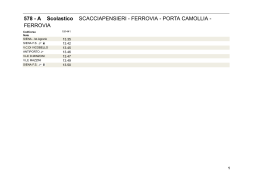

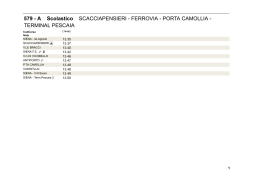

The Biblioteca comunale degli Intronati for The James Madison Council Manuscripts, incunables, drawings and prints Biblioteca comunale degli Intronati Siena The Biblioteca comunale degli Intronati for The James Madison Council Manuscripts, incunables, drawings and prints Siena, Biblioteca comunale degli Intronati 21 June 2011 Volume published on the occasion of the visit of The Madison Council from The Library of Congress, Washington Project management Luciano Borghi Curated by Annalisa Pezzo Selection of the works Rosanna De Benedictis Texts Sara Centi Rossella De Pierro Annalisa Pezzo Chiara Razzolini Bibliography Mirko Francioni Annalisa Pezzo Translations Laura Bailhache Fabiana Bassani Veronica Santini Elisabeth Watts Piccia Neri Translations Editor Piccia Neri Photography Marco Bruttini Marco Muzzi Graphic Design Number Six, The Village Produced by Vanzi S.r.l. Industria grafica, Colle di Val d’Elsa (Si) Acknowledgments Lorenzo Catacchini, Alessio Duranti, Roberta Ferri, Pietro Indelicato, Stefania Jahier, Marco Marcellini, Roberta Mari, Isabella Neri, Marco Pierini The technical descriptions at the beginning of nos. 1-12, 16, 21, 25 are by Rossella De Pierro Abbreviations BMC - Catalogue of Books... 1908-1972 IGI - Indice generale degli incunaboli... 1943-1981 ISTC - The Illustrated Incunabula... 19982 Biblioteca comunale degli Intronati Istituzione del Comune di Siena Chairman of the Board Bernardina Sani Administrative Board Giovanbattista Alfano Carlo Ciatti Gianna De Santi Luigi Maria Di Corato Anna Gambelli Massimo Tedeschi Barbara Valeriani Chief Librarian Luciano Borghi The works described in the present catalogue were selected and displayed on the occasion of the visit of The James Madison Council delegation from The Library of Congress, led by the Librarian in Chief, Dr. James H. Billington, on 21 June 2011. The exhibition and the booklet represent a small tribute and our way of expressing our gratitude for inviting the Biblioteca comunale degli Intronati di Siena to be part of the World Digital Library network, under the patronage of the Library of Congress and Unesco. We are honoured to be among those historical Italian libraries that are worthy of your visit, and grateful that our rich heritage can be put to its best use and bring a significant testimony to the history, culture and art of Europe in your global project. The works in this selection, out of the very masterpieces in our collection, were chosen for their rarity and the exceptional artistic value of the illustrative programmes accompanying the texts, be they historical, liturgical, juridical or literary. In a few cases the pieces are not part of a book but separate works of art, such as drawings and engravings. The twenty-five selected works – mainly by painters, engravers, architects, engineers from Siena, or active in the area – can be regarded as outstanding records of the city’s artistic and cultural heritage and its popularity; they also often reflect the events in the collectors’ market and bear trace of the rich and vibrant network of intellectual connections that finally led them to the Library. The documents described in the booklet and on display on this occasion represent an extremely valuable, but very small, section of an extraordinarily large cultural legacy in constant need of protection, preservation and restoration within a wider context of research, appreciation and fruition. My most sincere thanks go to those who devote their working lives to the achievement of these goals and, of course, to all those who contributed to the organisation of this event. Moreover, on behalf of all the staff of Biblioteca comunale degli Intronati di Siena, of the Board of the Library, of Sien a City Council, I wish to express again and with great satisfaction our heartfelt gratitude to the Library of Congress and to the James Madison Council. Luciano Borghi The Chief Librarian Giovanni Bruni, Portrait of Giuseppe Ciaccheri, 1823, oil on canvas. Siena, Biblioteca comunale degli Intronati A brief history of the Biblioteca comunale degli Intronati The origins of the library date back to 1758, when the archdeacon Sallustio Bandini donated his books (2886 volumes at the time) to the University, in order to provide it with an adequate book collection. Bandini set as conditions for the bequest that the library should be accessible to the public and under the management of the abbot Giuseppe Ciaccheri. The donation provided the starting point for a very important pole of cultural attraction in the building previously occupied by the Sapienza (a part of the University of Siena) and still occupied by the library to this day. The starting collection was remarkable, and kept being enlarged thanks to donations and funding from the government of the Grand Dukes: however, even more important was the fact that librarian Ciaccheri’s long-standing passion for local art and painting channelled various types of art collections into the library. Amongst the first book donations from private citizens, the one from Giovanni Sansedoni (1760) is worth mentioning, as well as the one from Adelagia Benvoglienti (1769), the daughter of the Sienese scholar Uberto, who bequeathed her father’s manuscripts and letters. In 1783 the library shelves welcomed a significant series of manuscripts coming from the dissolution of convents and secular companies ordered by the Gran Duke Pietro Leopoldo. The earthquake that shattered the city of Siena in 1798 brought serious damage to the Library building, forcing a closure of the venue, which only partially re-opened in 1803. The library was closed again five years later, in 1808, following the decision by the French occupiers, within a general restructuring of the educational institutions in Tuscany, to discontinue the activity of the University of Siena and as a consequence of its library. There was an informal re-opening in 1810, under the direction of the Franciscan monk Luigi De Angelis. The French government decree that allowed its re-opening joined the library of the Sapienza with that of the convent of Sant’Agostino, placing the new institution under the jurisdiction of the ‘Civic Community’ of Siena. Officially, the opening ceremony of the new ‘civic’ library only took place in 1812. Mostly, the new librarian De Angelis concentrated his efforts on making an inventory of the existing book assets and acquiring new assets from the convents of the Sienese territory after their dissolution. Under De Angelis’ direction the library confirmed and expanded its secondary function as a museum, for the substantial series of conspicuous examples of Sienese art that the Franciscan managed to obtain for the building of La Sapienza. These works would later provide the first nucleus for the future Istituto di Belle Arti and for the Pinacoteca Nazionale. De Angelis died in 1833. During the period immediately before the unification of Italy, under the management of the librarian Francesco Chigi, the library suffered progressive and constant cuts to its funding. Between 1844 and 1848 the seven volumes of the important Indice per materie della Biblioteca comunale di Siena were published, edited by Lorenzo Ilari and listing both manuscripts and printed materials in the library. In the years following the unification (1861) the library remained the recipient of book donations, integrated in 1866 by the substantial estates coming from another dissolution of convents, this time by order of the Italian national government. Twenty years later, in 1886, a considerable bequest came from the Sienese librarian and publisher Giuseppe Porri, comprising manuscripts, printed books, collections of engravings and drawings as well as large collections of autographs of celebrated personalities, coins, medallions and seals now moved to the Museo civico in piazza del Campo. The library’s current name was given to the institution by the podestà of Siena Fabio Bargagli Petrucci in 1932, in memory of the old literary academy of the Intronati that had had its headquarters in the Sapienza building from 1722 to 1802. Bargagli Petrucci, under whose government the building underwent a number of renovations, also donated to the library a substantial collection of advertising posters in 1935. In 1959 the City Council and the Province of Siena created a Consortium for the management of the Library. Since 1996 the library is an institution pertaining to the City Council (Comune di Siena) with the active participation of the provincial government. The Biblioteca comunale degli Intronati is also currently leading an urban library network and a network of libraries over 6 the territory of the province, comprising over forty libraries. Since the mid1990s a complex architectural renovation of the spaces of the old Sapienza has started, thanks to which the library has been allocated the spaces previously occupied by the Archaeological museum and the Istituto d’arte. The new section for trade papers, magazines and newspapers was opened in 1999, in 2001 the reading room for manuscripts and ancient books, and in 2006 a new open-shelved public library as well as a Children’s library opened in Vicolo della Sapienza. In the meantime, a rational reorganisation of the book deposits has been carried out. Finally, 2011 saw the opening of the exhibition room for drawings and engravings. The assets as a whole comprise today over 500.000 documents. 7 1. Decretum Gratiani cum Glossa ordinaria Iohannis Teutonici et Bartholomaei Brixiensis (end of the XII century-beginning of the XIII century), ms. G.V.23 Parchment; ff. III, 497 (494), III’; modern foliation (XIX century) repeating no. 481 and skipping two smaller leaves inserted after ff. 315 e 410; mm 310 × 210. Historiated initials at the beginning of the Causae and the Distinctiones, decorated initials, flourish initials, simple initials, rubricated. Restoration parchment binding The manuscript comes from the convent of S. Bernardino all’Osservanza, as confirmed by the bookplate and by Luigi De Angelis’s note recording its arrival in the library in 1811 (f. 2r). It contains the Decretum Gratiani, an essential collection of sources of canonical law edited by the jurist monk Gratianus in the first half of the XII century. In addition, the manuscript also contains the Glossa Ordinaria and some texts by Giovanni d’Andrea, doctor decretorum of the Studio bolognese in the first decades of the XIV century (in the margins to ff. 457v-461r, that is to say the Declaratio Arboris Consanguinitatis, the Declaratio Arboris Affinitatis and the Summa de sponsalibus et matrimonio). The execution of the Decretum Gratiani can be placed around the end of the XII century in the region of northern France. Lavishly illustrated, the miniatures have been attributed to four different artists, probably from the same workshop, operating between Paris and Sens, and can be dated to the last quarter of the XII century (1170-1180). The Glossa, also the work of several artists operating north of the Alps, can be dated to the middle of the following century, while the script of the works by Giovanni d’Andrea is by an Italian hand and later still (middle of the XIV century). Bibliography Ilari 1844-1848, II, 1845, p. 200; Kuttner 1937, p. 111; Mostra di manoscritti... 1952, pp. 55-56; Rabotti 1959, pp. 95-96; Kuttner 1963, p. 535; Liotta 1964, pp. 29, 30; Melnikas 1975, passim; Mecacci 1996, pp. 25-26; E. Mecacci, G. Vailati Schoenburg-Waldenburg, in Lo Studio e i testi... 1996, p. 39 n. 1; Vailati Schoenburg-Waldenburg 1996, pp. 79-80, 94, 97-100 n. 1; L’Engle, Gibbs 2001, p. 114; Murano 2005, p. 352. Annalisa Pezzo 8 2. Miscellanea (end of the XIII century-ante 1521), ms. H.VI.31 Composite. ff. IV, 168 (2-169), III’; mm 135/207 × 89/147. Recent leather binding on boards with tooling on the boards The codex, a composite volume, gathers together five manuscripts of different age and provenance also dissimilar in layout, graphic style and format. It contains: I. Dante Alighieri, Rime (end of the XV century) Parchment; ff. I, 46 (48), I’; recent foliation in pencil including the flyleaves, accompanied by old pagination (1-91); mm 135 × 89. Gilded initial on blue background with decoration in the margin, initials highlighted in red or blue, rubricated The small codex, dating back to the late XV century, in Renaissance script, contains several rhymes by Dante. On the front cover is a XV century note, now almost totally faded: “Di Cosimo de’ Medici e degli Amici” (Belonging to Cosimo de’ Medici and His Friends). Bibliography Ilari 1844-1848, I, 1844, p. 188; Iacometti 1921, pp. 213-214; De Robertis 1966, pp. 228229 n. 368. II. Orationes et epistulae (second half of the XV century) Parchment; ff. 32 (49-80); recent foliation in pencil accompanied by modern one, erroneous; mm 200 × 133. At f. 49r gilded initial with white vine-stem with a frieze on the lower margin including the coat of arms of the Tegliacci family, gilded initials with white vine-stem on blue background with friezes on the margin ending in gold buttons (ff. 58v, 67r, 71v, 74r, 75v), rubricated The manuscript, dating back to the late XV century, used to belong to the Sienese Alessandro Tegliacci, as stated in a note written on the initial page by an unknown later owner: “Dedit mihi Alex(ande)r Tegliaccius die(?) 8 decembris 1581 atque sua humanitate donavit” (Alessandro Tegliacci kindly gave this to me as a gift on 8 December 1581) (f. 49r). The decoration on the same leaf bears the coat of arms of the Tegliacci family. Alessandro is perhaps to be identified with the scholar called by Cosimo II to be professor of Humanities of the Studio (the University) of Siena in 1609. The manuscript comprises a 10 collection of prayers and Latin epistles by several Renaissance humanists: the Oratio ad pontificem Nicolaum V by Giannozzo Manetti (ff. 49r-58r), other orationes to the same recipient by Poggio Bracciolini (ff. 58v-66v) and by Francesco Micheli del Padovano (ff. 66v-71v), the Oratiuncula ad Martinum V by Leonardo Bruni, the Florentinorum epistula ad imperatorem Federicum III and the Florentinorum epistula ad Concilium Basiliense (ff. 74r-79v). Bibliography IIlari 1844-1848, I, 1844, pp. 49-50, 111; VI, 1847, p. 487; Iacometti 1921, pp. 214-215; Kristeller 1967, II, p. 154; Hankins 1997, n. 2355. III. Tractatus de creatione mundi (end of the XIII century) Parchment; ff. 48 (81-130); recent foliation in pencil; mm 207 × 147. Watercolour drawings (ff. 81r, 82r, 83r, 84r, 85r, 86r, 87v, 89r, 90v, 92r, 93v, 94v, 95v, 96r, 97r, 98r, 99r); decorated initials, flourish initials; initials with red highlights or with yellow watercolour, rubricated The codex, which contains a Tractatus de creatione mundi from the Book of Genesis, followed by a narration of the Passion of Jesus Christ (ff. 99r-128v), is one of the most significant examples of late XIII century Sienese illumination. The pictures, partly watercolour drawings partly proper illuminations, were made by an extremely refined Sienese artist, heavily influenced by Transalpine miniaturists and active from around 1290 through the following decade. The illustrations, sketched by a fast, concise hand, stand out for their strikingly smooth style, unusual in the Sienese production of the time, a quality matched by the spontaneity of the narration and an uncommonly flowing hand. The landscape details make remarkable use of spatial illusionism, a sign of the author’s awareness of Duccio’s innovations. For the series illustrating episodes from the Creation and the progenitors’ life, Luciano Bellosi suggested an identification of the anonymous miniaturist with Guido di Graziano, the author of the 1280 Biccherna tablet (Siena, Archivio di Stato, n. 7). Bellosi also traces back to Guido a considerable group of works, among which the dossal of St Peter (Siena, Pinacoteca Nazionale), stylistically very consistent with the illustrations of this codex. Ada Labriola, on the other hand, envisions a later training of our artist within Guido’s workshop, on the basis of his more modern narrative style, clearly aware of Cimabue’s and Duccio’s innovations. Labriola also recognises the hand of this miniaturist (known as the Master of the Tractatus de creatione mundi) as being different from the very similar one of the author of a Crucifixion with Virgin and St John and 11 of an illuminated initial (ff. 99r-v) decorating the Passio Iesu Christi composita ex quattuor evangelistis (Maestro of the Duecento of the Dominican Legendary). Bibliography Ilari 1844-1848, V, 1846, p. 28; Iacometti 1921, pp. 215-216; Degenhart, Schmitt 1968, I/I, pp. 21-23; Conti 1979, p. 27 n. 54; Ciardi Dupré Dal Poggetto 1981, p. 65; G. Chelazzi Dini, in Il gotico a Siena... 1982, 82-84 n. 22; Bellosi 1985, p. 40 n. 6; Bellosi 1991, pp. 17-28; La miniatura senese... 2002, pp. 26, 35, 37, 40, 41, 44, 63, 64, 267, 272; F. Mori, in Duccio... 2003, pp. 104-107 n. 16. IV. Gabriel Volaterranus, Carmen de profectione Magorum (post 1460) Parchment; ff. 13 (131-143); recent foliation in pencil accompanied by a modern foliation, erroneous; mm 206 × 137. Gilded white vine-stem initial with lapis frieze in the inside and lower margin, comprising the Piccolomini del Testa coat of arms, rubricated This XV century manuscript, in Renaissance script, contains a poetical composition (De profectione Magorum adorare Christum et de innocentibus interfectis ab Herode) by a “Gabriel Volaterranus”. The author of the poem is in all likelihood identifiable with Gabriello Zacchi da Volterra, the archpriest of the cathedral, who came from an a culturally refined background and died at thirty-three in 1467 (Anton Filippo Giachi, Saggio di ricerche sopra lo stato antico e moderno di Volterra..., in Firenze 1786, nella stamperia di Pietro Allegrini alla Croce Rossa, p. 155). The work is dedicated by the author to Tommaso del Testa Piccolomini, Pius II’s secret assistant (f. 132r), to whom the pope had granted the privilege of kinship to the Piccolomini family. In 1460 Tommaso was also awarded the title of imperial counselor by Federico III, with the honour of adding the imperial eagle to his coat of arms; subsequently he was made the bishop of Sovana first and Pienza later (Isidoro Ugurgieri Azzolini, Le Pompe sanesi, I-II, in Pistoia, nella stamperia di Pier’Antonio Fortunati, 1649, I, p. 205; Girolamo Gigli, Diario sanese..., I part, second edition, Tip. dell’ancora, Siena 1854, p. 526). The presence of the imperial eagle in Testa Piccolomini’s coat of arms within the decoration of the codex (f. 132r) suggests the year 1460 as a plausible post quem for the dating of the manuscript. José Ruysschaert attributed the illuminated decoration, with its white vine-stem motifs, to Gioacchino de’ Gigantibus, active in the 1460s within Pius II’s cultural circle. Bibliography Iacometti 1921, pp. 216-217; Kristeller 1967, II, p. 154; Ruysschaert 1968, p. 268. 13 V. Lucianus Samosatensis, Dialogi deorum, translation by Livio Guidolotto with the title Deorum dialogi decem (1518-1521) Parchment; ff. II, 24 (144-169); recent foliation in pencil including I-II, white; mm 228 × 146. Illuminated page framed by a frieze bearing pope Leo X’s emblem (f. 151r), historiated gilded initial with flowery frieze in the inside margin (f. 146r), gilded initials with phytomorphic decoration and a small frieze at ff. 151r, 153v, 155v, 158r, 159v, 161v, 163v, 165r, 167v, 168v, rubricated The manuscript contains ten of Lucianus’ dialogues in Livio Guidolotto’s (or Guidalotto, or Guidalotti) Latin version. Livio, a Classics scholar from Urbino, was Leo X Medici’s apostolic assistant, and he dedicates his translation to the pope himself in an introductory epistle of 1518 (“Romae, Idibus maii MDXVIII”; f. 150v). This year is the terminus post quem for the work, to be placed no later than 1521, the year the pope died. Giovanni de’ Medici’s emblem, with the beam accompanied by the letter “N” and the motto “Suave” as it stood even before he became pope Leo X, is inserted in the decoration within the codex. The Medici coat of arms is also present, crowned by the papal insignia and the symbol of the Medici, a diamond ring with a white, a green and a red feather and the motto “Semper”. The same emblems have been found in a group of codices in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in Florence which were probably commissioned by Leo X (see Angela Dillon Bussi, La biblioteca medicea laurenziana negli ultimi anni del Quattrocento, in All’ombra del lauro. Documenti librari della cultura in età laurenziana, edited by Anna Lenzuni, Silvana, Cinisello Balsamo 1992, pp. 135-148; p. 138). The librarian Luigi de Angelis was responsible for the publication of the text of the manuscript in Siena in 1823 (Ioanni Baptistae Zannonio... hos tantum decem quos inter Luciani Samosatensis Deorum Dialogos Livius Guidoloctus Urbinas... selegit...), with the publisher Onorato Porri. De Angelis praises the elegance of the illuminations, with particolar reference to the portrait in the dedicatory initial, believed to depict an effigy of Lucianus, and suggests an attribution to Raffaello. A review of the edition published in the “Effemeridi letterarie di Roma” puts forward the hypothesis that Guidolotto’s dedication of the caustic dialogues to the pope had not been accepted. As a result, the work remained unpublished for a very long time. The existence of the manuscript had actually already been 14 recorded at the beginning of the XVIII century in the collection of the Sienese scholar Uberto Benvoglienti, later bequeathed to the Biblioteca comunale. Bibliography Ilari 1844-1848, II, 1845, p. 11; Iacometti 1921, pp. 217; Kristeller 1967, II, p. 154. Annalisa Pezzo 15 3. Guido de Baysio, Lectura super Decreto sive Rosarium (beginning of the XIV century), ms. K.I.8 Parchment; ff. I, 316, I’; modern foliation (XIX century); mm 470 × 290. Decorated pages (ff. 88r, 102v, 132v, 134v, 137v, 148r, 151r, 153v, 220r, 221v, 225r, 232r, 245r, 251r), historiated initials, decorated by wide friezes on the margins, flourish initials, rubricated. Paper binding on boards, leather spine, cornerpieces The codex, made in Bologna, comes from the Chapter Library of Siena. The original title of the manuscript is Lectura super Decreto, but it is known as Rosarium Decretorum, since it contains the extensive comments to Gratianus’s Decretum that the canonist Guido da Baisio (Bologna 1246/1256-1313) completed around the year 1300. The illuminations, dating back to the third decade of the XIV century, are the work of two separate, important Bolognese artists, one stylistically close to the so-called Primo Maestro di San Domenico (First Master of St Dominic), the other identified as the Sesto Maestro di San Domenico (Sixth Master of St Dominic). The codex is mutilated of the first leaf, which must have contained an illumination. The end of the 157 sections that comprised the work, divided according to the pecia system, is indicated in the margins. The devotional engravings and the oriflamme containing St Bernardino’s monogram of the name of Jesus decorating the metal corners of the binding seem to indicate that the manuscript possibly belonged to the Opera del Duomo. Bibliography Ilari, 1844-1848, II, 1845, p. 204; D’Ancona 1904, p. 379; Mostra dell’antica arte... 1904, p. 143 n. 11; Venturi 1906, pp. 1008-1009; Destrez, Chenu 1953, p. 322; Conti 1979, p. 70; De Benedictis 1979, p. 63; Soetermeer 1990, p. 351; Mecacci 1996, p. 29; E. Mecacci, G. Vailati Schoenburg-Waldenburg, in Lo Studio e i testi... 1996, p. 41 n. 3; Vailati SchoenburgWaldenburg 1996, pp. 81-82, 107-110 n. 3; Murano 2005, p. 410; Mecacci 2007, p. 308. Annalisa Pezzo 16 4. Psalterium-Hymnarium (first quarter XV century), ms. U.II.12 Parchment; ff. I, 433 (435), I’; modern foliation (XIX century) including the flyleaves, mm 143 × 102. Pages decorated with foliage friezes (ff. 8r, 86r, 262r, 390r); historiated initials on gilded background with extensions in the margin (ff. 106v, 121v, 287v, 205v, 211r, 219v, 284r, 338r, 347r, 359v), decorated initials, flourish initials, rubricated. Original leather binding on boards with clasps The small codex arrived at the Library after the Napoleonic dissolutions, on 18 January 1811, according to the note on the front flyleaf by the librarian Luigi de Angelis. It came from the Osservanza convent on the Capriola hill, near Siena, where Bernardino Albizzeschi (St Bernardino of Siena) had stayed. Traditionally, it was believed to be the breviary used by Bernardino himself and had been an object of cult in the convent, kept in the saint’s cell until 1685 and later in the sacristy. As Albizzeschi’s hand is indeed recognisable in some annotations in the margins (ff. 2r, 6v, 16r, 82r), this codex can be identified as the “portable breviary” mentioned in the inventory of the saint’s personal possessions carried out in the convent on 15 June 1444, immediately after his death. The manuscript, dating back to the first quarter of the XV century, was presumably made in Siena, also because the calendar bears notice of the celebration of St Ansano, the patron saint of the town. The decoration was probably carried out by a single miniaturist, working closely with the scriptor or immediately afterwards, as confirmed by the consistency of the iconographic material with the content. The lavish illuminations feature gold leaf decoration and punching. Attached to the breviary is a Vita Beati Francisci Edita a Frate Bonaventura (Life of the Blessed Francis Edited by Frate Bonaventura) (ff. 427rb-432rb). Bibliography Ilari 1844-1848, V. 1846, p. 224; Pacetti 1936, p. 521; Mostra Bernardiniana... 1950, p. 34; L. Simonato, in Le arti a Siena... 2010, pp. 526-527 n. G.6. Annalisa Pezzo 18 5. Missale romanum (1427 June 8-1428 March 29), ms. X.II.2 Parchment; ff. I, 347, I’; modern foliation (XIX century); mm 357 × 265. Illustrated page at f. 162v, decorated page (f. 7r), historiated and decorated initials, rubricated. Modern leather binding on boards Missal commissioned by Antonio Casini after he was appointed cardinal in 1426, as per the colophon, where the scribe Antonio di Angelo da Sansepolcro states that he made it between 8 June 1427 and 29 March 1428, ff. 344v-345r). Casini was a bibliophile and a committed art enthusiast also responsible for comissioning Masaccio’s Madonna del Solletico. His coat of arms is often repeated in the decoration, more specifically appearing in the Crucifixion scene (f. 162v) in which the cardinal himself, kneeling before the Cross, is depicted with the Madonna, St John the Evangelist and St Magdalene. The codex arrived at the Library in 1761 together with other Latin manuscripts and books from the Opera della Metropolitana. Although there are no works comparable to this codex within the Sienese environment, its origin is clearly indicated by the presence of St Cerbone, the patron saint of Massa Marittima. Its illuminated decoration is ascribable to a single artist, whose identity is still unknown (the attribution to Nicola di Ulisse da Siena, suggested by Chelazzi Dini, has found no confirmation). There is no agreement on the possibility he might be a Sienese artist, either, even though the northern-Italian and French influences visible in his work could be explained by an exposure to the works of Jacopo della Quercia. The late-Gothic elements clearly present in his style together with the expressiveness and sentimentality of his figures point towards the hypothesis of a Northern Italian artist working in Siena. Two breves by will of the cardinal Juan de Carvajal, dated 9 September 1353, are transcribed at the end of the codex, granting indulgences to those who prayed before the chapel of St Maria delle Grazie and the altar of St Bernardino in the Cathedral of Siena (f. 346r). Bibliography Della Valle, 1785, p. 245; Ilari 1844-1848, V, 1846, p. 73; Ebner 1896, p. 257; Lusini 1939, p. 258; D’Ancona, Aeschlimann, 19492, p. 11; Mostra storica... 1953, p. 247 n. 386; Salmi 1956, p. 21; Rotili 1968-1969, II, 1969, p. 21; Van Os 1969, p. 49; Chelazzi Dini 1977, pp. 206-209; Inventario dei manoscritti... 1978-1986, I, 1978, pp. 11-18 n. 3; G. Garosi, G. Chelazzi Dini, in Il gotico a Siena... 1982, pp. 372-374; Sani 1982, pp. 495-496; Ciardi Dupré Dal Poggetto 1984, pp. 129-130; Inventario dei manoscritti... 2002, I, pp. 16-20 n. 3; Bollati 2006, pp. 70-80; L. Simonato, in Le arti a Siena... 2010, pp. 118-119 n. A. 40. Annalisa Pezzo 20 21 6. Antiphonarium known as Comunella de’ santi (1442) with later additions (second quarter of the XV century), ms. G.I.8 Parchment; ff. I, 213; modern foliation (XVIII century) recently integrated in pencil; mm 594 × 405. Historiated initials (ff. 1r, 4r, 18v, 25r, 40r, 44v, 47r, 62v, 70v, 85v, 96r, 118r, 118v, 149r, 156v, 160r, 161r, 162r, 162v), decorated initials, flourish initials, rubricated. Modern leather binding on boards, with cornerpieces and central boss This antiphonary was transferred to the town library in 1811 from its place of origin, the Augustinian hermitage of San Salvatore in Lecceto near Siena: a provenance confirmed by the coat of arms in the frieze on folio 4r. By virtue of its specific liturgical function the antiphonary, designed for the use of the hermitage community, contains both the daytime and the nocturnal services. The documentary sources record it as “Comunella de’ Santi” (Company of Saints) from the first section Commune sanctorum et proprium. It was illuminated in 1442 as part of an extensive artistic programme within the hermitage promoted under the priors Bartolomeo Tolomei and Girolamo Buonsignori. This phase of growth was ratified in 1446 thanks to a bull by Pope Eugene IV, which granted Lecceto independence from the Vicar General, placing it at the head of a vast network of hermitages. In this regard it has been pointed out how the peculiarities of the iconography, closely linked to the liturgical content, denote a specific visual programme, especially created for the Lecceto community. The artist Giovanni di Paolo was immediately and beyond question identified as responsible for the completion of most of the illuminations. These are mainly historiated and decorated initials as well as a depiction of the “Triumph of Death” placed at the beginning of the service for the dead (f. 162r). This allegory of Death is one of the artist’s most celebrated miniatures: Death on a charging black horse is about to strike a wounded man for the second time with an arrow, against the backdrop of a thickly wooded landscape evoking the secluded atmosphere of the hermitage. In this manuscript the Sienese painter brings to fruition his extraordinary ability to render narrative scenes with striking originality. The other illustrations (five initials, of which four historiated with a Marian subject and one decorated) belong to a different hand in both technique and style, and are the work of an extremely accomplished anonymous master who has been variously thought to belong to the Sienese school (sometimes sug- 22 23 gesting the name of Priamo della Quercia, other times that of Domenico di Bartolo), the Umbrian school and the Po valley school. The manuscript contains an XVIII century update (ff. 180-213r) following the canonization of new Augustinian saints. Bibliography Ilari 1844-1848, V, 1846, p. 70; Milanesi 1850, pp. 309-311; D’Ancona 1904, pp. 377-386; Mostra dell’antica arte... 1904 p. 151; Berenson 1932, pp. 248, 433; Mostra storica... 1953, pp. 248-249; Salmi 1956, pp. 200-221; Diringer 1958, p. 337; Samek Ludovici 1966, pp. 31-33; Vailati Schoenburg Waldenburg 1981, p. 18; G. Garosi, G. Chelazzi Dini, in Il gotico a Siena... 1982, pp. 364-368 n. 131; Boskovits 1983, pp. 259-276; Ciardi Dupré Dal Poggetto 1984, pp. 131, 135, 138, 142, 144; Strehlke, in Christiansen, Kanter, Strehlke 1989, pp. 194-203 n. 30; Vailati Schoenburg Waldenburg 1990, pp. 331, 333, 383-399, 489-501; Vailati Schoenburg Waldenburg 1992; Wilson 2001; Bollati 2006, pp. 103-105; L. Simonato, in Le arti a Siena... 2010, pp. 542-543 n. G.13. Annalisa Pezzo 24 7. [Niccolò di Giovanni di Francesco di Ventura], La sconfitta di Monte Aperto (1442-1443), ms. A.IV.5 Chartaceous; ff. III, 30 (3-32), I’; recent foliation in pencil on the top right margin, including the anterior flyleaves and accompanied by the original one (1-25), erroneous; mm. 360 × 245. Wide gouache miniatures on ff. 1r-5v e 7r-27v, depicting scenes strictly relating to the text (at times with original captions relating to the identity of the depicted characters), decorated initial at f. 3r, flourish initials, rubricated. Restoration leather binding with decorations engraved on the boards, bosses, cornerpieces and clasp The manuscript originally belonged to the Carmelite father Giovan Battista Caffardi and was transferred from its first location in the convent of S. Niccolò in Siena to the library in the XVIII century by will of the Grand Duke of Tuscany Pietro Leopoldo, as noted by the librarian Luigi De Angelis on 20 March 1810 (f. 1r-v). The manuscript is an illustrated account of the events relating to the famous battle of Montaperti, also mentioned by Dante in the Divina Commedia, which took place on 4 September 1260. The battle resulted in the victory of the armed faction of the Ghibellines, supporting the Holy Roman Emperor and led by Siena, over the Guelphs, supporting the pope and led by Florence. The manuscript is written and illustrated throughout by Niccolò di Giovanni di Francesco di Ventura da Siena, who signed it stating that he completed the text on the first of December 1442 and the pictures in the following year (ff. 27r-v). We hold little information about him other than his name, recorded since September 1402 and appearing among the members of the Painters’ Guild in 1428, and his death on 1 April 1464. It is generally agreed that the text is the result of an elaboration of the “myth” of Montaperti, dating from at least a century earlier, and that it was copied from one or more previous accounts, perhaps with insertions of further facts and information gathered from secondary sources. The illustrations, still bearing XIV century stylistic traits, were also in all likelihood reproduced from older models. In the absence of contemporary records of the battle, this very popular account represents a precious historical source, thanks to its accuracy and to the richness of its illustrations. We know of several manuscript copies of it from the XVI to the XVIII century, while Giuseppe Porri published a printed edition, integrated with other manuscripts, in 1844. William Heywood published an English translation of excerpts from this edition in his Our Lady of August and the Palio of Siena (Siena 1899, pp.13-28). 26 The lively miniatures in a flowing hand (made even smoother by the use of pen and ink and gouache) are laid out below the text, often in scenes occupying two facing pages and accurately depicting the facts narrated in the text down to the detail. A letter, now in a separate location, was originally attached to the manuscript: it belonged to count Giordano d’Anglano, Manfredi’s deputy in Tuscany, podestà of Siena and captain of a division of the Ghibelline army in the battle of Montaperti. At ff. 28r-32r are later historical records by several different hands, relating to events of the XVI and XVII centuries. Bibliography Ilari 1844-1848, VI, 1847, p. 141; G. Porri, in Il primo libro... 1844, pp. XXII-XXV; Degenhart, Schmitt 1968, pp. 321-322, tavv. 239-240; Inventario dei manoscritti... 1978-1986, I, 1978, pp. 256-260 n. 114; Ciardi Dupré Dal Poggetto 1984, p. 132; Inventario dei manoscritti... 2002, I, pp. 155-158 n. 114; A. Cavinato, in Le arti a Siena... 2010, pp. 580-581 n. G. 30. Annalisa Pezzo 27 8. Missale Romanum (first half of the XV century), ms. G.V.7 Parchment; ff. II, 194; modern foliation (XIX century); mm 248 × 182. Illustrated page at f. 92v, historiated initial on gold background and frieze on the 4 margins at f. 7r, flourish initials, capital letters with yellow highlights, rubricated. Old binding on boards with spine in restoration leather This manuscript is decorated by two miniatures only: a historiated initial with Christ Blessing on the first leaf of the Proprium (Proprium de tempore) (f. 7r) and a full-page illustration placed before the consecration canon, representing the Crucifixion with St John the Evangelist and the Madonna (f. 92v). It comes from the Opera del Duomo di Siena, as confirmed by the shelf mark on the inside front cover. The miniatures take their inspiration from monumental pictorial models: for example, the frame around the Crucifixion belongs to a tradition of wall painting dating back to Simone Martini. This, together with their placement as formally independent from the text, suggests that the miniaturist worked autonomously from the scribe. The profile that emerges is that of an artist not linked to the activity of a scriptorium and as such identifiable, on the basis of stylistic comparisons, with Stefano di Giovanni known as Il Sassetta, who is not recorded as having worked as a miniaturist. This assumption is corroborated by the unusual iconography of the Crucifixion with St John is on the left and the Virgin, the opposite to their customary positions. This attribution has been widely accepted, although uncertainty remains as to the period of execution on which opinions vary. Comparisons with Sassetta’s triptych of the Wool Guild would place the Missale after the second half of the 1420s, while stylistic references to the cross of St Martin, whose arms are in the Chigi Saracini collection in Siena, point towards the years 1435-1440; lastly, others suggest the period between 1440 and 1442 (Borgo Sansepolcro altarpiece). Bibliography Ilari 1844-1848, V, 1846, p. 72; G. Garosi, C. Volpe, in Il gotico a Siena... 1982, p. 385-387; Ciardi Dupré Dal Poggetto 1984, pp. 133-137, 145; K. Christiansen, in Christiansen, Kanter, Strehlke 1989, pp. 102-104 n. 5; L. Simonato, in Le arti a Siena... 2010, pp. 522-523 n. G. 4. Annalisa Pezzo 30 9. Breviarium fratrum Minorum secundum consuetudinem Romanae Curiae (third quarter of the XV century), ms. X.IV.2 Parchment; I, 520; recent foliation in pencil; mm 315 × 230. Decorated pages (ff. 1r-6v, 7r, 8r, 79r, 100r, 120v, 148r, 394v, 435r), historiated initials, decorated initials on a gilded background with flowery friezes in the margins, flourish initials, rubricated. Antique binding in red velvet on boards, on the boards silver rosettes, five niellos and clasps This breviary, originally belonging to the Clarisse nuns of Maggiano, was moved to the Library on 10 June 1811 from the monastery of St Clare in Siena, according to a note by the librarian Luigi De Angelis (f. 1v). The codex is preserved in a coeval wooden binding lined in red velvet with twelve silver rosettes and five nielli on each side (with the Saints Francis, Peter, Paul, John the Baptist, Bernardino of Siena on the front and Claire, Ludwig, Anthony, the Annunciation Angel and the Virgin on the back). The red velvet ties attached to the front and used to keep the book closed are decorated with translucent enamel bosses with saints and the coats of arms of the Sienese families Petroni and Castellani (also reproduced inside, in the margin of f. 7r). The illuminations are mostly due to the hand of Sano di Pietro with the help of his workshop. However, the consistency of Sano’s style over the course of his career makes it difficult to establish with certainty when the illustrations were carried out. Although the consensus is to place them in the later period of Sano’s activity, between 1450 and 1480, it seems more likely that they were carried out around 1441. This theory is supported both by observations relating to style, and by the fact that in this year Ludovico Petroni – a well-known jurist and a descendant of Cardinal Riccardo Petroni who founded the convent to whom the manuscript originally belonged – was appointed Roman senator by pope Eugene IV. The presence of Ludovico’s namesake St Ludwig of Toulouse in one of the enamels decorating the binding provides further evidence in favour of this theory. The miniatures stand out for their refreshing inventiveness and liveliness of narrative, particularly in the scenes illustrating the months of the Kalendarium which describe the various seasonal tasks inside the convent. The breviary is preceded by a calendar (ff. 1r-6v) as well as by a liturgical psalter and a hymnal (ff. 7r-75r). Bibliography Ilari 1844-1848, V, 1846, p. 68; Garosi 1953; Inventario dei manoscritti... 1978-1986, I, 1978, pp. 22-33; D. Benati, in Il gotico a Siena 1982, pp. 403-405 n. 145; Ciardi Dupré Dal Poggetto 1984, pp. 136-141; Turrini 1997, p. 52; Bollati 1998, pp. 325-326; Argenziano 2009. Annalisa Pezzo 32 10. Missale romanum (third quarter of the XV century), ms. X.II.3 Parchment; ff. 367, I’; modern foliation with recent pencil integrations; mm 410 × 287. Illustrated page (f. 181v), decorated page (f. 7r), historiated initials, decorated initials amongst which three of larger size accompanied by a wide flourish in the margins (ff. 161v, 162r, 179v), flourish initials, index. Modern leather binding on boards. The missal, presumably scripted between 1455 and 1458, was originally in the Opera del Duomo, as confirmed by the coat of arms at f. 181v and the old shelf mark on the inside front cover. The commission of the decoration is presumably due to Savinio Savini, the rector in the years 1468-1475. Savini’s name is known from the note of payment of 23 April 1471 to Liberale da Verona for the scene of the Crucifixion (f. 181v) which also bears the emblem of the Opera del Duomo. The full-page illumination is the only one by Liberale in this codex and is one of his most representative works. The artist was influenced by Girolamo da Cremona, who had recently arrived in Siena and was working beside Liberale in the cathedral. The new trends imported by the older master, such as elements from Mantegna and references to the school of Ferrara, proved popular with Sienese artists. They are visible in the treatment of the frame with its pearl-encrusted margins and in the background landscape, as well as in the typologies of human figures. Some features typical of Liberale’s already personal style – such as the acid chromatic range, the dynamic tension, the increased expressive potential of his characters – appear as even further enhanced in this miniature. The hands of a number of other artists are identifiable in the rest of the decorations. Thanks to a documentary link to some payments it has been possible to suggest a few names for them: Giovanni di Paolo and his workshop could be responsible for the initials of two sections, while the rest of the initials should be ascribed to a Battista di Fruosino, a name not connected to any other known work. The hand of another artist, identified by some with Stefano di Luigi da Milano but more probably of French-Flemish extraction, is present in the decoration of the margins of most of the sections. Bibliography Ilari 1844-1848, V, 1846, pp. 73-74; Ebner 1896, p. 257; Lusini 1939, p. 258; Mostra storica... 1953, p. 392; Del Bravo 1960, p. 25; Levi D’Ancona 1964, p. 63; Inventario dei manoscritti... 1978-1986, I, 1978, pp. 18-20 n. 4; Eberhardt 1983, pp. 93-95; K. Christiansen, in Christiansen, Kanter, Strehlke 1988, pp. 306-307; A. De Marchi, in Francesco di Giorgio... 1993, pp. 248-248 n. 40; Bollati 1998, p. 324, 325 fig. 33; Inventario dei manoscritti... 2002, I, pp. 20-22. Annalisa Pezzo 34 11. Collectarium (third quarter of the XV century), ms. X.I.3 Parchment; ff. 118 (117); modern foliation (sec. XIX) on the upper margin, omitted on the first leaf, white; mm 181 × 128. Illustrated pages (ff. 2v, 4v, 7v, 9v, 11v, 13v, 15v, 17v, 19v, 21v, 23v, 25v, 27v, 29v, 31v, 33v, 35v, 37v, 39v); gilded initials on red or blue background, pen-worked initials, rubricated (gold rubrication for ff. 2-38). Restoration binding in red leather The manuscript was bequeathed to the library by Leopoldo Feroni on 1 July 1850 (Archivio storico della biblioteca, Versamenti e doni, III, n. 90, with the note ‘said to belong to the cardinal [Giuseppe Maria] Feroni). The decorative programme comprises full-page miniatures with figures of saints inscribed within richly decorated frames bearing foliage motifs in red, blue, green and gold leaf, of Catalan-Flemish inspiration. Tammaro De Marinis attributed it to Matteo Felice, active in Naples between 1467 and 1493. Conversely, Gennaro Toscano eliminated these miniatures from Matteo’s body of work, attributing them instead to Cristoforo Majorana, active from 1472 to 1492 according to documentary sources. The codex was presumably copied in Naples by Giovan Marco Cinico, a calligrapher active in those same years at the court of Ferrante d’Aragona. Bibliography De Marinis 1962, p. 181; De Marinis 1969, pp. 93-94; Inventario dei manoscritti... 1978-1986, I, 1978, pp. 3-8 n. 2; Toscano 1996, p. 49; Inventario dei manoscritti... 2002, I, pp. 11-14 n. 1. Rossella De Pierro 36 12. Missale romanum (third quarter of the XV century), ms. X.V.1 Parchment; ff. III, 418, I’; modern foliation (XIX century); mm 303 × 228. At f. 16v an illustrated page, lavishly decorated frames at ff. 1-6, pages with frames bearing a foliage decoration, scenes (ff. 17r, 29v, 36v, 37v, 195r, 211r, 215v, 224v, 225, 260r, 271r, 277r, 288v, 292v, 308v, 315v, 328v, 333r) accompanied by decorated or historiated initials below, historiated initial (f. 183r), decorated initials alternatively on a maroon, blue or gilded background, filigree initials alternatively in blue and gold, rubricated. Old velvet binding on boards, with cornerpieces and a central boss The manuscript previously belonged to the library of Ferry de Clugny, the bishop of Tournai and later cardinal, a collector of refined taste. The provenance is confirmed by the repeated presence of De Clugny’s coat of arms and of his motto (“Bonne Pensée”) in most of the decorated folios, and by a later handwritten note. The work was probably commissioned during his years as an archbishop (1473-1483): the only full-page miniature in the codex, placed after the calendar and the liturgical rules as the title page of the missal proper (f. 16v), depicts a bishop kneeling before the Virgin enthroned with Child amongst musician and singer angels, and would logically appear to be a portrait of the commissioner. His coat of arms as well as that of the Tournai archbishopry also appear on the same folio. At Ferry de Clugny’s death the manuscript became the property of his close collaborator Jean Monissart, later also to become the bishop of Tournai. It is not clear how the codex arrived in Siena. However, in 1881 Auguste Castan reported an information he obtained from the librarian Fortunato Donati, according to which the manuscript “was in the library with the other missals that had belonged to Pius II and other members of the Piccolomini family” in the previous century. In all likelihood this codex can be identified with the one mentioned at no. 69 in the inventory of the manuscripts from the Opera del Duomo in Siena drawn up in 1761 by the librarian Giuseppe Ciaccheri, thanks to the shelf mark on the pasteboard. The miniatures illustrating the volume, of Flemish school and previously thought to be by Simon Marmion, are today attributed to Willelm Vrelant. The artist was one of the most prolific book illustrators in Bruges, where he worked from the second half of the XV century to his death (1481), although he is best known for the work he produced for the court of Burgundy. 38 Bibliography Ilari 1844-1848, V, 1846, p. 73; Castan 1881; Winkler 1915, p. 331; Ruysschaert 1968, p. 141; Hoffman 1969, p. 245; Inventario dei manoscritti... 1978-1986, I, 1978, pp. 256-260 n. 8; Winkler 1978, pp. 71, 99; Bousmanne 1997, p. 204 n. 16; Inventario dei manoscritti... 2002, I, pp. 30-32 n. 8. Annalisa Pezzo 39 13. Francesco Petrarca, Canzoniere, Trionfi, Venezia, [Gabriele di Pietro], 1473, O.III.36 in folio ; [188] The library copy of this Canzoniere is of particular interest not so much for the rarity of the edition, as for the illumination and for the provenance notes, which afford us a glimpse into the history of its owners and the areas of society in which they moved. At f. [a] 1r the incipit bears a simple illumination of the initial letter and a much richer and more significant one in the lower margin bearing a coat of arms. The decoration is embellished with pink, green, blue and yellow floral and foliate motifs in the background, while in the centre it bears a gilded shield with a diagonal strip of red diamonds. This coat of arms is undoubtedly identifiable with that of the Florentine family of the Bardi, well-known for their trading and banking enterprises, presumably the first owners of the volume. On the front pastedown is the copperplate ex libris of the Feroni family, with the coat of arms showing a right arm holding a sword surmounted by a lily. The Feroni family, of Tuscan origin, obtained Florentine citizenship in the XVII century and became one of the most prominent families in the Florentine aristocracy. Harder to read is the tempera illustration on the back of the front parchment guard-leaf showing a lion drinking at a fountain, three putti and a tree half in blossom and half bare with the central motto: “Per amor e non per forza” (by love and not by might). The coeval binding is in full leather on wood boards, restored, and is decorated with blind tooling, bosses and traces of clasps on the covers, with guard-leaves and pastedowns both in parchment. Only a few of the initials are illuminated, and mostly quite simply; more frequent are simple initials in blue ink. In the margins are some handwritten notes and small pointing hands. Bibliography BMC V 199; IGI 7521; ISTC ip00375000. Chiara Razzolini 42 14. Antonio Bettini da Siena, Monte Santo di Dio (Sacred Mount of God), Firenze, Niccolò di Lorenzo della Magna, 1477, M.V.15 in 4o ; [131] : ill. The edition is famous for being the first one in the world with illustrations engraved on copperplate instead of wood, as was customary in the XV and early XVI century. It contains three images: the sacred mountain that leads to God, Jesus Christ in the glory of Heaven and a three-faced Lucifer of clear Dantesque inspiration. They were engraved with a burin by the Florentine engraver Baccio Baldini (circa 1436-circa 1487) from a drawing by one of the greatest artists of Renaissance Florence, Sandro Botticelli (circa 1444-circa 1510), who also engraved the more renowned chalcographies that accompanied the 1481 edition of Dante’s Commedia, printed by Niccolò di Lorenzo della Magna (see P.I.27). The Jesuit Antonio Bettini (Siena 1396-1487), later the bishop of Foligno, was the author of a number of devotional works, the most important being the present Monte santo di Dio, written in Vulgar Latin, a guide to the ascetic journey towards religious rapture. Bibliography BMC VI 626; GW 2204; IGI 711; ISTC ia00886000; Sander 452. Sara Centi 43 15. Dante Alighieri, La Commedia, with comment by Cristoforo Landino, Firenze, Niccolò di Lorenzo della Magna, 1481, P.I.27 Preceding the text: Cristoforo Landino, Apologia di Dante e descrizione di Firenze; Vita di Dante; Origine della poesia; Forma dell’Inferno (Apology of Dante and a description of Florence, Life of Dante; The Origins of Poetry; The Shape of Hell). Marsilio Ficino, Ad Dantem gratulatio (In Praise of Dante) in folio ; [372] : ill. This incunable is one of the oldest printed books with copperplate illustrations in Europe, together with the edition of Monte Santo di Dio by Antonio Bettini published by Niccolò di Lorenzo della Magna in 1477 (see M.V.15) Twenty illustrations accompany the first nineteen cantos of the Inferno. The copy in the library collection still has eighteen of these extraordinarily well preserved engravings, accompanying cantos I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, XI, XII, XIII, XIV, XV, XVI, XVII, XVIII, XIX of the Inferno; the first and second one printed directly on the text, the others on glued paper strips. The pioneering technique of copperplate engraving was still in its infancy at this time and technical problems were common, which means that a large number of the copies of this work owned by other Italian and foreign libraries rarely boast the complete set of images. The intaglios of the illustrations are attributed to Baccio Baldini, while the drawings to Sandro Botticelli (see. M.V.15). The false guard-leaf of the volume bears the copperplate engraving of the Feroni family ex libris, with the coat of arms bearing a right arm holding a sword, surmounted by a lily (see also O.III.36). The binding of this copy is in full leather on pasteboard, with blind and gilded tooling and gilded title on the spine. Eighteen bookmarks in blue fabric survive, glued to mark the position of the engravings. A number of handwritten notes in the margins are present in the volume, especially in the first sections. Bibliography BMC VI 628; GW 7966; IGI 360; ISTC id00029000; Sander 2311. Chiara Razzolini 44 16. Giuliano da Sangallo, Taccuino senese (Sienese sketchbook) (circa 14901516), ms. S.IV.8 Parchment and chartaceous (chart. f. 52); ff. II, 53 (52), II’; modern foliation (XVIII century) omitted on the first leaf, traces of the ancient numbering are sometimes visible, mm 180/150 × 120/100. At ff. 2v-52v architectural, sculptural and decorational drawings. Modern binding in green Morocco leather with boards decorated with a golden frame with floriate motifs and spine decorated in gold tooling. At f. [1]r a note in the hand of the librarian Giusepppe Ciaccheri providing information on Giuliano’s date of death, at the bottom Ciaccheri’s signature. At f. 1r stamp of the Biblioteca comunale. At ff. 1v-2r are some glue-making recipes in a XVI century hand not ascribable to Giuliano The so-called ‘Sienese sketchbook’ of the famous architect and engineer Giuliano da Sangallo (Florence 1445-1516) was originally in the library of the scholar Giovanni Antonio Pecci. The librarian Giuseppe Ciaccheri, a committed and passionate collector who enriched the library’s collection with works of art of outstanding quality, acquired it in 1784 (his note of ownership is on the recto of the first leaf ). Together with the Codice Barberiniano (Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Barb. Lat. 4424), the sketchbook bears witness to the architect’s prolific drawing production, and provides us with a precious source of knowledge on his work. The small format and the style of the drawings indicate that the codex had the function of personal study and work tool. Extremely varied, the book comprises sketches, mostly with an architectural subject and often accompanied by measurements and technical notes, ideas for projects (such as the one for the dome of St Mary in Loreto), drawings of machine and artillery pieces, many copies of classical sculptures, studies of monuments observed in the course of travels and stays in Italy and France (amongst which are triumphal arches and the Colosseum), copies of reliefs, drawings of decorations (panoplies, grotesques, frames) and even some sketches of capital letters from public inscriptions. Giuliano also appears to have had a significant interest in medieval architecture, as attested, for instance, by the sketches of a number of buildings in Pisa and the Tower of the Asinelli in Bologna. Worth mentioning is the leaf with the elevation of the cappella Piccolomini in the Cathedral of Siena, dating back to one of his stays in this city (f. 20r). The sketchbook also contains the floor plans for a building for the new Sapienza of Siena (f. 20v, 21r, 28v, 29r), which, thanks to an inscription, we are able to link to Cardinal Francesco Piccolomini’s resolution, between 1492 46 and 1493, to build a new structure in addition to the already existing Sapienza, located since 1415 in the venue previously occupied by the hospital of the Misericordia, where the library currently is. The issue of the nature of these sketches is as yet unresolved: some see them as drawings for the renovation of the existing building, others think they were the designs for a new building. A drawing by the hand of Giovanni Antonio Pecci with the cross-section of the Sapienza building, based on Sangallo’s original plans, is inserted in the codex. The sketchbook provides a mirror to Giuliano da Sangallo’s multi-layered, indepth artistic culture, as well as bearing witness to his relentless, intense study and direct practice of classical models as an integral part of his architectural research. The drawings probably date back to the architect’s later years, from the last decade of the XV century to 1516. Bibliography Ilari 1844-1848, VII, 1848, p. 117; L. Zdekauer, in Il Taccuino senese... 1902; Borsi 1985, passim; Scalzo 2001, passim; Fattorini 2004, pp. 192-193; Bruttini 2009, p. 22; Ferretti 2009, passim. Annalisa Pezzo 47 17. Aristoteles, Politica, in Latin, translation by Leonardo Bruni and commentary by St Thomas Aquinas and Pierre d’Auvergne, Roma, Eucario Silber, 1492, M.IV.44 in folio ; [3], 254 [but 253] Copy printed on parchment. In the XV century printing a parchment edition represented a burdensome technical and financial commitment for a printer. The print run was usually restricted to the dedicatory copies that might have to be offered to the local lord or prince, to the financial backer or to the author. Eucario Silber, originally from Würzburg, was one of the most productive typographers and booksellers in Rome: between the end of the 1470s and the year 1509 he printed more than five hundred editions of great quality and value. At f. a4r is a miniature initial and a frieze decorated with grotesques along the left margin; in the centre of the lower margin is an illuminated coat of arms – silver shield with the blue cross bearing five crescents with gold highlights, surmounted by a cross and a bishop’s hat – framed by a garland, that can be referred to Agostino Piccolomini, author of the inscription at f. a1v, whose name is written in Greek along the garland. The coeval binding is in leather on wooden boards, embellished with blind and gold tooling on the boards, blind tooling also on the four raised cords on the spine; the boards also bear decorated metal bosses with traces of clasps and a golden edge. Bibliography BMC IV 113; GW 2448; IGI 841; ISTC ia01024000. Sara Centi 50 18. Hieronymus, saint, Epistolae, in Italian, Ferrara, Lorenzo de’ Rossi, 1497, M.II.18 Followed by: Lupus de Oliveto, Regula monachorum ex Epistolis S. Hieronymi excerpta, in Italian in folio ; [4], CCLXIX, [1] : ill. The edition is remarkable for its large number of xylographies, of great compositional finesse. The two large frames at the beginning, enclosing xylographed figures, were certainly taken by the printer Lorenzo de’ Rossi from the earlier edition of the work by Felice Foresti in 1497, De claris mulieribus. The edition represents a variation on an interesting bibliographical case. Several versions of this edition actually exist, in which the printer was able to replace the writing figure of St Jerome, originally in the first frame, with a dedicatory inscription to a personality of the time. In this copy, at f. a1v, the figure of the saint is replaced by a xylographed dedication to Eleonora d’Este. We have records of other copies are attested, bearing dedications addressed to Ercole d’Este (1494) or Agostino Barbadico (1495). The provenance of the volume is unknown, but it certainly reached the Public Library at the time of the Napoleonic dissolutions, thanks to the abbot Luigi de Angelis, as confirmed in the handwritten annotation at f. [*]2r: “Ad Bibliothecam pub.am transfertur di 12 Martii 1811 Aloysio De Angelis bib”. The binding is coeval, in full leather, with blind and gilded tooling on wood boards with centred gilded title and metal clasps. Bibliography BMC VI 614; GW 12437; IGI 4746; ISTC ih00178000; Sander 3404. Chiara Razzolini 52 19. Francesco Colonna, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, Venezia, Aldo Manuzio, 1499, O.III.38 in folio ; [234] : ill. An acrostic formed by the initials of the thirty-eight chapters of the two sections of the book gives us the name of the author: “POLIAM FRATER FRANCISCUS COLUMNA PERAMAVIT”. However, Colonna’s authorship of the work is not always regarded as certain, and not all the commentators are in agreement on this issue: Piero Scapecchi, for instance, maintains that Francesco Colonna is just the recipient of the dedication and that the author is actually the friar Eliseo da Treviso (see “Accademie e biblioteche d’Italia”, 51, 1983, pp. 286-98; 53, 1985, pp. 68-73). The Poliphilus as a title has always been surrounded by a mystical aura, highly collectable for being one of the rare illuminated incunables produced by the most learned of the XV century publishers: Aldo Manuzio the Elder. The elegant wood engravings illustrating Poliphilus’ love entanglements, showing an in-depth knowledge of architecture as well as of antiquities, give this book a place amongst Italian renaissance masterpieces despite the unresolved debate on their attribution. The work was published again by Aldo’s heirs in 1545, using the same xylographs. In terms of numbers, this edition is ordinary (we have records for three hundred copies globally, sixty-five of which in Italy); what makes our copy special are the annotations on the margins by a coeval hand, accompanied by extremely elegant brown ink drawings. Bibliography BMC V 561; GW 7966; IGI 3062; ISTC ic00767000; Sander 2056. Sara Centi 54 20. Artist from the circle of Baldassare Peruzzi; Baldassarre Peruzzi (?), Projects for an Arcade in Piazza del Campo, circa 1530, E.I.2, ff. 1r-6r stylus, black pencil, pen and teal ink, teal and pink watercolour, mm 410 × 534; 410 × 495; 398 × 529; 398 × 528; 370 × 517; 370 × 510 Sienese Artist, Project for a Stage Set with a City Scene, circa 1550-1575, E.I.2, f. 7r stylus, black pencil, pen and teal ink, teal watercolour, white lead, mm 405 × 554 Sienese Artist, Horatius Cocles Defends the Pons Sublicius, middle XVI century, E.I.2, f. 8r black pencil, pen and teal ink, teal watercolour, white lead, mm 400 × 550 The eight leaves, now preserved unbound, were previously part of a portfolio arrived at the library in the XIX century from Marcello Biringucci’s collection, as indicated in the sometimes damaged inscription present on almost every leaf. The group of the first six, consistent in concept, format and technique, illustrates studies for an arcade to be built in Piazza del Campo in Siena, to resemble an ancient forum. This utopian project, initially conceived within the circle of Baldassare Peruzzi and his students around the first half of the XVI century, was resumed a number of times in later years but never carried out. The drawings in question, clearly influenced by Peruzzi’s style, were traditionally attributed to Tommaso Pomarelli, a draughtsman and a handyman who also carried out Peruzzi’s ideas. They have also been linked to the activity of Lorenzo di Francesco Pomarelli (Siena 1517-in the records until 1573), who was, however, mainly known as an engineer and mostly active outside of Siena. Recently, the drawings were linked back to Balddassarre Peruzzi’s workshop: two leaves (ff. 6r and 4v) within the group have been acknowledged as being the product of a more skilful hand, making it possible to suggest the name of Peruzzi himself. The repetition of the same theme, in extremely detailed variations, would indicate that the drawings were an exercise undertaken by the apprentices in the workshop using the master’s work as a model. An overall study for the arcade that should have surrounded the Campo is in the collection of the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Siena. The two leaves originally bound at the end of the portfolio are different from 56 the others in subject and technique. The first one is a project for a theatre stage set with a city view, thought to be by a Sienese master from Peruzzi’s circle active between 1550 and 1575 circa (f. 7r). The second one depicts an episode of ancient history, Horatius Cocles defending the Pons Sublicius, and is ascribable to an artist active in the central years of the XVI century (f. 8r). Bibliography G. Fattorini, in Siena 1600... 1999, pp. 131-132; Frommel 2005, pp. 19-21; Quast 2009, passim; Sani 2009, pp. 115. Annalisa Pezzo 57 21. Oreste Vannocci Biringucci, Architecture, Fortifications and Machines (second half of the XVI century), ms. S.IV.1 Chartaceous; ff. I, 149, I’; modern foliation (sec. XVIII) recently integrated and corrected in pencil; mm 200 × 135. Ff. 1r-149v, drawings of residential and military architecture accompanied by handwritten explanations. Modern parchment binding Oreste Vannocci Biringucci’s sketchbook, acquired by the librarian Giuseppe Ciaccheri, whose signature is at f. 2r and at f. 148v, comprises groups of drawings of monuments mainly located in Florence, Rome and Naples. The sketches were gathered as source material for a proposed treatise on architecture (Trattato degli edifizi e delle fabbriche nobili del mondo, così antiche come moderne, Treatise on noble buildings and constructions in the world, ancient as well as modern) which never saw publication because of the writer’s untimely death in 1585. The issue of the attribution of the drawings is particularly contentious. Two handwritten notes at f. 2r indicate two different attributions: the first note, from the XVIII century, to Baldassarre Peruzzi, the second, of a later date, to Oreste Vannocci Biringucci. Recent studies see this body of work as the collation of three sketchbooks ascribable to three hands: the first Sallustio Peruzzi, Baldassarre’s son, the second an anonymous Sienese artist, the third Oreste Vannocci Biringucci. Ciaccheri himself would have been responsible for collating the three units in the second half of the XVIII century. However, this theory is difficult to verify as from a codicological point of view the manuscript seems sufficiently consistent. Moreover, differentiating the hands is an arduous task as the drawings were copied from other codices: on the other hand, the identification of the handwritten interventions by different hands is easier. While a conclusive investigation has not yet been carried out, Heydenreich, later followed by Lamerle, considers the sketchbook as an almost integral copy of the Lille portfolio. According to more recent studies, this sketchbook represents an important element in the comparison with the Campori codex in Modena, with a portfolio of architectural drawings previously belonging to Filippo Baldinucci, and with the afore mentioned Lille portfolio. Bibliography Ilari 1844-1848, VII, 1848, p. 119; Scaglia 1988, pp. 169-197; Scaglia 1990, pp. 25-42; D. Lamberini, in Prima di Leonardo... 1991, p. 227 (with previous bibliography); Scaglia 1992; Bruttini 2009, pp. 20-22; Mussolin 2009, p. 52; Sani 2009, pp. 118-124. Rossella De Pierro 60 22. Anonymous engraver from a drawing by Teofilo Gallaccini, View of Siena, circa 1599, F2.I.4, f. 56r burin, mm 312 × 414 Top centre “ABSCONDI NON POTEST CIVITAS SVPRA MONTEM POSITA”; bottom right “Delineabat D. TG.”; below, on two columns “Breve totius Historiae Senarum Argumentum / Orlando Malavolta Auctore...” In 1574 Orlando Malavolti published a work by the title Historia de’ fatti e guerre de li Sanesi (A History of the Facts and Wars of the Sienese) for the publisher Luca Bonetti in Siena. The volume was the first part of a project covering the history of the city from its origins to the conquest by the Medici. The work also included a view of the city from the north, author unknown, showing the urban layout prior to the modifications carried out by the Granducato from 1560. Malavolti, a geographer and an expert in map projection, was probably also responsible for the remarkably original and innovative illustrative programme. Malavolti died before he could bring the whole project to completion. The second and third parts of the series (Historia del sig. Orlando Malavolti De’ fatti, e Guerre de’ Sanesi..., in Venetia, per Salvestro Marchetti libraro in Siena all’insegna della Lupa) were edited by his sons Ubaldino e Bernardo and published in 1599, three years after Orlando’s death. A new cityscape accompanies the edition: although it clearly echoes the view of the city in the first volume in its general structure, the new map projection appears considerably updated and more richly detailed. Another main difference is also the addition of an architectural frame around the scene. The engraving bears a reference to the author of the drawing, signed with the initials “D. TG”. This monogram was used as a signature by Teofilo Gallaccini (Siena 1564-1641), a versatile, erudite writer of essays, a medical doctor and an expert in architecture and antiques. It also appears in the margins to some drawings illustrating his unpublished treatise Teoriche e pratiche di prospettiva scenografica (Theory and Practice of Stage Set Perspective; ms. L.IV.4 in the Library). The initial ‘D’ preceding the monogram stands for ‘Doctor’, an attribute that often accompanies his name in documentary sources. Gallaccini’s scholarly historical interests included an indepth research on the urban layout changes in Siena throughout the centuries, with special regard to the reconstruction of boundary walls outlines: all consistent with the profile of the author of the drawing for this engraving. The copper matrix of the view is also in the Library’s collection. 62 Bibliography Romagnoli [ante 1835], ed. 1976, VIII, pp. 752-753; Mostra dell’Antica Arte Senese... 1904, pp. 18 n. 42 (2046), 20 n. 57 (2058); Bortolotti 1983, pp. 92-93 fig. 68, p. 209 n. 7; Pellegrini 1986, pp. 94-98; E. La Spina, in L’immagine di Siena... 1999, pp. 44-45; A. Pezzo, in Siena 1600... 1999, pp. 136-138; E. Pellegrini, in Barzanti, Cornice, Pellegrini 2006, pp. 50-52 n. 39. Annalisa Pezzo 63 23. Bernardino Mei, Chigi Allegory (Hercules and Atlas Hold the Universe), 1656, S.II.5, f. 58r c; F2.I.3, c. 96r b red pencil on white paper with red tint on the verso, mm 290 × 173 etching, mm 308 × 230; bottom right “B. Mei f. 1656” The drawing, an allegory depicting Hercules and Atlas holding the Universe, is by Bernardino Mei (Siena 1612-Roma 1676), one of the most significant protagonists of the figurative arts world in Siena in the XVI century. This drawing, in red pencil, a technique the artist often used in his sketches, is the remaining fragment of a larger sheet that had been used to convert the composition into an etching. This is clear first of all for the accuracy of the details, the high definition of the scene in the smallest details, and the presence on the verso of the sheet of the typical red pencil tinting, traditionally used to transfer the drawing on the matrix before carrying out the etching by outlining the contours with a metallic edge which left marks that are also visible. The comparison with the print, also part of the Library’s collection, confirms this theory in the corresponding dimensions, the absence of significant variations and the specularity of the two scenes. This is one of the few etchings ever carried out by the Sienese painter: there are only other nine known ones, extremely limited editions, all dated or to be inscribed within a limited period, between 1653 and 1656. It confirms the close relationship that the painter enjoyed with the Sienese family of the Chigi in a crucial year for his career. 1656 was the year of Fabio Chigi’s ascent to the pontifical throne with the name of Alexander VII, an event of great consequence for the painter, called to work in Rome for the Chigi entourage, and of significant influence also on the art world in Siena. Alexander VII went on to be one of the leading forces behind the Baroque renovation of Rome, thanks to the boost he gave to architecture and the arts during his papacy. The allegorical nature of the subject, inspired by the heraldic elements of the Chigi coat of arms (the six hills, the star, the oak tree), indicate that the etching was probably taken from an unidentified pamphlet published for a dissertation. Bibliography Romagnoli [ante 1835] ed. 1976, X, p. 488; De Vesme, 1906, p. 13 n. 4; Bisogni, in Bernardino Mei... 1987, pp. 175, 185, 187 fig. 93; Gianni 1996, pp. 351; Angelini 1998, pp. 134, 136 fig. 124; S. Masignani, in Alessandro VII... 2000, pp. 367-368 n. 228; Ciampolini 2002, pp. 224-227 n. 47; Ciampolini 2003, pp. 70-71, 112; Pezzo 2009, p. 203; Ciampolini, 2010, I, p. 369. Annalisa Pezzo 64 24. Guillaume Vallet and Étienne Picart from a concept and drawing by Carlo Maratti, Chigi Allegory for Alessandro Bandinelli’s Dissertation, 1658, Stampe Gori Pannilini burin on silk satin pasted on paper, mm 385 × 558, engraving on the top; mm 555 × 558, engraving on the bottom (the whole composition mm 940 × 558) Top engraving: bottom left “Guillelmus Valet. / sculpsit Rom.”; bottom engraving: in the centre the dedication “d. o. m. / eminentissimo ac reverendissimo principi / flavio s. r. e. cardinali chisio / alexander bandinellvs f. ...” ; followed by the twenty puncta of the dissertation listed under the heading “conclvsiones ex vtroqve ivre depromptae.”. Bottom left in the scroll within the emblem “meliora latent”, on the right in the scroll within the emblem “sVccos oblita priores”, in the centre “Disputabuntur publice / senis / In Aula Comitiorum / ad mdclviii / Mense Die”. Below, on the left “Carolus Marattus inuenit et del.”, on the right “Stephanus Picart sculpsit Romae” The poster, printed in Rome by Guillaume Vallet (Paris 1632-1704) and Étienne Picart (Paris circa 1631-Amsterdam 1721) from a drawing by Carlo Maratti (Camerano 1625-Roma, 1713), was realised for Alessandro Bandinelli’s law dissertation (conclusiones), discussed in Siena in December 1658. In the case of public debates of a final dissertation for a doctoral degree (or preliminary to it, as was customary in Siena) it was common practice to print a flyer indicating the place, the day and the time of the event. These flyers, the first known examples of which were handwritten sheets dating back to the end of the XV century in Bologna, later became a typology in themselves after the introduction of printing, and their popularity greatly increased in the XVII century. The conclusiones, dedicated to celebrated personalities, initially bore the coat of arms of the object of the dedication. This feature later developed into allegorical scenes inspired by the heraldic elements in the coat of arms, often commissioned to famous artists, authors of both the drawing and the engraving. As they were designed to mark a special occasion, these posters had very limited print-runs and are today extremely rare. The silk specimen in the collection of the Biblioteca comunale degli Intronati di Siena comes from the Gori Pannilini collection, and is amongst the most representative of the genre. The use of the silk support, which makes it even more precious, means that this copy was probably one of those reserved for the most important members of the debate board, which were customarily printed on more expensive material. 66 The protagonist of the debate, Alessandro Bandinelli, was the son of Volunio, who later became a cardinal and was one of pope Alexander VII Chigi’s most closest collaborators. The long inscription accompanying the allegory, inspired by the heraldic elements in the Chigi’s coat of arms (the six hills, the star, the oak trees) states that the conclusiones are dedicated to the Cardinal Flavio Chigi, however, they are also indirectly celebrating the pope, named in the text and reproduced. The commission to an artist of Maratti’s stature and the use of engravers of Valet and Picart’s standing is testament to the prestigious position in society enjoyed by the Bandinelli family, and is justified by the eminence of the recipient of the dedication. The work, with a double matrix – the top one by Vallet and the bottom one by Picart – is an example of the prolific collaboration of the two engravers, who in 1658 had not been in Rome for long but were already well connected with the French artists in the Chigi family circle. Bibliography A. Pezzo, in Alessandro VII... 2000, pp. 171-173 n. 99 (with previous bibliography); Gady, 2002, pp. 77-78, 88-89, 98. Annalisa Pezzo 67 25. Anonymous English-speaking traveller, Sketchbook (May-June 1885), inv. 58695 Chartaceous; ff. 22; recent foliation in pencil, ff. 18-22 white; mm 266 × 355. At ff. 1r-17r are 17 architectural watercolour drawings. Binding in hammered canvas with leather spine, both boards and spine decorated by a gold keyline. On the inside front cover the label of the company that produced the sketchbook “Lechertier Barbe & Co.” and the pen inscription “vol. 9. Italy. 1885” The sketchbook, purchased by the library in 1965, contains seventeen watercolour drawings, some unfinished, with views and sketches of places visited in the course of a journey across Italy and France. Several notes in pencil in English reveal the cultural background of the anonymous traveller, and provide us with information as to the dates of the tour: from 12 May 1885 (the date on the first sheet) to the following month (the last noted date is 11 June, but it is followed by undated views of other places). The sequence of the drawings also makes it possible to figure out his itinerary: from Florence (the first watercolour represents studies of the inlaid marble decorations in the baptistery and in San Miniato) he moves to Siena, then to Prato (where the inlaid marble decorations in the Duomo capture his attention again) and back to Florence (Santa Croce). In Bologna on 25 May he studies the mullioned windows in San Petronio; two days later, the façade of Santo Stefano. Venice is the next stop, at the beginning of June, with the Duomo of Murano and San Marco, followed by Verona with the tombs of the Scala. Once in France, he visits Reims where he admires St Remy on 11 June, then moving to Laon and Amiens (the last watercolour depicts one of the side doors of the cathedral). The dates allow us to circumscribe the stay in Siena from 16 to 21 May. Besides the obvious places visited by any tour of the city – such as a side view of San Domenico, a Duomo interior, a view of Palazzo Pubblico and of Piazza del Campo on a market day – one drawing stands out, depicting an unusual view of the Palace courtyard with the staircase to Palazzo Grottanelli, today Palazzo del Capitano, with the figure of a man leaning on the balustrade. Some of the studies, accompanied by measurements and descriptive notes, illustrate decorative and architectural details; of remarkable quality those dedicated to the inlaid marble decorations in the Duomo. The last drawing in the sketchbook is an unfinished view of the city with the Duomo, probably seen from San Domenico, initially carried out on a loose sheet later glued to the back pasteboard. 68 This sketchbook represents one of the uncountable demonstrations of the popularity of Siena in Anglo-Saxon culture from the XIX century. The visits on the journey, the typology and modality of the work, the quality of the extremely elegant, accurate and smooth hand outline a profile of the unknown author as of Pre-Raphaelite taste, influenced by John Ruskin’s ideas. Ruskin was one of the most enthusiastic connoisseurs of old Sienese art, responsible for making it known and appreciated in the English-speaking art world; he visited the city many times, producing watercolours and drawings. On the trail of Ruskin’s teachings Siena became one of the most important destinations for English and American artists in search of Gothic inspiration (amongst the many illustrious visitors, Edward Burne-Jones and Charles Fairfax Murray came to Siena together in 1873). Bibliography Petrioli [undated, but 2000]. Annalisa Pezzo 69 Bibliography 1785 Guglielmo Della Valle, Lettere sanesi..., II, in Roma, presso Generoso Salomoni, 1785. [ante 1835] Ettore Romagnoli, Biografia Cronologica de’ Bellartisti Senesi dal Secolo XII a tutto il XVIII [ante 1835], 13 voll., BCS, mss. L.II. 1-13, stereotype edition, S.P.E.S., Firenze, 1976. 1844 Marcantonio Bellarmati, Il primo libro delle istorie sanesi di Marcantonio Bellarmati. Due narrazioni sulla sconfitta di Montaperto tratte da antichi manoscritti. Cenni sulla zecca sanese con documenti inediti, edited by Giuseppe Porri, Onorato Porri, Siena, 1844. Lorenzo Ilari, La Biblioteca pubblica di Siena disposta secondo le materie da Lorenzo Ilari. Catalogo che comprende non solo tutti i libri a stampa e mss. che in quella si conservano, ma vi sono particolarmente riportati ancora i titoli di tutti gli opuscoli, memorie, lettere inedite e autografe, I-IX, Tip. All’insegna dell’ancora, Siena, 1844-1848. 1850 Gaetano Milanesi, Storia della miniatura italiana con documenti inediti, Le Monnier, Firenze, 1850. 1881 Auguste Castan, “Le missel du cardinal de Tournai à la bibliothèque de Sienne”, Bibliothèque de l’École des Chartes, 42, 1881, pp. 442-450. 1896 Adalbert Ebner, Quellen und Forschungen zur Geschichte und Kunstgeschichte des Missale Romanum in Mittelalter. Iter Italicum, Herder, Freiburg, 1896. 1902 Il Taccuino senese di Giuliano da San Gallo. 50 facsimili di disegni d’architettura, scultura ed arte applicata pubblicati da Rodolfo Falb, Stabilimento fotolitografico di Rodolfo Falb, Siena, 1902. 1904 Mostra dell’Antica Arte Senese. Catalogo generale illustrato, exhibition catalogue (Siena, Palazzo Pubblico, april-october 1904), Tip. e Lit. Sordomuti di L. Lazzeri, Siena, 1904. Paolo D’Ancona, “La miniatura alla Mostra senese d’arte antica”, L’Arte, 7, 1904, pp. 377-386. 1906 Alexandre De Vesme [Alessandro Baudi di Vesme], Le peintre-graveur italien. Ouvrage faisant suite au peintre-graveur de Bartsch, Hoepli, Milano, 1906. Adolfo Venturi, Storia dell’Arte Italiana, V, Hoepli, Milano, 1906. 1908-1972 Catalogue of Books printed in the XVth Century now in the British Museum, Trustees of the British Museum, London, 1908-1972. 1915 Friedrich Winkler, “Studien zur Geschichte der niederlandischer Miniaturmalerei des XV und XVI Jahrbunderts”, Jahrbuch des Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen des Allerhochsten Kaiserhauses, 32, 1915. 1921 Fabio Iacometti, “Manoscritti e edizioni dantesche nella Biblioteca comunale di Siena (sec. XIV-XVI)”, Bullettino senese di storia patria, 28, 1921, pp. 181-237. 1925Gesamtkatalog der Wiegendrucke, edited by The Kommisssion für den Gesamtkatalog der Wiegendrucke, Hiersemann, Leipzig (then Stuttgart), 1925-. 1932 Bernard Berenson, Italian pictures of the Renaissance, at the Clarendon Press, Oxford 1932. 1934 Dionisio Pacetti, “I codici autografi di san Bernardino da Siena della Vaticana e della Comunale di Siena”, Archivum Franciscanum Historicum, 27, 1934, pp. 224-258. 1936 Dionisio Pacetti, “I codici autografi di san Bernardino da Siena della Vaticana e della Comunale di Siena”, Archivum Franciscanum Historicum, 29, 1936, pp. 215-241, 501-538. 1937 Stephan Kuttner, Repertorium der Kanonistik (1140-1234), Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Città del Vaticano, 1937. 1939 Vittorio Lusini, Il Duomo di Siena. Parte seconda, Soc. an. arti graf. S. Bernardino, Siena, 1939. 1942 Max Sander, Le livre à figures italien depuis 1467 jusqu’a 1530. Essai de sa bibliographie et de son histoire, Hoepli, Milano, 1942. 1943-1981 Indice generale degli incunaboli delle biblioteche d’Italia, I-VI (Indici e cataloghi, n. s.; 1), edited by Centro nazionale d’informazioni bibliografiche, Libreria dello Stato, Istituto poligrafico e Zecca dello stato, Roma, 1943-1981. 72 1949 Paolo D’Ancona, Erhard Aeschlimann, Dictionnaire des miniaturistes. du Moyen Âge et de la Renaissance dans les differentes contrées de l’Europe, Hoepli, Milano, 19492. 1950 Mostra Bernardiniana nel V centenario della canonizzazione di S. Bernardino, maggio-ottobre 1950. Catalogo, edited by Raffaello Niccoli, Siena, 1950. 1952 Mostra di manoscritti e incunaboli del Decretum Gratiani, Biblioteca Universitaria di Bologna, Bologna, 1952. 1953 Jean Destrez, Marie-Dominique Chenu, “Exemplaria universitaires des XIIIème et XIVème siècles”, Scriptorium, 7, 1953, pp. 68-80. Gino Garosi, “Il calendario senese di Sano di Pietro”, Almanacco dei bibliotecari italiani, 2, 1953, pp. 13-15. Mostra storica nazionale della miniatura, edited by Giovanni Muzzioli, exhibition catalogue (Roma, Palazzo Venezia), Sansoni, Firenze, 1953. 1956 Mario Salmi, La miniatura italiana, Electa, Milano, 1956. 1958 David Diringer, The Illuminated Book, its History and Production, Faber and Faber, London, 1958. 1959 Giuseppe Rabotti, “Elenco descrittivo di codici del Decretum in archivi e biblioteche italiane e straniere,” Studia Gratiana: post octava Decreti saecularia. Collectanea historiae iuris canonici, 7, 1959, pp. 69-124. 1960 Carlo Del Bravo, “Liberale a Siena”, Paragone, 129, 1960, pp. 16-38. 1962 Tammaro De Marinis, “Di alcuni codici calligrafici napoletani del XV secolo”, Italia medievale e umanistica, 5, 1962, pp. 179-182. 1963 Stephan Kuttner, “Some Gratian manuscripts with early glosses”, Traditio, 19, 1963, pp. 532-536. 1964 Mirella Levi D’Ancona, “Postille a Girolamo da Cremona”, in Studi di Bibliografia e di Storia in onore di Tammaro de Marinis, III, Stamperia Valdonega, Verona, 1964, pp. 45-104. Filippo Liotta, “Appunti per una biografia di Guido da Baisio Arcidiacono di Bologna”, Studi Senesi, 76, 1964, pp. 7-52. 1966 Domenico De Robertis, “Censimento dei manoscritti di rime di Dante”, VII, Studi Danteschi, 43, 1966, pp. 205-238. Sergio Samek Ludovici, La miniatura rinascimentale, Fabbri, Milano, 1966. 73 1967 Paul Oskar Kristeller, Iter Italicum. Accedunt alia itinera. A Finding List of Uncatalogued or Incompletely Catalogued Humanistic Manuscripts of the Renaissance in Italian and other Libraries. II. Italy. Orvieto to Volterra. Vatican City, The Warburg Institute, London, 1967. 1968 Bernhard Degenhart, Annegrit Schmitt, Corpus der italienischen Zeichnungen 1300-1450, I-IV, G. Mann, Berlin, 1968. Hendrik Willem van Os, “Schnee in Siena,” Neederlands Kunsthistorischen Jaarboek, 19, 1968, pp. 1-50. José Ruysschaert, “Miniaturistes ‘romains’ sous Pie II”, in Enea Silvio Piccolomini Papa Pio II. Atti del convegno per il quinto centenario della morte e altri scritti raccolti da Domenico Maffei, Accademia Senese degli Intronati, Siena, 1968, pp. 245-282. 1968-1969 Mario Rotili, La miniatura gotica in Italia, I-II, Libreria scientifica editrice, Napoli, 1968-1969. 1969 Edith Warren Hoffman, “Simon Marmion reconsidered”, Scriptorium, 23, 1969, pp. 243-271. Tammaro De Marinis, “Codici miniati a Napoli da Matteo Felice nel secolo XV”, Contributi alla Storia del libro italiano. Miscellanea in onore di Lamberto Donati, Olschki, Firenze, 1969, pp. 93-106. Hendrik Willelm van Os, Maria Demut und Verherrlichung in der sienesischen Malarei 1300-1450, Staatsuitgeverij, Den Haag, 1969. 1971 José Ruysschaert, “La bibliothèque du cardinal de Tournai à la Vaticane”, in Horae Tornacenses. Recueil d’études d’histoire publiées à l’occasion du VIII centenaire de la consécration de la Cathédrale de Tournai, Archives de la Cathédrale, Tournai, 1971, pp. 131-141. 1975 Anthony Melnikas, “Corpus picturarum minutarum quae in codicibus manuscriptis iuris continentur”, Studia Gratiana: post octava Decreti saecularia, 16-18, 1975. 1977 Giulietta Chelazzi Dini, “Lorenzo Vecchietta, Priamo della Quercia, Nicola da Siena: nuove osservazioni sulla Divina Commedia Yates Thompson 36”, in Jacopo della Quercia fra Gotico e Rinascimento (Proceedings of the Conference, Siena, Facoltà di lettere e filosofia, 2-5 October, 1975), edited by Giulietta Chelazzi Dini, Centro Di, Firenze, 1977, pp. 203-228. 1978 Friedrich Winkler, Die flämische Buchmalerei des XV. und XVI. Jahrhunderts, B. M. Israël, Amsterdam, 1978. 1978-1986 Inventario dei manoscritti della Biblioteca comunale di Siena, I-III, edited by Gino Garosi, La Nuova Italia, Firenze, 1978-1986. 1979 Alessandro Conti, “Problemi di miniatura bolognese”, Bollettino d’Arte, 64, 1979, pp. 1-28. Cristina De Benedictis, “Miniature Senesi del primo Trecento”, Prospettiva, 14, 1979, pp. 58-65. 74 1981 Maria Grazia Ciardi Dupré Dal Poggetto, Il Maestro del codice di S. Giorgio, Edam, Firenze, 1981. Grazia Vailati Schoenburg-Waldenburg, “La Libreria di coro dell’Eremo di San Salvatore di Lecceto”, Antichità viva, 20, 1981, pp. 12-24. 1982 Il gotico a Siena. Miniature, pitture, oreficerie, oggetti d’arte, exhibition catalogue (Siena, Palazzo Pubblico, 24 July-30 October 1982), Centro Di, Firenze, 1982. Bernardina Sani, “Artisti e committenti a Siena nella prima metà del Quattrocento”, in I ceti dirigenti nella Toscana del Quattrocento (Proceedings of the Conference, Firenze, 10-11 December 1982; 2-3 December 1983), Comitato di studi sulla storia dei ceti dirigenti in Toscana-Papafava, Firenze, 1982, pp. 485-507. 1983 Lando Bortolotti, Siena, Laterza, Roma-Bari, 1983. MiklÓs Boskovits, “Il Gotico senese rivisitato. Proposte e commenti su una mostra”, Arte Cristiana, 71, 1983, pp. 259-276. Hans-Joachim Eberhardt, Die Miniaturen von Liberale da Verona, Girolamo da Cremona und Venturino da Milano in den Chorbüchern des Doms von Siena. Dokumentation, Attribution, Chronologie, Wasmuth, Berlin, 1983. 1984 Maria Grazia Ciardi Dupré Dal Poggetto, “La libreria di coro dell’Osservanza e la miniatura senese del Quattrocento”, in L’Osservanza di Siena. La basilica e i suoi codici miniati, Monte dei Paschi di Siena, Siena, 1984, pp. 111-154. 1985 Luciano Bellosi, “Su alcuni disegni italiani tra la fine del Due e la metà del Quattrocento”, Bollettino d’arte, 70, 1985, pp. 1-42. Stefano Borsi, Giuliano da Sangallo. I disegni di architettura e dell’antico, Officina, Roma 1985. 1986, Ettore Pellegrini, L’iconografia di Siena nelle opere a stampa. Vedute generali della città dal XV al XIX secolo, Lombardi, Siena 1986. 1987 Bernardino Mei e la pittura barocca a Siena, exhibition catalogue (Siena, Palazzo Chigi Saracini, 1987), edited by Fabio Bisogni, Marco Ciampolini, S.P.E.S., Firenze, 1987. 1988 Gustina Scaglia, “Drawings of Forts and Engines by Lorenzo Donati, Giovanbattista Alberti, Sallustio Peruzzi, The Machine Complexes Artist, and Oreste Biringuccio”, Architectura. Zeitschrift für Geschichte der Baukunst/Journal of the History of Architecture, 18, 1988, pp. 169-197. 1989 Keith Christiansen, Laurence B. Kanter, Carl Brandon Strehlke, La Pittura Senese nel Rinascimento. 1420-1500, with a text by Mario Ascheri, exhibition catalogue (New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 20 Dicember 1988-19 March 1989), Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena, Siena, 1989. 75 1990 Gustina Scaglia, “Drawings of Cinquecento Palaces and Palace-fort, a church by Lorenzo dei Pomarelli, and a chapel for the Confraternita di San Luca in Rome”, Palladio, 6, 1990, pp. 25-42. Frank P. W. Soetermeer, De pecia in juridische handschriften, Elinkwijk, Utrecht ,1990. Grazia Vailati Schoenburg-Waldenburg, “La libreria di coro di Lecceto”, in Lecceto e gli eremi agostiniani in terra di Siena, Monte dei Paschi di Siena, Siena, 1990, pp. 331-572. 1991 Luciano Bellosi, “Per un contesto cimabuesco senese: b) Rinaldo da Siena e Guido di Graziano”, Prospettiva, 62, 1991, pp. 15-28. Prima di Leonardo. Cultura delle macchine a Siena nel Rinascimento, exhibition catalogue (Siena, Magazzini del Sale, 9 June-30 September 1991), edited by Paolo Galluzzi, Electa, Milano, 1991. 1992 Gustina Scaglia, Francesco di Giorgio. Checklist and History of Manuscripts and Drawings in Autographs and Copies from ca. 1470 to 1687 and Renewed Copies (1764-1839), Lehigh University Press-Associated, Bethlem-London, 1992. Grazia Vailati Schoenburg-Waldenburg, “Testo e immagine: Giovanni di Paolo e la leccetana Comunella dei santi”, in Il codice miniato. Rapporti tra codice, testo e figurazione. Atti del III congresso di Storia della Miniatura, edited by Melania Ceccanti, Maria Cristina Castelli, Olschki, Firenze, 1992, pp. 295-306. 1993 Francesco di Giorgio e il Rinascimento a Siena. 1450-1500, exhibition catalogue (Siena, S. Agostino, 25 April-31 July 1993), edited by Luciano Bellosi, Electa, Milano, 1993. 1996 Alessandra Gianni, “Le imprese, i cavalier, l’arme e gli onori”, in I Libri dei Leoni. La nobiltà di Siena in età medicea (1557-1737), edited by Mario Ascheri, Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo, 1996, pp. 329-361. Enzo Mecacci, “Lo Studio e i suoi codici”, in Lo Studio e i testi... 1996, pp. 17-39. Lo Studio e i testi. Il libro universitario a Siena (secoli XII-XVII), exhibition catalogue (Siena, Biblioteca comunale degli Intronati, 14 September-31 October 1996) edited by Mario Ascheri, Protagon Editori toscani, Siena, 1996. Gennaro Toscano, “Matteo Felice”, in Dizionario biografico degli italiani, 46, Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Roma, 1996, pp. 47-49. Vailati Schoenburg-Waldenburg, “La miniatura nei manoscritti universitari giuridici e filosofici conservati a Siena”, in Lo Studio e i testi... 1996, pp. 79-144. 1997 Bernard Bousmanne, “Item a Guillaume Wyelant aussi enlumineur”. Willem Vrelant: un aspect de l’enluminure dans le Pays-Bas méridionaux sous le mécénat des ducs de Bourgogne Philippe le Bon et Charles le Téméraire, Brepol, Turnhout, 1997. James Hankins, Repertorium Brunianum. A Critical Guide to the Writings of Leonardo Bruni, I. Handlist of Manuscripts, Istituto Storico Italiano, Roma, 1997. Patrizia Turrini, “Ludovico Petroni, diplomatico e umanista senese”, Interpres, 16, 1997, pp. 7-59. 1998 Alessandro Angelini, Gian Lorenzo Bernini e i Chigi tra Roma e Siena, with an essay by Tomaso Montanari, foreward by Paola Barocchi, Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo, 1998. 76 Milvia Bollati, “I Corali”, in La Libreria Piccolomini nel Duomo di Siena, edited by Salvatore Settis, Gabriella Toracca, Panini, Modena, 1998, pp. 321-332. The Illustrated Incunabula Short-Title Catalogue, CD-Rom, edited by Martin Davies, compiled by J. Watson, D. Bird and J. Goldfinch, The British Library-Primary Source Media, London, 19982 (www. bl.uk/catalogues/istc/index.html). 1999 Le due città. Le vedute e le piante di Siena nelle collezioni cittadine (dal XV al XIX secolo), exhibition catalogue (Siena, Magazzini del Sale, 25 marzo-9 maggio 1999), Nuova immagine, Siena, 1999. Siena 1600 circa: dimenticare Firenze. Teofilo Gallaccini (1564-1641) e l’eclisse presunta di una cultura architettonica, exhibition catalogue (Siena, Santa Maria della Scala, 10 December 1999-27 February 2000), edited by Gabriele Morolli, Protagon Editori Toscani, Siena, 1999. Maurits Smeyers, Flemish miniatures fron the 8th to the Mid-16th Century, Brepols, Turnhout, 1999. 2000 Alessandro VII Chigi (1599-1667). Il papa senese di Roma moderna, exhibition catalogue (Siena, Palazzo Pubblico, 23 September 2000-10 January 2001), edited by Alessandro Angelini, Monika Butzek, Bernardina Sani, maschietto&musolino-Protagon Editori Toscani, Siena, 2000. Piergiacomo Petrioli, “Uno sketchbook da Siena”, in Siena 1885. La settimana di un ruskiniano, Biblioteca comunale degli Intronati, Siena [undated but 2000]. 2001 Susan L’Engle, Robert Gibbs, Illuminating the law. Legal manuscripts in Cambridge collections, H. Miller, London, 2001. Marcello Scalzo, “La misura dell’architetto nei disegni di Giuliano da Sangallo: la Villa di Poggio a Caiano”, in Matematica e architettura. Metodi analitici, metodi geometrici e rappresentazione in architettura, Alinea, Firenze, 2001, pp. 83-90. Carolyn C. Wilson, “Giovanni di Paolo”, in Dizionario biografico degli italiani, 56, Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Roma, 2001, pp. 138-146. 2002 Marco Ciampolini, Drawing in Renaissance and Baroque Siena: 16th and 17th Century Drawings from Sienese Collection, exhibition catalogue (Athens, Georgia Museum of Art, 12 October-8 December 2002; Gainesville, Samuel P. Harn Museum of Art, 18 February-20 April 2003; Siena, Palazzo Pubblico, Magazzini del Sale, 7 June-17 July 2003), Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia-Comune di Siena, Athens-Siena 2002. Bénédicte Gady, “Gravure d’interprétation et échanges artistiques. Les estampes françaises d’après les peintres italiens contemporains (1655-1724)”, Studiolo, 1, 2002, pp. 64-104. Inventario dei manoscritti della Biblioteca comunale degli Intronati di Siena, edited by Gino Garosi, I-III, Giuseppe Ciaccheri editore, Siena 2002. La miniatura senese. 1270-1420, edited by Cristina De Benedictis, Skira, Milano, 2002. 2003 Marco Ciampolini, Annotazioni a margine di una mostra. Il disegno a Siena dal Cinquecento all’inizio del Settecento. Breve storia e novità attributive, Protagon Editori Toscani, Siena, 2003. Duccio. Alle origini della pittura senese, exhibition catalogue (Siena, S. Maria della Scala, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, 4 October 2003-11 January 2004), edited by Alessandro Bagnoli, Roberto Bartalini, Luciano Bellosi, Michel Laclotte, Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo, 2003. 77 2004 Gabriele Fattorini, “La passione erudita di Giovanni Antonio Pecci per le ‘cose notabili’ della città di Siena”, in Giovanni Antonio Pecci. Un accademico senese nella società e nella cultura del XVIII secolo (Proceedings of the Conference, Siena, 2 April 2004), edited by Ettore Pellegrini, Accademia senese degli Intronati-Accademia dei Rozzi, Siena 2004, pp. 189-225. 2005 Cristoph L. Frommel, “ ‘Ala maniera e uso delj boni anticuj’: Baldassarre Peruzzi e la sua quarantennale ricerca dell’antico”, in Baldassarre Peruzzi 1481-1536, edited by Cristoph L. Frommel, Arnaldo Bruschi, Howard Burns, Marsilio, Venezia 2005. Giovanna Murano, Opere diffuse per ‘exemplar’ e pecia, Brepols, Turnhout, 2005. 2006 Milvia Bollati, “Gli artisti. Il maestro della Commedia Yates Thompson e Giovanni di Paolo nella Siena del primo Quattrocento”, in La Divina Commedia di Alfonso d’Aragona re di Napoli. Manoscritto Yates Thompson 36 Londra, British Library, 2 voll., edited by Milvia Bollati, Panini, Modena, 2006, I, pp. 63-138. Roberto Barzanti, Alberto Cornice, Ettore Pellegrini, Iconografia di Siena. Rappresentazione della Città dal XIII al XIX secolo, Monte dei Paschi di Siena, Siena, 2006. 2007 Enzo Mecacci, “Codici universitari bolognesi nello Studio di Siena”, Annali delle Università italiane, 11, 2007, pp. 301-310. 2009 Raffaele Argenziano, “L’iconografia del Breviarium fratrum Minorum miniato da Sano di Pietro per il convento di Santa Chiara di Siena”, in Le immagini del francescanesimo. Atti del XXVI convegno internazionale (Assisi, 9-11 ottobre 2008), Fondazione Centro italiano di studi sull’alto Medioevo, Spoleto, 2009, pp. 59-90. Elisa Bruttini, “Ciaccheri, Carli e De Vegni: l’eredità dei manoscritti degli architetti attraverso il Settecento”, in Architetti a Siena. Testimonianze della Biblioteca comunale tra XV e XVIII secolo, exhibition catalogue (Siena, Biblioteca comunale degli Intronati, 19 December 2009-12 April 2010), edited by Daniele Danesi, Milena Pagni, Annalisa Pezzo, Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo, 2009, pp. 15-43. Emanuela Ferretti, “La Sapienza di Siena nei disegni di Giuliano da Sangallo e Francesco di Giorgio Marini”, in Architetti a Siena. Testimonianze... 2009, pp. 71-87. Mauro Mussolin, “Prassi, teoria, antico nell’architettura del Rinascimento. Un percorso per immagini attraverso i documenti della Biblioteca comunale”, in Architetti a Siena. Testimonianze... 2009, pp. 45-69. Annalisa Pezzo, “Mei, Bernardino”, in Dizionario biografico degli italiani, 73, Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Roma, 2009, pp. 200-205. Matthias Quast, “Baldassarre Peruzzi e la visione di una Siena all’antica”, in Architetti a Siena. Testimonianze... 2009, pp. 89-109. Bernardina Sani, “Mecenatismo architettonico a Siena sotto i Medici. Marcello e Ippolito Agostini tra Lorenzo Pomarelli, Damiano Schifardini, Flaminio del Turco”, in Architetti a Siena. Testimonianze... 2009, pp. 111-137. 2010 Marco Ciampolini, Pittori senesi del Seicento, 3 voll., Nuova immagine, Siena, 2010. Le arti a Siena nel primo Rinascimento. Da Jacopo della Quercia a Donatello, exhibition catalogue (Siena, S. Maria della Scala, Opera della Metropolitana, Pinacoteca Nazionale, 26 marzo-11 luglio 2010), edited by Max Seidel, Francesco Caglioti, Laura Cavazzini et alia, Motta, Milano, 2010. 78 Finito di stampare nel mese di giugno dell’anno 2011 per conto della Biblioteca comunale degli Intronati di Siena presso l’Industria grafica Vanzi S.r.l. viale dei Mille, 104 53034 Colle di val d’Elsa (Siena)