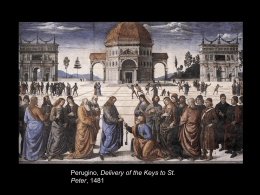

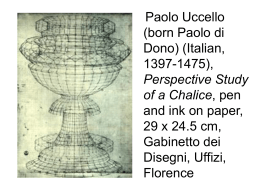

2 11 Raphael Nude Studies, probably for Saint Jerome c. 1504–5 Pen and brown ink, probably retouched with darker brown ink, 238 × 146 mm Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts, 1936 Before his permanent settlement in Rome, Raphael divided himself flexibly between several towns. With a brilliant ability to recognize opportunities, he obtained parallel commissions in Urbino, Città di Castello, Perugia, Siena and Florence. His father’s position as court painter was filled by the Umbrian artist Timoteo Viti (1569–1523),1 and although not formally tied with the ducal court, Raphael sustained connections with his native Urbino. While his residence in the town is solely verified by the acquisition of a house,2 he continued to receive commissions from the court mainly for portraits and small-scale allegorical paintings until 1508.3 Raphael’s first documented altarpiece associates him with Città di Castello, where he executed further works between 1501 and 1504, but he was fulfilling commissions in Perugia from late 1502 until the end of 1505 and in Siena up until 1508, striving to maintain his presence in all these places. While Raphael had probably visited Florence previously,4 from the autumn of 1504 until his arrival in Rome in 1508, he was mostly active in the Tuscan town. These years are frequently referred to as Raphael’s ‘Florentine period’, however, the painter was simultane- ously occupied in Perugia, Siena and Urbino as well.5 Apart from a recommendation of dubious authenticity dating from 1504 and the painter’s letter to his uncle in 1508, no other surviving documents relate to Raphael’s Florentine sojourn.6 This period is primarily illumined by the paintings themselves and by Vasari’s relatively detailed account in the Lives. Although Vasari is indisputably inclined to overestimate the pre-eminence of Tuscan art, it was no exaggeration from him to accentuate the determining influence of Florence on Raphael’s early career. The painter’s enriched artistic concern noticeable in his works from around 1504–5 evidently originated from his Florentine experience. At the turn of the sixteenth century Florence was at the height of its artistic supremacy. The expulsion of the Medici family in 1494 brought about the exceptional painterly undertaking of the period, the decoration of the Sala del Gran Consiglio of the Palazzo della Signoria (Palazzo Vecchio). Leonardo da Vinci (1452−1519) was commissioned to decorate one of the longer walls in the middle of 1503, the pendant of which was entrusted to his younger rival, Michelangelo in the autumn of 1504. The frescoes were to commemorate 28 two decisive military events of the Florentine Republic: one was the victory of the Florentine troops over Pisa in 1364 at Cascina, and the other was their triumph over the Milanese at Anghiari in 1440. Leonardo was engaged in the creation of the Battle of Anghiari, with interruptions, from October 1503 until May 1506, when he returned to Milan and left the unfinished painting behind once and for all. Michelangelo completed the full-scale cartoon of the Battle at Cascina, but never started to paint it [fig. 12].7 Although the undertaking ended in failure, the unexecuted battle scenes perfectly exemplify Leon Battista Alberti’s (1404−1472) concept of dramatic narrative (istoria). In his treatise on painting (Della Pittura) of 1435, Alberti defined istoria as the most ambitious and difficult category of painting,8 in which the biblical, mythological or fictive story is told with variety and decorum.9 In his words, ‘a very great achievement of the painter is the istoria; parts of the istoria are the bodies: part of a body a member: part of a member the surface.’10 Accordingly, the creation of a dynamic composition including figures depicted in the most varied poses became valued higher than the theme itself. Alberti implies that, first and foremost, the proportions among the parts of the human body must be developed and maintained even when the body is shown in motion or 12 Bastiano da Sangallo, after Michelangelo The Battle of Cascina 1542 Oil on panel, 76.5 × 129 cm Norfolk, Holkham Hall, 5 29 foreshortened. He adds that the figures in the scene should move in a manner appropriate to their age, sex, and station, as well as to the emotional content of the event. Finally, Alberti advises that, though an artist should strive to instil his work with variety, he should avoid excess.11 Following these principles, Florentine artists began to focus on the depiction of nude figures in action. Drawing figure and motion studies of workshop apprentices (garzoni) became common practice among Florentine artists from the end of the fifteenth century, and reached Urbino through Perugino’s example.12 Raphael’s preliminary drawings for the angels playing music in the Oddi Coronation attest that he was already applying this method in 13 Raphael Nude Studies, probably for Saint Peter (verso) c. 1504–5 Pen and brown ink 279 × 169 mm London, British Museum, Pp. 1-65 the earliest stage of his career [figs. 7 and 8].13 Although Raphael’s concern with the human nude arose around 1500 through Signorelli’s impact, very few nude studies survive from the period before his 1504 sojourn in Florence.14 In the beginning, Raphael followed Peru gino’s meditative figure type depicted in static poses. His early figure studies demonstrate an approach completely different from the new method of anatomical drawing perfected by Leonardo and Michelangelo at the turn of the century. Before he visited Florence, Raphael rarely used pen; in line with the traditional practice exercised in Perugino’s workshop, he preferred metalpoint or black chalk. His earliest pen drawings were executed in a slightly conservative and descriptive manner, with distinct lines reminiscent of metalpoint and with forms created by accented outlines and regular modelling [fig. 9]. Conversely, late fifteenth-century Florentine drawings are characterized by an increasingly free-flowing handling of the pen. Artists realized the potential of the flexibility of quills and reed pens, which allowed them to draw quickly and directly onto paper, and proved to be perfectly suitable for experimentation. This type of dynamic and expressive pen drawing, dispersed from the workshops of Antonio Pollaiuolo (c. 1432–1498) and Andrea Verrocchio (1435–1488), stimulated the new generation to find various solutions for capturing the human body in action. During the first years of the century Raphael executed a whole series of pen drawings of male figures, most of which represent soldiers or saints. Besides the Saint Peter in London [fig. 13] and the Saint Paul in Oxford [fig. 14], the Budapest drawing is the third in 31 14 Raphael Nude Studies, probably for Saint Paul c. 1504–5 Pen and brown ink 265 × 187 mm Oxford, Ashmolean Museum, 522 the group of saints that has come down to us [fig. 11].15 On the basis of the summarily indicated cardinal’s hat and vestments around the neck and shoulders, the figure is usually identified as Saint Jerome.16 The three drawings, presumably part of a series depicting saints, cannot be connected with a certain commission. The figures’ pose in the London and Budapest drawings suggests a relation with Saints Peter and Paul in Raphael’s Colonna Altarpiece (New York, Metropolitan Museum), painted around 1504–5 for the convent of Sant’ Antonio in Perugia.17 On the other hand, it is more likely that the three saints, akin to his other early Florentine nude studies, were not executed in preparation for a specific commission, but were made as a creative exercise for the pen-and-ink method, which Raphael was experimenting with at this time. The first monographer of Raphael’s drawings, Oskar Fischel, believed that the saints, together with several other Florentine drawings by the painter, belonged originally to a sketchbook. To support his hypothesis, primarily derived from the sketches’ similar theme, Fischel listed the characteristics he found indicative of their origin from a sketchbook: the discoloured corners, the finger prints, the old foliation, and the fact that they were drawn on both sides. He concluded that from the single sheets scattered today in different collections, Raphael’s ‘Large Florentine Sketchbook’ may be reconstructed.18 However, the sixteen sheets Fischel considered are not identical in size, bear no signs of foliation, only thirteen are double-sided, and contrary to his observation, no discolouration or fingerprints are perceivable. Moreover, just the seven drawings preserved today in Oxford bear at least four different watermarks, and two of them have their contours pricked for transfer. All these features contradict the assumption that any of these sheets originally formed part of a sketchbook.19 As successors of the pattern-books that played an essential role in late medieval workshops, sketchbooks came into general use from the mid-fifteenth century. While pattern-books comprised favoured motifs primarily for apprentices to learn their master’s style, artists used sketchbooks to draw anything that caught their attention.20 However, very few bound sketchbooks survived, because draughtsmen understandably preferred single sheets to cumbersome volumes. The original state of sketchbooks is usually difficult to reconstruct; on the one hand they often owe their book-like form to later collectors, while on the other hand many sketchbooks were dismantled during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It is impossible to decide whether Raphael’s figure studies were originally drawn on single sheets or in a bound volume. Most sheets were subsequently trimmed, thus the codicological details that may denote their initial purpose have been lost. In fact, however, pattern-sheets had been in use in Perugino’s workshop, and two fragmentary sketchbooks survived from the painter’s circle.21 Fischel assumed the existence of seven sketchbooks by Raphael from the years before 1512,22 but from the sheets that came down to us only two sketchbooks could be hypothetically reconstructed.23 Even so, sketchbooks and pattern-sheets indisputably played a significant role in Raphael’s early years. In the middle of the fifteenth century Florentine artists treated the human figure primarily as a motif, without sufficient interest in its 32 anatomical representation. Though drawing from life was already a standard practice in the 1470s and 1480s, the majority of surviving studies are mere repetitions of conventional and static poses,24 composed from details of antique and contemporary works. The drawings by Maso Finiguerra (1426–1464) and Antonio Pollaiuolo served as primary models for a rather limited figure repertoire, which Florentine painters integrated in their works with great diversity.25 This eclectic method of figure construction was introduced to Perugino in Verrocchio’s workshop, and transmitted by him to the young Raphael.26 The Budapest Saint Jerome is generally considered among Raphael’s early life studies, but was in fact clearly composed from existing works, mostly drawings and sculptures. The torso on the right appears to have been elaborated from the respective detail in the Oxford 33 15 Antonio Pollaiuolo Male Nude Seen from Three Angles 1470s Pen and wash in brown ink 265 × 360 mm Paris, Musée du Louvre, 1486 16 Leonardo Abdomen and Left Leg of a Nude Man Standing in Profile c. 1506–10 Red chalk on ochre ground 252 × 198 mm London, British Museum, 1886,0609.41 17 Umbrian Artist Nude Study c. 1500–20 Pen and brown ink, 230 × 167 mm Venice, Galleria dell’Accademia, 84 Saint Paul with the addition of the bent left arm [fig. 14]. This torso motif, frequently recurring in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Florentine figure studies, derives from the famous antique statue in the Medici collection, a Roman copy of a famed Hellenistic work, called Red Marsyas for the colour of its marble.27 The statue portraying the skinned and stressed muscular man served for Renaissance artists as a kind of écorché that enabled them to study the anatomical structure of the human body. While during the mid-fifteenth century artists applied antique motifs in an almost unchanged form, towards the end of the century they began to regard them as sources of inspiration. Primary mediators between the Antique and the Renaissance had been the all’antica studies drawn by artists of the previous generation, most of all Antonio Pollaiuolo, whose figures were extensively copied well into the sixteenth century.28 Pollaiuolo was prized as a draughtsman with unique skills of depicting the human body, and his drawings were widely available. His most favoured sheet representing a male nude captured from three views, today in the Louvre, Paris, became one of the most frequently copied pattern-sheets in Florentine workshops [fig. 15].29 Pollaiuolo’s method of representing the figure from several angles indicates a markedly sculptural approach,30 suggesting the study was perhaps drawn after a small wax model with moveable limbs.31 The Paris drawing was employed by both painters and sculptors as an anatomical pattern-sheet, the details of which could be freely adapted to the needs of their own works. Leonardo’s anatomical studies show his indebtedness to Pollaiuolo.32 Between 1490 and 1510 he repeatedly drew the profile view 34 of the leg and abdomen, and turned to the older master’s Paris drawing for inspiration.33 At the same time Leonardo might have been familiar with the Red Marsyas itself, as the statue had been restored in 1475 by his former master, Verrocchio.34 Of Leonardo’s studies of the male torso, the red chalk drawing in London [fig. 16] is closest in time to Raphael’s Oxford drawing. The London sheet has been variously dated some time between Leonardo’s second stay in Florence and his return to Milan, that is between 1503 and 1510, but according to its fragmentary watermark the Milanese years seem more likely.35 As Leonardo’s drawings, with anatomical studies among them, were perhaps accessible to Raphael in Florence, they might have served as intermediate sources to Pollaiuolo’s motifs. The question how the Pollaiuolesque torso became integrated in Raphael’s art is further complicated by its copies in the Umbrian sketchbook known as Libretto Raffaello or Libretto Veneziano [fig. 17].36 The sketchbook dating from the first decades of the sixteenth century originates from the circle of Peru gino, and contains copies after paintings by the master and the young Raphael. It also includes drawings after prints and the Antique, among them the Red Marsyas.37 A sheet from another Umbrian sketchbook dating from the same period portrays the famous statue from three different views.38 The drawings of the two Umbrian sketchbooks were not made after the original works, but seem to be copies after other sheets circulating among workshops.39 The torso in Raphael’s Oxford and Budapest drawings, originating from the Red Marsyas and mediated through Pollaiuolo’s and Leo nardo’s anatomical studies was well-known 18 Michelangelo Nude Study c. 1503–4 Pen and brown ink in two shades 374 × 228 mm London, British Museum, 1887,0502.117 in Umbria primarily via Perugino, indicating that Raphael might have been familiar with the motif even before 1504. However, the style of the Budapest and Oxford figure studies, together with those associated with the ‘Large Florentine Sketchbook’, leave no doubt that they were made during Raphael’s early Florentine years. The Budapest Saint Jerome belongs to Raphael’s earliest Florentine pen drawings, and thus bears the marks of the initial, failed attempts of a draughtsman unfamiliar with the new technique. In his Umbrian pen drawings the main contours were usually first indicated with blind stylus or soft black chalk, whereas the Saint Jerome was executed directly in pen. Taking full advantage of the flexibility of the 35 medium, Raphael endowed the drawing with a look of having been executed at speed. The vigorous, dynamic lines of the Saint Jerome create more organic forms than those in Raphael’s previous drawings. Its style was also influenced by Michelangelo’s pen drawings, most of all his figure studies for the Battle of Cascina [fig. 18]. The Budapest sheet focuses primarily on the main contours, and contrary to the plastically modelled drawings by Michelangelo, Raphael treated the inner forms slightly implausibly with staccato parallel hatching to indicate lighting. Although his handling of the pen gives the impression of spontaneity, the outlines retouched in a darker ink and the accidental inkblot spoil much of its vivacity. In addition to the unintentional defects, the anatomically unresolved details also betray the draughtsman’s inexperience. The qualitative divergence 19 Roman Master Fragment of a Relief Terracotta, 35 × 29 cm Rome, Museo delle Terme, 4359 between the confidently drawn torso and the misconstructed and awkwardly attached left arm leave no doubt that instead of drawing from life, Raphael constructed the figure from various models by other artists. To develop the torso of the Oxford and Budapest sheets into full-figure saints, Raphael was again inspired by existing works. The pose of the Oxford Saint Paul follows Donatello’s (1386/87–1466) famous marble statue of Saint George (Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello) placed in a niche of the façade of Orsanmichele after 1414. Furthermore, the Budapest Saint Jerome holds an almost identical pose to the figure on the left in a fragment of an antique frieze (Rome, Museo delle Terme) [fig. 19].40 Raphael initially strove to perfect the human body portrayed in balanced contrapposto through a limited figure repertoire, therefore variations of the Budapest and Oxford saints may be found in several of his contemporaneous pen drawings. The central figure of his study for a group of warriors [fig. 20] also recalls Donatello’s Saint George, while the male nude to the right closely corresponds with the aforementioned antique relief.41 Donatello’s Saint George embodied the Renaissance prototype of the powerful, heroic figure and was frequently repeated from the moment of its installation. Perugino must have been particularly fond of the statue and included its pose in several of his works, thus the fifteenth-century model was transmitted to Raphael even before his arrival in Florence.42 The fact that the central figure of Raphael’s group study in Oxford is closer to Perugino’s drawing at Windsor [fig. 21] than to Donatello’s statue suggests that Raphael worked after a drawing from the Perugino 37 don [fig. 22].46 If Raphael adopted this figure directly from the antique frieze he must have seen the original relief in Rome.47 The figure on the right on the London sheet seems to add further support to the theory of a trip to Rome before 1508, because its possible model, the Apollo Sauroktonos (Naples, Museo Archeologico) was housed in the Sassi Collection in Rome at the beginning of the sixteenth century.48 As a large number of Raphael’s figure studies from the period between 1504 and 1508 are closely related to antique Roman works, the painter’s presence in the town seems highly probable.49 However, replicas of Roman antiquities were widely accessible in Florence from the 1460s, and copies after the 20 Raphael A Group of Warriors c. 1504–5 Pen and brown ink, 271 × 216 mm Oxford, Ashmoelan Museum, 523 21 Perugino Man in Armour c. 1490–93 Metalpoint, pen and ink, heightened with white, on blue ground, 250× 189 mm Windsor, Royal Collection, RL 12801 22 Raphael A Group of Nude Men c. 1504–5 Pen and brown ink, 243 × 148 mm London, British Musem, 1895,0915.628 workshop instead of the original marble itself.43 Although executing figure studies after statues was a common practice throughout Italy, and therefore also in Giovanni Santi’s and Perugino’s workshops, when they were to record existing motifs, painters preferred pattern-sheets to three-dimensional works. It appears that Raphael mastered the newly acquainted method of pen by drawing from well-known models, and extended his figure repertoire only after he had gained some confidence in the new artistic formulas and ideals of great masters.44 Raphael’s drawing inspired by the antique relief raises the possibility that he may have visited Rome prior to his Florentine sojourn in 1504.45 The pose of the Budapest Saint Jerome was developed from the right hand figure of the Oxford drawing [fig. 20] and appears in reverse on another sheet in Lon- 38 Antique drawn by Perugino and Pintoricchio also played an important role in their mediation in Umbria as well. Considering that only a small number of these possible intermediate drawings survive, in some cases Raphael’s direct sources are impossible to define. As he initially borrowed motifs from various artworks in his figure studies, it seems more plausible that he worked from easily available drawn copies after the Antique, rather than from the original works. His early Florentine figure studies mark the shift from Umbrian late medieval pattern-book tradition to the new concept of the human figure introduced by Leonardo and Michelangelo. The Budapest sheet suffered several later interventions. It was not only trimmed, but the image taken in backlight has revealed that the sheet was also split [fig.23].50 The procedure of dividing a paper in two halves, thus obtaining two separate drawings from a double-sided sheet was a common practice among art dealers and collectors from the eighteenth century on.51 As a result of this process, the Budapest sheet became extremely thin, and its fragility provoked the loss of a major part at the left edge and the lower right corner. When it was adhered to a secondary sheet, attempts were made to repair the damage and reattach the small specks of paper. The unsuccessful repair of the tears and losses indicates it was executed by a different person from the one who split the sheet, which demands the skills of a professional.52 The date of these interventions is uncertain. Before the Saint Jerome entered the Esterházy Collection, it had been reproduced by the lesser-known Florentine painter and etcher Sante Pacini (1735–1790).53 Pacini’s etching in reverse is a precise but not mechanical copy after 39 23 Fig. 11 in transmitted light Raphael’s drawing; the printmaker accentuated certain lines while omitting others, as well as the accidental inkblot. It is impossible to judge whether Pacini deliberately eliminated the damage, or if the damage was sustained after his etching was created. As there is no trace of the drawing’s provenance before it entered the Esterházy Collection, Pacini’s print is the earliest document concerning its origin.54 Although Pacini reproduced several of Raphael’s drawings, apart from his etching after a lost Raphael sheet once owned by the German painter and writer, Anton Raphael Mengs (1728–1779), their provenance is unknown.54 Therefore we may only assume that the Budapest Saint Jerome remained in Florence until the end of the eighteenth century.55 40 1 For Timoteo Viti, see Ferriani 1983 and Cleri 2009. 2 Shearman 2003, pp. 104–6. 3 For Raphael’s Umbrian works, see Urbino 2009. 4 For Raphael’s presumed stay in Florence between 1493 and 1494, see Becherucci 1968, pp. 12–15. 5 For Raphael’s Sienese commissions, see Henry 2004. 6 For the recommendation by Giovanna Feltria to Piero Soderini, the authenticity of which has been debated, see Shearman 2003, pp. 1457–62; for Raphael’s letter to Simone Ciarla dated 21 April, 1508, see ibid., pp. 112–13. 7 For the commission and the cartoons, see Meyer zur Capellen 1996, pp. 86–97. 8 For Alberti’s Della Pittura, see Alberti (Sinsigalli) 2006. For the influence of Alberti’s istoria on Raphael’s art, see Becherucci 1969, p. 25; Plemmons 1978, pp. 187–224; Rosenberg 1986; Ferino-Pagden 1992. 9 For Alberti’s istoria, see Alberti (Sinsigalli) 2006, p. 369, note 228. 10 Alberti (Sinsigalli) 2006, II, 33. 11 Ibid., II, 40. 12 Ames-Lewis 1981, pp. 91–103; Forlani Tempesti 1994. 13 Ames-Lewis 1986, pp. 24–25 and Joannides 1983, nos. 40, 41, 43r, 44 and 47r. 14 The impact of Signorelli’s works on Raphael’s art is most manifest between 1500 and 1503, while his frescoes in Orvieto influenced Raphael during his entire career, see Gilbert 1986 and Henry 2009. For a drawing by Raphael on the verso of a sheet from Signorelli’s Orvieto workshop, see Henry 1993 and 2012, pp. 200–1, cf. Bambach 1992 and 1999, p. 475, note 33. 15 Joannides 1983, nos. 85r and 87r. The warrior with a spear on the back of the Oxford sheet is usually identified with Saint George, see ibid., no. 87v. 16 Passavant 1860, vol. 2, pp. 417–18, no. 242. 17 Meyer zur Capellen 2001, no. 17; more extensively Wolk-Simon 2006, esp. nos. 14 and 15. 18 For Raphael’s ‘Large Florentine Sketchbook or Sketchbooks’ (Großes Florentiner Skizzenbuch), see Fischel, vol. 2, pp. 88–89; Fischel 1939, p. 182, note 3. Fischel reproduced 16 sheets on 22 plates, see Fischel vol. 2, nos. 81–102 (Joannides 1983, nos. 85r–v, 86, 87r–v, 88r, 89, 91r–v, 93r, 94r–v, 108r, 114r, 135r, 146r–v, 147, 157v, 158r, 191r–v). 19 For the criticism of Fischel’s hypothesis, see Parker 1956, p. 270 (mistakenly including Fischel vol. 2, no. 103 in his list); Parker 1939–40, p. 38; Pouncey and Gere 1962, p. 13; Gere and Turner 1983, p. 59. 20 For pattern-books and sketchbooks in general, see Ames-Lewis 1981, esp. pp. 63–89; Scheller 1995 and Elen 1995. 21 For the two sketchbooks, see Schmitt 1970, pp. 107–22; Ferino-Pagden 1982, no. 83; Ferino-Pagden 1984, pp. 13–31; Elen 1995, nos. 38 and 43. 22 Fischel 1939, esp. p. 182. 23 Elen 1995, nos. 45 and 47. 24 Ragghianti and Dalli Regoli 1975. 25 Whitaker 1998 and 2012. 26 Kwakkelstein 2004. 27 For the two Marsyas statues owned by the Medicis, see Bober and Rubinstein 1986, p. 72. For the dilemma whether the Red and the White Marsyas today in the Uffizi are identical with the statues mentioned by Vasari, see Osano 1996, pp. 98–103 and Burroughs 2001, esp. p. 44, notes 20 and 24. For the Marsyas statues of the Uffizi, see Mansuelli 1958, nos. 56 and 57. 28 For the antique models used by Antonio Pollaiuolo, see Fusco 1979. 29 For the drawing, see Wright 2005, pp. 158–62; for the copies of the drawing, see Fusco 1982, pp. 186, esp. pp. 192–94. 30 Ames-Lewis 1981, pp. 104–10. 31 For the question, see Nathan 1995, pp. 73–81. 32 For Antonio Pollaiuolo’s influence on Leonardo’s anatomical drawings and for the supposition that following his predecessor, Leonardo perhaps also executed sculptural wax écorché models, see Kwakkelstein 2004. 33 Windsor, Royal Collection, 12625 and 12632; London, British Museum, 1886,0609.41; Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, 1355; for the drawings, see Clark and Pedretti 1968, under nos. 12625 and 12632. 34 Vasari (ed. Milanesi), vol. 3, pp. 366–67; vol. 4, p. 10; Caglioti 1993–94. The red nude included in the sculptor’s inventory of 1496 is usually identified with the Red Marsyas, see Rubin and Wright 1999, pp. 39 and 43. 35 For the red chalk drawing in London, see most recently, Hugo Chapman in London and Florence 2010–11, no. 57. 36 Ferino-Pagden 1982, nos. 83/14r, 33v, 34r, 35r–v, 40r. For the sheets separate today but originally forming a sketchbook, see ibid., no. 83; Ferino-Pagden 1984, pp. 13–31; Elen 1995, no. 43. 37 Ferino-Pagden 1982, no. 83/6v. 38 Schmitt 1970, p. 116 and fig. 24. For the fragmentary sketchbook, see also Elen 1995, no. 38. For the relation of the Oxford and Budapest drawings with the Umbria sketchbook including copies of the Red Marsyas, see Plemmons 1978, pp. 123–27. Plemmons’s supposition that the direct source for Raphael’s torso was probably one of the drawn copies after the Red Marsyas is contradicted by the fact that the Hellenistic hanging Marsyas, as opposed to the torso of the Oxford drawing, stands on his tiptoes. On the other hand, Raphael must have been in acquaintance with the statue or one of its replicas, as he quoted it in the Apollo and Marsyas fresco on the ceiling of the Stanza della Segnatura, see Dussler 1971, p. 70. 39 Elen 1995, p. 263, notes 8 and 9. 40 Fischel vol. 2, p. 113, under no. 87; Becatti 1969, p. 504, figs. 7 and 8; Rohden and Winnefeld 1911, no. XLVIII. 41 Joannides 1983, no. 88r; Gere and Turner 1983, no. 46; Hugo Chapman in Chapman, Henry, and Plazzotta 2004, no. 47. 42 Donatello’s Saint George was repeatedly quoted by Perugino: for the figure of Saint Michael in his altarpiece of 1496 for the Certosa di Pavia (London, National Gallery, see Scarpellini 1984, no. 104), for Julius Sicinius in the wall-painting in Perugia, Collegio del Cambio (ibid., no. 94), and for Saint Michael in his Florentine Ascension altarpiece (Florence, Galleria dell’Accademia; ibid., no. 112), see Hiller von Gaertrigen 2004, esp. pp. 345–47. 43 Windsor, Royal Collection, RL 12801, see Clayton 1999–2001, no. 5; Carol Plazzotta in Chapman, Henry, and Plazzotta 2004, no. 3. 44 Ames-Lewis 1986, pp. 39–50; Kwakkelstein 2004 and 2007. 45 For the possibility that Raphael visited Rome around 1503, and in 1506 or 1507 as well, see Shearman 1977, p. 131. 46 Joannides 1983, no. 89; Gere and Turner 1983, no. 48; for the provenance of the drawing, see Gibson-Wood 2003, p. 168, note 42. 47 Becatti 1969, p. 504. 41 48 For the antique statue and its Renaissance replicas, see http://census.bbaw.de/easydb/censusID=159347 (May 25, 2013). The statue appears in several drawings by Raphael dated after 1508, see Joannides 1983, nos. 264r, 186v, 202r and 265r. 49 For further examples and a detailed discussion of the issue, see Kwakkelstein 2004 and 2007. It is notable, however, that the right hand figure on the London sheet is closely related with Michelangelo’s drawing made in Florence around 1501–3 (Hartt 1971, no. 6), but it is difficult to judge whether Michelangelo’s source for this was the antique marble of the Three Graces in the Piccolomini Library, Siena (ibid.) or the antique Apollo torso of the Sassi Collection (Ekserdjian 1993). 50 The Budapest drawing was executed on the wire side of the split paper, where the chain lines are clearly visible and a faint and fragmentary watermark also appears [see Appendix II]. The poor condition and extremely thin paper of a Raphael drawing in the British Museum, London (1895,0915.628; fig. 22), executed in the same period implies its paper had probably been also split. Their almost identical size suggests that the Budapest and London drawings might have orig- inally constituted a single sheet. Our hypothesis is supported not only by their similarity in style, but also that unusually among Raphael’s early figure studies both drawings are single-sided. This would not be the only instance of a Florentine drawing by Raphael being split: a double-sided drawing in the British Museum, London (Pp, 1.75, see Joannides 1983, no. 187) was assembled from two split and seriously damaged sheets. As the London sheet, here presumed to be the counterpart of the Budapest drawing, is attached to a second ary support, we had no opportunity to examine its paper in translucent light. To our inquiry, however, Hugo Chapman confirmed that the paper of the London drawing is indeed extremely thin. 51 For the technique of paper splitting, see Walsh 2000 and Smentek 2008. 52 The whole paper is of the same thickness save for the creased, torn parts where it is somewhat thicker, which indicates that the damage was not caused during the splitting process. 53 Höper 2001, no. A108. Fabia Borroni Salvadori suggests that Pacini included his etchings after old master drawings, including those by Raphael, in his series of prints titled Scelta di disegni originali di eccellenti autori incisi in rame da Santi Pacini Fiorentino [...], published in 1789. In this series the description of print no. 6B (Due schizzi di nudi virili, di cui uno a tutta figura) may correspond with the Budapest drawing; for the quotation see Borroni Salvadori 1985, p. 52, note 45. However, we did not succeed in finding the mentioned album in any collection. Giorgio Marini kindly informed us that the etching reproducing the Budapest drawing is the penultimate page (2923) of a series preserved in the Uffizi, Florence (2875–2924). 54 The inventory of prints and drawings of the Esterházy Collection, preserved in the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, is a copy of 1834 from the original inventory compiled in 1819 and does not include any information on the provenance of the drawing, see Gonda 1999, pp. 204, 219, note 48. 55 Cordellier and Py 1992a, p. 517. 56 Although in his testament of 1765 Ignazio Enrico Hugford appointed Pacini as heir to his works remaining in the Florentine workshop, upon his death his drawings finally entered the Uffizi (Serafini 2004), thus the Budapest drawing could not have been among those bequeathed by Hugford. Alberti (Sinisgalli) 2006 Rocco Sinisgalli, Il nuovo De pictura di Leon Battista Alberti/The New De Pictura of Leon Battista Alberti, Rome 2006 Allison 1974 Ann H. Allison, ‘Antique Sources of Leonardo’s Leda’, Art Bulletin 56 (1974), pp. 375–84 Ambers, Higgitt, and Saunders 2010 Janet Ambers, Catherine Higgitt, and David Saunders (eds.), Italian Renaissance Drawings: Technical Examination and Analysis, London 2010 Ames-Lewis 1981 Francis Ames-Lewis, Drawing in Early Renaissance Italy, New Haven and London 1981 Ames-Lewis 1986 Francis Ames-Lewis, The Draftsman Raphael, New Haven and London 1986 Ames-Lewis 1999 Francis Ames-Lewis, ‘Raphael and his Circle’, Apollo 150 (1999), pp. 53–55 Angelini 1986 Aldo Angelini, La Loggia della Galatea alla Villa Farnesina a Roma: L’ incontro delle scuole Toscana, Umbra e Romana (1511–1514), in Tecnica e stile. Esempi di pittura murale del Rinascimento italiano, eds. Eve Borsook and Fiorella Superbi Gioffredi, Florence 1986, pp. 95–110 Athens 2003–4 In the Light of Apollo: Italian Renaissance and Greece, ed. Mina Gregori, exhibition catalogue, 2 vols., Athens, Alexandros Soutzos Museum 2003–4 Bacchi et al. 1988 Andrea Bacchi et al., La pittura del Cinquecento a Roma e nel Lazio I: Da Giulio II al Sacco di Roma, in Giuliano Briganti (ed.), La pittura in Italia: Il Cinquecento, Milan 1988 Balniel and Clark 1931 Lord Balniel and Kenneth Clark (eds.), A Commemorative Catalogue of the Exhibition of Italian Art Held in the Galleries of the Royal Academy, Burlington House, London, exhibition catalogue, London 1931 Bambach 1992 Carmen C. Bambach, ‘A Substitute Cartoon for Raphael’s Disputa’, Master Drawings 30 (1992), pp. 9–30 Bambach 1999 Carmen C. Bambach, Drawing and Painting in the Italian Renaissance Workshop: Theory and Practice, 1300–1600, Cambridge 1999 Bambach 2003 Carmen C. Bambach (ed.), Leonardo da Vinci: Master Draftsman, exhibition catalogue, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art 2003 Barocchi, Ristori, and Poggi 1965–83 Paola Barocchi, Renzo Ristori, and Giovanni Poggi, Il Carteggio di Michelangelo, 5 vols., Florence 1965–83 Bartalini 1996 Roberto Bartalini, Le occasioni del Sodoma: Dalla Milano di Leonardo alla Roma di Raffaello, Rome 1996 Bartalini 2001 Roberto Bartalini, ‘Sodoma, the Chigi and the Vatican Stanze’, The Burlington Magazine 143 (2001), pp. 544–53 Bartsch Adam Bartsch, Le peintre-graveur, 21 vols., Vienna 1803–21 Battistelli 1974 Franco Battistelli, ‘Notizie e documenti sull’ attività del Perugino a Fano’, Antichità viva 13 (1974), pp. 65–68 Becatti 1969 Giovanni Becatti, Raphael and Antiquity, in Salmi 1969, pp. 491–568 Becherucci 1968 Luisa Becherucci, Raffaello e la pittura, in Salmi 1968 Becherucci 1969 Luisa Becherucci, Raphael and Painting, in Salmi 1969, pp. 9–197 Beck 1986 James Beck (ed.): Raphael before Rome, in Studies in the History of Art 17, Washington (DC) 1986 Bellori 1695 Giovanni Pietro Bellori, Descrizione delle quattro immagini dipinte da Raffaelle d’Urbino nella Camera della Segnatura nel Palazzo Vaticano (Rome 1695), in Descrizione delle immagini dipinte da Raffaelle d’Urbino nel Vaticano e di quelle della Farnesina, ed. Melchior Missirini, Rome 1821 140 Belluzzi 1988 Amadeo Belluzzi, ‘Giulio di Raffaello da Urbino’, Quaderni di Palazzo Tè 8 (1988), pp. 9–20 Berenson 1897 Bernard Berenson, The Central Italian Painters of the Renaissance, New York and London 1897 Berenson 1932 Bernard Berenson, Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, Oxford 1932 Berenson 1936 Bernard Berenson, Pitture italiane del Rinascimento, Milan 1936 Berenson 1957–68 Bernard Berenson, Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Central Italian and North Italian Schools, 3 vols., London 1957–68 Bianchi 1968 Lidia Bianchi, La fortuna di Raffaello nell’incisione, in Becherucci 1968, pp. 647–89 Birke and Kertész 1992–97 Veronika Birke and Janine Kertész, Die italienischen Zeichnungen der Albertina, 4 vols., Vienna 1992–97 Blunt 1972–73 Anthony Blunt, Drawings by Michelangelo, Raphael and Leonardo, exhibition catalogue, Windsor, Royal Collection 1972–73 Bober 1957 Phyllis Pray Bober, Drawings after the Antique by Amico Aspertini: Sketchbooks in the British Museum, London 1957 Bober and Rubinstein 1986 Phyllis Pray Bober and Ruth Rubinstein, Renaissance Artists and Antique Sculpture: A Handbook of Sources, London 1986 Bologna 1988 Bologna e l’Umanesimo 1490–1510, eds. Marzia Faietti and Konrad Oberhuber, exhibition catalogue, Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale 1988 Bomford 2002 David Bomford (ed.), Art in the Making: Underdrawings in Renaissance Paintings, London 2002 Bonn 1998–99 Hochrenaissance im Vatikan: Kunst und Kultur im Rom der Päpste I. 1503–1534, exhibition catalogue, Bonn, Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland 1998–99 Borea 1989–90 Evelina Borea, ‘Vasari e le stampe’, Prospettiva 57–60 (1989–90), pp. 18–38 Borroni Salvadori 1985 Fabia Borroni Salvadori, ‘Per un approccio a Santi Pacini, incisore’, Antichità viva 24, nos. 5–6 (1985), pp. 50–57 Braun 1815 Georg Christian Braun, Raphael’s Leben und Werke, Wiesbaden 1815 Brown 1992 David Alan Brown, Raphael, Leonardo, and Perugino: Fame and Fortune in Florence, in Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael in Renaissance Florence from 1500 to 1508, ed. Serafina Hager, Washington (DC) 1992, pp. 29–53 Brown and Oberhuber 1978 David Alan Brown and Konrad Oberhuber, Monna Vanna and Fornarina: Leonardo and Raphael in Rome, in Essays Presented to Myron P. Gilmore, eds. Sergio Bertelli and Gloria Ramakus, Firenze 1978, vol. 2, pp. 25–86 Budapest 1876 Catalog der Landes-Gemälde-Gallerie in AcademieGebäude, Budapest 1876 Budapest 1878 Az Országos Képtár képeinek jegyzéke az Akadémia épületében, Budapest 1878 Budapest 1897 Az Országos Képtár műtárgyainak leíró lajstroma hivatkozással a korábbi katalógusokra, Budapest 1897 Budapest 2008 The Splendour of the Medici, eds. Monica Bietti and Annamaria Giusti, exhibition catalogue, Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts 2008 Budapest 2009 Botticelli to Titian: Two Centuries of Italian Masterpieces, eds. Dóra Sallay, Vilmos Tátrai, and Axel Vécsey, exhibition catalogue, Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts 2009 Burroughs 2001 Charles Burroughs, ‘Monuments of Marsyas: Flayed Wall and Echoing Space in the New Sacristy, Florence’, Artibus et Historiae 44 (2001), pp. 31–49 Bury 1985 Michael Bury, ‘The Taste for Prints in Italy to c. 1600’, Print Quarterly 2 (1985), pp. 12–26 Bury 2001 Michael Bury, The Print in Italy 1550–1620, exhibition catalogue, London, British Museum 2001 Butler 2004 Kim E. Butler, ‘Riconsiderando il primo Raffaello’, Accademia Raffaello: Atti e studi 1 (2006), pp. 63–87 Butler 2009 Kim E. Butler, ‘Giovanni Santi, Raphael, and Quattrocento Sculpture’, Artibus et Historiae 30 (2009), pp. 15–39 Büttner 2001 Frank Büttner, Thesen zur Bedeutung der Druckgraphik in der italienischen Renaissance, in Druckgraphik: Funktion und Form, Berlin 2001, pp. 9–15 Caglioti 1993–94 Francesco Caglioti, ‘Due restauratori per le antichità dei primi Medici. Mino da Fiesole, Andrea del Verrocchio e il Marsia rosso degli Uffizi’, Prospettiva 72 (1993), pp. 17–42; 73–74 (1994), pp. 74–96 Caglioti 2000 Francesco Caglioti, Donatello e i Medici: Storia del David e della Giuditta, Florence 2000 Cambridge 1974 Rome and Venice: Prints of the High Renaissance, ed. Konrad Oberhuber, exhibition catalogue, Cambridge (MA), Fogg Art Museum 1974 Camesasca 1956 Ettore Camesasca, Tutta la pittura di Raffaello: I Quadri, Milan 1956 Canuti 1931 Fiorenzo Canuti, Il Perugino, 2 vols., Siena 1931 Carpi 2009 Ugo da Carpi: L’ opera incisa. Xilografie e chiaroscuri da Tiziano, Raffaello e Parmigianino, ed. Manuela Rossi, exhibition catalogue, Carpi, Palazzo dei Pio 2009 141 Castagnoli 1968 Ferdinando Castagnoli, Raffaello e le antichità di Roma, in Salmi 1968 Cecchelli 1942 Carlo Cecchelli, ‘Di una ignota fonte letteraria della Galatea di Raffaello’, Rivista di studi e di vita romana 20 (1942), pp. 246–48 Chapman, Henry, and Plazzotta 2004 Hugo Chapman, Tom Henry, and Carol Plazzotta, Raphael: From Urbino to Rome, exhibition catalogue, London, National Gallery 2004 Clark 1952 Kenneth Clark, Leonardo da Vinci: An Account of His Development as an Artist, 2nd ed., Cambridge 1952 Clark and Pedretti 1968 Kenneth Clark and Carlo Pedretti, The Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen at Windsor Castle, 2nd ed. rev., 3 vols., New York 1968 Clayton 1999–2001 Martin Clayton, Raphael and his Circle: Drawings from Windsor Castle, exhibition catalogue, London, The Queen’s Gallery, Washington (DC), The National Gallery of Art, Toronto, The Art Gallery of Ontario, and Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum 1999–2001 Clément 1861 Charles Clément, Michel-Ange, Léonard de Vinci, Raphaël: Avec une étude sur l’art en Italie avant le XVIe siècle et des catalogues raisonnès historiques et bibliographiques, Paris 1861 Cooper 2004 Donal Cooper, ‘New Documents for Raphael and his Patrons in Perugia’, The Burlington Magazine 146 (2004), pp. 742–44 Cordellier and Py 1992a Dominique Cordellier and Bernadette Py, Inventaire Général des Dessins Italiens V: Raphaël, son Atelier, ses Copistes, Paris 1992 Cordellier and Py 1992b Dominique Cordellier and Bernadette Py, Raffaello e i Suoi: Disegni di Raffaello e della Sua Cerchia, exhibition catalogue, Rome, Villa Medici 1992 Corini 1993 Guido Corini (ed.), Raffaello nell’appartamento di Giulio II e Leone X, Milan 1993 Costamagna 2005 Philippe Costamagna, ‘The Formation of Florentine Draftsmanship: Life Studies from Leonardo and Michelangelo to Pontormo and Salviati’, Master Drawings 43 (2005), pp. 274–91 Cox-Rearick 1999 Janet Cox-Rearick (ed.), Giulio Romano: Master Designer, exhibition catalogue, New York, The Berta and Karl Leubsdorf Art Gallery and Hunter College of the City University of New York 1999 Crowe and Cavalcaselle 1883–85 Joseph Archer Crowe and Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle, Raphael: His Life and Works, 2 vols., London, 1883–85 Cleri 2009 Bonita Cleri, Timoteo Viti, in Urbino 2009, pp. 74–77 Cust 1906 Robert Henry Hobart Cust, Giovanni Antonio Bazzi Hitherto Usually Styled ‘Sodoma’: The Man and the Painter 1477–1549, London 1906 Coonin 1999 Arnold Victor Coonin, ‘New Documents Concerning Perugino’s Workshop in Florence’, The Burlington Magazine 141 (1999), pp. 100–4 Dacos 1969 Nicole Dacos, La découverte de la Domus Aurea et la formation des grotesques à la Renaissance, London and Leiden 1969 Coonin 2003 Arnold Victor Coonin, ‘The Interaction of Painting and Sculpture in the Art of Perugino’, Artibus et Historiae 47 (2003), pp. 103–20 Dacos 1977 Nicole Dacos, Le Logge di Raffaello: maestro e bottega di fronte all’antico, Rome 1977 Cooper 2001 Donal Cooper, ‘Raphael’s Altar-Pieces in S. Francesco al Prato, Perugia: Patronage, Settings and Function’, The Burlington Magazine 143 (2001), pp. 554–61 Dacos 1989 Nicole Dacos, Le rôle des plaquettes dans la diffusion des gemmes antiques: Le cas de la collection Médicis, in Italian Plaquettes, ed. Alison Luchs, Washington (DC) 1989, pp. 71–91 Dacos 2004 Nicole Dacos, De Pinturicchio à Michelangelo di Pietro da Luca: Les premières grotesques romaines, in Roma nella svolta tra Quattro e Cinquecento: Atti del convegno internazionale di studi, Rome 1996, Rome 2004, pp. 325–40 Dalli Regoli, Nanni, and Natali 2001 Gigetta Dalli Regoli, Romano Nanni, and Antonio Natali, Leonardo e il mito di Leda: Modelli, memorie e metamorfosi di un’invenzione, exhibition catalogue, Vinci, Palazzina Uzielli del Museo Leonardiano 2001 Damisch 1992 Hubert Damisch, Le jugement de Pâris, Paris 1992 Davidson 1987 Bernice Davidson, ‘A Study for the Farnesina Toilet of Psyche’, The Burlington Magazine 129 (1987), pp. 510–13 De Vecchi 1986 Pierluigi de Vecchi, The Coronation of the Virgin in the Vatican Pinacoteca and Raphael’s Activity between 1502 and 1504, in Beck 1986, pp. 73–82 De Vecchi 1995 Pierluigi de Vecchi, Raffaello: La mimesi, l’armonia e l’invenzione, Florence 1995 De Vecchi 2002 Pierluigi de Vecchi, Raphaël, Paris 2002 Delaborde 1888 Henri Delaborde, Marc-Antoine Raimondi: Étude historique et critique suivie d’un catalogue raisonné des œuvres du maître, Paris 1888 Delogu 1936 Giuseppe Delogu, ‘Arte italiana in Ungheria’, Emporium 83 (1936), pp. 171–86 Donati 1963 Lamberto Donati, Due note d’iconografia raffaellesca, in Biblioteca degli eruditi e dei bibliofili 85, Florence 1963, pp. 10–24 Dorez 1896 Léon Dorez, ‘La bibliothèque privée du Pape Jules II’, Revue des bibliothèques 6 (1896) Dryhurst 1905 Alfred Robert Dryhurst, Raphael, London 1905 142 Du Bois-Reymond 1978 Irena du Bois-Reymond, Die römischen Antikenstiche Marcantonio Raimondis, Munich 1978 Falcioni 2009 Anna Falcioni, Documenti urbinati sulla famiglia Santi, in Urbino 2009, pp. 268–84 Dunkerton and Penny 1993 Jill Dunkerton and Nicholas Penny, ‘The InfraRed Examination of Raphael’s Garvagh Madonna’, National Gallery Technical Bulletin 14 (1993), pp. 6–21 Fenyő 1963 Iván Fenyő, Középitáliai rajzok: Bologna, Firenze, Róma, exhibition catalogue, Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts 1963 Dunkerton and Roy 1996 Jill Dunkerton and Ashok Roy, ‘The Materials of a Group of Late-Fifteenth-Century Florentine Panel Paintings’, National Gallery Technical Bulletin 17 (1996), pp. 21–31 Dussler 1966 Luitpold Dussler, Raffael: Kritisches Verzeichnis der Gemälde, Wandbilder und Bildteppiche, Munich 1966 Fenyő 1967 Iván Fenyő, Meisterzeichnungen aus dem Museum der Schönen Künste in Budapest, exhibition catalogue, Vienna, Albertina 1967 Ferino-Pagden 1979 Sylvia Ferino-Pagden, ‘A Master-Painter and his Pupils: Pietro Perugino and his Umbrian Workshop’, The Oxford Art Journal 3 (1979), pp. 9–14 Dussler 1971 Luitpold Dussler, Raphael: A Critical Catalogue of His Pictures, Wall-Paintings and Tapestries, London 1971 Ferino-Pagden 1982 Sylvia Ferino-Pagden, Disegni umbri del Rinascimento da Perugino a Raffaello, exhibition catalogue, Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi 1982 Edinburgh 1994 Raphael: The Pursuit of Perfection, ed. Timothy Clifford, exhibition catalogue, Edinburgh, National Galleries of Scotland 1994 Ferino-Pagden 1983 Sylvia Ferino-Pagden, ‘Pintoricchio, Perugino or the Young Raphael? A Problem of Connoisseurship’, The Burlington Magazine 125 (1983), pp. 87–88 Egger 1905–6 Hermann Egger (ed.): Codex Escurialensis: Ein Skizzenbuch aus der Werkstatt Domenico Ghirlandaios, Vienna 1905–6 Ferino-Pagden 1984 Sylvia Ferino-Pagden, Disegni umbri. Gallerie dell’Accademia di Venezia, Milan 1984 Ekserdjian 1993 David Ekserdjian, ‘Parmigianino and Michelangelo’, Master Drawings 31 (1993), pp. 390–94 Elen 1995 Albert J. Elen, Italian Late-Medieval and Renaissance Drawing-Books: From Giovannino de’Grassi to Palma Giovane: A Codicological Approach, Leiden 1995 Emison 1984 Patricia Emison, ‘Marcantonio’s Massacre of the Innocents’, Print Quarterly 1 (1984), pp. 257–67 Epé 1990 Elisabeth Epé, Die Gemäldesammlungen des Ferdinando de’ Medici, Erbprinz von Toskana (1663–1713), Marburg 1990 Evans and Browne 2010 Mark Evans and Clare Browne, Raphael: Cartoons and Tapestries for the Sistine Chapel, London 2010 Ferino-Pagden 1985 Sylvia Ferino-Pagden, ‘Raffaello giovane e gli artisti umbri contemporanei’, Arte cristiana 73 (1985), pp. 263–78 Ferino-Pagden 1986a Sylvia Ferino-Pagden, Iconographic Demands and Artistic Achievements: The Genesis of Three Works by Raphael, in Rome 1986, pp. 13–27 Ferino-Pagden 1986b Sylvia Ferino-Pagden, The Early Raphael and His Umbrian Contemporaries, in Beck 1986, pp. 93–107 Ferino-Pagden 1987 Sylvia Ferino-Pagden, Invenzioni raffaellesche adombrate nel Libretto di Venezia: La Strage degli Innocenti e la Lapidazione di Santo Stefano a Genova, in Sambucco and Strocchi 1987, pp. 63–72 Ferino-Pagden 1990 Sylvia Ferino-Pagden, ‘Raphael’s Heliodorus Vault and Michelangelo’s Ceiling: An Old Controversy and a New Drawing’, The Burlington Magazine 132 (1990), pp. 201–3 Ferino-Pagden 1992 Sylvia Ferino-Pagden, Raphael’s Invention of Storie in His Florentine Drawings, in Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael in Renaissance Florence from 1500 to 1508, ed. Serafina Hager, Washington (DC) 1992, pp. 89–120 Ferino-Pagden and Zancan 1989 Sylvia Ferino-Pagden and Maria Antonietta Zancan, Raffaello. Catalogo completo dei dipinti, Florence 1989 Fermor and Derbyshire 1998 Sharon Fermor and Alan Derbyshire, ‘The Raphael Tapestry Cartoons Re-Examined’, The Burlington Magazine 140 (1998), pp. 236–50 Ferriani 1983 Daniela Ferriani, Timoteo Viti, in Urbino 1983, pp. 279–281 Finocchi Ghersi 2010 Lorenzo Finocchi Ghersi, Sebastiano del Piombo nella villa di Agostino Chigi alla Lungara, in Metafore di un pontificato: Giulio II (1503–1513), eds. Flavia Cantatore, Maria Chiabò, and Paola Farenga, Rome 2010, pp. 403–19 Florence 1984 Raffaello a Firenze: Dipinti e disegni delle collezioni fiorentine, ed. Mina Gregori, exhibition catalogue, Florence, Palazzo Pitti 1984 Florence 1991 Raffaello a Pitti: La Madonna del Baldacchino: Storia e restauro, eds. Marco Chiarini, Marco Ciatti, and Serena Padovani, exhibition catalogue, Florence, Palazzo Pitti 1991 Fischel Oscar Fischel, Raffaels Zeichnungen, 8 vols., Berlin 1913–41 Fischel 1898 Oskar Fischel, Raphaels Zeichnungen: Versuch einer Kritik der bisher veröffentlichen Blätter, Strassburg 1898 Fischel 1915 Oskar Fischel, ‘Raffael und der Apollo von Belvedere’, Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 2 (1912); 17 (1915), pp. 90–101 Fischel 1917 Oskar Fischel, ‘Die Zeichnungen der Umbrer’, Jahrbuch der Preußischen Kunstsammlungen 38 (1917), pp. 1–188 143 Fischel 1935 Oskar Fischel, Raffaelo Santi, in Thieme-Becker, Allgemeines Lexikon der Bildenden Künstler, vol. 29, Leipzig 1935, pp. 433–46 Frankfurt am Main 2012–13 Raphael: Drawings, eds. Joachim Jacoby and Martin Sonnabend, exhibition catalogue, Frankfurt, Städel Museum 2012–13 Fischel 1937 Oskar Fischel, ‘Raphael’s Auxiliary Cartoons’, The Burlington Magazine 71 (1937), pp. 167–68 Franklin 2001 David Franklin, Painting in Renaissance Florence 1500–1550, New Haven 2001 Fischel 1939 Oskar Fischel, ‘Raphael’s Pink Sketch-Book’, The Burlington Magazine 74 (1939), pp. 181–87 Freedberg 1961 Sydney J. Freedberg, Painting of the High Renaissance in Rome and Florence, Cambridge (MA) 1961 Fischel 1945 Oskar Fischel, ‘An Unknown Holy Family by Raphael’, The Burlington Magazine 86 (1945), pp. 82-85 Fischel 1948 Oskar Fischel, Raphael, 2 vols., London 1948 Fischel 1962 Oskar Fischel, Raphael, Berlin 1962 Fischer 1812 Joseph Fischer, Catalog der Gemählde-Gallerie des durchlauchtigen Fürsten Esterházy von Galantha, zu Laxenburg bei Wien, Vienna 1812 Fischer and Rothmüller 1820 Joseph Fischer and Anton Rothmüller, Inventarium No. 10 der fürstlich Esterházyschen Gemählde, Vienna 1820 Forlani Tempesti 1968 Anna Forlani Tempesti, I disegni, in Salmi 1968 Forlani Tempesti 1994 Anna Forlani Tempesti, ‘Studiare dal naturale nella Firenze di fine ’400’, in Florentine Drawing at the Time of Lorenzo the Magnificent: Papers from a Colloquium Held at the Villa Spelman, Florence 1992, ed. Elizabeth Cropper, Bologna 1994, pp. 1–15 Förster 1894 Richard Förster, ‘Die Hochzeit des Alexander und der Roxane in der Renaissance’, Jahrbuch der Preußischen Kunstsammlungen 15 (1894), pp. 182–207 Frankfurt am Main 1999 Von Raffael bis Tiepolo: Italienische Kunst aus der Sammlung des Fürstenhauses Esterházy, ed. István Barkóczi, exhibition catalogue, Frankfurt am Main, Schirn Kunsthalle 1999 Frey 1923 Karl Frey, Der literarische Nachlass Giorgio Vasaris, 2 vols., Munich 1923 Frimmel 1892 Theodor von Frimmel, Kleine Galeriestudien I. Einleitung, die gräflich Schönborn’sche Galerie auf Schloss Weissenstein bei Pommersfelden, Gemäldesammlungen im Bamberg, die Galerie zu Wiesbaden, die Gräflich Nostitz’sche Galerie im Prag, Galerien in Pest, wie die alten Gemälde wander, Bamberg 1892 Frimmel 1904 Theodor von Frimmel, Handbuch der Gemäldekunde, 2nd ed., Leipzig 1904 Frizzoni 1891 Gustavo Frizzoni, Arte Italiana del Rinascimento, Milan 1891 Frommel 2003 Christoph Luitpold Frommel (ed.), The Villa Farnesina in Rome, Modena 2003 Fusco 1979 Laurie Fusco, ‘Pollaiuolo’s Use of the Antique’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 42 (1979), pp. 257–63 Fusco 1982 Laurie Fusco, ‘The Use of Sculptural Models by Painters in Fifteenth-Century Italy’, The Art Bulletin 64 (1982), pp. 175–94 Gamba 1932 Carlo Gamba, Raphaël, Paris 1932 Garas 1960 Klára Garas, Meisterwerke der alten Malerei im Museum der bildenden Künste Budapest, Leipzig 1960 Garas 1983 Klára Garas, ‘Sammlungsgeschichtliche Beiträge zu Raffael: Raffael-Werke in Budapest’, Bulletin du Musée Hongrois des Beaux-Arts 60–61 (1983), pp. 41–81 Garas 1999 Klára Garas, Die Geschichte der Gemäldegalerie Esterházy, in Mraz and Galavics 1999, pp. 101–74 Geneva 1984 Raphäel et la seconde main: Raphäel dans la gravure du XVIe siècle, simulacres et prolifération, Genève et Raphäel, ed. Rainer Michael Mason, exhibition catalogue, Geneva, Cabinet des Estampes 1984 Gentilini 2004 Giancarlo Gentilini, Perugino e la scultura fiorentina del suo tempo, in Teza and Santanicchia 2004, pp. 199–227 Gere and Turner 1983 John A. Gere and Nicholas Turner, Drawings by Raphael from the Royal Library, the Ashmolean, the British Museum, Chatsworth and other English Collections, London 1983 Gerszi 1956 Teréz Gerszi, A múzeum legszebb rajzai, exhibition and check-list, Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts 1956 Gerszi 1999 Gerszi Teréz (ed.), Dürer to Dalì: Master Drawings in the Budapest Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest 1999 Getscher 1999 Robert H. Getscher, ‘The Massacre of the Innocents: An Early Work Engraved by Marcantonio’, Artibus et Historiae 39 (1999), pp. 95–111 Getscher 2003 Robert H. Getscher, An Annotated and Illustrated Version of Giorgio Vasari’s History of Italian and Northern Prints from his Lives of the Artists (1550 and 1568), 2 vols., Lewiston 2003 Gibson-Wood 2003 Carol Gibson-Wood, A Judiciously Disposed Collection. Jonathan Richardson Senior’s Cabinet of Drawings, in Collecting Prints and Drawings in Europe, c. 1500–1750, eds. Christopher Baker, Caroline Elam, and Genevieve Warwick, Aldershot 2003 144 Gilbert 1986 Creighton E. Gilbert, Signorelli and Young Raphael, in Beck 1986, pp. 109–24 Grimm 1886 Herman Grimm, Das Leben Raphaels, 2nd ed., Berlin 1886 Giles 1999 Laura M. Giles, ‘A Drawing by Raphael for the Sala di Costantino’, Master Drawings 37 (1999), pp. 156–64 Gruyer 1869 François-Anatole Gruyer, Les vierges de Raphaël et l’iconographie de la Vierge, 3 vols., Paris 1869 Giovio 1999 Paolo Giovio, Scritti d’arte: Lessico ed ecfrasi, ed. Sonia Mafei, Pisa 1999 Gruyer 1891 François-Anatole Gruyer, Voyage autour du salon carré au musée du Louvre, Paris 1891 Glasser 1965 Hannelore Glasser, Artist’s Contracts of the Early Renaissance, PhD dissertation, New York, Columbia University 1965 Günther 2001 Hubertus Günther, ‘Amor und Psyche: Raffaels Freskenzyklus in der Gartenloggia der Villa des Agostino Chigi und die Fabel von Amor und Psyche in der Malerei der italienischen Renaissance’, Artibus et historiae 44 (2001), pp. 149–66 Gnann and Plomp 2012–13 Achim Gnann and Michiel C. Plomp, Raphael and his School, exhibition catalogue, Haarlem, Teylers Museum 2012–13 Gombrich 1966 Ernst H. Gombrich, Leonardo’s Methods of Working out Compositions, in Norm and Form on the Art of the Renaissance I, London and New York 1966 Gonda 1999 Zsuzsa Gonda, Die graphische Sammlung des Fürsten Nikolaus Esterházy, in Mraz and Galavics 1999, pp. 175–220 Gould 1982 Cecil Gould, ‘Raphael versus Giulio Romano: The Swing Back’, The Burlington Magazine 124 (1982), pp. 479–87 Gramaccini and Meier 2009 Norberto Gramaccini and Hans Jacob Meier, Die Kunst der Interpretation: Italienische Reproduktionsgrafik 1485–1600, Berlin and Munich 2009 Graul 1893 Richard Graul, ‘Des Giovan Antonio de’ Bazzi (Sodoma): Vermählung Alexanders mit Roxane’, Die Graphischen Künste 16 (1893), pp. 45–53 Harding et al. 1989 Eric Harding et al., ‘The Restoration of the Leonardo Cartoon’, National Gallery Technical Bulletin 13 (1989), pp. 4–27 Harprath 1985 Richard Harprath, ‘Raffaels Zeichnung Merkur und Psyche: Aus Chatsworth neuerworben für München’, Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 48 (1985), pp. 407–33 Hartt 1958 Frederick Hartt, Giulio Romano, 2 vols., New Haven 1958 Hartt 1971 Frederick Hartt, The Drawings of Michelangelo, London 1971 Haskell and Penny 1981 Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, Taste and the Antique, New Haven and London 1981 Hayum 1966 Andrée Hayum, ‘A New Dating for Sodoma’s Frescoes in the Villa Farnesina’, The Art Bulletin 48 (1966), pp. 215–17 Gregori 1987 Mina Gregori, Considerazioni su una mostra, in Sambucco and Strocchi 1987, pp. 649–55 Henry 1993 Tom Henry, ‘Signorelli, Raphael and a Mysterious Pricked Drawing in Oxford’, The Burlington Magazine 135 (1993), pp. 612–19 Gregory 2012 Sharon Gregory, Vasari and the Renaissance Print, Farnham 2012 Henry 1999 Tom Henry, Nuovi documenti su Giovanni Santi, in Varese 1999, pp. 223–26 Henry 2002 Tom Henry, ‘Raphael’s Altar-Piece Patrons in Città di Castello’, The Burlington Magazine 144 (2002), pp. 268–78 Henry 2004 Tom Henry, ‘Raphael and Siena’, Apollo 160 (2004), pp. 51–56 Henry 2008 Tom Henry, Perugia 1502, in Perugia 2008, pp. 121–29 Henry 2009 Tom Henry, Raffaello e Signorelli, in Urbino 2009, pp. 78–83 Henry 2012 Tom Henry, The Life and Art of Luca Signorelli, New Haven and London 2012 Henry and Joannides 2012–13 Tom Henry and Paul Joannides: Late Raphael, exhibition catalogue, Madrid, Museo del Prado and Paris, Musée du Louvre 2012–13 Henry and Kanter 2002 Tom Henry and Laurence B. Kanter, Luca Signorelli: The Complete Paintings, London 2002 Hiller von Gaertringen 1997 Rudolf Hiller von Gaertringen, On Perugino’s ReUses of Cartoons, in Dessin sous-jacent et technologie de la peinture, Louvain-la-Neuve 1997, pp. 223–30 Hiller von Gaertringen 1999 Rudolf Hiller von Gaertringen, Raffaels Lernerfahrungen in der Werkstatt Peruginos: Kartonverwendung und Motivübernahme im Wandel, Munich and Berlin 1999 Hiller von Gaertringen 2004 Rudolf Hiller von Gaertringen, Uso e riuso cartone nell’opera del Perugino: L’arte fra vita contemplativa e produttività, in Teza és Santanicchia 2004, pp. 335–50 Hind 1912 Arthur Mayger Hind, Marcantonio and Italian Engravers and Etchers of the Sixteenth Century, London 1912 Hirst 2000 Michael Hirst, ‘Michelangelo in Florence: David in 1503 and Hercules in 1506’, The Burlington Magazine 142 (2000), pp. 487–92 145 Hirst and Dunkerton 1994 Michael Hirst and Jill Dunkerton, The Young Michelangelo: The Artist in Rome 1496–1501, exhibition catalogue, London, The National Gallery 1994 Hirth 1898 Herbert Hirth, Marcanton und sein Stil: Eine kunstgeschichtliche Studie, dissertation, Munich 1898 (http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/0007/ bsb00074938/images/) Hoffmann 1929–30 Edith Hoffmann, ‘Újabb meghatározások a rajzgyűjteményben’, Az Országos Magyar Szépművészeti Múzeum Évkönyvei 6 (1929–30), pp. 129–206 Hoffmann 1930 Edith Hoffmann, Miniatúrák és olasz rajzok, exhibition and check-list, Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts 1930 Hoffmann 1934 Edith Hoffmann, Rajzoló eljárások, exhibition and check-list, Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts 1934 Hoffmann 1936 Edith Hoffmann, Legszebb külföldi rajzok, exhibition and check-list, Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts 1936 Holmes 2004 Megan Holmes, Copying Practices and Marketing Strategies in a Fifteenth-Century Florentine Painter’s Workshop, in The Politics of Influence. Artistic Exchange in Renaissance Italy, eds. Stephen J. Campbell and Stephen J. Milner, Cambridge 2004, pp. 38–74 Holo 1978–79 Selma Holo, ‘A Note on the Afterlife of the Crouching Aphrodite in the Renaissance’, J. Paul Getty Museum Journal 6 (1978–79), pp. 23–36 Höper 2001 Corinna Höper, Raffael und die Folgen: Das Kunstwerk in Zeitaltern seiner graphischen Reproduzierbarkeit, Stuttgart 2001 Hyde Minor 1999 Vernon Hyde Minor, Baroque and Rococo: Art and Culture, New York 1999 Jaffé 1994 Michael Jaffé, The Devonshire Collection of Italian Drawings: Roman and Neapolitan Schools, London 1994 Kelber 1979 Wilhelm Kelber, Raphael von Urbino: Leben und Werk, Stuttgart 1979 Janitschek 1884 Hubert Janitschek, ‘Compte rendu de l’etude de Pulszky’, Repertorium für Kunstwissenschaft (7) 1884, pp. 226–31 Kinkead 1970 Duncan T. Kinkead, ‘An Iconographic Note on Raphael’s Galatea’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 33 (1970), pp. 313–15 Jerusalem 2011 The Prince and the Paper: Masterworks from the Esterházy Collection, exhibition catalogue, Jerusalem, Israel Museum 2011 Knab, Mitsch, and Oberhuber 1983 Eckhart Knab, Erwin Mitsch, and Konrad Oberhuber, Raphael: Die Zeichnungen, Stuttgart 1983 Joannides 1983 Paul Joannides, The Drawings of Raphael, with a Complete Catalogue, Oxford 1983 Joannides 1993 Paul Joannides, ‘Raphael, his Studio and his Copyists’, Paragone 41–42 (1993), pp. 3–29 Joannides 2000a Paul Joannides, ‘Raphael and his Circle’, Paragone 601 (2000), pp. 3–42 Joannides 2000b Paul Joannides, ‘Giulio Romano in Raphael’s Workshop’, Quaderni di Palazzo Tè 8 (2000), pp. 35–45 Joannides 2002–3 Paul Joannides, Raphael and his Age: Drawings from the Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille, exhibition catalogue, Cleveland, Cleveland Museum of Art and Lille, Palais des Beaux-Arts 2002–3 Johnson 1982 Jan Johnson, ‘I chiaroscuri di Ugo da Carpi’, Il conoscitore di stampe 57–58 (1982), pp. 2–87 Jones and Penny 1983 Roger Jones and Nicholas Penny, Raphael, New Haven and London 1983 Joost-Gaugier 2002 Christiane L. Joost-Gaugier, Raphael’s Stanza della Segnatura: Meaning and Invention, Cambridge (MA) and New York 2002 Karl 1894 Károly Karl [Charles, Frank Tryon], Raphael’s Madonnas and Other Great Pictures Reproduced from the Original Paintings, with a Life of Raphael and an Account of his Chief Works, London 1894 Knackfuß 1895 Hermann Knackfuß, Raffael, 2nd ed., Bielefeld and Lepizig 1895 Koopmann 1886 Wilhelm Koopmann, ‘Compte rendu de l’œuvre de Grimm’, Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst 1886 Koopmann 1891 Wilhelm Koopmann, ‘Einige weniger bekannte Handzeichnungen Raphaels’, Jahrbuch der Preußischen Kunstsammlungen 12 (1891), pp. 40–49 Kremeier 1998 Jarl Kremeier, ‘Raffaels Madonna Esterházy Beobachtungen zu Komposition und Datierung’, Belvedere 4 (1998), pp. 36–47 Krems 1996 Eva-Bettina Krems, Raffaels Marienkrönung im Vatikan, Frankfurt am Main 1996 Kristeller 1907 Paul Kristeller, ‘Marcantons Beziehungen zu Raffael’, Jahrbuch der Preußischen Kunstsammlungen 28 (1907), pp. 199–29 Kruft 1970 Hanno-Walter Kruft, ‘Concerning the Date of the Codex Escurialensis’, The Burlington Magazine 112 (1970), pp. 44–47 Kwakkelstein 2002 Michael W. Kwakkelstein, ‘The Model’s Pose: Raphael’s Early Use of Antique and Italian Art’, Artibus et Historiae 23 (2002), pp. 37–60 Kwakkelstein 2004 Michael W. Kwakkelstein, ‘Perugino in Verrocchio’s Workshop: The Transmission of an Antique Striding Stance’, Paragone 55–56 (2004), pp. 47–61 146 Kwakkelstein 2007 Michael W. Kwakkelstein, The Development of the Figure Study in the Early Work of Raphael, in The Translation of Raphael’s Roman Style, ed. Henk Th. van Veen, Leuven 2007, pp. 21–33 La Malfa 2008 Claudia La Malfa, Invenzioni, modelli e copie: Pintoricchio disegnatore e il rapporto con Perugino, la bottega umbra del primo Rinascimento e Raffaello, in Perugia 2008, pp. 347–65 Lambert 1987 Susan Lambert, The Image Multiplied: Five Centuries of Printed Reproductions of Paintings and Drawings, London 1987 Landau 1983 David Landau, ‘Vasari, Prints and Prejudice’, The Oxford Art Journal 6 (1983), pp. 3–10 Landau and Parshall 1994 David Landau and Peter Parshall, The Renaissance Print 1470–1550, New Haven and London 1994 Léderer 1907 Sándor Léderer, A Szépművészeti Múzeum milánói mesterei és Leonardo da Vinci, Budapest 1907 Lemgo and Prague 2008 Hans Rottenhammer–begehrt–ergessen– neu entdeckt, ed. Heiner Borggrefe, exhibition catalogue, Lemgo, Weserrenaissance-Museum Schloss Brake and Prague, Nationalgalerie 2008 Loewy 1896 Emanuele Loewy, ‘Di alcune composizioni di Raffaello ispirate ai monumenti antichi’, Archivo storico dell’arte 2 (1896), pp. 241–51 London 2010 Treasures from Budapest: European Masterpieces from Leonardo to Schiele, ed. David Ekserdjian, exhibition catalogue, London, Royal Academy of Arts 2010 London and Florence 2010–11 Fra Angelico to Leonardo: Italian Renaissance Drawings, eds. Hugo Chapman and Marzia Faietti, exhibition catalogue, London, British Museum and Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi 2010–11 Longhi 1955 Roberto Longhi, ‘Percorso di Raffaello giovine’, Paragone 65 (1955), pp. 8–23 Luchs 1983 Alison Luchs, ‘A Note on Raphael’s Perugian Patrons’, The Burlington Magazine 125 (1983), pp. 29–31 Matarazzo 1905 Francesco Matarazzo, Chronicles of the City of Perugia, 1492–1503, London 1905 Lübke 1875 Wilhelm Lübke, Rafael-Werk: Sämmtliche Tafelbilde und Fresken des Meisters in Nachbildungen nach Kupferstichen und Photographien, 5 vols., Dresden 1875 Matthew 1998 Louisa Matthew, ‘The Painter’s Presence: Signatures in Venetian Renaissance Pictures’, The Art Bulletin 80 (1998), pp. 616–48 Lützow 1876 Carl von Lützow, ‘Korrespondenz’, Kunst-Chronik 11 (1876), pp. 6–10 Meller 1911 Simon Meller, Külföldi mesterek rajzai XIV–XVIII. század, exhibition and check-list, Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts 1911 Magnusson 1992 Börje Magnusson, Rafael: Teckningar, exhibition catalogue, Stockholm, Nationalmuseum 1992 Meller 1915 Simon Meller, Az Esterházy-képtár története, Budapest 1915 Mancinelli 1986 Fabrizio Mancinelli, The Coronation of the Virgin by Raphael, in Beck 1986, pp. 127–36 Meyer zur Capellen 1996 Jürg Meyer zur Capellen, Raphael in Florence, London 1996 Mancinelli and Nesselrath 1993 Fabrizio Mancinelli and Arnold Nesselrath, La Stanza dell’Incendio, in Corini 1993, pp. 293–343 Meyer zur Capellen 2001 Jürg Meyer zur Capellen, Raphael: A Critical Catalogue of his Paintings I: The Beginnings in Umbria and Florence ca. 1500–1508, Landshut 2001 Mancini 2004 Francesco Federico Mancini, Considerazioni sulla bottega umbra del Perugino, in Teza and Santanicchia 2004, pp. 329–34 Mansuelli 1958 Guido A. Mansuelli, Galleria degli Uffizi: Le Sculture I, Rome 1958 Marani 2003–4 Pietro C. Marani, Imita quanto puoi li Greci e Latini: Leonardo da Vinci and the Antique, in Athens 2003–4, pp. 475–78 Marek 1984 Michaela Marek, ‘Raffaels Loggia di Psiche in der Farnesina: Überlegungen zu Rekonstruktion und Deutung’, Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen N.F. 26 (1984), pp. 257–90 Meyer zur Capellen 2005 Jürg Meyer zur Capellen, Raphael: A Critical Catalogue of his Paintings II: The Religious Paintings, ca. 1508–1520, Landshut 2005 Middeldorf 1945 Ulrich Middeldorf, Raphael’s Drawings, New York 1945 Minghetti 1885 Marco Minghetti, Raffaello, Bologna 1885 Mitsch 1983 Erwin Mitsch, Raphael in der Albertina: Aus Anlaß der 500. Geburtstages des Künstlers, exhibition catalogue, Vienna, Albertina 1983 Marle 1923–38 Raimond van Marle, The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting, 19 vols., Hague 1923–38 Monbeig-Goguel 1984 Catherine Monbeig-Goguel, ‘The Drawings of Raphael, with a Complete Catalogue by Paul Joannides and Raphael: Die Zeichnungen by Erwin Knab et al.’, The Burlington Magazine 126 (1984), pp. 438–40 Massari and Prosperi Valenti Rodinò 1989 Stefania Massari and Simonetta Prosperi Valenti Rodinò, Tra mito e allegoria: Immagini a stampe nel ,500 e ,600, exhibition catalogue, Rome, Istituto Nazionale per la Grafica 1989 Monbeig-Goguel 1987 Catherine Monbeig-Goguel, Le tracé invisible des dessins de Raphaël: Pour une problématique des techniques graphiques à la Renaissance, in Sambucco and Strocchi 1987, pp. 377–89 147 Montreal 2002 Italian Old Masters from Raphael to Tiepolo: The Collection of the Budapest Museum of Fine Arts, exhibition catalogue, Montreal, Museum of Fine Arts 2002 Natale 2005–6 Mauro Natale, Rafael: Retrato de un joven, exhibition catalogue, Madrid, Museo ThyssenBornemisza 2005–6 Nesselrath 2004c Arnold Nesselrath, ‘Lotto as Raphael’s Collaborator in the Stanza di Eliodoro’, The Burlington Magazine 146 (2004), pp. 732–41 Móré 1987 Miklós Móré, ‘Remarques sur l’etat anterieur des tableaux voles et recuperes de Raffaello Santi et de Jacopo Tintoretto: Compte-rendu de la restauration des degats causes par ce vol’, Bulletin du Musée Hongrois des Beaux-Arts 68–69 (1987), pp. 103–29 Nathan 1995 Johannes Nathan, The Working Methods of Leonardo da Vinci and their Relationship to Previous Artistic Practice, PhD dissertation, London, Courtauld Institute of Art 1995 Nesselrath 2013 Arnold Nesselrath, L’antico vissuto: La stufetta del cardinal Bibbiena, in Pietro Bembo e l’invenzione del Rinascimento, eds. Guido Beltramini, Davide Gasparotto, and Adolfo Tura, exhibition catalogue, Padua, Palazzo del Monte di Pietà 2013, pp. 284–91 Morelli 1890 Giovanni Morelli [Ivan Lermolieff], Kunstkritische Studien über italienische Malerei: Die Galerien Borghese und Doria Pamfili in Rom, Leipzig 1890 Morello 1985–86 Giovanni Morello, Raffaello e la Roma dei Papi, exhibition catalogue, Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana 1985–86 Mozo 2012–13 Ana González Mozo, Raphael’s Painting Technique in Rome, in Henry and Joannides 2012–13, pp. 319–49 Mraz and Galavics 1999 Gerda Mraz and Géza Galavics (eds.), Von Bildern und anderen Schätzen: Die Sammlungen der Fürsten Esterházy, Vienna 1999 Müntz 1885 Eugène Müntz, ‘Les dessins de la jeunesse de Raphaël’, Gazette des Beaux-Arts 1885 Müntz 1886 Eugène Müntz, Raphaël: sa vie, son œuvre, et son temps, Paris 1886 Nagler 1835–14 Georg Kaspar Nagler, Neues allgemeines KünstlerLexikon, oder Nachrichten von dem Leben und den Werken der Maler, Bildhauer, Baumeister, Kupferstecher, Formschneider, Lithographen, Zeichner, Medailleure, Elfenbeinarbeiter, etc., 25 vols., Munich 1835–1914 Nees 1978 Lawrence Nees, ‘Le Quos Ego de Marc-Antoine Raimondi’, Nouvelles de l’estampe 40–41 (1978), pp. 18–29 Nesselrath 1986 Arnold Nesselrath, Raphael’s Archeological Method, in Rome 1986, pp. 357–69 Nesselrath 1992 Arnold Nesselrath, ‘Art-historical Findings during the Restoration of the Stanza dell’Incendio’, Master Drawings 30 (1992), pp. 31–60 Nesselrath 1993 Arnold Nesselrath, La Stanza di Eliodoro, in Corini 1993, pp. 203–45 Nesselrath 1996a Arnold Nesselrath, Il Codice Escurialense, in Domenico Ghirlandaio 1449–1494, eds. Wolfram Prinz and Max Seidel, (Atti del Convegno Internazionale Firenze, 16–18 ottobre 1994), Florence 1996, pp. 175–98 Nesselrath 1996b Arnold Nesselrath, Raphael’s School of Athens, Vatican 1996 Nesselrath 2000 Arnold Nesselrath, ‘Lorenzo Lotto in the Stanza della Segnatura’, The Burlington Magazine 142 (2000), pp. 4–12 Nagler 1836 Georg Kaspar Nagler, Rafael als Mensch und Künstler, Munich 1836 Nesselrath 2004a Arnold Nesselrath, Raphael and Pope Julius II, in Chapman, Henry, and Plazzotta 2004, pp. 281–93 Nanni and Monaco 2007 Romano Nanni and Chiara Monaco, Leda: Storia di un mito dalle origini a Leonardo, Florence 2007 Nesselrath 2004b Arnold Nesselrath, Il Vaticano–La Cappella Sistina: Il Quattrocento, Parma 2004 O’Malley 2005 Michelle O’Malley, The Business of Art: Contracts and the Commissioning Process in Renaissance Italy, New Haven and London 2005 O’Malley 2007 Michelle O’Malley, ‘Quality, Demand, and Pressures of Reputation: Rethinking Perugino’, The Art Bulletin 89 (2007), pp. 674–93 Oberhuber 1966 Konrad Oberhuber, Renaissance in Italien: 16. Jahrhundert, exhibition catalogue, Vienna, Albertina 1966 Oberhuber 1972 Konrad Oberhuber, Raphaels Zeichnungen: Abteilung IX, Entwürfe zu Werken Raphaels und seiner Schule im Vatikan 1511–12 bis 1520, Berlin 1972 Oberhuber 1978 Konrad Oberhuber, ‘The Colonna Altarpiece in the Metropolitan Museum and Problems of the Early Style of Raphael’, The Metropolitan Museum Journal 12 (1978), pp. 55–90 Oberhuber 1982 Konrad Oberhuber, Raffaello, Milan 1982 Oberhuber 1983 Konrad Oberhuber, Späte Römische Jahre, in Knab, Mitsch, and Oberhuber 1983, pp. 113–44 Oberhuber 1984–85 Konrad Oberhuber, Raffaello e l’incisione, in Vatican 1984–85, pp. 333–42 Oberhuber 1985 Konrad Oberhuber, ‘The Drawings of Dürer and Raphael’, Drawing 7 (1985), pp. 25–29 148 Oberhuber 1986a Konrad Oberhuber, Raphael and Pintoricchio, in Beck 1986, pp. 155–72 Oberhuber 1986b Konrad Oberhuber, Raphael’s Drawings for the Loggia of Psyche in the Farnesina, in Rome 1986, pp. 189–216 Oberhuber 1988 Konrad Oberhuber, Marcantonio Raimondi: Gli inizi a Bologna ed il primo periodo romano, in Bologna 1988, pp. 51–88 Oberhuber 1998 Konrad Oberhuber, Die Werkstatt Raffaels, in Künstlerwerksätten der Renaissance, (ed.) Roberto Casselli, Milan, Zürich, and Düsseldorf 1998, pp. 257–74 Oberhuber 1999 Konrad Oberhuber, Raphael: The Paintings, Munich, London, and New York 1999 Oberhuber and Gnann 1999 Konrad Oberhuber and Achim Gnann: Raphael und der klassische Stil in Rom: 1515–1527, exhibition catalogue, Mantua, Palazzo Tè and Vienna, Albertina 1999 Olszewski 2009 Edward J. Olszewski, ‘Bring on the Clones. Pollaiuolo’s Battle of Ten Nude Men’, Artibus et Historiae 30 (2009), pp. 9–38 Oppé 1909 Adolf Paul Oppé, Raphael, London 1909 Ormós 1864 Zsigmond Ormós, A herczeg Esterházy képtár műtörténelmi leírása, Pest 1864 Ortolani 1945 Sergio Ortolani, Raffaello, 2nd ed., Bergamo 1945 Osano 1996 Shigethosi Osano, ‘Due ’Marsia’ nel giardino di Via Larga: La ricezione del decor dell’antichità romana nella collezione medicea di sculture antiche’, Artibus et Historiae 17 (1996), pp. 95–120 Padovani 2005 Serena Padovani, ‘I ritratti Doni: Raffaello e il suo eccentrico amico, il Maestro di Serumido’, Paragone 56–61 (2005), pp. 3–26 Paris 2011 Le naissance du Musèe les Esterházy Collectionneurs, eds. Marc Restellini and Orsolya Radványi, exhibition catalogue, Paris, Pinacothèque de Paris 2011 Pest 1869 Catalog der Gemälde-Gallerie Seiner Durchlaucht des Fürsten Nicolaus Eszterházy von Galantha in Pest, Academie-Gebäude, Pest 1869 Parker 1939–40 Karl T. Parker, ‘Some Observations on Oxford Raphaels’, Old Master Drawings 54–56 (1939–40), pp. 34–43 Pest 1871 A Magyar Akadémia épületében lévő Országos Képtár műsorozata, Pest 1871 Parker 1956 Karl T. Parker, Catalogue of the Collection of Drawings in the Ashmolean Museum: Vol. II: Italian Schools, Oxford 1956 Passavant 1839–58 Johann David Passavant, Rafael von Urbino und sein Vater Giovanni Santi, 4 vols., Leipzig 1839–58 Passavant 1860 Johann David Passavant, Raphaël d’Urbin et son père Giovanni Santi, 2 vols., Paris 1860 Passavant 1860–64 Johann David Passavant, Le peintre-graveur, 6 vols., Leipzig 1860–64 Pedretti 1989 Carlo Pedretti, Raphael: His Life and Work in the Splendors of the Italian Renaissance, Florence 1989 Penny 1992 Nicholas Penny, ‘Raphael’s Madonna dei garofani Rediscovered’, The Burlington Magazine 134 (1992), pp. 67–81 Peregriny 1909 János Peregriny, Az Országos Magyar Szépművészeti Múzeum állagai I, Budapest 1909 Perugia 2004 Perugino: Il divin pittore, eds. Vittoria Garibaldi, Francesco Federico Mancini, and Alessandro Marabottoni, exhibition catalogue, Perugia, Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria 2004 Perugia 2008 Pintoricchio, eds. Vittoria Garibaldi and Francesco Federico Mancini, exhibition catalogue, Perugia, Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria 2008 Pest 1865 Műsorozata a Magyar Tudományos Akadémia palotájában elhelyezett Esterházy herczegi képtárnak, Pest 1865 Pest 1873 Catalog der Landes-Gemälde-Gallerie in AcademieGebäude, Pest 1873 Petrucci 1964 Alfredo Petrucci, Panorama della incisione italiana: Il cinquecento, Rome 1964 Pigler 1937 Andor Pigler, Országos Magyar Szépművészeti Múzeum: A Régi Képtár katalógusa, Budapest 1937 Pigler 1954 Andor Pigler, Országos Szépművészeti Múzeum: A Régi Képtár katalógusa, Budapest 1954 Pigler 1967 Andor Pigler, Katalog der Galerie Alter Meister Budapest, Budapest 1967 Plemmons 1978 Barbara Mathilde Plemmons, Raphael 1504–1508, PhD dissertation, Los Angeles, University of Carolina 1978 Pogány-Balás 1972 Edith Pogány-Balás, ‘L’influence des gravures de Mantegna sur la composition de Raphael et de Raimondi le Massacre des Innocents’, Bulletin du Musée Hongrois des Beaux-Arts 38 (1972), pp. 25–40 Pon 2004a Lisa Pon, Raphael, Dürer, and Marcantonio Raimondi: Copying and the Italian Renaissance Print, New Haven 2004 Pon 2004b Lisa Pon, ‘Parmigianino and Raphael: A Note on the Foreground Baby from the Massacre of the Innocents’, Apollo 159 (2004), pp. 6–7 Pope-Hennessy 1971 John Pope-Hennessy, Raphael, London 1971 Pouncey and Gere 1962 Philip Pouncey and John Gere, Italian Drawings in the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum: Raphael and his Circle, 2 vols., London 1962 149 Prohaska 1990 Wolfgang Prohaska, The Restoration and Scientific Examination of Raphael’s Madonna in the Meadow, in Shearman and Hall 1990, pp. 57–64 Pulszky 1881a Károly Pulszky, A Magyar Országos Képtár ideiglenes lajstroma, Budapest 1881 Pulszky 1881b Károly Pulszky, ‘Raphael Santi az Országos Képtárban’, Archaeológiai Értesítő N. S. 1 (1881), pp. 40–101 Pulszky 1882 Károly Pulszky, ‘Raphael Santi in der Ungarischen Reichs-Gallerie’, Ungarische Revue 2 (1882), pp. 297–43 Pulszky 1888 Károly Pulszky, Országos Képtár I: A Képgyűjtemény leíró lajstroma, Budapest 1888 Quatremère de Quincy 1829 Antoine Chrysostôme Quatremère de Quincy, Istoria della vita e delle opere di Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino. Voltata in Italiano, corretta, illustrata ed ampliata per cura di Francesco Longhena, Milano 1829 Quedneau 1979 Rolf Quedneau, Die Sala di Costantino im Vatikanischen Palast: Zur Dekoration der beiden Medici-Päpste Leo X und Clemens VII, Hildesheim and New York 1979 Quedneau 1986 Rolf Quedneau, ‘Aspects of Raphael’s ultima maniera in the Light of the Sala di Costantino’, in Rome 1986, pp. 245–57 Ragghianti and Dalli Regoli 1975 Carlo L. Ragghianti and Gigetta Dalli Regoli, Firenze 1470–1480: Disegni dal modello, Pisa 1975 Ray 1979 Stefano Ray, ‘Raffaello; ambiente e città: Dai documenti iconografici e dagli scritti 2’, Storia della città 10 (1979), pp. 65–74 Rome 1985 Grazia Bernini Pezzini, Stefania Massari et al., Raphael invenit: Stampe da Raffaello nelle collezioni dell’Istituto Nazionale per la Grafica, exhibition catalogue, Rome, Calcografia Nazionale 1985 Rowland 1986 Ingrid D. Rowland, ‘Render Unto Caesar the Things Which are Caesar’s: Humanism and the Arts in the Patronage of Agostino Chigi’, Renaissance Quarterly 39 (1986), pp. 673–730 Rome 1986 Raffaello a Roma: Il convegno del 1983, eds. Christoph Luitpold Frommel and Matthias Winner, Rome 1986 Roy and Spring 2007 Ashok Roy and Marika Spring (eds.), Raphael’s Painting Technique: Working Practices Before Rome, Florence 2007 Rome 2006 Raffaello da Firenze a Roma, ed. Anna Coliva, exhibition catalogue, Rome, Galleria Borghese 2006 Rome and Paris 1998 Francesco Salviati (1510–1563) ou la Bella Maniera, ed. Catherine Monbeig-Goguel, exhibition catalogue, Rome, Accademia di Francia and Paris, Musée du Louvre 1998 Rosand 1984 David Rosand, ‘Raphael, Marcantonio, and the Icon of Pathos’, Source: Notes in the History of Art 3 (1984), pp. 34–52 Rosand 1988 David Rosand, ‘Raphael Drawings Revisited’, Master Drawings 26 (1988), pp. 358–63 Rosenberg 1904 Adolf Rosenberg, Raffael, des meisters Gemälde, Stuttgart and Leipzig 1904 Rosenberg 1986 Charles M. Rosenberg, Raphael and the Florentine istoria, in Beck 1986, pp. 175–87 Rosenberg and Gronau 1923 Adolf Rosenberg and Georg Gronau, Raffael, des meisters Gemälde, 4th ed., Stuttgart and Leipzig 1923 Roskill 1968 Mark W. Roskill, Dolce’s ’Aretino’ and Venetian Art Theory of the Cinquecento, New York 1968 Rehberg 1824 Friedrich Rehberg, Rafael Sanzio aus Urbino, Munich 1824 Rouillard 2001 Philippe Rouillard, ‘Marc-Antoine Raimondi: Les Massacres des Innocents’, Nouvelles de l’estampe 179–80 (2001), pp. 12–32 Rohden and Winnefeld 1911 Hermann von Rohden and Hermann Winnefeld, Architektonische Römische Tonreliefs: Der Kaiserzeit, 2 vols., Berlin and Stuttgart 1911 Rowland 1984 Ingrid D. Rowland, ‘Some Panegyrics to Agostino Chigi’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 47 (1984), pp. 194–99 Roy, Spring, and Plazzotta 2004 Ashok Roy, Marika Spring, and Carol Plazzotta, ‘Raphael’s Early Work in the National Gallery: Paintings before Rome’, National Gallery Technical Bulletin 25 (2004), pp. 4–35 Rubin 1995 Patricia Lee Rubin, Giorgio Vasari: Art and History, New Haven and London 1995 Rubin and Wright 1999 Patricia L. Rubin and Alison Wright, Renaissance Florence: The Art of the 1470s, London 1999 Ruland 1876 Charles Ruland, The Works of Raphael Santi da Urbino as Represented in the Raphael Collection in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle, London 1876 Salmi 1968 Mario Salmi (ed.), Raffaello: L’opera, le fonti, la fortuna, 2 vols., Novara 1968 Salmi 1969 Mario Salmi (ed.), The Complete Work of Raphael, New York 1969 Sambucco and Strocchi 1987 Micaela Sambucco Hamoud and Maria Letizia Strocchi (eds.): Studi su Raffaello (Atti del Congresso Internazionale di Studi, Urbino–Firenze, 6–14 aprile 1984), Urbino 1987 Sartore 2004 Alberto Maria Sartore, Nuovi documenti su alcune committenze a Perugino, in Perugia 2004, pp. 603–6 Sartore 2008 Alberto Maria Sartore, ‘New Documents for Raphael’s Coronation of the Virgin and Perugino’s Corciano Assumption of the Virgin’, The Burlington Magazine 150 (2008), pp. 669–72 150 Sartore 2011 Alberto Maria Sartore, ‘Begun by Master Raphael: The Monteluce Coronation of the Virgin’, The Burlington Magazine 153 (2011), pp. 387–91 Scarpellini 1984 Pietro Scarpellini, Perugino, Milan 1984 Scheller 1995 Robert W. Scheller, Exemplum: Model Book Drawings and the Practice of Artistic Transmission in the Middle Ages (ca. 900–ca. 1470), Amsterdam 1995 Schmitt 1970 Annegrit Schmitt, ‘Römische Antikensammlungen im Spiegel eines Musterbuchs der Renaissance’, Münchner Jahrbuch der bildenden Kunst 21 (1970), pp. 99–128 Shearman 1965 John Shearman, Raphael’s Unexecuted Projects for the Stanze, in Walter Friedlaender zum 90. Geburtstag: Eine Festgabe seiner europäischen Schüler, Freunde und Verehrer, eds. Georg Kauffmann and Willibald Sauerländer, Berlin 1965, pp. 158–80 Shearman 1967 John Shearman, Mannerism, London 1967 Shearman 1971 John Shearman, ‘The Vatican Stanze: Functions and Decoration’, Proceedings of the British Academy 57 (1971), pp. 369–424 Shearman 1972 John Shearman, Raphael’s Cartoons in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen and the Tapestries for the Sistine Chapel, London 1972 Schönbrunner and Meder 1895–1908 Joseph Schönbrunner and Joseph Meder, Handzeichnungen Alter Meister aus der Albertina und anderen Sammlungen, 12 vols., Vienna 1895–1908 Shearman 1975 John Shearman, ‘The Florentine Entrata of Leo X, 1515’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 38 (1975), pp. 136–54 Schöne 1958 Wolfgang Schöne, Raphael, Berlin 1958 Shearman 1977 John Shearman, ‘Raphael, Rome, and the Codex Escurialensis’, Master Drawings 15 (1977), pp. 107–46 Schulz 1962 Jürgen Schulz, ‘Pinturicchio and the revival of Antiquity’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 16 (1962), pp. 35–55 Shearman 1983 John Shearman, ‘The Organization of Raphael’s Workshop’, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 10 (1983), pp. 40–57 Schwartz 1997 Michael Schwartz, ‘Raphael’s Authorship in the Expulsion of Heliodorus’, The Art Bulletin 79 (1997), pp. 466–92 Shearman 1993 John Shearman, Gli appartamenti di Giulio II e Leone X, in Corini 1993, pp. 15–37 Serafini 2004 Alessandro Serafini in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, ed. Alberto M. Ghisalberti, Rome 1960– (vol. 61, 2004) (http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/ ignazio-enrico-hugford_Dizionario-Biografico) Shearman 1959 John Shearman, ‘Giulio Romano (review)’, The Burlington Magazine 101 (1959), pp. 456–60 Shearman 1964 John Shearman, ‘Die Loggia der Psyche in der Villa Farnesina und die Probleme der letzten Phase von Raffaels graphischem Stil’, Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien 60 (1964), pp. 59–100 Shearman 2003 John Shearman, Raphael in Early Modern Sources: 1483–1602, New Haven and London 2003 Shearman and Hall 1990 John Shearman and Marcia B. Hall (eds.), The Princeton Raphael Symposium: Science in the Service of Art History, Princeton (NJ) 1990 Shinjuku 1992–93 European Landscapes from Raphael to Pissarro, ed. Ildikó Ember, exhibition catalogue, Shinjuku, Mitsukoshi Museum of Art 1992–93 Shoemaker 1981 Innis H. Shoemaker, The Engravings of Marcantonio Raimondi, exhibition catalogue, Kansas, Spencer Museum of Art 1981 Silvestrelli 2005 Maria Rita Silvestrelli, ‘Pintoricchio: Il contratto della pala della Fratta e altre committenze perugine’, I Lunedì della Galleria 8 (2005), pp. 63–72 Smentek 2008 Kristel Smentek, ‘The Collector’s Cut: Why PierreJean Mariette Tore up His Drawings and Put Them Back Together Again’, Master Drawings 46 (2008), pp. 36–60 Sonnenburg 1983 Hubertus von Sonnenburg, Raphael in der Alten Pinakothek: Geschichte und Wiederherstellung des ersten Raphael-Gemäldes in Deutschland und der von König Ludwig I. erworbenen Madonnenbilder, Munich 1983 Sonnenburg 1990 Hubertus von Sonnenburg, The Examination of Raphael’s Paintings in Munich, in Shearman and Hall 1990, pp. 65–78 Spring 2004 Marika Spring, Perugino’s Painting Materials: Analysis and Context within Sixteenth-Century Easel Painting, in The Painting Technique of Pietro Vannucci called Il Perugino, eds. Brunetto Giovanni Brunetti, Claudio Seccaroni, and Antonio Sgamellotti, Florence 2004, pp. 21–28 Springer 1878 Anton Springer, Raffael und Michelangelo, Leipzig 1878 Staley 1904 Edgcumbe Staley, Raphael, London 1904 Stedman Sheard 1979 Wendy Stedman Sheard, Antique in the Renaissance, exhibition catalogue, Northampton (MS), Smith College Museum of Art 1979 Stoltz 2012 Barbara Stoltz, ‘Disegno versus Disegno Stampato: Printmaking Theory in Vasari’s Vite (1550–1568) in the Context of the Theory of Disegno and the Libro de’ Disegni’, Journal of Art Historiography 7 (2012) (http://arthistoriography.files.wordpress. com/2012/12/stoltz.pdf) Strachey 1900 Henry Strachey, Raphael, London 1900 151 Suida 1920 Wilhelm Suida, ‘Leonardo da Vinci und seine Schule in Mailand’, Monatshefte für Kunstwissenschaft 13 (1920), pp. 251–97 Takahatake 2010 Naoko Takahatake, ‘Review on VGO: Ugo da Carpi, l’opera incisa: Xilografie e chiaroscuri da Tiziano, Raffaello e Parmigianino’, Print Quarterly 27 (2010), pp. 317–21 Talvacchia 1999 Bette Talvacchia, Taking Positions: On the Erotic in Renaissance Culture, Princeton (NJ) 1999 Talvacchia 2005 Bette Talvacchia, Raphael’s Workshop and the Development of Managerial Style, in The Cambridge Companion to Raphael, ed. Marcia B. Hall, Cambridge 2005, pp. 167–85 Talvacchia 2007 Bette Talvacchia, Raphael, London 2007 Tátrai 1983 Vilmos Tátrai, Cinquecento Paintings of Central Italy, Budapest 1983 Tátrai 1991 Vilmos Tátrai, Museum of Fine Arts Budapest: Old Masters’ Gallery: A Summary Catalogue of Italian, French, Spanish and Greek Paintings, eds. Ildikó Ember and Imre Takács, London and Budapest, 1991 Térey 1906 Gábor Térey, A Szépművészeti Múzeum Régi Képtárának leíró lajstroma, Budapest 1906 Térey 1916 Gabriel von Térey, Die Gemäldegalerie des Museums für Bildende Künste in Budapest: Vollständiger beschreibender Katalog I. Abteilung: Byzantinische, Italienische, Spanische, Portugisische und Französische Meister, Berlin 1916 Térey 1918 Gábor Térey, Az Országos Magyar Szépművészeti Múzeum Régi Képtárának katalógusa, 4th ed., Budapest 1918 Térey 1924 Gabriel Térey, Catalogue of the Paintings by Old Masters, Budapest 1924 Teza and Santanicchia 2004 Pietro Vannucci il Peruginio, eds. Laura Teza and Mirko Santanicchia, (Atti del Convegno Internazionale di studio 25–28 ottobre 2000), Perugia 2004 Thoenes 1986 Christof Thoenes, Galatea: Tentativi di avvicinamento, in Rome 1986, pp. 59–73 Thomas 1995 Anabel Thomas, The Painter’s Practice in Renaissance Tuscany, Cambridge 1995 Tietze-Conrat 1953 Erika Tietze-Conrat, ‘A Sheet of Raphael Drawings for the Judgement of Paris’, The Art Bulletin 35 (1953), pp. 300–2 Tolnay 1943 Charles de Tolnay, History and Technique of Old Master Drawings: A Handbook, New York 1943 Tömöry 1929 Edith Tömöry, ‘Az Esterházy Madonna előkészítő vázlatának egy másolata’, Archaeológiai Értesítő 43 (1929), pp. 272–73 Tschudi and Pulszky 1883 Hugo von Tschudi and Károly Pulszky: LandesGemälde-Galerie in Budapest vormals Esterházy– Galerie. Italienische und spanische Meister, Deutsche, niederländische und französische Meister, Vienna 1883 Turner 1961 Richard Turner, ‘Two Landscapes in Renaissance Rome’, The Art Bulletin 43 (1961), pp. 275–87 Turner 1966 Richard Turner, The Vision of Landscape in Renaissance Italy, Princeton 1966 Ullmann 1983 Ernst Ullmann, Raffaello, Leipzig 1983 Urbino 1983 Urbino e le Marche prima e dopo Raffaello, eds. Maria Grazia Ciardi Dupré Dal Poggetto and Paolo Dal Poggetto, exhibition catalogue, Urbino, Palazzo Ducale 1983 Urbino 2009 Raffaello e Urbino: La formazione giovanile e i rapporti con la città natale, ed. Lorenza Mochi Onori, exhibition catalogue, Urbino, Galleria Nazionale delle Marche 2009 Valazzi 2009 Maria Rosaria Valazzi, Riflessioni sulla bottega di Giovanni Santi e la migrazione dei modelli, in Urbino 2009, pp. 52–59 Van Dyke 1914 John Charles Van Dyke, Vienna, Budapest: Critical Notes on the Imperial Gallery and Budapest Museum, New York 1914 Van Tuyll van Serooskerken 2000 Carel van Tuyll van Serooskerken, The Italian Drawings of the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries in the Teyler Museum, Haarlem 2000 Varese 1994 Ranieri Varese, Giovanni Santi, Fiesole 1994 Varese 1999 Ranieri Varese (ed.), Giovanni Santi, (Atti del convegno internazionale di studi, Urbino, Convento di Santa Chiara, 17, 18, 19 marzo 1995), Milan 1999 Varese 2004 Ranieri Varese, Giovanni Santi e Pietro Perugino, in Teza and Santanicchia 2004, pp. 183–98 Vasari (trans. De Vere) Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects, translated by Gaston du C. de Vere, 2 vols., New York 1996 Vasari (ed. Milanesi) Giorgio Vasari, Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architetti [Firenze 1568], ed. Gaetano Milanesi, 9 vols., Florence 1878–85 Vatican 1984–85 Raffaello in Vaticano, ed. Fabricio Mancinelli, exhibition catalogue, Vatican, Monumenti, Musei e Gallerie Pontificie, 1984–85 Vatican 1999 Hochrenaissance im Vatikan: Kunst und Kultur im Rom der Päpste (1503–1534), exhibition catalogue, Vatican, Musei Vaticani and Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana 1999 Vayer 1957 Lajos Vayer, Meisterzeichnungen aus der Sammlung des Museums der Bildenden Künste in Budapest: (14.–18. Jahrhundert), Berlin 1957 Vecchi 1966 Pierluigi de Vecchi, L’opera completa di Raffaello, Milan 1966 Venturi 1900 Adolfo Venturi, ‘I quadri di scuola italiana nella Galleria Nazionale di Budapest’, L’Arte 3 (1900), pp. 185–40 Venturi 1920 Adolfo Venturi, Raffaello, Rome 1920 Venturi 1926 Adolfo Venturi, Storia dell’ arte Italiana IX: La Pittura del Cinquecento, Milan 1926 Venturini 1992 Lisa Venturini, Modelli fortunati e produzione di serie, in Maestri e botteghe, eds. Mina Gregori, Antonio Paolucci, and Cristina Acidini Luchinat, Florence 1992, pp. 147–64 Viardot 1852 Louis Viardot, Les musées d’Allemagne: Guide et memento de l’artiste et du voyageur, Paris 1852 Vienna 1835 Catalog der Gemälde-Gallerie Seiner Durchlaucht des Fürsten Paul Esterhazy von Galantha in Wien (Vorstadt Mariahilf Nr. 40)/Catalogue de la Galerie des Tableaux de Son Altesse le Prince Paul Esterhazy de Galantha à Vienne (Fauxbourg Mariahilf No. 40), Vienna 1835 Vienna 1844 Catalogue de la Galerie des Tableaux de Son Altesse le Prince Paul Esterházy de Galantha à Vienne/Catalog der Gemälde-Gallerie Seiner Durchlaucht des Fürsten Paul Eszterházy von Galantha in Wien, Vienna 1844 Wagner 1999 Christoph Wagner, Farbe und Metapher: Die Entstehung einer neuzeitlichen Bildmetaphorik in der vorrömischen Malerei Raphaels, Berlin 1999 Walsh 2000 Judith Walsh, ‘The Use of Paper Splitting in Old Master Print Restorations’, Print Quarterly 17 (2000), pp. 383–90 Washington, Chicago, and Los Angeles 1985 Leonardo to Van Gogh: Master Drawings from Budapest, ed. Teréz Gerszi, exhibition catalogue, Washington (DC) National Gallery of Art, Chicago, The Art Institute, and Los Angeles, Los Angeles County Museum of Art 1985 Wetering 1991 Ernst van de Wetering, ‘Verdwenen tekeningen en het gebruik van afwisbare tekenplankjes en ’tafeletten’, Oud Holland 105 (1991), pp. 210–27 Whitaker 1998 Lucy Whitaker, Maso Finiguerra and Early Florentine Printmaking, in Drawing 1400–1600: Invention and Innovation, ed. Stuart Currie, Aldershot 1998, pp. 45–71 Whitaker 2012 Lucy Whitaker, The Repetition of Motifs in the Work of Maso Finiguerra, Antonio Pollaiuolo and their Collaborators, in From Pattern to Nature in Italian Renaissance Drawings: Pisanello to Leonardo, eds. Michael W. Kwakkelstein and Lorenza Melli, Florence 2012, pp. 153–73 White and Shearman 1958 John White and John Shearman, ‘Raphael’s Tapestries and Their Cartoons’, The Art Bulletin 40 (1958), pp. 193–221 and 299–323 Wickhoff 1884 Franz Wickhoff, ‘Über einige Zeichnungen des Pinturicchio’, Zeitschrift für Bildende Kunst 1884 Winner 1998 Matthias Winner (ed.), Il Cortile delle Statue: Der Statuenhof des Belvedere im Vatikan (Akten des internationalen Kongresses zu Ehren von Richard Krautheimer, Rom, 21.–23. Oktober 1992), Mainz 1998 Witcombe 2004 Christopher L. C. E. Witcombe, Copyright in the Renaissance: Prints and the Privilegio in SixteenthCentury Venice and Rome, Leiden 2004 Witcombe 2008 Christopher L. C. E. Witcombe, Print Publishing in Sixteenth-Century Rome: Growth and Expansion, Rivalry and Murder, London and Turnhout 2008 Wittkower 1963 Rudolf Witkower, ‘The Young Raphael’, Allen Memorial Art Museum Bulletin 20 (1963), pp. 150–68 Wolk-Simon 2006 Linda Wolk-Simon, Raphael at the Metropolitan: The Colonna Altarpiece, New York and New Haven 2006 Wollanka 1906 József Wollanka, Raffael, Budapest 1906 Wright 2005 Alison Wright, The Pollaiuolo Brothers: The Arts of Florence and Rome, New Haven and London 2005 Zani 1819–24 Pietro Zani, Enciclopedia metodica critico-ragionata delle belle arti, Parma 1819–24 Zentai 1970 Loránd Zentai, Raffaello emlékkiállítás, exhibition and check-list, Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts 1970 Zentai 1978 Loránd Zentai, ‘Considerations on Raphael’s Compositions of the Coronation of the Virgin’, Acta historiae artium Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae (24) 1978, pp. 195-99 Zentai 1979 Loránd Zentai, ‘Contribution à la période ombrienne de Raphaël’, Bulletin du Musée Hongrois de Beaux-Arts 53 (1979), pp. 69–79 Zentai 1991 Loránd Zentai, ‘Le Massacre des Innocents: Remarques sur les compositions des Raphaël et de Raimondi’, Bulletin du Musée Hongrois des BeauxArts 74 (1991), pp. 27–41 Zentai 1998 Loránd Zentai, Sixteenth-Century Central Italian Drawings: An Exhibition from the Museum’s Collection, exhibition catalogue, Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts 1998 Zerner 1966 Henri Zerner, ‘Sixteenth-Century Italian Engravings in Vienna’, The Burlington Magazine 108 (1966), pp. 219–20 Zerner 1969 Henri Zerner, The School of Fontainebleau: Etchings and Engravings, New York 1969 Zerner 1972 Henri Zerner, Sur Giovanni Jacopo Caraglio, in Evolution générale et développements régionaux en histoire de l’art, Budapest 1972, pp. 691–95 Zug 2010–11 LINEA: Vom Umriss zur Aktion: Die Kunst der Linie zwischen Antike und Gegenwart, ed. Matthias Haldemann, exhibition catalogue, Zug, Kunsthaus 2010–11