Such is

epic dimension.

peasants and fishermen acquire a universal,

A deep pessithe moral world of I Malavoglia, Verga's masterpiece.

tile

mism inspires

condition.

or desirable

of this apparently inescapable

prevents him from envisaging any possible

His austere, unmitigated presentation fixes the

the novelist's

His conservatism

change.

vision

predicament of his people in a mythical

red by the pounding pace of history.

tragic

As for

tive

in the Italian

verismo

in the sense that

character

theatre,

Verga,

dramatized

their

Rusticana,

La Lupa and Di Giacomo's

compromises

different

cilian

with

own narrative

artistic

world

medium.

being

displayed

panying

adjective

of Verga's

indicated

of the scenes.

the

That

implied

which were not simply

due to the

had to be adequately

of behaviour were to be fully

Cavalleria

low-class

The psychological

"Scene popolari"

and of most veristic

environment

and dramatic

and the choral

identity

between the

was focused through the interaction

fellow

the social

group (neighbours,

workmen).

racters

This technique

certain

own society

customs or patterns

Hence the denomination

appreciated.

the title

have a deriva-

In the case of Verga's first

play, the Sifor the first

time to unfamiliar

audiences

the relationship

and dramatically

relevant;

certain

correctly

stir-

Capuana, Di Giacomo usually

Malavita.

works,

had to be made intelligible

between the individuals

and their

cused if

most plays

hardly

Such is the case of Cavalleria

works.

the original

stillness

foand

accomThe

plays.

structure

of the main chaindividual

and

and pithiextreme liveliness

ness in the dialogues; secondly, a reduction of the plot to one basic

situation

containing in itself

a fasta logical denouement; thirdly,

moving action leaving no space for melodramatic claptrap but relying

entailed:

on unambiguous, striking

strophe (e. g. Santuzza's

firstly,

to mark the progress towards the cata'Mala Pasqua a te! ', in

curse to Turridu:

signals

Cavalleria).

The combination of these elements never reached a fully satisfactory balance in any veristic

play, with the exception of Cavalleria

Rusticana (though some reservations

should be made about Santuzza's

In minor

long speech in Scene 1 and a certain slackening in Scene 6).

indilike

Giacomo,

Di

the

the

tended

to

environment

outweigh

authors,

The overabundance of spectacular and folkloric

details turndramatic build-up into a series of

ed verismo into picturesqueness,

three-dimensional

vignetcharacters into colourful

sensational jolts,

viduals.

7

tes.

nents

It

is

because of the emphasis on the environmental

that the veristic

number of "Scene popolari"

also

in a large

more than the narrative

of Italian

further

e. g.,

dialects

to the marked localization

contributed

como's Neapolitan

the characteristic

evidences

The use of regional

verismo.

Capuana's

works,

three

volumes of Teatro

instead

compotheatre,

regionalism

of Italian

plays:

of most veristic

dialettale

siciliano,

Di Gia-

plays.

Although the Italian

did not match up to the artistic achievements of the narrative works, it had a strong, positive

effect on the stale national repertory of romantic and bourgeois subjects.

The language also benefited from the new veristic

models of a

veristic

theatre

full-blooded,

straight medium. Lastly, a new acting style elow-class

volved in the theatre in order to render the unsophisticated

Away from the grand, heroic, highcharacters of the "Scene popolari".

interpreters

flown postures, veristic

tried to be simple, down-to-earth,

supple,

The greatest of them all was Eleonora Duse (1858-1924), the

natural.

first

Santuzza. Restraint and naturalness distinguished

her approach

to the interpretation

Reporting on

peasant character.

of the Sicilian

the successful Turin premiere of Verga's play (Corriere della Sera, 1516 January 1884), Eugenio Torelli-Viollier

wrote about Duse's acting:

Nella parte della fanciulla

sedotta e che denuncia

1'amante, restando sempre sobria, frenata, semplice,

senza mai un grido, senza mai un gesto violento,

produsse effetti

di alta commozione e fece fremere e piangere gli spettatori.

Duse's new acting technique largely accounts for the veristic

interpretative

approach of great sopranos such as GemmaBellincioni

(1864-1950) and the French EmmaCalve (1858-1942).

In her book of

memoirs, Sous tous les ciels j'ai

chante (Paris, 1940), Calve recalled

the deep emotion she felt the first

time she saw E. Duse act in La

dame aux camelias in Florence: 'Quelle revelation!

Voilä fart

auquel

il faut aspirer....

Elle semble appartenir ä une humanite plus vibrante

(p.

la

Quels

emotion

41).

'

Quelle

nötre.

accents!

que

communicative!

Calve also saw Duse act in Verga's Cavalleria

in Bologna.

Spontaneity, truthfulness,

emotional restraint,

were qualities

Verga tried

hard to retain

in his plays.

Cavalleria

to his great prose works of the early

in the highest degree.

qualities

closest

8

Rusticana was the

1880s and retained

those

In the 1890s,

be experimented

lari".

And it

so happened that

were incompatible

the reduction

of the plot,

background,

the social

the risk

The operatic

apprehensible

compression

roles

providing

in-

Chorus,

to an operatic

and sensationalism.

Cavalleria,

for

effaced

a start,

of the play and emphasized

feelings

of love, jealousy

and re'exotic'

of the low-class

environ-

peculiarities

veristic

universal

on the novelty

capitalizing

venge,

of the minor

picturesqueness

of Verga's

transposition

of the vocal

nature

indispensable

the

aggregation

into

of the aesthe-

and impersonality

subjective

or elimination

of lapsing

from the prose theatre

restraint

Moreover,

or their

the non-melodramatic,

the easily

formal

only

of the "Scene popo-

impoverishment

the essentially

with

in the music drama.

expression

creased

Verga's

of verismo.

premises

level

the transition

in a further

one resulted

could

of verismo

inferior

at the artistically

to the musical

tic

transposition

the operatic

ment.

The casual

quence in Mascagni's

before

pressing

Menasci,

gives

for

literary

subsequent

search

of Cavalleria

the premiere

already

with

encounter

his

a new libretto.

us an idea of his

would do, provided

it

for

His letter

practical,

feasible

texts.

Four weeks

in Rome, the composer was

G. Targioni

Tozzetti

and G.

Rusticana

friends,

Livornese

would be of no conse-

verismo

to them, dated

uncommitted

had a good dramatic

19 April

approach.

1890,

Anything

potential:

Ii genere? A piacere.

Qualunque genere per me e buono,

purche ci sia veritä,

che ci sia

passiýne e soprattutto

il dramma, il dramma forte.

Mascagni's production in the years following Cavalleria Rusticain the choice of libretti.

His operas inna proves his eclecticism

clude the light idyll L'Amico Fritz (1891) and the romantic tragedy

(1895), the long-cherished project of his youthful

Guglielmo Ratcliff

years;

the ludicrous

'dramma marinaresco'

copy of Cavalleria arranged by the faithful

the exotic Iris (1898), the first

of Luigi

Mascagni. In 1901 there follows a revival

Silvano

(1895),

Targioni

Illica's

a carbon

Tozzetti,

and

three libretti

for

of the commedia dell'arte

The opera was preby Illica).

theatres (Genoa, Milan, Turin,

with Le Maschere (libretto

sented simultaneously in six Italian

Venice, Verona, Rome) thanks to an unprecedented publicity

Illica

libretto

by

The

Sonzogno.

third

Edoardo

by

mounted

tradition

9

operation

is the 'leg-

(1911),

Godiva

Lady

Isabeau

the

drammatica'

of

an

adaptation

genda

legend.

In 1910, during the composition of the opera, Mascagni was

interviewed by Arnaldo Fraccaroli

for the Corriere della Sera ("Sotto18 October 1910).

Being asked whether he had fallen back on

Mascagni made one of his memorable statements on the aes-

voce",

romanticism,

thetics of music:

Completamente; e pure ho cominciato col verismo! Ma

il verismo ammazzala musica. E' nella poesia, nel

romanticismo, che la ispirazione

pub trovare le ali.

Verismo

kills

If

music!

is the case,

that

much verismo

managed to seep into

the operatic

not a lethal

dose.

however,

With

Isabeau,

decadentism

ter

and living

to the composer twenty

Il

(2-3

(see below,

lirica

in quattro

written

In one thousand

the poet dramatized

the tragic

Mascagni

later

most of his

production.

Guido Maria

Gatti

those

long-winded

story

D'Annunzio,

an abusive

cut

"Il

finally

in

article

capobanda"

(La Scala,

by D'Annunzio

as a libretto

hundred ornate

and musical

love

of Ugo d'Este's

III,

and their

for

acts,

it

decent

music.

serious

4

for

lines

execution

endeavour

at

Ferrara.

faded

in an essay on D'Annunzio's

Mascagni's

15

his

in fifteenth-century

the opera to three

Yet,

into

Parisina

atti'

Malatesta,

Niccolb

acknowledged

verses

four

Parisina

young stepmother

the command of Ugo's father,

Although

after

the very mas-

Ch. 2, p. 66).

December 1913) was expressly

beautiful

but

apprenticeship

with

September 1892) had dubbed Mascagni

The 'tragedia

the composer.

a useful

collaboration

years

presumably

was not romanticism

symbol of the movement, Gabriele

reconciled

Mattino

Cavalleria;

it

It'was

Mascagni subscribed

to.

Jotthe

him

which prepared

gratifying

wonder how

one might

out

like

libretti,

to turn

Such a wide range of subjects and styles shows how every literary movement or fashion which evolved in Italy in the last quarter of

the nineteenth century left its mark on the libretti

set by Mascagni.

The same could be said, to a certain extent, for the production of

other composers of the Young School. The Orientalism of Iris antici(1904); Il piccolo Marat, written by Mascagni

pates MadamaButterfly

as late as 1921, is in line with Giordano's

both are French Revolution subjects treated

Unfortunately

Andrea Chenier (1896):

in a 'veristic'

style.

for Mascagni, only a few excerpts from these ope-

10

included

in

have

recordings and

still

are

and

escaped oblivion

ras

from

"Intermezzo"

Duet"

"Cherry

the

and

concert programmes: e. g.,

"Dream", the "Hymn to. the Sun"

Guglielmo Ratcliff's

L'Amico Fritz,

Mascagni's operas, forming ideal

An attempt at 'editing'

made by Giannotto Bastianelli

suites with its best parts, was first

in his Pietro Mascagni (Napoli, 1910), perhaps the-earliest

compre-

from Iris.

hensive study on the 'plebeian musician',

called him. In

as the critic

more recent times, John W. Klein devoted an essay to "Pietro Mascagni:

(Musical

Enigmatic

Figure"

Opinion, February 1937) in which he dean

known operas and stated that: 'There can be little

doubt that Mascagni's finest music is not to be found in the early oneact opera that made him world famous and that he himself regards as

fended those lesser

sentimental

and distinctly

The major

sustained

ture

inspiration

With all

its

throughout

musical

pace which effectively

strophe

and secures

to some of his later

in Mascagni's

in fatal

which results

ness.

fast

flaw

inferior

stylistic

forgotten

a three-

lapses

or four-act

of tension

'primitivism',

leads

operas

is

operas'.

an inadequately

dramatic

and in stylistic

Cavalleria

to the veristic

patchi-

Rusticana

shout

struchas a

of the cata-

consistency.

When the whole of Mascagni's production is considered - fifteen

operas from Cavalleria to Nerone (1935) - it becomes clear how misrepresented he is under the label of 'verismo' composer. That early

and unrenewed choice cannot be assumed as a permanent aesthetic position as regards both the libretti

and the musico-dramatic features of

the composer's works.

Literary

verismo recorded its highest achievements in the early

1880s, that is in the years which witnessed the renewal of Verdi's

Verga's first

after the long pause following Aida (1871).

activity

of veristic

collection

short stories Vita dei Campi appeared in Milan

in the summer of 1880; his best novel, I Malavoglia, in 1881. In 1883

Verga turned one of those short stories into the successful play Cavalleria Rusticana (Turin, 14 January 1884). Towards the end of the decade, Verga published the second novel of the cycle of the 'Defeated',

Mastro-don Gesualdo (1889) which coincided with the appearance of D'AnAs for Verdi, in 1880 he planned the revision of

nunzio's I1 piacere.

Simon Boccanegra which was to bring together

for

the first

time the age-

ing composer and the former 'scapigliato'

In the followArrigo Boito.

ing years, they worked on Otello (La Scala, 5 February 1887).

11

There is a well-known letter by Verdi to Giulio Ricordi, dated

20 November 1880, with an interesting

reference to the new veristic

Verdi is discussing the possible improvements to the second

trend.

the

the

old verBoccanegra

of

cabalettas

mentioning

after

and,

act of

in

harmony

fashions

the

he

and

new

on

comments

makes

sarcastic

sion,

digression

launches

into

then

on verismo:

a

and

orchestration

Ahi, ahi!

Ah, il progresso, la scienza, il verismo...!

Verista finche volete, ma... Shakespeare era un verista,

noi sima non lo sapeva. Era un verista d'ispirazione;

Allora tanto fa:

amo veristi

per progetto, per calcolo.

I1 belsistema per sistema, meglio ancora le cabalette.

lo si e che, a furia di progresso, 1'arte torna indietro.

di naturalezza e di semL'arte che manca di sponaneitä,

plicitä,

non e piü arte.

In Charles

Osborne's

which isnot

literary

in the cultural

took

innovation

in his

he made that

quite

Once more,

pressions

stance

save that

his

own way.

clear

ideas

for

something

seemed to challenge

the next moment he would be pursuing

For Verdi,

'copying

on 'truth'

of admiration

whenever

in an earlier

between

distinction

subtle

who was by then a well-known

6

In his characteristic

way,

of Milan.

circles

or orthodoxy

'realism'

in particular,

a conservative

tradition

with

must have had in mind the new

the same because Verdi

and Verga,

trend

figure

Verdi

quite

is rendered

'verismo'

translation,

'vero'

meant artistic

letter

to Clara

and 'inventing

the truth'

in conjunction

7

'Father'.

were put forward

Shakespeare,

the

Maffei

truth,

and

about the

the truth'.

with

ex-

The evolution

Italian

opera is marked,

of late nineteenth-century

among other events, by Verdi's realistic

approach to Shakespeare tin(the

Boito

by

ged with 'Scapigliatura'

morbid and

elements contributed

in Otello,

The musico-dramatic and

the grotesque in Falstaff).

references

vocal novelties of Otello were to become one of the stylistic

of the Young School.

the evil

The heyday of 'operatic verismo' - 1890-92, i. e. the period of

Mala Vita and Pagliacci - comes half way between the 'dramCavalleria,

(1893).

(1887)

In

lirica'

Falstaff

'commedia

Otello

the

lirico'

and

ma

the search for musical precedents, the widespread belief that the realiits

libretto

than

depends

the

on

rather

on

stic character of an opera

'Shakespearean'

the

has

led

to

treatment,

overlook

many

writers

musical

Verdi in favour of the earlier

Traviata

12

(1853),

often

seen as a pre-

the

its

the

risand

subject

contemporary

of

on

grounds

work

for

Leibowitz,

Rene

femme

the

theme

example, stated:

entretenue.

of

que

'veristic'

le

La

I1 est clair

traviata

sinon

preconstitue,

que

la

1'etape

du

plus radicale

opera

veriste,

moins

mier

Et si, de la sorte,

sur la voie qui devait y mener.

le verisme a contracte

envers

une dette inneffagable

etrange et paradoxal

la musique de Verdi,

n'est-il-pas

ä un certain

de voir,

moment, cette musique condamnee

dire au nom de cette esthetique

si j'ose

meme?'8

In the rich

tic

it

verismo',

is significant

du neant'

'l'usine

on its

vallo

Both works,

do without

being

The realism

tify

a 'veristic'

stressed

having

borrowed

Murger's

argued the fastidious

tarted

'operaas

of an adverse

re-

in 1903.

Puccini

Next

and Leonca-

Scenes de la vie

Debussy,

'could

de

certainly

up in music. '9

of the French

reading

of Dumas's play

treatment

structures

in the context

at the Opera-Comique

revival

of it

definition

who had dared to use La Dame aux camelias,

were blamed for

Boheme.

comments on Italian

Debussy's

that

be coined

should

view of La Traviata

to Verdi

of French derogatory

repertoire

source

is certainly

of La Traviata.

Verdi's

is consistently

respectful

not enough to jusmusico-dramatic

of the formal

have

Some modern scholars

'melodramma'.

of the romantic

10

in his essay

One of them, Giovanni Ugolini,

this point.

"La traviata

ei

rapporti

di Verdi

con 1'opera

between the harmonic

pointed out similarities

11

Otello

and the style of the Young School.

verista",

and vocal

has also

writing

of

In a later

"Umberto Giordano e it problema dell'ocontribution,

Ugolini discusses in detail the whole problem of definpera verista",

ing a 'veristic'

opera and concludes that it is a question of musical

12

dramaturgy and vocal writing.

He also singles out the main characteristics

of a 'veristic'

style which could be taken as representative

School

in

Young

in

the

Italian

and

operas

composed

verifiable

most

of

The chanineteenth century, whatever their subject matter.

can be summedup as follows:

racteristics

with sentimental languor;

a) passionate tension alternating

b) violent contrasts or extreme delicacy in the vocal line,

the late

c)

the orchestra following

and supporting;

equal treatment of the various components of the operatic

);

(recitative,

solo pieces, ensembles, etc.

structure

13

of dramatic and vocal differentiation

elimination

parts in ensemble pieces;

no bel canto coloratura.

d)

e)

These stylistic

features

tion

of new structures

to dramatic continuity.

pieces, b) a flexibility

in late

should be considered within the evoluItalian

opera tending

nineteenth-century

That means: a) a gradual obliteration

of set

of the duet form to accommodate musical discopresence of the orchestra providing textural

c) a pervasive

In this respect,

course,

hesion.

of

Otello

and Falstaff

are much more innovative

than the modest products of the Young School, with the exceptions of

Puccini's Manon Lescaut (1893) and La Boheme (1896).

In the limited

Rusticana,

of operas based on veristic

subjects (Cavalleria

Mala Vita, and their imitations)

features

the stylistic

(one or two

mentioned above are emphasized by the small proportions

acts) and the sensational events of the libretti.

production

Pagliacci,

In those

esteem:

Alfredo

untimely

death

Italian

School

itinerary

tic

stage.

fruitful

Catalani's

(1893)

another opera won success and critical

La Wally (La Scala, 20 January 1892).

The

years,

of the unfortunate

of a gifted

musician

heeding

the noisy

without

13

Lucchese deprived

who proceeded

irruption

on his

of verismo

the Young

own artistic

on the opera-

In 1891, the music critic

journal Nuova Antoloof the literary

Gazzetta Musicale for listyia, Girolamo A. Biaggi, quoted Ricordi's

ing fifty-two

new Italian

operas premiered in 1890, each classified,

according to the outcome, in one of four

'mediocre',

'cattivo'.

Only two operas

Loreley and Mascagni's

namely Catalani's

'Ma (vedi giuochi

commented with regret:

grades:

'buonissimo',

'buono',

were entered under 'buonissimo',

Cavalleria Rusticana.

Biaggi

della

) a galoppo didi mezza Europa,

fortuna!

steso la Cavalleria Rusticana ha giä Corsi i teatri

e la povera Loreley, dagli applausi e dalle acclamazioni

Regio di Torino, passb alla quiete dell'Archivio

Ricordi

del teatro

e non si mosliterary

Mascagni could, at least, work on a valuable

would not have. In the following years,

source which his imitators

the rise of 'operatic

verismo' was marked by a progressive degenera-

se piü! '14

starting with the

excess, sensationalism,

picturesqueness,

Paone and only opera which has survived to our days, Leoncavallo's

A derogatory implication

was attached to the expression and,

gliacci.

in the process of time, it affected any consideration

of the literary

tion

into

14

movement in relation

stic' decade.

'veri-

to the operas of the 1890s, the so-called

School, GiacoTurning to the major figure of the Young Italian

literary

his

be

that

veit

Puccini,

with

contacts

emphasized

must

mo

Mascaby

inaugurated

decade

In

the

totally

unproductive.

rismo were

two attempts were made to involve Puccini in the comVerby

Giulio

Ricordi

a

wanted

who

operas: one

position of veristic

the

Sonzogno,

his

House

for

his

to

owner

rival

antagonize

opera

ghian

Bracco

Roberto

by

Neapolitan

the

Cavalleria;

the

playwright

other

of

gni', s Cavalleria,

who was willing

(1895).

The first

to adapt his veristic

one-act play Don Pietro Caruso

led to a libretto

derived from

project actually

Verga's short story "La Lupa" but Puccini found it uncongenial and

dropped it in favour of La Boheme. Bracco's play was a psychological

with

set in a drab interior,

study of contemporary Neapolitan life,

folklore

to

three

or picturesqueand

no

concessions

characters

only

in

for

treatment

the

It

an

operatic

unsuitable

certainly

was

ness.

fashionable 'veristic'

style of the 1890s unless Puccini were to exPietro

Don

technique.

Straussian

conversation-piece

periment with a

idea

the

of a possible

so

not

consideration,

was refused after careful

Ricordi's

In a letter to Carlo Clausetti,

with Bracco.

collaboration

Bracco

the

between

in

Naples

composand

and

middleman

representative

er, Puccini outlined his own requirements in terms which remind us of

Mascagni's instructions

wanted libretti

Tozzetti

to Targioni

containing

sensation

quoted above.

and drama:

Puccini

(Torre del Lago, 10 November 1899)

drammatiche,

forti

sensaziosensazioni

e

grandi,

...

nali, dove it sentimento si eleva e cozzandosi, urtandosi, produce attriti

drammatici, quasi epici; insommanon desidero essere terra terra (non a questa

Mi euna allusione ne censura ai lavori di Bracco).

sprimo male, ma tu mi avrai capito: "il faut frapper

he public"!

Ci vuole qualcosa di insolito,

sempre,

in teatro.

Il pubblico ha sete di nuovo, c. vogliono

trovate musicali,

essenzialmente musicali.

The subject matter of an opera did not have to be 'terra

is to say simple, down-to-earth;

we might say veristic.

terra',

that

Puccini

wan-

and great passions; above all, something musical'il teatro melodrambecause, he continued in the letter,

ly effective

The

di

it

altra

teatro

a

whole paragraph

ben

prosa'.

the

cosa

matico

Tosca,

illustrate

the

of

be

to

letter

characteristics

used

might

of the

ted dramatic tension

15

the opera which had just been finished by Puccini and was about to be

1900).

in

To14

January

Nothing

(Teatro

Costanzi,

in

Rome

premiered

it is sensational and full of dramatic

sca is 'terra terra';

it has all the suitable ingredients to 'frapper le

tations;

The case of Tosca exemplifies a false idea of verismo

negatively on the literary

movement of that name.

reflected

confronpublic'.

which has

As late

dediGarner

1985,

in

Cambridge

Opera

Tosca,

Mosco

Handbook

the

on

as

After defining

cated a chapter to "Naturalism in opera: verismo".

opera as a 'milestone

of verismo', he stated:

Puccini's

in the relatively

short-lived

history

At the heart of verismo is excess

- excess of passion

and emotion leading to brutal

murder and/or suicide;

climax follows

climax in quick succession,

and no soonthan it is destroyed by a coner is a mood a '6tablished

trasting

mood.

context, Garner meant by 'verismo' the musico-dramatic

School, a denomination he accepted in

techniques of the Young Italian

As such, 'verismo' might

the sense specified in the present study.

be as good as any other label to identify

a known product, and Garner

In that

would be in agreement with other scholars who adopted that term to

identify

But

an autonomous aesthetic trend in the musical theatre.

Carner also connected that meaning with the literary

movement which

he saw as partly springing from 'a certain tendency to realistic

treatin the national character. ' He mentioned

ment, reflecting

a trait

Verga, Capuana and, in retrospect,

Boccaccio's Decameron and Dante's

Inferno (Manzoni's realistic

novel I promessi sposi was unaccountably

At such a high level of generalization,

a similar comparison could be tried for many other 'isms' (romanticism, symbolism,

)

in the case of a complex text

using the same works, especially

etc.

like Dante's Inferno.

missed out).

Leaving aside a discussion of realism as a general trend in

it must be pointed out that a misunderstanding of verismo

literature,

far-fetched

in

to

Verga's

such

a

seems

particular,

underlie

art,

and

been

has

Formal

excess,

and

not

emotional

restraint,

evaluation.

Tosca

dominant

feature

Verga's

the

works.

veristic

of

singled out as

shocker' of Joseph Kerman's catchy

might even be the 'shabby little

definition,

but,

with verismo.

if

that

Puccini,

is the case, the reasons have nothing to do

Illica

and Giacosa contrived a melodramatic

16

free

to

'veristic'

play

sentiand

allowing

pace

a

at

mechanism working

frenzy,

Scarpia's

ingredients:

decadent

sexual

sadism

and

mental and

Giuseppe Giacosa, himself a

Tosca's sensual and possessive nature.

text

the

the

of

artistic

quality

of

modest

aware

was well

playwright,

French play and

He disliked the original

he was handling for Puccini.

Sardou. In a letter to Ricordi writits shrewd manufacturer Victorien

ten in 1896, he pointed out as the major fault of the play the contriexpansion: 'I1

with no space for lyrical

guaio piü grande sta in cit, the la parte dirt cos! meccanica, cioe it

17

vi ha troppa prevalenza a scapito della poesia'.

congegno dei fatti,

Nevertheless the final result of the laborious process of creation was

facts

vance of sensational

which has so far

an effective,

musically poignant operatic thriller

defied slashing criticism

and snobbishness.

The musico-dramatic

techniques

by the Young Italian

the ones practised

certainly

'veristic'

may be applied

and the vocal

to themin

that

sense.

of Tosca are

style

School,

and the, term

On the other

hand,

the lack

background,

keep Tosca miles

of social

away from literary

verismo and, to a large extent,

also from the early

Pagliacci,

veristic

operas of the 1890s.

with all the sensation

of

the decadent

the double

elements,

murder on stage,

of the interaction

stead,

is

still

an opera with

even in their

absence.

literation,

of the historical

Sardou's play is particularly

Cavaradossi.

indulging

the fundamental

between environment

stage

ter

respects

in vocal

He is just

exploits

'big'

The compression,

and political

noticeable

a 'signor

like

the

roles

dominating

which

in the character

'Vittoria!

the

and sometimes the ob-

references

tenore',

in-

Tosca,

and main characters.

individual

principle

veristic

of the pain-

in Puccini's

Vittoria!

lengthen

own words,

' of Act

II

or his prophetic statement in Act I: 'La vita mi costasse, vi salvert! ',

hitting

A generous aesthete rather

on the B natural above the stave.

Cavaradossi dies gracefully,

'con scethan a committed 'volterriano',

Rome is 'heard' in the

nica scienza', contemplating his dream of love.

introduction

'veristic'

of Act III with the Shepherd's song and the Matin bells, but even the Eternal City is under the spell of the perverse

Baron Scarpia as Tosca tells us after stabbing him to death ('E avanti

The whole opera hinges on these two perAll

the

female

figures:

the

the

antagonist.

male

protagonist,

vasive

BonaAngelotti,

the

of

the

the

news

prisoner

political

escape of

rest,

in

is

instrumental

Marengo,

battle

the

setting

of

parte's victory at

a lui

tremava tutta

Roma!').

17

the melodramatic clockwork in motion.

The preconception about sensationalism and excess as distinctive

investigatheir

led

to

has

traits

concentrate

many writers

of verismo

of musical realism on operas such as Tosca, often reaching oppohave

tried

denigrators

In

the

this

case,

particular

site conclusions.

hard to coin sensational abuse (Kerman); the supporters have overstated

tion

In his

character of the opera's undisputed 'verismo'.

Cambridge Opera Handbook, Carner defined Tosca as 'the opera prophetic

(p. 9).

of the modern music-theatre'

the innovatory

Musical

realism

suitable

representative:

not with

a bang like

as 'low-life'

in these

La Boheme (1896).

Tosca,

discussing

seen in Puccini's

ers of doubtful

Mimi dies

La Boheme, which

virtue

brings

on to the stage'

with

a whimper,

the recurrence

Carner mentions

in veristic

operas,

'Pre-veristic

opera already shows this

characters

terms:

but

opera as a quieter

as 'pre-

the opera qualifies

and apparently

In the Tosca Handbook,

veristic'.

Puccini

has an earlier

of artists

La Boheme

best

tendency,

poor artists

with

(p. 9).

Classifying

lov-

their

as 'pre-

veristic'

an opera completed in 1895 seems to dispose of the notion of

1890 as the Anno Domini for 'operatic

unless it is targeted

verismo',

on Puccini's

own progress towards the 'verismo'

of Tosca, which is just

La Boheme does not lead to Tosca but to the 'roman

Louise (1900) by Gustave Charpentier,

bein which the milieu

musical'

than the individual

comes more important

characters

and the big city

as questionable.

(Paris)

noises.

is

18

a real

musical

presence

with

all

its

variegated

voices

and

The affinity

with opera comique for its blend of pathos and humour and the sugar-laden sentimentalism make La Boheme a late-romantic

opera with some of the youthful irreverence and exuberance of the Milanese 'Scapigliatura'

which Puccini,

Illica

and Giacosa had personalThe connection between the

ly experienced in their earlier years.

French 'bohemiens' and the Milanese 'scapigliati'

by Felice Cameroni in his preface to the Italian

had been stressed

translation

of Mur-

ger's Scenes de la vie de Bohemepublished by Sonzogno with the title

La Boheme: scene della scapigliatura

parigina (Milano, 1872). La Bolibretin

the

heme is not, strictly

speaking, a veristic

opera either

to or in its

certain

social

musical treatment.

(chilly

winter

ambience

background (poor artists

Yet, the careful

in a big city),

and room-mates),

18

illustration

the delineation

the low profile

of a

of a

of

and the avoidance

the characters

tic

display

able

rative

they

of the romantic

'operatic

broke the continuity

in traditional

(relationship

daily

routine,

of the dramatic

The reduction

operas.

Mimi/Rodolfo

the poetry

the conversation

style,

true

and his

each of the four

within

role'

no less

and violent

Puccini

verismo'.

dimension

'melodramma'

feelings

of passionate

'big

likely,

the bohemian life

to-

point

of the fashion-

gestures

introduced

build-up

of the plot

a nar-

and, in so doing,

tableaux,

which was still

to one basic

used

situation

+ poor health

of small

of Mimi), the lyricism

of the

(e. g., Mimi's pink bonnet),

things

the opera a realistic

to life,

the bohemian life

and girls

all

than from the empha-

librettists

give

artists

logic,

La Boheme moves away from the heroism

conception.

wards a new operatic

and idealism

of the

in Milan

make those

character,

in Paris,

or,

more

or Turin.

In conclusion,

the advent of realism in the musical theatre is

best understood as the development of new musico-dramatic structures

and a new vocal style which marked a radical departure from the styliItalian

zation of nineteenth-century

derived from contemporary literature,

The choice of subjects

possibly dealing with low-life

opera.

does not in itself

stories,

make one opera more realistic

Nor can an opera be identified

because it

as 'veristic'

Too often assumed as typifying

cess and sensationalism.

than another.

exhibits

ex-

verismo,

such

do, in fact, belong to a minor genre which originated

characteristics

from Mascagni's prototype and can conventionally

be defined as 'operatic verismo'.

This genre had little

bearing on the evolution of late

nineteenth-century

Italian

opera and slowly petered out in the early

Leoncavallo's

years of our century.

Pagliacci is the only survivor

of the numerous offspring

of Cavalleria.

The influence of literary

verismo - exercised through'theatriin the pithiness of

cal more than narrative works - manifested itself

dialogue, the more realistic

language often enriched by vernacular

interpolations,

simple and fast-moving stage actions,

background in dramatic characterization,

a new relevance

emphasis on the

of the social

importance of acting skills

along with good singing in performance.

The term 'verismo' may well be used with reference to the new

School - for operas based on realistic

style of the Young Italian

subjects

or simply exhibiting

vided no undue connection

that name.

realistic

is implied

19

musico-dramatic

with the literary

features

- pro-

movement of

2.

and its

subjects

unequalled

a strong

with

and folkloric

customs

South,

Sicily

life

of Italy's

peculiarities

and Sardinia

inherent

ness and sensationalism,

irreversible

trend

those

with

popularity

19

in Germany.

particularly

in the veristic

plebeian

a tremendous

enjoyed

of meretricious

gatherings

in village

became an

theatre,

but also

jealousy

rural

picturesque-

in Italy

were quickly

squares,

into

This

source with

ingredients:

the

by mediocre comregions

melodramas.

not only

In the absence of a literary

the libretti

of Verga's Cavalleria,

ful

poorer

- were eagerly exploited

The tendency to lapse

and shrewd versifiers.

posers

sorts

Many operas were

and are today more a subject for

The

than for musical analysis.

studies

and statistical

veristic

characterization.

regional

composed which had an ephemeral

sociological

for

a fashion

started

success

Cavalleria

caused by Mascagni's

1890s the sensation

In the early

Rusticana

Rusticana

of Mascagni's Cavalleria

The offspring

the artistic

minor

genre

abroad,

qualities

assembled with

and contrasted

surroundings

love,

all

joy-

or urban derelict

Violent

death was an obareas, superstitions,

curses and swear-words.

ligatory

device to round off a story with an effective

coup de theatre.

Knives were by far the most popular weapon, but there was also the ocSilvano).

Some librettists

casional

to sophgun (Mascagni's

resorted

isticated

forms of suicide

such as asphyxia from coal fumes (Samara's

La martire)

or from the smoke of a hay-barn

set

on fire

(Floridia's

Maruzza).

From a sociological

point

of view, these operas were nothing more

than consumer products for middle-class

audiences whose conservatism

was clearly mirrored in the portrayal of peasants and workers indulging in individualistic

vendettas but quite harmless in social and political

terms.

A tribal

sensitivity

and no class-consciousness

made up

the most exciting operatic peasant. Regional costumes, idioms and

1890s

In

the

the

the

enhanced

picture.

witreal

world,

words

slang

in

heavy-handed

mainly

social

and

repression,

unrest

nessed growing

SoIn 1892 the Italian

the 'Mezzogiorno' but also in Northern Italy.

1894

'Sici1892

the

founded

in

Genoa.

Between

Party

and

was

cialist

lian

Fasci'

developed into

an organized working-class

movement which

heavy

hundreds

sentences.

and

of

arrests

with

repressed

ruthlessly

was

In Milan, in May 1898, popular protest for the high price of bread was

20

by troops

crushed

hint

ches de vie'

operas

of those years

romantic

geance.

The different

together

with

a veneer

of modernity.

themes of passionate

guise

love,

in fact,

betrayal

variand ven-

of the new 'heroes',

ingredients,

have invented

musicologists

The 'tran-

classes.

were,

and

is never the

there

language

and the hybrid

and folkloric

environmental

Some Italian

in the lower

in the libretti,

as pretexts

adopted

on the old

ations

hundreds

discontent

at social

of demonstrators

and killing

In the veristic

passers-by.

slightest

shooting

gave these

humorous definitions

operas

for

look-alikes:

the 'aesthetics

such a noisy pack of Cavalleria

of the

(Rubens Tedeschi);

knife'

'the melodrama of depressed areas' (Rodolfo

20

Celletti).

One could chart the problem areas of post-Risorgimento

Italy

by simply grouping these operas according

to their

setregional

tings.

The list,

far from being exhaustive,

to the decade

and limited

1890-1900,

would read as follows:

SICILY:

Frontini,

(1894);

Bimboni,

Un mafioso

NAPLES:

Floridia,

Santuzza

(1895);

Maruzza

Mineo,

(1896).

CALABRIA: Leoncavallo,

PUGLIA:

(1893);

Malia

Pagliacci

(1892).

Mascagni, Silvano. (1895).

Giordano, Mala Vita (1892);

Tasca, A Santa Lucia

(1892); Spinelli,

A Basso Porto (1894); Sebastiani,

A San Francisco (1896).

ABRUZZO: De Nardis,

TUSCANY: Luporini,

Stella

(1899).

La collana

di Pasqua (1896),

dealing

with coal-miners.

SARDINIA: Cellini,

Vendetta sarda (1895).

A few more operas might be added dealing

with particular

themes rather

than exhibiting

a specific regional characterization:

(1892), set in the bush around FrosinoCilea's

Tilda

Francesco

(halfway between Rome and Naples) and dealing

ne in Ciociaria

with brigands and French troops at the end of the eighteenth

century but with a clear reference to a contemporary problem.

In the aftermath of the Risorgimento, the new Italian

state

had to cope with widespread brigandage in the South. The

problem was tackled with heavy-handed repression by the army.

21

Carmen:

in

has

with

common

something

of the opera

The plot

hide-out

to the one of the smugglers'

is

a sensuous

na di

strada')

in the mountains;

Tilda

gipsy.

(1896;

Stellina

trice'

(an ironer),

environment.

of the score.

room where Stellina,

receives

operaio',

and surrenders

Gastaldon

was also

to his

which marked a false

(see Ch. 2).

free

a in

The setting

renewed passionate

Rusticana,

start

'L'azione

Luigi,

the composer of the very

Cavalleria

with

is

'stira-

a twenty-year-old

her boyfriend

1905

until

not performed

in one act dealing

lirica'

in an urban working-class

Italia'

is the vague indication

little

of

Bizet's

love

a tidy

e canteri-

and has a couple

who dances two Saltarelli

Gastaldon's

Stanislao

in Florence),

a 'novella

on Verga's

similar

('saltatrice

streetsinger

and wilful

songs like

popular

in the wood is

headquarters

the scene of the brigands'

'giovane

a

advances.

first

opera based

namely Mala Pasqua! (1890),

in the history

of operatic

verismo

(1895),

Smareglia's

Antonio

in

Istriane

Nozze

the

set

village

of Dignano in Istria,

a problem area because of its position

at ethnic

1Y

and political

crossroads

between Yugoslavia

and Ita-

As for

the music of these operas, popular songs accompanied by

guitars and mandolines, tarantelle

and saltarelli

or other local dances,

drinking songs, litanies

hymns, were inserted on the slighand religious

The vocal style and the musico-dramatic structures had

test pretext.

three major references: the scrap-yard of the dismantled romantic melodrama, the contemporary 'verisit^'

School and

style of the Young Italian

The third stylistic

the drawing-room song style.

reference, the 'romanItaly and

was a popular genre in late nineteenth-century

za da salotto',

had its

such as Francesco Paolo Tosti (1846-1916), but

by operatic composers. Sentimentalism and langit was also cultivated

uor, a mild sensualism and a melancholy pose borrowed from contemporary

decadentism, characterized the texts which were set to plaintive

melodies

own specialists

The

the pleasure of dreamy young ladies and their patient suitors.

has a good

second most famous veristic

opera, Leoncavallo's Pagliacci,

hybrids.

The composer-librettist

gave the unexample of such stylistic

for

Silvio,

in the love duet with Nedda (I, 3), a piece in

couth villager

the style of a 'romanza' both for the words and the music. Over 'mur-

muring'

semiquavers,

voluttuosamente',

him only to leave him with

mezza voce,

ed'

ardent

Ex. 1-

melody 'sempre a

a graceful

has 'bewitchthat the girl

complaining

the baritone

sings

memories of

(Ex.

1):

spasms of voluptuousness'

Leoncavallo,

I,

Pagliacci,

)

Andante appassionato. (i.:

s+.

to

trying

(lovingly,

and

'warm kisses'

given

'amid

3

semfýss a mezzo voce, voluluosamenle

move her)

ý

8

hast

Why

E al

lor

-

Andante appassionato. (:.. a+)

p"

e lrgrile'ssiýno semýse

.

thoutaught

ýet chä,

me_

di,'..::

"

's 1

ýý

h

---=

ýýý

S

loves

I'm

do Ii

if,

ma_gie stor

w'Aui slre. ga

=i

i

la

to

_

-1

$e

leave

thou wilt

la : sciga

auoi

_

02

-

C79-P Zo

is no exception as regards the mixture of compositionoperas.

registers,

commonto most veristic

al styles and linguistic

Echoes from contemporary literature

can be found in many of them. At

the very end of Pagliacci Leoncavallo thought it appropriate to show

Pagliacci

Sicilian

by

borrowing

Verga's

his

typical

most

cultural

awareness

off

'Santo diavolone! ', to give an unmistakably veristic

mark to

oath,

23

me

Mai

Silvio's

steps

last

to defend

forward

he exclaims:

erary

noticeable

Decadent

After

an affair

man.

The 'dishonoured'

fire

with

to the hay-barn

his

beloved

diavolo!

'Santo

echo is

Floridia).

As the Calabrian

line.

Fa davvero...

ingredients

a peasant

peasant

killing

lures

herself

His words might

into

a veristic

marries

lit-

a rich

story.

wo-

the man to her house and sets

Before the catastrowith him.

how her memory haunts

in D'Annunzio's

remarkable